13. Risk Supermarkets

On August 4, 1930, Michael Cullen opened King Kullen, the first supermarket in Jamaica Queens in New York City, aiming to sell large volumes at discounted prices. King Kullen’s marketing slogan was: “Pile it high. Sell it low.” Increasingly resembling financial supermarkets, banks packaged risk into discrete, tradable bundles, known as derivatives.

Derivatives have no intrinsic worth, deriving their value from an underlying financial asset—share, bond, commodity, or currency. They allow hedging the risk of changes in the price of assets. Peter Bernstein argued that: “The revolutionary idea that defines the boundary between modern times and the past is the mastery of risk: the notion that the future is more than a whim of the gods and that men and women are not passive before nature.”1 Mastery of derivative instruments, the tool for managing risk, defined the new finance. Derivatives were the ultimate in financial alchemy—the powerful, magic “ring” that allows the holder to rule and control money.

Mind Your Derivatives

Derivatives are a system of price guarantees and price insurance. Forwards (known as futures when traded on an organized exchange) guarantee the price at which you can buy or sell something at a future date. If the copper price goes up, then a copper mining company earns more from its sales. If the price goes down, then it earns less. If the mining company wants to guarantee the future price of copper, then it sells its copper forward to an agreed date at a known price to guarantee revenues.

Options offer price insurance. By selling forward, the mining company gives up potential gains from higher than expected copper prices. Instead, the mining company could purchase a put option that protects against declines in the copper price. If copper prices fall then the put option pays the difference between actual market price at the future date and the agreed price (the strike price), compensating the mining company for losses. If prices are above the agreed strike price then the option lapses, allowing the mining company to benefit from higher copper prices. To purchase the put option, the mining company (the option buyer) pays a fee (the premium) to the provider of the insurance (the option seller). A call option protects a copper purchaser, for a fee, from higher prices by paying out the difference between the actual market price of copper at the future date and the agreed price if prices go up.

Derivatives have a number of special features, which make them attractive. The copper mining company does not actually deliver the copper to the providers of price guarantees or insurance but settles in cash, based on price changes from the time the contract was struck. If copper prices go down, then the mining company receives a payment from the price guarantor to compensate for lost revenue. If copper prices go up, the copper mining company makes a payment to the price guarantor from its higher earnings. If the copper mining company bought price insurance, then it receives only a payment if the copper price falls. Cash settlement allows traders with no position in copper to buy or sell to take advantage of expected price changes.

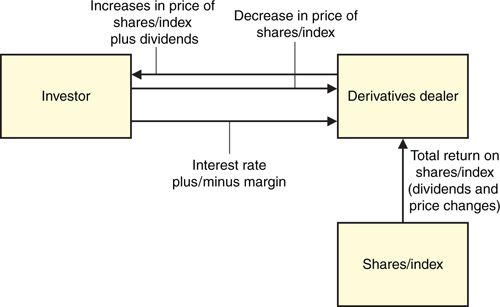

Using derivatives, traders can also bet on future price changes without commitment of money to actually buy the asset. Instead of buying $10 million of shares with cash, the trader can enter a derivative, a total return swap (TRS) over the shares (see Figure 13.1). The trader receives the return on the share (dividends and increases in price) in return for paying the cost of holding the shares (decreases in price and the funding cost of the dealer). The TRS requires no funding other than any collateral required by the dealer, substantially less than the $10 million required to buy the shares. The trader acquires the same exposure as buying the shares but increases the return and risk through leverage.

Figure 13.1. Total return swap over shares

Derivative contracts are also difficult to account for under accounting systems that date back to the Renaissance. They are off-balance sheet because all payments take place in the future. The special characteristics of derivatives allow their use to circumvent accounting regulations, investment rules, securities and tax legislation.

Particle Finance

Derivatives trading in a world where people merely hedge risk requires a party with an equal but opposite exposure to price movements. For example, the copper mining company could trade with an electronics manufacturer exposed to higher copper prices. As someone with an equal but opposite position or view on future price movements is not always available, banks increasingly supplied the derivatives. They managed the risk by trading in the underlying assets, using the Black-Scholes option pricing model. Banks now used the models to create and trade endless varieties of derivative products.

In his story The Lottery of Babylon, the Argentinian author Jorge Luis Borges describes a world of infinite combinations emerging from infinite subdivision where “no decision is final; all branch into others.”2 Derivatives increasingly resembled the Babylonian lottery. Like matter, financial instruments were now fractured into risk particles to be reconstituted at will using derivatives. In physics, electrons, neutrons, and protons gave way to quarks, leptons, and the probabilistic world of quantum theory. Derivative finance also became more complicated as complex derivatives divided and multiplied risk exponentially.

Quants, highly qualified POWS (physicists on Wall Street),3 created derivative products that sometimes defied comprehension. There were swaps (price guarantees) as well as caps, floors, and collars (different types and combinations of options). There were exotic options—knock-in, knock-outs, digitals, one-touch, rainbows, worst-off, quantos. Most derivatives were on interest rates, bonds, currencies, shares or commodities. There were also derivatives on inflation, economic statistics, property prices, freight rates, catastrophe risk (hurricanes and earthquakes) and the weather. Emission derivatives were promoted as a way of combating climate change.

Just as the laws of classical physics alter at the quantum level, the rules of finance operate differently at the derivative level. Particle physics could generate electricity or create weapons of unimaginable power. Like nuclear weapons, derivatives were the culmination of centuries of intellectual endeavor. In 2002 Warren Buffett described derivatives “as time bombs both for the parties that deal in them and the economic system.... In our view...derivatives are financial weapons of mass destruction, carrying dangers that, while now latent, are potentially lethal.”4

Derivatives now allowed trading of risks, increasingly for speculation. Even where used to manage risk or investments, derivatives frequently introduced new risks with unintended consequences.

Hedging Your Bets

In Liar’s Poker (by Michael Lewis), the potent threat to the Salomon Brothers recruits is that if they do poorly in the training program, they might end up in municipal finance, munis. Municipal finance, where local governments raise funds to build schools, roads, and sewers was a backwater, safe, stable, and boring job, at least until they started dabbling in derivatives.

Jefferson County, Alabama, is centered on the iron, coal, and limestone belt in the Appalachian Mountains. The County seat, Birmingham, was the center of the civil rights struggle in the 1950s and 1960s. By 2008, Jefferson County was near bankruptcy, as a result of derivative transactions—supposedly hedges reducing risk.5

In 1993, three taxpayers, later joined by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, filed a lawsuit against the County alleging discharge of untreated sewage into the Cahaba river watershed. As part of a settlement, the County agreed to build a sewer system collecting overflows and cleaning the water. The original $3.2 billion cost ultimately doubled. Between 1997 and 2002, Jefferson County issued $2.9 billion in sewer bonds.

In 2002, bankers advised refinancing the debt using adjustable rate bonds and interest rate swaps, saving millions of dollars in interest cost. In an adjustable rate bond, the interest rate is reset periodically by reference to market rates. Between 2002 and 2004, Jefferson County issued more than $3 billion of adjustable rate bonds, predominantly auction rate securities (ARSs), bonds with a long maturity where the rate is regularly reset through a Dutch auction6 typically held every 7, 28, or 35 days.

ARSs provided borrowers with low cost, adjustable rate debt. Institutional investors and high-net-worth individuals received a higher interest for short-term investments because of the assurance of liquidity through the auction process. The investor’s risk was low, as highly rated bond or monoline insurers guaranteed repayment.

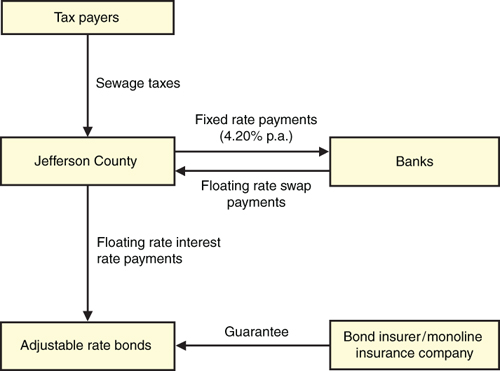

Jefferson County entered into interest rate swaps, with JP Morgan, Bank of America, and Lehman Brothers, to hedge its exposure to fluctuating interest rates. Under the swaps, the County paid a pre-agreed fixed rate in return for receiving floating rate payments. Where the payments received matched the payments under the adjustable rate bonds, the swaps converted the County’s debt into fixed rates, guaranteeing a fixed cost of approximately 4.2 percent for 40 years. Figure 13.2 sets out Jefferson County’s financing transactions. The County saved money, in the process building the largest portfolio of swaps ($5.8 billion) among US counties.

Figure 13.2. Jefferson County swaps

Sewer Bonds

Proud of its success, Jefferson County held seminars, educating other counties in sophisticated financing techniques. Wall Street bankers extolled the advantages of derivatives with sessions like “Derivatives: getting the right deal done right.” Bankers quoted Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan’s enthusiastic advocacy of derivatives: “New financial products have enabled risk to be dispersed more effectively to those willing, and presumably able, to bear it.”7

The transactions assumed that the floating rate received under the swap matched the floating rate paid on the adjustable rate bonds. ARS rates are based on money market rates, like 1-month London Inter-bank Offered Rate (LIBOR) or the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association (Sifma) municipal swap index. Jefferson County paid fixed rate and received a floating rate of, say, 67 percent of one-month LIBOR. Historical studies going back to 1986 showed that the notes typically trade at 67 percent of 1-month LIBOR. If the relationship did not change (known as basis risk), Jefferson County saved between 0.75 and 1.25 percent per annum.

In January 2008, when monoline insurers were downgraded by rating agencies because of exposure to subprime mortgage debt, the ARSs guaranteed by them also got downgraded. Investors exited the ARS market and auctions failed. Where there is an auction failure, the rate increases to a pre-agreed maximum level, as high as 20 percent, to compensate investors unable to sell their investments. In February 2008, Jefferson County’s interest rate rose to 10 percent from 3 percent. The interest costs of Jefferson County’s sewer debt reached more than $250 million, against the $138 million in revenue the system produces.

As the ARS interest rate went up, receipts under the swaps fell as central banks cut interest rates. The receipts supposed to track the County’s adjustable bonds now added to its costs. Long-term interest rates fell sharply, causing losses on the swaps. The downgrade in Jefferson County’s rating required lodgement of cash to cover the loss under the swap. If the County did not meet this margin call, the banks had the right to cancel the swaps, at a cost of $277 million. In March 2008, Jefferson County failed to post collateral and defaulted under the swaps.

As Jefferson County’s sewer bonds were downgraded to junk status, the banks left holding unwanted ARSs became entitled to cancel arrangements to act as buyers of last resort in auctions and force the County to buy back its bonds. Downgrading the sewer bonds, Moody’s noted “the unique, risky structure of Jefferson County’s highly leveraged debt portfolio, which is hedged by swaps and comprised almost entirely of insured variable-rate demand bonds and auction-rate securities, and hedged by interest rate swaps.”8 Earlier, the agency had concluded that the County’s use of derivatives to manage its debt portfolio did not present undue risks for bondholders.

The County increased taxes and cut back services. Residents faced the choice of paying heating bills or paying the water and sewer bill, which had increased fourfold in the past decade. School children were asked to bring toilet paper, soap, and paper towels to school, as the County could no longer afford them. Residents sold replica sewer bonds as toilet paper and distributed bumper stickers saying “Wipe out sewer debt.” Having survived the U.S. Civil War and racial strife, Jefferson County scrambled unsuccessfully to avert the biggest municipal bankruptcy in U.S. history.

Harvard Case Studies

Located in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University is a long way from Alabama. In 2005, Lawrence (Larry) Summers, the 27th president of Harvard, announced a major campus expansion. A Harvard Ph.D. in economics and a tenured professor since 1982, Summers served as chief economist of the World Bank and secretary of the Treasury in the Clinton Administration. He told Faculty of Arts and Sciences professors in May 2004 that: “The only real limitation faced by the Faculty was the limit of its imagination.”9

Harvard’s financial position was strong, with its $22.6 billion endowment fund returning 16 percent per annum during the previous decade. To finance the expansion, Harvard issued bonds, planning to borrow $1.8 billion in 2008 and a further $500 million through to 2020. In December 2004, Harvard entered into $2.3 billion interest rate swaps to lock in financing costs at historically low rates.10 The university gained budgetary certainty—a hedge.

In 2008, as credit markets seized up and central banks slashed rates, the swaps went into loss because Harvard was contracted to pay higher rates than current market rates. As the value of the contracts plunged, Harvard, like Jefferson County, was forced to lodge cash with its bankers, coinciding with a fall in the value of Harvard’s endowment fund of 30 percent (from $36 billion at its peak to $26 billion). Its cash account used to fund ongoing expenditure lost $1.8 billion.

To limit losses, Harvard borrowed money to terminate the swaps, paying $498 million to banks during 2009 to cancel $1.1 billion of interest rate swaps. It agreed to pay $425 million over 30–40 years to offset an additional $764 million in swaps. Harvard implemented austerity measures—freezing salaries, reducing staff, and cutting capital spending, including the planned expansion. Harvard’s swaps had created a liquidity crisis of their own, which no one, least of all Summers, had imagined.

Along with Robert Rubin and Alan Greenspan, Summers was instrumental in defeating the U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission’s attempt in 1998 to regulate over-the-counter derivatives, including interest rate swaps. In 2009 Summers, now director of President Obama’s National Economic Council, sought to regulate the derivatives market “to protect the American people.”

The Italian Job

Europeans once had the art but only Americans had the money to buy it. Now, Americans had the financial engineering and Europeans adopted the ideas. As Summers boasted: “what Harvard does and says has an enormous resonance that goes beyond ZIP code 02138.”11

In 2009, Alfredo Robeldo, an Italian prosecutor, began an investigation of financing arrangements for the City of Milan. In 2005, Milan restructured existing debt and cash into a €1.68 billion bond. Four banks arranged Europe’s biggest-ever municipal bond sale at a fee of just 0.01 percent of the face value of the bonds, well below the normal fees of 0.3–0.45 percent. The City of Milan and the banks simultaneously entered into two derivatives—a complex amortizing swap converting the fixed rate bond into floating rate and a contract that allowed Milan’s interest cost to fluctuate within certain ranges.

Milan used the new borrowing to pay off old loans and cancel related swaps. Milan owed the banks €96 million upon termination of the old swaps. Milan paid the banks €20 million. €48 million was paid by the group of four banks, it is alleged, covered by hidden payments, fees, and earnings received from Milan in the derivative contracts. Milan paid the remaining €28 million via another derivative contract that cost Milan around €2 million. The public prosecutor alleged that the dealers misrepresented the transactions, unfairly enriching the banks by around €100 million.

According to city officials, the bankers had presented the transactions as being favorable to Milan, saving interest costs of €60 million. Officials did not grasp that interest costs would be higher if rates fell. Italian law only allows councils to restructure funding arrangements if it leaves them in a better position than before. The banks claimed that Milan was a financially sophisticated party and understood the transactions.

In 2009, around 600 Italian town councils disclosed losses from derivative transactions entered into in the belief that they were hedges. Around 700 German local authorities were also found to have similar problems. In Austria the state-owned railway made a loss of €420 million on derivatives, suing a bank alleging that risks had not been disclosed.

It is unclear whether Jefferson County, Harvard, and Milan had been fooled by bankers or were foolish in entering into transactions without understanding the risks. Michael Lewis’ warning that munis were a financial backwater was wrong. It was a place where bankers could make large profits.

Betting Your Hedge

Facing relentless pressure to meet earnings targets, companies relied increasingly on speculative trading to boost profits. Globalization reduced trade barriers, increased competition, and reduced profit margins. These narrow profit margins could be wiped out by fluctuations in volatile currency, interest rates, and commodity markets, sometimes overnight. Companies entered into complex derivatives, believing that they could get something for nothing. When things went wrong, the banks restructured the transaction, hiding the loss. All sides kept up the pretense that the transaction was a hedge until things went awry.

Sons of Gwalia (SoG) was the third largest gold mining company in Australia, producing 500,000 ounces each year. The company hedged, selling forward its gold production. Well-versed in digging holes in the ground to extract the precious metal, SoG dug itself a bigger hole by its hedging.12

When gold miners sell gold forward, guaranteeing a fixed price, they gain if the gold price falls but lose if the price goes up. If the gold price goes down, then there is a temptation to take profits, closing out the hedge which shows gains to boost current earnings. If the gold price goes up, then the company loses on the hedge, causing it to underperform unhedged competitors, who benefit from higher earnings from selling gold at higher prices. The mining company also owes the bank cash as collateral for losses on the hedge from the higher prices. The cash is required today, while the gold must be dug up and sold over time.

Mining companies can buy insurance against the gold price falling (put options) but the cost of insurance is expensive. To minimize cost, SoG bought insurance against lower gold prices (put options) but paid for them by selling insurance against higher gold prices (call options). If prices fell, then SoG was protected. If prices rose, SoG benefited until the gold price reached a certain level (the strike price of the call option). As prices rose above this level, SoG had to pay out under the insurance contracts that it had sold. It gained from selling the physical gold that it had produced at higher prices, but the payments under the sold insurance contracts would reduce its earnings.

Over time, SoG migrated to indexed gold put options (IGPOs), complex combinations of bought and sold insurance. The IGPOs entailed SoG selling between five and six times the insurance against the price going up (the call options) than it bought against the price going down (the put options). As the insured amount sold was larger than that bought, the IGPOs provided SoG with cash upfront, which was used to achieve higher prices for selling its gold or to hide losses on existing hedges.

SoG was committing to selling more and more gold if the price rose. By 2004, SoG had commitments to sell between 6 and 8 million ounces of gold against 3.1 million ounces of reserves. SoG did not have any gold but it did have a magnificent hedge. It was forced to file for bankruptcy with massive hedging losses.

TARDIS Trades

In 2008, exporters in many countries suffered large currency losses. The companies exported to Europe and North America, who paid in dollars that had to be converted into the exporter’s home currency—Japanese yen, South Korean won, Taiwanese dollar, Chinese renminbi, or the Indian rupee—to meet costs. If the dollar fell, then the exporters lost money as revenues fell in local currency terms.

In 2007, the dollar started to fall, causing panic amongst exporters with unhedged dollar revenues. Exporters sought help from financial engineers, who helped clients travel back in time on Dr Who’s TARDIS (Time And Relative Dimension(s) In Space) to when the dollar was stronger.

Assume that the Japanese exporter, with yen as its currency of operation, has $1 million of export revenue. It has budgeted on an exchange rate of $1 equal to ¥100, giving it ¥100 million of revenue. If the dollar falls to ¥90 (dollar depreciation or yen appreciation), then the exporter’s revenue falls to ¥90 million, a loss of ¥10 million (10 percent). The bank enters into a hedge where the exporter sells dollars at ¥95 (¥9.5 million in revenue), better than the current market rate of ¥90; a level at which the exports are still profitable to the company. It has the right to convert at ¥95 only if the yen does not strengthen above ¥85. At that level, the contract disappears, knocks out. If the yen weakens below ¥100 then the exporter must sell double the amount of dollars ($2 million) at ¥100 to the bank, the knock-in provision. This was known as the currency accumulator. Its relative, the target redemption forward, was similar but knocked out after the exporter made an agreed profit on the contract.

The exporter sold its dollars at better than market rates but risked large losses. It was selling double the amount of insurance on a stronger dollar than it was getting against a weaker dollar. If the yen strengthened significantly, the exporter was not hedged, precisely when it most needed to be hedged.

In early 2008, as U.S. investors repatriated overseas funds to cover losses, the dollar strengthened sharply, triggering the knock-in provision, which forced the exporter to sell double the dollars. If the exporters had dollars then they sold them at unfavorable rates. Some did not have sufficient dollars because exports had fallen, due to the global financial crisis, or had sold more dollars than they actually were contracted to receive.

As many as 50,000 companies in at least 12 countries, including Korea, Taiwan, China, Philippines, India, Eastern Europe, and Latin America, lost as much as $530 billion.13 Mexican cement producer Cemex revealed a loss of $500 million on derivatives. Controladora Comercial Mexicana SAB, Mexico’s third-largest supermarket operator, filed for bankruptcy after losing $1.1 billion from currency derivative deals.

In Hong Kong, Citic Pacific announced a $1.9 billion loss on derivative transactions involving Australian dollars, forcing its major shareholder—China’s biggest state-owned investment company Citic Group—to provide additional capital to ensure its survival. Citic claimed it was hedging its currency risks. Henry Fan, Citic Pacific’s managing director, told the Financial Times that he was “shocked” by the events: “I asked Leslie [Leslie Chang, Citic Pacific’s group finance director] how could this happen...he said he omitted to assess the downside risk.”14 It was a lack of “horse sense,” which as humorist Raymond Nash knew is: “what keeps horses from betting on what people will do.”

I Will Kill You Later

Dressed in school uniform and fishnet stockings, Christina Amphlett, vocalist with the Australian rock band The Divinyls, sang about the fine line separating pleasure and pain. For investors, the line between investment and speculation was finer still.

Concerned about stagnant incomes and inadequate retirement savings, individual investors chased higher returns. To meet forecast retirement benefits or insurance payouts, pension funds and institutional investors resorted to derivatives to enhance returns through leverage and taking on complex cocktails of risk.

The toxic currency structures of 2008 were copies of an earlier product—equity accumulators, known to traders as “I will kill you later” contracts. In a typical accumulator contract, the investor commits to purchase, or accumulate, a fixed number of shares per day at a pre-agreed price (the accumulator price) for a fixed period, typically 3–12 months. The accumulator price is set typically 10–20 percent below the market price of the shares at the time you enter the contract.

If the market price of the shares rises above a prespecified level (the knock-out price), the investor’s right to buy the shares knocks out, limiting upside gains. The knock-out price typically is set 5 percent above the market price of the shares at the time you enter the contract. If the market price remains below the knock-out price, the investor continues to accumulate the shares. If the market price falls below the accumulator price (typically a decline of more than 10–20 percent from the commencement of the contract), the investor must keep purchasing the shares, meaning unlimited downside risk. In most contracts, the number of shares the investor must purchase increases if the market price falls below the accumulator price. This step-up feature would occur typically two times, meaning that if the price fell below the accumulator price, the number of shares the investor purchased doubled.

In accumulator contracts, investors buy and sell a series of options that mature daily. The packaging of the product does not generally mention options, especially the fact that investors are selling options, a risky activity. Any disclosure is buried in the “risk section” of the Product Disclosure Statement. The print size and impenetrable legal prose mean that Sherlock Holmes would struggle to find the risks and a linguist would struggle to understand them.

Accumulators allow investors to buy shares at a price lower than the current price of the underlying shares. This is the byproduct of the option transactions. The options sold by investors are more expensive than the options the investor bought because the gain to the share buyer is limited while the potential losses are much larger. The difference in premiums creates the benefit. Dealers routinely benefit even more from selling accumulators, generally 4–5 percent of the total value of the contract upfront.

The investor gains where the share prices remain stable—between the knock-out price and the accumulator price. If the price goes up sharply then the accumulator knocks out, limiting the gain to the investor. If the price goes down sharply then the investor must purchase more shares, suffering losses because the purchase price is above market prices.

When the market fell in 2008, investors had to purchase larger number of shares under the step-up provision. Even where the share price had fallen but not below the accumulator price, the investor often lost because the current value of the contract had deteriorated as a result of changes in the volatility of underlying shares. Typically, investors put up around 10–25 percent of the value, agreeing to make margin calls where the value of the contract moved adversely. When the accumulator contracts showed money owing to the bank, the investor had to pledge more cash to cover the losses. If they could not come up with the cash then the contract was closed out, triggering losses for the investor. One dealer opined that: “a lot of investors have underestimated the cash flow commitment.”

First to Lose

In Asia, investors, often with limited education, purchased complex investments that offered slightly higher returns than bank deposits. Issued by a Cayman Islands’ SPV, Lehman Brothers’ Minibonds were marketed as simple bonds paying a high interest rate. In fact, they were complex, highly financially engineered derivatives, where the higher return required taking the risk that none of seven or eight companies would default or file for bankruptcy.

The SPV invested the money subscribed by investors in high-quality AAA-rated securities, initially investments in money market funds. The investments secured a credit derivative known as a first-to-default (FtD) swap. The investors received an annual fee that together with the interest on the money invested gave the investors the higher return. The investors agreed to make a contingent payment if any one of the identified firms defaulted. Under the FtD swap, the investors were exposed to all seven or eight entities, although the loss was limited to the first entity to default and the face value of the Minibonds.

Documents emphasized the remote risk of loss. The companies to which the investor was exposed were solid, well-known global institutions. While the sales literature highlighted the good credit rating (generally AA or A) of the individual companies, the investors were taking two risks—the likelihood of any of the firms in the FtD basket defaulting and the likelihood of one reference entity defaulting if another reference entity defaulted (default correlation).

Perfect default correlation (1) assumes that if any entity defaults then all other reference entities within the basket will default simultaneously. A zero default correlation (0) assumes that the risk of default of the reference entities is independent. If the default correlation within the basket is 1, then the FtD is equivalent to selling insurance on the most risky firm in the basket. If the default correlation is 0, then the FtD is equivalent to selling insurance on all the entities within the basket with a limit on the maximum loss. Assuming low or zero default correlation, the risk of any one entity within a basket of eight well-rated firms defaulting is significantly higher than for any single entity defaulting. A FtD basket based on investment grade companies may be equivalent to noninvestment grade credit risk.

Over time, instead of placing the investor’s money in money market funds, the cash was invested in CDOs and CDO2s, arranged and sold by Lehman, adding to the risk of the arrangements.

In Hong Kong, in accordance with local superstitions, no series of Minibonds were issued with the number 4, considered unlucky in Chinese culture. Advertisements and flyers prominently featured symbols of potency, luck or profit—tigers, rhinoceroses, and whales. Investors were enticed with prizes, including video cameras and flat-screen televisions.

Billions of Lehman Minibonds were sold to tens of thousands of investors in Asia, Australia, New Zealand, and Europe, especially in Switzerland, Germany, and Eastern Europe. Other banks emulated Lehman. As Pablo Picasso, the Spanish artist, observed: “Good artists copy, great artists steal.”

In October 2008, when Lehman filed for legal protection from its creditors under bankruptcy laws, investors suffered large unexpected losses. In most cases, none of the entities in the baskets had defaulted. Where Lehman was the purchaser of credit insurance from investors, the bankruptcy filing terminated the contract. Because of changes in market conditions, investors suffered mark-to-market or paper losses that had to be settled, requiring sale of the underlying investments. Where the money was invested in CDOs, the losses were large.

The documentation included a flip clause, providing that the underlying collateral should be applied firstly to amounts owed to Lehman and then to the amounts owed to investors. If Lehman defaulted, then there was a change in priority. Lehman would rank behind investors in the distribution of underlying proceeds.

When Lehman applied for bankruptcy protection, it triggered the change in priority of payment. However, on November 25, 2008 Lehman’s legal counsel notified investors that the flip clause breached the U.S. Bankruptcy Code and was unenforceable. The alteration of priority on default was found to be enforceable as a matter of English insolvency law, but unenforceable as a matter of U.S. Bankruptcy Law. If the U.S. position is upheld by appellate courts, the investor’s loss will be exaggerated.

In the Minibonds, initially bankers and, after the problems, lawyers, and insolvency practitioners cleaned up. Always first to lose, the investors were just completely cleaned out.

Toxic Municipal Siblings

Located around 125 miles (200 kilometers) south of the Arctic Circle in Norway, Narvik’s ice-free harbor and proximity to the iron ore mines in Sweden make the town strategically important. In the Second World War the Germans tried to gain control of the town to access the ore, triggering a naval battle. The wrecks of German, Norwegian, and British ships in the Fjords and the town’s history are a tourist attraction.

In November 2007 Narvik, together with other Norwegian investors, lost money in investments involving American municipalities manufactured by CitiGroup and sold by Terra Securities, a Norwegian securities firm.

In 2004, using a loophole in their regulations, Narvik and other Norwegian municipalities—all large producers of hydroelectricity—borrowed using future energy revenue as collateral. The money raised was invested in complex securities offering high returns, such as highly leveraged securities linked to American municipal TOBs (tender option bonds), a form of ARS. The Norwegians received between 0.5 and 3 percent per annum more than they would receive on bank deposits but risked losing their entire investment.

In 2007 and 2008, as the problems in the U.S. municipal debt markets emerged, the investments linked to the underlying muni bonds lost value, causing large losses. Narvik was at the other end of the fuse lit by Jefferson County across the Atlantic. The investments were a quarter of the Narvik annual budget. To cover the losses, the town took out a long-term loan to be paid back by cutting back on civic services, such as childcare, health services, and cultural institutions. In late 2007, Narvik missed making the payroll for municipal workers. Narvik’s museum, chronicling its war history, was a victim of the crisis.

Playing Swaps and Robbers

Derivatives were frequently part of elaborate arrangements to avoid regulations. Fiat S.p.A. (Fabbrica Italiana Automobili Torino or Italian Automobile Factory of Turin) is an Italian carmaker, created in 1899 by a group of investors led by Giovanni Agnelli. In the early 2000s, Fiat faced financial and operating difficulties, losing over €8 billion. Following restructuring, Fiat, now led by CEO Sergio Marchionne, recovered, making a profit of €1 billion in 2005.

To survive, Fiat borrowed €3 billion through a convertible bond, where the banks could exchange the loan into Fiat shares. On April 26, 2005 Fiat announced that the loan would be converted into Fiat shares on 20 September 2005, giving the banks 24 percent of Fiat and diluting the Agnelli family’s interest, held through IFIL Investments (IFIL), from 30 percent to 23 percent.

To maintain control of Fiat, IFIL needed to buy shares in Fiat. If it purchased shares in Fiat before 20 September 2005, pushing its ownership interest over 30 percent, then under Italian law IFIL would be forced to launch a takeover bid for the entire company at a premium to the market price. Instead, IFIL used derivatives—total return swaps on shares or equity swaps—to preserve control of Fiat.

On April 26, 2005 Exor, a private company 70-per-cent-owned by the Agnelli family, entered into a swap with Merrill Lynch. Under the terms of the swap, Merrill would pay Exor the total return on 90 million Fiat shares (around 7 percent of the share capital), worth €495 million at €5.50 per Fiat share, the price at which Merrill purchased Fiat shares in the market.

Under the swap, Exor assumed the full economic risk of the shares, receiving any increase in the value of Fiat shares above €5.50 and paying Merrill any decrease below €5.50. Exor covered Merrill’s funding cost on the shares. The swap was to be settled at maturity in cash, with no delivery of Fiat shares, avoiding disclosure to Italian regulators.

On September 15, 2005 Exor and Merrill amended the original swap, allowing settlement by physical delivery of the shares. At maturity, Exor would receive 90 million Fiat shares in return for paying €495 million to Merrill (equivalent to the agreed price of €5.50 per share). The conversion was disclosed as required under Italian security laws. In late September, after the bank loan was converted, IFIL purchased the shares acquired by Exor under the swap from Merrill at €6.50 per share, giving Exor a profit on the sale of the shares.

The swap allowed IFIL to maintain its shareholding in Fiat at 30 percent. The Agnelli family through Exor acquired the required shares without triggering a full takeover of Fiat, as IFIL never exceeded the 30 percent threshold. The Agnelli family acquired the required 7 percent of Fiat at favorable prices, €5.50 per share against €7 per share in late September 2005. By early 2007, Fiat shares were trading above €17 per share.

In February 2007, in a civil case, the Italian regulators (Consob) fined IFIL, a related company and directors €16 million. The chairman of IFIL and two senior officers of the company were suspended from holding posts in public companies for between 2 and 6 months. IFIL appealed against the decision. Italian regulators also fined two Merrill Lynch bankers €250,000 for failing to disclose that the firm had equity swaps that entitled it to more than 5 percent of Fiat.

In 2010, luxury goods firm LVMH made a bid for control of Hermès, surprising the descendants of Thierry Hermès, a saddle maker who founded the company in 1837. Just like of Fiat, LVMH built the stake through cash-settled equity swaps with three banks in 2008, when the luxury industry was in crisis. The derivative contracts allowed LVMH to avoid disclosure requirements, producing a nice profit for LVMH when Hermès shares rose.

The Greek Job

In the 1990s, Japanese companies and investors pioneered the use of derivatives to hide losses, a practice called tobashi (from the Japanese verb tobasu meaning “to make fly away”). Subsequently, a number of European countries used derivatives to disguise their borrowings.

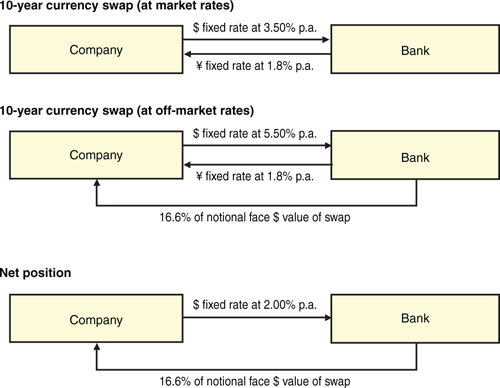

Derivatives, such as interest rate and currency swaps, are normally used to alter the nature and currency of cash flows on assets or borrowings. Transactions involve exchanging one stream of payments for another. At commencement, if the contract is priced at current market rates, then the value of the two sets of cash flows should be roughly equal.

Using artificial or “off-market” interest or currency rates, it is possible to create differences in value between payments and receipts. If the value of future payments is higher than future receipts, then the party making the future payments receives an up-front amount reflecting the positive value of the contract. In effect, the participant receives a payment today that is repaid by the higher than market payments in the future—identical to a loan. Figure 13.3 sets out the strategy using a simple currency swap.

Figure 13.3. Off-market currency swap

In 2008, Greece was found to have entered into a series of transactions with Goldman Sachs to disguise its debt. Earlier, academic Gustavo Piga identified an unnamed European country, generally assumed to be Italy, using derivatives to provide similar window dressing.

In December 1996, Italy allegedly used a currency swap against an existing ¥200 billion bond ($1.6 billion) to lock in profits from the depreciation of the yen. Done at nonmarket rates, the swap was really a loan where Italy accepted an unfavorable exchange rate and received cash in return. The payments were used to reduce Italy’s deficit, helping meet the European Union target of less than 3 percent of GDP under the EU Maastricht Treaty.

The Greek transactions were similar off-market cross-currency swaps linked to the country’s foreign currency debt. The swaps were for a notional principal of approximately $10 billion, with maturities between 15 and 20 years. The cash received may have reduced the country’s debt/GDP ratio from 107 percent in 2001 to 104.9 percent in 2002 and lowered interest payments from 7.4 percent in 2001 to 6.4 percent in 2002. The future payment obligations under the swaps were not reported as a future liability for Greece.

Dealers made money by helping clients hedge or take on more risk using derivatives. Clients also paid dealers handsomely for structures that took advantage of regulatory loopholes. Goldman Sachs allegedly made around $300 million from the Greek job.

Madman’s Games

Much of the financial innovation was designed to conceal risk or leverage, obfuscate investors, and reduce transparency. Complexity was used to make products difficult to understand and analyze, allowing them to be priced inefficiently to produce excessive profits for traders. After the Narvik problems surfaced, the CEO of Terra Securities admitted that he did not know how the product worked. When the original CitiGroup prospectus for the product was translated from English to Norwegian, the original risk disclosures appeared to have been omitted. As Warren Buffett once remarked, derivative contracts are “limited only by the imagination of man—or, sometimes, it seems, madmen.”15

Harvard Professor Elizabeth Warren noted that in the pharmaceutical industry innovators once earned large profits by skillfully marketing quack cures and ineffective products, exploiting the customers’ poor understanding of products. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration developed disclosure rules, helping foster safer, effective drugs and treatments. Complex derivative products, incomprehensible structures, and sharp sales practices are relatively unregulated. Complexity, she argued, is the handmaiden of deception.16