Chapter 8. The Carry Trade

“What we may be witnessing is not just the end of the Cold War or the passing of a particular period of post-war history, but the end of history as such: that is, the end point of mankind’s ideological evolution and the universalization of western liberal democracy as the final form of human government.”

Francis Fukuyama, 1990

The “carry trade” creates cheap money by borrowing in a currency with low interest rates, putting money into currencies with high interest rates, and pocketing the difference. Japan’s market crash in 1990 brought low rates in its wake and created a great carry trade—and in 2009, investors borrowed U.S. dollars in another carry trade after the crash in the United States. The cheap money inflates bubbles. Once investors use it to fund investments in stocks, those markets rise and fall in line with the yen’s exchange rate.

Japan loves to celebrate the New Year with performances of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. On the night the 1980s ended, the Ode to Joy seemed appropriate. The world had just watched the Berlin Wall fall and communism subside across the Eastern European Bloc, soon to provide capitalism with a swathe of new emerging markets. Months earlier in China, student demonstrations ended in a massacre in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square. That crisis forced the country’s supreme leader Deng Xiaoping to offer his people a new deal: The government would guarantee them economic growth in exchange for continued lack of democracy. That growth would come through capitalism red in tooth and claw and in 1990 China reopened the Shanghai Stock Exchange, which had been shuttered since it was closed by communist rebels in 1947.

These events changed the face of capitalism. But Japan administered an even greater shock. At the time the world’s biggest stock market, it was caught in a bubble that peaked on New Year’s Eve 1989. The international effects of the loss of wealth that resulted could easily have been as severe as the banking crises and depressions that followed Wall Street’s Great Crash of 1929. But instead, as Japan fought the crisis, it turned its currency into a source of cheap funds for the rest of the world. What is now known as the “yen carry trade” would in time help bubbles to form in assets across the globe.

It is hard to exaggerate either the insanity of the bubble in Japan or the severity of what followed. In 1989, it briefly accounted for more than half of the world’s entire stock market valuation,1 even though its economy, about one-third of the size of the United States, accounted for only 8 percent of the world’s gross domestic product. This was insane. Land and real estate prices were even more blatantly overvalued. At one point, the land on which the imperial palace is built in Tokyo was worth more than all the land in California.2 Financial liberalization in the 1980s, making it easier to raise mortgages, and encouraging foreign investment, fed the bubble.

From 1985 to 1989, the Nikkei 225, Japan’s main stock index, quadrupled—and over the next five years it lost more than 80 percent. It has never staged a lasting recovery. At the end of 2009 it was oscillating around the level of 10,000 that it first reached in 1985. At its peak it was nearly 40,000.

The bubble had burst under its own weight. Houses grew so expensive as to threaten social unrest, and when the government tried to rein in mortgage-lending, borrowers defaulted, land prices dropped, and stock prices fell with them. In essence, it was a repeat of the Mexican crisis—intense capital flows and excessive lending led to a bubble and over-extended banks. The critical difference was that Japan was much bigger than Mexico.

As in Mexico, banks were points of weakness. Many mortgages extended at the mania’s height would never be repaid. If Japan’s banks admitted that and marked down their assets accordingly, then substantially the entire banking system would be bankrupt. So regulators did not force the issue and the banks limped on, unable to stimulate the economy, while Japan lapsed into outright deflation—falling price levels—as the money dried up.

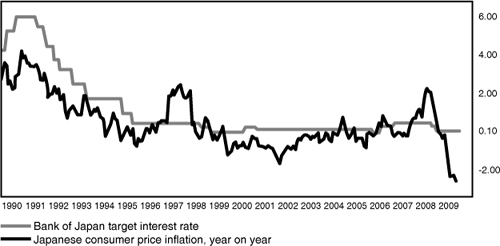

The key for international investors lay in the government’s response, which was to cut rates in an attempt to get money flowing once more. On New Year’s Eve 1989, the Bank of Japan’s target lending rate stood at 4.25 percent. Then came a long and steady dive as activity stagnated and repeated doses of cheap money failed to stimulate the economy or the banks back into life. By 1995, the discount rate fell to 0.5 percent. In 2001, it reached 0.1 percent and stayed there. Figure 8.1 shows how activity dried up.

Figure 8.1. After the crash: cheap money and deflation

This did not happen in a vacuum. Such low interest rates weakened the yen and made it maddeningly difficult for Japanese people to save money. That created an opportunity for international traders with access to the foreign exchange market, which came to be known as the “yen carry trade.” This is perhaps the most controversial and least visible aspect of the global bubble. “Carry” is traders’ jargon for the cost of holding a security. For example, holding a gold bar costs money, because the storage is very expensive. But borrowing in yen is almost costless—from the late 1990s, that cost was only the minimal interest rate charged on Japanese accounts.

Higher interest rates tend to strengthen a currency. If the UK raises rates while the United States does not, for example, that should attract funds out of dollars into pounds, because the pound has become a more attractive place to park money. That flow of money will strengthen the pound. Hence low rates tend to lead to persistently weak currencies. And that opens up the possibility of a great “carry trade”—borrow in yen, put the money into a currency with higher rates, and pocket the difference, or “carry.” Providing the yen does not suddenly rise, making it more expensive to repay the loan, this is very easy money that can be put toward opportunities elsewhere.

Markets’ self-fulfilling nature takes a role. The more investors attempt to operate a carry trade, the safer a bet it will be because the flows of money out of Japan that they create will weaken the yen. But if volatility rises, or investors get nervous, they will take their profits from the carry trade and strengthen the yen in the process. While this trade worked beautifully for most of the time, it was an intrinsically dangerous way to raise money, with the risk that a spike in volatility could send all traders’ calculations awry. This meant that for the years of Japan’s malaise, its currency moved on the animal spirits of traders around the world, rather than on any factors endemic to the Japanese economy.

Who exactly practiced this carry trade remains a subject of passionate debate. It eludes precise measurement. “Mrs. Watanabe”—the popular tag for the typical Japanese retail investor—is a plausible candidate. She could make no money on domestic bank accounts, or in the local stock market, but could profit from the artificially cheapening currency by investing elsewhere. The more Japanese investors entrusted their savings overseas, the more the yen weakened. This weakening itself made Mrs. Watanabe richer and encouraged her friends to do the same thing. A new category of savings products arose as “Uridashi” bonds offered Japanese investors returns denominated in New Zealand or Australian dollars, or South African rands—all currencies with far higher interest rates.

But it was not just Mrs. Watanabe. International traders also made money by carry trading. That can be seen by the way the yen would spike within minutes in response to a shift in the global appetite for risk—a speed beyond Mrs. Watanabe’s reach. And Mrs. Watanabe had nothing to do with the extension of the carry trade to other currencies such as the U.S. dollar and Swiss franc in the next decade, which was prompted by falling interest rates in other big economies.

After the Federal Reserve cut rates as low as 1 percent in the aftermath of the 9/11 terrorist attacks of 2001, the Bank of International Settlements (BIS) found that many traders started borrowing in dollars as part of carry trades.3 The Swiss franc, another currency with low rates, had the same phenomenon. Hungarians, freed from communism, often chose to take out mortgages denominated in Swiss francs. This gave them a low interest rate and freed them to invest elsewhere, but also exposed them to potential disaster if their own currency, the forint, should fall. In the 18 months leading up to January 2007, Hungarians borrowed about 3.25 billion Swiss francs ($2.6 billion at the time) for home mortgages, while the total stock of Swiss franc loans in Hungary reached about 7.5 percent of Hungary’s GDP at the time.4 Destination currencies for carry traders enjoyed phenomenal growth. According to the BIS, turnover in the Australian dollar rose by 150 percent between 2001 and 2004—a period in which Australian rates rose as U.S. dollar rates fell, and the Australian dollar gained strongly. This was driven by online technology, which made it easier to trade in these markets by increasing use of the carry trade.

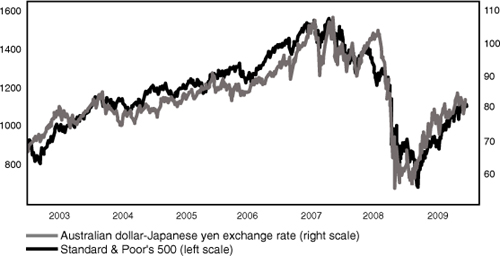

Japan’s implosion thus redirected big money flows. They found a home in freshly emerging countries, inflated bubbles there, and also helped to inflate a synchronized super-bubble by providing a cheap but unstable source of funds for the whole world. As the practice took hold, it distorted the world economy and the terms of global trade by making some currencies undervalued and others overvalued. As Figure 8.2 shows, in the period from 2003 to 2009, the carry trade exchange rate of the Australian dollar against the yen was almost perfectly correlated with the U.S. S&P 500 stock index—a bizarre outcome that showed both markets were inefficiently priced.

Figure 8.2. Perverse correlations: U.S. stocks and the carry trade

History had not ended in 1990. But the yen carry trade was not the only example of how investors could make money out of foreign exchange in a post-gold standard world. As the 1990s progressed, foreign exchange became an asset class in its own right.

In Summary

• The bursting of Japan’s bubble did not create crises elsewhere thanks to the emergence of new markets and to the carry trade, which effectively allowed global investors to enjoy low Japanese rates.

• The carry trade created extra funds for speculation and led to tight correlations between the value of the yen and then the dollar and stock markets. It is a bet on low volatility.