12. The Doomsday Debt Machine

Rebranded as structured finance or structured credit, securitization increasingly involved layers of complex leverage repeatedly using the same debt as collateral. The new alphabet of debt that the process created was self-dealing raised to an art form. Debt now bought more debt, as the same underlying loan was leveraged and re-leveraged in a seemingly endless spiral of borrowing. At each stage, the banks charged fees and earned margins from the money they lent.

Alpha-Debt Soup

Investor demand for securitized debt decreased the cost of loans to the borrower, in turn bringing down investor returns. Bankers were forced constantly to create highly rated bonds with attractive returns, repackaging unsellable, rancid junk in complex chains of debt (see Figure 12.1).

Figure 12.1. Securitization market

1. Banks make loans to companies and individuals, including mortgage loans.

2. Banks sell these loans to securitization vehicles that issue ABS, MBS, and CDO securities.

3. Re-securitization vehicles (structured finance CDOs, ABS CDOs, or CDO2) purchase securitized bonds and then repackage them to sell to investors.

4. Re-securitization vehicles buy re-securitized paper issued by each other. CDO3 vehicles buy securities issued by re-securitization vehicles to be further repackaged.

5. Structured investment vehicles purchase loans, primary securitizations (ABSs, MBSs, CDOs) and re- and re-re-securitizations.

6. Investors lend to each other or are otherwise interrelated. Banks provide lines of credit to conduits or lend to SIVs and hedge funds, secured against the securitized bonds purchased. Investment vehicles buy securities issued by each other. Reinsurers and monoline insurers guarantee the banks against losses on securities as well as investing in loans, primary securitizations, re- and re-re-securitizations and the investment vehicles.

7. Investors purchase loans, primary securitizations, re- and re-re-securitizations and invest in the structured investment vehicles and hedge funds. Some investors then borrow from banks to finance these purchases.

ABS CP (asset-backed securities commercial paper), conduits (“arbitrage” off-balance sheet issuers of ABS CP), SIVs (structured investment vehicles) and hedge funds purchased ABSs. SPVs issued short-dated IOUs to money market investors, indirectly taking the risk of ABSs and MBSs that they were not allowed to buy.

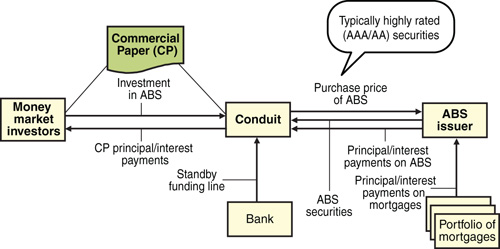

Figure 12.2 sets out a typical ABS CP issuing conduit structure. By early 2007, $1.2 trillion or 53 percent of the $2.2 trillion commercial paper in the U.S. market was asset-backed, around 50 percent by mortgages. There was a mismatch between the 5–30-year securitized debt and the life of the ABS CP (typically less than 6 months). If commerical paper could not be issued (considered highly unlikely), then the sponsor bank would finance the assets under a standby credit facility. SIVs bought high-quality ABS, funding it by issuing their own AAA-rated debt. One SIV even purchased highly rated debt from another SIV in an astonishing chain of risk.

Figure 12.2. ABS CP structure

1. The conduit purchases AAA or AA securities, either ABSs, MBSs, or CDOs, with maturities of between 5 and 30 years.

2. The conduit issues commercial paper with maturities of up to 9 months (mainly 1 to 3 months) to finance the purchase of the AAA or AA-rated securities.

3. As the commercial paper has shorter maturities than the securities the conduit owns, there is a liquidity risk—commercial paper investors may not agree to keep rolling over paper when it matures. To cover this risk, the conduit takes out a standby funding line from a bank (usually the one setting up the structure). If commercial paper cannot be reissued then the conduit can draw down on this standby line to finance the securities it holds.

Hedge funds bought ABSs, funded by borrowing (up to) 98 percent of the value of AAA-rated assets. At Bear Stearns, Ralph Cioffi, a bond salesman, set up the High Grade Structured Credit Strategies Fund and High Grade Structured Credit Strategies Enhanced Leverage Fund. Promising clients steady returns with limited risk, the funds bought high-grade ABSs and MBSs, borrowing heavily against them to increase returns.

Ralphie’s Funds controlled more than $15 billion of assets, funded by $14 billion of borrowings from Merrill Lynch, Goldman Sachs, Bank of America, and JP Morgan. The fees (2 percent of assets under management and 20 percent of profits) accounted for three-quarters of Bear Stearns Asset Management revenues in 2004 and 2005.

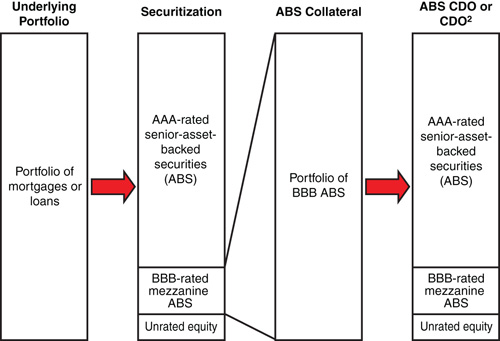

Existing securitized debt was purchased by another SPV and then repackaged into new securitized debt.

These were re-securitizations—structured finance CDOs, ABS CDOs, or CDO2. There were also re-re-securitizations—CDO3. Figure 12.3 sets out a typical ABS CDO or CDO2.

Figure 12.3. ABS CDO or CDO2 structure

1. An underlying portfolio of mortgages and loans is assembled. This portfolio is then repackaged and securitized, being tranched into AAA-rated senior ABS, BBB-rated mezzanine, and equity.

2. The BBB-rated mezzanine from the first securitization is combined with similar securities from other deals to create a new portfolio. This portfolio is then repackaged again and resecuritized into new AAA-rated senior ABS, BBB-rated mezzanine, and equity.

The complex chains of debt and leverage meant that the same loans were being churned in a merry-go-round of investors and banks chasing returns by constantly repackaging and leveraging the same debt over and over.

In the Shadow of Debt

This was the shadow banking system.1 Similar to banks, the unregulated vehicles lent money raised from short-term borrowing and securitization. As the shadow banking system increased in size, risk moved from regulated banks to unregulated vehicles, where it was more difficult to identify.

Like banks, the vehicles assumed the risk that the borrower may not pay back the loan, or that the depositor financing the loan may want their money back. The vehicles held minimal capital or reserves against these risks. The vehicles depended upon the value of their assets remaining stable and also a functioning market where assets could be sold if needed.

Demand for investments from the shadow banking system, the structured bid, drove down borrowing costs. The vehicles constantly increased leverage and risk to maintain returns. Techniques of staggering complexity, incomprehensible to outsiders, created more debt and ever-greater levels of leverage, frequently disguised.

For example, assume a $1,000 million CDO based on a portfolio of 100 separate loans, each $10 million. If any of the loans default, then you lose $6 million (60 percent of $10 million), recovering a part of your loan (40 percent or $4 million). An investor takes the risk of the first 2 percent ($20 million, being 2 percent of $1,000 million) of losses on the entire portfolio (the equity tranche).

Investors in the CDO equity tranche take the risk of bankruptcy of the first three firms out of the 100 firms in the portfolio ($20 million of losses divided by $6 million). As they are first in line to the risk of loss of the first three firms to default, the investors are not diversified. This is because once there are three defaults causing them to lose their entire investment, they have no further interest in the performance of the remaining 97 firms in the portfolio.

Instead of purchasing the equity, the investor could invest $20 million in a diversified fashion, spreading the money equally between each of the 100 loans (that is, $200,000 in each loan—$20 million divided by the 100 loans). If three loans defaulted in the portfolio, then the investor would lose only $0.36 million (loss of $120,000 per company (60 percent of $200,000) times 3). In contrast, where they invested in the CDO equity, for the same three losses the investor loses $20 million. For the same event (three defaults), the investor’s loss is 56 times greater where they purchase the equity rather than investing in a diversified portfolio ($20 million versus $0.36 million). This is known as embedded loss leverage.

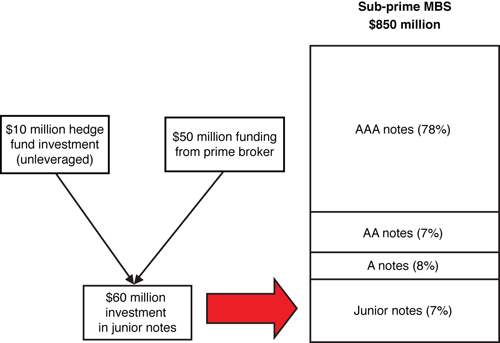

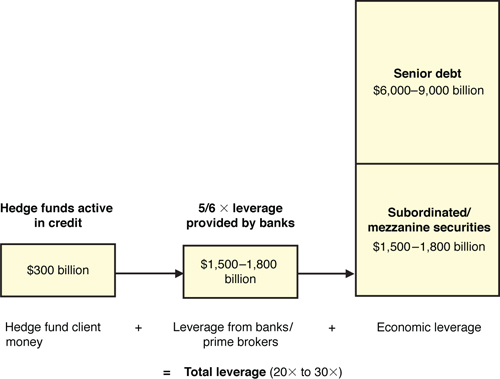

Linked in a dizzy spiral of debt as their modus operandi merged, banks and the inhabitants of the shadow banking sector (ABS issuers, CDO issuers, conduits, SIVs, hedge funds, reinsurers and monoline insurers) increasingly resembled each other. In a case of rinse and repeat and then repeat again, at each stage the risk was redistilled and concentrated. Figure 12.4 shows how a hedge fund uses $10 million to take the risk of the first $60 million of losses on a $850 million portfolio of mortgages.2 Figure 12.5 shows how $1 of real capital now supports between $20 and $30 of loans.

Figure 12.4. Leveraged investment in MBS

1. A hedge fund invests in $60 of the junior notes (effectively the equity tranche) of a securitization of $850 million portfolio of mortgages to create a series of different securities.

2. The hedge fund finances its $60 million with $10 million of its own money, borrowing $50 million from a bank (known as a prime broker) who will lend to it against the security of the notes.

Figure 12.5. Systemic leverage

1. In 2007 there was around $300 billion of funds available from hedge funds active in credit markets that purchased debt securities and loans.

2. The available $300 million could be leveraged five or six times by borrowing $1,200–1,500 billion from banks and prime brokers, against the collateral of securities purchased by the fund. This means that the hedge funds have total buying power of $1,500–1,800 billion.

3. The hedge funds use this $1,500–1,800 billion to purchase riskier subordinated or mezzanine securities in securitizations.

4. The $1,500–1,800 billion supports additional senior debt of four to six times. This is because the subordinated and mezzanine securities absorb losses before the more highly rated senior securities. This provides investors in the senior securities comfort that they are unlikely to lose money, encouraging them to purchase the debt.

5. In total, the original $300 billion of funds now supports $6,000–$9,000 billion in assets, most of which is financed by debt.

Source: Adapted from Roger Merritt and Eileen Fahey ‘Hedge funds: the new credit paradigm’ (5 June 2007), Fitch Ratings, New York. Copyright © Fitch Ratings Ltd.

If the pricing models for ABSs, MBSs, and CDOs were approximate, then for more complex structures they were inadequate. If correlation between two loans in a normal portfolio was an educated guess, then the correlation input into a structured finance CDO, CDO2, or CDO3 was fantasy.

In the 2006 financial statements for the Bear Stearns hedge funds, auditors Deloitte & Touche noted that between 60 and 70 percent of assets were valued using estimates provided by the fund’s managers, cautioning that differences in value could be significant. As Mervyn King, governor of the Bank of England, later observed: “‘My word is my bond’ are old words. ‘My word is my CDO-squared’ will never catch on.”3 King was correct.

Virtual Loans

Finally, loans became completely virtual—they simply did not exist. Loans were even made specifically to fail. Traditionally, lenders owned the loans that they were selling off through securitization. In a synthetic securitization, the lender purchased insurance on loans through a CDS. Increasingly, banks bought insurance on loans they did not own.

Around 2004, looking to make money from the anticipated bust of the housing bubble, a few traders short sold the shares of mortgage lenders like Countrywide, New Century, and Ameriquest, home builders and banks. But the main game was shorting the MBS referenced to the loans.

Investment banks, such as Goldman Sachs and Deutsche Bank, and hedge funds structured CDOs to benefit from the expected decline in house prices. They bought insurance against losses on loans that they simply did not own to benefit from potential defaults on mortgages. The banks and hedge funds paid modest fees (1 to 1.5 percent per annum) to bet against the U.S. housing market. Deutsche Bank’s Greg Lippmann distributed T-shirts emblazoned with the words “I’m Short Your House!!!”4

Magnetar, a hedge fund, had a program totaling $30 billion. The name refers to a neutron star with an extremely powerful magnetic field, which as it decays emits high X-rays and gamma rays. The hedge fund bought mainly BBB-rated mezzanine ABSs that were re-securitized. As the mezzanine part of the capital structure was small (say between 3 and 7 percent), the total size of the deals had to be large. Assuming demand for $30 billion of mezzanine debt, this translated into up to $128 billion of underlying mortgages, compared to total subprime loans of around $450 billion in 2006, 28 percent of the total market.5 As other hedge funds and banks started doing the same thing, volumes exceeded the underlying stock of mortgage loans.

The normal CDS was designed for companies where payment was triggered by bankruptcy or failure to make interest and principal repayments on loans. In June 2005, ABS PAYG CDS (asset-backed securities pay-as-you-go credit default swaps) were introduced. Under this form of credit insurance, buyers of insurance received payments where there was simply a permanent write down in the underlying loans, a downgrade to CCC credit rating or extension of maturity. Traders benefited from any deterioration in the quality of the underlying loans, making it easier to short the housing market.

In 2006, the ABX.HE (asset-backed securities home equity), an index of MBSs similar to a stock index, was created. The ABX allowed trading in portfolios of virtual mortgages—bets on the price of mortgages going up (less defaults and lower loss) or down (more defaults and more losses). Like the CDS on mortgages, the ABX was virtual, unconstrained by the size of the underlying pool of mortgages. All this had nothing to do with providing loans for homes.

In 2006/7, the shorts made a killing as the values of mortgages collapsed when house prices fell and buyers could not make repayments. Many of the securitizations structured by banks performed poorly, resulting in substantial losses for investors. Critics complained that the securitizations were structured specifically with high-risk mortgages to increase the likelihood of loss to the investors and gain to the bank. The banks argued that they had merely structured deals to meet demand from sophisticated investors.

The investors were rarely equal parties in negotiating the deals. The term “sophisticated investor” was an oxymoron, as most barely understood the structures. There was a potential conflict of interest between the banks (shorting the market) and the investors (buying the market). Sylvain R. Raynes, a structured finance specialist, told The New York Times: “When you buy protection against an event that you have a hand in causing, you are buying fire insurance on someone else’s house and then committing arson.”6

Amherst, a small investor, made a killing, by avoiding defaults and preventing foreclosures. Amherst insured $130 million of a pool of $29 million of highly toxic mortgages, more than 4.4 times the actual mortgages in existence. The investment banks that bought protection paid around $100 million to Amherst for the insurance. Amherst then paid off the $29 million of mortgages that it insured, avoiding having to pay out up to $130 million under the insurance policies they sold. The transaction netted Amherst around $71 million (the premium received of $100 million less the amount spent paying off the mortgages—$29 million).

Counting on the Abacus

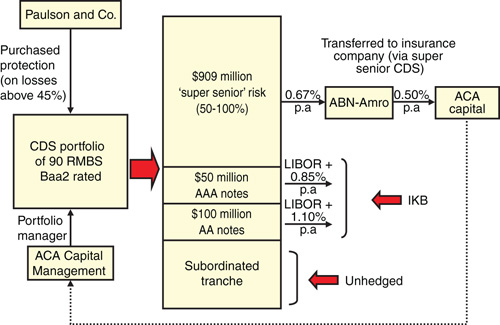

In April 2010, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) filed a lawsuit against Goldman Sachs, dismissed by Kenneth Griffin, the founder of hedge fund Citadel, as “childish.”7 The lawsuit concerned an April 2007 CDO—Abacus 2007 AC1 (see Figure 12.6). Widely used by Asian merchants, an abacus is a calculating tool consisting of a bamboo frame with beads sliding on wires.

Figure 12.6. Abacus transaction

Arranged by Goldman, Abacus was a synthetic securitization, referencing a portfolio of 90 residential MBSs rated Baa2 by Moody’s. The portfolio contained a high percentage of adjustable rate mortgages, relatively low borrower FICO scores, and was concentrated in U.S. states where there had been very high house price rises, like Arizona, California, Florida, and Nevada. ACA Capital Management was the portfolio selection agent. Paulson & Co. purchased protection on losses above 45 percent of the principal on the mortgages. Paulson did not own the mortgages or MBSs, betting that the securities would suffer large losses from the housing collapse.

Goldman placed $50 million AAA notes, paying LIBOR plus 0.85 percent per annum, and $100 million of AA notes, paying LIBOR plus 1.10 percent per annum, with IKB, a German bank. Goldman paid 0.67 percent per annum to hedge its super senior risk with ACA Capital, a reinsurance company (parent of the portfolio selection agent). Dutch bank ABN-Amro was interposed between Goldman and ACA Capital to guarantee ACA’s performance, for a fee of 0.17 percent per annum.

In October 2007, 6 months after completion, 83 percent of underlying Baa2 RMBSs was downgraded. By January 2007, 8 months after completion, 99 percent of underlying securities had been downgraded. Paulson made $1 billion on its CDS position as the mortgages lost all value. IKB lost its entire $150 million investment. With ACA in financial difficulties, RBS, who purchased ABN-Amro, lost $841 million on the super senior CDS.

There were parallels to 1929 and the Goldman Sachs Trading Corporation, a listed investment trust. After the crash, at a 1932 U.S. Senate hearing, there were questions about the transaction:8

In 2010, the SEC alleged that Goldman misled investors by not disclosing material information on Paulson’s intention to short MBSs. They alleged that Paulson, not ACA, selected the portfolio, which was designed to maximize losses from a housing collapse.

Goldman argued that full details of the RMBSs were disclosed and ACA was a reputable manager and had selected the portfolio as stated. There had been no representation that Paulson owned the underlying RMBSs. Any short position taken by Goldman was hedging its own RMBS positions. Goldman, who made $15 million for arranging the transaction, claimed to have actually lost $90 million. Goldman’s claim, that IKB was a sophisticated investor, elicited humorous comments. In Michael Lewis’ The Big Short, a trader shorting the mortgage market asks: “Who’s on the other side, who’s the idiot?” The answer is: “Düsseldorf. Stupid Germans. They take rating agencies seriously. They play by the rules.”9

Intellectual Masturbation

Examination of several terabytes (billions of pages) of emails revealed Tom Montag, a senior Goldman executive, describing one CDO, Timberwolf, as: “one shi**y deal.” Matthew Bieber, the trader responsible, considered the day that Timberwolf was issued as “a day that will live in infamy.” Like Abacus, within 5 months of issuance, Timberwolf, whose investors included Bear Stearns’ hedge funds, lost 80 percent of its value.10

During a Senate hearing, Goldman’s CFO David Viniar was asked: “when you heard that your employees, in these e-mails, when looking at these deals, said God, what a shi**y deal...do you feel anything?” Viniar responded: “I think that’s very unfortunate to have on e-mail.”11 Goldman instituted policies against using swear words in emails, cleaning up language rather than sales practices.

The SEC indictment cited Fabrice Tourre, a French employee of Goldman, who sold the Abacus deals to unwitting “widows and orphans.” Among tender emails to his girlfriend Serres, the “super-smart French girl in London,” the self-styled “Fabulous Fab” observed in January 2007:

More and more leverage in the system. The whole building is about to collapse anytime now?.?.?.? Only potential survivor, the fabulous Fab[rice Tourre] standing in the middle of all these complex, highly leveraged, exotic trades he created without necessarily understanding all of the implications of those monstrosities!!!

Abacus was “pure intellectual masturbation,” “a “thing,” which has no purpose, which is absolutely conceptual and highly theoretical and which nobody knows how to price.”

Tourre had no self-doubt:

Anyway, not feeling too guilty about this, the real purpose of my job is to make capital markets more efficient and ultimately provide the U.S. consumer with more efficient ways to leverage and finance himself, so there is a humble, noble, and ethical reason for my job:) amazing how good I am in convincing myself !!!12

Tourre insisted that he reasonably relied on material prepared by other Goldman staff. His insouciant Gallic defense stated that “he cannot be liable for any omissions that he did not make.”

In July 2010, Goldman settled, paying a $550 million fine, around 4 percent of its annual earnings of $13 billion. Charles Geisst, author of A History of Wall Street, was unimpressed: “a fine is not going to bother these people.... [It] is like passing around the church collection plate and collecting a few extra bucks for sins.”13 Goldman admitted that statements in the Abacus marketing material that the reference portfolio was “selected by” ACA without disclosure of Paulson’s role and economic interests, which were adverse to CDO investors, were incomplete.

The settlement avoided the real issue—the conflicts of interest within investment banks. Goldman Sachs feared that the separation of client business and trading with its own capital limited its ability to compete. Under CEO Lloyd Blankfein, the son of a postal worker born in the Bronx, Goldman embraced the conflict, emphasizing intelligence from trading with clients and other banks to place bets with its own money. As a former counsel to the Federal Reserve Board observed:

It’s all about the score. Just make the score, do the deal. Move on to the next one. That’s the trader culture. Their business model has completely blurred the difference between executing trades on behalf of customers versus executing trades for themselves. It’s a huge problem.14

Used to Be Smart

Smart banks now drank their Kool-Aid, investing their own money aggressively in ABSs. Bankers had not grasped painter Robert Motherwell’s observation that “the deep necessity of art is the examination of self-deception.”

Originally a self-help movement for artisans based in Newcastle, Northern Rock for much of its 150 years in existence took deposits from savers and lent to people to buy homes. Originally owned by its members, in 1997 the company demutualized and offered its shares on the London Stock Exchange. Between 1997 and 2007, under CEO Adam Applegarth, Northern Rock’s loan portfolio increased from £16 billion to £101 billion, a rate of more than 20 percent per annum. Northern Rock’s share of the UK’s residential mortgage market more than tripled from 6 percent to 20 percent in ten years. One mortgage product allowed homebuyers to borrow 125 percent of the value of the home, or up to six times their income.

As growth outstripped the ability to finance loans from deposits from its customers, Northern Rock relied on securitization, arguing that issuing MBSs provided access to large pools of money from investors, cheaper borrowing costs and shifted the risk away from Northern Rock. Northern Rock issued £17 billion of MBSs in 2006 alone. In early 2007, bankers reaping large fees from Northern Rock securitizations voted them the best financial borrower in capital markets. In late 2007, Northern Rock’s dependence on securitization would destroy it when the market failed.

CitiGroup, Merrill Lynch, and UBS committed seppuku, ritualized suicide. New regulations, low interest rates, and stable markets led banks to borrow more to invest in securitized bonds. At Merrill Lynch the strategy was known as a “million for a billion”—a million dollars in bonus money for every billion the bank invested in mortgage securities.

Under changed banking regulations (known as Basel 2), credit ratings and the bank’s own models were used to calculate risk and set the amount of capital required. Under the new system, AAA and AA assets attracted minimal capital: 0.5–0.6 percent of the asset.

Following its merger and struggling to meet market expectations, Citi increased risk taking, armed with analysis from a consulting firm that Citi’s risk taking lagged competitors. Chairman of the executive committee, Robert Rubin, former head of Goldman Sachs and secretary of the Treasury under President Clinton, was at the center of this push, arguing that “the only undervalued asset is risk.”15 Citi’s “riverboat gamblers” created a production line to buy mortgages and repackage them into MBSs.16 The high credit quality securities were sold to ABS CP conduits and SIVs, managed by Citi or increasingly, retained on the bank’s books. Citi’s trading desk’s motto was “Live for today.”17

Having worked his way to CEO of Merrill Lynch, America’s largest brokerage firm, Stanley O’Neal, the grandson of a slave, struggled to change the firm, known to its employees as “Mother Merrill.” Merrill Lynch’s bovine image was related to a 1970 TV commercial featuring a thundering herd of cattle stampeding straight at the camera and the tagline “Merrill Lynch: bullish on America.” Like Citi, “Stan Bin Laden” or “Osama O’Neal” was bullish on risk, especially mortgages.

In 2006, Merrill Lynch purchased mortgage broker First Franklin for $1.3 billion to provide raw material for its securitization machine. Merrill’s portfolio of securitized mortgages peaked at $50 billion. Lacking Citi’s vast balance sheet and capital, Merrill hedged some risk with reinsurers and monoline insurance companies, many of whom would turn out to be under-capitalized.

A large respected Swiss bank, UBS had a logo of three keys, signifying confidence, security, and discretion. Originally focused on private banking, UBS increased exposure to investment banking through its acquisition of S.G. Warburg, Dillion Read, and PaineWebber. UBS also invested heavily in securitization.

An internal report, prepared after UBS suffered large losses, revealed rampant risk taking.18 Every UBS desk (internal hedge fund, bond trading, currency trading, funding) and every trading strategy (ABS relative value strategy, ABS CDO trading, and overall relative value trading) involved purchases of high-quality MBSs or CDOs. If you only had to hold 0.6 percent capital against the security, then a margin on 0.15 percent per annum translated into a return of 25 percent per annum (0.15 percent divided by 0.6 percent), well above the bank’s target. Irrespective of the relationship between loan defaults, the correlation between traders and trading strategies was high.

At UBS, investments were financed with cheap money from the bank’s depositors. Glass-Steagall was originally enacted to prevent depositors money being risked in this way. The banks did not heed the advice of economist Walter Bagehot in his 1873 book Lombard Street: “The only securities which a banker, using money that he may be asked at short notice to repay, ought to touch are those which are easily saleable and easily intelligible.”19

Citi and Merrill would lose more than $50 billion each, whereas UBS would lose more than $30 billion. Chuck Prince, Citi’s CEO, a lawyer appointed to deal with regulatory problems, lacked the requisite risk skills. Robert Rubin abnegated responsibility, citing his lack of operational responsibilities. Prince’s nickname was “One Buck Chuck,” a reference to the fact that Citi’s stock price barely moved $1 under his leadership. Losses on mortgages drove Citi’s stock price perilously close to the one-buck figure as the bank struggled to survive. Merrill was taken over by BA, after a short and troubled period with John Thain at the helm. UBS survived with the assistance of the Swiss government. UBS, observers noted acidly, meant ugly balance sheet, used to be smart, or u be stupid.

Warren Buffet and Charlie Mauger at Berkshire Hathaway believed that investors should eat their own cooking, that is, have their money at stake. In 2010, John Mack, CEO of Morgan Stanley, ruefully observed that the banks “did eat our own cooking and we choked on it.”20

Chain Reaction

In an atomic chain reaction, a sequence creates additional reactions as positive feedback leads to a self-amplifying chain of events. In late 2007, a similar chain reaction started in securitization markets. In 2004, U.S. interest rates rose from their abnormally low levels after 2001. U.S. housing prices stalled, then fell, and mortgage defaults increased, especially on subprime loans. In a 2007 report, the Center for Responsible Lending predicted that 15 percent of loans would end in foreclosure. In the third quarter of 2009 alone, 15 percent of subprime loans were foreclosed, while another 27 percent were delinquent.

Homeowners, who qualified for mortgages based on gambling income and eBay earnings, defaulted within months of drawing down the loan. In securitizations, originators were obligated to repurchase loans if they went delinquent within an agreed time. As mortgages defaulted, the brokers did not have the money to buy them back.

In a February 2007 conference call, New Century Financial, a California-based major subprime mortgage lender, warned that loan volumes would decrease by 20 percent because of early defaults. New Century had $8.2 billion in repurchase obligations and was in default on its lines of credit. New business had ground to a halt, reducing cash flow and earnings.

In 2002 HSBC, the once staid conservative Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank, purchased Household Finance, a subprime pioneer. In February 2007, HSBC wrote off $10.56 billion in loan losses. HSBC management once spoke in glowing terms of Household’s staff—of Ph.D.s skilled at cutting and dicing mortgages. In hindsight, HSBC should have stuck to old-fashioned bankers able to establish the borrower’s ability to repay by means developed during the Spanish inquisition. As bankers say: “The best loans are made during the worst times, the worst loans are made during the best times.”

By September 2009, one in ten U.S. householders were at least one mortgage payment behind. If foreclosures were included, then one in seven American homeowners were in housing distress. In subprime, delinquencies in some kinds of loans were 40–50 percent. The dream of home ownership had become a national nightmare.

Speaking before the Joint Economic Committee of the U.S. Congress on March 28, 2007, Ben Bernanke appeared unconcerned: “The impact on the broader economy and financial markets of the problems in the subprime markets seems likely to be contained.” The Fed chairman had probably never heard of James Howard Kunstler or read his prophetic warning of October 17, 2005:

The mortgage industry, a mutant monster organism of lapsed lending standards and arrant grift on the grand scale, is going to implode like a death star under the weight of these nonperforming loans and drag every tradable instrument known to man into the quantum vacuum of finance that it creates.21

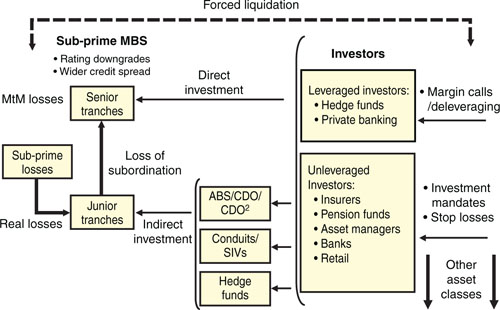

Subprime losses radiated out, infecting the entire global financial system (see Figure 12.7). Loan losses meant that the riskier equity and mezzanine tranches of securitized mortgages were worthless. Paradoxically, the major problem related to high-quality-rated securities unlikely to suffer cash loss. In a typical securitization, losses would need to reach 15–30 percent before the better-rated securities lost money. As losses mounted and the lower layers on which the high rating of senior securities was based disappeared, AAA tranches were downgraded. Simultaneously, credit margins increased. Investors had paper or mark-to-market losses if the securities were sold today. If the investor could ignore the current value, then the investor was unlikely actually to lose money.

Figure 12.7. Transmission of subprime losses

Traditional investors who had not themselves borrowed to buy the securities found themselves having to sell as paper losses reached certain levels, triggering real losses. They were also indirectly caught up in the death throes of leveraged funds. Unable to borrow directly, they had invested in hedge funds, SIVs and CDOs to access the hidden fruit of leverage.

As the value of the securities used as collateral fell, investors who had borrowed found lenders asking for more collateral. Hedge funds, conduits, and SIVs did not have the money to meet the margin calls. Forced selling set off of a new round of price falls, restarting the entire cycle.

At Bear Stearns, Ralphie’s Funds owned AAA and AA-rated MBSs funded by $600 million in equity and $10 billion in short-term borrowings. In good times, the leverage ensured good returns but now it worked in reverse. A 1 percent fall in the value of the fund assets was roughly equivalent to a loss of $100 million (about 16 percent of the equity). A 6 percent move wiped out all equity investors. A 24 percent fall in the value of the underlying bonds translated into a $1.8 billion loss for the lending banks.

Bear Stearns agreed, under pressure, to provide a $1.6 billion loan (over 10 percent of the firm’s equity) to the less leveraged High Grade Structured Credit Fund, letting its more leveraged sibling fail. Jimmy Cayne, cigar-smoking, bridge-playing, and (allegedly) pot-smoking Bear Stearns’ CEO, sought a one-year moratorium on margin calls. In 1998, when Wall Street bailed out Long Term Capital Management (LTCM), Bear famously rejected a similar proposal. Merrill, a big lender, now seized and tried to auction off $800 million of collateral. There were few buyers in sight and the prices were in free fall.

Shortly after the Bear funds collapsed, the UK hedge fund Peleton Partners (the name refers to the leading group in a bicycle road race) failed. Following a similar strategy to the Bear Stearns funds, Peleton had recently won an industry award for best new fixed-income hedge fund.

Phase Transition

Banks with mortgage assets suffered large losses because borrowers failed to pay their mortgages. The models used to value securitized bonds, especially the default correlation model, failed, exacerbating the loss. Will Rogers was vindicated: “You can’t say that civilization don’t advance; for in every war they kill you a new way.”

In the Ising model, within a lattice of interacting magnetic moments, heat causes the direction of the magnetic moments to be uncorrelated, behaving randomly. Where the temperature drops below a critical temperature, the magnetic moments become spontaneously correlated. This is a phase transition in thermal mechanics and spontaneous symmetry breaking in statistical quantum field theory. As long as the economy’s temperature was high, loan defaults were uncorrelated and risk was low. When the economy’s temperature dropped, the correlation between defaults as well as the level of defaults increased. As the economy experienced a phase transition, losses and risk increased to catastrophic levels.

Increases in default correlation caused the value of highly rated tranches to fall as the probability of defaults and higher losses increased. Reinsurance companies and monoline insurers that had hedged mortgage exposures now experienced spontaneous symmetry breaking, failing in sympathy with the defaulting mortgages leaving the banks that they had insured exposed. As the markets seized up, banks were left with low-quality loans that they were unable to repackage and sell off, as planned.

Despite minimal exposure to subprime mortgages, Northern Rock was unable to raise money as the securitization market seized up. In mid-September 2007, queues of panicked customers outside Northern Rock branches waited to withdraw deposits. In the Internet banking age, the signs of an old-fashioned bank run sealed Northern Rock’s fate. Adam Applegarth confessed to a UK parliamentary hearing that he understood: “the logic of somebody who has their life savings invested in an institution and who sees pictures of people queuing outside the door and they go join that queue.”22

Unable to issue commercial paper as holdings of toxic assets fell in value, conduits triggered parent bank credit lines, returning the assets to the mother ship. SIVs unable to issue debt faced the choice of trying to sell their assets or file for bankruptcy and liquidate their investments. Although there was no legal obligation to do so, sponsoring banks were forced to support their off balance sheet vehicles to preserve their reputation.

In an interview, Robert Rubin admitted that he had no knowledge of the liquidity put mechanisms under which assets held by Citi’s shadow banks could come back to the firm.23 The risks, including the liquidity put, were disclosed in the financial statements. One trader who briefed Boards observed: “These guys wouldn’t know a CDO from a PowerBar and they didn’t want to learn.”24

Terra incognita

In the years preceding the financial crisis, the United States absorbed around 85 percent of total global capital flows ($500 billion each year). Asia and Europe were the largest suppliers of capital, followed by Russia and the Middle East. This money funded U.S. government debt, the housing market and high levels of home equity lending.25 Global money funded the U.S. debt binge and global investors suffered losses. In 2007 Jochen Sanio, a German regulator, asked: “Does anyone know who holds the risk [in modern financial deals]?...Market participants are operating in terra incognita.”26

In Australia, one of the last terra incognitas, the local arm of Lehman Brothers sold $2 billion of CDOs (grandly named Federation, Tasman, Parkes, Flinders, Kokoda, Kiama, and Torquay) to Tumbarumba Council, Wingecarribee Council, St. Vincent De Paul Society, the Starlight Children’s Cancer Foundation, the Boystown Charity for underprivileged children, and the Anglican, Baptist, Uniting, and Catholic churches. Tax money to fund civic works and charitable donations were invested in these securities.

Like their counterparts elsewhere, Australian investors did not understand the risks and did not receive sufficient return to compensate for the additional risk. Investors relied on credit ratings, assuming that the securities were just like conventional bonds. ABS, MBS, CDO, and others were terra nullius—there was nothing there.

Banks, especially senior managers and directors, did not understand the products that they were creating and selling. Risk was broken up into exotic fragments that were difficult to understand and value. David Skeel and Frank Partnoy in a study of CDOs concluded that the costs were high, the benefits questionable and that the structures were used to transform existing debt instruments that are accurately priced into new ones that are overvalued.27 Warren Buffett told the Financial Times on October 26, 2007:

One of the lessons that investors seem to have to learn over and over again, and will again in the future, is that not only can you not turn a toad into a prince by kissing it, but you cannot turn a toad into a prince by repackaging it. But very imaginative people in the securities market try to do that. If you have bad mortgages they do not become better by repackaging them.

Investors learned the rules of financial gravity.28 If the value of the whole is less than the price of its parts, then some parts are overpriced. Separating out and selling risk through securitization was not necessarily a source of value. If you segment value, then you also segment liquidity. You have many securities with a smaller market for each part. When you want to sell, there are no buyers. Risk transfer encourages people to take more risk and to shift risks to those least able to understand and bear them. There is a strong correlation between the complexity of an instrument, its remoteness from the real economy and its likelihood to spread contagion.

In a Tom Satherwaite short story Masquerade, the American hero eats andouillettes. Finding them initially delicious, he is later horrified to discover that they are pigs entrails stuffed with tripe and chitterlings, offcuts, and rejects of his own culture. Securitized bonds were the andouillettes of high finance.

By 2007 CDOs came to mean Chernobyl death obligations.29 In an atomic explosion, deadly radiation causes a slow, painful death for those not killed by the blast. Half-life measures the rate of radioactive decay, which can range from seconds to 760 million years for Uranium 238. Toxic assets from collapsed securitization markets emitted toxic radiation that lingered, poisoning financial markets.

Securitization was alchemy, creating, multiplying, and refracting borrowing for a debt-addicted world. Designed to allow transfer and reduction of risk, it ended up burning everything and everybody it touched.