Job:03171 Title:Typography Referenced (Rockport)

Page: 41

030-051 03171.indd 41 9/22/11 11:52 AM

41

Type Design and Development

Text

Job:03171 Title:Typography Referenced (Rockport)

Page: 41

Another use of interpolation

involves the development of grades,

which allow the designer to fi ne-tune

the fi t of a typeface to specifi c presses.

Here the widths of the diff erent styles

remain identical to avoid the need to

refl ow text based on grade selection.

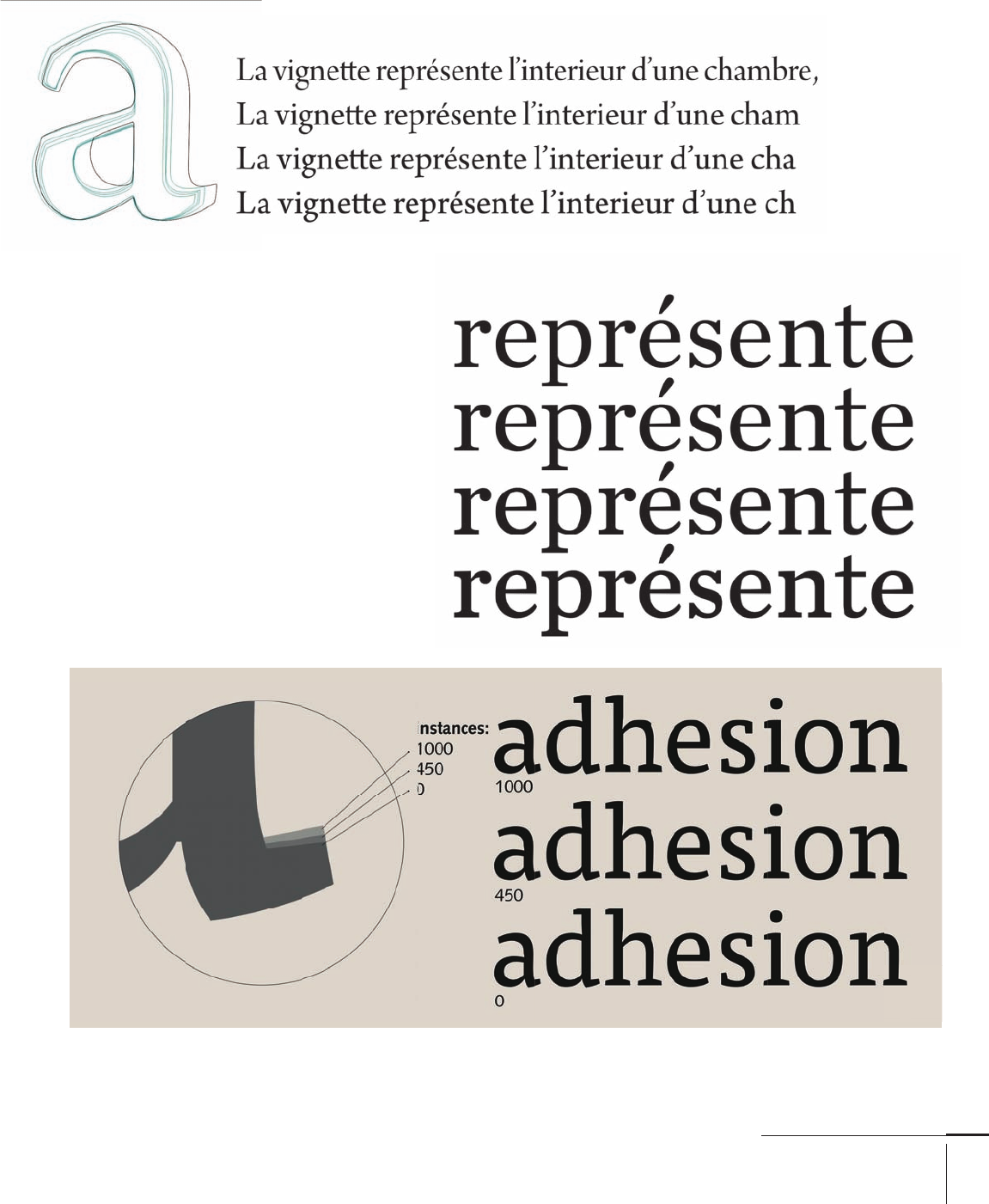

Typeface designers may use interpolation to produce

closely matched versions of typefaces optimized for

specifi c purposes, such as Adobe’s Arno Pro, which ships

with fi ve optical sizes (small text [for captions], regular,

subhead, and display). Four of these appear here as

green outlines; for comparison, the black outline is the

bold. Once the basic interpolation is done, the designer

often returns to the outlines to improve details for inter-

mediate styles. Setting the four variants at the same

size highlights the weight and spacing diff erences.

Trials during the development of Mitja Miklavčič’s Tisa show that the two

extremes share basic dimensions. Just the weight of the outstrokes changes.

The same approach was used to fi ne-tune many aspects of the typeface.

030-051 03171.indd 41 9/22/11 11:52 AM

Job:03171 Title:Typography Referenced (Rockport)

Page: 42

030-051 03171.indd 42 9/22/11 11:52 AM

42

Typography, Referenced

Text

Job:03171 Title:Typography Referenced (Rockport)

Page: 42

T

he rendering environment (the test design appli-

cation’s display of type) plays an important role in

the connection between the appearance of para-

graphs and specifi c design choices. Type design

applications may allow the designer to zoom in until a detail

fi lls the whole screen, but this precludes the display of a

whole paragraph. Zoom out to allow multiple lines of text

on the screen, and the low resolution renders the details

too fuzzy to judge. But printouts are also unreliable: Post-

script version, toner level, paper quality and orientation, and

many other factors infl uence the quality of laser output.

Instead, get printouts from diff erent printers. Some type

designers sneak lines of type on the margins of print jobs (or

even place small advertisements in their own typeface) to get an

idea of how the typeface performs in off set conditions. Here’s

a tip: Process black is generally lighter than laser toner, and a

typeface may look washed out on off set.

For many years, a limit of 256 characters per font hampered

digital typefaces, as did a need to ship in linked styles of four:

regular, italic, bold, and bold italic. Most foundries have now

expanded their character sets to include coverage for Latin

script and are extending into other scripts, driven mostly by

branding demand. But the most interesting developments are in

regard to thinking about typeface families.

The establishment of OpenType and the support of wide fam-

ilies by page-layout applications allowed designers to rethink

what constitutes a family. Traditional, individually bought

typefaces were often developed to meet specifi c user needs. For

example, a family like Monotype’s Grotesque had several widths

and weights for the upright styles, but only two inclined ones.

The diff erent styles have strong diff erences, and some weights

seem reworked from standalone typefaces, but the family

hangs together well because the individual styles work for their

intended purpose. Although the completeness of a Univers-like

() system is appealing, it irons out a designer’s interpretation

of a style for small sizes, display weights, and even alternate

styles within the text styles.

At the same time, a family based on small weight increments

can help publications such as magazines that need to combine

diff erent typefaces for headings, straplines, main text, captions,

pull quotes, etc. The ability to select something a little heavier

or lighter can make the diff erence between using a typeface or

not. The profusion of typeface families with many weights near

the middle of the range (regular, book, medium, semi-bold, etc.)

is a welcome development in the past decade.

TYPE DESIGN AND DEVELOPMENT

Rendering Environment

Three letters from -point Minion Pro, printed on a dpi laser printer, photographed under a

microscope. In comparison with the original outlines (left) the laser printer introduced inconsisten-

cies of width in the vertical strokes, as well as in serifs and terminals. Although the resolution of laser

printers is generally higher, this level of detail is comparable to many print-on-demand services.

030-051 03171.indd 42 9/22/11 11:52 AM

Job:03171 Title:Typography Referenced (Rockport)

Page: 43

030-051 03171.indd 43 9/22/11 11:52 AM

43

Type Design and Development

Text

Job:03171 Title:Typography Referenced (Rockport)

Page: 43

Testing the Design

The process of typeface design is, in

essence, a reductive refi nement of

details. First ideas are just sketches

that off er starting points followed by

a clear methodology of structured

changes, reviews, testing—and rep-

etition of the whole process. The

designer’s attention progresses in

ever-decreasing scales of focus:

• First, paragraph-level values

on the overall density of a design

• Next, fundamental interplay

of space and main strokes

• Third, elements within

a typeface that ensure

consistency and homogeneity

• Finally, elements that impart

individuality and character

At the heart of this process is a

question-fi lled dialogue: What are

the conditions of use for the new

design? How will the success of the

design be evaluated?

The wider the typeface family, the

deeper the need to test conclusively,

not only with documents that high-

light the typeface’s qualities, but

also with documents that approxi-

mate a wide range of possible uses.

Even very tight briefs (as in the case

of typefaces for corporate clients)

can generate an extremely broad

range of uses—scenarios that may

even change after typeface delivery.

But good designers also under-

stand the constraints of their

testing environment. Ironically,

the screen is gradually becoming

an area of better control than print.

Standardized tests to check the

quality of type rendering on screen

are increasingly published online

for developers and designers to use.

But the limitations of laser printers,

the range of quality in digital print-

ers, and the loss of wet proofs for

off set complicate testing.

Monotype Grotesque, a reference

historical sans family with an

incomplete family, works well

for a wide range of documents.

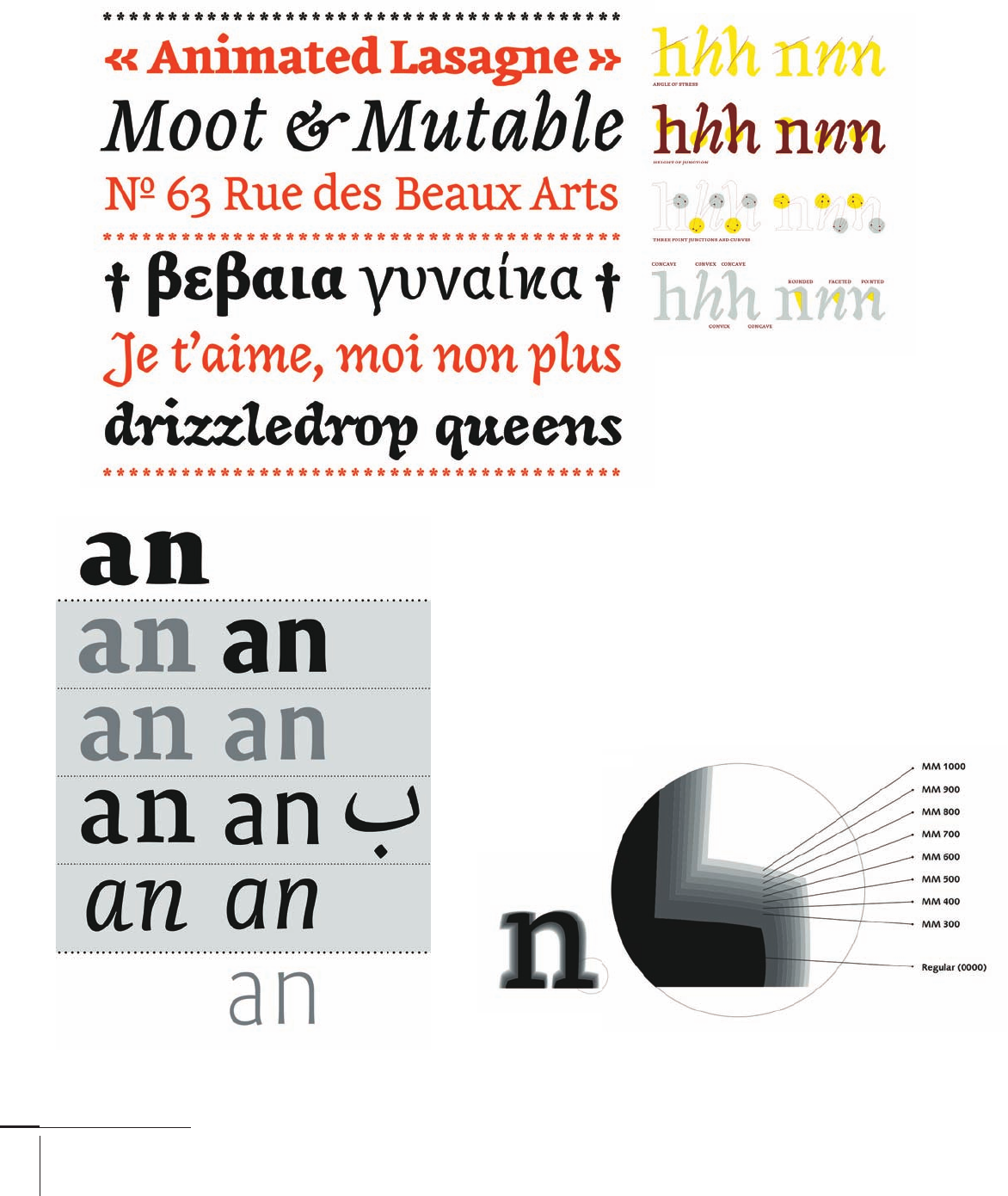

Emilie Rigaud’s Coline

combines a relatively

restrained regular

and bold, with an

informal upright style,

an upright italic with

an associated light

version, and an extra

bold that pushes the

style to its extreme.

030-051 03171.indd 43 9/22/11 11:52 AM

Job:03171 Title:Typography Referenced (Rockport)

Page: 44

030-051 03171.indd 44 9/22/11 11:52 AM

44

Typography, Referenced

Text

Job:03171 Title:Typography Referenced (Rockport)

Page: 44

Aoife Mooney’s Magnimo employs

both an upright italic and an

inclined one. There is a careful mix

of features across the three styles to

ensure that all combinations hang

together well. Depending on the text

to be set and the document’s tone,

the designer can choose a more

or less discreet secondary style or

employ all three instead of using

an extra weight for diff erentiation.

Mathieu Reguer’s plan for the

Cassius family demonstrates the

separation between text styles

and display weights: The text

variants are interpolated, but the

extra bold and light need to be

drawn separately to maximize

eff ect. Note also the beginning of

the extension into a second script,

starting at the main text weight.

A study of a typeface’s possible weight variants can be

extremely helpful for publications such as magazines

that need to combine diff erent typefaces for headings,

straplines, main text, captions, pull quotes, and so on.

030-051 03171.indd 44 9/22/11 11:52 AM

Job:03171 Title:Typography Referenced (Rockport)

Page: 45

030-051 03171.indd 45 9/22/11 11:52 AM

45

Type Design and Development

Text

Job:03171 Title:Typography Referenced (Rockport)

Page: 45

TYPE DESIGN AND DEVELOPMENT

Space Matters

Punchcutters and letter cutters know fi rsthand that the most important element in a typeface is the

space between letters. Readers are terrible at identifying specifi c widths along a line of text but extremely

adept at picking out inconsistencies. Within the space of a few words, a designer can establish the

typeface’s basic rhythm; with small variations of basic dimensions and spacing a typeface can appear

normal or impart the impression of a wider or narrower variant. This basic pattern greatly aff ects

readability (330) of the typeface, even more so than the details of the dark shapes themselves.

A detail from the Encyclopedie of shows composed foundry type. Even though

digital type is disembodied, the same basic measurements apply. Studying good quality

typesetting for hand-set type can help a designer discover how much is possible to

achieve with good spacing (before the application of kerning). The middle row italics

are off set on the body, an approach many digital typeface designers today use.

030-051 03171.indd 45 9/22/11 11:52 AM

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.