This chapter will present the decisions an infrastructure organization must make to manage IT networks, a nontrivial challenge in light of the diversity of current IT environments. Today’s networks come in a variety of sizes, scopes, and architectures, from a simple dual-node local network in your house to a sophisticated, encrypted network connecting tens of thousands of nodes worldwide.

There obviously is no single, detailed network management process that applies to all of the various network environments, but there are common elements of the process that apply to almost all network scenarios, and the decisions that shape this process is what we will concentrate on in this chapter. We begin, as usual, with a definition of network management followed by the prioritized traits of the process owner. We next discuss six key decisions that must be made correctly in order to manage a robust network environment. These decisions apply to all network environments, regardless of platforms, protocols, or peripherals. We conclude with the standard assessment sheets customized for the network management process.

We see that our definition includes elements of two other processes:

• Availability

• Performance and tuning

Maximizing reliability is another way of emphasizing high availability by ensuring network lines and the various components such as routers, switches, and hubs maintain high levels of uptime. Maximizing utilization implies that performance and tuning activities involving these components are optimizing network response.

While availability and performance and tuning are the two processes most closely related to, and affected by, this process, network management actually interacts with six other systems management processes, making it one of the most interrelated of all 12 disciplines. The relationships of each process to all of the others are covered at length in Chapter 21, “Integrating Systems Management Processes.”

Before an effective, high-level network management process can be designed, much less implemented, six key decisions need to be made that influence the strategy, direction, and cost of the process. The following questions must be answered. These decisions define the scope of responsibilities and, more important, the functional areas that are charged with employing the process on a daily basis.

- What will be managed by this process?

- Who will manage it?

- How much authority will this person be given?

- What types of tools and support will be provided?

- To what extent will other processes be integrated with this process?

- What levels of service and quality will be expected?

This may seem like an obvious question with an obvious answer: we will manage the network. But what exactly does this mean? One of the problems infrastructures experience in this regard is being too vague as to who is responsible for which aspects of the network. This is especially true in large, complex environments where worldwide networks may vary in terms of topology, platform, protocols, security, and suppliers.

For example, some infrastructures may be responsible for both classified and unclassified networks with widely varying security requirements, supplier involvement, and government regulations. This was the case when I managed the network department at a nationwide defense contractor. We decided early on exactly which elements of network management would be managed by our department and which ones would be managed by others. For instance, we all mutually decided that government agencies would manage encryption, the in-house security department would manage network security, and computer operations along with its help desk would administer network passwords.

Was this the only arrangement we could have decided on? Obviously, it was not. Was it the best solution for anyone in a similar situation? That would depend on the situation, since each environment varies as to priorities, directions, costs, and schedule. It was the best solution for our environment at the time. Did we ever need to modify it? Certainly we did. Major defense programs rarely remain static as to importance, popularity, or funding. As external forces exerted their influences on the program, we made appropriate changes to what was included in our network management process. The key point here is to reach consensus as early as possible and to communicate with all appropriate parties as to what will be managed by this process.

Emerging and converging technologies such as wireless connectivity and voice over the Internet protocol (VoIP) are becoming more commonplace. Decisions about which of these network technologies will be included in the overall network management process need to be agreed upon and bought into by all appropriate stakeholders.

Once we decide on what we will manage, we need to decide on who will manage it. Initially, this decision should determine which department within the infrastructure will be assigned the responsibility for heading up the design, implementation, and ongoing management of this process. Within that department, a person will be assigned to have overall responsibility for the network-management process.

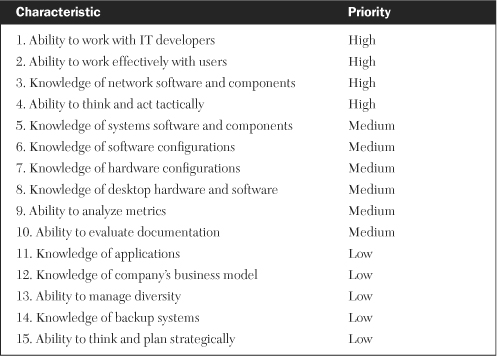

The ideal candidate to serve as network management process owner should have strong people skills, knowledge of network resources, and a sense of urgency. Table 13-1 offers a more comprehensive list, in priority order, of the traits desired in such an individual. The people skills involve working with developers on application profiles, the mix and arrival pattern of transactions, and planned increases in workloads, as well as working effectively with users on desktop requirements, connectivity, and security.

A network-management process owner should be knowledgeable about network operating systems, utility programs, support software, and key hardware components such as routers, switchers, hubs, and repeaters. One of the most valuable traits for the owner of this process is a sense of urgency in tactically responding to, and resolving, a variety of network problems. Other desirable traits include knowledge of infrastructure software and hardware and the ability to analyze metrics.

This is probably the most significant question of all because, without adequate authority, the necessary enforcement and resulting effectiveness of the process rapidly diminishes. Few practices accelerate failure more quickly than giving an individual responsibility for an activity without also providing that person with the appropriate authority. Executive support plays a key role here from several perspectives. First, managers must be willing to surrender some of their authority over the network to the individual now responsible for overseeing its management. Second, managers must be willing to support their process owner in situations of conflict that will surely arise. Conflicts involving network management can originate from several sources.

One source of conflict can come from enforcing network security policies such as if, when, and how data over the network will be encrypted or under what instances a single sign-on scheme will be employed for network and application logons. Another common source of network conflict involves user expectations about the infrastructure backing up desktop data instead of the more practical method of saving it to the server. The degree of authority a network management process owner has over network suppliers can also instigate conflict, particularly if managers have not communicated clearly to supplier management about the delegation of authority that is in effect.

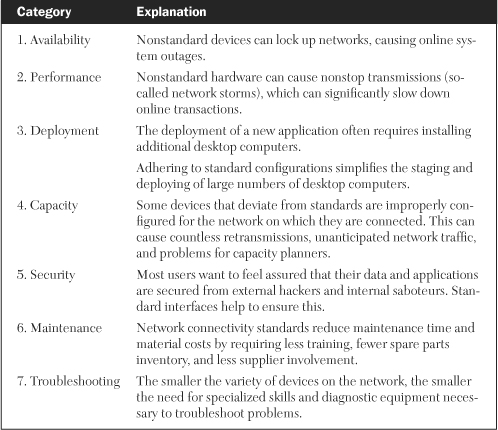

The enforcement of network connectivity standards is one of the greatest sources of conflict for network administrators. This is because most users feel that they have adequate justification to warrant an exception, and very few administrators effectively convey the legitimate business reasons for having a connectivity standard. More than once I have heard IT users in highly creative industries such as motion picture and television production companies present their arguments. Their claim is usually that their specialized artistic requirements should allow them to connect suspect devices with unproven interfaces to the network, even though alternate devices with standard interfaces could be used.

On the other hand, I have had opportunity of working with network administrators and process owners who both helped or hurt their cause of enforcing network connectivity standards. The group that undermined their own efforts at enforcement failed for two reasons:

- They failed to offer compelling arguments to users as to why it was in their own best interest to comply with connectivity standards.

- The network group did not have adequate tools in place to enforce compliance with the standards.

The group who helped their cause of enforcing network connectivity standards did so by presenting several persuasive reasons why adhering to these standards would benefit users and suppliers alike. Table 13-2 lists the seven categories, with explanations, into which these reasons fall.

There is a third perspective concerning an executive who delegates security enforcement authority to a network administrator. This involves the executive’s reaction to mistakes the administrator may make. Factors such as experience, training, fatigue, judgment, negligence, oversight, attitude, and abuse should all be considered in determining the appropriate response to a potential misuse of authority.

Decisions about the type of tools and the amount of vendor support that will be provided directly influence the costs of managing networks. In general, the costs of these two entities are inversely proportional. As more money is spent on vendor support, the need for expensive, sophisticated diagnostic tools should lessen. As more advanced tools are acquired and effectively used by in-house personnel, the need for costly, premium vendor support should correspondingly go down. One exception is classified networks where the granting of security clearances may reduce the number of vendor personnel cleared to a program. In this instance, the costs of vendor overtime and the expenses for sophisticated tools to troubleshoot encrypted lines could both increase.

A variety of network tools are available to monitor and manage a network. Some are incorporated in hardware components, but most are software-based. Costs can range from just a few thousand dollars to literally millions of dollars for multi-year contracts with full onsite maintenance. The expense for tools can sometimes be mitigated by leveraging what other sites may be using, by negotiating aggressive terms with reluctant suppliers, and by inventorying your in-house tools. Several of my clients have discovered they were paying for software licenses for products they were unaware they owned.

One tool often overlooked for network management is one that will facilitate network documentation. The criticality and complexity of today’s networks require clear, concise, and accurate documentation for support, repair, and maintenance. Effective network management requires documentation that is both simple to understand yet thorough enough to be meaningful. Useful pieces of this type of documentation is seldom produced because of a lack of emphasis on this important aspect of network management. Couple this with senior network designers’ general reluctance to document their diagrams in a manner meaningful to less experienced designers and the challenge of providing this information becomes clear.

There are a number of standard network-diagramming tools available to assist in generating this documentation. The major obstacle is more often the lack of accountability than it is the lack of tools. The executive sponsor and the process both need to enforce documentation policy as it pertains to network management. One of the best tools I have seen offered to network designers is the use of a skilled technical writer who can assist designers over the hurdles of network documentation.

A well-designed network management process will have strong relationships to six other systems management processes (we will discuss this further in Chapter 21). These processes are availability, performance and tuning, change management, problem management, capacity planning, and security. The extent to which network management integrates with these other processes by sharing tools, databases, procedures, or cross-trained personnel will influence the effectiveness of the process.

For example, capacity planning and network management could both share a tool that simulates network workloads to make resource forecasts more accurate. Similarly, a tool that controls network access may have database access controls that the security process could use.

The levels of service and quality that network groups negotiate with their customers directly affect the cost of hardware, software, training, and support. This is a key decision that should be thoroughly understood and committed to by the groups responsible for budgeting its costs and delivering on its agreements.

Suppliers of network components (such as routers, switches, hubs, and repeaters) should also be part of these negotiations since their equipment has a direct impact on availability and performance. Long-distance carriers are another group to include in the development of SLAs. Many carriers will not stipulate a guaranteed percentage of uptime in their service contracts because of situations beyond their control, such as natural disasters or manmade accidents (for example, construction mishaps). In these instances, companies can specify certain conditions in the service contract for which carriers will assume responsibility, including spare parts, time to repair, and on-call response times.

SLAs for the network should be revisited whenever major upgrades to hardware or bandwidth are put in place. The SLAs should also be adjusted whenever significant workloads are added to the network to account for increased line traffic, contention on resources, or extended hours of service.

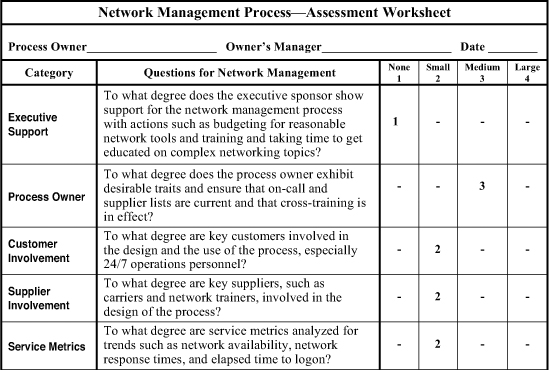

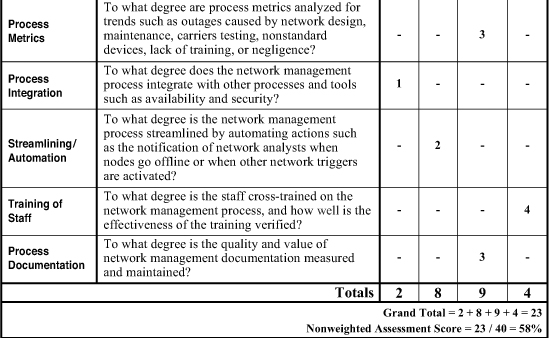

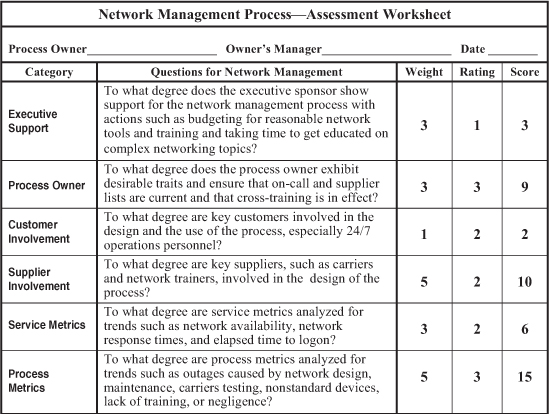

The worksheets shown in Figures 13-1 and 13-2 present a quick and simple method for assessing the overall quality, efficiency, and effectiveness of a network management process. The first worksheet is used without weighting factors, meaning all 10 categories are weighted evenly for the assessment of a network-management process. Sample ratings are inserted to illustrate the use of the worksheet. In this case, the-network management process scored a total of 23 points for an overall nonweighted assessment score of 58 percent, as compared to the second sample worksheet, which compiled a weighted assessment score of 61 percent.

One of the most valuable characteristics of these worksheets is that they are customized to evaluate each of the 12 processes individually. The worksheets in this chapter apply only to the network management process. However, the fundamental concepts applied in using these evaluation worksheets are the same for all 12 disciplines. As a result, the detailed explanation on the general use of these worksheets presented near the end of Chapter 7, “Availability,” also applies to the other worksheets in the book. Please refer to that discussion if you need more information.

We can measure and streamline the network management process with the help of the assessment worksheet shown in Figure 13.1. We can measure the effectiveness of a network management process with service metrics such as network availability, network response times, and elapsed time to logon. Process metrics—such as outages caused by network design, maintenance, carriers testing, nonstandard devices, lack of training, or negligence—help us gauge the efficiency of this process. And we can streamline a network-management process by automating actions such as the notification of network analysts when nodes go offline or when other network triggers are activated.

This chapter discussed six key decisions that infrastructure management needs to make to implement a robust network management process. As you might expect with management decisions, they involve little with network technology and much with network processes. Defining the boundaries of the what, the who, and the how of network management are key ingredients for building a strong process foundation.

We offered suggestions on what to look for in a good candidate who will own the network management process and emphasized the need for management to delegate supportive authority, not just accountable responsibility. We also discussed the important task of integrating network management with other related processes and referenced a detailed treatment we will undertake of this topic in Chapter 21. As with previous chapters, we provided customized assessment worksheets for evaluating any infrastructure’s network management process.

1. Connecting nonstandard devices to a network can cause it to lock up, causing online system outages. (True or False)

2. Most tools used to monitor and manage networks are hardware-based rather than software-based. (True or False)

3. One of the greatest sources of conflict for a network administrator is the:

a. enforcement of network connectivity standards

b. evaluation of desirable characteristics for a network management process owner

c. identification of exactly what will be managed

d. determination of how much authority the network management process owner will be given

4. The definition of network management includes elements of the processes of _______ and __________ .

5. Explain why and how the use of advanced network tools reduces the need for more costly premium vendor support.