5. Global Money Men Want a Piece

The Greenspan-led Federal Reserve wasn’t the only source of easy money powering the housing boom and inflating the bubble. A flood of capital also poured in from around the world. Global investors thought U.S. housing was a great investment. Their funds drove mortgage rates lower and empowered lenders to offer increasingly aggressive—and, ultimately, unmanageable—mortgage loans.

International investors were flush with dollars that the swollen U.S. trade deficit generated. Hundreds of billions of dollars flowed overseas each year in exchange for the imported goods Americans craved.

U.S. consumers had been on a buying binge, fueled by the Federal Reserve’s rate cuts, the massive Bush tax cuts, and all the credit they needed. Imports, in particular, were bargains, thanks to an explosion of low-cost Chinese production and the high-flying U.S. dollar. Surging prices for oil and other commodities, driven in part by booming Chinese demand, also added to the import bill. As a result, investors in places from China and India to Russia and Brazil were collecting huge pools of dollars.

For these newly flush global money men (and women), the bonds and other credit market securities Wall Street devised seemed to be perfect investments. Global investors could match the amount of risk they were willing to take with an instrument tailored to provide it—or, at least, that’s what they thought. And the U.S. bond market was huge, liquid, and historically safe. Liquidity showered U.S. credit markets, pushing interest rates lower.1

It didn’t take long for global investors to become especially enamored with mortgage-backed bonds. Foreigners had historically been buyers of risk-free U.S. Treasuries, and the bonds government-tied institutions such as Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac issued and insured were only a small step removed. It wasn’t much of a leap to invest in mortgage securities whose ties were to Wall Street instead of to the U.S. government.

A self-reinforcing cycle developed: American consumers were eager to buy and the rest of the world was happy to sell, producing the goods Americans wanted and collecting their dollars. But those dollars didn’t stay overseas; they reentered the U.S. economy as investments in a broad array of financial securities—none more popular than mortgage-backed bonds. As foreign investors bid up the prices of those bonds, they pushed interest rates lower, following the rule of all debt securities that price and yield move in opposite directions. The lower interest rates were passed along to mortgage borrowers, and competition among lenders led to easier lending terms as well. Cheap and easy credit spurred more home purchases and still more borrowing and spending. The cycle was complete.

The easy-money policies of most central banks also revved up the global cash engine. Most economies had struggled in the wake of 9/11 and the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan and Iraq, and their manufacturers were withering under the onslaught of Chinese competition. With inflation giving way to deflation, they had a green light to slash interest rates. The Japanese were particularly panicked after more than ten years of economic malaise; they pushed their interest rates literally to zero. Cash was everywhere.

At first, investors were skittish about the U.S. stock market after the technology-stock bust. They also had qualms about investing in emerging economies, remembering the late-1990s Asian financial crisis and Russian bond default. But these concerns quickly faded. By the mid-2000s, investors acted as if the stock, bond, and real estate markets were full of screaming buys. The enthusiasm was even greater if they could be bought with borrowed money.

By early summer 2007, risk taking in global financial markets had reached unprecedented levels. Global investors were taking huge gambles and paying premiums for the privilege. All the preconditions for a major financial upheaval were in place.

China Muscles In

Where did all this global capital come from, and why did so much of it end up in the U.S. housing market? The answer begins in China at the turn of the millennium, just as the new Chinese economy was bursting onto the global stage.

The catalyst for China’s stunning economic ascent was its entry into the World Trade Organization (WTO). Membership in the international organization that sets the rule for trade among its members conferred economic advantages of lowering barriers and opening doors. It also signaled that a country mattered—that it had a seat at the table of global commerce. The Chinese leadership had long lobbied to join the WTO, and it finally happened in 2001.

Entry into the WTO significantly opened up global markets for China’s goods. For increasingly footloose global manufacturers, it meant new or expanded opportunities to hire hundreds of millions of Chinese workers on better terms than could be obtained anywhere else on the planet. Combined with a fixed and increasingly undervalued currency, the yuan, this made China the lowest-cost location to produce goods for the rest of the world.2

China’s manufacturers received another big lift in 2005, when the 20-year-old multifiber trade agreement expired. This trade treaty had limited the exports of textiles and other garments from developing economies such as China to the United States and other developed economies. With its expiration, shipments from low-cost Chinese producers surged.3

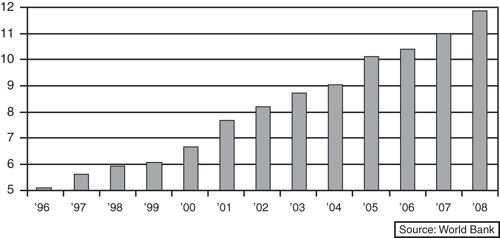

In the mid-1990s, China was a small player in the global economy, but within ten years, it was producing more than one-tenth of the globe’s manufactured goods (see Figure 5.1). China’s gains came at the expense of manufacturers everywhere else: Apparel, textile, and furniture producers in the Southeastern United States were hit hard, as were lower-end producers in Mexico and Central America. Even Italian producers of fine consumer goods struggled. Because manufacturing is so important to most global economies, China’s rapid grab of global market share caused wrenching adjustments in many places around the world.

Figure 5.1 China blows onto the economic scene: Chinese share of global manufacturing.

Outside of China, the principal beneficiaries of the country’s ascent were American consumers. No other nation produced more items for U.S. store shelves than China; by 2008, more than one-tenth of America’s imported consumer goods were crossing the Pacific and through the ports of Los Angeles or Seattle.4 Big U.S. retailers—most notably Wal-Mart—showed themselves extraordinarily adept at setting up efficient supply chains: from Chinese factories, to container ships, to U.S. shopping malls or Internet catalog sites. Prices plunged. The cost of Chinese-made products, from sweaters to computers, plunged by 20% during the first half of the decade, enabling U.S. retailers to actually lower the prices on the goods they sold to consumers. Inflation had given way to deflation—outright declining prices—in most stores.

These bargains were too good to pass up. As consumers scarfed up the deals, the nation’s import bill and trade deficit ballooned. The red ink in U.S. trade with China was $50 billion when 2000 began; by 2008, it totaled a whopping $250 billion. Trade with China alone now accounts for almost one-third of the total U.S. trade imbalance.

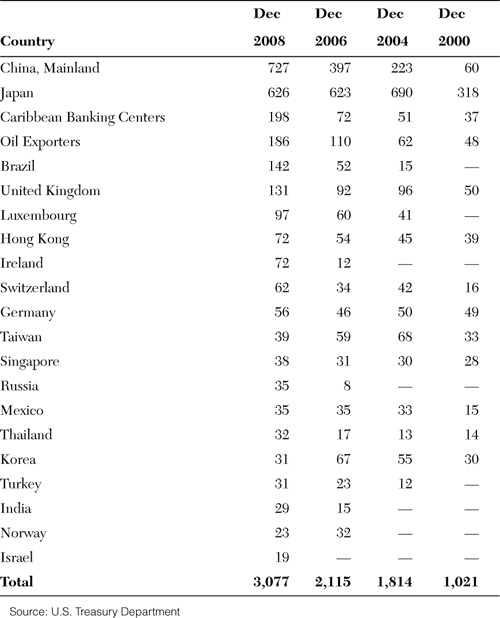

The Chinese were initially unsure of what to do with their new riches. Investment had been anathema under Mao, and few mainland residents, even among the government elite, had any idea how to go about it. The easiest and most obvious place to put U.S. dollars was in U.S. Treasury bonds. They were safe and liquid, and didn’t require much financial sophistication to understand. The Chinese were similar to any young person earning a salary for the first time; they wanted to make sure they had cash socked away for a rainy day. In a sense, U.S. Treasury bonds became China’s certificates of deposit. And before long, China had a lot of them—almost $500 billion, or about a tenth of all the Treasury bonds in circulation, by mid-decade.5 Only the Japanese owned more, although that has since changed: The Chinese stake has continued to rise, while the Japanese are no longer adding to theirs (see Table 5.1).6

Table 5.1 Foreign Holdings of U.S. Treasury Securities (Billions $)

As China’s nest egg grew larger, its financial expertise and infrastructure grew, enabling it to make bigger and bolder investments. A ten-year Treasury bond yielding 4% is fine when all you want is safety, but a 4% return looks paltry when you are rolling in cash and your own economy is growing at more than twice that pace. The Chinese began to expand their portfolios to include U.S. agency bonds—debt issued by Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and the Federal Housing Finance Board—to fund their own purchases of U.S. mortgage loans and securities. Although the U.S. government did not officially back these bonds, they were all but guaranteed. However, the return on agency bonds soon began to look lame to the Chinese. They began to pay attention when Wall Street’s emissaries came calling to pitch other investments: corporate bonds, residential mortgage securities, and eventually even exotic derivatives such as collateralized debt obligations.

When it came to residential mortgage securities and their derivatives, Wall Street’s story line was particularly convincing to the Chinese: Trillions in dollars of residential mortgage loans had been made to U.S. homeowners during the previous half-century, and the losses on those loans could be counted in basis points—in hundredths of a percentage point. Yes, home prices had declined in some parts of the country, but only briefly and temporarily; since the Great Depression, nationwide price declines had never existed. And the securities the Chinese were buying had been structured so that they would always get their money back, according to the rating agencies so revered by international investors.

Emerging Investors

The Chinese weren’t the only global investors piling into U.S. credit markets. Other emerging economies—nations whose populations were still poor but whose living standards were rising fast—were also suddenly flush. Globalization had been good to them; about half of global production was now coming from emerging economies such as Brazil, India, Poland, and Russia.7

Soaring prices for the oil and other commodities they produced also lifted these economies.8 The average cost of crude soared from $20 per barrel at the start of the 2000s to an all-time peak of over $150 in summer 2008; other raw-materials prices, from copper to soybeans, also jumped. This was due to booming Chinese demand; China needed commodities to drive its factories and feed its expanding middle class. Because international buying and selling of commodities was mostly done in U.S. dollars, emerging economies were showered with greenbacks, and as with the Chinese, they thought a U.S. bond was a great investment.

The sums earned in trade were massive. The U.S. trade deficit with emerging economies swelled from $150 billion a year in 2000 to more than $350 billion in 2008. Half this increase was with OPEC nations—the big oil-exporting countries upon which the globe relies for much of its energy—whose Treasury bond purchases increased in lockstep with the dollars they raked in as the price of oil rose. The other half was with oil and natural gas producers such as Russia, copper producers such as Chile, coffee exporters such as Columbia, plywood producers such as Indonesia, and so on.

Developed economies weren’t left out of the action; they, too, were taking in large amounts of dollars in trade with the United States. Only a few years earlier, the dollar had been trading near record highs against the euro, the British pound, the Canadian looney, and the Japanese yen. The lopsided exchange rate had made these nations a bargain for U.S. tourists and U.S. importers alike. Dollars flew from American pockets to British, Canadian, and Japanese cash registers; the U.S. trade deficit with these economies doubled to $200 billion annually during the first half of the decade. Investors in London, Frankfurt, and Tokyo are wealthy and experienced, and they were more interested in investments offering high returns than safe investments. Treasury bonds wouldn’t suffice; their yields were much too low. More complicated U.S. credit instruments, such as mortgage-backed bonds and their derivatives, filled the bill.

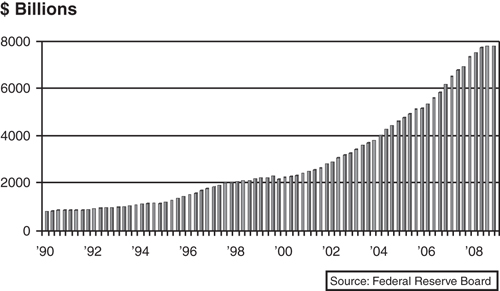

If we add up the hundreds of billions of dollars that flowed out of the United States in trade and then back in as investments in U.S. credit markets, we can clearly see the magnitude of global investors’ contribution to the housing bubble. The U.S. trade imbalance was without historical comparison; the deficits doubled during the first half of the decade, reaching a record $800 billion in 2006. All those billions flowing overseas each year financed a three-fold surge in the foreign holdings of bonds, to an astonishing $6 trillion (see Figure 5.2). Overseas investors’ Treasury holdings more than doubled and were on pace to become the majority owner of all publicly traded U.S. Treasury debt. The foreign appetite for mortgage-backed bonds was even larger; overseas holdings of agency-related debt and Wall Street–issued mortgage securities swelled. At the peak of the housing boom in 2006, international investors owned nearly one-third of all U.S. mortgages.

Figure 5.2 International investor holdings soar: credit market instruments held by foreigners.

Central Banks Pump It Up

The extraordinary easy-money policies pursued by most of the globe’s central banks also helped pump up the U.S. credit and housing market. Fallout from 9/11 and the U.S. invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq had hit the global economy hard early in the decade. Europeans were still absorbing the formerly Communist states of the East into their economic community and adjusting to their newly adopted currency, the euro. Much of Central and South America had recently reformed those national economies, and Southeast Asia was still recovering from its late-1990s financial crisis.

China’s rapid economic ascent created new challenges for nearly everyone. Although the burgeoning mainland economy lowered prices for global consumers, it also destroyed the profits and jobs of its competitors. Not only were higher-cost developed economies such as the U.S. and Germany losing market share to China, but so were developing economies such as Mexico or Poland, where production costs were low—but not as low as in China.

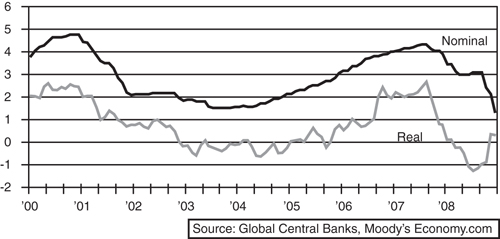

Central bankers tried to ease the pain of all these adjustments by cutting rates. With a flood of cheap Chinese goods helping to lower inflation, policymakers had the latitude to reduce borrowing costs dramatically. The U.S. Federal Reserve led the way, but most other central banks soon followed. The Bank of England, the fledgling European Central Bank, the Mexican Central Bank, and the Bank of Canada all lowered rates. The average global central bank target interest rate declined from a peak of 5% in late 2000 to a low of 1.5% in 2003, where it stayed throughout much of 2004 (see Figure 5.3).9 Even more telling was the negative real central bank target rate—the difference between the stated rate and inflation. (If the benchmark interest rate is 1.5% but inflation is 2.5%, the real rate is –1%—a condition at least theoretically attractive to borrowers.) Central bankers have historically reserved negative real rates for times of economic crisis or recession. The global real rate went negative in 2002, and it didn’t turn positive again until well into 2006.

Figure 5.3 Global central banks pump it up: average central bank target rate.

No central bank was pumping out more cash than the Bank of Japan. China’s success rocked the Japanese economy. Japan had been the global export powerhouse in the 1970s and 1980s, but its bigger problems stemmed from the collapse of Japan’s real estate and stock markets. A speculative bubble had developed in Japanese asset markets in the 1980s; as it unraveled during the 1990s, bad loans piled up in the country’s banks. The banks took years to recognize their mistakes, refusing to write off their bad loans and tying up what capital they had. A long, painful credit crunch ensued, making it hard for even healthy businesses to expand their operations or for households to spend. With the Japanese economy moving sideways and deflation a persistent fact of life, the Bank of Japan steadily lowered rates. By the early 2000s, the rate targeted by the Japanese central bank was nearly zero—0.10%, to be more precise—and Japanese policymakers insisted it would stay that way for as long as it took to revive their economy and rid themselves of deflation.10

Global investors quickly devised a way to take advantage of Japan’s zero-interest-rate policy: They borrowed yen in Japan and then traded the yen for dollars, euros, or Australian dollars—any other currency that seemed safe and offered better returns when invested. This became known as the yen carry trade. The trade was profitable as long as the yen stayed weak; investors could trade their higher-yielding dollars or euros back into yen, repay their loans, and pocket the difference. The Bank of Japan’s steadfast promise not to change its monetary policy made a weak yen a safe bet. Trillions of yen poured out of Japan and into investments across the globe; U.S. credit markets and housing received a fair share.

A Global Sea of Liquidity

By mid-decade, a sea of cash was washing over global asset markets. Investors couldn’t get enough of whatever was for sale, wherever it was. Stocks, bonds, and real estate in Moscow, Beijing, or Los Angeles all seemed to offer buying opportunities, and prices rose sharply.

Even the professional investors who managed global pension funds, insurance companies, and hedge funds were swept up in the excitement. Initially, skeptics argued that markets were becoming overpriced, and for a time they were heeded; the financial pain of the tech-stock bust and the Asian financial crisis had not been forgotten, and most of the signals used to value investments were flashing red. However, as asset prices continued to march higher, those arguing that something was askew in global asset markets steadily lost credibility. Eventually, they either changed their minds—skepticism could be bad for your career—or their views were dismissed as simplistic and impractical.

A few academics and policymakers—mostly at central banks—continued to warn that investors were taking on too much risk and that global markets were overheating. But the realities of the investment world dictated: If a manager is given money to deploy, he must deploy it or the money will go elsewhere. Managers are evaluated based on the returns they bring relative to their peers, not over several years or even over a single year, but over the space of a quarter—three short months. Life can get very lonely for a cautious investment manager in a runaway market.

Some hand wringing at investor conferences about rising global asset prices and aggressive risk taking did occur. Professional investors had a general sense that someday a market correction would bring asset prices back down modestly. But as time went on, those discussions grew increasingly theoretical and less relevant to the actual investment decisions being made.

A mounting intellectual defense of lofty global asset prices existed among managers searching to make sense of their investment decisions. This time it was different—or so the argument went. Never before had the global economy been this stable or this open. In the new economic world, business cycles might be milder and briefer than they had been historically. Ups and downs in employment and income, corporate profits, landlords’ rents—conditions that determined the value of mortgage-backed bonds, corporate shares, or the price of an office tower—were growing progressively less volatile.

What some called the Great Moderation was driven by a shift in economic activity to more stable industries, such as information and health services, and away from businesses that suffer bigger swings, such as manufacturing. Better and timelier business decisions, resulting from the use of new information technologies, made it less likely that firms would misjudge their sales and get stuck with excess inventories, forcing production and job cuts. A more globally integrated economy ensured that countries suffering an economic setback could sell their wares to stronger ones, thereby cushioning their problems. Public policy was also smarter; governments and planners were better at managing their economies. As an example, most central banks had been granted enough political independence to pursue what could be unpopular efforts to achieve the explicit inflation targets they had adopted.

Global investors also took comfort in the cornucopia of new investments now available—collateralized debt obligations, collateralized loan obligations, leveraged loans, credit default swaps, auction-rate securities, and so on. These Wall Street concoctions were thought to more finely parse the risks of investing than a plain-vanilla stock, bond, or parcel of real estate could do. Risk could be more easily hedged, matched with other investments that would rise or fall in value in roughly the opposite direction. Hedging could limit gains on an investment, but it would also limit losses—or so money managers thought. Investors believed they could sign up for precisely as much risk as they wanted—no less and, importantly, no more.

Investors were emboldened. A more stable global economy meant more stable returns, and the new designer investments enabled them to fit their needs with precision. Feeling secure, their inclination was to magnify their returns through leverage—they borrowed money to buy even more of whatever they were investing in. Leverage can generate extraordinary returns if the bet works out, but it can be financially devastating if it doesn’t.

The typical money manager acted similar to the owner of an oversized SUV with a five-star safety rating. He felt safe not only driving fast, but also chatting on his cell phone at the same time. More crashes might occur, yet the SUV driver will suffer no more bodily injury than if he had driven more carefully in a smaller car with only a three-star rating. For other drivers, however, the damage would be substantially worse.

The liquidity sea also filled with new money—savings that had been locked away in different corners of the world and only now was finding its way into the global financial system. Similar to others, the owners of these funds were attracted by rising asset prices, the stable economy, and the risk matching afforded by designer investments. Many nations also began to remove the limits on their citizens’ ability to invest outside their borders. For the first time, a Japanese or Finish saver could invest in Irish stock or a Fannie Mae bond.11

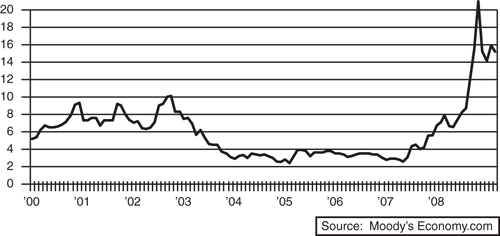

Euphoria in global asset markets reached an apex in the weeks leading up to the subprime financial shock in summer 2007. In most countries, stock prices, commercial property values, and prices for most bonds had risen to record highs. Investors had never been willing to pay so much to get so little. The tie between stock prices and corporate earnings—called the price-earnings (PE) ratio—went skyward in most emerging economies.12 The ratio of rental income to commercial real estate prices—called the capitalization rate—hit record lows in most developed economies. The yields on most bonds compared with yields on risk-free Treasuries—known as the yield spread or the risk premium—was wafer thin, particularly in the United States (see Figure 5.4).

Figure 5.4 Investors asked for little compensation: yield spread between junk corporate bonds and treasuries.

By the time the financial shock hit, global asset markets were awash, even drowning, in a sea of liquidity. Investors had driven up prices for all assets, had taken on leverage, and were still desperate for something to invest in that would generate a sufficient return. U.S. credit markets—in particular, securities backed by residential mortgages—were attracting more than their share of investors. All the preconditions for a financial shock were in place, with American homeowners in the middle.