11. Dice with Debt

In 2009, London’s Daily Mirror found the culprit responsible for the financial crisis—David Bowie, aka Ziggy Stardust and the Thin White Duke. In 1997, he issued $55 million of 7.9 percent per annum 10-year Bowie Bonds backed by future royalties from 25 albums containing 287 songs, including Space Oddity, Starman, Jean Genie, Fame, Young American, Ashes to Ashes, Let’s Dance, China Girl, and Modern Love. Bowie gave up 10 years’ worth of royalties in return for $55 million up front.

Although the Bowie Bond pioneered the securitization of intellectual property rights, the technique itself had been used since the 1970s to repackage loans, especially mortgages, into securities sold to investors. Michael Milken called it “democratization of capital.”

In the Japanese TV cooking show Ryōri no Tetsujin, literally “Ironmen of Cooking” (the American version is called The Iron Chef), chefs battled against each other to create dishes around a specific theme ingredient. Over time, bankers learned to cut and dice debt in more ways than any celebrity television chef. Securitization was a bacchanalian feast of unprecedented size for bankers and their acolytes.

Securitization Recipes

Securitization is a recipe for cutting and dicing debt into more debt. Like food recipes, securitization ranges from simple dishes to haute cuisine. The only ingredient is debt—mortgage loans, credit card loans, car loans, loans to companies, loans to people, loans to people who cannot pay, any loans at all. Poor quality loans are no barrier to an acceptable and edible final securitized product.

Haute securitized debt depends on various condiments—SPVs, derivatives, bonds, tranches, over-collateralization, and excess spreads. Kitchen staff is needed—bankers and brokers to make loans; traders to structure the deal, price and hedge it; sales people; rating agencies to bless the deals as fit for investor consumption; servicers to monitor things; accountants to track the money; trustees to look after bondholders’ interests; lawyers to protect everybody, especially themselves. Securitization was a bacchanalian feast of unprecedented size for bankers and their acolytes.

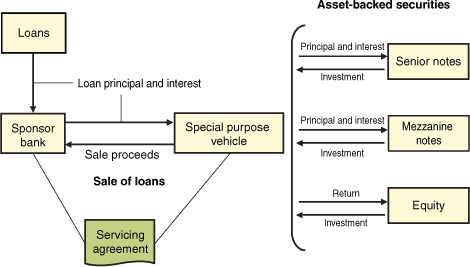

The structure is set out in Figure 11.1. Lenders sell loans they made to an SPV, not associated with the seller. The SPV, a trust or a company located in the tax-efficient balmy Cayman Islands, pays the lender for the purchase from the proceeds of bonds it issues to investors, asset-backed securities (ABSs). ABS investors, indirectly via the SPV, own the loans, relying on the cash flows from the underlying loans for the interest and principal they are entitled to receive.

Figure 11.1. Asset-backed security structure

When sold to the SPV, the original loans and any associated borrowing disappear from the balance sheet of the original lender. As the loans are sold off, the lender can make new loans, freeing the lending institution from constraints of capital and funding resources. Lenders also raise long-term funds matching the life of loans and so reducing risk. For a poor-credit-quality lender, the cost of money is lower, as the ABS investors look through to the underlying loans as collateral. Lenders transfer the risk of loss on their loans. If the borrowers on the underlying loans do not make their contracted payments, then the ABS investors would suffer losses. In return for assuming this risk, investors earn higher rates of return than on comparable bonds. Initially, the risk of loss was low as securitization used high-quality mortgage loans to modest folk, carrying a government or near-government guarantee.

Slice and Dice

Lewis Ranieri of Salomon Brothers and Lawrence Fink (then at First Boston and subsequent founder of Blackrock, an investment manager) pioneered the structure. In 2004, BusinessWeek honored “Lew,” immortalized in Michael Lewis’ Liar’s Poker, as one of the great innovators of the past 75 years. In March 2008, Nobel-prize-winning economist Robert Mundell included Ranieri in his list of the “Five goats who contributed to the financial crisis of 2008,” together with President Bill Clinton, former AIG head Hank Greenberg, Ben Bernanke, and Henry Paulson.1

The key to securitization is the allocation of risks between different investors. Quantitative analysts segmented mortgage cash flow from a complex menu of choices, manufacturing investment dishes to meet investors’ appetites.

U.S. mortgages are generally 30 years and fixed rate. Minimal prepayment penalties mean that if interest rates fall, then mortgagors pay back their old mortgages, refinancing at lower rates to reduce their repayments. ABS investors risk early return of their money, which must be reinvested at lower rates. CMOs (collateralized mortgage obligation) segmented cash horizontally, creating different bonds out of a pool of standard mortgages to reduce prepayment risk.

If there are four separate bonds, the first class receives prepayments before the other classes, getting repaid earlier. The first class receives a lower interest rate reflecting lower risk. The second class receives payments next and so on. The Z tranche, at the bottom, receives the highest return but does not receive any payment until all other tranches are fully paid off. CMOs allow 30-year mortgages to be converted into bonds with different, theoretically more predictable maturities to match investor needs.

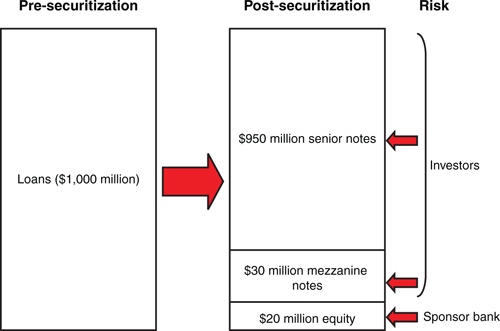

Vertical segmentation, tranching (French for slicing) improved credit quality (see Figure 11.2). The SPV issues three different classes of securities. The most risky security is the equity tranche, which takes first losses on the underlying loans. The next most risky security is the mezzanine notes, which bear losses only if the losses exceed the amount of the equity tranche. The least risky security is the senior tranche, which only bears losses if the losses exceed the combined value of the equity and mezzanine tranches.

Figure 11.2. Asset-backed security tranches

Assume an underlying portfolio of $1,000 million made up of 5,000 mortgages of $200,000 each. Assume that the SPV issues $20 million in equity, $30 million in mezzanine notes, and $950 million in senior notes to finance this portfolio. If a homeowner defaults, then the lender loses 50 percent of the amount lent ($100,000 being 50 percent of $200,000). The loss is lower than the amount of the loan because the property can be sold to recover part of the amount lent, a recovery rate of 50 percent.

Defaults on 200 mortgages (4 percent) wipes out the equity tranche (loss of $100,000 per loan times 200) but investors in mezzanine and senior notes receive their investment back in full. If 10 percent of the mortgages default, then the loss of $50 million (loss of $100,000 times 500) wipes out the equity and mezzanine. If the entire portfolio defaults, senior note holders get back $500 million ($1,000 million minus losses of $500 million—calculated as loss of $100,000 times 5,000)—a loss of 53 percent ($500 million loss divided by $950 million face value). Only if all mortgages defaulted and all the underlying houses were worthless would the senior note holders lose their entire investment.

Betting on no or very few defaults, equity holders take the greatest risk and receive the highest return. Senior note holders take the least risk and receive low returns. Mezzanine is in the middle—less risky than equity, more risky than senior, betting on modest losses not exceeding the equity tranche (less than 4 percent of mortgages). Mezzanine note holders receive higher returns than senior note investors but less than equity.

The assumption is that the entire underlying portfolio is unlikely to default simultaneously. If the equity and mezzanine notes provide a sufficient buffer, then the risk of loss on the senior notes is reduced. The risk of individual notes can be adjusted similarly by changing the subordination level—the size of the tranches that take earlier losses.

If the average historical default rate on the mortgages is 0.5 percent, then the expected loss would be $2.5 million (0.5 percent of 5,000 mortgages times $100,000 loss per mortgage). As there would have to be 20 times the average loss ($50 million divided by $2.5 million) before they would lose, the senior notes are considered to carry very low risk, receiving the highest credit rating (AAA). The mezzanine note holders are a relatively low risk and may command an investment grade rating, as losses of eight times average loss are required for them to lose money.

Conservative investors invested in low risk AAA or AA-rated securities, preferring the return of capital to the return on their capital. Alchemy transformed portfolios of low quality and junk loans to highly rated securities, allowing investors to purchase them in the form of highly rated debt ABSs. Investors with greater risk appetite purchased mezzanine notes or the equity tranches. Investors in the equity, known as toxic waste, earned high returns as long as losses were zero or low. In most deals, the bank selling off the loans or arranging the securitisation took at least a part of the equity tranche to provide comfort to other investors—this was the bank’s skin in the game or hurt money.

Tranching is like buying a place to live in a flood-prone area. To protect yourself from the one-in-10,000-year flood, you buy an apartment in a tower above previous known flood levels, with a large margin of safety. You pay more for your flood-safe penthouse while buyers of the lower levels trade off the lower price against the “remote” risk of the flood.

In drought years, everybody lives happily. When the flood comes, the owners of the lower levels are flooded. You congratulate yourself on your perspicacious decision, only to find that the floods damage the foundations of your tower block, weakening the structure. The utilities and services don’t function. You cannot get to and from your penthouse. You cannot offload the penthouse to anybody at any price. If you miscalculated the margin of safety of the one-in-10,000-year flood, then you require full scuba gear to sit in your living room contemplating the alchemy of tranching.

Almost as Safe as Houses

Like Henry Ford, bankers are good at mass production, quickly adopting and developing a successful product. The capability to repackage all kinds of debt into highly rated securities that investors sought allowed the expansion of debt levels to reach epic proportions.

The early focus in the United States was on MBSs (mortgage backed securities)—repackaging and selling off mortgages guaranteed by government-sponsored entities. As securitization became accepted, bankers adapted the technique to pools of private mortgages, automobiles (CARS—certificate for automobile receivables) and credit card debt. In the late 1980s, Milken created CBOs (collateralized bond obligations) and CLOs (collateralized loan obligations), repackaging corporate debt. Soon, corporate loans, private equity loans, loans secured by commercial real estate, and emerging market junk bonds were all being securitized.

A bank making a loan to a company was required by regulators originally to hold capital of 8 percent ($8 for every $100 loan) against risk of loss. If the bank charged a margin of 1 percent per annum, then the return on capital was 12.5 percent per annum (1 percent divided by 8 percent), usually below the bank’s cost of capital determined by the CAPM (capital asset pricing model). Loans to high-quality companies paying low margins were now pooled and sold off as CLOs. Assuming that the 2 percent equity tranche was retained by the lending bank and the CLO cost was 0.2 percent per annum (reducing the loan margin from 1 percent to 0.8 percent), this tripled the return on capital to 40 percent per annum (0.8 percent divided by 2 percent).

As banks held the equity and the likelihood of losses exceeding the equity tranche was low, the return on capital increased but the risks were unchanged. As executive compensation and stock prices were linked to return on capital, banks used securitization to boost returns.

Mirroring Anthony Trollope’s 1867 novel Last Chronicle of Barset, whose characters invest in mortgages, investors purchased MBSs as low risk and secure investments paying regular income. The higher return available on securitized bonds relative to ordinary securities of similar quality was attractive.

Synthetic Stuff

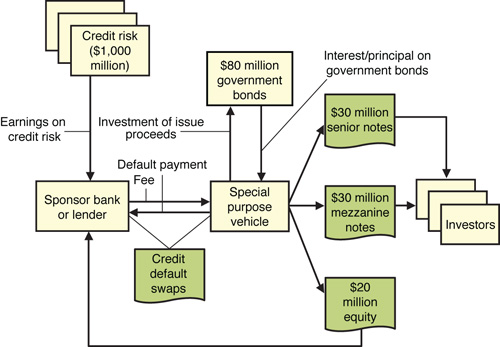

In the 1990s, securitization underwent a makeover, being rebranded CDOs (collateralized debt obligations), a term subsuming various types of underlying loans and securitization formats. In 1997 JP Morgan introduced synthetic securitization, overcoming the unwieldy need to transfer the underlying loans to the SPV and also lowering the cost of transferring the risk. Instead of selling the loans, the lender now purchased credit insurance against the risk of loss using a credit default swap (CDS).

The structure is shown in Figure 11.3. The bank purchased separate credit insurance policies from the SPV on each loan it wanted to transfer. As in a traditional ABS structure, the SPV issued securities. Instead of issuing securities equal to the face value of the loans insured, they issued a smaller amount—$80 million against an underlying portfolio of $1,000 million. The proceeds of the bonds were used to buy government bonds, such as U.S. Treasury bonds. These bonds were then pledged to secure the SPV’s payment obligations under the credit insurance policies it had sold to the bank.

Figure 11.3. Synthetic CDO

Over the life of the deal, the bank paid insurance premiums to the SPV, which together with income from the government bonds financed the interest payments to the investors in the senior and mezzanine notes, with anything left over going to equity. If there are no defaults on the underlying loans, then at maturity of the structure the bondholders get paid from the proceeds of the maturing government bonds. If there are defaults, then the bank’s claims under its insurance policies are paid out of the government bonds, reducing the amount available to equity holders, mezzanine note holders, and finally senior note holder (in that order). The structure of risk in the synthetic CDO is shown in Figure 11.4.

Figure 11.4. Synthetic CDO Tranches

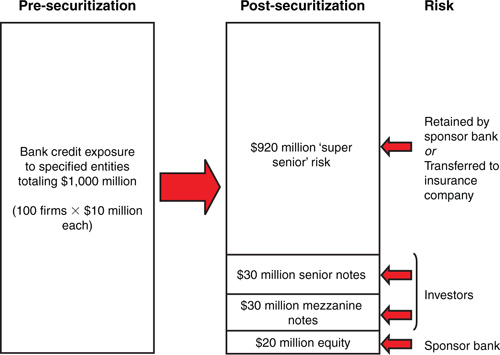

Assume an underlying portfolio of $1,000 million made up of 100 loans of $10 million each to companies. Assume that the SPV issues $20 million in equity, $30 million in mezzanine notes and $30 million in senior notes. The SPV issues only $80 million of securities in total, while assuming the risk of a $1,000 million portfolio of loans. This leaves $920 million unhedged, which, as described below, remains with the bank.

Assume the lender will lose 60 percent of the amount loaned ($6,000,000) if any borrower defaults, a recovery rate of 40 percent.2 Three loan defaults (3 percent of the loans) or losses of $20 million (loss of $6,000,000 per loan times 3) wipe out the equity tranche entirely. Eight defaults (8 percent of the loans) or losses of $50 million (loss of $6,000,000 times 8) wipes out the equity and the mezzanine. If losses are more than $50 million, then the senior note investors suffer losses. Thirteen defaults (13 percent of the loans) or losses of $80 million (loss of $6,000,000 times 13) wipe out the equity, mezzanine, and the senior note investors.

After 13 defaults or losses of $80 million, the SPV has no more money to cover additional defaults under the insurance policies it has entered into with the bank. The risk on the remaining $920 million (92 percent of the portfolio), known as the super senior tranche, reverts to the bank and is retained or must be transferred to another party. Given that losses would have to be very high relative to the risk of the loans and the AAA-rated senior tranche wiped out entirely, the super senior tranche is as close to risk free as possible. Regulators agreed, minimizing the capital that banks have to hold against the super senior risk.

Where the bank does not pay a third party to assume the super senior risk, the cost of securitization falls from around 0.2–0.3 percent per annum to around 0.05 percent per annum. Even if the super senior risk had to be transferred to a third party, the cost of around 0.1 percent per annum was lower than what bond investors required for AAA-rated bonds in a normal securitisation, so reducing the cost.

This residual risk of catastrophically large losses could be transferred using a super senior CDS (an insurance contract) to reinsurance companies (AIG, Swiss Re, Gen Re) and monolines or bond insurers (MBIA, Ambac). Large reinsurers, like AIG, were looking for insurance-type business that diversified traditional risks. Monolines’ traditional business of insuring municipal bonds was declining. Local municipalities now obtained credit ratings directly or could access financing without the monoline guarantee (known as the bond wrap). Synthetic securitizations, where risk was packaged into insurance-like contracts, were ideal for these investors.

A synthetic securitization has high levels of leverage, as only $80 million of money supports $1,000 million of credit risk. Even where the super senior risk was hedged with a third party, the counterparty did not have to put up money initially, increasing leverage and risk. In traditional securitization, the underlying loans existed. In synthetic securitization, the bank could buy insurance without owning the underlying loan, allowing shorting of credit risk to profit from a decline in the credit quality or default of the named entity. There was no theoretical limit on the volume of securitizations that could be completed. Volumes became detached from the underlying loan and debt markets.

If private equity and junk bonds increased reliance on leverage and appetite for different instruments, then securitization took the availability of debt to an entirely new level.

Regulators loved the theoretical idea of breaking risk into tiny particles, distributing it widely. In practice, risk was spreading like a virulent virus through the financial system, ending up in unknown places in the hands of investors, who did not understand the complex risks that they assumed. As Iceland imploded during the financial crisis, traders speculated that the Icelandic banks’ fatal dalliance with structured finance was simply confusion between the word c-o-d (an area of Icelandic expertise) and the non-piscine c-d-o (collateralized debt obligations).

Get Copula-ed

Assorted statisticians, mathematicians, scientists, and MBAs with little knowledge of banking now shaped packages of loans into complicated objets d’art. They built simplified models to predict patterns of cash flows from the underlying loans. In the ultra-rational world of efficient markets, prepayments were assumed to be linked to interest rates adjusted for behavioral nuances. Historical data was used to estimate the risk of nonpayment (default rates) and the loss rate (the amount lent minus the recovery rate). Historical data was used to estimate default correlation, the risk that if one loan defaulted, then other loans might also default.

Statistical analysis works moderately well with mortgages, at least simple traditional residential mortgages. Performance of large numbers of loans approximates an average. Individual calamities, lost jobs, illness, fraud, do not affect the pool significantly, as most borrowers make their payments as required. The risk of all homeowners defaulting at the same time is low.

In corporate loan securitizations, the models were more problematic. There were perhaps only 100 corporate loans compared to 5,000 mortgages for the same size portfolio, making individual defaults and loss more significant. Investment grade companies also default infrequently and their recovery rates fluctuate. Correlation between defaults is complex. If a major customer defaults without paying for goods and services supplied then the firm is more likely to default. If a competitor defaults, then the firm’s default risk may decrease if it picks up business, or increase if it is affected by the same problems that caused the default.

In his paper “On default correlation: a copula function approach,” David Xiang Lin Li, a Chinese-born actuary, used a Gaussian copula to determine whether two companies will simultaneously default (joint default probability).3 Gaussian refers to the assumption of a normal bell-shaped distribution. Copula in Latin means “combining.”

The idea drew on changes in life expectancy when a spouse dies. In general, in the year following a loved one’s death, women and men are, respectively, more than twice and six times as likely to die than normal. Actuaries used statistical techniques to model stress cardiomyopathy or apical ballooning syndrome, dying of a broken heart. Li applied this approach to the likelihood of default in a portfolio of loans.

The model’s attraction was its simplicity and ease of application. Bankers and quants could get deals done. But the simple model could not capture the complex relationship between two loans. The expected default correlation could not be objectively calculated, only extrapolated from other information, like share prices or credit margins. Small changes in input changed the results significantly. Uncomfortable with his model, in 2005, Li told The Wall Street Journal: “Very few people understand the essence of the model.” In 2006, Janet Tavakoli, a former derivative banker, reflected: “Correlation trading has spread through the psyche of the financial markets like a highly infectious thought virus.”4

Sticky Mess

Massive investment in quantitative infrastructure to structure, trade and sell ABSs, created a relentless drive for revenue, a constant push for deals and innovation. If the returns were sufficient, any assets could be repackaged and sold to investors. Securitization of life insurance policies (death bonds), hurricane, and earthquake risk (catastrophe or cat bonds) emerged. MBS structures reached levels of complexity, requiring color-coded risk warnings originally used on ski runs.

Innovation improved tranching. Excess spread accounts lowered the equity and mezzanine debt required to reach a target rating, allowing sponsors with less capital to complete securitizations. Prepayment tranching, sequential tranching, and parallel tranching improved the predictability of the life of the bonds. Investors could choose between PAC (planned amortization class) bonds, TAC (target amortization class) bonds, VADM (very accurately defined maturity) bonds, and the sticky jump Z tranche. A 2008 conference agenda posed the question: “Should the taxpayers be concerned that the Fed accepts private label whole loan nonsticky jump Z-tranche CMOs as collateral when the casino doesn’t?”5

In 1987, Howard Rubin, a Merrill Lynch trader, lost $377 million in mortgage trading. MBSs are split into IO (interest only) and PO (principal only) bonds. IOs pay out only the interest payments on the underlying pool of mortgages. Lower rates mean more prepayments, meaning less interest payments reducing the price of the IOs. Higher interest rates mean lower prepayments and more interest payments, increasing the value of the IOs. POs pay only principal, effectively like zero coupon bonds where you paid $800 for a bond that at maturity pays $1,000. POs behave exactly the opposite to IOs. If interest rates go down, then they appreciate in value, as the investor receives the face value of the bond earlier because of higher prepayments. If interest rates go up, then POs decrease in value as you get paid back later. Rubin owned a large amount of POs from Merrill Lynch’s deals that the firm had not managed to sell. When interest rates went up, he made large losses and tried to make them back by buying more POs.

Merrill Lynch had no “eye deer” that Rubin had taken on so much risk. Old-fashioned stockbrokers with minimal understanding of risk and complex financial products, William Schreyer and Dan Tully, the heads of Merrill Lynch, announced that “the ship will sail closer to shore.”6 Rubin was fired but went on to a successful career at Bear Stearns. Ace Greenberg, the head of Bear Stearns, believed in “second chances” and thought Rubin “can make a real contribution.”

Merrill tended to be in the thick of trouble and calamity. In 1994, Merrill was involved in the Orange County derivative losses. In 2001, when the Internet bubble burst, Merrill was there front and center. The pattern would repeat with CDO investments in 2008 under Stan O’Neal.

In 1987 a trade journal warned: “For Wall Street in general, Merrill’s loss is a reminder of the dangers of financial engineering.... The pace of innovation has been breathtaking. Unfortunately, the growth in understanding has been less impressive.”7 No one understood what economic commentator James Grant stated: “Financial engineering is the science of structuring cash flows...credit analysis is the art of getting paid.”8 Risk would return over and over via new structures, each time bigger and more toxic than the last.

Several Houses of One’s Own

To write fiction, according to English writer Virginia Woolf, a woman in Victorian England needed money and a room of her own. In modern America, everyone needed a large house and increasingly several houses. Money was not strictly needed, as rising house prices provided the necessary cash. The houses, the loans to finance them, and the securitized bonds based on the mortgages were classics of literary fiction.

Houses provide shelter, a dwelling place. In a hostile world, houses became self-sufficient fortresses with diversions (TV rooms and home entertainment centers), nature (gardens), recreation (home gyms) and oceans (swimming pools). You never had to leave, reflecting philosopher Søren Kierkegaard’s observation: “robbers and the elite agree on just one thing—living in hiding.”9

The average U.S. home more than doubled in size—from 1,000 square feet (93 square meters) in 1950 to 2,400 square feet (223 square meters) by the early 2000s. Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen built a 74,000-square-foot (6,882-square-meters) house, roughly the same size as the Cornell Business School where 100 people worked. Virginia Woolf would have recognized the MacMansions: “Those comfortably padded lunatic asylums which are known, euphemistically, as the stately homes of England.”

As governments subsidized home ownership, believing it created a more stable society, home ownership ceased to be the preserve of the wealthy. In the UK Margaret Thatcher sold public housing to tenants at a discount. Governments provided subsidies, tax deductions on mortgage-interest payments, or lower taxes on capital gains from the sale of a residence.

The concept of home ownership was enthusiastically adopted in America. During the Great Depression, mass mortgage defaults and bank failures caused the home loan market to collapse. In 1934, the U.S. government created the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), the world’s largest public mortgage insurer, to insure private banks’ higher risk, nonprime home loans. In 1938, the Federal National Mortgage Association (FNMA or Fannie Mae) was created to allow low and middle-income buyers to purchase home with subsidized mortgages. In 1968, the Johnson administration privatized Fannie Mae to finance growing budget deficits, also creating the Government National Mortgage Association (GNMA or Ginnie Mae) to provide U.S. government guarantees for MBSs backed by federally insured or guaranteed loans. Two years later, the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation (FHLMC or Freddie Mac) was created, primarily to provide competition for Fannie Mae. Freddie was privatized in 1989.

These government-sponsored entities (GSEs) dominated the U.S. mortgage market. The implicit government guarantee lowered the GSEs’ borrowing costs, reducing the cost of mortgages for borrowers. The GSEs enjoyed tax exemptions and lower capital requirements, allowing them to leverage more than banks. Unable to compete directly with the GSEs, banks developed riskier mortgage lending to borrowers who did not qualify for agency financing.

In the 1980s, the shift to self-funded retirement savings meant houses became a store of wealth. As homeowners paid off their mortgages, the home equity—the value of the houses less the outstanding debt—became a substantial asset, financing consumption and eventually retirement. As maintenance costs, utility bills, and property taxes mean that houses require rather than provide cash, homeowners borrowed against their home equity. Homeowners treated their properties as an automatic teller machine from which they extracted cash. Between 2000 and 2008 Americans drew more than $4 trillion of equity from their homes using home equity loans.

Investors also bought houses and apartments with borrowed money—renting them out, constantly trading up, and increasing the number of properties they owned. During the Internet gold rush, ordinary people abandoned jobs to become day traders. Now, housing day traders emerged, frequently buying off the plan and hoping to sell even before the building was completed.

Books, seminars, and TV series on property ownership outlined the infallibility of housing as an investment, assuming irreversible and continuous increases in home prices. Everyone got on the property or housing ladder. Adam Smith would have recognized the folly: “The chance of gain is by every man more or less overvalued, and the chance of loss is by most men undervalued.”10

Rising wealth from home ownership masked declines in income levels and uncertain employment for the population. Less affected by globalization, housing sustained employment, income, and economic activity. Alan Greenspan approvingly noted one assessment of his early 2000s policy: “The housing boom saved the economy.... Americans went on a real estate orgy. [Americans] traded up, tore down, and added on.”11

In the film It’s a Wonderful Life, George Bailey (Jimmy Stewart) recognizes the fundamental desire of a man for his own roof, walls, and fireplace. The kind banker offers a couple entering their home (financed by a mortgage from his bank) food and wine to celebrate the happy occasion. But houses became an obsession, symbolic of over consumption and excess. In Monty Python’s film The Meaning of Life, the obese Mr. Creosote (Terry Jones) eats an enormous amount, vomits repeatedly, and explodes after eating one last tiny mint. In the housing market, subprime mortgages were the final mint.

Cheaper Cuts of Mortgage

Prime mortgages in the United States, eligible for purchase and securitization by GSEs, conform to fixed guidelines covering the maximum loan amount (until 2008, around $417,000 for a single family home), maximum loan-to-value (LVR) ratios, debt-to-income limits, and documentation requirements. Subprime loans are given to less creditworthy borrowers, unable to qualify for conforming mortgages because of their lower income or uncertain employment histories. Most have damaged credit histories due to late payment of debts or financial problems arising from business failures, illness, or divorce. Some borrowers are subprime because of a lack of credit history—they have never borrowed.

In assessing risk, lenders rely on automated credit scores, a numerical measure of the creditworthiness of a person based on personal data, financial information, and credit history. The most common measure is the FICO score, named after the Fair Isaacs Corporation, which ranges between 300 and 850. In the United States, the median score is 720, with most borrowers scoring between 650 and 800. Borrowers with scores above 620 conform to GSE guidelines. Subprime borrowers typically scored between 500 and 620.

Starting in the early 1990s, governments actively promoted lending to the poor and minority groups. President George Bush sought to increase home ownership and housing affordability: “We can put light where there’s darkness, and hope where there’s despondency in this country...part of it is working together...to encourage folks to own their own home.”12 Construction firms, banks, lenders, and government created the National Homeownership Strategy to enhance availability of affordable housing through creative financing techniques.

The U.S. Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) encouraged financial institutions to meet credit needs of local communities, including low and moderate-income neighborhoods. Tax incentives and mandated targets encouraged GSEs to purchase mortgages and MBSs, including loans to low-income borrowers, expanding the market in securitized subprime mortgages. Legislative changes removed restrictions, allowing higher interest rates and fees for subprime loans.

As casual or part-time employment, self-employment or independent contracting increased; proof-of-income requirements were relaxed. Mortgages against second and third homes, vacation homes and nonowner-occupied investment homes to be rented out (buy-to-let) or sold later (condo flippers) were allowed. HE (home equity) and HELOC (home equity line of credit), borrowing against the equity in existing homes, became prevalent.

Empowered by high-tech models, lenders loaned to less creditworthy borrowers, believing they could price any risk. Ben Bernanke shared his predecessor Alan Greenspan’s faith: “banks have become increasingly adept at predicting default risk by applying statistical models to data, such as credit scores.” Bernanke concluded that banks “have made substantial strides...in their ability to measure and manage risks.”13

Innovative affordability products included jumbo and super jumbo loans that did not conform to guidelines because of their size. More risky than prime but less risky than subprime, Alt A (Alternative A) mortgages were for borrowers who did not meet normal criteria. As lenders decreased standards, there were increases in SIVA (stated income verified assets) loans, where borrowers stated their income without proof, such as income or tax receipts, and NIVA (no income verified assets), loans where no proof of employment was required.

Traditional mortgages provide 70–80 percent of appraised value. More aggressive LVRs, including negative equity loans, where the lender lent more than the value of the house, became available. In the UK one lender offered loans for 125 percent of the value of the property. In the United States undisclosed piggyback loans and silent second mortgages meant that by 2005 the median down payment for first-time home buyers was only 2 percent, with more than 40 percent of buyers not making any down payment at all. The FHA website stated: “FHA-insured loans require very little cash investment to close a loan. There is more flexibility in calculating household income and payment ratios.”

Balloon payment mortgages left a large balance (the balloon) due at maturity. In IO (interest only) loans, borrowers only paid the interest with repayment of principal being deferred. There were ARMs (adjustable rate mortgages) where the interest rate was reset periodically in line with changes in market interest rates. In an option ARM also known as pick’n pay, pick a payment, and pay option, the borrower initially paid a “teaser” rate, below the prevailing market rate. In a 2/28 ARM, the borrower paid the low rate (as low as 1 percent per annum) for 2 years, after which all the payments were adjusted based on market rates at the time for the remaining 28 years of the loan.

Under an option ARM mortgage with a 1 percent teaser rate, a borrower with a $520,000 mortgage would be paying $1,673 per month in the first year versus $3,134 monthly under a 30-year, 6.05 percent fixed rate mortgage. The lower repayments allowed borrowers to take out larger loans. As the initial repayments did not cover the interest, the loan principal increased by the unpaid interest amount (negative amortization). If the price of the home fell, borrowers owed more than the value of the property. After the initial “honeymoon” period, the monthly payments also increased sharply. If the loan balance increases to a set level, generally 110–125 percent of the original amount borrowed, borrowers face sharply higher payments even before the initial period expires.

Alan Greenspan championed ARMs: “many homeowners might have saved tens of thousands of dollars had they held adjustable-rate mortgages rather than fixed rate mortgages during the past decade.”14 In September 2006, Angelo Mozilo, the permanently sun-tanned CEO of Countrywide, a leading American mortgage provider, claimed shock upon discovering that 80 percent of borrowers with option ARMs were making only the very low initial payments.

Never having experienced falling house prices, borrowers bet that home values would go up very fast during the period of the teaser rate, that interest rates would stay low, and that their future income would increase to meet higher repayment. If this proved wrong, then the borrower faced payment shock—a large jump in repayments when the rate was reset. Insiders referred to these mortgages as exploding ARMs.

ARMs Race

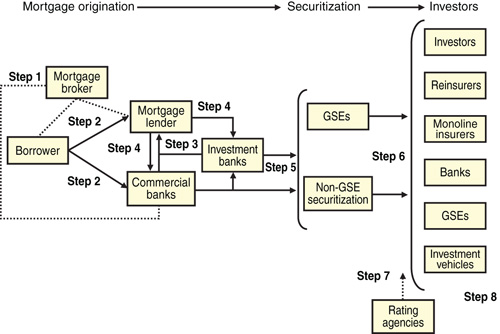

Between 2004 and 2006, subprime mortgages in the United States increased to around 20–30 percent of all new mortgages. By 2007, subprime mortgage outstandings were around 10–15 percent of the total mortgage market of $10 trillion. Securitization evolved into a complex mortgage food chain (Figure 11.5).

Figure 11.5. Mortgage chain

1. Borrowers seek mortgages from banks or specialist mortgage lenders, directly or through a mortgage broker.

2. Mortgage lenders and commercial banks make the loan to the borrower.

3. Mortgage lenders use lines of credit from commercial banks or investment banks (a warehouse line) to finance the mortgages, pending sale.

4. Mortgage lenders sell the loans to larger commercial banks or investment banks.

5. Commercial banks and investment banks securitize mortgages.

6. Conforming mortgages are sold to GSEs (Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac) to be sold as agency MBSs. Nonconforming mortgages (prime jumbo, Alt-A, subprime) are securitized privately without GSE support.

7. Rating agencies provide credit ratings for the MBSs.

8. MBSs are purchased by investors, which include pension funds, insurance companies, mutual funds, individual investors, specialist reinsurers, and monoline bond investors. Other MBS purchasers include banks, GSEs, SIVs and hedge funds.

Fraud by mortgage brokers, lenders, and borrowers reached epidemic proportions, ending in liar loans. In 2005, Mike Molden, a mortgage broker, stated: “I can get a ham sandwich a home loan if the sandwich has a job.”15 To obtain a mortgage, you only needed a pulse or to be able “to fog a mirror”—though even this was not essential, as 23 dead people were approved for new loans in Ohio.

Incentives, designed to maintain and increase volumes, encouraged declines in credit quality. Brokers received an up-front fee based on the size of mortgage—typically 1–2 percent on a conforming mortgage. Brokers received a YSP (yield spread premium) for higher interest rates. Where the market rate was 9 percent, the broker received a YSP of an additional commission of 1 percent for making a loan with a rate of 9.5 percent, or an additional 2 percent if the rate was 10.25 percent. This increased the proportion of subprime loans even where the borrower qualified for conventional mortgages with better terms. Valuations of properties were regularly inflated to allow larger loans.

For lenders like Countrywide, a leading nonbank mortgage lender, the only focus was growth, making more loans. One employee drove a car with the license plate FUNDEM. When a new colleague asked what it meant, he was informed that it was Countrywide’s 2006 growth strategy—to fund all loans. Even if the loan applicant had no job or assets, the answer was always: “Fund ‘em.”16

No one, other than the investor who ended up with the mortgage, had any incentive to make sure that the borrower would pay back the loan. Even these investors chased higher returns, encouraging lower-quality loans to be made and repackaged.

Investors relied on the rating agencies, who relied on banks, brokers, and various third parties to ensure the quality of the loans. Banks and lenders relied on the rating agencies. The brokers relied on the banks that were buying their loans and the investors buying the securities. Everyone relied on someone else to do their job.

The automated models for approving mortgages and rating models for evaluating the quality of ABSs relied on historical data that ignored changes in the mortgage market, especially the deteriorating quality of the loans. They failed to grasp L.P. Hartley’s observation in his novel The Go-Between: “The past is another country; they do things differently there.” In a failure of common sense, smart people spent a lot of time using models and historical data to convince themselves and each other that the risks were low.

Heroes for One Day

In 2008, Adam Davidson and Alex Blumberg of America’s National Public Radio (NPR) produced an award-wining episode of This American Life titled “The giant pool of money.” In the broadcast, Mike Francis, a Morgan Stanley executive director, explained:

We almost couldn’t produce enough to keep the appetite of the investors happy. More people wanted bonds than we could actually produce...it’s like, there’s a guy out there with a lot of money. We gotta find a way to be his sole provider of bonds to fill his appetite. And his appetite’s massive.17

Angelo Mozilo told his troops: “Let’s look for every reason to approve applicants, not reject them.”18

Qualifications required to be a mortgage broker were modest. A sign outside a broker’s office read: “Hair Nails Mortgages.”19 The giant pool of money’ profiled Mike Garner, an employee of Silver State Mortgage, the largest private mortgage bank in Nevada, who entered the mortgage business straight from his previous job as a bartender. Evangelical Christian pastors preached Earthly reward, moonlighting as mortgage brokers selling loans. Church-sponsored wealth seminars promoted home ownership, promising donations to the church in return for loans.

In the film Boiler Room, stockbrokers make cold calls to lists of potential monied clients using high-pressure tactics to sell them shares. In his play Glengarry Glen Ross, David Mamet wrote about the lives of four Chicago real estate agents prepared to lie, flatter, bribe, and threaten to sell real estate to unwilling prospective buyers. Mortgage brokers resembled the characters in Boiler Room and Mamet’s play. They were making money by making loans to poor people with bad credit, selling high-cost mortgages to people who could not afford them. Predatory lending and fraud to close deals were de rigueur.

Some mortgage brokers were making $75,000 and $100,000 a month. In “The giant pool of money,” one mortgage broker described his life style:

We rolled up to Marquee at midnight with a line, 500-people deep out front. Walk right up to the door: Give me my table. Sitting next to Tara Reid and a couple of her friends. Christina Aguilera was doing some.... We ordered three, four bottles of Cristal at $1,000 per bottle...Whoa, who’s the cool guys? We were the cool guys. They gave me the black card with my name on it. There’s probably ten in existence. You know?20

The broker had five cars, a $1.5-million-dollar vacation house in Connecticut, and a rented penthouse in Manhattan.

Daniel Sadek of Quick Loan Funding based in California collected a fleet of cars, including a Lamborghini, a McLaren, a Ferrari Enzo, and a Porsche. Sadek also co-wrote and spent $35 million funding a feature film Redline, starring his girlfriend Nadia Bjorlin. The unlikely plot follows the story of a young automobile fanatic and star of a hot band, who becomes caught up in illegal drag-racing competitions. The film’s message was—risk everything, fear nothing.21

Andy Warhol had forecast a future in which everyone would be famous for 15 minutes. Years later, during his Berlin period, David Bowie penned a song promising everyone that they could be heroes but only for one day. Mortgage brokers were both famous and heroes for a brief time, helping fulfill dreams of American home ownership.

In Bright-Sided: How the Relentless Promotion of Positive Thinking Has Undermined America, Barbara Ehrenreich argues that positive thinking is an ideological force that denies reality. She recounts an encounter with a popular preacher in Houston who preached that God would provide big houses and nice tables in restaurants to those who sincerely wish for them—this was “the Law of Attraction.” Underlying the housing and mortgage boom was manic optimism about house prices.

Subprime lending contributed to increases in American home ownership rates to a high of 69.2 percent in 2004, up from 64 percent in 1994. Between 1997 and 2006 the higher overall demand caused average house prices to double. By late 2006, the average U.S. home cost four times the average family income, an increase from the historical two or three times. As house prices rose, Americans saved less and borrowed more. American home mortgage debt increased to 73 percent of American GDP in 2008, up from below 50 percent in the 1990s.

High house prices put home ownership beyond the means of the people that the policy was meant to assist. Borrowers were forced to enter into expensive creative mortgages to purchase houses. Eventually a surplus of unsold homes and unsustainable levels of borrowings caused housing prices to decline from mid-2006, leaving homeowners with unsustainable levels of debt. Levels of home ownership began to decline.

In 2006, Casey Serin, a 24-year old web designer from Sacramento, bought seven houses in 5 months with $2.2 million in debt. He lied about his income on no document loans. He had no deposit. In 2007, three of Serin’s houses were repossessed. The others faced foreclosure. Serin’s website—www.Iamfacingforeclosure.com—was a symbol of the excesses of the subprime mortgage market.

It was not lending money to poor people that was the problem. The problem was lending money poorly.