Creating a character is not an easy job, it can be done by creative insight or careful calculation. The main hero is the soul of the game and whose avatar is used by a player to explore the game world. Players identify themselves with that picture on the screen, empathizing with it, enjoying, grumbling, and taking all the situations to heart. Therefore, the objective is to generate an emotional connection between the character and the player. It is not necessary to provoke only positive feelings; ironically, sometimes the player can hate his avatar. A graphic look of the character can induce a wide spectrum of emotions, and these emotions can be calculated in advance. This is based on the fact that humans usually have nearly the same reactions; in this case, the rules of their behavior are pretty conspicuous.

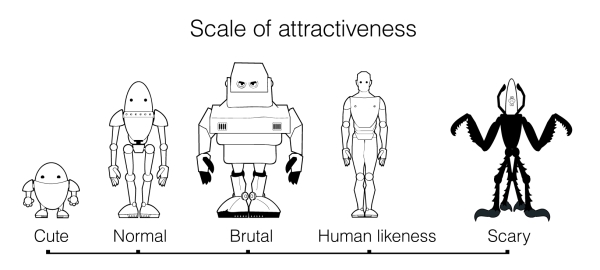

To illustrate the principles, I created the Scale of attractiveness , made of four main entries. At the very left, there is the Cute mark, in the middle is Brutal , followed by Human likeness , and to the right we see Scary . So, the chart begins with something very adorable and sweet but end with a scary character. Each position has its own collection of qualities.

Cuteness is one of the most popular and demanded features that game designers want for their creations. Protagonists of majority casual games are cute to some degree; they look and act as sweet and comely creatures. It is simply impossible to ignore them and not fall in love with them. Recall the famous image of Nintendo's Mario, he is 100 percent cute. What is the secret of such popularity? First, the cuteness is not about beauty (it is hard to call an alligator's baby truly attractive, but it definitely is cute), which depends on personal taste and preferences, but about some basic patterns and proportions. Here is a citation from Natalie Angie's article The Cute Factor published in The New York Times:

"Scientists who study the evolution of visual signaling have identified a wide and still expanding assortment of features and behaviors that make something look cute: bright forward-facing eyes set low on a big round face, a pair of big round ears, floppy limbs and a side-to-side, teeter-totter gait, among many others."

All listed features are general descriptions of one class of creatures on Earth: little babies and cubs. They are small, their heads are noticeably bigger than their body, their limbs are short, eyes are large, and so on. When we see something like that, a special system inside us tends to react commonly. It says that probably in front of us is a defenseless young creature that needs protection, care, and tenderness; a list of positive senses is switched on. Figuratively, we are filled with light.

By introducing a cute character in a game or other media, the authors simply exploits one of the natural human reactions. This is possible because it is pretty unconditional, the brain only needs some basic patterns, and the factual meaning of an object is totally irrelevant in this case. Thus, we consider something as cute despite the fact it is not a baby at all. Kittens are super cute, but adult cats can be cute too because they are small, have round and smooth bodies, and big eyes. Another popular example is owls, they have big round heads and large expressive eyes, making them one of the cutest birds on the planet.

Moreover, some mechanical objects are cute as well: majority European compact cars from the 1950s are adorable, remember the BMW Isetta, Fiat 500, original Mini, and VW Beetle? All of them look so nice and sweet, that you want to hug them, cover them with a plaid, and give some milk in a plate, as though they are small mechanical babies of bigger adult cars. The industrial design in that period was inclined toward cuteness (may be it correlated with the baby boom). Even utility vehicle such as buses and trucks were cute, in addition to household devices such as radio sets and refrigerators. But the most amazing thing was cute weapons. Of course, I'm not talking about the real ones, but imaginary ray guns that appeared in sci-fi art and in the form of toys were definitely adorable. It is clear why illustrators prefer to use objects from previous decades in their pictures, the final illustrations look warmer.

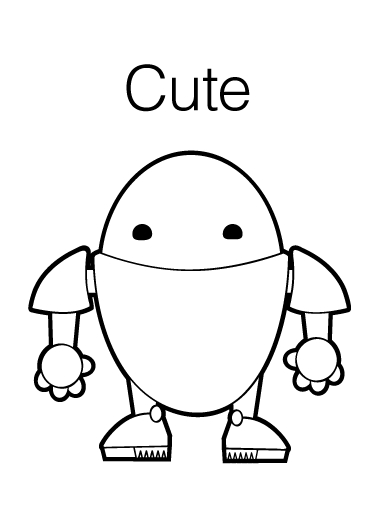

Therefore, to create a cute character, you need to follow some evident visual rules:

- Short body

- Rounded angles

- Curved contours and chubby figures

- Smooth surfaces without folds and wrinkles

- Big head with large forehead and small low jaw

- Small mouth and teeth

- Large eyes (or they stand wide) with big pupils

- Wide-open eyes with eyebrows lifted up

- Animals with big nose

- Short arms, legs, and fingers without visual joints

Generally, cuteness is necessary for a protagonist to have a corner in the player's heart. An antagonist must give birth to opposite feelings: loath and fear. Good enemies are creepy characters. To choose their visual appearance, let's again exploit some ancient mechanics from the human brain. There are a lot of alarm systems that alert us when something looks or behaves suspiciously. Deep-seated fears of various forms are inside most people. A game, of course, should not provoke a real panic action, but can tickle some sensitive zones, playing with associations. Creepiness is the complete opposite of cuteness, it gives not a feeling of warmth, but that of cold.

To find an effective scary factor, it is good to look at common fears. Traditionally, many people try to avoid insects or even have phobias. Attributes of such creatures are interpreted as unpleasant or frightening. The only exception is ladybugs (they are round with white dots on their head and large eyes) and butterflies, which are primarily associated with petals of bright flowers. It is important to note that in most cases, insects are not aggressive and harmful, but they remind us of creatures from our worst nightmares, giving us the creeps (few examples are mole crickets and earwigs, eek!) Besides them, there are other types of arthropods with high potential of creepiness (and some of them are really dangerous!): spiders, scorpions, and centipedes.

They have adverse visual features such as jointed legs, spikes, exoskeletons, tails, multiple eyes, mandibles, and pincers. The key visual element is a gad, associated with cuts, injuries, and so on, that contradicts a cute creature's properties, which has no acute angles. Moreover, fishes, reptiles, birds, and mammals look dangerous when they show their teeth, canines, tusks, horns, clutches, or sharp beaks. A predator is frightening because it shows it threatens with its weaponry: the potential danger is pretty obvious and their current intention is questionable. Now, the eyes comes into play. If they are fixed at you and are not blinking, it is most likely that the predator is paying attention to you and that is super scary. Furthermore, the eyes can be red because the reflection of light creates such an image. Dangerous creatures are fast so they can move and attack quickly; this means their limbs are pretty long, but bodies are narrow and streamlined. The following figure shows a scary creature:

Besides aggressive elements, other unpleasant properties can be used to increase the emotional impact; for example, the character can be additionally disgusting if it is covered with strange skin and even mucus. That turns on the dread of biological substances and the fear of germs and parasites. Squeamishness is one of the protection systems of a human, and sometimes it is very unconditional. Such an approach was used in Ridley Scott's science fiction classics Alien: apparently the xenomorph was inspired by various creepy creatures, including arthropods and reptiles.

In addition, it had a very disgusting feature: toxic saliva was always dripping from his mouth, causing the viewers to feel terror and revulsion, a doubled negative emotion.

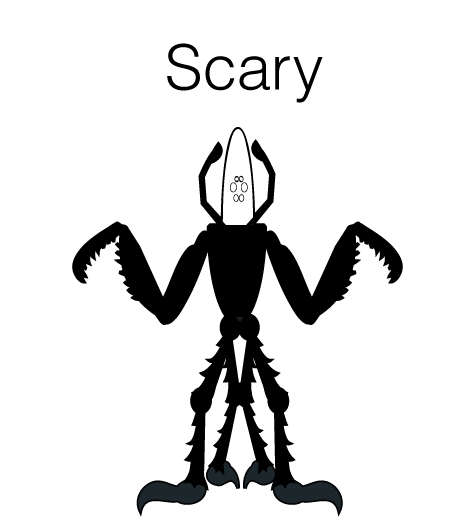

While creating a scary character, remember some basic features it needs to express through its design:

- Long and skinny body

- Nonhumanoid structure

- Many angles

- Many legs or at least noticeable joints

- Acute elements, such as spikes, clutches, and horns

- Small head

- Naked eyes that stay very close and can be red

- Weaponry openly displayed (biological tools such as pincers, real guns, and grenades)

- Unpleasant skin with verruca, folds, wrinkles, and some mucus

- Warning color that can mean that the character is venomous

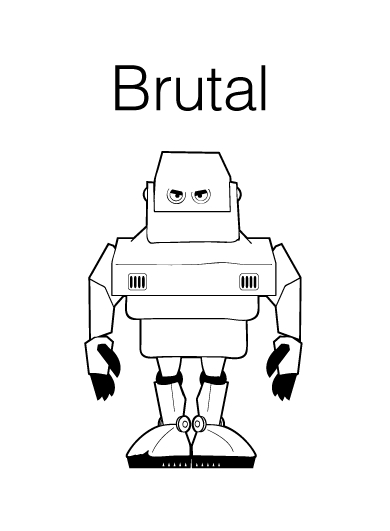

Brutality, at the middle of the scale of attractiveness, describes the properties of a character that should exercise some heroic duties, being a soldier or a mercenary. It is obvious that such a person cannot have cute characteristics, otherwise it would look comical. Adorable creatures are associated with something very young, but the heroic character should be an adult. He must demonstrate strength and confidence with a little aggression. So, his look should be a little scary, but only a little, as far as he is not a creepy creature from the end of the scale. Since the brutal hero performs various acts of bravery, he must be fast and agile. So, his anatomical proportions should be close to hyperbolic athletic ones like heavy action heroes from the 1980s, featuring a well-developed muscular system and military toys. The following figure shows such a heavy action hero:

The apparent illustration of a brutal character is Duke Nukem, a protagonist of the game series of the same name originally developed by Apogee Software. He is brutal and fearless, and definitely not cute. A bunch of good examples is included in the game Gears of War from Epic Game s. The members of Delta Squad are canonically brutal and tough guys.

Such type of characters generally are used in action games such as shooters. Figuratively speaking, they are mix made of a human and an armed vehicle, since they hold heavy weapons and armor. The following are the basic visual properties of such a hero (it is important to note that the brutality is gender independent, and although many such characters are men, nobody has forbidden you from creating a strong woman protagonist):

- Figures with no acute angles or rounded corners, but ones that are roughed down

- Strong legs

- Heavy feet to lean on the ground reliably

- Big hands with tenacious fingers to hold weapons and other objects

- Wide chest with ram-like powerful shoulders that are bigger than the legs

- Normal head with mid-sized forehead and a big low jaw

- Naked big eyes

It is pretty apparent that the extreme position on the scale is too categorical a benchmark to follow, whereas in most cases, nobody needs super cute or extremely scary characters. Something more universal is a mix of different properties, which is far more expressive. It is interesting that, as a rule, designs of a protagonist are situated between cuteness and brutality, so the character is anatomically adapted to make complex actions: move fast, climb ladders, fight, among others, and at the same time being pretty attractive.

Did you note that, on the scale, there is a mark named Human likeness, which is placed after the brutality? What is surprising is that it is closer to the scary section than the pleasant cute one. Why does the realistic look of a human being have scary connotations? The answer is interesting. We, as humans, are very familiar with the visual appearance of people around us. Our vision knows everything about natural proportions and other graphic features. All these properties are thoroughly learned through everyday experiences of communication with real people. Since it is very easy to sense a catch or when a figure is pretending to be real, it must be ideally crafted to look natural. Any minor mistake would be easily noticed by viewers.

Moreover, the brain apparently does not particularly say that, for example, the arms are too short for a figure of a specific height or the mouth is too big. It simply transfers a generalized signal that something is wrong. In addition, by looking at somebody's image, we try to read their emotions by using empathy that helps us to determine the emotional state of another human and predict the possible intentions. Now, imagine a situation: there is a character, which is pretty realistic by basic attributes, but subconsciously, we feel that something is wrong, not knowing the actual reason. The effect is stronger if the character is moving and his motility is not perfectly realistic. The empathy system experiences some troubles. As a result, we sense that in front of us is a strange person whose image and behavior is a little bizarre, so it is better to be on the alert. Such a sensation confuses us and the emotions received are not pleasant and comfortable, although they are not very strong and long termed. They mostly consist of distaste, rather than fear.

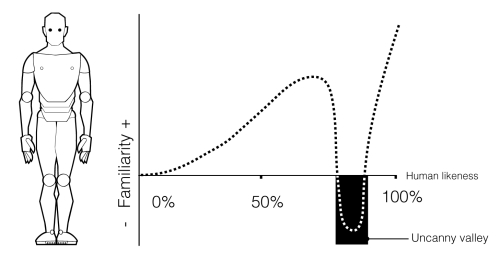

This effect is known as the uncanny valley hypothesis. The name is taken from a description of a graph, showing a relationship between human likeness of various humanoid images and the emotional reaction of the audience to their look. Normally, the emotional response is positive and it increases with the degree of visual likeness. The values are proportional, and suddenly when the likeness is high enough (around 70 percent), but not yet equal to 100 percent, the response abruptly falls down, forming a valley on the graph. There are negative reactions gathered in the valley, which is why it was called uncanny. The audience will only change its mind and begin to have positive feelings when the degree of human likeness approaches somewhere close to 100 percent. The theory was developed by Japanese roboticist Masahiro Mori in 1970. He researched the emotional impact of humanoid robots on people.

There are several theories about the origin of the uncanny valley. For example, some opine that it is caused by an ancient alarm system that keeps us away from bizarre strangers, giving us a cue that they were hiding something. Their peculiar look could mean that they had some form of dangerous diseases, and unusual behavior may indicate that their intentions were unclear and possibly dangerous too. So, the theory is based on odd and confusing feelings, which are caused by some sort of uncertainty. There are many contradictory sensations and a person feels trapped. In folklore and popular culture, such experiences are connected with bewitched persons, the walking dead, humanoid aliens, revived mannequins, or statues.

Despite the uncanny valley primarily described as the human perception of robots, it can be effectively applied to other media. May be you empirically formulated this theory while having some weird experience when watching CGI animations, which utilize realistic portrays of human beings. 3D models are so well crafted that you see individual pores on the characters' skin and the movements are realistic because they are provided by accurate motion capture technology, so you notice every tiny inconsistency. It is hard as authors try to convince the audience that the picture is equal to live action; this does not work. Moreover, the characters look a little bit repulsive. Many illustrators, animators, and toy designers know about this factor, therefore, they always try to rethink human proportions. Recall all of Pixar's characters, they are all far away from the uncanny valley, even from a small uncanny pit. My favorite example is Carl Fredricksen from the animated feature Up. This was a very nontrivial task to make an old person look cute, but they successfully did it, giving it a big square head, a small body, and short arms, which are not close to real human anatomy. Apparently, this is why in James Cameron's movie Avatar, a special stylization was used for the Na'vi characters—which were fully CGI and animated using advanced motion captures—by giving them different proportions such as cat-like eyes and unusual skin color; the crew defeated the uncanny valley.

Now you know that a realistic proportion is a tricky business. You can use it only if the quality of the image and animation is almost ideal. In other cases, it is always better to break the realistic anatomical dimensions and apply hypertrophic characteristics to some features or details. As a rule, protagonists in games are vertically compressed, have big heads, short torsos, noticeable feet (heavy shoes), and so on. Besides the artistic expressiveness, there is a practical reason for nonrealistic look being preferable: a figure with natural proportions is too high to depict fully. You need to scale it down to fit the game world. So all its tiny details disappear from the scene, and as results, you get a small and skinny character. This is especially topical for platformer games, as characters are displayed sideways.

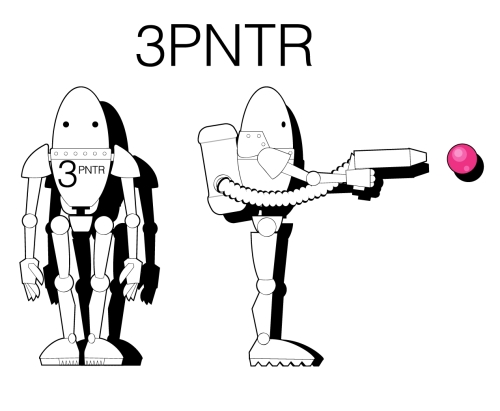

3PNTR, the protagonist in our game, should run and jump and carry an improvised gun, since his anatomy must correspond to the given tasks. The legs and arms should be long enough, but he also needs to be cute; as long as the style of the game is rather comical than realistic. So, his head is big and looks like a glass blister and the eyes are dots, placed far apart from each other. As shown in the following figure, a funny characteristic of his head is that it hides a little bit in the body, like in a turret. Behind the back is a cylindrical tank for paint, connected to the gun with a hose.

The tank can change its color, showing the type of paint inside. Alternatively, it can have special windows on each side, but that can be difficult to implement because of animation. However, you give the tank a specific tint using code. The character carries the number 3 on his chest as it is his individual index—he is the third robotic painter.

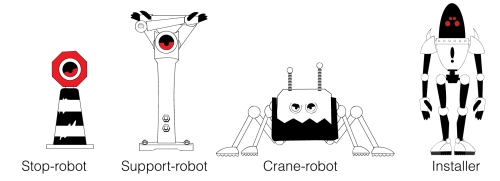

All enemies are utilitarian robotic devices that are used in construction, few of them are humanoids. Some of them cannot even move and play the role of fencing or support. Nevertheless, they have eyes and an electronic brain, and can attack the protagonist with a painful electric discharge. A movable enemy tries to follow and attack the protagonist. The following figure shows various types of enemies:

The following is the short list of enemies:

- Stop robot: It is a static creature that looks like a striped pole with the Stop warning sign and plays the role of an obstacle.

- Support robot: It is a creature that cannot move and plays the role of an obstacle. It supports a platform above, so by removing such a robot from the scene, the player can also demolish some parts of the level.

- Crane robot: It can move horizontally and looks like a crab, walking on four legs.

- Welder: It is a dangerous robot that operates like the crane robot, but also has a scorpion-like tail with an electrode at its end. It cripples the protagonist stronger than the previous mentioned robots.

- Installer: It has humanoid anatomy, so it moves fast and in every direction. It follows the main character and is harder to escape.

- Virus-affected CPU queen: It is the final boss of the game.

Recall the negative feedback paradigm? It tells the player that enemies become stronger as the game progresses and acts like a training that player get while playing. Only Stop robots and Support robots first appear, followed by Crane robots, and finally come the Welders and Installers. It is important to note that not only does the strength of a particular opponent play a major role but also the number of opponents. A Support robot can be weaker than the protagonist, but three of them fighting together are much stronger. So, by introducing new types of robots and increasing their numbers on the screen, a game balance can be adjusted to a specific difficulty level.

It is also important to not forget the asymmetrical balance: opponents should not be exactly equal to the protagonist. Some of them should move slower, but have stronger weapons, while some others can run quickly, but their armor is stronger, and so on. This how fighting sequences should be made to ensure that they are more catchy, because players must use different tactics to attain victory. Apparently, it is hard to develop an accurate and universal formula that can help to calculate the distribution of a character's features; thus, many real playtests are needed to ensure that the values are correct.

Also, it is difficult to create a new design and look for each new type of enemy. But there is a simple trick that many developers use: regular enemy characters can be declared as more stronger units by saying that they are armored. In this case, only some minor changes in their image are made to designate that they are wearing some armor.