Roughly speaking, any board or card game is a comparison of one object's properties and abilities with another. Let's take two cards; one is white and holds the number 1, the other is black and holds the number 2. If the most obvious rules are applied, the second card is more powerful, so it wins because two is greater than one.

This is the basis of a strategic game called Stratego (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stratego). It uses simple arithmetic comparisons to determine the winner of battle between two game pieces (each of them can represent soldiers, officers, or special items such as bombs). In most cases, the piece with a higher rank defeats its opponent; for example, a colonel, who ranks at 8 easily overpowers a sergeant who ranks at 4. The logic is pretty elementary and very descriptive, but it has not much intrigue as there are no unexpected turns. This problem can be fixed by introducing extra conditions that work on special occasions.

Let's return to our example with the two cards, the one with a lower rank can now win if you will add a new condition that says that a card painted with white defeats an opponent painted with black. Voila! The first card has suddenly won! In Stratego, we can find a real-life example of such scenario: the spy piece has the lowest rank in the game and is the most attackable figure, but it has a distinct advantage, the ability to attack and beat the marshall himself, which is the most powerful piece in the game! Here is the twist! In my view, the more unexpected layers and turns the game has, the more breathtaking it becomes. A player should feel secure, but he/she should not be opinionated. Of course, the game may have its own royal flush, but it should be very uncommon and hard to get.

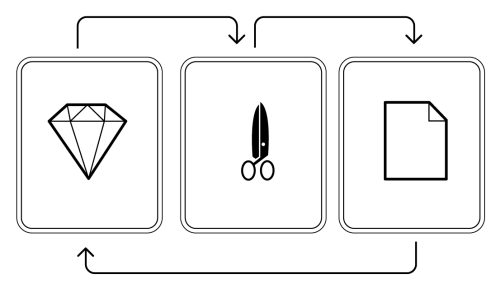

A wonderful example of balance based on the system of checks and balances is the immortal game rock-paper-scissors. It can easily be displayed by three cards: rock, paper, and scissors. So the player's armory consists of these three items. When the competition starts, all the players have to choose a card they think will be competitive and put it on the table simultaneously; then, the comparison process begins. Each card is powerful enough to defeat one of the cards from the deck but can lose to another. Thus, it has a potential chance either to win or to lose, and it all depends on the situation. The game can be tied too: if the competitive cards are equal. So, as you can see, there theoretically is no safe card in the deck and there is therefore always an element of suspense.

The important point is to note is that a player can try to read his opponents, trying to predict which type of card they will choose. This creates a basis for some psychological strategy rather than mechanical choosing of cards and this element makes the game more exciting.

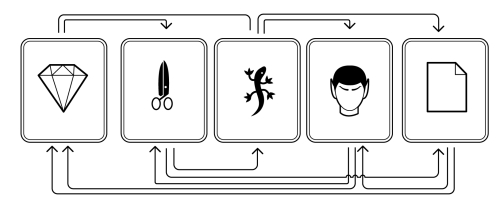

By default, rock-paper-scissors has only three elements to play with. Can its principles be scaled up for more elements? The answer, of course, is yes. There is a wonderful extension of the game, called rock-paper-scissors-lizard-Spock, which is played with five elements (cards, in our case). Although many people attribute the invention of this game to Dr. Sheldon Cooper from the amusing TV series The Big Bang Theory, where the game was mentioned several times, in reality it was created by Sam Kass with Karen Bryla (http://www.cafepress.com/samkass) long before the show was run. The rules of rock-paper-scissors-lizard-Spock are easy to remember and pronounce (try to make it fast):

- Scissors cut paper

- Paper covers rock

- Rock crushes lizard

- Lizard poisons Spock

- Spock smashes scissors

- Scissors decapitate lizard

- Lizard eats paper

- Paper disproves Spock

- Spock vaporizes rock

- Rock crushes scissors

Thus, each card can beat two specific cards and can lose to other two ones that are stronger than it. And this is not the limit; the boundaries of rock-paper-scissors can be expanded even more, and newer elements can make the game more exciting and surprising. David C. Lovelace, a freelance artist and flash animator tried to prove that by creating unusually large versions of the game. He started with moderate versions, including 7, 9, 11, 15, and 25 elements, inventing a lot of new hand gestures for the game: tree, water, lighting, and so on. But it didn't seem enough for him, so the hardworking inventor designed a rock-paper-scissors type of game with no less than 101 gestures! It took more than a year to finish the game, and the scheme of gestures looks like a big poster (http://www.umop.com/rps101.htm). Playing this game, you can be sure that your opponent's move will always be very sudden. The general problem of the game is a very complex table of rules and principles; it is very hard to learn and remember them. Therefore, it is hard to play it alertly with all the options in mind and with a conscious strategy. If the rules and number of elements is very large, most players use some random moves, relying on good luck or use a very small arsenal of cards.

A game like this printed on paper—in other words, in analog form—would be impossible to play because the dozens of elements and their interconnections are not easy to follow. But in digital form, all the calculations can be made without the player having to think and therefore, very quickly. All you need is a set of implications to compare the game pieces. In other words, dozens of if…then operators should be used, built upon your game rules.

So you see that the level of the game's unpredictability can be changed by increasing the number of game pieces, but this is a pretty extensive way of doing things, isn't it? What about more intensive approaches? No problem, all you need is to recombine some rules or add new components to the game. For example, a new version of rock-paper-scissors can be created that is played by two hands, and thus two cards can be used. For instance, the first card is for one turn only—the recurrent card—and should be taken from the deck each time, but the second one is in your inventory (the player can replace the recurrent card with one of the cards from the inventory). Otherwise, even a dice can be introduced to resolve tied situations in the game. What would you say about a special board game with some genes from rock-paper-scissors? Contrary to a classic game, where players can always choose the exact card they want, there is an element of fortuity here: at the beginning, the players have to take several cards from the deck and they are not sure what they will get. This creates room for new strategy. The game board is looped and can include special zones, where a player can change his current cards with new ones from a deck. When the player's game piece reaches the square already taken by the opponent's piece, a fight can start.

The players can choose and show their cards, playing a classic rock-paper-scissors match; the winner could get the game square. Then a main goal can be created; for example, players have to collect ten rock cards, which can be called precious stones. The cards for inventory can be taken on special treasure squares of the game board. We forgot about a pitfall, didn't we? Let's switch on our imagination! Here is a possible scenario: a pitfall can be generated by players by dropping some of their cards (in a case of a victory) on the game board to slow down their opponent. For example, there is a dropped paper card at the game square; if somebody reaches it, he should use his recurrent card and fight; if he loses, he cannot move for a turn. This creates a space for tactics. Of course, here it is only a concept, only an idea, but you can see that it is easy to develop a complex game plot even from a very general idea.