Traveling is one of the most memorable and exciting experiences a person can have. New discoveries, unusual details, and permanent surprises make you glad and happy. The life becomes so real and tangible. This is why adventure games will always be topical, since they let you travel in virtual worlds, evoking pleasant emotions.

Early prerequisites of adventure games can be found in postmodernist experiments with storytelling, which took place long before modern computers were born. Once writers understood that the structure of a book was not fixed, but could be very flexible, they were given a chance to create a new type of literature: non-linear stories with several plots. Readers only needed to get some new directions to work with chapters in a book; a new map to travel a book was required.

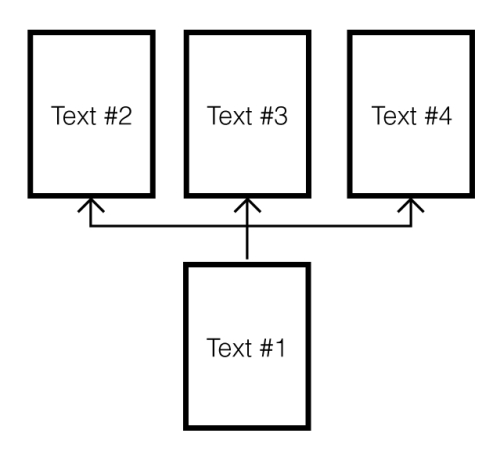

When you are talking about experimenting with a narrative, of course, the first name that comes to mind is that of the Argentine magician, a fabulous writer, Jorge Luis Borges. In 1941, he wrote a short story called An Examination of the Work of Herbert Quain where he talked about the literary heritage of a fictional novelist, who among others created a novel called April March. It featured a structure that can be called a tree of events. The plot can be constructed based on nine alternative beginnings that lead to a single finale. Thus, there were 13 chapters in that fictional novel with nine different versions of the beginning, three possibilities of intermediate events, and one finale. Jorge Luis Borges successfully demonstrated a model of a branch-based structure of the story.

The structure of chapters in April March – novel by Jorge Luis Borges

A similar notable example is that of Hopscotch, a novel by another Argentine genius, Julio Cortázar, originally published in 1963, featuring a very original concept. In this book, a reader may find 155 chapters, which can be considered as story blocks that let him construct two different plots. The first one can be attained in the simplest way by reading a portion of the chapters (from 1 to 56). The second one needs some additional efforts because the author included a special table of instructions in the beginning of the novel where a numbered sequence of chapters are displayed. The most intriguing part is the look of the sequence because the numbers were not chosen in a linear progression but by the author's special order creating an illusion of a mysterious code: 73-1-2-116-3-84-4-71-5-81.... Therefore, the second plot is figuratively hidden and can be found only by using the special key. By reading this book, a reader will travel from chapter to chapter, collecting a piece of the story and forming a whole picture of events.

Note

An interesting example of an experimental textual narrative is a book called Last Love in Constantinople (1994) by a Serbian novelist, Milorad Pavić, the author of Dictionary of the Khazars. This book was also made up of story blocks and required tarot cards instead of a special code to determine the further direction of the story and plot twists. Chapters had keys related to the cards since to construct the story you need to play the card game.

Postmodernist experiments later transformed into a separate class of fiction known as a gamebook, where readers could use their will (or good luck) to turn the direction of the stories. One of the legendary and popular names in that domain is a series of books entitled Choose Your Own Adventure based on a concept developed by an American writer, Edward Packard. In his novel, Sugarcane Island, he used some sort of interactive narrative, the readers had some options that lead them to different endings of the novel. The series was so popular among young readers that between 1979 to 1999, 184 titles were published by different writers; the overall number of copies printed was more than 250 millions. This is simply amazing!

How did the system work? Each page or individual chapter of a gamebook had a special section where several options were printed in a list. The reader just had to select the one that suited him the best, look at the specified number, and turn some pages to navigate to a chapter where the story continued according to his choice. The books featured multiple endings (up to a couple of dozens), had some objectives and RPG Mechanics, used a second-person perspective in their narrative, and were well illustrated. However, a wrong choice may lead a protagonist to death since they surely could be considered as prehistoric text-based adventure games.

The idea of interactive books was truly a breakthrough for its time. It changed the face of traditional media, creating a new image of a book as an object you can play with. But it also had obvious disadvantages. Navigating to a specific section of a paper book was not very convenient. It was not a smooth and instantaneous job (this is why they have a second version being republished in electronic form with real hyperlinks). Another weak point is that of easy access to any part of the book, so some elements could be intentionally peeped, spoiling the element of wonder.

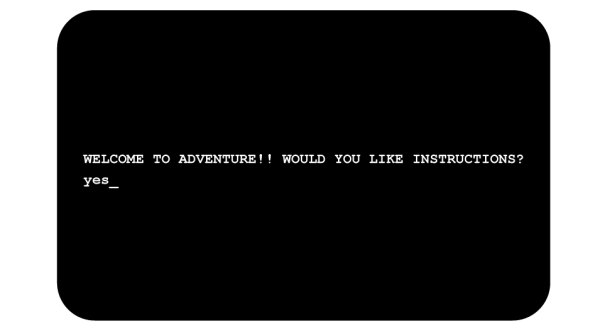

The full potential of interactive stories was exposed only on computers that simply made navigating much pleasant and added some functionalities which are simply impossible on paper. It happened in the middle of 1970s when William Crowther used 700 lines of the FORTRAN code to create Colossal Cave Adventure (also known as Adventure), a game that gave the name to the individual genre, which we are talking about in this chapter. By modern-day standards, that product was pretty simple. It had no graphics and used only text, but that was not the barrier for interesting gameplay. William Crowther was a cave enthusiast, so he carefully reproduced some real cave labyrinths (the original game included 140 map locations), adding some portion of fantasy elements.

The player got a textual description of a location or situation, then he could act by using one-or two-word directives in a form of verb-noun pairs, which were parsed by the game. It has 293 words in the vocabulary, since the game was capable to perceive and interpret a quite long list of player's commands.

An example of a text-based interface in an adventure game

Just imagine the enthusiasm of people who played Colossal Cave Adventure. In front of them was a gigantic computer with a small screen and green blinking letters, and inside that machine, a real, magical world with full of adventures and unknown discoveries was hidden. Imagination is an incredibly powerful tool. The walls of Colossal Cave's labyrinths had more details and seemed to be more realistic than any given modern game that is based on advanced 3D technologies and expensive artworks. So it is no wonder that soon William Crowther's creation got new talented followers: Colossal Adventure, Adventure Quest, Zork, and many others.

With the introduction of graphical interfaces and faster chips, a new era began. Adventure games started to explore the advantages of bitmaps. The paradigm was the same. A game pictured a scene, and the player entered a command trying to make the correct decision. One of the pioneers was Mystery House, an adventure game for Apple II, designed by a couple, Roberta and Ken Williams. The game was both inspired by Colossal Cave Adventure, which was accidentally founded by Ken Williams inside a catalog of a teletype terminal he was working with, and detective stories by Agatha Christie. Being an indie product by modern-day standards that was developed by enthusiasts, rather than a professional software company, the game surprisingly became a strong hit. The market welcomed it, expressing the idea that people desired this kind of electronic entertainment. They liked to take part in adventures and resolving mysteries. So the golden era of adventure games rose that would continue for almost two decades until the 2000s.

Roberta and Ken Williams soon founded a game company, which later became Sierra On-Line. It would publish many notable adventure games chaired by the King's Quest game series (because of its popularity, sometimes adventure games are referred to as quests). The world also saw masterpieces from LucasArts such as the Monkey Island franchise, the Indiana Jones game series, the Sam & Max game series, and many others.

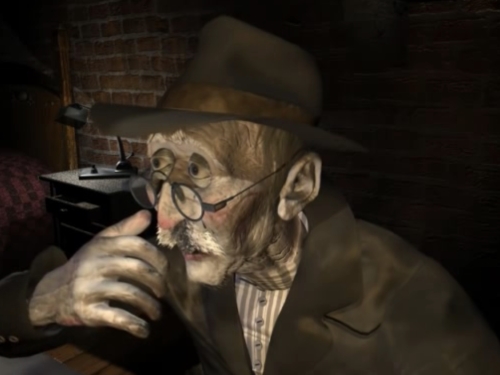

Amerzone – The Explorer's Legacy (1999) was the first graphical adventure game designed by Benoît Sokal

Adventure games tried to use the full potential of new technologies. The beginning of the CD-ROM era gave them a new energy, allowing the use of multimedia content to improve the quality of virtual worlds. For a period of time, they were considered as the most technically advanced genre in terms of video content, high-quality sound, 3D elements, and professional animation. The most important thing was that of game designers perceiving their creation as a very serious thing something close to films or good literature that required an excellent story and concept, interesting characters, intriguing turns, and very creative realization. Many of the games were simply, figuratively speaking, geniuses, for example, Blade Runner (1997) from Westwood Studios (a visual story and a masterpiece), The Last Express (1997) from Jordan Mechner (the creator of the original Prince of Persia), and The Neverhood (1996) from The Neverho od, Inc. (based on scenes totally sculpted from clay). One of my favorite projects of that period of time was Grim Fandango (1998) from LucasArts, which not only used a real-time 3D engine to draw character but also featured a perfect script and very smart dialogues. Developers were not afraid to explore boundaries of the genre making bold experiments with stories and visual look. In such conditions appeared stylish and surreal games such as Phantasmagoria (1995) from Sierra On-Line or amazing Sanitarium (1998) created by DreamForge Intertainment.

And after that the reality began to change. In the 2000s, the genre started to lose its popularity. Projects with big budgets more often became commercial failures, despite the fact that they were praised by critics. The golden era of adventure games came to an end. But this did not mean that such games disappeared from scene completely; they simply turned into a less mainstream product. For instance, many interesting projects were created under the French software brand Microïds that is mainly associated with name Benoît Sokal, a talented illustrator and game designer, who created the critically acclaimed game series, Syberia (2002 to 2004). These games represented the technical direction chosen by authors of interactive adventures in that period of time. They used fixed camera angles, prerendered static images to create an environment, videos to animate some elements, and a real-time 3D engine to drive characters. All those things together created an excellent visual presentation. Such an approach was referred to as 2.5D graphics.

The first part of Syberia was successfully ported to iOS devices

Nevertheless, in the second part of the 2000s, part of the new titles were less intriguing and artistic than their predecessors. The gameplay turned into something mechanical; scripts were not very exciting and the ideas were not so inspiring. The genre was in a creative crisis. A way out was founded by enthusiasts, who began to design so-called author's adventures.

The games were created by individuals not because of desire to get strong profit but to tell their own stories. They needed self-expression via interactive fiction. Such games used free engines such as Adventure Game Studio (http://www.adventuregamestudio.co.uk/) or Wintermute Engine Development Kit (WME) (http://dead-code.org/home/). Some of the designers also used Adobe Flash because of the flexible nature of this technology and the simplicity of distribution of the final product; the author simply had to put the game online. A wonderful example is Samorost (2003), a surreal puzzle-adventure game designed by a Czech student Jakub Dvorský, which could be considered as a real piece of modern art. Later its author found an independent game studio called Amanita Design. In 2009, it produced another gem, a game that can be marked as one of the most beautiful adventure projects of the decade, Machinarium. The key of success was based on its engrossing story, charming mood, and the incredible drawings of a talented Czech graphic artist, Adolf Lachman (http://adolflachman.cz/machinarium/). The game was rewarded with many awards and nominations: Aesthetics award at IndieCade (2008), Excellence in Visual Art award at the 12th Annual Independent Games Festival, and so on. It achieved a huge fan base being ported on various platforms, including iOS. The most important fact is that Machinarium was an indie project. The game was not produced by a gigantic corporation but by a small team of people who liked to tell stories via games. The studio didn't even have much of funding to work on the project; developers used their own savings. This is why it is a very inspiring story!

Machinarium is real masterpiece, created by Amanity design.

The genre got a second breath with the introduction of modern smartphones, especially tablets. In contrary to computer systems and gaming consoles, they were more likely to harbor those types of games, letting players have direct contact with the game environment. This is why there are adventure games on iTunes. Moreover, many old titles were successfully ported on the new platform, enriched with some remastered assets and featuring improved graphics and sound. For example, the first two parts of the legendary adventure game series Broken Sword from Revolution Software, The Last Express, Amerzone: The Explorer's Legacy, and many others.