9. Learning to Love Debt

Financial alchemy took the form of more and more borrowing, initially in the form of private equity and junk bonds. Private equity, originally called leveraged buyouts (LBO), was about high levels of leverage—debt. Investors, financial sponsors, committed a small amount of the capital required to buy a company. The bulk was borrowed and repaid from the cash flow of the acquired business. The game was buying low and selling high, with other people’s money.

Fixed Floor Coverings

Congoleum traced its origins back to the American Nairn Linoleum Company, established in 1887 in Kearny, New Jersey. The company manufactured linoleum, a durable floor covering made from solidified linseed oil, pine rosin, ground cork dust, wood flour, and mineral fillers on a burlap or canvas backing.

In 1978, Congoleum had $576 million of revenue and $42 million in earnings. 40 percent of revenues and 53 percent of earnings came from linoleum. The rest came from ship-building and automotive accessories. The company had negligible debt. Congoleum shares traded at a current market price of $25.375, equivalent to seven times price/earnings ratio (share price divided by current earning per share—EPS).

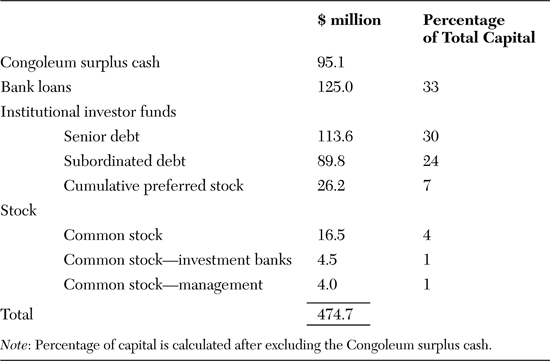

On July 16, 1978 First Boston (now part of Credit Suisse) and insurer Prudential Insurance Company offered $474.7 million to purchase Congoleum at $38 per share, 50 percent above the market price, financing the purchase with 87 percent debt (see Table 9.1).1

Table 9.1. First Boston’s Offer to Purchase Congoleum

The purchase was less risky than it appeared because the company’s stable earnings and cash flows could support increased debt repayments. Following the LBO, according to First Boston’s forecast, Congoleum’s interest coverage (interest payable divided by earnings before interest and tax—EBIT) would be 1.7 times. Earnings would have to fall by 41 percent before it would have difficulty meeting interest payments. Although this was a low margin of safety, Congoleum’s interest coverage would improve rapidly as it paid off debt. By 1984 one-third of its borrowing would be repaid and interest cover increased to around 4.6 times—an excellent margin of safety. Patents and royalty arrangements protected earnings from the floor covering business. The shipping business had a backlog of orders and contracts with its clients, including the U.S. Navy.

Following the successful acquisition of Congoleum by First Boston, the firm, in fact, reduced borrowing ahead of schedule by 1983. Congoleum then underwent a new LBO. In 1986 management liquidated Congoleum, selling off the businesses separately for $850 million, an increase in the company’s value of 175 percent in 7 years. The managers turned their $4.0 million investment in Congoleum into nearly $600 million. Byron Radaker and Eddy Nicholson, who had managed Congoleum since 1975, announced: “We expect to build another company or make some interesting investments in the future. Before we’re going to make any decisions we’re going to take a rest.”2 For everyone, it was one huge payday, all done with leverage.

By the Bootstraps

LBOs are synonymous with KKR (Kohlberg, Kravis, and Roberts) and their $31.1 billion LBO of RJR Nabisco, chronicled in the 1990 book Barbarians at the Gate: The Fall of RJR Nabisco. In 2006 and 2007, larger LBOs were completed although, after adjustment for inflation, none surpassed RJR Nabisco.

While at investment bank Bear Stearns, Jerome Kohlberg, Jr. and his protégés Henry Kravis and George Roberts, a cousin of Kravis, purchased businesses for financial buyers using large amounts of debt. After strategic disagreements, the three left Bear Stearns, creating KKR in 1976.

LBOs were not new. After the Second World War there were bootstrap acquisitions where financial buyers bought businesses, using the acquired company’s assets and cash flows to pay for the purchase. In the 1960s, James Ling and his investment conglomerate LTV purchased companies using high levels of debt, selling off the parts for profit. Ling’s modus operandi was simple: “Jimmy looked for value.... Here’s an undervalued company. [He] could leverage the whole thing and the company could buy itself.”3

During the 1970s, with the global economy mired in low economic growth, high inflation, and high unemployment, LBO volumes grew steadily. Many were purchases of unwanted or underperforming businesses, or smaller companies whose shares were undervalued due to lack of research coverage, limited liquidity, and their unfashionable businesses. Hastily assembled conglomerates from the 1960 go-go years also needed restructuring.

LBO firms gobbled up quiet companies with reliable earnings and cash flow. Financial buyers and a stake for existing management and staff were attractive to a retiring generation of founders of family-owned businesses. Corporate managers who had experienced the Great Depression first hand and shunned debt were literally dying off. The new managers, many with MBAs, were more willing to borrow.

In January 1982, an investment group headed by William Simon, a former U.S. Treasury secretary, acquired Gibson Greetings, a producer of greeting cards, for $80 million. Some 16 months later the investors floated Gibson on the stock market for $290 million. Simon turned an investment of around $330,000 into approximately $70 million. The success of Gibson Greetings and the huge returns attracted attention, triggering a boom in LBOs.

Leverage for Everything

True believers argued that LBOs empowered management to improve operations and efficiency, increasing earnings, and the value of the business. The popular Boston Consultant Group (BCG) growth-share matrix categorized businesses as “stars,” “cash cows,” “question marks,” and “dogs.” Good management took funds generated by cash cows to invest in stars or question marks with higher growth and earnings potential. LBOs used debt to convert cash cows, question marks, and even dogs into stars—the economic equivalent of kissing the frog to turn it into a prince.

Assume you buy a company for $100 million using $10 million of equity and borrowing $90 million at 6 percent per annum. The company produces cash of $15 million each year. If you pay no dividends and do not invest in the business, diverting all the cash ($15 million) to paying back debt, then you are debt free in 8 years. If you can sell the business for the original value, then your $10 million investment is now worth $100 million, a return of 33 percent per annum. If you can extract more cash from the business, then you pay down the debt quicker, increasing returns. If cash flow increases by one-third to $20 million per annum, then debt is repaid in 6 years, increasing returns to 46 percent per annum.

Investors in Congoleum paid a premium of $154 million (50 percent over the market share price before the First Boston offer). Cost-savings from becoming a private company and large tax benefits accounted for most of the premium paid. Savings from avoiding the costs of being a public listed company were around $11 million over 5 years in 1979 dollars. Congoleum’s tax deductible interest deductions were equivalent to $78 million. Congoleum’s assets were written up to fair market value, increasing depreciation expenses and generating additional tax savings worth $50 million over 5 years. These savings, totalling around $139 million, made up most of the extra amount that First Boston was willing to pay.

Franco Modigliani and Merton Miller had identified that firms with larger borrowings benefited from the lower cost of debt and tax savings, because they were able to deduct the interest payable. Debt, they argued, should be increased to a point where the risk of bankruptcy was manageable to increase returns to shareholders. LBOs were a practical application of this insight. In July 1909, during a debate on introducing corporate income tax and making interest expenses tax deductible, U..S Senator Augustus O. Bacon prophetically noted: “It will be within the powers of corporations to convert their stock into bonds...in so doing, they will escape the payment of this tax.”4

LBOs did not rejuvenate firms or improve them. John Brooks, a journalist, contrasted acquisitions of the conglomerate era of the 1960s and the LBOs of the 1980s: “the acquirers...in the sixties intended to operate them or let them operate themselves, those of the eighties...seemed...to be for the purpose of dismantling them...for a quick-cash profit.”5 One financier used rhapsodic language: “It’s the leverage. What we are really doing is releasing value the way a sculptor releases a work of art from a block of stone.”6 LBOs were not art; they were about milking the cash cow.

Cutting to the Bone

Between 1979 and 1989, more than 2,000 LBOs, worth in excess of $250 billion, were completed. KKR and its competitors created investment funds to invest in their deals.

The size of the deals grew rapidly. Increasingly, the acquisitions were unfriendly—hostile and unsolicited bids. When KKR considered an unsolicited offer, Kohlberg protested: “It’s not the way of the firm.”7

Initially, transactions stuck to the script, focusing on businesses with strong, stable cash flows that were able to support debt. Over time, the margin of safety declined. Congoleum’s interest coverage of 1.7 times was considered aggressive. By the late 1980s, the coverage ratios were around 0.7 times, meaning borrowers would have difficulty even paying interest.8 Health warnings, risk factors, relating to LBO debt, stated that: “funds generated by the existing operations will be insufficient to enable the Company to meet its obligations on its borrowings.” It was no longer a case of milking the cow.

Under innovative debt structures, interest was accrued but not paid in cash. It would be paid when assets were sold or from money raised by selling shares. The lenders were attracted by the higher interest rates, ignoring whether they would receive anything at all. LBOs now relied on paying down debt from selling assets, cost cutting, reducing business investment, and other corporate auto-cannibalism: “We’re always cutting, cutting, cutting.... There’s the risk that you may cut out something that you really need.”9

In the 1980s, corporate raiders—T. Boone Pickens, Carl Icahn, Victor Posner, Robert M. Bass, Kirk Kerkorian, Sir James Goldsmith, Saul Steinberg—dominated LBOs.

Boone Pickens made a series of raids on major oil companies, realizing that they were literally liquidating themselves by depleting their reserves without investing in exploration and development to replenish them. Pickens was unsuccessful but earned significant profits by building up strategic stakes in companies like Cities Services, Gulf Oil, and Unocal, effectively putting them into play. It was simple greenmail, the use of the threat of a hostile takeover to coerce management into buying off the potential bidder. Pickens profited from selling out his stake to either white knights arranged by the board or sometimes to the company itself, which borrowed to buy back its own shares from the unwelcome intruder.

After leaving to set up his own buyout firm, Kohlberg staked out the high moral ground, speaking out against “overpowering greed” and the breakdown in Wall Street’s ethical system. But Kohlberg, a “spiritual leader” questioning the evolution of the industry, continued to make millions of dollars from his investments in KKR transactions and preferential rights to invest in new transactions, including RJR Nabisco.10

Professor Jensen Goes to Wall Street

Professor Michael Jensen, a prominent evangelist of the Chicago School, argued that LBOs improved the efficiency of firms.11 The discipline of debt, the obligation to make interest and principal payments, forced operational improvements. Substitution of expensive equity with cheaper debt lowered the businesses’ cost of capital. Managers with meaningful equity stakes behaved like owners maximizing shareholder value, better aligning the interests of managers and shareholders. Private firms, protected from the pressures of meeting quarterly earnings targets, and the threat of takeovers, could be managed for the long term.

Critics saw LBOs as financial opportunism, exploiting tax benefits. Operational benefits of LBOs were limited and not the real motivation. They argued that lenders misunderstood risk and underpriced the debt.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, American industry was embattled as stagflation and increased competition, especially from Japan and Germany, squeezed profitability. Product quality was often poor, costs high and sensitivity to customer requirements absent. Businesses needed radical reinvention to become competitive and viable.

Like BCG, Jensen focused on free cash flow—the surplus cash from operations after reinvestment to maintain or renew capacity where it was profitable. In periods of growth, firms achieved high returns but needed cash. High returns came from strong demand, high prices, in part driven by a shortage of production capacity to meet this demand, and limited competition. Cash shortfalls reflected the need to constantly invest in plant, equipment, working capital, and human resources to grow. As the market for a product matured, supply and demand aligned and competition, attracted by high returns, reduced earnings. While profits and investment returns fell, free cash flow increased, as investment needs declined.

During the growth phase, the firm needed to raise money from equity and debt investors, who provided discipline and control of the firm’s activities. As it reached maturity, the firm could fund investments from its own free cash flow, reducing external scrutiny. This meant that managers paid off debt and retained surplus cash, increasing autonomy. All this increased the firm’s cost of capital and frequently led to poor investments.

Management overinvested in industries already suffering from over-capacity or, worse, invested in unrelated industries to diversify. Performance anxiety caused firms to overinvest in growth businesses to disguise poor returns from their mature businesses. Alternatively, firms under-invested in growth areas because of competitive pressures in their mature markets.

Jensen saw the conflict between the owner (shareholders) and the agent (the managers) in terms of control and utilization of cash flow. LBOs increased efficiency by reducing investments in unprofitable businesses, forcing the sale of individual assets or complete business units. Buyouts encouraged businesses to concentrate on identifiable and closely related activities, giving investors direct, undiluted exposure to specific businesses, pure plays. Investors had control over their portfolios, allowing better diversification and reducing the discount attached to a bundled investment. More debt forced firms to return cash to investors through increased interest and principal repayments, increased dividends, share repurchases, and capital returns. Higher debt reduced capital cost and lowered tax paid.

The key was the discipline of debt and active shareholders, such as private equity investors. The correct management incentives, usually substantial equity ownership by managers and payments linked to performance, were the cure-all for capitalism’s ills.

Drowning by Numbers

Jensen accurately identified the disease afflicting of American corporations. At RJR Nabisco the CEO’s dog flew on one of ten corporate jets under the name “G. Shepherd.” But Jensen identified the wrong cure. Private equity firms did not have the required operational skills to revitalize the companies they took over. Henry Kravis admitted: “We’re financial people, not operating people. We don’t know how to run a company. We’d only mess it up if we tried.”12

The aim became buy and flick. Rather than fix deep-seated problems, expensive managers used short-term measures to boost performance—cutting costs deeply and reducing investment. Then the business was sold or its shares offered to public investors allowing the private equity firm to sell out and cash in. Henry Kravis summed up the strategy: “Don’t congratulate me when we buy it. Congratulate me when I sell it.”13

There was little direct contact between the investors and the firms themselves. Austerity measures were delivered remotely via phone, fax, and emails. The emphasis was on the numbers, meeting financial targets to pay down debt. Corporate performance was analyzed and re-analyzed on spreadsheets that were becoming part of finance: “the personal computer accomplished for Wall Street buyout boutiques what the advent of gunpowder did for Mongol warriors.”14

Private equity firms controlled empires that were disparate in industry and geography, increasingly resembling the large companies that they dismembered. Michael Jensen found even this to be positive, comparing it to the keiretsu or zaibatsu structure in Japan where banks and financial institutions held equity stakes in companies they lent to. Unfortunately, as Edward Deming, the management expert, noted: “American management thinks that they can just copy from Japan—but they don’t know what to copy!”15

The success of LBOs relied on management incentives and privileged access to information. Managers, either existing or especially brought in, received 10–15 percent ownership in the purchased company, more generous than the 1–3 percent in stock options they would traditionally have received. A KKR associate accurately described the strategy: “Grab a man by his W-2 [the wage and tax statement used by the U.S. Internal Revenue Service to report wages] and his heart and mind will follow.”16

There were conflicts of interest in LBOs. Managers used privileged access to information about a company’s activities to lower the price, paving the way for a LBO that might benefit them. Where they were part of the LBO, existing management claimed to know how to fix or improve the business—but only if given a large equity interest. It was legal blackmail.

Buyout firms collected a fee, typically 1 percent of each purchase. In addition, the buyout firm charged an annual management fee, around 1–2 percent, on the investors’ funds, managed plus 20 percent carried interest, receiving a share of any investment gains on disposition. They charged annual monitoring and director’s fees. During negotiations, Gerald Saltarelli, chairman of Houdaille, argued that KKR should not be entitled to any fee for buying the company. Kohlberg argued he was entitled to a fee: “I’m an investment banker.”17

Lenders got high interest rates as well as substantial fees. When junk bonds started to be used for financing LBOs, Drexel Burnham Lambert (Drexel) received a fixed fee (0.50–1 percent) of the amount raised, a commitment fee, an underwriting fee, an advisory fee, warrants over the stock, and expenses. In the LBO of Triangle, Drexel earned fees of $25 million plus warrants over 16 percent of the purchased company. When banks lent to LBOs, they too were proficient at charging substantial fees. Legal fees, accounting charges, due diligence costs, and other professional fees routinely ran into tens of millions of dollars. Even the catering bill, for coffee, doughnuts and Chinese takeaways, ran into the tens of thousands.

Who was paying for this? The client. Where were the profits coming from? The massive leverage, substantial tax benefits, and “increased efficiency”—cost cutting primarily from reducing staffing levels and pay cuts for the rank and file employees. Magical debt was the stick—the sword of Damocles hanging over management forcing the right actions to be taken. There was the carrot—management would get very rich if they could meet targets.

Harvard Business School Professor Malcolm Salter referred to LBOs as “the repair shop for capitalism.”18 Finance had become the panacea for arresting America’s industrial decline. There was little attempt to address problems of product, manufacturing, quality, sales, and customer service. In Phillipe Meyer’s novel American Rust, a former employee of a U.S. steelworks who has been crippled in an industrial accident muses: “the Japs and Germans...were always investing...Penn Steel never invested a dime in its mills, guaranteed its own downfall...those welfare states, Germany and Sweden, they made plenty of steel...they were the ones supposed to go bankrupt.”19

Censored Loans

Believing they deserved a bigger share of the rewards, the insurers, who initially supplied the money for LBOs, demanded higher fees and more equity. Buyout firms turned to bankers and ultimately the junk bond market.

Bankers found the margin of safety on LBO loans low. But self-interest and large profits led to a change of heart. Bankers Trust (BT), in the process of transforming itself into an aggressive investment bank, recognized that the risk of LBO loans was manageable, interest rates and fees were high, the volume of business was substantial, and the buyout firms paid well. Others followed, and it became possible to raise large sums quickly.

In 1986, at a lavish dinner to celebrate the successful closing of an LBO, Don Kelly, the new CEO of Beatrice, a consumer products group, told the bankers: “This is the same group of dummies who lent me too much money before...guess what? You’ve gone and done it again!”20 The $6.2 billion Beatrice transaction resulted in fees to financiers and lawyers of $248 million, of which 53 banks shared $44 million.

Buyouts turned increasingly to junk bonds, the product of the mercurial Mike Milken and Drexel. Saul Fix, a KKR associate, summed it up: “Drexel’s money became a key element.... If we didn’t do it this way, we’d have to pay a lot more and have had to rely on a much more complex, unwieldy structure...we never would have been able to do all the things we did.”21

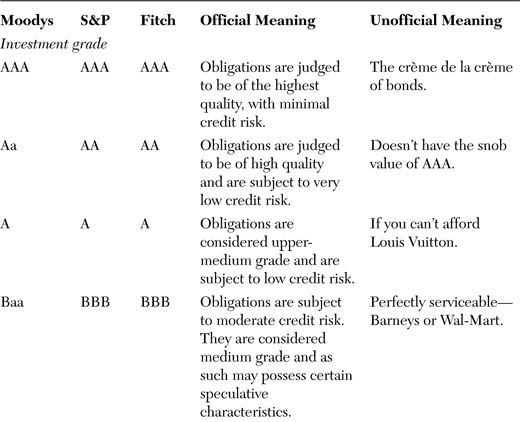

Bond markets traditionally provided finance only to highly creditworthy companies. Credit quality was a function of credit rating provided by the major rating agencies—Moody’s Investor Services (Moodys), Standard & Poor’s (S&P), and Fitch. The rating agencies were the equivalent of film censors. Instead of rating films for sex, violence, and offensiveness, they graded the credit quality of bonds. Table 9.2 shows the rating scale.

Insurance companies, pension funds, trust and endowment funds, banks, mutual funds, and the wealthy traditionally bought only investment grade bonds (rated BBB or better). Mike Milken and Drexel created an entire new market for noninvestment grade bonds, taking the use of debt and leverage on to a different plane. Meshulam Riklis, who controlled Rapid American, a conglomerate built with leverage, referred to it as the “effective nonuse of cash”22—at least, your own.

High Opportunity Bonds

In August 1985, Forbes argued that Milken had “created his own universe.”23 With great tenacity, an endless appetite for work, and a monomaniac focus, Milken was “an amazing salesman” of junk bonds.24 He disliked the term “junk,” preferring high opportunity bonds. They would eventually become high yield bonds.

At the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton Business School, Milken came across the work of W. Braddock Hickman. In his 1958 Corporate Bond Quality and Investor Experience, which sold 934 copies, Hickman’s laborious precomputer analysis showed that lower rated bond issues that paid high rates of interest to compensate for the higher risk were safer and had lower rates of default than previously thought. Even after factoring in losses when issuers defaulted, investors in low-rated bonds did better than investors in high-quality bonds. In 1984, New York University Professor Edward Altman confirmed the thesis.

Advocates now argued that junk bonds were a sound investment for investors with fiduciary responsibilities, as bond ratings overestimated the risk of noninvestment grade bonds. Numerous papers and books by independent analysts, who acted as consultants to, or were retained and paid by investment banks, extolled the case for junk bonds.

Analysis of defaulted bonds is tricky because there are few defaults, which are concentrated in specific industries (railways) or at specific times (severe recessions such as the 1920s). Markets and issuers change over time, and data is not comparable. Hickman did not conclude that ratings were incorrect but that there were errors, due to problems in forecasting the business cycle and industry developments. Lower-rated bonds outperformed at certain times of the economic cycle, mainly when markets became extremely concerned about default. It was an old investment adage—buy when everybody is selling, when there are blood and tanks on the street.

Altman’s studies compared defaults in one year to the entire universe of junk bonds. The rate of default in Year x was the number of defaults divided by the volume of junk bonds on issue. The rapid increase in the size of the market (from $10 billion outstanding in 1978 to $100 billion a decade later) lowered the default rates artificially. A fairer comparison was actual defaults as a percentage of the amount issued in the original year of issue.

Altman’s studies did not adjust for other games. Issuers routinely overfunded, raising excess cash, which meant borrowers would not default quickly. Financially distressed junk bonds were often exchanged for new securities, sometimes not paying interest in cash, to avoid default. No distinction was drawn between bonds issued by investment grade companies whose ratings had fallen and issuers who started as junk.25

In the late 1980s, as the LBO boom was ending, new research studies on junk bonds corrected the problems of previous studies. Paul Asquith, a professor at Harvard Graduate School of Business, with his colleagues David Mullins and Eric Wolf, found that junk bond default rates were higher than previously stated. Around 30 percent of all junk bonds issued in 1977–9 had defaulted or been subject to a distressed exchange. Lipper Analytical Services, an investment firm, found that over 10 years junk bonds provided lower returns than government bonds, earning the same as money market funds. Altman published new research reaching similar conclusions.26 As Laurence J. Peter, author of The Peter Principle, stated: “Facts are stubborn things, but statistics are more pliable.”

Fallen Angels

Milken put Hickman’s theories to work at Drexel Harriman Ripley, an investment bank that had once partnered with JP Morgan. As head of fixed income research and subsequently sales and trading, Milken operated in the bond underworld, buying and selling fallen angels or Chinese paper—bonds issued by investment-grade companies that had their ratings downgraded and were trading at deep discounts.

Milken’s trading made money but no friends. When Drexel traders who scorned junk bonds tried to shut down Milken, management pointed out that Milken made significant amounts of money using a modest amount of the firm’s capital. Investment-grade bond traders used more capital and made large losses. “Whom should I fire?” the manager asked.27

Unhappy that the firm restricted his trading by limiting his ability to take risks, Milken wanted to go back to Wharton to teach. His trading limit was increased from $500,000 to $2 million (a substantial sum at that time). Milken stayed, and in 1973 made $2 million in profits (a return of 100 percent on his capital) and received 35 percent of profits as a bonus. The percentage would stay the same throughout his career at Drexel, without any cap on the amount he could receive.

Milken’s success allowed him to expand, creating an autonomous unit with its own traders, sales staff, and research analysts to trade junk bonds. The unit sealed its independence by moving to Beverly Hills on the West Coast.

Junk People

Milken’s consistent mantra was that the rating of junk bonds was incorrect—the potential returns outweighed the risk. Investors in junk bonds received higher interest rates but also potential gains in the value of the bond if the company’s fortunes and rating improved. Buying lower-rated bonds was less risky because higher-rated companies were more likely to be downgraded—AAA-rated companies can only be downgraded. Buying a bond for, say, 40 cents per dollar of face value was less risky than buying a bond trading at a dollar (or par), as it could only fall. Milken argued that the debt holder rather than shareholder controlled the company. If a company missed any payment of interest or principal, the lenders could move in and take over.

Investors began to take notice, especially since high-rated bonds offered low returns and some, such as securities issued by the City of New York, defaulted on payment of interest. High returns from purchasing Milken’s junk bonds turned portfolio managers like David Solomon of First Investors Fund for Income into celebrities.

In 1974 Fred Carr, a former driveway repairman and manager of the Enterprise Fund in the 1960s, took over a small insurance company—First Executive Insurance. He created a product called the single premium deferred annuity (SPDA). The purchasers invested a fixed amount, and the insurance company contracted to pay them an agreed amount after a fixed period. The key to the SPDA was the interest rate—the higher the rate, the higher the final payout. Purchasing junk bonds to generate high rates, First Executive became the market leader in annuities, creating a large market for junk bonds.

Thrift institutions like saving and loans associations (S&Ls) traditionally made long-term mortgage loans on fixed rates, funding them with short-term deposits where the interest rates were adjustable. When newly deregulated short-term interest rates rose sharply, as Paul Volcker tried to tame inflation, the S&L’s cost of deposits exceeded the interest on loans. Congress changed regulations to help attract deposits and to improve profitability, expanding the S&L’s investment powers by allowing purchases of junk bonds. In the 1980s, mutual funds specializing in junk bonds allowed individuals to invest in the market. Attracted by media campaigns promoting high returns, investors flocked to the funds.

Buyers of insurance products and policies were inadvertently purchasing junk bonds. Repackaged as guaranteed investment contracts (GICs), issued by First Executive, junk bonds were being sold to pension funds. Depositors in S&Ls and the taxpayers guaranteeing the deposits were unwittingly exposed to junk bonds. Competitive pressures meant that the debate was not about buying junk bonds but why you weren’t buying them.

Milken’s Mobsters

But there just wasn’t enough Chinese paper to match investor demand—there were far too few fallen angels. When Goldman Sachs and Lehman Brothers issued the first junk bonds in 1977, Milken and Drexel seized the opportunity, starting with a $30 million issue for Texas International. Over time, they found new issuers of junk bonds—Milken’s mobsters.

Drexel forged relationships with the new robber barons—buyout firms, entrepreneurial outsiders like Turner Broadcasting, MCI, and McCaw Cellular, and aggressive corporate raiders like Carl Icahn and Boone Pickens. Drexel’s Christian Anderson summarized the situation: “There are only two kinds of companies—the comers and the goers. We finance the comers.”28 Observers later noted: “Pumped into buyouts, Milken’s junk bonds became a high-octane fuel that transformed the LBO industry from a Volkswagen Beetle into a monstrous drag race belching smoke and fire.”29

Harvard-trained Fred Joseph, Drexel president and CEO, wanted to build the firm to rival Goldman Sachs, then, as now, the benchmark for excellence. Lacking clients within the Fortune 500, Drexel’s investment banking franchise was built on the comers where expertise in junk bonds provided a crucial competitive edge. At a planning session, more psychotherapy than business school, Cavas Gobhai, an Indian consultant, saw the strategy as: “Merge with Mike.”30

Drexel adopted aggressive and unconventional tactics, backing hostile acquisitions. Traditionally, companies lined up bank loans to support bids. Milken evolved the highly confident letter, which stated that Drexel was “highly confident” that it could obtain the necessary financing. Originally nicknamed the Air Fund, the highly confident letter lacked legal status, relying on Milken and Drexel’s ability to underwrite and place bonds to raise the money. Drexel’s reputation meant that the letter was as good as cash.

Modestly resourced corporate raiders, backed by a highly confident letter, were suddenly credible. Jay Higgins, head of mergers and acquisitions at rival Salomon Brothers, observed: “Big companies used to worry only about threats from other big companies. But with Drexel doing the financing, anybody long on ideas and short on capital is a threat.”31 Drexel moved from providing advice to bankrolling transactions as a principal.

The raiders, leveraged buyout funds, and investors met at the annual Drexel’s High Yield Bond Conference to raise money for new deals. Held at the Beverly Hills Hotel, owned by Ivan Boesky, an investor specializing in risk arbitrage (betting on outcomes of mergers and acquisitions), the Predator’s Ball was the bacchanalian centrepiece of the world of hostile takeovers and debt.

Milken always opened the conference with a simple statement: “There’s $3 trillion in this room.” Each year the number was higher, providing a measure of the power and influence of the players and Drexel. At the 1986 conference, Drexel screened a video (an annual tradition) showing a businessman striding into a meeting in a boardroom of The Fat and Lazy Corporation, brandishing a Drexel titanium card with a credit limit of $10 billion. After scrutinizing the card carefully, the Chairman makes an imprint of the card as the executives strap on gold-colored parachutes and jump out the windows. The businessman, played by Larry Hagman (then enjoying success as the tyrannical and ruthless J.R. Ewing in the hit TV series Dallas), grins and tells the audience: “Don’t go hunting without it.”

The Sweet Envy of Bankers

Nick Brady, CEO of the investment bank Dillon Read, saw Drexel as “junk people buying junk bonds.”32 Michel Bergerac, chairman and CEO of Revlon, subject to a hostile bid from Ronald Perelman, sneered: “Drexel has inserted itself between the pawnbrokers and the banks.”33

Drexel’s business practices failed modern tests of corporate conduct. One attendee naïvely misunderstood the presence of extremely attractive women at the firm’s functions: “I’ve got to hand it to these guys—I’ve never seen so many beautiful wives.” A banker observing one guest conversing at length with a woman, set him straight: “Tell Irwin he doesn’t have to work so hard. She’s already paid for.”34 When Perelman, a Drexel client, sought entry into the Ivy League social circle after completing the takeover of Revlon, one observer noted: “This has got to be the highest price ever paid in the history of this country to get a good table at a New York restaurant.”35

But Drexel rapidly became the most profitable investment bank on the street, using its profits from junk bonds to diversify its clients and businesses. It was on its way to its objective: “to be as big as Salomon [Brothers] so we can be as arrogant as they are and tell them to go stuff it.”36 Drexel now pitched to corporate blue bloods with an approach straight out of The Godfather: You become our clients and pay us; we will protect you. Clients shopped around, moving from “the traditional concept of marriage to one-night stands.”37

Other banks eyed Drexel’s business enviously but feared that a déclassé activity like junk bonds would alienate traditional clients. By 1983/4, major investment banks caved in. Morgan Stanley, the bluest of the blue bloods, advised companies to take on debt, initiated hostile takeovers, and traded junk to protect its franchise. Eric Gleacher, Morgan Stanley’s head of mergers and acquisitions, defended the strategy: “When you look at the debt of the world, the debt of the country, and the debt of the private sector, you can’t with a straight face tell me that a few speculative merger deals are going to tip the balance and create disaster.”38

Competition on fees and commissions was ferocious. Traditional syndicates formed by investment banks to market securities were redundant. Drexel frequently underwrote bond issues alone, relying on its capability to underwrite large amounts at short notice, risking its own money and trusting its placement power.

Drexel excelled in the age of trading and risk: “Sharp elbows and a working knowledge of spreadsheets suddenly counted more than a nose for sherry or membership in Skull and Bones [a secret society at Yale University].”39 Lazard Freres’ Felix Rohatyn, a veteran investment banker, did not see the changes positively: “A cancer has been spreading in our industry...Too much money is coming together with too many young people who have little or no institutional memory, or sense of tradition, and who are under enormous economic pressure to perform in the glare of Hollywood like publicity.”40

In the 1980s, when Merrill Lynch was rumored to be merging with Drexel, the betting on the new combine’s name was Burn’em & Lynch’em. The merger did not happen. A quarter of a century later, Merrill would be destroyed by a different kind of junk.

Thank You for Borrowing

Throughout the 1980s, money flowed into buyout funds floated by LBO firms. The cost of debt fell and availability increased. Purchasers paid higher prices for businesses because the availability of cheap debt made the purchase more expensive. As the margin of safety fell, buyers and the investors took on more risk.

Subordinated (“sub” or “junior”) debt replaced equity. If the company went bankrupt, then the subordinated debt holders would be paid after the senior debt. Subordinated debt investors received higher interest rates, but the cost to the borrower was lower than equity. Zero coupon debt allowed interest to be accrued every year with payment deferred till maturity. Pay-in-kind (PIK) notes allowed the company to pay interest in new IOUs not cash. Exchangeable variable rate debentures, with low interest rates that would reset at a future date, anticipated adjusted rate subprime mortgages (ARMs). Scarce cash was stretched further to service the increasing debt. The day of reckoning—when the debt and the interest would have to be paid—was postponed.

In November 1984, Drexel arranged a $1.3 billion bond refinancing the debt of Metromedia Broadcasting Corporation, which had been bought in a LBO by John Kluge, chairman of Metromedia, and three managers. The complex package reduced Metromedia’s cash outgoings, helping Kluge to avoid selling broadcasting assets to meet loan conditions. Interest rates went up from around 14.90 percent per annum to 15.40 percent per annum, but cash interest payments fell from 14.90 percent per annum to 10.30 percent per annum for the first 5 years. Around $290 million in principal repayments were deferred for 4 years.

Critics predicted problems with the arrangements. In May 1985, Rupert Murdoch bought Metromedia’s TV stations for $2 billion ($650 million in cash and $1.35 billion in assumed debt) to create the Fox Network. Kluge netted $3 billion profit from the transactions. The critics were silenced.

The ambitious 1989 RJR Nabisco deal marked the high-water mark of the boom. RJ Reynolds was a tobacco business that owned the iconic Camel brand. RJR’s stable businesses, low debt levels and low investment needs made the firm an attractive LBO candidate. Ross Johnson, the CEO, put RJR into play when he joined with Shearson Lehman Hutton to take the company private. The board refused the initial offer of $75 per share, initiating an auction. KKR eventually prevailed at a price of $109 per share, valuing RJR at $31 billion. The purchasers put in around $1.5 billion in equity, leaving the remaining $29.5 billion to be financed with debt.

One Bridge Too Far

But the environment was changing. Political concerns about jobs, investment security, and the large profits from LBOs led to congressional inquiries. Fred Hartley, chairman of Unocal, which was subject to a hostile bid from Boone Pickens, told the U.S. Senate:

Corporate raiders and bust up takeovers have not inspired one new technological innovation; they have drained off investment capital. They have not strengthened companies; they have weakened them, loading surviving firms with onerous debt.41

Alan Greenspan was equivocal, arguing that “the trend towards more ownership by managers and tighter control...enhanced operational efficiency” while cautioning that increased debt created “broad based risk.”42

Susan Faludi’s Pulitzer-winning 1990 Wall Street Journal story “The reckoning” was an exposé of KKR’s LBO of Safeway Stores, purchased for $4.7 billion, of which 94 percent was borrowed. Faludi drew attention to shareholder greed and the costs borne by employees of the company and the community. It did not help that KKR completed a successful public offering of 10 percent of Safeway at 450 percent of what they had paid 4 years earlier.

Barbarians at the Gate told of mismanagement, financier greed, and ignored social costs in the buyout of RJR. Michael Jensen complained that the book ignored “clear evidence of corporate wide inefficiencies at RJR Nabisco, including massive waste of ‘corporate free cash flow.’”43

Unmanageable debt levels, over-optimistic forecasts and falling asset values after the 1987 stock market crash led to the bankruptcy of the Federated Department Stores, Revco drug stores, Walter Industries, FEB Trucking, and Eaton Leonard LBOs. Mounting losses to lenders in LBOs reduced the availability of finance. Changes in regulation made it more difficult for S&Ls and insurance companies to hold junk bonds. As they sold, prices fell, forcing other holders to follow and causing the junk bond market to seize up.

To compete against Drexel’s highly confident letter, other banks and securities firms had provided bridge financing, using their own money to bridge the client from the time of making the offer to actual payment. When the bank and junk bond markets closed, it proved a bridge too far. The banks that expected to refinance the bridge loans later found themselves stuck with loans.

Drexel found itself tangled in a web of allegations and investigations into insider trading. In 1986, Dennis Levine, a Drexel investment banker, was charged with insider trading. Drexel traders joked: “Anybody who had to do 54 trades to make $12 million couldn’t be any good.”44 Levine implicated Ivan Boesky, the model for Gordon Gekko in the 1987 movie Wall Street. In 1986, Boesky had declared: “Greed is all right...greed is healthy. You can be greedy and still feel good about yourself.”45 Boesky saved himself by cooperating with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and informing on Milken.

The SEC and Rudy Giuliani, the U.S. attorney for the Southern District of New York, launched wide-ranging investigations into Drexel’s operations. The SEC brought charges of insider trading, stock manipulation, defrauding its clients, and stock parking (buying stocks for the benefit of another) against Drexel and Milken. Giuliani threatened indictment under the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (RICO) Act, originally intended for use against organized crime. Drexel could be required to post a performance bond of as much as $1 billion or have its assets frozen. Under an agreement with the government, Drexel pleaded nolo contendere (no contest) to six felonies and paid a record fine of $650 million. In March 1989, Milken was indicted and left the firm. In February 1990, Drexel filed for bankruptcy.

National Treasure

The Wall Street Journal stated:

Not since J.P. Morgan has any financier influenced Wall Street and the nation the way Michael Milken has.... Not surprisingly, Mr. Milken, 42, aroused the fear and loathing of industrialists whose companies fell to his onslaughts or seemed likely candidates for his attention.

He was “the most important financier of the century.”46 In its August 1985 article, Forbes considered that Milken “isn’t just a step ahead of his Wall Street peers—he’s a quantum leap ahead, acting as venture capitalist, investment banker, trader, investor.”47

Milken’s activities entailed inherent conflicts of interest. Clients were encouraged to overfund—raise more money than required—with the surplus funds being invested in junk bonds sold by Drexel. The firm financed insurance companies and the purchase of S&Ls that then invested in junk bonds. Drexel financed acquisitions with junk bonds placed with Milken’s clients. After completion of LBOs, the company’s pension fund purchased high-yielding GICs from First Executive, creating demand for junk bonds. The higher return allowed the pension fund to reduce required contributions from the sponsor or even allow any overfunding to be returned. The money flowed back to the corporate raiders and investors, fueling a new round of acquisition activity. Relentless churn, buying and selling bonds, increased earnings.

Drexel traded with and raised money for risk arbitragers, like Boesky who bet on stocks in play in mergers and acquisitions. Bank Chinese walls were meant to separate the flow of material between those that make investment and trading decisions and others privy to undisclosed material information that may influence those decisions. In April 1986, Milken, contemptuous in his disregard for such niceties, told investors that “buying high-yield securities has overpowered all regulation.”48

In the Drexel system, each division received bonuses linked only to individual performance, creating acrimonious relationships between the immensely profitable high-yield department and other parts of the firm. In 1986, Drexel earned $545.5 million, then the largest profit ever for a Wall Street investment bank. In 1987, Milken earned $550 million. Milken organized limited partnerships that allowed him and selected employees to invest in Drexel deals. The partnerships frequently bought and sold junk bonds or ended up with options to buy shares in buyouts that made more money than Drexel on some deals.

Milken’s genius was to develop a system providing financing, arranging acquisitions, and trading in bonds and shares that excluded other players. He controlled information on companies and who held specific bonds or shares, setting up purchases and sales of securities at prices that he set. Anybody who wanted to play had to involve Drexel and Milken. For a brief period of financial time, Milken was the market—a financial “god.”

In April 1990, Milken pleaded guilty to six securities and reporting felonies but did not admit to insider trading. He paid $200 million in fines and a further $400 million to shareholders hurt by his actions. Accepting a lifetime ban from the securities industry, Milken served 22 months (from March 1991 until January 1993) of a 10-year prison sentence. Milken’s fans argued that he was a scapegoat, brought down by the American WASP business establishment because he was Jewish.

Today Milken is worth more $2 billion and active via the Milken Foundation and Milken Institute. In November 2004, Fortune magazine called Milken “The man who changed medicine” for funding medical research into life-threatening diseases. On May 1, 1990 The New York Times provided an assessment: “Michael Milken is a convicted felon. But he is also a financial genius.”

Even without Milken, the junk bond market would recover and reemerge. Debt and leverage would become part of the mainstream. The ingredients of Drexel’s success, especially the emphasis on trading and using the bank’s own capital, would become the rulebook for others.