At this point we have thoroughly discussed the 12 processes of systems management and how to develop the procedures that comprise and support them in a robust manner. Now we will look more closely at the various relationships between these 12 processes to learn which ones integrate with which in the best manner. Understanding to what degree a process is tactical or strategic in nature helps us understand the integrating relationships between them.

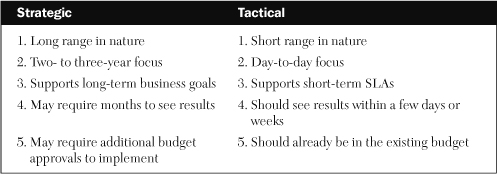

Most IT professionals seem capable of distinguishing between strategic and tactical activities. But it has been my experience that infrastructure personnel cannot always apply these differences to system management processes. Table 21-1 lists some of the key differences between strategic and tactical processes of systems management.

It is important to understand which systems management processes are strategic and which are tactical because each process integrates with, and depends on, other processes for optimal use. For example, production acceptance, change management, and problem management all interact with each other when implemented properly. Knowing which of these three key processes is tactical versus strategic helps to better understand their relationships to each other. Two processes that are both tactical will interact differently than two processes that are strategic, and each of these pairs will interact differently from a pair that is a mixture of strategic and tactical. Knowledge of a process’s orientation can also assist in selecting process owners who are more aligned with that process’s orientation. Some prospective owners may have more ability in the strategic area, while others may be better suited for tactical processes.

We have described and given formal definitions for each of the 12 systems management processes in previous chapters. Examining these definitions and combining this analysis with the properties of strategic processes given in Table 21-1 results in five of these processes being designated as strategic:

- Production acceptance

- Capacity planning

- Strategic security

- Business continuity

- Facilities management

While all of these strategic processes have tactical aspects associated with them, the significant value of each one lies more in its strategic attributes. For example, the tactical part of production acceptance, capacity planning, and disaster recovery involves the important activities of deploying production software, installing hardware upgrades, and restoring business operations, respectively. But analysts responsible for these critical events could not execute them successfully without a strategic focus involving thorough planning and preparation.

Similarly, strategic security and facilities management tactically monitor the logical and physical environments for unauthorized access or disturbance on a continual basis. But the overriding objective of ensuring the ongoing integrity and use of the logical and physical environments requires significant strategic thinking to plan, enforce, and execute the necessary policies and procedures.

We now turn our attention from strategic processes to tactical ones. Employing a method similar to what we used in the strategic area, we identify seven processes as being tactical in nature (as detailed in the following list). Just as the strategic processes contained tactical elements, some of the tactical processes contain strategic elements. For example, the network and storage management processes involve not only the installation of network and storage equipment but the planning, ordering, and scheduling of such hardware as well—activities that require months of advance preparation. But the majority of activities associated with these two processes are tactical in nature, involving real-time monitoring of network and storage resources to ensure they are available and in sufficient quantity.

- Availability

- Performance and tuning

- Change management

- Problem management

- Storage management

- Network management

- Configuration management

There are four reasons to identifying systems management processes as either strategic or tactical in nature:

- Some analysts are strategically oriented while others are tactically oriented. Understanding which processes are strategically or tactically oriented can facilitate a more suitable match when selecting a process owner for a particular discipline.

- The emphasis an infrastructure places on specific processes can indicate its orientation toward systems management processes. An infrastructure that focuses mostly on tactical processes tends to be more reactive in nature, while those focusing on strategic processes tend to be more proactive in nature.

- Managers can identify which of their 12 infrastructure processes need the most refinement by assessing them. Knowing the orientation of the processes requiring the most improvements indicates whether the necessary improvements are tactical or strategic in nature.

- Categorizing processes as either tactical or strategic assists in addressing integration issues. In a world-class infrastructure, each of the systems management processes integrate with one or more of the other processes for optimal effectiveness. Understanding which processes are tactical and which are strategic helps facilitate this integration.

In brief, they are summarized as follow:

- Facilitates the selection of process owners

- Indicates an infrastructure’s orientation

- Quantifies orientation of improvement needs

- Optimizes the integration of processes

As previously mentioned, each of the 12 systems management processes integrate with, and depend on, other processes for optimal use. In fact, we are about to see that all of them interact with at least one of the other processes. Several interact with more than half of the remaining total. Some processes have no significant interaction, or relationship, with another specific process. So how do we know which processes form what type of relationships with which others?

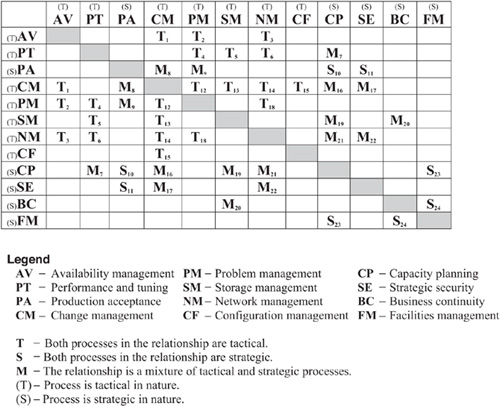

Figure 21-1 gives us these answers. Each of the 12 processes is listed across the top and down the left side of the matrix and is designated as either tactical or strategic. If the combination of two tactical processes results in a significant process relationship, then the interaction of the two is designated T for tactical. If the combination of two strategic processes results in a significant process relationship, then the interaction of the two is designated S for strategic. If a significant relationship is the result of the combination of a tactical and a strategic discipline, then the interaction is designated as M for mixture. If the combination of any two processes, either tactical or strategic, results in no significant interaction, then the intersecting box is blank.

Subscripts refer to the explanations of relationships described in the forthcoming section titled “Examining the Integrated Relationships between Strategic and Tactical Processes.”

The matrix in Figure 21-1 supplies several pieces of valuable information. It represents which processes are designated as tactical and which are strategic. It shows how each process interacts (or does not interact) with others and whether that interaction is entirely tactical, strategic, or a mixture of the two. Finally, the matrix quantifies which processes have the most interaction and which have the least. Knowledge of these interactions leads to better managed infrastructures, and managers of well-run infrastructures understand and utilize these relationships. We will examine the generic issues of integrating those processes that are solely tactical, solely strategic, and a mixture of the two.

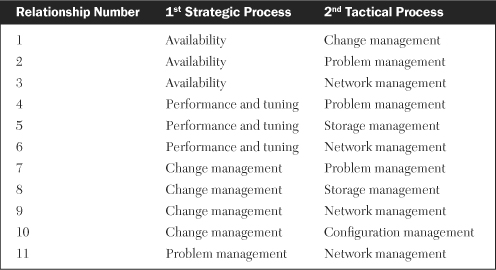

Referring to Figure 21-1, we see there are 11 relationships involving solely tactical processes. We list these 11 relationships in Table 21-2. One of the difficulties of integrating solely tactical processes is the tendency to emphasize only short-term goals and objectives. Tactical processes by their nature have very limited planning horizons, sometimes forcing an hour-to-hour focus of activities. If left unchecked, this tendency could undermine efforts at long-range, strategic planning.

Another concern with purely tactical processes is that most of these now involve 24/7 coverage. The emphasis on around-the-clock operation can often infuse an organization with a reactive, firefighting type of mentality rather than a more proactive mentality. A third issue arises out of the focus on reactive, continuous operation, and that is the threat of burnout. Shops that devote most of their systems management efforts on tactical processes run the risk of losing their most precious resource—human talent.

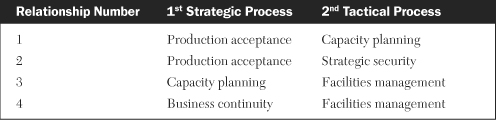

There are four relationships based solely on strategic processes and these are listed in Table 21-3. One of the difficulties with strategic relationships is that a continuing emphasis on long-range planning sometimes results in key initiatives not getting implemented. Thorough planning needs to be followed with effective execution. Another issue that more directly involves the staff is that most infrastructure analysts are more tactical than strategic in their outlooks, actions, and attitudes. These relationships must be managed by individuals with a competent, strategic focus. A final concern with strategic relationships is that budgets for strategic resources, be they software, hardware or human, often get diverted to more urgent needs.

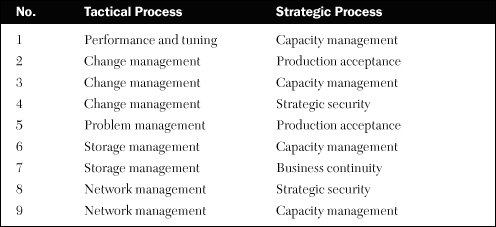

Referring again to Figure 21-1, we see there are nine relationships formed by a combination of tactical and strategic processes. These nine are listed in Table 21-4. The first, and likely most obvious, difficulty is the mixing of tactical and strategic processes, the orientations of which may appear at odds with each other. Conventional thinking would conclude that short-range tactical actions do not mix well with long-range strategic plans. But common goals of reliable, responsive systems, excellent customer service, and the accomplishment of business objectives can help to reconcile these apparent discrepancies.

Another concern with integrating these two dissimilar types of processes is that it throws together process owners whose orientation between short- and long-range focus may conflict. Again, the emphasis on common goals can help to alleviate these divergent views.

A final issue involving relationships of mixed processes is the need to recognize which elements are truly tactical and which are truly strategic. For example, the combination of tactical change management and strategic capacity management is a mixed-process relationship. But some changes may require weeks of advanced planning, resulting in a strategic focus on what is normally a tactical discipline. Similarly, the last step of a major capacity upgrade is the installation of the hardware; this is a tactical activity associated with a normally strategic discipline. Knowing and understanding these differences can help to better facilitate the relationships of mixed processes.

The previous sections discussed generic issues associated with integrating processes. Here we will look at each of the 24 relationships shown in Figure 21-1 in greater detail (in the order of the subscripts in the figure).

- AV/CM(T). Availability and change management are tactical processes. The relationship here centers mostly on scheduled outages which should be handled as scheduled changes. Unscheduled outages should be treated as problems.

- AV/PM(T). Both availability and problem management are tactical processes and involve handling outages and problems on a real-time basis. Any incident that impacts continuous availability is referred to as an outage and it is usually handled as a problem. Just as problems can be categorized as to severity, urgency, priority, and impact, outages can be categorized. A scheduled outage that results in a longer-than-planned downtime may be logged as a problem, but in all likelihood, it will be a lower priority than an unscheduled outage. Similarly, outages occurring during prime time are no doubt more severe than those occurring during the off-shifts.

- AV/NM(T). Networks now play a crucial role in ensuring online availability. Outages of entire networks are rare these days because of the use of highly reliable network components and redundant configurations. When network outages do occur, the availability of several systems is usually impacted due to the integrated nature of today’s systems.

- PT/PM(T). Performance and tuning and problem management are very closely related (often being thought of as the same issue), but there are important differences. Slow online response times, long-running jobs, excessive loading times, and ever-increasing tape backup times are performance problems since they directly affect end-user services. As such, they should be treated as problems and handled through the problem management process. But just as not all problems should be considered performance issues, not all performance issues should be considered problems. The ongoing maintenance of indices, directories, extents, page space, and swap areas; the number and size of buffers; the amount of local memory; and the allocation of cache storage are normally regarded as sound, preventative performance and tuning activities rather than problems. When done in a timely and proper manner, they should prevent problems as opposed to causing them.

- PT/SM(T). Lack of sufficient storage space, including main memory, virtual storage, cache buffering, raw physical disk storage, or logical storage groups can often result in poor online or batch performance.

- PT/NM(T). The configuration of various network devices such as routers, repeaters, hubs, and network servers can affect online performance just as various software parameters such as network retries, line speeds, and the number and size of buffers can alter transaction response times.

- PT/CP(M). This is our first relationship that mixes a tactical process (performance and tuning) with a strategic one (capacity planning). Poor performance and slow response times can certainly be attributed to lack of adequate capacity planning. If insufficient resources are available due to larger-than-expected workload growth or due to a greater number of total or concurrent users, then poor performance will no doubt result.

- PA/CM(M). This relationship is another mixture of tactical and strategic processes. New applications and major upgrades to existing applications should be brought to the attention of and discussed at a change review board. But the board should understand that for these types of implementations, a far more comprehensive production acceptance process is needed rather than just the change management process.

- PA/PM(M). This relationship between strategic production acceptance and tactical problem management occurs whenever a new application is being proposed or a major upgrade to an existing application is being planned. (For the purposes of this discussion, I will use the terms problem management and level 1 service-desk staff synonymously.)

As soon as the new system or upgrade is approved, the various infrastructure support groups, including level 1 service-desk staff, become involved. By the time deployment day arrives, the service-desk staff should have already been trained on the new application and should be able to anticipate the types of calls from users.

During the first week or two of deployment, level 2 support personnel for the application should be on the service desk to assist with call resolution, to aid in cross-training level 1 staff, and to analyze call activity. The analysis should include call volume trends and what types of calls are coming in from what types of users.

- PA/CP(S). This is the first of three systems management relationships in which both processes are strategic. New applications or major upgrades to existing applications need to go through a capacity planning process to ensure that adequate resources are in place prior to deployment.

These resources include servers, processors, memory, channels, disk storage, tape drives and cartridges, network bandwidth, and various facilitation items such as floor space, air conditioning, and conditioned and redundant electrical power. Commercial ERP systems such as SAP, Oracle, or PeopleSoft may require upgrades to the hosting operating system or database.

The capacity planning for a new application may also determine that additional resources are needed for the desktop environment. These may include increased processing power, extensions to memory, or special features such as fonts, scripts, or color capability. One of my clients implemented SAP for global use and required variations of language and currency for international use.

- PA/SE(S). This is another all-strategic relationship. New applications should have clearly defined security policies in place prior to deployment. An application security administrator should be identified and authorized to manage activities such as password expirations and resets, new-user authorization, retiring userids, and training of the help-desk staff.

- CM/PM(T). Change management and problem management are directly related to each other in the sense that some changes result in problems and some problems, in attempting resolution, result in changes. The number of changes that eventually cause problems and the number of problems that eventually cause changes are two good metrics to consider using. The collection and analysis of these metrics can be more readily facilitated by implementing the same online database tool to log and track both problems and changes.

- CM/SM(T). Changes to the type, size, or configuration of disk storage, tape libraries, main memory, or cache buffering should all go through an infrastructure’s change management process.

- CM/NM(T). Changing hubs, routers, switches, components within these devices, or the amounts or allocations of bandwidth should be coordinated through a centralized change management process. Some shops have a separate change management process just for network modifications, but this is not recommended.

- CM/CF(T). Any changes to hardware or software configurations should be administered through both the change management process (to implement the change) and the configuration management process (to document and maintain the change). The types of configuration changes that apply here include application software, system software and hardware, network software and hardware, microcode, and physical and logical diagrams of network, data center, and facilities hardware.

- CM/CP(M). The strategic side of this relationship involves long-range capacity planning. Once the type, size, and implementation date of a particular resource is identified, it can then be passed over to the more tactical change management process to be scheduled, communicated, and coordinated.

- CM/SE(M). This relationship again mixes the tactical with the strategic. The strategic portion of security involves corporate security policies and enforcement. Changes such as security settings on firewalls, new policies on the use of passwords, or upgrades to virus software should all through the change management process.

- PM/NM(T). The reactive part of network management that impacts individual users is directly tied to problem management. The same set of tools, databases, and call-in numbers used by the help desk for problem management should be used for network problems.

- SM/CP(M). Capacity planning is sometimes thought of only in terms of servers, processors, or network bandwidth, but most any capacity plan needs to factor in storage in all its various forms, including main memory, cache, disk arrays, server disks, tape drives and cartridges, and even desktop and workstation storage.

- SM/BC(M). One of the key aspects of business continuity is the ability to restore valid copies of critical data from backup tapes. One of the key responsibilities of storage management is to ensure that restorable copies of critical data are available in the event of a disaster, so there is an obvious relationship between these two processes.

- NM/CP(M). Just as network management should not have a separate change management process, it also should not have a separate capacity planning process for network resources such as hubs, routers, switches, repeaters, and especially bandwidth. This relationship is often overlooked in shops where the network has grown or changed at a rate much different from that of the data center.

- NM/SE(M). The expanding connectivity of companies worldwide and the proliferation of the Internet exposes many networks to the risk of unauthorized access to corporate assets, as well as to the intentional or inadvertent altering of corporate data. Managing network security creates a natural relationship between these two processes.

- CP/FM(S). An element of capacity planning sometimes overlooked is the effect that upgraded equipment has on the physical facilities of a data center. More than once a new piece of equipment has arrived in a computer room only to find there were no circuits or plugs or outlets with the proper adapters on which to connect it. Robust capacity planning processes will always include facilities management as part of its requirements.

- BC/FM(S). This is the final all-strategic relationship. Statistics indicate that most IT disasters are confined or localized to a small portion of the data center. As a result, proper facilities management can often prevent potential disasters. A comprehensive business continuity plan that includes periodic testing and dry runs can often uncover shortcomings in facilities management that can be corrected to prevent potential future disasters.

As previously mentioned, Figure 21-1 displays a wealth of information about the relationships of systems management processes. One final subject worth discussing is those processes that have the greatest number of relationships with others, as well as the significance of such information.

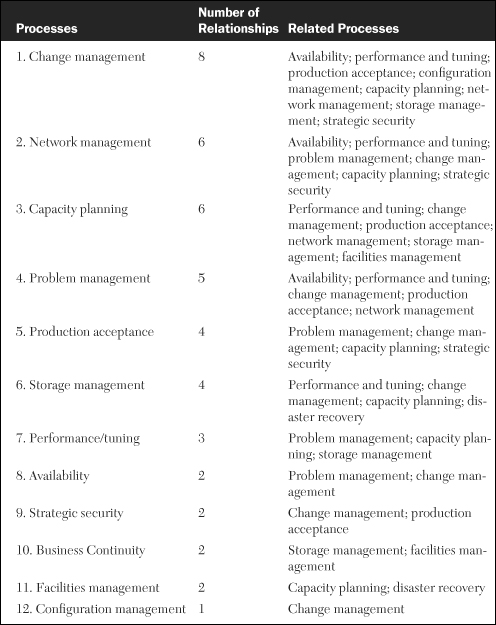

Table 21-5 is a sorted list of the number of relationships associated with each discipline. This list also represents the relative importance of individual system management functions. We see that change management has the highest number with eight. This should not be surprising. In today’s complex infrastructure environments, the quality and robustness of change management has a direct effect on the stability and responsiveness of IT services offered.

This tells us that one of the first places to look to improve an IT infrastructure is its change management function. Developing it into a more robust process will also likely improve several of the other processes with which it frequently interacts. Speaking of the frequency of interactions, I have not included the relationships of change management to performance and tuning, disaster recovery, or facilities management due to the low frequency of major changes that occur in these areas.

Problem management is next on the list with five relationships to other processes. This should come as no surprise because we have often mentioned the close relationship between problem management and change management. In fact, each of the five processes that relate to problem management also relates to change management. What may be a bit surprising is that capacity planning is also listed as having five relationships. Many shops underestimate the importance of sound capacity planning and do not realize that doing it properly requires interaction with these other five processes.

Next is production acceptance, with four relationships to other processes. Following this is the trio of performance and tuning, network management, and storage management, each of which has three relationships to other processes. Availability and security are next with two relationships each, followed by configuration management, disaster recovery, and facilities management with one relationship each.

The significance of these relationships is that they point out the relative degree of integration required to properly implement these processes. Shops that implement a highly integrated process like change management in a very segregated manner usually fail in their attempt to have a robust change process. While each process is important in its own right, the list in Table 21-5 is a good guideline as to which processes we should look at first in assessing the overall quality of an infrastructure.

World-class infrastructures not only employ the 12 processes of systems management, they integrate them appropriately for optimal use. A variety of integration issues arise that are characterized, in part, by whether the processes are strategic or tactical in nature. This chapter began by presenting the differences between strategic and tactical processes of systems management and then identifying which of the 12 fell into each category. We next discussed issues that occur when integrating strategic, tactical, or a mixture of processes.

The key contribution of this chapter was the development of a matrix that shows the 24 key relationships between the 12 processes. The matrix designated each relationship as either strategic, tactical, or a mixture, and each was then discussed in greater detail. Finally, we looked at which processes interact the most with others and discussed the significance of this.

1. Two processes that are both tactical will interact the same way as two processes that are both strategic. (True or False)

2. One of the difficulties with strategic relationships is that a continuing emphasis on long-range planning sometimes results in key initiatives not getting implemented. (True or False)

3. The infrastructure process with the largest number of relationships to other processes is:

a. problem management

b. network management

c. capacity planning

d. change management

4. Categorizing processes as either tactical or strategic assists in addressing ____________ issues.

5. Discuss some of the reasons it is important to understand which systems management processes are strategic and which are tactical.