22. Financial Gravity

In 2007, everyone discovered what Joseph Conrad knew: “[a civilized life is] a dangerous walk on a thin crust of barely cooled lava which at any moment might break and let the unwary sink into fiery depths.”1 The end arrived unexpectedly, reflecting author Alexander Pope’s description of the collapse of the 1720 South Sea Bubble: “Most people thought it wou’d come but no man prepar’d for it; no man consider’d it would come like a thief in the night, exactly as it happens in the case of death.”2

Air Pockets

As interest rates increased from 1 percent to 5.25 percent per annum, reflecting higher oil and food prices, U.S. house prices stalled and then fell. Subprime mortgages predicated on low rates, rising house prices and the ability to refinance on favorable terms defaulted. Losses were significant but not huge. But mortgage defaults also triggered paper losses on highly rated securities used as collateral for borrowing. Borrowers sold everything to meet the need for cash to margin calls, forcing down prices setting off new margin calls, causing losses to radiate through the financial system.

In 1929, JP Morgan’s Thomas Lamont had tried to calm markets: “There has been a little distress selling.... Air holes caused by a technical condition...the situation was ‘susceptible of betterment.’”3 As the stock market fell, John D. Rockefeller issued a statement: “Believing that the fundamental conditions of the country are sound...my son and I have for some time been purchasing sound common stocks.” Actor Eddie Cantor, who lost a substantial sum in the collapse of Goldman Sachs Trading Corporation, replied: “Sure, who else had any money left?” Cantor created a skit where a stooge walks out on stage violently squeezing a lemon. Cantor asks: “Who are you?” The stooge replies: “I’m the margin clerk for Goldman Sachs.”4

Heading for the exit at the same time, traders learned that everybody owned the same securities, all financed with borrowed money. Liquidity evaporated. Nobody had any idea what anything was worth, marking them down aggressively and fearing the worst. Markets were awash with rumors. As the Roman poet Virgil wrote in the Aeneid: “Of all the ills there are, rumour is the swiftest. She thrives on movement and gathers strength as she goes.” Everybody feared that everyone except them was insolvent.

On August 3, 2007, on CNBC, a more out-of-control than usual Jim Cramer made the panic palpable: “Bernanke is being an academic. He has no idea how bad it is out there. [He’s] nuts! They’re nuts! They know nothing.” Earlier on April 20, 2007, speaking on CBS Marketwatch, Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson had been upbeat, the U.S. economy was “robust” and “very healthy,” and “the housing market is at or near the bottom.” Here was a man who had jumped off a 50-story building without a parachute saying that it was all plain sailing so far, as he passed the 40th floor.

Mass Extinction

In June 2007, Damien Hirst tried to sell a life-size platinum cast of a human skull, encrusted with £15-million-worth of 8,601 pave-set industrial diamonds, weighing 1,100 carats, including a 52.4-carat pink diamond in the centre of the forehead valued at £4 million. Entitled For the Love of God, it was a memento mori, in Latin “remember you must die.” Betting on demand from wealthy financiers, the work was offered for sale at £50 million as part of Hirst’s Beyond Belief show. In September 2007 For the Love of God was “sold” to Hirst and some investors for full price, for later “resale.”

The sale of The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living marked the last phase of the irresistible rise of markets. The failure of For the Love of God to sell marked its zenith as clearly as any economic marker.

In July 2007, Bear Stearns injected $1.6 billion into one of its hedge funds. On 7, August 2007, on the brink of collapse due to investments in mortgage-backed securities including the ill-fated Goldman Sachs CDO Abacus, German lender IKB Deutsche Industriebank was rescued. On August 9, 2007 BNP Paribas, a French bank, suspended redemptions on some of its investment funds. On Thursday, September 13, 2007 the run on Northern Rock forced the UK government to guarantee all existing bank deposits to stop the run. In March 2008, JP Morgan purchased Bear Stearns for a price lower than that paid by the LA Galaxy for the footballer David Beckham.

In September 2008, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac were nationalized. In desperate shotgun marriages, Merrill Lynch merged with Bank of America, and Wachovia merged with California-based Wells Fargo. Washington Mutual failed. On September 15, 2008 Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy protection in the world’s largest corporate failure, with debts of $768 billion and assets worth $639 billion. A few days later the U.S. government took a majority stake in AIG to stave off failure.

In Cat’s Cradle, Kurt Vonnegut wrote about ice-nine, a hypothetical substance which, if brought into contact with liquid water, freezes. Ice-nine had been dropped into the world’s money markets, freezing up the global financial system. Investors pulled money out of banks and money market funds. They were following Tennessee Williams’ advice for survival: “We have to distrust each other. It is our only defense against betrayal.”

Some 65 million years ago, the impact of an asteroid in Mexico, equivalent to an explosion of 100 million tons of TNT, created the Chicxulub crater, 120 miles (180 kilometers) in diameter. 300,000 years later (an eye blink in geological time), a second much larger celestial object, named Shiva, the Indian God of destruction, hit India with a force estimated at 100 times that of the Chicxulub asteroid, creating a 310-mile (500-kilometre) crater. Debris ejected into the atmosphere shut out the sun, creating a nuclear winter that prevented photosynthesis by plants, slowly starving most life and leading to the extinction of millions of species, including dinosaurs.

Something similar had happened to the global economy. A lack of money slowly caused normal economic activity to stop. Money was the oil lubricating the economy. Now the oil was leaking out via a large crack, and the moving parts were seizing up.

In Indian mythology, Brahma is the creator of the world. In his next incarnation or avatar as Vishnu, the preserver, he sustains the world. In his final transformation, Vishnu becomes Shiva. At the Trinity test site, watching the power released by the explosion of the world’s first atomic bomb, Robert Oppenheimer resorted to the sacred text of the Bhagavad Gita: “I am become Death, Shiva, destroyer of worlds.”5 Money had created and preserved modern economies. Now, it unleashed its destructive power, ironically by its absence.

ER

Panicked market participants searched for nonexistent exits, confirming Lloyd George’s observation: “Financiers in a fright do not make a heroic picture.”

The Fed resorted to a tried and tested solution, cutting interest rates from 5.25 percent to 0.00 percent. An alphabet soup of facilities was hastily assembled, desperately pumping money into the economy—PCF (primary credit facility); TAF (term auction facility); TSLP (term securities lending facility); and PDCF (primary dealer credit facility). Ultimately, the Fed resorted to printing money, known as quantitative easing. Wanting to hug the Fed chairman, Jim Cramer thought that Bernanke “got it.”

Bernanke once boasted that dropping money from a helicopter would stop such a crisis. Central banks assumed that price falls reflected a temporary shortage of cash and confidence. Elizabeth Warren, chair of the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP), Oversight Panel Report, questioned the approach:

One key assumption...is [US Treasury’s] belief that...the decline in asset values...is in large part the product of temporary liquidity constraints...it is possible that Treasury’s approach fails to acknowledge the depth of the current downturn and the degree to which the low valuation of troubled assets accurately reflects their worth.6

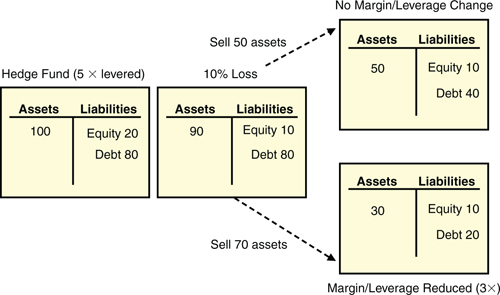

Figure 22.1 shows how falling prices affect values of assets financed with debt. Assume an investor with $20 of their own money—equity—is allowed to leverage five times, allowing the purchase of $100 of assets (funded with $20 of equity and $80 of debt). If the asset falls 10 percent in price to $90, then the investor’s leverage increases to 9 times ($10 of capital (the original amount less the loss) and $80 of debt supporting $90 of assets). If the permitted leverage stays constant at 5 times then the investor must sell $50 of assets (50 percent) to reduce borrowing—$10 of capital and $40 of debt funding $50 of assets. If lenders reduce leverage to 3 times, then the investor must then sell $70 of assets (70 percent) with $10 of capital and $20 of debt funding $30 of assets.

Figure 22.1. Effect of falling prices on assets purchased with debt

Reduction of debt requires liquid markets and buyers with money to purchase the assets. In the absence of buyers, prices fell as the system reduced debt. In January 2008, George Soros observed:

Boom-bust processes usually revolve around credit and always involve a bias or misconception. This is usually a failure to recognize a reflexive, circular connection between the willingness to lend and the value of the collateral. Ease of credit generates demand that pushes up the value of property, which in turn increases the amount of credit available.7

The process was now working in reverse.

This Is Not a Seminar!

By September 2008, images of people unable to draw money out of ATMs and banks closing down destroying people’s life savings did not seem farfetched. Kent and Edgar’s apocalyptic vision in Shakespeare’s King Lear now haunted the world: “Is this the promised end? Or image of that horror?”

The FOMC (the Federal Open Market Committee) was openly derided as the “Open Mouth Committee.” Realizing the need for more radical action, U.S. Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson briefed President George Bush, describing the conditions as “cardiac arrest.” The President grasped the problem: “This sucker could go down.”8 The satirical magazine Onion parsed it as “Bush calls for panic.”

On September 18, 2008 Paulson and Bernanke proposed a $700 billion emergency bailout. Bernanke told skeptical legislators: “If we don’t do this, we may not have an economy on Monday.”9 Other countries followed with bailout packages and measures to stimulate the economy. The United States, UK, and Europe committed $14 trillion, 25 percent of global GDP, equivalent to $7,000 for every man, woman, and child.

Paulson believed the package would not be needed: “If you’ve got a bazooka, and people know you’ve got it, you may not have to take it out.”10 The former Goldman Sachs CEO was unable to move beyond banking’s deal culture. Bungled initiatives followed half-baked ideas. Finally, the U.S. government was forced to take significant stakes in major banks, guaranteeing debt and deposits of the banks. The UK government also partially nationalized major banks. Other countries throughout the world implemented similar measures.

The concern was that another big financial institution would fail, affecting firms that they had dealings with and triggering a collapse of the global financial system. In 1902, Paul Warburg warned James Stillman, president of National City Bank: “Your bank is so big and powerful, Mr. Stillman, that when the next panic comes, you may wish your responsibilities were smaller.”11 Asked about government assistance to firms considered too big to fail, George Schultz, secretary of the Treasury under President Nixon, snapped: “If they are too big to fail, make them smaller.”12 But now big financial institutions were all TBTF—“too big to fail.” Governments everywhere rushed to prop them up.

Dubbed WIT (whatever it takes) by British Prime Minister Gordon Brown, or WIN (whatever is necessary) by U.S. President Obama, the actions were designed to stabilize the financial system and maintain economic growth. Bank of England Governor Mervyn King summed up the strategy: “The package of measures announced yesterday by the Chancellor are not designed to protect the banks as such. They are designed to protect the economy from the banks.”13 Upon announcement of the $700 billion TARP bailout package, Republican Senator Jim Bunning quipped: “When I picked up my newspaper yesterday...I thought I woke up in France. But no, it turned out it was socialism here in the United States.”14 The Chinese joked that the United States was adopting Chinese socialism with American characteristics.

In good times, bankers are capitalists. During crises, bankers are socialists. In every crisis, policy makers argue that people’s life savings and pension entitlements are at risk if the system is not bailed out. No one asks who put them at risk in the first place. Bankers’ excuses are of someone having murdered their parents seeking clemency on the grounds that he is an orphan.

The social activist Naomi Klein termed it disaster capitalism.15 Having unknowingly underwritten a system allowing banks to generate vast private profits, ordinary men and women were forced to bear the cost of bailing out banks. As his friend Dink tells author Joe Bageant: “Sounds like a piss-poor solution to me, cause they’re just throwing money we ain’t got at the big dogs who already got plenty. But hell what do I know?”16

On CBS’s 60 Minutes, Bernanke defended the policy: “I come from Main Street. That’s my background. I’ve never been on Wall Street. And I care about Wall Street for one reason and one reason only: because what happens on Wall Street matters to Main Street.” As Nick, in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, observes about Tom and Daisy, scions of the monied classes: “It was all very careless and confused...they smashed up things and creatures and then retreated back into their money or their vast carelessness, or whatever it was that kept them together, and let other people clean up the mess.”17

ICU

Banks choked on bad loans. In a phenomenon dubbed IAG, involuntary asset growth, loans hidden in the shadow banking system came back on to the bank’s own books. No one knew how to do any of this. One SIV manager joked: “I need to read the instruction manual.”

Jim Cramer called banks’ financial statements “works of fiction.” To survive, banks needed capital and money. No one thinks that they are going to need extra capital or money. If they need it, then they think they can get it at a price. If you wait until you need it, you can’t get it at any price. Financial institutions rummaged in the backs of sofas looking for spare change to stay afloat.

The sense of Schadenfreude, Masters of the Universe receiving their comeuppance, evaporated. The financial crisis spread quickly to the real economy. In the United States, more than 8 million jobs were lost, with unemployment rising to 10 percent (over 15 million workers), the highest level since the early 1980s. The State of Ohio received 80,000 calls per day for unemployment claims (versus a normal 7,500 per day). Ohio hired temporary staff to handle the volumes of unemployment claims. Including people not seeking work because none was available or forced to work part-time, real unemployment in the United States hovered around 16–18 percent of the workforce. In Europe, unemployment rose above 10 percent.

Global trade volumes decreased 12 percent, the first fall in 25 years. In the third quarter of 2007, Sweden’s Volvo AB, the second largest global truck maker, received 41,970 European orders. In the same quarter of 2008 the firm received orders for 155 vehicles, a decline of 99.63 percent. As exports fell, 20 million Chinese workers in the southern province of Guangzhou were thrown out of work. As Karl Mayer von Rothschild noted in 1875 in relation to a different crisis: “The whole world has become a city.”18

By December 2008, the Baltic Dry Index, a measure of shipping costs, had fallen more than 90 percent from its May 2008 peak of 11,793. The cost of sending a 40-foot (12-metre) steel container from China to the UK fell from $1,400 to $150 before rebounding to $300. By late 2008, a tenth of the vessels that transport the world’s trade were idle. In the Strait of Malacca near Singapore, a vast ghost fleet of cargo vessels sat idle at anchor.

Bellwether GE missed earning forecasts, then lowered earnings guidance. As its stock price fell, former CEO Jack Welch threatened to get a gun and shoot his successor Jeff Immelt. Warren Buffett bought $3 billion in GE preferred stock, paying an annual dividend of 10 percent with options to purchase $3 billion of common stock at $22.25. The 10 percent rate was what junk bond companies, not a AAA company like GE, would expect to pay. GE also sold another $12 billion of additional shares at $22.25 to the public.

Focused on beating short-term earnings goals, over the previous three years GE had spent $30 billion on share buybacks. Now needing capital, GE sold shares at low prices, having bought them back at higher prices.

Chrysler was bought out by Fiat. Bailed out by the government, GM (nicknamed “Government Motors”) filed for a prepackaged bankruptcy to try to salvage a viable business. Larry Flynt (founder of Hustler) and Joe Francis (creator of Girls Gone Wild) sought $5 billion to bailout the adult entertainment industry where revenues were falling: “Americans can do without cars...but they cannot do without sex.”19

Country for Sale

As the boom in Ireland got “boomier,” household debt increased to 160 percent of GDP, up from 60 percent. Irish banks lent aggressively to property developers in an unprecedented real estate boom. Having doubled in price in a few years, a modest family home in Dublin cost the same as one in Beverly Hills. A three-bedroom penthouse in the Elysian, the tallest building in Ireland, complete with Porsche SE taps and views over Cork, cost €1.8 million ($2.6 million).

Intoxicated at the success of the “Celtic tiger” and the country’s double-digit growth, the Irish splashed out, behaving like “a poor person who had won the lottery.” As novelist Anne Enright expressed it: “We’re very narcisstic...[believing] our boom was better than anyone else’s.”20

Now, house prices fell by 50 percent and the cranes that dotted Dublin’s skyline stood idle. The Irish banking system collapsed under the weight of bad loans, unable to raise money. In September 2008, Ireland was the first major nation forced to guarantee the debts of its banks totaling €400 billion, nearly three times Ireland’s annual GDP.

The economy contracted by 20 percent with unemployment expected to reach 15–20 percent. Ireland spent more than 30 percent of its GDP to bailout its banks. Government debt rose sharply from the low 25 percent of GDP it reached during the good times to more than 100 percent of GDP. Businesses, like Waterford Wedgwood, owner of the luxury crystal and china brands, downsized or closed down. The downturn exposed the problems of corruption and close associations between business people, bankers and politicians.

Lack of prospects revived a historical trend of Irish emigration to the United States, Canada, or Australia. This reversed a trend during the boom years when many émigrés returned to Ireland and immigrants sought employment in the country’s construction boom. The tired joke was that the difference between Iceland and Ireland was a “c.”

When their country collapsed earlier, Icelanders overseas could not draw money out of ATMs. Individuals, local government and charities, who had deposited their savings at high-interest rates with Icelandic banks in the UK, like Icesave, could not access their money. Iceland’s government took over the largest banks as they collapsed with debts equal to about 12 times the total economy. In an attempt to protect British depositors, the UK used 2001 antiterrorism laws to freeze the British assets of a failing Icelandic bank. Iceland was listed alongside Al Qaeda, Sudan, and North Korea.

Overnight, the Icelandic economy and the Icelandic currency, krona or kronur, collapsed. Reopening after a three-day suspension of trading, Iceland’s stock market fell 77 percent. Depositors lost their savings or found them much reduced in value. The repayments on borrowings in low-interest foreign currencies, like euro and Swiss franc, increased to unsustainable levels. As much of Iceland’s requirements must be imported, costs skyrocketed.

Foreigners left Iceland. More than one-third of Icelanders contemplated emigrating. A proud, independent country had been brought to its knees by the crisis. The new government approached the IMF, seeking a €4 billion loan (over €13,000 for each Icelander) to shore up the economy.

Iceland was for sale on eBay: “Located in the mid-Atlantic ridge of the North Atlantic Ocean, Iceland will provide the winning bidder with a habitable environment, Icelandic horses, and admittedly a somewhat sketchy financial situation.” You had to pick it up yourself. Bjork, Iceland’s famous pop star, and Sigur Ros, a rock band, were not included. Buyers inquired whether COD (cash on delivery) was acceptable, joking that their payments might be frozen.

Iceland’s Kaupthing Bank, Landsbanki, Glitnir and the Central Bank were awarded the Ig Nobel Economics Prize, recognizing their work on how small banks could be transformed rapidly into big banks and vice versa. The Ig Nobel Mathematics Prize went to Gideon Gono, governor of Zimbabwe’s Reserve Bank, for printing bank notes with denominations ranging from 1 cent to 1 hundred trillion dollars to help Zimbabweans cope with hyperinflation.

In 2008, a banker was transferred from New York to London. To finance a Range Rover, he sold his modest shareholding in his employer, a bank. The banker was subsequently transferred to Dubai. When selling his Range Rover, he suffered a loss of 50 percent of the price he paid 6 months ago. The proceeds from the sale of the car (despite the 50 percent loss) would have allowed the banker to purchase five times the number of bank shares he originally sold to finance the car. In Iceland, there was an oversupply of Range Rovers, now known as “Game Overs.”

Crying Games

Nicolas Sarkozy, president of France, pronounced laissez faire capitalism dead: “C’est fini!” Wang Qishan, vice-premier of China, tartly observed: “The teachers now have some problems.”21 Luiz Inácio “Lula” da Silva, president of Brazil, blamed the global financial crisis on “the irrational behavior of white people with blue eyes, who before the crisis appeared to know everything, but are now showing that they know nothing.”22 He termed it “an eminently American crisis” caused by people trying to make a lot of “third-class money.”

Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams called traders who cashed in on falling prices “bank robbers and asset strippers.” Archbishop of York John Sentamu thundered: “We have all gone to this temple called money. We have all worshipped at it. No one is guiltless.” The Church had lent stock to short sellers, sold a mortgage portfolio and bought shares in the biggest listed hedge fund.23

Politicians blamed bankers. Bankers blamed the borrowers who borrowed excessively. Borrowers blamed bankers for forcing them to borrow, stagnant income levels, job insecurity, the high cost of living and poverty. Reborn Keynesians blamed free-market economists, who argued that the problem was not too little regulation but too much interference in markets. Familiar with the demon drink, George Bush blamed alcohol, claiming that bankers got drunk.

Vikram Pandit singled out short sellers as the cause of Citi’s problems. Bad loans, excessive investments in structured securities, inadequate capital relative to risk and a host of other failures were irrelevant. Blaming the messenger of bad news, short selling was banned or restricted in many countries. The debate was informed by Mark Twain’s observation that: “I am not one of those who in expressing opinions confine themselves to facts.”

In South Korea an online blogger, using the pseudonym Minerva, the Roman goddess of wisdom, predicted the imminent collapse of Lehman Brothers and made dire forecasts about the South Korean currency (the won), his site registering 40 million hits. When the won fell 26 percent, an unimpressed Korean government arrested the celebrity blogger, known to netizens as “the Internet Economic President.”

Newtonian Economics

In 2003, Robert Lucas, a Nobel-Prize-winning economist, declared: “macroeconomics...has succeeded. Its central problem of depression-prevention has been solved, for all practical purposes, and has been solved for many decades.”24 Gordon Brown boasted that under New Labour’s stewardship the boom-bust cycles of the UK economy had been banished. As the global economy slid into crisis, economists and analysts contemplated the D-word that dare not say its name—depression. Terrified of losing money on their vast holdings of U.S. dollars, the Chinese resuscitated Keynes’ proposal for a global reserve currency—the bancor.

Dead economists were resurrected in support of political positions. Upsurge in government intervention and massive spending to stimulate demand marked the return of Keynesian economics. In 1996 Lucas told a journalist: “One cannot find good under-forty economists who identify themselves as Keynesian...people don’t take Keynesian theorizing seriously anymore: the audience start to whisper and giggle to one another.”25 After a period when free markets, the Chicago School and Friedman’s ideas dominated, Keynes was back in vogue. Minsky, too, had a good crisis.

Keynes is always the economist for a crisis, providing desperate governments with the intellectual basis for massive and dramatic fiscal stimulus. Benn Steil, of the Council on Foreign Relations, succinctly explained the resurrection: “when the facts are on our side, we pound the facts; when theory is on our side, we pound theory; and when neither the facts nor theory are on our side, we pound Keynes.”26 Just as there are no atheists under bombardment, Robert Lucas joked that “everyone is a Keynesian in a foxhole.”27

As Keynes himself observed:

The ideas of economists and political philosophers, both when they are right and when they are wrong, are more powerful than is commonly understood. Indeed the world is ruled by little else. Practical men, who believe themselves to be exempt from any intellectual influences, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist. Madmen in authority, who hear voices in the air, are distilling their frenzy from some academic scribbler of a few years back.28

In 1929, investment analyst Roger Babson anticipated the stock market crash. In his pamphlet Gravity—Our Enemy Number One, Babson argued that gravity was an evil force.29 In the credit boom, prices rose, defying gravity. Financial gravity had reasserted its malevolent power.