Job:03171 Title:Typography Referenced (Rockport)

Page: 36

030-051 03171.indd 36 9/22/11 11:51 AM

36

Typography, Referenced

Text

Job:03171 Title:Typography Referenced (Rockport)

Page: 36

T

ype design involves abstraction. A type designer

imagines an idealized shape captured with

type-making technology, then typeset and rendered

on material or screen. Part of a type designer’s skill

includes capitalizing on the potential of these technologies,

while at the same time understanding their limitations

and their eff ect on the fi nal forms. Producing the same

typeface for diff erent sizes and for a range of technologies

is impossible without separating the reference model for a

typeface, often designed fi rst with pencil and paper, and each

implementation with its specifi c properties (usually relating

to rendering limitations, character set restrictions, etc.).

Technologies for which the type designer works directly on

the fi nal rendering size (foundry type, hot-metal type, some

photo typefaces, and Bitmap typefaces, etc.) have a direct

connection between the designer’s specifi cation and the

outcome. Even there, however, the technology imposes a degree

of abstraction. Early foundry type often has pen-like strokes,

yet punchcutters would often employ counterpunches to form

consistent negative spaces, carving separately the outside of

TYPE DESIGN AND DEVELOPMENT

Tools and Concepts

Typeforms are inextricably linked to writing. Not calligraphy, the craft of exploring expression with hand-

rendered forms, but writing in the widest possible sense, from graffi ti to a hasty “back in fi ve minutes” sign

to the most elaborate piece of public lettering. These forms determine the fundamental relationships between

strokes and empty space at the heart of typeface design. On top of these, the designer adds a layer of interpretation

and elaboration, making unknown combinations of typeforms with consistent texture and adding stylistic

cues. Even the most constructed of typefaces hints at the underlying rhythm of manual mark-making.

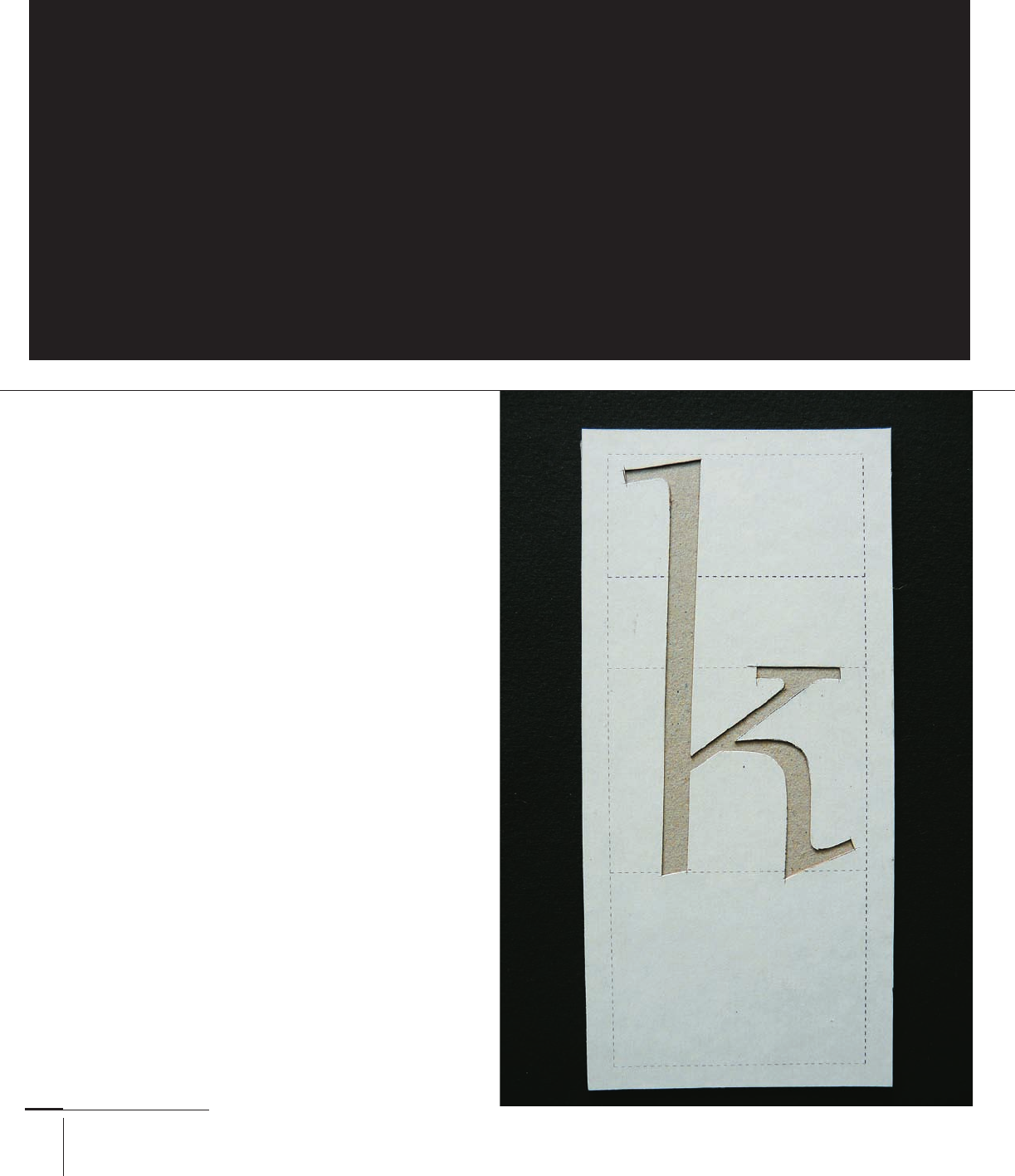

A card template cut by Jim Rimmer for his

typeface Stern. The gentle tapering of the

downstroke survived Rimmer’s use of a panto-

graph to reduce the shape onto a brass matrix.

Though Rimmer sketched the outline in pencil

before cutting the shape, the result echoes

a single stroke with a pen that modulates

width through rotation or pressure.

030-051 03171.indd 36 9/22/11 11:51 AM

Job:03171 Title:Typography Referenced (Rockport)

Page: 37

030-051 03171 C2.indd 37 10/12/11 9:14 AM

37

Type Design and Development

Text

Job:03171 Title:Typography Referenced (Rockport)

Page: 37

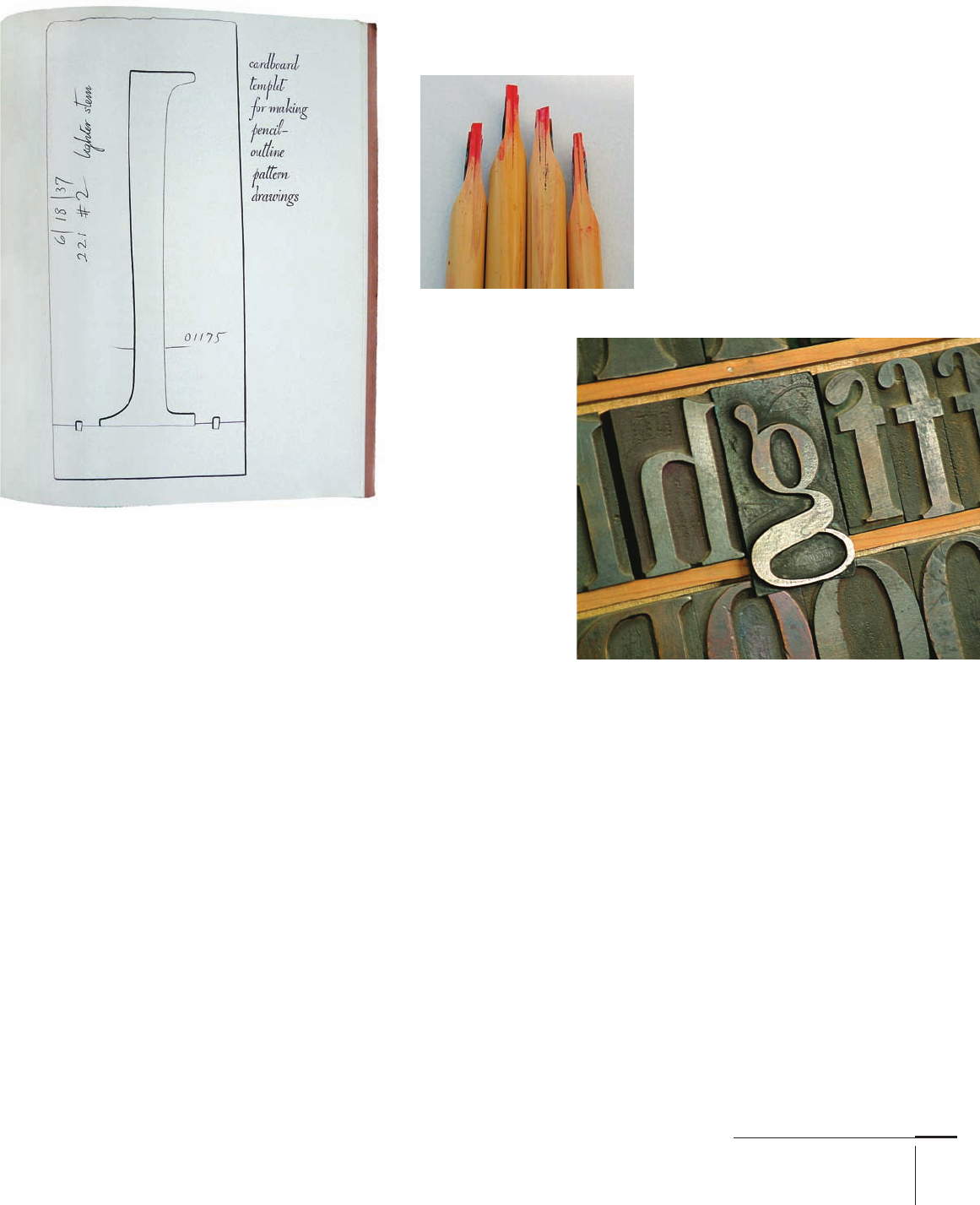

This series of nibs cut by Tim Holloway

appear in the angle required for Indian

penmanship, in which the stroke modula-

tion is the reverse of that for Latin. These

nibs were used to produce sketches that

formed the basis for a Devanagari typeface

from a major typeface foundry. The roots of

all scripts are infl uenced by the interface of

the writing tool, the pen-holding technique,

and the writing surface. Although smooth

paper is now ubiquitous, the charac-

teristics of palm leaves and other such

substrates still echo in typographic forms.

This sketch of a template cut in card by

William Addison Dwiggins in his 1940 monograph

WAD to RR showed a technique that allowed

Dwiggins to combine the fl uency of hand-rendered

curves with the facility to repeat the shape

in letters with similar strokes. The process

suggests an element of modularization,

but one reserved for main strokes only.

Wood letters, like other

carved or dug-out forms,

are largely agnostic as to

the style of letters on their

face. The letter-maker is

imagining a shape written,

designed, or constructed,

and transfers this onto

the face of the block. The

stylistic cues survive

longer than the original

tools and techniques for

letter making, perpetu-

ated through the longevity

of the format and the

demand for the style.

the stroke. Hot-metal type making operations would

use brass patterns, specially made French curves, and

other methods of storing shapes. Throughout the hot-

metal and phototypesetting eras, shapes were captured

as engineering drawings, each letter several inches

high, at scales that had little to do with the specifi c tool’s

movements. The arrival of platform-independent digital

type stored without reference to the rendering size pushed

further this separation between the model for a typeface

and the specifi c shape of its rendered forms.

When designing a script typeface, the designer can

reference written forms directly, modifying for output

size and rendering. Most typefaces, however, depart

from written form shapes. To ensure a typeface’s consis-

tency, the designer must develop a mental model of a tool.

This may imitate the behavior of a writing tool, but may

include mark-making and movement quite unlike any-

thing possible to render with a real tool. An invented tool

that, for example, makes incised vertical strokes and pen-

like bowls can become the basis for a wide range of styles,

ensuring consistency without the limitations of a spe-

cifi c tool. This approach is especially pertinent in scales

for which the limits of manual tools do not off er useful

guidelines, such as typefaces in very small sizes. In those

extremes a tool model might mark the counters and space

between elements as much as the strokes.

It also does not hinder the generation of large, con-

sistent families even without directly related elements.

A light condensed, for example, can belong to the same

family as a wide extra bold when the modulation, the

joins between vertical strokes and curves, and the shape

of instrokes and outstrokes are similar. Imagined tools are

particularly helpful when a design abandons the organic

shapes that reference pens, nibs, brushes, and other exist-

ing tools for entirely constructed shapes, treatments of the

strokes that hint at perspective, or surface eff ects.

030-051 03171.indd 37 9/22/11 11:51 AM

Job:03171 Title:Typography Referenced (Rockport)

Page: 38

030-051 03171.indd 38 9/22/11 11:52 AM

38

Typography, Referenced

Text

Job:03171 Title:Typography Referenced (Rockport)

Page: 38

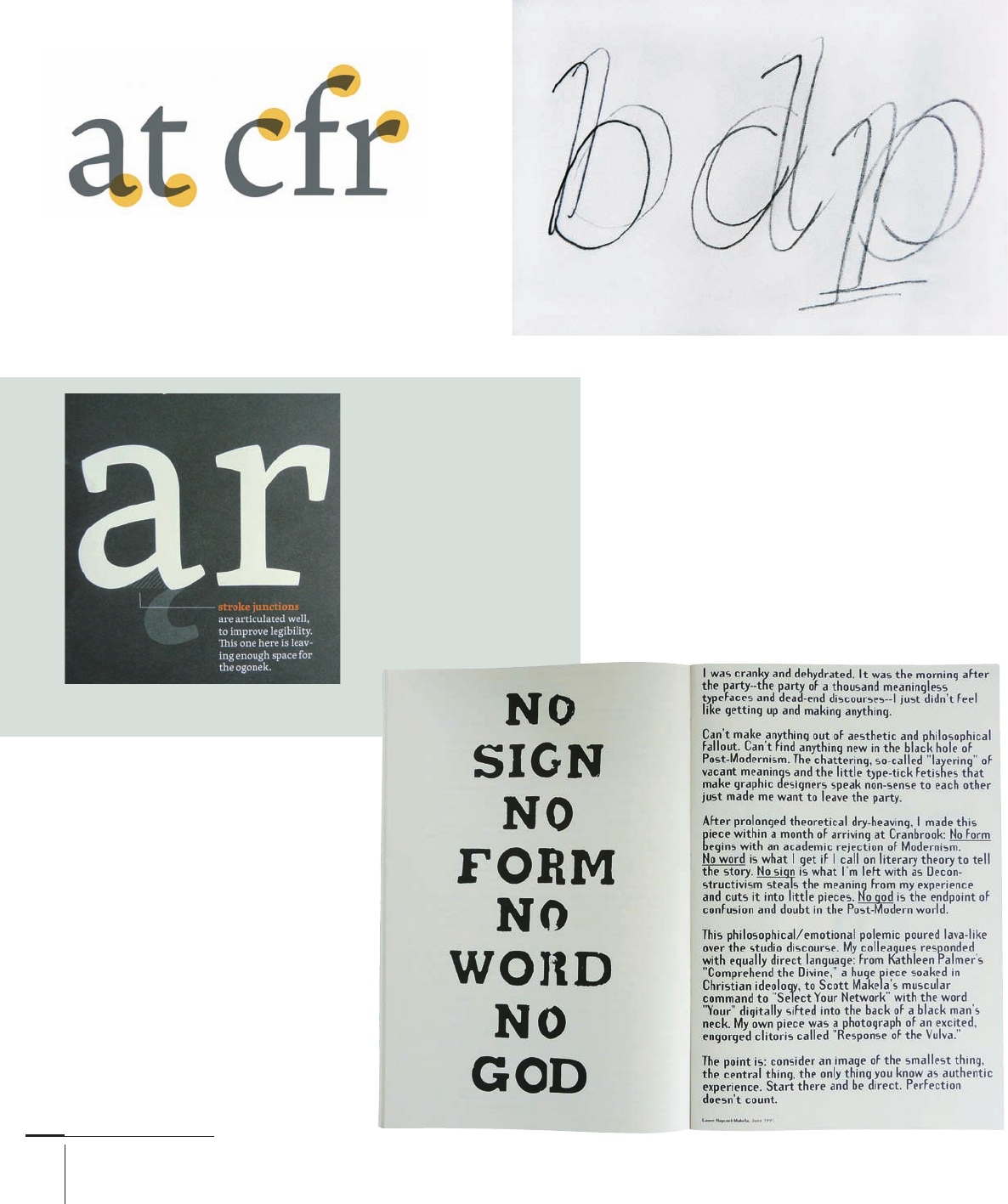

This spread from Emigre , designed by

Laurie Haycock Makela, exemplifi es the

sea change in type making and typeset-

ting brought by platform-independent font

formats and object-based layout. Although

seen initially as a place for experimenta-

tion and new thinking on design, Emigre

also functioned as a mirror to precon-

ceptions. Barry Deck’s Template Gothic

is typical of an approach questioning

the means of type making with roots

all the way back to Wim Crouwel’s

proposal for a new style of typefaces.

This detail from a poster by Type-

Together on David Březina’s Skolar

shows a typical hybrid typeface.

The bowl of the a and the bottom

serifs have organic modula-

tion, but the top serifs are typical

of constructed elements. Some

of the details get lost in smaller

sizes and lower resolutions such as

footnote text, but the overall low

contrast helps maintain texture.

To understand the conventions for weight

distribution and modularization, hold two

pencils tied together and write slowly with

the pencil angle unchanged. The resulting

shapes will have, for the Latin script mainly,

the stress and modulation typical of the

traditional western style. Abstracted from

the specifi c “nib” dimensions, this method

can help answer questions such as where to

place the thick strokes in extreme widths.

In Eben Sorkin’s Arrotino, the baseline outstrokes of

the a and e are similar but not identical. The same

treatment in the top outstrokes of the c, f, and r ensures

a consistent typeface that retains a hint of written

irregularity and balanced terminals. This is partic-

ularly noticeable in the r, which has a shorter arm,

placing the terminal close to the strong top half-serif.

030-051 03171.indd 38 9/22/11 11:52 AM

Job:03171 Title:Typography Referenced (Rockport)

Page: 39

030-051 03171.indd 39 9/22/11 11:52 AM

39

Type Design and Development

Text

Job:03171 Title:Typography Referenced (Rockport)

Page: 39

TYPE DESIGN AND DEVELOPMENT

From a Letter to a Typeface

It is not too diffi cult to design one letter or even a few. But to design a full alphabet, a designer

must balance complementary and contrasting features across a large character set. Making sure

that range of shapes combines to form a unifi ed whole is the fi rst step toward a new typeface.

This underlying homogeneity distinguishes typefaces from lettering and allows integration of

unique features that impart personality and style while maintaining readability (330).

W

here to start? Many designers think of some

variation of “hamburgefons” (a typical

test word used by type foundries) when

starting a new typeface. But which of those

letters to attempt fi rst? Ideally, a designer works with a

small set of letters that allows for the rapid development

of ideas while embodying a wide range of strokes to give

an impression of the face’s more distinctive features.

The details here depend on a number of factors, not least

of which is the designer’s experience and skill and whether he

or she is making an entirely original design or one inspired

by an existing typeface. Sketching the n and the o alone is not

enough to give a good idea of where the typeface will end up.

Sequences such as a f g n p r s t, a b d e g h i n o y, and a g h m n o

p are well documented as starting sequences; they allow rapid

development of a new typeface. An experienced designer might

start with only a e h n t, or even b a n d.

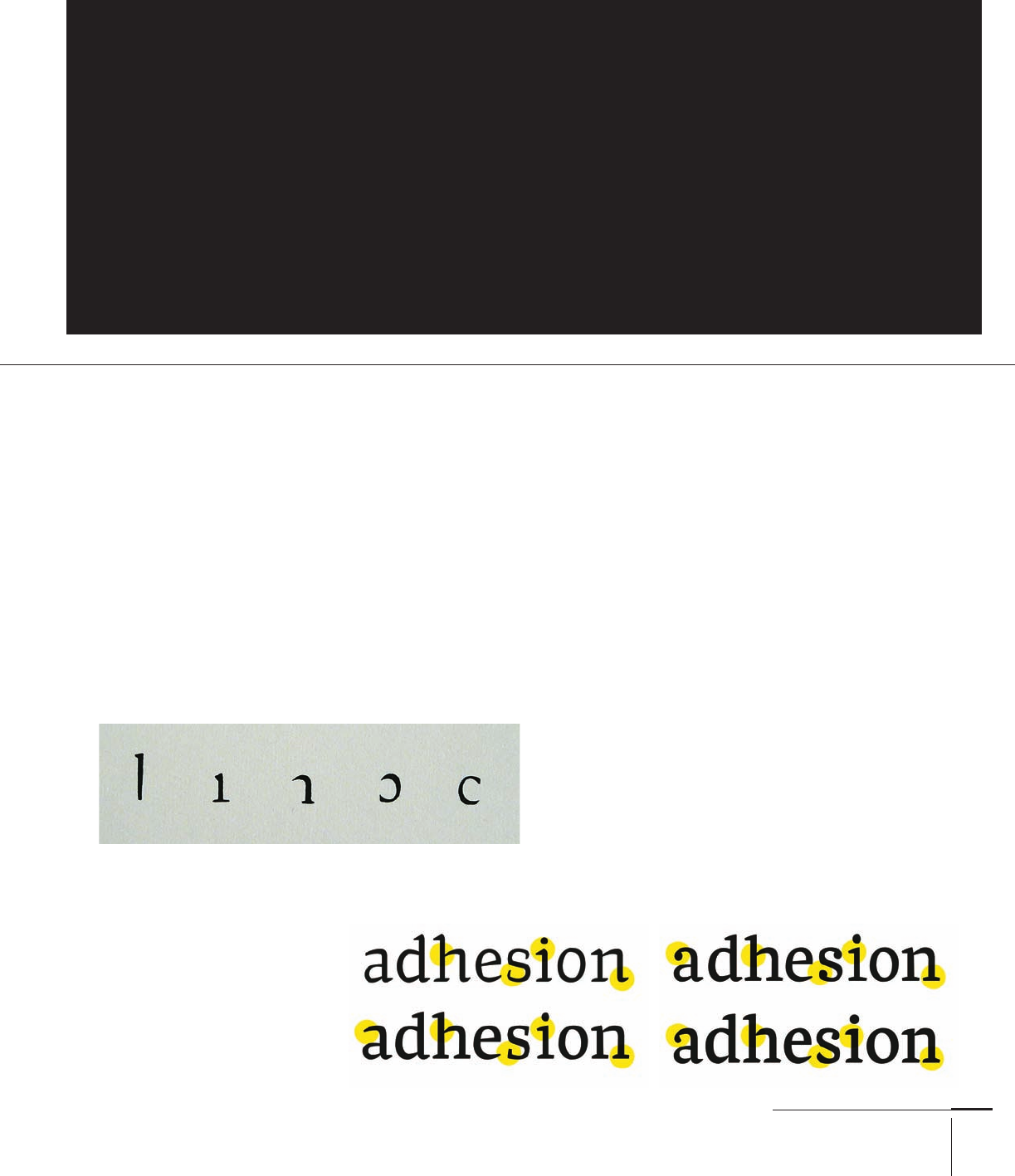

A new designer might try the letters a d e h i n o s (or the word

“adhesion” for ease) to get started. The letters off er a good com-

promise: It’s a small enough set for the designer to change

direction quickly, but it’s large enough to off er a good balance

of typeface-wide features and style in text settings. Letters

such as f g k, which are relatively unique, are omitted, as are

the diagonals (k v w x y z), which share strong features among

themselves, but not with the other letters.

These are four stages in the early develop-

ment of Neel Kshetrimayum’s Frijky. The

fi rst drawings show main strokes that are

too light, leading to light gray paragraphs.

In the next few versions the strokes

gain weight and the curves become less

pointed. The highlighted terminals start

as inconsistent outstrokes, but soon

change to relatively safe slab serif shapes.

The terminals of the fourth version

balance a range of shapes with enough

presence to emphasize the baseline.

Here is a sequence of basic strokes identifi ed by Dwiggins for his

typeface Falcon: long and short downstrokes, a top joining stroke, and

clockwise and counter-clockwise bowls. From these fi ve basic strokes,

the designer can easily develop twelve to fi fteen letters depending on

the design’s homogeneity. The remaining letters either have diagonal

strokes or unique features that allow the designer to refi ne the style.

030-051 03171.indd 39 9/22/11 11:52 AM

Job:03171 Title:Typography Referenced (Rockport)

Page: 40

030-051 03171.indd 40 9/22/11 4:27 PM

40

Typography, Referenced

Text

Job:03171 Title:Typography Referenced (Rockport)

Page: 40

TYPE DESIGN AND DEVELOPMENT

Design by Team

There has been a gradual return to typeface design as a team enterprise, drawing on the expertise of a group

rather than an individual. This concept is not new: Typeface design in the hot-metal and phototype eras

was very much a team product. But just as the digital, platform-independent formats enabled designers

to function outside of a heavy engineering world as sole traders, so it enabled the explosion of character

sets and families to unprecedented levels. The necessary skills and the sheer volume of work required for

text and branding typefaces have driven a growth of mid-size foundries where people with complementary

skills collaborate on a single product. The corollary is a rise in the need for documentation and explana-

tion to a community of fellows. The short-lived “creative hermit” model is giving way to new work modes.

M

ost of the typeface drawings that museums,

archives, and collections have show x-heights

at anything from a couple inches (or centi-

meters) to around ten inches (25 cm) high,

depending on their ultimate purpose. Designing on a com-

puter screen requires a similarly large zoom factor. In display

typefaces (213), this often refl ects the rendering scale to

allow the designer to grasp how the typeforms will look. But

typefaces rendered at text sizes demand that the designer

understands how design decisions translate across scales.

This is one of the trickiest challenges for new designers.

Understanding how to make shapes at one scale behave

a particular way in another scale is not straightforward.

Readers look at words, lines, or paragraphs of typeset text,

but a designer makes changes only to a single character.

Imagining how a small change in a single letter will aff ect

a whole paragraph is not an innate skill, but rather one

learned through experience.

Most designers use interpolation, for example, the Multiple

Master tools built in the widely used font-design application

Fontlab, to develop and fi ne-tune designs. This works for any-

thing from fairly basic proportions to fi ne details. Although

interpolation can be a powerful tool, its eff ectiveness depends

on the quality of the fonts at the extremes and the span the

interpolation covers for each parameter. (For example, it is

easier to obtain good results if interpolating within a relatively

narrow range, rather than between extreme weights or widths.)

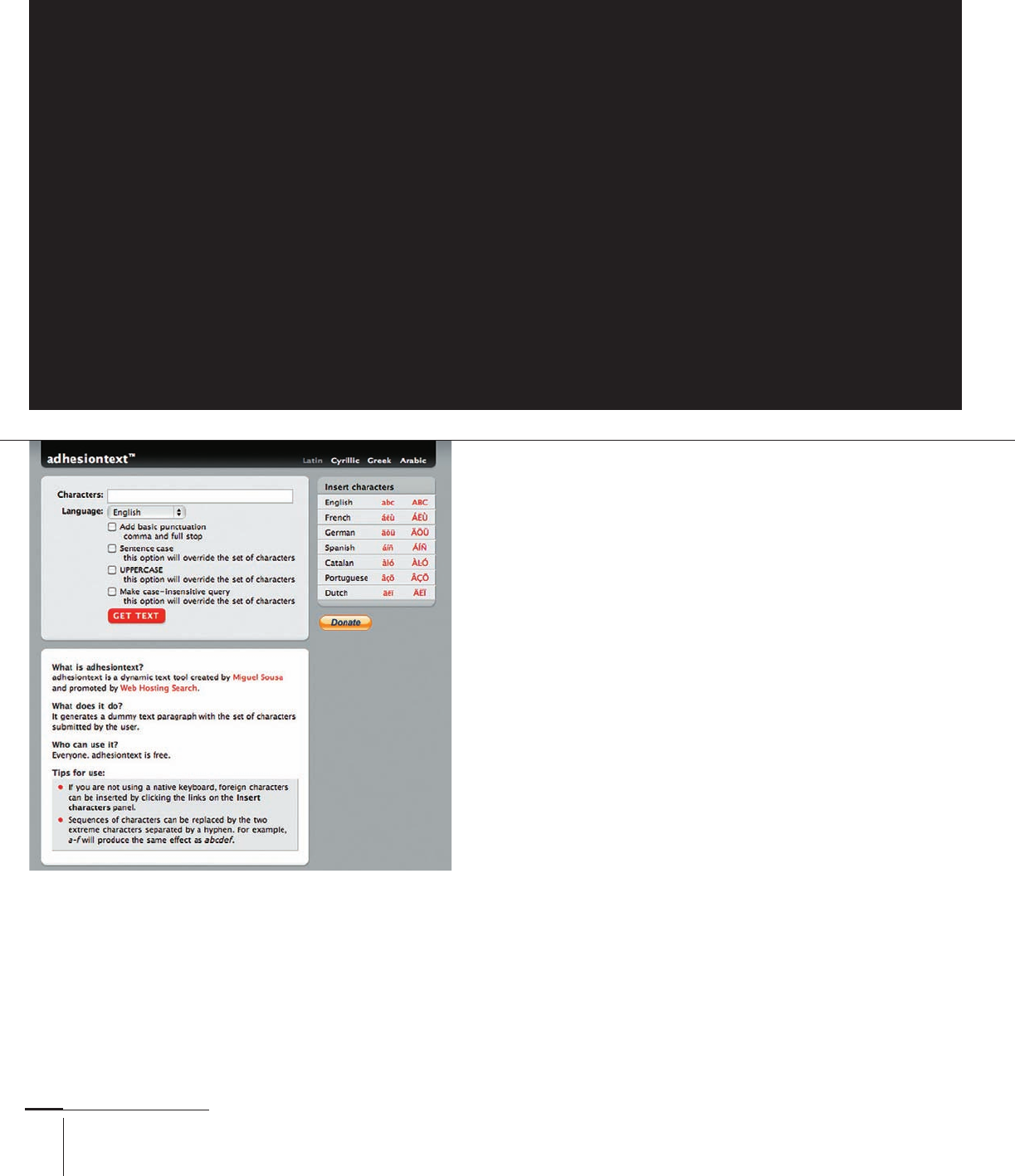

Miguel Sousa’s text generator grew out of the need to

source test texts for incomplete character sets. The tool

allows designers to test the feel of their typeface as it

develops across many languages, with texts that imitate

real context as closely as possible. Adhesiontext.com is

one of a growing range of online typeface design tools.

030-051 03171.indd 40 9/22/11 4:27 PM

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.