Chapter 17. Ending the Great Moderation

“Stability—even of an expansion—is destabilizing in that more adventuresome financing of investment pays off to the leaders and others follow. Thus an expansion will, at an accelerating rate, feed into the boom.”

Hyman P. Minsky, writing in 1975

Bubbles require low volatility and low interest rates, which make financial engineering possible. When volatility rose with the February 2007 “Shanghai Surprise,” followed by a rise in long-term interest rates, the super-bubble was ready to burst.

February 27, 2007 dawned, like all other days, in the East. It was a slow news day in Asia, but for some reason Shanghai traders started selling. Even after the mandatory midday break in trading, they kept selling. By the close, the Shanghai Composite, index for the biggest stock market in China—where many of the world’s hopes now resided—was down 9 percent for its worst day in a decade.

Traders in London and Frankfurt seemed mesmerized. European stock market fell, wiping out their gains for the year. Falls at the opening in Wall Street were a fait accompli after such awful overnight news. But the worst of the day was yet to come. Sell orders built up and became ever harder to process in the afternoon thanks to the market’s official “circuit-breaker” mechanisms that blocked traders from making big sales of stock unless share prices were ticking up. These rules had been in place since the 1997 Hong Kong crash forced New York’s stock exchange to close early, but they did not help. Instead, big “sell” orders banked up until suddenly the exchange’s computers caught up.

At 2:57 that afternoon, the Dow Jones Industrial Average stood at 12,346.33—down about 2 percent for the day. By 3:02, as computers finally caught up, it had dropped to 12,089.02—off more than 540 points for the worst day since the 9/11 terrorist attacks some five years earlier. Those few minutes shook the confidence of traders around the world. This day, destined to be known as the “Shanghai Surprise,” ended the years of the “Great Moderation.”1

The “Great Moderation,” a phrase used by economists, refers to the way the world economy grew with low volatility after the Federal Reserve under Paul Volcker tamed inflation in the early 1980s. Recessions were shorter and shallower. But during the Great Moderation in the economy, markets were as volatile as ever—which is not surprising, as markets’ daily movements reflect mass psychology more than the economy. Then, as the credit boom took hold, they enjoyed a moderation of their own.

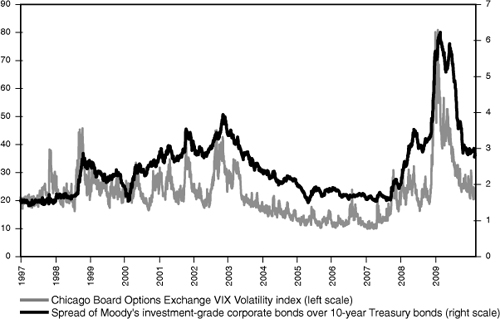

Volatility or fear can be measured using options prices. The Chicago Board Options Exchange’s Vix Index tracks the cost of insuring against future volatility in the stock market. The more investors are prepared to spend on options to protect against future volatility, the higher the Vix, which is nicknamed the “fear gauge.” The Vix peaked above 45 during the LTCM crisis. Normally, volatility itself is volatile, with brief spasms punctuating longer periods when markets are stable.

This was not the story of the middle years of the first decade of the twenty-first century. As Figure 17.1 shows, volatility dropped to historic lows and stayed there, due to artificially cheap credit. While credit is too cheap, markets can stay calm and in early 2007, the Vix dipped below 10 for the first time ever. On the Shanghai Surprise day, it rose by almost 60 percent to reach 18 and never retreated, ending the Great Moderation in the markets.

Figure 17.1. The markets’ Great Moderation—and the great meltdown that followed

Viewed in this context, we can see that the Surprise was less unusual than the moderation that preceded it. Arguably the reaction that day, and the violent volatility that followed, were even caused by the markets’ Great Moderation. This is exactly what Hyman Minsky, a maverick and largely overlooked left-wing economist, would have argued. The Surprise came just as many were looking at his work anew. Minsky argued that periods of moderation allowed some lenders to offer excessive credit, which forced other players to offer credit too cheaply until the cumulative excesses caused a speculative collapse. Without healthy regular doses of fear, he thought markets and banks would do something stupid. Low volatility made it easier and safer to take on debt, which would in turn smooth out volatility. As the perceived risk of corporate default fell, as shown in Figure 17.1, by the extra yield on corporate bonds compared to government bonds, so stock market volatility fell in almost perfect alignment.

The artificial stability of mid-decade, he would have suggested, unleashed a desperate race to extend credit on more generous terms. As he put it: “As a boom develops, households, firms, and financial institutions are forced to undertake ever more adventuresome position-making activity. When the limit of their ability to borrow from one to repay another is reached, the option is to either sell out some position or to bring to a halt, or slow down, asset acquisition.”2

This describes what transpired in 2007. The causes of the Shanghai Surprise are unimportant compared to the fact that it happened. Volatility for its own sake wrought a huge change in what financial engineers could do. It turned the carry trade into a risky proposition, and so as risk increased, investors rushed to buy the yen. Hence the yen and the U.S. stock market, after decades of being unrelated, suddenly became tightly correlated on the day of the Surprise. Both were responding minute by minute to changes in the market’s appetite for risk.

Volatility made transactions based on short-term credit—by this point a huge chunk of the market—inherently more risky. So much borrowed money lay behind the positions that had been built up that markets could turn violently as soon as it fled. Traders looked at the assumptions undergirding the markets’ Great Moderation, asked if they believed them, and decided that they didn’t.

This, rather than anything that happened in Shanghai, explains what happened. The incident was not about contagion from China. Instead, a different dynamic was at work: correlation. “The global macro backdrop to all of this is that almost every asset is more highly correlated to every other,” one trader confided to the Financial Times that day. “Chinese consumers and Joe Public in Detroit are no longer as dissimilar as they used to be.”3

The risks emanating from the United States were clear and menacing. More than 20 subprime lenders had filed for bankruptcy, and the ABX Index, measuring the cost of insuring against default, made the fear transparent for all. In January, it implied that there would be no defaults on that year’s mortgages. By the Shanghai Surprise two months later, it was predicting a default rate of almost 40 percent. That had alarming implications for U.S. consumers and hence the Chinese exporters who sell to them.

Therefore, many different investors in different markets made the same judgment on the same day to get out of the market. China happened to come first. Markets were so interconnected that it took traders in Shanghai to alert U.S. traders to problems in the American credit market

In the weeks after this shock, markets recovered, although volatility remained higher. There was even a final splurge of mortgage issuance. Thanks to herd psychology, many bankers made the same calculation: While others were taking risks, and profiting, there was nothing to do but join them. Bankers, like mutual fund managers, were judged against their peers. Chuck Prince, then the CEO of Citigroup, explained this with an unforgettable metaphor that became his epitaph when he was forced to resign months later. “When the music stops, in terms of liquidity, things will be complicated,” he confided to the Financial Times. “But as long as the music is playing, you’ve got to get up and dance. We’re still dancing.”4

It took the bond market to bring that dance to an end and also end the economic Great Moderation itself. Bond traders rely heavily on the patterns they can discern in trading charts. And long-dated treasury bonds, the “risk-free” securities that provide a baseline for pricing assets throughout the financial world, were in the grips of a strong and reliable long-term trend.

Bond yields follow a cycle, rising when central banks are tightening interest rates. But since Volcker had tamed inflation, each successive peak had been lower than the one that preceded it. A perfectly straight downward-sloping line joined the peaks. Inflation will eat away at the value of payments made by long-dated bonds, meaning that rising expectations for inflation will push down bond prices, while pushing up yields. Thus this downward trend showed faith that inflation was steadily being squeezed out of the system—a symptom of the economic Great Moderation.

But after the Shanghai Surprise, bond yields rose menacingly. So much easy credit would only be expected to fan the flames of inflation. Traders asked whether the longstanding assumption of permanently falling inflation could stand. They decided it could not.

On June 7, 10-year yields reached 5.05 percent. As Figure 17.2 shows, this apparently unremarkable event breached the downward trend line for the first time in 22 years. Traders all around the world instantly recognized the significance and panic ensued. Everyone wanted to dump bonds. Yields shot up. And with this, the second vital support for the imaginative financial engineering of the markets’ Great Moderation had been kicked away.

Figure 17.2. A breach in the trend: bond yields spiked up in the summer of 2007

This had a direct effect on credit investments, which are priced with respect to treasury bond yields—the higher the risk, the higher the extra “spread” compared to treasuries the borrower will have to pay. When bond yields rose, traders had no choice. They could not reduce still further their estimate of the extra risk their investments carried compared to Treasuries. Fresh subprime bankruptcies made that impossible.

So they had to accept that the extra spreads they were paying were far too low and would need to increase to reflect the true risk. That meant raising the interest rates paid out on higher risk bonds to a point where they were no longer affordable for borrowers, along with cutting the price of debt for anyone wanting to sell it in the secondary market. The scene was set for the prices of structured credit investments to go into free-fall.

In Summary

• The financial engineering behind the bubble relied on low volatility and low rates. Hyman Minsky showed these can drive higher volatility. Once they had been removed, the structures could not stand.

• It was the treasury bond market that called time on the bubble—and it may well play that role again in the future.