A Framework for the Investigation and Modeling of Online Radicalization and the Identification of Radicalized Individuals

Petra Saskia Bayerl1, Andrew Staniforth2, Babak Akhgar3, Ben Brewster3 and Kayleigh Johnson3, 1Erasmus University, Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2North East Counter Terrorism Unit, West Yorkshire Police, West Yorkshire, UK, 3Sheffield Hallam University, Sheffield, UK

In this chapter we present an empirically-based theory-independent framework of online radicalization. The framework provides a systematic basis for (a) the representation of causal mechanisms of online radicalization and (b) the identification of radicalized individuals. Its application lies in informing models of online radicalization, guiding the formulation of policies, and identifying gaps in our current knowledge of online radicalization.

Keywords

online radicalization; identification of radicalized individuals; behavioral indicators; causal relations; theoretical framework

Information in this chapter

Introduction

On May 22, 2008, British citizen Nicky Reilly made his way to the Giraffe restaurant in Exeter, South England, with a rucksack containing six bottles full of nails and home-made explosives. He ordered a drink and then made his way to the lavatory, taking his rucksack with him. There the device detonated prematurely. None of the 44 guests present was injured, but it damaged the restaurant and caused injuries to Reilly. A note left at his home revealed his actions as a tribute to Osama bin Laden and declared that violence would continue until “the wrongs [done by ‘the West’ to the Muslim world] have been righted.” Appearing at court as Mohammed Abdulaziz Rashid Saeed, Reilly pleaded guilty to offenses of attempted murder and preparing for acts of terrorism and was subsequently sentenced to life imprisonment. While the actions of Reilly were clearly abhorrent, many would come to view him as a victim of terrorism himself. Recruited online in chat rooms, extremists had molded a home-grown terrorist, had directed him to bomb-making websites, and had discussed what his target should be. Reilly became, if not an outright victim, then at least an instrument to serve the terroristic purposes of others, manipulated by anonymous terrorists online.

The threat from contemporary terrorism is both serious and enduring, being international in scope and involving a variety of individuals, groups, and networks that are driven by extremist beliefs. No country, community, or citizen should consider themselves immune from the global reach of international terrorists who believe they can advance their political, religious, or ideological aims through acts of violence. Tackling the terrorist threat remains a national security priority for many governments across the world.

In this context, online radicalization has become a pertinent issue. As the introductory example demonstrates, the Internet has changed—and continues to change—the very nature of terrorism [1]. The Internet is well-suited to the nature of terrorism and the psyche of the terrorist. In particular, the ability to remain anonymous makes the Internet attractive to the terrorist plotter [2]. Terrorists use the Internet to propagate their ideologies, motives, and grievances. The most powerful and alarming change for modern terrorism, however, has been its effectiveness for attracting new terrorist recruits, very often the young and most vulnerable and impressionable in our societies. Modern terrorism has rapidly evolved, becoming increasingly non-physical, with vulnerable “home-grown” citizens being recruited, radicalized, trained, and tasked online in the virtual and ungoverned domain of cyberspace. With an increasing number of citizens putting more of their lives online, the interconnected and globalized world in which we now live provides an extremely large pool of potential candidates to draw into the clutches of disparate terrorists groups and networks [3].

The indoctrination of our citizens by online radicalizers and recruiters is a pressing concern for all in authority. The Internet has become crucial in all phases of the radicalization process, as it provides conflicted individuals with direct access to unfiltered radical and extremist ideology, which drives the aspiring terrorist to view the world through this extremist lens. When combined with widely marketed images of the holy and heroic warrior, the Internet becomes a platform of powerful material, communicating terrorist visions of honor, bravery, and sacrifice for what is perceived to be a noble cause [3].

The prevention of online radicalization remains an ambitious undertaking, and still we must find new and innovative ways in which to expose and isolate the apologists for violence, and protect the people and places where they operate. Intelligence and law enforcement agencies across the world have come to learn more about how the processes of radicalization develop, but their collective understanding remains far from perfect. If preventive measures are to have a chance in interdicting at least the most savage excesses of online extremism, counter-measures need to be informed by better definitions of online radicalization and improved modeling of its causal mechanisms. The framework outlined in this chapter provides intelligence and law enforcement agencies with a structured framework for the investigation and modeling of online radicalization. It further provides a systematic approach for the identification of individuals radicalized online to support the prevention of terrorism and violent extremism.

In addressing the security challenge of online radicalization, the objectives of our framework are two-fold:

1. Provide a systematic basis with which to model causal mechanisms of online radicalization in the form of an Radicalization-Factor Model.

2. Provide an approach for the empirically derived identification of radicalized individuals based on behavioral indicators.

Its application is intended to support the following functions:

• Inform the choice of concepts and evaluate the completeness of modeling approaches: The quality of modeling approaches relies on the correct and complete choice of concepts. Our framework provides a matrix covering all relevant aspects pertinent to online radicalization. This matrix can be used to inform the choice of factors and judge whether all pertinent areas are included in the model.

• Represent interactions of disparate factors within a common framework: Considerations of online radicalization tend to focused on only a specific set of factors. Our framework creates a common matrix to raise awareness about and represent the interconnectedness of causal factors.

• Support analysts in devising strategies to detect and prevent radicalization by providing guidance on the factors that are shown to enhance or discourage it: Models based on our framework provide analysts with structured guidance on which areas to target for detecting and preventing online radicalization and radicalized individuals, especially in advocating a clear operationalization of behavioral indicators.

• Provide a roadmap to indicate gaps in our knowledge on online radicalization: Inserting known factors into our framework, the matrix provides a systematic view on factors and their relationships under-represented in the current work on online radicalization.

Systematic consideration of influencing factors: The radicalization-factor model

Nobody suddenly wakes up in the morning and decides that they are going to make a bomb. Likewise, no one is born a terrorist. Conceptualizations of radicalization have increasingly recognized that becoming involved in violent extremism is a process: it does not happen all at once [4]. Similarly, the idea that extremists adhere to a specific psychological profile has been abandoned, as has the view that there may be clear profiles to predict who will follow the entire trajectory of radicalization [1].

Instead, empirical work has identified a wide range of potential “push” and “pull” factors leading to (or away from) radicalization. This starts with the fact that terrorist groups can fulfill important needs: they give a clear sense of identity, a strong sense of belonging to a group, the belief that the person is doing something important and meaningful, and also a sense of danger and excitement [4]. For some individuals, and particularly young men, these are very attractive factors. At-risk individuals share a widely held sense of injustice. The exact nature of this perception of injustice varies with respect to the underlying motivation for violence, but the effects are highly similar [4]. Personal attitudes such as strong political views against government foreign policies regarding conflicts overseas can play an important role in creating initial vulnerabilities.

Terrorism is a minority-group phenomenon, not the work of a radicalized mass of people [1]. People are often socialized into this activity, leading to a gradual deepening of their involvement over time [4]. Radicalization is thus a social process, which requires an environment that enables and supports a growing commitment. The process of radicalization begins when these enabling environments intersect with personal “trajectories,” allowing the causes of radicalism to resonate with the individual’s personal experience [1]. Some of the key elements in the radicalization process are thus related to the social network of the individual (e.g., who is the person spending time with, and who are his or her friends?) [4].

As this short overview demonstrates, past research has identified a wide range of influencing factors. Still, despite an impressive amount of work on radicalization, consensus on the process and the relevant factors leading to online radicalization, or radicalization more generally, remains elusive [5]. Moreover, existing theoretical models use disparate lenses and mechanisms to explain why (online) radicalization takes place in some people and not in others (e.g., [6–8]).

For this reason we argue for a theory-independent approach that enables the aggregation of empirical findings into a common framework. We suggest the Radicalization-Factor Model (RFM) as such a framework that allows the integration of known causal factors on online radicalization.

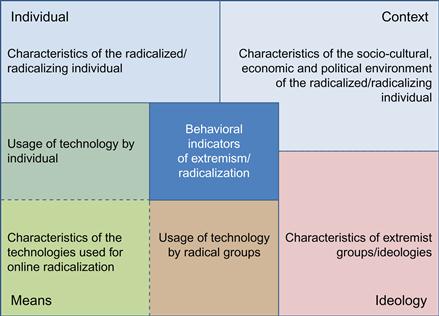

The model considers four interlinked factors:

1. Characteristics of the radicalized individual: This aspect refers to features of the individual that are linked with a weaker or stronger vulnerability for radicalization in general or a preference for specific ideologies as well as specific patterns of online and radical behaviors. These can include aspects from demographic information to norms, values, or personal experiences.

2. Characteristics of the environment: This aspect refers to the environment(s) in which not only the individual, but also the ideological groups, operate. The environmental(s) can be analyzed with respect to political, economic, social, technological, and legal characteristics (political system, societal diversity, general level of education, religious observance, Internet penetration rate, legal system, etc.).

3. Characteristics of the radical groups and ideologies: Terrorism comes in many forms based on political, religious fundamentalist, nationalist-separatist, social revolutionary, and extreme right-wing ideologies [9]. Other typologies of terror include state-sponsored terrorism and single-issue terrorism; the latter very often committed by the lone actor or “lone wolf” terrorist [10]. Identifying the specific genre of terrorism is an important factor in determining the most effective counter-measures to deploy.

4. Characteristics of the technologies related to online radicalization: Technologies differ greatly in the extent to which they may lend themselves for online radicalization or for terroristic behaviors (indicators). Relevant aspects are here, for instance, the degree of anonymity for users, the speed with which information can be send/accessed, or the number of users to be reached at the same time.

RFM further includes the usage of technologies by the individual as well as the usage of technologies by the ideological group(s) the individual belongs to or is influenced by. These two aspects consider inter-linkages between technology (factor 4) and the individual (factor 1) and radical groups (factor 3), respectively. With this, RFM allows to represent knowledge about specific online behaviors increasing or decreasing radicalization (e.g., radicalizing individuals tend to exclusively access networks that adhere to their own ideology, which, in turn, leads to exaggerated views of public support for their own view [11]). In including technology features as well as technology usage patterns, our framework thus explicitly addresses the context of online radicalization.

The complete Radicalization-Factor Model (RFM) is presented in Figure 33.1.

Identification of radicalized individuals: Behavioral indicators

While RFM provides the matrix to outline the causal pathways toward online radicalization, a second crucial element is to clarify what online radicalization and radicalism exactly entails. In our view, without a clear definition, it is impossible to unequivocally link influencing factors to online radicalization. Further, only with a clear view on which behaviors can serve as indicators is it possible to identify radicalized (or radicalizing) individuals. Such conceptual clarity is also relevant to allow differentiation between radicalized individuals, who may pose an actual/acute threat, from mere sympathizers. Of course, the transition from sympathizer to active terrorist is not a distinct step [12]. Still, omitting the specification of clear criteria can result in a dangerous blurring of the concept and thus increase the risk to unsystematically expand the group of targeted individuals (risk of false positives). Moreover, the clear specification of indicators enables the comparison of definitions of online radicalization as well as comparability of empirical results. Therefore, a precise operationalization of online radicalization is needed in every application case.

We propose three ways of operationalizing online radicalization/extremism:

By “behavioral indicators” we refer to the concrete behaviors of a person, which indicate that he or she has been radicalized.

Single behavioral indicators

Some behaviors are very clear and can by themselves indicate radicalization. Such single indicators are best defined as online behaviors that crossed the legal threshold; that is, the individual has committed criminal acts of inciting racial hatred and violence, encouraged terrorist activity, or is directly concerned in the commission, preparation, or instigation of acts of terrorism. If a person shows one of these behaviors, it can be assumed with some certainty that radicalization has occurred. To illustrate, consider the following example:

When UK counter-terrorism police officers raided a flat in West London in October, 2005, they arrested a young man, Younes Tsouli. The significance of this arrest was not immediately clear, but investigations soon revealed that the Moroccan-born Tsouli was the world’s most wanted “cyber-terrorist.” In his activities, Tsouli adopted the user name “Irhabi 007,” (Irhabi meaning “terrorist” in Arabic), and his activities grew from posting advice on the Internet on how to hack into mainframe computer systems to assisting those in planning terrorist attacks. Tsouli trawled the Internet, searching for home movies made by US soldiers in the theaters of conflict in Iraq and Afghanistan that would reveal the inside layout of US military bases. Over time, these small pieces of information were collated and passed to those planning attacks against military bases. This virtual hostile reconnaissance provided insider data, illustrating how it was no longer necessary for terrorists to conduct physical reconnaissance if relevant information could be captured and meticulously pieced together from the Internet. Police investigations subsequently revealed that Tsouli had €2.5million worth of fraudulent transactions passing through his accounts, which he used to support and finance terrorist activity.

Pleading guilty to charges of incitement to commit acts of terrorism, Tsouli received a sixteen-year custodial sentence to be served at Belmarsh High Security Prison in London where, perhaps unsurprisingly, he has been denied access to the Internet. The then National Coordinator of Terrorist Investigations, Deputy Assistant Commissioner Peter Clarke, said that Tsouli “provided a link to […] the heart of al Qa’ida and the wider network that he was linking into through the Internet […]what it did show us was the extent to which they could conduct operational planning on the Internet. It was the first virtual conspiracy to murder that we had seen.”

Tsouli exhibited a range of behaviors that clearly demonstrated the high degree of his involvement in terrorist activities, from providing information to assist in the planning of terrorist attacks to their financial support. Any one of these behaviors constitutes a single behavioral indicator for radicalization.

Combinations of behavioral indicators

Other behaviors are less clear; for example, reading radical blogs can come from different motivations (a person is studying the topic for a high school paper, may simply be curious, or indeed be trying to obtain access to a radical group). Some behaviors are thus not unambiguous enough to identify online radicalization. In this case, a combination of specific behaviors (i.e., two or more actions occurring together) may still provide a clear indication that radicalization is taking or has taken place.

In June of 2006, Hammad Munshi, a 16-year-old school boy from Leeds, United Kingdom, was arrested and charged on suspicion of committing terrorism-related offenses. He remains the youngest person in Europe to be formally charged and convicted of terrorist offenses. Following his arrest, police searches were conducted at his family home, where his wallet was recovered from his bedroom. It was found to contain hand-written dimensions of a sub-machine gun. At the time, Munshi had excellent information technology skills; he had registered and run his own website on which he sold knives and extremist material. He passed on, for example, information on how to make napalm as well as how to make detonators for improvised explosive devices (IED). At the time of his arrest, Munshi was still a schoolboy and had been directly influenced by being exposed to extremist rhetoric and propaganda on the Internet from the comfort of his bedroom, unbeknownst to his family, friends, and wider social network.

While the individual actions by Munshi certainly are problematic, in this case the full degree of radicalization becomes apparent only in their combination. Considering pertinent combinations of behavioral indicators may thus support identification of at-risk individuals at a stage when radicalization is still at a lower level. Taken alone, single online activity may provide such a weak signal to authorities that it barely leaves a trace on their monitoring mechanisms, but amplifying this signal to make it stronger by grouping it together with other combinations of behavioral and contextual factors can provide a more comprehensive picture from which authorities can inform their assessments of potential risk, threat, and harm to society.

Intensity of one or more behaviors

In addition to the types of behaviors, their intensity can provide important indications for the degree of radicalization. Intensity here refers to how often or how rapidly a certain behavior occurs. As a simple example, observing a person posting daily blog or forum discussion entries may indicate a higher level of radicalization than a person posting only once a month. While single indicators or indicator combinations consider the qualitative aspects of radicalization, intensity thus takes into account the quantitative aspects of behaviors.

Application of the framework

For investigators and analysts the proposed framework has multiple applications to support the prevention of terrorism and the pursuit of terrorists. The primary operational challenge for conducting complex investigations and analysis of online radicalization is setting a tight and focused strategy.

Our approach provides a framework and parameters within which an online investigation can be methodically progressed, tracked and monitored. The framework and model ensures a holistic approach as practitioners give due consideration to the four inter-linked factors, including the characteristics of the radicalized individual, the environment, the radical groups and ideologies and the technologies related to online radicalization. Working within this framework, counter-terrorism practitioners can identify weak signals, early indicators and emerging behaviors of individuals on the path towards radicalization. Such early signals of online activity can be assessed and appropriately prioritized by existing intelligence and law enforcement agency tasking and coordination mechanisms. Appropriate action can then be taken where considered necessary, leading to early preventative interventions, continued monitoring or executive action.

For the adequate representation of causal mechanisms the linkage between the radicalization-factor model and behavioral indicators is crucial. Starting with a precise definition (operationalization) of online radicalization the framework asks for the informed selection of influencing factors that are known to impact the chosen operationalization of radicalization. In this way the framework enforces a clear and concise representation of causal pathways reducing the temptation to include ‘all-and-every possible variable just in case’. The consistent approach to tackle online radicalization investigation through the application of the proposed framework serves to shed light on causal variables. This provides valuable information for further analysis to identify emergent behaviors, trends and patterns of those being recruited and radicalized online. From this data, new evidenced-based policies and strategies can emerge to push the current investigation of online radicalization beyond the current state of the art.

The practical value of RFM lays also in highlighting gaps in our collective knowledge and understanding of online radicalization. It can provide evidence of behavioral and environmental factors which may inform best practice guidance for online radicalization instigative techniques and support the development of a new doctrine for contemporary counter-terrorism practice. Identification of gaps also opens new avenues for multi-disciplinary academic research, especially within the human factor, psychological and technology domains.

While the proposed model and framework in isolation makes a positive contribution to the prevention and detection of online radicalization, its greater value to the protection of the public is its full integration and adoption into existing investigative machinery. As part of the contemporary counter-terrorism tool-kit, our framework helps to ensure that all in authority are better informed today to tackle the online radicalization challenges of tomorrow.

References

1. Schmid AP. The Routledge handbook of terrorism research Oxon: Routledge; 2011.

2. Bongar B. Psychology of terrorism New York: Oxford University Press; 2007.

3. Davies L. Educating against extremism Trentham: Stoke-on-Trent; 2008.

4. Silke A. Terrorists, victims and society–Psychological perspectives on terrorism and its consequences Chichester: Wiley; 2006.

5. Sedgwick M. The concept of radicalization as a source of confusion. Terrorism and Political Violence. 2010;22:479–494.

6. McCauley C, Moskalenko S. Mechanisms of political radicalization: pathways toward terrorism. Terrorism and Political Violence. 2008;20:415–433.

7. Sageman M. Leaderless Jihad: Terror networks in the twenty-first century Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press; 2008.

8. Wiktorowicz Q. Radical Islam rising: Muslim extremism in the West Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield; 2005.

9. Hudson RA. The Sociology and psychology of terrorism: Who becomes a terrorist and why? Library of Congress, Federal Research Division. [Internet]. Retrieved from: <http://www.loc.gov/rr/frd/pdffiles/Soc_Psych_0 f_Terrorism.pdf>; 1999.

10. Awan I, Blakemore B. Policing cyber hate, cyber threats and cyber terrorism Surrey: Ashgate; 2012.

11. Wojcieszak ME. Computer-mediated false consensus: radical online groups, social networks and news media. Mass Commun Soc. 2011;14:527–546.

12. Moskalenko S, McCauley C. Measuring political mobilization: the distinction between activism and radicalism. Terrorism and Political Violence. 2009;21:239–260.