Epilogue: Nemesis

Nemesis—in classical Greek mythology, the goddess of retribution and downfall.

Marginal

“What the f**k do you think you are doing!” Uncertain whether the question was rhetorical, I replied: “Good to hear from you, Mailer.” “Are you acting for JR against us?” As it happens, I am acting for the administrator appointed by the fund’s investors. Earlier, I accompanied the administrators, the insolvency firm of Check & Charge Partners, to a meeting at Mailer’s employer. JR’s Leveraged Structured Credit Fund (LSCF) owns several billion AAA and AA-rated MBSs, CDOs, and CDO2s, funded 95 percent by money borrowed from Mailer’s bank.

The market value of the securities had fallen 50 percent, well below the level of debt. The bank wanted LSCF to lodge $1,100 million additional collateral to secure the loan. LSCF didn’t have the money. Alarmed, the fund’s major investor called in Check & Charge, who called me. Ralph Smitz, one of the principals of JR Capital who manage the hedge fund, surprisingly recommended me. I had always thought he disliked me. Just in case, I secured an upfront payment, making sure, at least, I would get paid.

Dick Gormless, the senior insolvency partner, instructs me to do the “heavy hitting.” Asked what he wants, he takes off his glasses, rubs his eyes several times, and mutters: “Live to fight another day.” The meeting begins badly and gets worse. We front the money or the bank seizes the securities and sells them, wiping out the LSCF’s investors. The agreement enables them to do what they please—determine the value of the securities, or change the level of collateral at any time.

“I think you’re right! Those securities are worth at most, say, 10 cents, 20 cents in the dollar.” My agreement with our torturers catches the bank and Gormless by surprise. “You agree?” O’Connor, vice-president in charge of risk management, asks cautiously. “Absolutely!” There is no turning back.

“First, we understand that your bank is holding around $20 to $30 billion of the same paper. We also understand that you are valuing your holdings at 90 percent of face value or even higher. You obviously think that there will be minimal losses if you hold them till they mature. Unfortunately, as administrators, we must advise the court and also bank regulators of the discrepancy between where you are valuing us and where you are valuing what you are holding. Second, if you seize the collateral, it will go on to your balance sheet. You will have to mark them down further. Third....”

“How do you know our holdings and marks?” Rogers, the managing director in charge of prime brokerage, interrupts. “Third,” I continue, ignoring him, “we will file for bankruptcy. Any collateral we place with you gives you unfair preference over other creditors. The administrators are duty bound to challenge this in court. Fourth, we believe that your bank misrepresented the details of the securities to us. The collateral risk was not properly explained....”

“Blackmail.” O’Connor sounds shocked. I smile: “You know these issues are fascinating ones. They would be interesting to test in court. There is the issue of valuations, your models. The regulators, I’m sure, would be very interested. So would all your other clients, I imagine.” I pause. “Can you give us a few minutes alone,” Rogers finally speaks. The bank team leaves the room. Gormless is about to say something but doesn’t.

Returning after 20 minutes, Rogers reopens hostilities: “What do you want, really?” “Time. 30 days. We can arrange for a new capital injection into the fund. We need you to extend the maturity of your financing. Renegotiate the terms.” Rogers thinks about it. “I can’t do that on my own. Can I give you our answer this afternoon?” Straight after lunch, Gormless rings me to confirm that the bank has given us 10 days.

I spend the rest of the day at another bank, advising them to increase the level of collateral on positions with hedge funds and other banks to ensure sufficient cover in case things continue to get worse. I help tweak their valuation models, ensuring low prices that increase the margin calls and the cash the other side must pay up. In finance, flexibility and split personalities are important.

Widows and Orphans

Morrison Lucre and I are reunited for the first time since the Asian crisis of 1997/8. Crises are kind to scavengers like me.

Lucre & Lucre have merged with a large global legal practice—the establishment American firm of Tink Notting. “Sad. Family started the firm in the eighteenth century,” Morrison mused. “You won’t believe this. They sent in a management consultant!” Morrison is indignant. “What would they know about the law?” He rails. Morrison has romantic notions about justice.

I provide expert evidence in disputes between banks and their clients. I will kill you later products have killed several European and Asian investors sooner than expected. Lehman Brothers Principal Guaranteed equity notes guaranteed only large losses. The Lehman Minibonds generated minuscule returns and maximum losses. Fund managers purchased products because other funds managers were buying them. Individuals bought them for higher interest, believing the investments were safe. Companies bought them thinking they could make money easily because their real business was unprofitable.

I study prospectuses and voluminous documentation. The “pulp fiction” claims and counterclaims are depressing. Clients bleat about being egregiously misled about risks and unsuitable products. Sophisticated dealers have taken advantage of them. Dealers claim that the clients are sophisticated, understood the risks, and entered the transactions while fully clothed and conscious. Banks rely on documents—PDS (product disclosure statement) explaining the risks; RDS (risk disclosure statement) signed by clients stating that they understood the risks; NRA (non-reliance agreement) stating that the client was not relying on the bank to explain the risks.

Innocents who have lost their life savings cannot afford legal help. Morrison and I help the deserving ones that can afford us. An Oriental dowager, worth several hundred million dollars, claims to have invested under the influence of her prescription drugs and a charming banker. Having completed several hundred transactions, she is hardly the proverbial widow and orphan, with no experience of such dealings. When we point this out, the old woman frostily advises us that she is a widow and her parents are dead.

Bank claims that the risks explained are disingenuous. The salesperson did not understand the products sold and could not explain them. Local language PDSs struggle to find translations for English words like risk and loss but have no difficulty finding local words for profit or gain.

In court proceedings, lawyers with scant understanding of what they are arguing present cases before judges who understand less. Experts resemble ventriloquist dummies through which parochial arguments favoring their clients emerge. Neither the lawyers nor the judges understand the experts. Like a scene from the film The Reader, I spend an entire day in court reading my expert report of more than 200 pages into the court record, as it seems that no one has or can be bothered reading it.

Summary proceedings become epics. First-instance hearings go to a second and third. Omnibus hearings require trucks to transport the paperwork. Arbitration proves arbitrary. Alternative dispute resolution processes resolve nothing. There are appeals to higher powers, which prove indifferent and uninterested. Clients learn the reality of the words of Dennis Wholey, an American TV host: “Expecting the world to treat you fairly because you are a good person is a little like expecting a bull not to attack you because you are a vegetarian.”

By October 2010, the fees paid to lawyers, advisers, and managers involved in the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers reaches more than $1,000 million. Partners command $1,000 an hour; junior associates out of law schools are charged out at $500 an hour. One law firm charges $150,000 to compile bills and time records. Expenses include $263,000 for a few weeks’ photocopying, thousands for business class air travel, five-star hotels, and charges for limos waiting for meetings to finish. One bill includes a charge for $2.54 for gum at the airport. The fees include a payment of $1.5 million to a firm to monitor the fees paid.

Unsecured Lehman creditors expect less than 15 cents on the dollar for their claims, sometime in the future. A Basil Boothroyd poem about movies applies to finance: “Isn’t it funny / How they never make any money / When everyone in the racket / Cleans up such a packet.”

Nausea

The ambitious investments of Euro Swiss Bank (ESB) in AAA-rated MBSs, ABSs, and CDOs as well as private equity and hedge funds result in huge losses. In bridging the gap, the bank seems to be disappearing into it. At the annual shareholders’ meeting, hearing that Eduard Keller, ESB’s wunderkind CEO, will forgo his bonus, one elderly shareholder speaks of buying a larger handkerchief for his tears. Worried that Keller cannot dine at the Michelin-rated restaurant Stucki in Zurich, favored by bankers, a shareholder presents the CEO with a packet of sausages, a tin of Sauerkraut, and a tube of mustard. Keller resigns shortly afterward.

LSCF’s investors refuse to put in more money, forcing the fund to file for bankruptcy. Smitz asks me to continue advising on restructuring of several SIVs, CDOs, and hedge funds as JR fights for survival.

Mailer’s employer has survived, bloodied but unbowed. Over a drink, I outline my thesis on banking—back to the future, return to basics. Commercial banks take deposits, make loans. Investment banks provide advice and arrange equity and debt issues. Trading is curtailed. Finance becomes highly regulated, a smaller part of the economy. Mailer is unconvinced. “Dull. It’ll be dull.”

He rails about his bank’s “stupid” cost-cutting—crackdowns on first-class travel, five-star hotels, and gourmet restaurants. Employees fly economy, take buses, and trains. Taxis are permitted only during transport strikes. Limos are off the menu. Employee meals are $15 per person, matching the cost in the bank’s cafeteria. Client entertainment is limited to $150 for two. Mailer bemoans the “good old days” when salacious outings at an adult entertainment venue or brothel could be passed off as a restaurant where the name wasn’t obvious. The days of excess—bankers spending £44,000 just on wine during a meal at Gordon Ramsay’s Pétrus or spraying bars with vintage champagne, imitating Grand Prix drivers—are gone.

Mailer complains about banking salaries. “You can’t live in New York decently for less than a couple of million a year! And that’s just the basics.” The mortgage is $150,000 a year. The co-op maintenance and property taxes another $150,000, private school fees are $50,000 a child, the nanny is $60,000, and then there are private tutors. That’s before living expenses ($50,000). “They don’t have any idea of what a decent suits costs?” Mailer vents. There are cars, drivers, and summer vacations in the Hamptons or on Martha’s Vineyard.

Holly Peterson, daughter of Blackstone Group founder Pete Peterson and author of The Manny, an Upper East Side novel of manners, tells a reporter: “As hard as it is to believe, bankers who are living on the Upper East Side making $2 or $3 million a year have set up a life for themselves in which they are also at zero at the end of the year with credit cards and mortgage bills that are inescapable.” Candace Bushnell, the author of Sex and the City, observes that:

People inherently understand that if they are going to get ahead in whatever corporate culture they are involved in, they need to take on the appurtenances of what defines that culture. So if you are in a culture where spending a lot of money is a sign of success, it’s like the same thing that goes back to high school peer pressure. It’s about fitting in.1

In the Unites States, unemployment remains high with few new jobs being created. People downsize from houses to trailers, from trailers to streets. Wall Street wives shop for cheaper cuts of meat as the less fortunate go hungry. Speaking about the bankers, Ken Auletta, author of Greed and Glory on Wall Street: The Fall of the House of Lehman remarked: “Honestly, I was relieved that I’d never have to see many of them ever again. They were, with some exceptions, a greedy, selfish, deeply unpleasant bunch of people.”2

Crunch Porn, Crash Lit

Sales of Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead and Atlas Shrugged rise, coinciding with massive state intervention in the economy following market failures. One new group on the social networking site Facebook writes: “Read the news today? It’s like Atlas Shrugged is happening in real life.”

Alongside the Twilight series of vampire tales and Stieg Larsson’s Millennium trilogy, bookshops create crunch porn or crash lit sections. All authors saw the writing on the wall, predicted the crisis, and now offer solutions to the crisis to end all crises. Nouriel Roubini’s best-seller Crash Economics leaves no doubt that he predicted a crisis: “Roubini’s prescience was as singular as it was remarkable: no other economist in the world foresaw the recent crisis with nearly the same level of clarity and specificity.”3 But no one matches the prescience of Pope Benedict XVI. According to the Italian finance minister Giulio Tremonti, the Pope, then Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, in 1985 predicted that “an undisciplined economy would collapse by its own rules.”4

Books on economics by economists criticize other economists. As John Kenneth Galbraith pointed out, economics only provides employment for economists. It provides fruitful employment to authors explaining the theories (in good times) and debunking them (in bad times).

Journalists rush out blow-by-blow accounts of the collapse of Lehman Brothers and the subsequent financial market meltdown. Hastily written histories of firms and banking figures as well as personal perspectives and memoirs proliferate. Many find links between cocaine snorting, binge drinking, lap dancing, and the crisis.

Journalists go for the racy rippin’ yarn, achieving an immediacy of style that comes when the book was produced over a weekend or two. Economists aim for a desiccated drone (reminiscent of John Cage’s experimental work in the 1960s) to achieve the correct type of unreadability. Memoirs owe more to Gestalt sessions or accounting than Shakespeare. Some works read like nineteenth-century pamphlets, with equal measures of vitriol, self-righteousness, and broad prescriptions.

Reviewing Lecturing Birds on Flying, a polemic against the Black-Scholes-Merton option pricing model, The Economist questions a style exemplified by the final sentence: “Deliciously paradoxically, the Nobel could end up diminishing, not fortifying, the qualifications-blindness and self-enslavement to equations-led dictums that, fifth-columnist style, pave the path for our sacrifice at the altar of misplaced concreteness.”5 One reviewer on www.amazon.co.uk queries the book’s use of terms like “tumultuous tumultuousness,” “unconventional conventionalism,” and “dogmatic dogmatism.” He seeks clarification that a reference to an argument as “non-incoherent” means “coherent.”

Readers wander around like the Russian harlequin in Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, a cross between a star-struck cult member and a Shakespearean fool: “I tell you this man has enlarged my mind.”6

Economic Rock Stars

The financial media analyses every confused development in absurd detail. Crisis documentaries and films multiply at the same rate as losses.

Fêted as a rock star at Davos, the black swan thesis of Nassim Taleb attracts attention. The crisis may be a black swan (an unknown unknown), white swan (a known unknown) or gray (all of the above) swan. Taleb combatively attacks the charlatans—anyone who does not agree with him.

Economists and statisticians do not react well to being labeled pseudo-scientists of financial risk who disguised their incompetence behind maths. In August 2007, the imbeciles, knaves, and fools (Taleb’s descriptions) devoted an entire issue of The American Statistician to the black swan hypothesis. On the Charlie Rose Show, Taleb dismisses all criticism as ad hominen, a logical fallacy that the validity of a premise is linked to the advocating person. Statisticians do not like the grandiose prose or tangential literary flights that Taleb defends, arguing that his book is a work of literature and philosophy.

Taleb suggests that Myron Scholes, the co-author of the famed option pricing model, return his Nobel Prize as he is responsible for the crisis. He points to the failures of LTCM (where Scholes was a partner) and a subsequent hedge fund he started. Taleb suggests Scholes should be playing Sudoku in a retirement home, not lecturing anyone on risk. Stating he does not play Sudoku, Scholes accuses Taleb of being ‘popular’, trying to make money selling his book. It is unclear why Taleb wants to be taken seriously in the academic circles he despises.

Nouriel Roubini is everywhere—CNBC, Bloomberg TV, CBS, ABC, WSJ, NYT, NPR, HBO, FT, and Der Spiegel. If you want to know where the man is going to appear next, then you just check Roubini’s Tweet. His ubiquity suggests that there are several clones of the man. His exotic background, accented English, and the moody look of the Ancient Mariner who has seen catastrophe makes Roubini the iconic crisis brand. To monetize his celebrity status, Roubini rebrands his consulting service as roubini.com, rather than RGE Monitor. Detractors argue that Roubini predicted a different kind of crisis for a long time, switching in late 2006 to warnings about U.S. housing and a global recession, adroitly fitting his narrative to events.7

Financial people believe strongly in their superior intelligence. On July 22, 2001, in an open letter to the economist Joseph Stiglitz, Kenneth Rogoff wrote: “One of my favourite stories...is a lunch with you...you started discussing whether Paul Volcker merited your vote for a tenured appointment at Princeton. At one point, you turned to me and said, ‘Ken, you used to work for Volcker at the Fed. Tell me, is he really smart?’ I responded something to the effect of ‘Well, he was arguably the greatest Federal Reserve Chairman of the twentieth century.’ To which you replied, ‘But is he smart like us?’”

Reviewing Stiglitz’s book Globalisation and its Discontents, Rogoff wrote that:

I failed to detect a single instance where you, Joe Stiglitz, admit to having been even slightly wrong about a major real world problem. When the US economy booms in the 1990s, you take some credit. But when anything goes wrong, it is because lesser mortals like Federal Reserve Chairman Greenspan or then-Treasury Secretary Rubin did not listen to your advice.

Rogoff concluded that Stiglitz was “a towering genius...you have a ‘beautiful mind.’ As a policymaker, however, you were just a bit less impressive.”8

Writing in his preface to Benjamin Graham’s Intelligent Investor, Warren Buffet observed that: “not only does a sky-high IQ not guarantee success but it could also pose a danger...nobody would be allowed to work in the financial markets in any capacity with a [IQ] score of 115 or higher. Finance is too important to be left to smart people.”

Showtime

A 2006 book Traders, Guns & Money, pointing out the dangers and risks of derivatives, attracts occasional media interest. My naturally pessimistic view of the world proves useful, coinciding with the times. People are forgiving if things turn out better than predictions.

In 2009, an Asian stockbroking firm invites me to speak at investment conferences in Tokyo and Hong Kong. I am part of the chorus, support for the mega-stars. In Japan, celebrity anti-exuberance advocate9 Robert Shiller in the course of a short speech, manages to mention his forthcoming book at least a dozen times.

In Hong Kong, the world’s first and only celebrity economic historian10 Niall Ferguson gives a keynote address on Chimerica, the relationship between China and America. Well-known for his books and Channel 4 series, Ferguson was named by Time magazine in 2004 as one of the 100 most influential people in the world. Jealous colleagues acknowledge his brilliance but criticize his love of celebrity, adulation, and money. The Harvard heartthrob reportedly charges around $100,000 per speech, earning $5 million a year, comparable to a high-ranking banker.

The speech takes its inspiration from the film The Painted Veil, based on Somerset Maugham’s story of infidelity. China and America have a marriage, Ferguson argues, that is on the metaphorical rocks. A few months after the speech, the London Daily Mail carries a story of Ferguson’s own marital problems. The article chronicles a £30,000 40th-birthday party for his mistress, Somali-born former Dutch politician Ayaan Hirsi Ali, to which Ferguson also invited his wife.11

In Lewis Carroll’s tale, Alice confesses that: “One can’t believe impossible things.” The Queen disagrees: “Why, sometimes I’ve believed as many as six impossible things before breakfast.”12 In the Alice in Wonderland world of financial media, it is essential to say and believe six impossible things every minute. In a March 2009 interview with Today Show’s Jon Stewart, Jim Cramer admits that Mad Money was “an entertainment show about business.” Stewart eviscerates Cramer: “It’s not a f***ing game.”

Meta Money

At a Festival of Ideas, I meet a French semiotician, a branch of linguistics that studies signs and symbols. The global financial crisis is, he assures me, a test of post-modernism. Money and financial markets manifest a modern anxiety about the nature of reality. As in all modernism, the problem is the meta level. Modern finance creates instruments enabling the creation of new forms of money, abstracted from real things. Derivatives and securitization are meta-money, making traditional concepts of money otiose.

For him, the crisis is obvious. In post-modernity, the meta level eventually dominates the primary level it emanates from. The cotton-candy money of financial alchemy dominates ordinary money. This leads to circularity and self-reference—value becomes driven by itself, prices become a function of what you can borrow against the collateral, driving up value feeding on itself. Instruments designed to manage risk create new risks. Hedging of risks by individual participants creates risks for the system.

New instruments emerge, being traded in huge volumes among institutions essentially trading with themselves. They undertake transactions, and price them and book fictitious earnings, neglecting to establish whether any of it is real or makes economic sense. The function of money markets to raise and invest money is systematically undermined. The true function of money as a mechanism for exchange, a store of buying power, and a measure of value is corrupted.

He explains: “All this is absolutely obvious, of course, except to economists and bankers.” This may explain why Siegmund Warburg, the founder of the eponymous UK merchant bank, favored hiring graduates with a background in the classics, believing that all other knowledge was ephemeral.

In November 2009, the auction of Andy Warhol’s 1962 silk-screen painting 200 One Dollar Bills confirms the French semiotician’s view. The painting’s title is literal, as the work is simply an accurate rendition of 200 $1 bills. The catalogue describes the piece as Warhol’s response “to the post-war world’s media and consumerist saturation” via “a form of art that would remove the hand of the artist, creating the same sense of distance and disconnect that was emerging in the world around him.”13 At a time when real money was rapidly losing value, the price paid for the painting meant that each painted dollar bill depicted in the work was worth $219,000.

Economic Trivialities

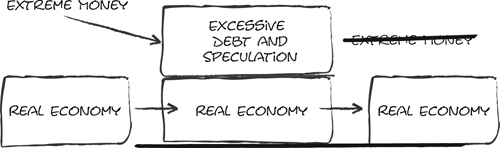

Asked to explain what has happened, I draw on the back of a napkin (Figure E.1). There is a box—the original real economy. In the age of capital, a larger economy appeared, really two boxes stacked on top of each other—the real economy and the extreme money economy, with its excessive debt and speculation. In the global financial crisis, the extreme money box disappeared, leaving only the smaller real economy once more.

Figure E.1. The extreme money economy

The world now has less wealth and more debt and may grow at a lower rate. Improvements in living standards, once accepted as routine, are likely to slow. For some countries or parts of society, which have lived beyond their means, living standards will need to fall, perhaps sharply.

In a world of increasing inequality, a small group will get even richer, parlaying scarce skills into a greater share of the economic pie. Many people will be marginalized, leading an increasingly precarious and uncertain existence in a netherworld of job insecurity and stagnant incomes. As journalist Peter Gosselin forecast: “comparatively few enjoy great wealth at almost no risk, while the majority must accept the possibility that any reversal—whether of their own or someone else’s making—can destroy a lifetime of endeavor.”14

In an economically fragile world, ordinary people everywhere view the future for themselves and their children with trepidation. Facing uncertain career prospects, even well-educated young people can feel hopeless and increasingly disenfranchised: “I have every possible certificate. I have everything except a death certificate.”15

Companies torture themselves financially to survive and maintain profitability. In the short run, businesses make money, squeezing costs, cutting back staff, and reducing benefits. They create jobs only in countries where labor is cheap and growth prospects are better. But eventually low economic growth will bite, eroding profits.

The heroic bet on growth and inflation to rescue the world from the problem of excessive debt levels may not succeed. Public borrowing cannot substitute fully or indefinitely for private demand and eventually governments will be forced to reduce debt. In 1939 Henry Morgenthau, secretary of the U.S. Treasury, admitted as much: “We have tried spending money. We are spending more than we have ever spent before and it does not work.”16

Anticipating increased scrutiny from investors in the aftermath of the continuing European debt crisis, governments everywhere try to improve the state of public finances. They cut back welfare payments. Increases in the retirement age force most workers to work literally until the grave, as their private retirement savings are generally inadequate. Governments put up taxes, creating employment for a vast industry of accountants, lawyers, and private bankers, who will ensure that those who can afford to pay their fees will not pay any more than the bare minimum of tax.

World leaders flit between summits, performing John Holbo’s “two step of terrific triviality” for the media: “say something that is ambiguous between something so strong it is absurd and so weak that it would be absurd even to mention it. When attacked, hop from foot to foot as necessary, keeping a serious expression on your face.”17 The level of the policy debate barely rises above the level of undergraduate economics. Despite mathematical pretensions, the discussion is “conducted in terms that would be quite familiar to economists in the 1920s and 1930s” highlighting “the lack of advance in our knowledge in 80 years.”18

There is no simple, painless solution. The world has to reduce debt, shrink the financial part of the economy, and change the destructive incentive structures in finance. Individuals in developed countries have to save more and spend less. Companies have to go back to real engineering. Governments have to balance their books better. Banking must become a mechanism for matching savers and borrowers, financing real things. Banks cannot be larger than nations, countries in themselves. Countries cannot rely on debt and speculation for prosperity. The world must live within its means.

Reforming the economy, reining in extreme money, is not difficult but comes with short-term painful costs and longer-term slower growth and lower living standards. Unpopular and politically untenable trade-offs mean that policymakers take a path of least resistance, committing more money to restoring the status quo ante using public debt to prop up the system, absorbing private losses and slowing the reduction in debt. German finance minister Peer Steinbruck questioned the approach: “When I ask about the origins of the crisis, economists I respect tell me it is the credit financed growth of recent years and decades. Isn’t this the same mistake everyone is suddenly making again?”19

The world desperately wills itself to believe that the crisis is over, the good times are returning. Gatsby, too, built himself an illusion to live by. Briefly his dream seemed so close that it was almost within reach. But “he did not know that it was already behind him.”20

This Time, It Is No Different!

Failure is generally not fatal but failure to change can be. But no real progress is possible until everybody faces up to the fundamental problems. Yet no one seems to have learned anything at all.

At the 2011 World Economic Forum at Davos, a Report—More Credit with Fewer Crises: Responsibly Meeting the World’s Growing Demand for Credit—forecasts that global borrowings will double between 2009 and 2020 to $213 trillion, a growth rate of 6.3 percent per annum. This follows a doubling of global credit between 2000 and 2009 from $57 trillion to $109 trillion, a 7.5 percent compound annual growth rate. There is little acknowledgment of the need to curtail the growth of debt or the problems of debt-fueled economic growth.

Policy makers and academics continue to mistake the beauty of their models for reality. New bank regulations rely on discredited models and ratings for assessing creditworthiness. Regulators argue that there is nothing better or that the new models are improved.

The intellectual commitment to defend the old ways is formidable. In a 2010 paper, economists Olivier Coibion and Yuri Gorodnichenko provide an elegant and inventive reinterpretation of recent history, arguing that the Great Moderation was the product of “good public policy.” The crisis that had thrown millions out of work, created untold hardship, and required massive government support to avoid a total collapse of the global financial system is dismissed as a “transitory volatility blip of 2009.”21 Economist Richard Posner identified the barriers to progress: “Professors have tenure...They have techniques that they know and are comfortable with. It takes a great deal to drive them out of their accustomed way of doing business.”22

At the 2011 Davos Forum, the world’s major banks tell politicians to stop bashing bankers, as it is a barrier to economic growth. Earlier, Robert Diamond, CEO of Barclays Bank, told a UK parliamentary committee investigating bankers’ bonuses that: “the period of remorse and apology...needs to be over.”23 Banks and financiers argue that what is good for them is good for everybody. The lobbying power of financial institutions means that real change will not or cannot be made: “The banks are still the most powerful lobby on Capital Hill: they frankly own the place.”24

Remuneration in the financial sector returns to pre-crisis levels. In 2010, hedge fund manager John Paulson earned $5 billion, higher than the $4 billion payday from his successful 2007 bets against subprime mortgages. The amount was almost equal to the $6.4 billion total net worth of Steven Cohen, the head of hedge fund SAC Capital. Appaloosa Management’s David Tepper made $2 billion; Bridgewater Associates’ Ray Dalio made $3 billion. Steve Cohen was rumored to have earned $1 billion in 2010.

The huge payments do not always reflect exceptional returns. Appaloosa and Bridgewater earned high returns of around 30 percent from successful bets, anticipating the government’s actions, flooding the world with money. But the average hedge fund gained a little more than 10 percent in 2010, below the 15 percent gain of the Standard & Poor’s 500 stock index and 19 percent return of average stock mutual funds. Paulson’s $36 billion Advantage Plus fund earned 17 percent, whereas another fund returned 11 percent. Despite this, Paulson earned a 20 percent performance fee.

Bankers’ earnings also recover, largely underwritten by government support of the financial system. Apologists argue that bankers are doing vital work to support the economy, justifying their pay as merely sharing in the profits that they generate. They complain that they are poor cousins to the hedge fund managers. The 36,000 employees at Goldman Sachs, the most lucrative of investment banks, took home just more than $8 billion in 2010, less than twice John Paulson’s earnings. Goldman Sach’s CEO Lloyd Blankfein, who earns a few tens of millions, must feel like a mere pretender at gatherings of the business elite.

Hedge fund managers receive all earnings in cash. Some of the profits are classified as long-term capital gains, taxed at lower rates than normal income tax rates. Bankers complain that they receive only part of their bonuses in cash now. Regulators want them to receive most of their bonuses in shares or other instruments, which are deferred in time and linked to the performance of their institutions. The protests are disingenuous. Derivative traders devised strategies long ago to hedge shares received by bankers and executives as part of compensation packages, breaking the link between compensation and the firm’s ongoing performance, dooming regulators’ efforts.

The problem is that a large part of the profits are not actually cash, but unrealized paper gains based on sometimes dubious market values for illiquid instruments and even more dubious models. The deadly pathology of finance—the gaming of bonus systems, manipulation of valuations, and accounting tricks—continues. As one observer notes: “It is simply amazing to me how much money you can make by shuffling papers. We have come a long way from our industrial giants.”25

In New York, credit-crunch tours take in the original Lehman Brothers building and New York’s Federal Reserve. In Bowling Green Park, downtown Manhattan, visitors still pose to have their photos taken near Arturo di Modica’s statue of a charging bull. Guides show tourists a real toxic asset—a thick prospectus for a 2006 $1.5-billion subprime CDO that was rated AAA where investors lost almost all their investment. The guide explains that the $185 billion of the taxpayer bailout would fill an entire alley near the AIG building to a height of nearly 7 feet (2 metres).

In their offices, financiers are little changed. Traders bet the house’s money in the same old “double up.” You bet $100 on a coin toss—tails! If you win then you have a $100 profit. But if you lose, you simply bet double the amount—$200—on tails the next coin toss. If the coin comes up tails, then you win $100—the $200 you bet less the $100 loss on the first toss. If the coin comes up heads, you simply double up again, betting $400. The assumption is that the coin must come down tails eventually, allowing you to win your $100 back. The only problem is that you could run out of money and be bankrupt before the coin comes up tails. You are risking higher and higher losses betting that the coin must come up tails at some stage.26 But traders don’t play the game with their own money, they play with other people’s money.

Trading culture remains largely untouched. A drinking game, icing, sweeps banks. You surprise a bro with a bottle of Smirnoff Ice any time, any place. If caught, the bro gets down on one knee, chugs the bottle. If he happens to whip out his own bottle, the icer gets owned, having to drink both. Andy Serwer, managing editor of Fortune, captured the period:

The party is over until it comes back again...I’ve been around long enough to see that we have these cycles. These guys get their cigars and champagne. They have a great time. The whole thing blows up. But then they re-emerge years later. This one is a really bad one. But I don’t think Wall Street is dead.27

As Scottish philosopher David Hume knew: “All plans of government, which suppose great reformation in the manners of mankind, are plainly imaginary.”

Suicide Is Painless

Financial problems, environmental issues, management of finite energy, food and water resources, and lower wealth increasingly converge in a toxic brew. The choices are pure Woody Allen: “More than any other time in history, mankind faces a crossroads. One path leads to despair and utter hopelessness. The other, to total extinction. Let us pray we have the wisdom to choose correctly.”

Ordinary people everywhere bear the cost. I think back to the people at the Money Show, wondering how Mary and Greg and the others are doing in their efforts to secure prosperity.

After the Investment Conference in Hong Kong, I leave the hotel and make my way to the airport train, through the Central Business District. Tens of thousands of Filipino women, who work as maids to monied business people, crowd every inch of the public space and sidewalks outside stylish skyscrapers, luxury hotels, and fashionable shops. Hotels and shopping arcade guards keep the women from using their restrooms.

On their only day off, the women meet to picnic on pieces of cardboard, read books, and write letters to the families they left behind. Poorly paid, often abused, they work long hours to support extended families back in the Philippines. In the hustle and bustle of Hong Kong’s financial center, they are the only people who smile and laugh. Among them, there is a rare sense of community.

Talking about the human effects of the crisis, a friend tells me a story about Indonesia during the Asian financial crisis more than a decade ago. Fluent in Bahasa Indonesia, he overheard a conversation one night outside the hotel where he was staying. A mother and her two daughters were discussing who would sell herself that night to feed the family.

The crisis has led to cutbacks in the number of Filipino maids in Hong Kong. They face competition from women from mainland China. On the street, an older woman comforts her younger companion. She lightly touches the other woman’s head in a sympathetic gesture, recalling playwright Harold Pinter’s last words in No Man’s Land: “Tender the dead as you would yourself be tendered, now, in what you would describe as your life.”

Arriving early for a meeting in London’s Canary Wharf, I notice a small street stand erected near the Underground station by the English Teachers Union to recruit teachers. Two affable women explain that they heard that there is “a bit of financial crisis.” Well-educated and highly motivated bankers who were losing their jobs might consider a new career teaching. Questioned about the 90 percent reduction in salary, one recruiter responds: “If you haven’t got a job then it’s not relevant is it? It was never real money and it wasn’t going to ever last was it?”

One turns to attend to her small baby. The child’s eyes catch mine for a brief moment. I think about the future of all children, everywhere. I think of the words of Viktor Chernomyrdin, the malapropism-inclined former Russian prime minister, describing government policies designed to ensure: “We are going to live so that our children and grandchildren will envy us!”28

Former soccer star Eric Cantona calls for a new French revolution, urging citizens to withdraw money from banks. Le Monde jokes that Cantona would need a van to withdraw his savings, which he has built up through celebrity endorsements. Baudouin Prot, CEO of France’s largest bank BNP Paribas, considers: “This recommendation to withdraw deposits is criminal.” French Finance Minister Christine Lagarde considers Cantona “a great footballer” but recommends against following his financial reform proposals.29 Cantona does not carry out the threat. Ordinary people everywhere lack “the power to translate their hatred into active opposition...cherishing it within their bosoms, warming themselves with its rancorous fire.”30

The Turning World

Poet Lord Tennyson wrote in Locksley Hall: “Forward, forward let us range, / Let the great world spin for ever down the ringing grooves of change.” Past my use-by-date, I wind up my business affairs.

On a trip to London finishing off some business, I travel to the De La Warr Pavilion at Bexhill-on-Sea to view an exhibition of the d’Offay collection of Joseph Beuys’s work. In an upstairs room in the gallery, there is a sculpture, Scala Napoletana, a piece the artist finished a few months before his death. The work consists of an old ladder, which Beuys found on the Island of Capri. It is suspended from two lead spheres by wire. Worn, fragile, its paint peeling, the ladder hangs in the middle of the display space, elegiac and solemnly eloquent. Beuys was deeply influenced by shaman beliefs of ascending the upper regions of existence. Steeped in the artist’s awareness of his own death, the ladder seems to symbolize the final ascent that we all make, conveying its danger, desperate hope, uncertainty, and inevitability.

In the train back to London, I turn my attention to a book by German philosopher Walter Benjamin. His unfinished Arcades Project was to have been a study of capitalist modernity, based on Paris’s neglected covered passages, symbolic of a golden age of production, consumption, and consumer society. For Benjamin, the alcoves were the repository of discredited dreams. The ninth thesis from the essay “Theses on the philosophy of history” catches my attention:

A Klee painting named “Angelus Novus” shows an angel looking as though he is about to move away from something he is fixedly contemplating. His eyes are staring, his mouth is open, his wings are spread. This is how one pictures the angel of history. His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe [that] keeps piling wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing in from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such a violence that the angel can no longer close them. The storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.31

Was the global financial crisis bringing to a close a grand arc of human history? Over the last 40 years, financial fundamentalism and financial oligarchs changed the world. Extreme money, the idea of universal wealth and prosperity engineered by financial alchemy, was immensely powerful, impossible to resist. Was it possible to turn back? As Dom Cobb (played by Leonardo DiCaprio) understands in the film Inception, the hardest virus to kill is an idea.