Chapter 21. Bastille Day: Reflexive Markets

“First, market prices always distort the underlying reality which they are supposed to reflect. The degree of distortion may range from the negligible to the significant. Second, instead of playing a purely passive role in reflecting an underlying reality, financial markets also have an active role: They can affect the so-called fundamentals they are supposed to reflect.”

George Soros1, explaining the two principles of his theory of markets

Synchronized markets warp perception and force politicians and investors alike into historic errors—but eventually collapse under their own contradictions. In 2008, investors bet simultaneously on a banking collapse and an oil spike and caused an inflation scare in the middle of a credit crisis. When it ended, oil, foreign exchange, and stock markets all reversed, setting the scene for collapse.

July 14, Bastille Day, is a day of revolution, and in 2008, it was the moment when the old regime for markets fell. Entering Bastille Day, there had been one way to make money in 2008, which was to bet against Uncle Sam, and particularly against the Fed. The logic: The U.S. financial system was critically wounded and the Federal Reserve had given up any attempt to stave off inflation or to avoid moral hazard. Instead, it would go all out to rescue U.S. banks by cutting rates and doing anything else necessary. The market response to this was so extreme that it forced central banks to fight inflation by raising rates—and thus killed off the rally.

This was a classic example of a “negative feedback loop,” or what the investor George Soros calls “reflexivity.” By this, Soros means that our perceptions of the world, as expressed through buying and selling, can change the world itself. Once markets become reflexive, they reflect flawed perceptions rather than a prior “reality”—but the market’s version of “reality” is no less real because of that. The reflexive events of the summer of 2008 are the textbook case of how synchronized markets have evolved so that they can force policy mistakes and damage the economy.

The chain of events went as follows. After the Bear Stearns rescue and the rate cut that followed it, traders reasoned that the Fed had given up on its currency. So they bet the dollar would decline. A great way to do this, as the experience of the 1970s had shown, was to buy oil, which would retain its value as the dollar dropped. They could also directly sell the dollar in favor of other currencies on the foreign exchange market. Belief in big ideas like “decoupling” and the BRICs made the idea seem all the better.

If hedge funds really wanted to profit, however, they could be more aggressive by selling short the shares of U.S. banks and buying oil. This was a connected bet that the U.S. banks would keep sinking and that the cheap money to save them would weaken the dollar and send money pouring out of the United States. Just like the rally for Internet stocks after the rescue of LTCM, or the rush for the BRICs in 2007, they were betting that cheap money to cure an ailing patient would instead over-stimulate parts of the world economy that were already in robust health.

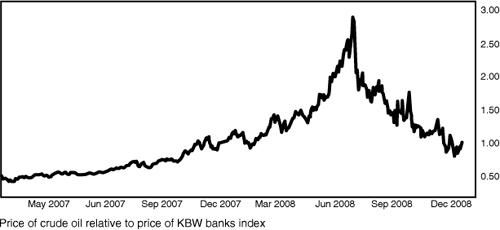

Returns on this trade were spectacular and are illustrated in Figure 21.1, which shows the returns made by selling short U.S. bank shares and using the money to buy crude oil futures. By July 14, this trade had made a profit of 168 percent for the year. The trend for the rest of the world was only a little more muted. Shorting the broader MSCI World financials index, which includes banks from around the developed world (most of which were exposed to U.S. housing), instead of U.S. banks would have netted 114 percent.

Figure 21.1. Betting against Uncle Sam: buy oil, sell banks

By July, the oil price reached $145 per barrel, having doubled since the previous August, and tripled since the previous January—astonishingly, this happened against a background of declining global demand for oil and rising supply.

The longer term problem with the trade was that it was internally illogical. If the United States was really to fall into the grips of an acute banking crisis, then its economic activity would slow and it would buy less oil. It was the world’s biggest oil consumer, so this meant oil would fall, not rise. But the flows of money pushing up oil, in several distinct markets, were so heavy that the price could be taken to an extreme.

This “Sell Uncle Sam” trade put central banks under intolerable pressure. Oil is a big chunk of the consumer baskets on which inflation indexes are based, so rising oil led directly to higher inflation (just as it had done in the 1970s). Now that markets appeared no longer to trust central banks to keep inflation under control, the United States was back on the “oil standard” that had governed its economy in the 1970s. This was reflexivity—by betting on a return to inflation, traders had in a very real way helped inflation come to pass.

A credit crisis would normally lead to deflation. But as oil shot upward, central bankers took their eyes off the credit market and felt forced to declare war on inflation. Indeed, some central bankers virtually declared war on each other.

Central bankers try never to talk about their currency if they can avoid it. But on June 3, speaking by satellite to a conference in Barcelona, Ben Bernanke did just that. He complained of an “unwelcome rise in import prices and consumer price inflation” and said he was “attentive” to the implications that the weak dollar could have for inflation and inflation expectations. When the dollar weakens, import prices rise, and this forces up inflation, so this was an obvious attempt to push the currency higher by talking up its prospects.

Two days later, Jean-Claude Trichet of the European Central Bank (ECB) went one better, virtually promising to raise rates. He announced that he had “markedly higher” new projections for European inflation, that there was a risk of high oil prices leading to a “wage/price spiral” and that “we are in a state of heightened alertness.” He also predicted that economic growth would soon hit bottom at 1.5 percent annually and then recover.

A rate rise fought inflation, but it also strengthened the euro even more against the dollar because it raised the rates paid by eurodenominated deposits. So the dollar fell amid chaotic conditions in which many traders took severe losses. If central bankers were worried by inflation, the logic went, it must make sense to buy oil. With markets now helplessly interconnected, oil rose still more, while the sell-off of banks continued apace. Bizarrely, it even implied that the ECB should have cut rates if it really wanted to fight inflation, as a weaker euro might have led to cheaper oil.

This was reflexivity at its most deadly. Once the oil price had risen, whether for “good” reasons or bad, it had real effects on the economy and changed such crucial factors as the interest rates in the world’s two biggest economies. Traders bought oil as a sensible hedge against falling interest rates in the United States; but then they bought so much oil that they forced central banks to raise rates instead. Instead of hedging against a bad economic outcome, the rush into oil forced a serious policy mistake and helped to create an economic disaster.

Meanwhile, the other side of the trade, attacking banks, also reached the point of self-destruction. Selling banks short when they desperately needed new capital, much like buying oil to hedge against inflation, was a self-fulfilling prophecy. The latest institutions to fall into trouble were Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the pillars of the U.S. mortgage market. It was obvious that they did not have the capital to cover growing losses. They could not borrow more—that was how they had landed in trouble in the first place. But their falling share price meant that they could not raise equity either. Many banks held bonds or stock issued by Fannie and Freddie, so traders sold their stock as well.

In this way, the markets created a “reality” of spiking oil prices and failing U.S. financial institutions. But on Bastille Day, the “Sell Uncle Sam” trade collapsed under its own weight. It had never made sense, even if for a few months it had generated a lot of money. Now multiple actors in multiple markets across the world made sure that a new reality imposed itself.

In the first week of July, the ECB said it would not raise rates further, so the successful bid to bounce central banks into pushing up the dollar was no longer working. In the United States, on July 13, the government guaranteed the bonds of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. They would not be allowed to go under. Banks enjoyed a rebound.

Simultaneously, on the other side of the world, China sent terror through the markets by stopping its currency from rising. For the previous three years, it had allowed its currency, the renminbi, to rise gradually by 20 percent against the dollar in a managed and steady upward straight line. This redressed the global imbalances that so alarmed the U.S. without causing the disruption of a major currency crisis, and it also helped guard against Chinese inflation. But the Chinese suddenly decided to stop the renminbi from gaining against the dollar, while allowing it to keep rising against all other currencies, bar the Japanese yen.

All other things equal, this action would cause the dollar to rise—if it was pegged against renminbi, and the renminbi rose against the euro, then logically the dollar would do the same thing. And a rise in the dollar would reduce the price of oil, which must at this point have been crippling for Chinese industry, as oil and the dollar were in lockstep. Whether or not this was a deliberate aim of the Chinese authorities, a fall in oil price resulted, and their actions contributed to it.

With the authorities of Europe, the U.S., and China all apparently determined that the dollar should rise, on Bastille Day it duly did, leaping against all currencies bar the yen and putting at a disadvantage the many investors who had bet against the dollar by buying stocks outside the U.S. It kept gaining as that money came home to the U.S., and by the end of the year the euro had fallen from its lofty perch of $1.59 all the way to $1.25.

The rise in U.S. banks’ share prices and the gain in the dollar inflicted losses on investors who had piled into oil. And so, on Bastille Day, they took profits. With no news from the oil industry to push it, oil started a precipitate fall, dropping all the way to $35 per barrel by December. And extraordinarily, any trader who had kept on his “Bet Against Uncle Sam” trade of shorting U.S. banks and buying oil would have lost money for the year—despite the epic spike in mid-year, oil suffered a bigger fall for the year than did the shares of U.S. banks.

As the oil price tumbled, the market abruptly lost its fear of inflation. Faith in the BRICs, commodities, and “decoupling” went with it. The many traders who had survived the mayhem in the financial markets by betting on the BRICs were caught out and left sitting on losses. Deprived of what had been virtually the only way to make money in 2008, they had to embark on the painful process of “deleveraging”—selling what assets they could, to raise money to pay off their debts. That soon had its own devastating consequences.

In Summary

• Markets are reflexive—they can create their own reality.

• The run on the dollar and U.S. banks and the oil price spike of 2008 forced serious policy errors by central banks and forced governments across the world to respond.

• The spike was the result of moral hazard, cheap money, and hedge funds’ propensity to push trends too far.

• Lessons for the future are that the world remains on the “oil standard” and that rallies that so utterly contradict economic reality should be avoided.