The better prepared we are for an IT infrastructure disaster, the less likely it seems to occur. This would not appear to make much sense in the case of natural disasters such as earthquakes, floods, or tornados. We have probably all met a few IT specialists who believe they can command the physical elements, but I have yet to see it demonstrated. When it comes to more localized events, such as broken water pipes, fires, or gas leaks, being fully prepared to deal with their consequences can minimize the adverse impact they can have on your computer systems.

This chapter discusses how to plan for the continuity of critical business processes during and immediately after a major disruption of service resulting from either a localized or a wide-spread disaster. We begin with a definition of business continuity, which leads us into the steps required to design and test a business continuity plan. An actual case study is used to highlight these points. We explain the important distinctions between disaster recovery, contingency planning, and business continuity. Some of the more nightmarish events that can be associated with poorly tested recovery plans are presented as well as some tips on how to make testing more effective. We conclude the chapter with worksheets for evaluating your own business continuity plan.

There are several key phrases in this definition. The continuous operation of critical business systems is another way of saying the act of staying in business, meaning that a disaster of any kind will not substantially interrupt the processes necessary for a company to maintain its services. Widespread disasters are normally major natural disasters, such as floods, earthquakes, or tornadoes—events that are sometimes legally referred to as acts of God.

It’s interesting to note that most all major telephone companies and line carriers will not enter into formal SLAs about the availability of their services because they say they cannot control either acts of God or acts of human negligence (such as backhoes digging up telephone lines). The key point of the definition is that business continuity is a methodology involving planning, preparation, testing, and continual updating.

A number of years ago, I managed the main IT infrastructure for a major motion picture studio in Beverly Hills, California. An event just prior to my hiring drastically changed the corporation’s thinking about disaster recovery, which led the company to ask me to develop a disaster recovery program of major proportions.

Two of this studio’s most critical applications were just coming online and were being run on IBM AS/400 midrange processors. One of the applications involved the scheduling of broadcast times for programs and commercials for the company’s new premier cable television channel. The other application managed the production, distribution, and accounting of domestic entertainment videos, laser discs, and interactive games. The company had recently migrated the development and production versions of these applications onto two more advanced models of the IBM AS/400—9406-level machines utilizing reduced instruction set computing (RISC) technology.

During the development of these applications, initial discussions began about developing a business continuity plan for these AS/400s and their critical applications. Shortly after the deployment of these applications, the effort was given a major jump-start from an unlikely source. A distribution transformer that powered the AS/400 computer room from outside the building short-circuited and exploded. The damage was so extensive that repairs were estimated to take up to five days. With no formal recovery plan yet in place, IT personnel, suppliers, and customers all scurried to minimize the impact of the outage.

A makeshift disaster-recovery site located 40 miles away was quickly identified and activated with the help of one of the company’s key vendors. Within 24 hours, the studio’s AS/400 operating systems, application software, and databases were all restored and operational. Most of the critical needs of the AS/400 customers were met during the six days that it eventually took to replace the failed transformer.

This incident accelerated the development of a formal business continuity plan and underscored the following three important points about recovering from a disaster:

• There are noteworthy differences between the concept of disaster recovery and that of business resumption.

• The majority of disasters are relatively small, localized incidents, such as broken water mains, fires, smoke damage, or electrical equipment failures.

• You need firm commitment from executive management to proceed with a formal business continuity plan.

Concerning the first point, there are noteworthy differences between the concept of disaster recovery and that of business resumption. Business resumption is defined here to mean that critical department processes can be performed as soon as possible after the initial outage. The full recovery from the disaster usually occurs many days after the business resumption process has been activated.

In this case, the majority of company operations impacted by the outage were restored in less than a day after the transformer exploded. It took nearly four days to replace all the damaged electrical equipment and another two days to restore operations to their normal state. Distinguishing between these two concepts helped during the planning process for the formal business continuty program—it enabled a focus on business resumption in meetings with key customers, while the focus with key suppliers could be on disaster recovery.

It is worth noting how the Information Technology Infrastructure Library (ITIL), discussed in Chapter 6, “Comparison to ITIL Processes,” distinguishes between these two concepts. ITIL version 2 and version 3 each introduced the notion of IT Service Continuity Management. This is essentially a combination of business continuity and disaster recovery. ITIL stresses that that IT technical recovery are closely aligned to an organization’s business continuity plan. ITIL refers to these resulting plans as service continuity plans.

The second important point that this event underscored was that the majority of disasters most likely to cause lengthy outages to computer centers are relatively small, localized incidents, such as broken water mains, fires, smoke damage, or electrical equipment failures. They typically are not the flash floods, powerful hurricanes, or devastating earthquakes frequently highlighted in the media.

This is not to say that we should not be prepared for these major disasters. Infrastructures that plan and test recovery strategies for smaller incidents are usually well on their way to having a program to handle any size of calamity. While major calamities do occur, they are far less likely and are often overshadowed by the more widespread effects of the disaster on the community. What usually makes a localized computer center disaster so challenging is that the rest of the company is normally operational and desperately in need of the computer center services that have been disrupted.

The third point was that this extended unplanned outage resulted in a firm commitment from executive management to proceed with a formal business continuity plan. In many ways, business continuity is like an insurance policy. You do not really need it until you really need it. This commitment became the first important step toward developing an effective business continuity process. A comprehensive program requires hardware, software, budget, and the time and efforts of knowledgeable personnel. The support of executive management is necessary to make these resources available.

The following list details the 13 steps required to develop an effective business continuity process. For the purposes of our discussion, business continuity is a process within a process in that we are including steps that involve contracting for outside services. We realize that, depending on the size and scope of a shop, not every business continuity process requires this type of service provider. We include it here in the interest in being thorough and because a sizable percentage of shops do utilize this kind of service.

- Acquire executive support.

- Select a process owner.

- Assemble a cross-functional team.

- Conduct a business impact analysis.

- Identify and prioritize requirements.

- Assess possible business continuity recovery strategies.

- Develop a request for proposal (RFP) for outside services.

- Evaluate proposals and select the best offering.

- Choose participants and clarify their roles on the recovery team.

- Document the business continuity plan.

- Plan and execute regularly scheduled tests of the plan.

- Conduct a lessons-learned postmortem after each test.

- Continually maintain, update, and improve the plan.

The acquisition of executive support, particularly in the form of an executive sponsor, is the first step necessary for developing a truly robust business continuity process. As mentioned earlier, there are many resources required to design and maintain an effective program. These all need funding approval from senior management to initiate the effort and to see it through to completion.

Another reason this support is important is that managers are typically the first to be notified when a disaster actually occurs. This sets off a chain of events involving management decisions about deploying the IT recovery team, declaring an emergency to the disaster recovery service provider, notifying facilities and physical security, and taking whatever emergency preparedness actions may be necessary. By involving management early in the design process, and by securing their emotional and financial buy-in, you increase the likelihood of management understanding and flawlessly executing its roles when a calamity does happen.

There are several other responsibilities of a business continuity executive sponsor. One is selecting a process owner. Another is acquiring support from the managers of the participants of the cross-functional team to ensure that participants are properly chosen and committed to the program. These other managers may be direct reports, peers within IT, or, in the case of facilities, outside of IT. Finally, the executive sponsor needs to demonstrate ongoing support by requesting and reviewing frequent progress reports, offering suggestions for improvement, questioning unclear elements of the plan, and resolving issues of conflict.

The process owner for business continuity is the most important individual involved with this process because of the many key roles this person plays. The process owner must assemble and lead the cross-functional team in such diverse activities as preparing the business impact analysis, identifying and prioritizing requirements, developing business continuity strategies, selecting an outside service provider, and conducting realistic tests of the process. This person should exhibit several key attributes and be selected very carefully. Potential candidates include an operations supervisor, the data center manager, or even the infrastructure manager.

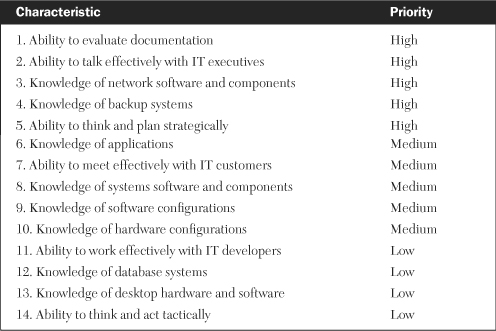

The executive sponsor needs to identify as many of these key attributes in an individual and choose the individual accordingly. Table 17-1 lists these characteristics in priority order. The finished plan needs to be well-documented and kept current, making the ability to evaluate documentation highly desirable. So, too, is the ability to talk effectively with executives, particularly when prioritizing their critical processes and applications. A strong working knowledge of network software and components is recommended because any recovery process taking place today relies heavily on the connectivity and compatibility of backup networks to those at the customer site.

Knowledge of backup systems is also very key since the restore process—with its numerous variables that can hamper recovery—is so critical to this activity. The last high-priority characteristic is the ability to think and act strategically. This means designing a process that keeps the strategic business priorities of the company in mind when deciding which processes need to be recovered first.

Representatives of appropriate departments from several areas inside and outside of IT should be assembled into a cross-functional design team. The specific departments involved vary from shop to shop, but the following list shows a representation of typical groups normally participating in a cross-functional design team. This team works on requirements, conducts a business impact analysis, selects an outside service provider, designs the final overall recovery process, identifies members of the recovery team, conducts tests of the recovery process, and documents the plan.

- Computer operations

- Applications development

- Key customer departments

- Facilities

- Data security

- Physical security

- Network operations

- Server and systems administration

- Database administration

Even the most thorough of business continuity plans will not be able to cost-justify the expense of including every business process and application in the recovery. An inventory and prioritization of critical business processes should be taken representing the entire company. Key IT customers should help coordinate this effort to ensure that all critical processes are included. Processes that must be resumed within 24 hours to prevent serious business impact, such as loss of revenue or major impact to customers, are rated as an A priority. Processes that must be resumed within 72 hours are rated as a B, and processes greater than 72 hours are rated C. These identifications and prioritizations will be used to propose business continuity strategies.

One of the first activities of the cross-functional team is to brainstorm the identity of requirements for the process, such as business, technical, and logistical requirements. Business requirements include defining the specific criteria for declaring a disaster and determining which processes are to be recovered and in what time frames. Technical requirements include what type of platforms will be eligible as recovery devices for servers, disk, and desktops and how much bandwidth will be needed. Logistical requirements include the amount of time allowed to declare a disaster as well as transportation arrangements at both the disaster site and the recovery site.

Based on the business impact analysis and the list of prioritized requirements, the cross-functional team should propose and assess several alternative business continuity recovery strategies. These will likely include alternative remote sites within the company and geographic hot sites supplied by an outside provider.

Presuming that the size and scope of the shop is sufficiently large and that the requirements involving business continuity warrant outside services, the cross-functional team develops request for proposal (RFP), which is a proposal for an outside provider to supply disaster recovery services. Options should include multiple-year pricing, guaranteed minimum amount of time to become operational, costs of testing, provisions for local networking, and types of onsite support provided. Criteria should be weighted to facilitate the evaluation process.

The weighted criteria previously established by the cross-functional team are now used by them to evaluate the responses to the RFP. Visits to the bidder’s facilities and testimonials from customers should be part of the evaluation process. The winning proposal should go to the bidder who provides the greatest overall benefit to the company, not simply to the bidder who is the lowest cost provider.

The cross-functional team chooses the individuals who will participate in the recovery activities after any declared disaster. The recovery team may be similar to the cross-functional team as suggested in Step 5, but should not be identical. Additional members should include representatives from the outside service provider, key customer representatives based on the prioritized business impact analysis, and the executive sponsor. Once the recovery team is selected, it is imperative that each individual’s role and responsibility is clearly defined, documented, and communicated.

The last official activity of the cross-functional team is to document the business continuity plan for use by the recovery team, which then has the responsibility for maintaining the accuracy, accessibility, and distribution of the plan. Documentation of the plan must also include up-to-date configuration diagrams of the hardware, software, and network components involved in the recovery.

Business continuity plans should be tested a minimum of once per year. During the test, a checklist should be maintained to record the disposition and duration of every task that was performed for later comparison to those of the planned tasks. Infrastructures with world-class disaster recovery programs test at least twice per year. When first starting out, particularly for complex environments, consider developing a test plan that spans up to three years—every six months the tests can become progressively more involved, starting with program and data restores, followed by processing loads and print tests, then initial network connectivity tests, and eventually full network and desktop load and functionality tests.

Dry-run tests are normally thoroughly planned well in advance, widely communicated, and generally given high visibility. Shops with very robust business continuity plans realize that maintaining an effective plan requires testing that is as close to simulating an actual disaster as possible. One way to do this is to conduct a full-scale test in which only two or three key people are aware that it is not an actual disaster. These types of drills often flush out minor snags and communication gaps that could prevent an otherwise flawless recovery. Thoroughly debrief the entire team afterward, making sure to explain the necessity of the secrecy.

The intent of the lessons-learned postmortem is to review exactly how the test was executed as well as to identify what went well, what needs to be improved, and what enhancements or efficiencies could be added to improve future tests.

An infrastructure environment is ever-changing. New applications, expanded databases, additional network links, and upgraded server platforms are just some of the events that render the most thorough of disaster recovery plans inaccurate, incomplete, or obsolete. A constant vigil must be maintained to keep the plan current and effective. When maintaining a business continuity plan, additional concerns to keep in mind include changes in personnel affecting training, documentation, and even budgeting for tests.

During my 25 years of managing and consulting on IT infrastructures, I have experienced directly, or indirectly through individuals with whom I have worked, a number of nightmarish incidents involving disaster recovery. Some are humorous, some are worthy of head-scratching, and some are just plain bizarre. In all cases, they totally undermined what would have been a successful recovery from either a real or simulated disaster. Fortunately, no single client or employer with whom I was associated ever experienced more than any two of these, but in their eyes, even one was too many. The following incidents illustrate how critical the planning, preparation, and performance of the disaster recovery plan really is:

- Backup tapes have no data on them.

- Restore process has never been tested and found to not work.

- Restore tapes are mislabeled.

- Restore tapes cannot be found.

- Offsite tape supplier has not been paid and cannot retrieve tapes.

- Graveyard-shift operator does not know how to contact recovery service.

- Recovery service to a classified defense program is not cleared.

- Recovery service to a classified defense program is cleared, but individual personnel are not cleared.

- Operator cannot fit tape canister onto the plane.

- Tape canisters are mislabeled.

The first four incidents all involve the handling of the backup tapes required to restore copies of data rendered inaccessible or damaged by a disaster. Verifying that the backup and—more important—the restore process is completing successfully should be one of the first requirements of any disaster recovery program. While most shops verify the backup portion of the process, more than a handful do not test that the restore process also works. Labels and locations can also cause problems when tapes are marked or stored improperly.

Although rare, I did know of a client who was denied retrieval of a tape because the offsite tape storage supplier had not been paid in months. Fortunately, it was not during a critical recovery. Communication to, documentation of, and training of all shifts on the proper recovery procedures are a necessity. Third-shift graveyard operators often receive the least of these due to their off hours and higher-than-normal turnover. These operators especially need to know who to call and how to contact offsite recovery services.

Classified environments can present their own brand of recovery nightmares. One of my classified clients had applied for a security clearance for its offsite tape storage supplier and had begun using the service prior to receiving clearance. When the client’s military customer found out, the tapes were confiscated. In a related issue, a separate defense contractor cleared its offsite vendor for a secured program but failed to clear the one individual who worked nights, which is when a tape was requested for retrieval. The unclassified worker could not retrieve the classified tape that night, delaying the retrieval of the tape and the restoration of the data for at least a day.

The last two incidents involve tape canisters used during a full dry-run test of restoring and running critical applications at a remote hot site 3,000 miles away. The airline in question had just changed its policy for carry-on baggage, preventing the canisters from staying in the presence of the recovery team. Making matters worse was the fact that they were mislabeled, causing over six hours of restore time to be lost. Participants at the lesson-learned debriefing had much to talk about during its marathon postmortem session.

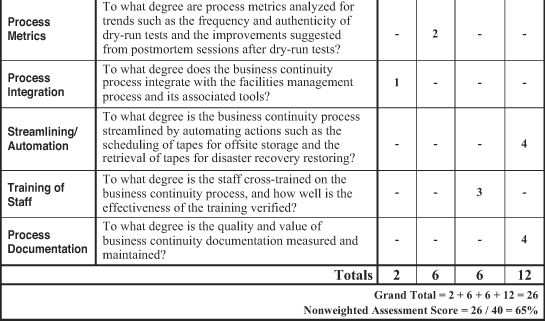

The worksheets shown in Figures 17-1 and 17-2 present a quick-and-simple method for assessing the overall quality, efficiency, and effectiveness of a business continuity process. The first worksheet is used without weighting factors, meaning that all 10 categories are weighted evenly for the assessment of a disaster recovery process. Sample ratings are inserted to illustrate the use of the worksheet. In this case, the disaster recovery process scored a total of 26 points for an overall nonweighted assessment score of 65 percent. The second sample worksheet compiled a nearly identical weighted assessment score of 66 percent.

One of the most valuable characteristics of these worksheets is that they are customized to evaluate each of the 12 processes individually. The worksheets in this chapter apply only to the business continuity process. However, the fundamental concepts applied in using these evaluation worksheets are the same for all 12 disciplines. As a result, the detailed explanation on the general use of these worksheets presented near the end of Chapter 7, “Availability,” also applies to the other worksheets in the book. Please refer to that discussion if you need more information.

We can measure and streamline a business continuity process with the help of the assessment worksheet shown in Figure 17-1. We can measure the effectiveness of a business continuity process with service metrics such as the number of critical applications that can be run at backup sites and the number of users that can be accommodated at the backup site. Process metrics—such as the frequency and authenticity of dry-run tests and the improvements suggested from postmortem sessions after dry-run tests—help us gauge the efficiency of this process. And we can streamline the disaster recovery process by automating actions such as the scheduling of tapes for offsite storage and the retrieval of tapes for disaster recovery restorations.

We began this chapter with the definition of disaster recovery and then we discussed a case study of an actual disaster, the aftermath of which I was directly involved. This led to the explanation of the 13 steps used to develop a robust disaster recovery program. Some of the more salient steps include requirements, a business impact analysis, and the selection of the appropriate outside recovery services provider. Over the years I have experienced or been aware of numerous nightmare incidents involving disaster recovery and I presented many of those. The final section offers customized assessment sheets used to evaluate an infrastructure’s disaster recovery process.

1. The terms disaster recovery, contingency planning, and business continuity all have the same meaning. (True or False)

2. Business continuity plans should be tested a minimum of once every two years. (True or False)

3. A business impact analysis results in a prioritization of:

a. critical business processes

b. vital corporate assets

c. important departmental databases

d. essential application systems

4. Several business continuity __________ __________ should be proposed based on the results of the business impact analysis.

5. Describe why a firm commitment from executive management is so important in the development of a formal business continuity program.