4. Chairman Greenspan Counts on Housing

For most Americans, owning a home is a deep-seated and long-standing desire. The quest for home ownership has arguably motivated households’ financial decision making since the nation’s founding. Yet why, in the middle of the century’s first decade, did so many of us decide to buy houses all at once? During the peak of the housing boom in 2005, an astounding proportion—more than one-tenth—of the nation’s homes were bought and sold.

Many factors drove this home-buying binge, but the biggest was easy credit—more specifically, the period’s record-low mortgage rates. In a normal year, more than three-fourths of all home sales require a mortgage loan, and, on average, about three-fourths of a home’s purchase price is paid for with borrowed money. The cost of borrowing money is critical for home sales; nothing else we buy as consumers depends so much on it.

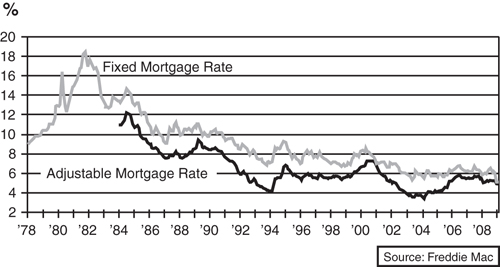

Houses seemed a once-in-a-lifetime buy at the start of this decade. A fixed-rate loan to a prime borrower carried an interest rate of slightly more than 5%; rates on adjustable mortgage loans were well below 4%. Fixed-rate loans had not been so cheap since just after World War II, and ARM rates had never been lower. These rates were even more enticing because, only a few years earlier, fixed-loan rates were above 8% and ARM rates more than 7%.

Behind the bargain-basement interest rates was a Federal Reserve on high alert. An unending string of calamities, beginning with the bursting of the Internet stock bubble and extending through 9/11 and the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, weighed heavily on the economy. Even the massive Bush tax cuts weren’t providing much of an economic boost. China’s rapid emergence on the global scene was also creating an economic upheaval. Thanks to China’s ultra-low-cost production, prices for manufactured goods were falling all around the world. The Fed’s overriding concern quickly became not inflation, but deflation—the kind of broad price decline that the United States hadn’t seen since the Great Depression.

Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan responded with an unprecedented reduction in interest rates. Greenspan had refused to use the powers of the Fed to prick the tech-stock bubble of the late 1990s, arguing that it wasn’t the central bank’s place to second-guess investors. But he believed the Fed had a duty to step in aggressively after bubbles burst if their fallout threatened the real, outside-of-Wall-Street economy. And if the economy was at risk of falling into a deflationary trap, the Fed had to ride to its rescue.

Greenspan believed that if interest rates were quickly brought low enough, they would ignite a surge in housing activity. He was correct; home sales, construction, and housing prices all took off. The housing boom had begun. As people noticed their neighbors’ house prices rising, they began to feel wealthier themselves. They also discovered that lenders were eager to help them take some of that wealth out of their homes, via refinancing, home equity loans, and other newly popular financial schemes. In effect, homes were being turned into cash machines, helping fuel a consumer buying binge.

Some saw danger in this; Greenspan did not. The Fed chairman believed that although stocks and other financial assets might be prone to bubbles, housing was immune. He argued that the costs involved in buying and selling homes were too high for speculation to take root. Moreover, even if some local housing markets became overheated, the danger to the wider economy was limited because housing was inherently a local market, not a national one.

Greenspan was partly correct; the housing boom lifted the economy out of its post–9/11 malaise. But he was dead wrong about the impact of a housing bubble. When it burst, it set off the subprime financial shock.

Lower Rates, Bigger Homes

Nothing matters more to a potential home buyer than the prevailing mortgage rate. This rate determines how large a home, if any, a household can afford. Other things matter, too—such as employment, credit history, and whether the buyer can come up with a down payment—but the principal hurdle between a household and a home is the mortgage rate.

During the past quarter-century, this hurdle has grown steadily smaller, and it all but disappeared in the housing boom. It was hard to even remember how high mortgage rates had once been. In the early 1980s, annual interest on a 30-year fixed mortgage exceeded 18%. A decade later, it had fallen to a more manageable 10%, and by 2000, it was even lower, at 8%. As recession and deflation fears took hold after 9/11 and during the invasion of Iraq, fixed rates briefly touched 5.25%. They moved higher during the decade but rarely stayed much higher than 6% for long (see Figure 4.1).

Figure 4.1 Steadily falling mortgage rates.

The decline in rates translated into much smaller monthly mortgage payments. The average home buyer in 2000 took out a $150,000 mortgage. At the 18% mortgage rates of two decades earlier, such a loan would have required a $2,400 monthly payment,1 half the average household’s after-tax income. At 8%, the payment is $1,250; at 6%, the cost drops to a very manageable $1,050 per month.

You can best see the difference between the housing market of the early 1980s compared to the market early this decade through the experience of a first-time home buyer. A first-timer 25 years ago couldn’t afford to purchase the home he grew up in—the home his parents had bought when they were about the same age. In contrast, a first-timer early in this decade, just before the housing boom, could not only buy the home he grew up in, but also afford to add a pool or another bedroom.

A Call to ARMs

A quarter-century of falling interest rates helped make housing much more affordable to more Americans. The rise of the adjustable-rate mortgage (ARM) further magnified this process. ARMs had been around since the late 1960s in a few California communities, but they went nationwide during the period of high and volatile interest rates in the early 1980s.2 Lenders liked ARMs not because they were cheaper for borrowers—although that was a plus for marketing—but because they reduced the lenders’ own interest-rate risk. Banks make a profit only when the rates they charge for loans exceed the rates they pay to depositors. When mortgage rates are fixed for 30 years, banks run a risk that deposit rates might rise in the interim and wipe out their earnings. This happened in the early 1990s; thousands of savings and loan institutions became insolvent as a result.3

Enter the adjustable-rate mortgage. Because ARM rates move periodically, lenders can more easily match ARM rates with the rates they pay depositors. The initial rate on an ARM is much lower than that on a fixed-rate loan, largely because the borrower is taking on the interest-rate risk the lender wants to avoid. If deposit rates rise—which they generally do if rates in money markets or for securities such as Treasury bills rise—borrowers’ ARM payments rise soon thereafter. But a borrower who is willing to take this risk can start out with a much cheaper mortgage. During the past quarter-century, ARM rates have averaged almost 2 percentage points below rates on fixed-rate loans. For a $200,000 loan—about the average size of a mortgage in 2008—this translates into a monthly saving of $275, a large difference for a household stretching its budget to buy a home.

Many homeowners who don’t plan to stay put for long also find ARM loans attractive. The average American moves at least once every seven years; for these people, the industry invented a hybrid version of the ARM in which the initial interest rate can remain fixed for up to seven years before adjusting. Such loans are less costly than fixed-rate mortgages because the ARMs are linked to short- and intermediate-term interest rates, which typically are lower than the long-term rates that govern fixed-interest mortgages.

Shifting interest-rate risk from lenders to borrowers was thought to be a win-win proposition: The chance of another S&L-style debacle would diminish, and home buyers would have new choices, potentially saving them money if they chose wisely. Even Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan was an avid fan of ARMs. In a speech to a credit union trade group in early 2004, Greenspan argued, “Recent research within the Federal Reserve suggests that many homeowners might have saved tens of thousands of dollars had they held adjustable-rate mortgages rather than fixed-rate mortgages during the past decade, though this would not have been the case, of course, had interest rates trended sharply upward.”4

Greenspan urged mortgage lenders to provide “greater mortgage product alternatives to the traditional fixed-rate mortgage. To the degree that households are driven by fears of payment shocks but are willing to manage their own interest rate risks, the traditional fixed-rate mortgage may be an expensive method of financing a home.”

Lenders responded to Greenspan’s “call to ARMs” aggressively, developing a new, wider array of adjustable loans. Originally, ARMs had been designed relatively simply, with rates that adjusted based on the one-year Treasury note or an S&L’s cost of funds—mostly short-term deposits.5 Perhaps it was just coincidence, but soon after Greenspan’s speech, lenders began aggressively marketing a plethora of ARM products, ranging from the hybrid ARM, to the option ARM, to the teaser-rate subprime ARM.

The steady decline in interest rates and smorgasbord of loan products provided a lift to housing that became magnified several times over during the housing boom. Most households hunting for a home begin by meeting with a real estate agent. Realtors are adept at quickly sizing up the prospective buyer’s financial circumstances. Based on those, the agent determines the lowest mortgage rate available and, therefore, just how much the buyer can spend on a house. Often the first home shown is priced just above what the agent has determined the buyer can afford. For all but the most disciplined buyers—and there weren’t many in the housing boom—you psychologically can’t go back. Buyers are primed to buy as much home as they can possibly afford.

Home sellers can sense this, of course, and as agents and buyers show up at the door more frequently, asking prices begin to rise. It doesn’t take long for lower mortgage rates to result in higher house prices. Rising prices don’t necessarily dissuade prospective buyers—at least, they didn’t during the housing boom—as buyers begin to factor future house-price gains into their decision making. The higher the expected future profit, the more willing a buyer will be to buy a bigger home and take on a bigger mortgage. Moreover, if the value of a home appreciates faster than the interest rate on its mortgage, then the bigger the mortgage, the bigger the gains for the homeowner.

Under such conditions, it makes sense to buy as much house as a lender will allow.6

Greenspan’s “Put”

Interest rates fell steadily through the 1980s and 1990s, but they plunged in the early 2000s to lows rarely experienced, igniting the housing boom and setting the stage for the subprime financial shock. Driving interest rates lower was the Greenspan-led Federal Reserve Board. Between New Year’s Day 2001 and Memorial Day 2003, the Fed engineered a dramatic decline in the benchmark lending rate for banks, taking it from 6.5% all the way to 1%. Not since John F. Kennedy was president had the Fed funds rate been so low.7

The Fed drove rates down as the collapse of Silicon Valley’s tech-stock bubble in early 2001 began to ripple through the economy far beyond California. Stock prices had surged nearly five-fold during the 1990s, and prices for the shares of technology companies—particularly those exploiting the amazing new Internet—had skyrocketed by some ten times, as measured on the NASDAQ exchange (see Figure 4.2). Speculation fueled this bubble; investors bought stock assuming that because their prices had been rising rapidly, they would continue to do so, using borrowed money—leverage—to multiply their bets. Margin debt—money borrowed from stockbrokers and used to purchase extra shares—piled up in record amounts.8

Figure 4.2 The technology stock bubble: NASDAQ Stock Index.

The bubble began to burst only days after stock prices hit their peak, in the weeks just after the turn of the decade. By the end of 2000, investors were completely panicked. The value of the NASDAQ was slashed in half. Other, broader measures of stock prices held up better, at least for a while, but more than $2 trillion in household stock wealth eventually disappeared. The economic fallout was substantial. By Christmas 2000, consumer confidence was plunging, hiring had come to a standstill, and businesses were cutting back on investment spending, even for new high-tech equipment. The economy was heading fast into the 2001 recession.

The Fed began to aggressively lower interest rates. This was precisely how Chairman Greenspan said the Fed should respond to a bursting investment bubble. Greenspan had laid out his position in a June 1999 appearance before Congress’s Joint Economic Committee. He argued that policymakers could not accurately identify bubbles until after they had burst and, thus, should not try in advance to deflate them: “Bubbles generally are perceptible only after the fact. To spot a bubble in advance requires a judgment that hundreds of thousands of informed investors have it all wrong. Betting against markets is usually precarious at best.”

Greenspan believed the Fed should respond aggressively after the fact, lowering rates only when a bursting bubble appears to threaten the economy. “While bubbles that burst are scarcely benign, the consequences need not be catastrophic,” Greenspan said. Japan’s bubble economy burst in the late 1980s, but that country’s failure to react promptly, not the bubble itself, caused the decade-long recession that followed. Similarly, the Great Depression of the 1930s arose not from the stock market crash of 1929, but from the government’s failure to manage the aftermath.

Greenspan argued that his decision to lower rates aggressively in the wake of the October 1987 stock market crash had kept that financial crisis from ending the economic expansion of the 1980s. Similarly, dramatic rate cuts in 1998 seemed to have successfully limited the fallout from the collapse of hedge fund Long-Term Capital Management. These experiences had shaped his thinking about how to handle the tech-stock bust.

These words and actions strongly suggested to Wall Street that the Fed would stop any future market mishap from becoming a complete financial meltdown—that, in effect, the chairman had their proverbial financial backsides covered. Commentators called this notion “the Greenspan put,”9 using a term from the options market. A “put” option gives its owner the right to sell a stock or bond at a preset price, offering protection against future drops in the market. Greenspan’s “put” was an implied promise that if things ever went badly awry for Wall Street, the Fed would step in and cut rates enough to cushion the fall. It wasn’t a guarantee that investors couldn’t lose money, but it did suggest that they wouldn’t lose their shirts.

Greenspan’s conviction that the Fed should not prick bubbles, but rather should wait to clean up the economic mess after they burst, contributed significantly to the subprime financial shock. So did his belief that housing markets, unlike stock markets, were largely bubble proof. He spelled this out in a March 2003 speech:10

It is, of course, possible for home prices to fall as they did in a couple of quarters in 1990. But any analogy to stock market pricing behavior and bubbles is a rather large stretch. First, to sell a home, one almost invariably must move out and in the process confront the substantial transaction costs in the form of brokerage fees and taxes. These transaction costs greatly discourage the type of buying and selling frenzy that often characterizes bubbles in financial markets. Second, there is no national housing market in the United States. Local conditions dominate, even though mortgage interest rates are similar throughout the country. Home prices in Portland, Maine, do not arbitrage those in Portland, Oregon. Thus, any bubbles that might emerge would tend to be local, not national, in scope.

Deflation Fears

Greenspan’s position on house price bubbles was not simply an academic debate; it was part of the intellectual foundation of his strategy for handling the apparent trend toward deflation in the wake of 9/11. The turmoil that followed 9/11 gave the Fed no option but to lower rates aggressively. Yet despite this aggressive response and the massive Bush tax cuts, the economy continued to sputter. As American forces were preparing to invade Iraq in spring 2003, deflation was Greenspan’s predominant worry.

He described the economic pain of deflation in a late 2002 speech before the Economic Club of New York.11 Deflation, he feared, would undermine incomes and profits, making household and business debt loads financially overwhelming. The resulting credit problems and bankruptcies would feed further deflation, launching a vicious cycle. The Fed chairman calculated that the economy’s only chance of avoiding such a deflationary trap was an unprecedented 1% funds rate.12 This, he reasoned, would ignite a housing boom without creating a housing bubble.

Greenspan’s strategy worked. As interest rates fell, the housing market took off and lifted the economy into a self-sustaining economic expansion. By 2004, home sales, housing starts, and housing prices were surging. Thousands of jobs were being created in housing-related industries, and other industries were adding to payrolls as well. Deflation quickly faded from the economic lexicon.

The irony is that deflation wasn’t the grave threat Greenspan feared. His worries were based on data from surveys that are subject to revisions—sometimes large revisions. It turned out that inflation did slow during this period, but as the revised data later showed, it slowed not nearly as much as Greenspan and others thought (see Figure 4.3).13 Perhaps it is just as difficult to know how the economy and inflation are performing as it is to know if a bubble is forming. Equally ironic is that Greenspan thought dispelling deflation was necessary to ensure that debt loads wouldn’t crush overextended households and businesses. As it turned out, the borrowing boom that Greenspan ignited created its own, perhaps equally damaging, credit debacle.

Figure 4.3 Deflation wasn’t the threat feared: inflation, % change a year ago, core personal consumption expenditure deflator.

Households on a Buying Binge

Greenspan was counting not only on an interest-rate-juiced housing market to pull the economy out of its post–9/11 malaise, but also on the hedonism of the American consumer. With housing prices and housing wealth rising quickly, and homeowners able to cheaply tap that wealth for ready cash, his expectations turned out to be well founded.

A well-established economic theory known as “the wealth effect” states that as your wealth increases, you will spend more and save less. The more your assets—a house, a retirement fund, a child’s college fund—appreciate in value, the more willing and able you will be to spend your current income. Not only does the theory make intuitive sense, but it also has proved true in practice. And once again in the 2000s, as housing prices and housing wealth soared, homeowners became more avid spenders.

Although economists accept that the wealth effect exists, they do debate its size. How much does increased housing wealth add to spending? Estimates vary, but given more than $8 trillion in increased housing wealth during the boom, even a very small wealth effect implies a lot more spending.14 Suppose that for every $1 increase in housing wealth, consumer spending subsequently increased by only a nickel—a conservative estimate of the effect. The housing boom then added more than $75 billion a year to consumer spending—enough to raise the economy’s overall rate of growth by half a percentage point every year.

It’s actually likely that the housing wealth effect was measurably greater than 5¢ per dollar and that the traditional pattern was super-charged as homeowners withdrew massive amounts of cash from their homes. For many, their house became another ATM. Greenspan thought the topic was so important that he personally conducted research published in Federal Reserve working papers.15

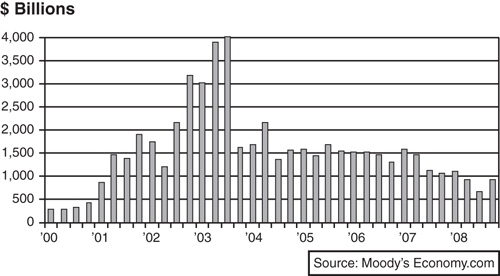

Homeowner cash withdrawals began to rise early in the decade via an unprecedented wave of mortgage refinancing. As fixed mortgage rates plunged from more than 8% to less than 6%, nearly anyone with a mortgage could profitably refinance it; they could quickly make up the transaction costs of the refinancing by saving the interest on the new mortgage.16 These transaction costs were also falling fast, thanks to roaring competition among mortgage lenders and the spreading use of the Internet to reduce loan processing costs. In 2000, the value of all U.S. home-refinancing deals totaled less than $300 billion; as the refinance (refi) boom peaked three years later, the annual pace of such deals topped $4 trillion (see Figure 4.4).

Figure 4.4 Mortgage refinancing boom: value of mortgage refinancings.

The cost saving to homeowners was enormous. On the mortgage loans refinanced in 2003 alone, homeowners were cutting their interest expenses by more than $50 billion a year. Homeowners were also using their refis to raise cash. In a cash-out refi, the homeowner takes a new and bigger loan, pays off the original mortgage, and gets a check for the difference. Because mortgage interest rates were falling, the new, larger mortgage didn’t necessarily require a larger monthly payment. Homeowners cashed out an estimated $100 billion in the 2003 refi boom. This was a bonanza for consumers, who used some of the cash to pay down higher-cost credit card debt and finance other investments, but spent most of it on home improvements, cars, or anything else they could shop for.

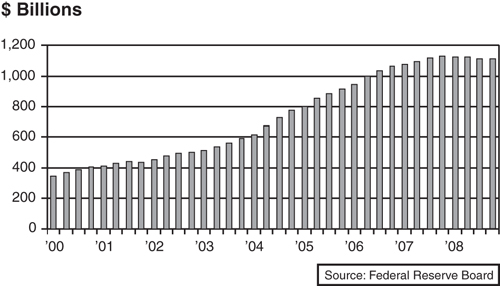

Homeowners also raised hundreds of billions via increased home equity borrowing. With interest rates low, homeowners could cheaply borrow against the value of their homes, either taking a lump-sum check with a second mortgage or setting up a home equity line of credit up to a set amount—the average was $20,000.17 The amount of home equity debt surged four-fold during the first half of the decade, from $200 billion to $800 billion, with homeowners tapping their houses for cash as they did through cash-out refinancing (see Figure 4.5).18

Figure 4.5 Home equity borrowing soars: home equity loans outstanding.

The housing boom also prompted many homeowners to cash out by trading down—selling their homes at a high price and buying smaller places or even renting. Empty nesters, in particular, saw this as an opportune time to take a capital gain. In resort communities, some homeowners seized the opportunity to sell their properties to developers or investors for large profits. Some long-term residents of New Jersey beach towns, for example, moved to less expensive homes inland. They reinvested much of the resulting profits, creating comfortable family nest eggs—but they also spent some.

The Federal Reserve’s dramatic interest-rate cuts had worked. Instead of remaining in a slump after 9/11 and the Afghan and Iraq invasions, the U.S. economy recovered. But that growth was built on a housing boom—a boom that ultimately became a bubble. Chairman Greenspan had expected the boom, but he had not counted on the bubble—and he certainly hadn’t expected what came afterward.

To this day, former Chairman Greenspan rejects the notion that his aggressive lowering of interest rates earlier in the decade helped contribute to the subprime financial crisis. Indeed, it is reasonable to argue that based on the apparent threat of deflation at the time, it was necessary for the Federal Reserve to act forcefully. It is even understandable why Greenspan felt that the most efficacious way to lift the broader economy was through a booming housing market. But it is wrong to argue that these policies did not contribute to the crisis that subsequently ensued. They did.