Change management is one of the most critical of systems management processes. In Chapter 21, “Integrating Systems Management Processes,” Table 21-2 lists the 12 processes in order of the most interaction with other disciplines. The process of change management easily tops the chart as having the most interactions with other disciplines.

We begin with the definition of change management and point out the subtle but important difference between change control and change coordination. We next present some of the common drawbacks of most change management processes taken from recent surveys of leading infrastructure managers.

The heart of the chapter comes next as we identify the 13 steps required to design and implement an effective change management process. We describe each step in detail and include figures, charts, and tables where appropriate to illustrate salient points. The chapter concludes with an example of how to assess a change management environment.

Later in this chapter, we define a whole set of terms associated with change management. Let me say at the outset that a change is defined as any modification that could impact the stability or responsiveness of an IT production environment. Some shops interchange the terms change management and change control, but there is an important distinction between the two expressions. Change management is the overall umbrella under which control and change coordination reside. Unfortunately, to many people, the term change control has a negative connotation. Let’s talk about it further.

To many IT technicians, change control implies restricting, delaying, or preventing change. But to system, network, and database administrators, change is an essential part of their daily work. They view any impediments to change as something that will hinder them as they try to accomplish their everyday tasks. Their focus is on implementing a large number of widely varying changes as quickly and as simply as possible. Since many of these are routine, low-impact changes, technicians see rigid approval cycles as unnecessary, non-value-added steps. This is a challenge to infrastructure managers initiating a formal change management process. They need the buy-in of the individuals who will be most impacted by the process and are the most suspect of it.

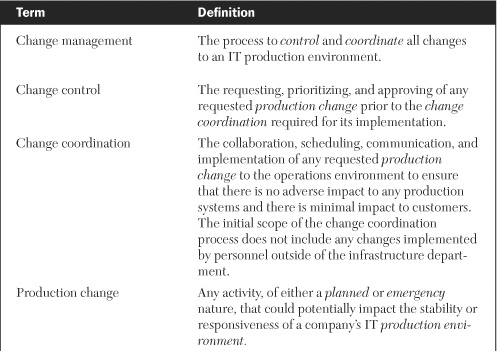

One way to address this dilemma is to break change management into two components—change control and change coordination—and to focus on the latter at the outset. As the process becomes more refined, the emphasis should expand to include more formal requesting, prioritizing, and approvals. Table 10-1 illustrates the scope and components of change management schematically.

The following list describes each component.

• Request. Submit to a reviewing board a hard copy or electronic request for a change to be made. For example, suppose tax tables need to be changed for the new year in a payroll application. The software maintenance programmer for this application would submit the change request to the change advisory board.

• Prioritize. Specify the priority of the change request based on criteria that have been agreed upon. In the previous tax/payroll change example, the change would likely be given a high priority.

• Approve. Recommend by a duly authorized review board that the change request be scheduled for implementation or that it be deferred for pending action. In the tax/payroll example, the change would likely be approved by the change advisory board pending successful testing of the change.

• Collaborate. Facilitate effective interaction between appropriate members of support groups to ensure successful implementation; log and track the change. For the tax/payroll example, this may include database administrators who maintain specific tables and end-users who participate in user-acceptance testing.

• Schedule. Agree upon the date and time of the change, which systems and customers will be impacted and to what degree, and who will implement the change. In the previous example, the change would need to occur at the time the new tax tables would go into effect.

• Communicate. Inform all appropriate individuals about the change via agreed-upon means. For the tax/payroll example, the communication would go out to all users, service-desk personnel (in the event users call in about the change), and support analysts.

• Implement. Enact the change; log final disposition; and collect and analyze metrics. In the previous example, the change would go in and be verified jointly by the implementers and the payroll users.

Change management is one of the oldest and most important of the 13 systems management disciplines. You might think that, with so many years to refine this process and grow aware of its importance, change management would be widely used, well designed, properly implemented, effectively executed, and have little room for improvement. Surprisingly, in the eyes of many executives, the opposite is true.

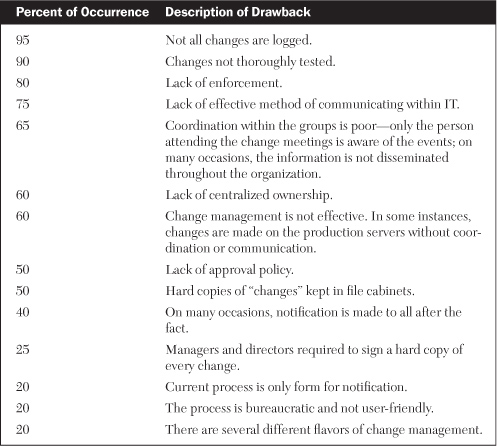

In a recent survey, more than 40 leading infrastructure managers were asked to identify major drawbacks with their current change management processes. Table 10-2 lists the 14 drawbacks they offered, in their own words, and the percentage of managers responding to each one shown as a percent of occurrences. One of the reasons for so many opportunities for improvement is this—it is much easier and more common for shops to implement only parts of change management in a less-than-robust manner than it is to formally institute all the elements of the process.

There are 13 steps required to implement an effective change management process. Each step will be discussed in detail and augmented where appropriate with examples and forms:

- Identify an executive sponsor.

- Assign a process owner.

- Select a cross-functional process design team.

- Arrange for meetings of the cross-functional process design team.

- Establish roles and responsibilities for members supporting the design team.

- Identify the benefits of a change management process.

- If change metrics exist, collect and analyze them; if not, set up a process to do so.

- Identify and prioritize requirements.

- Develop definitions of key terms.

- Design the initial change management process.

- Develop policy statements.

- Develop a charter for a Change Advisory Board (CAB).

- Use the CAB to continually refine and improve the change management process.

An effective change management process requires the support and compliance of every department in a company that could affect change to an IT production environment. This includes groups within the infrastructure, such as technical services, database administration, network services, and computer operations; groups outside of the infrastructure, such as the applications development departments; and even areas outside of IT, such as facilities.

An executive sponsor must garner support from, and serve as a liaison to, other departments; assign a process owner; and provide guidance, direction, and resources to the process owner. In many instances, the executive sponsor is the manager of the infrastructure, but he or she could also be the manager of the department in which change management resides or he or she could be the manager of the process owner.

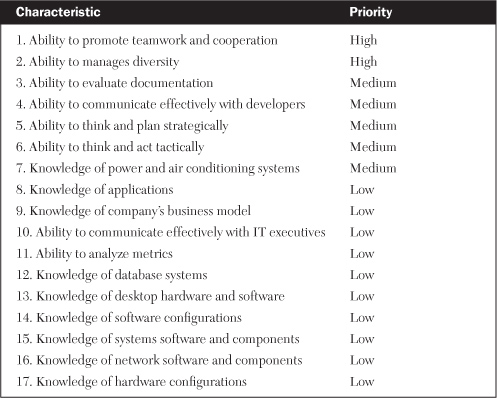

As previously mentioned, one of the responsibilities of the executive sponsor is to assign a process owner. The ideal process owner possesses a variety of skills and attributes to accomplish a variety of tasks. These tasks include assembling and leading teams, facilitating brainstorming sessions, conducting change review meetings, analyzing and distributing process metrics, and maintaining documentation.

High on the list of desirable attributes are the abilities to promote teamwork and cooperation and to effectively manage highly diverse groups. Table 10-3 shows a number of other preferred characteristics in priority order. This list should be tailored to individual shops because priority attributes likely vary from one infrastructure to another.

The success of a change management process is directly proportional to the degree of buy-in from the various groups that will be expected to comply with it. One of the best ways to ensure this buy-in is to assemble a process design team consisting of representatives from key functional areas. The process owner, with support from the executive sponsor, will select and lead this team. It will be responsible for completing several preparatory steps leading to the design of the initial change management process.

This sounds routine but actually is not. The diversity of a well-chosen team can cause scheduling conflicts, absentee members, or misrepresentation at times of critical decision making. It is best to have consensus from the entire team at the outset as to the time, place, duration, and frequency of meetings. The process owner can then make the necessary meeting arrangements to enact these agreements.

Each individual who has a key role in the support of the process design team should have clearly stated responsibilities. The process owner and the cross-functional design team should propose these roles and responsibilities and obtain concurrence from the individuals identified. Table 10-4 shows examples of what these roles and responsibilities could look like.

One of the challenges for the process owner and the cross-functional team will be to market the use of a change management process. If an infrastructure is not experienced with marketing a new initiative, this effort will likely not be a trivial task. Identifying and promoting the practical benefits of this type of process can help greatly in fostering its support. The following list offers some examples of common benefits of a change management process:

• Visibility. The number and types of all changes logged will be reviewed at each week’s CAB meeting for each department or major function. This shows the degree of change activity being performed in each unit.

• Communication. The weekly CAB meeting is attended by representatives from each major area. Communication is effectively exchanged among board members about various aspects of key changes, including scheduling and impacts.

• Analysis. Changes that are logged into the access database can be analyzed for trends, patterns, and relationships.

• Productivity. Based on the analysis of logged changes, some productivity gains may be realized by identifying root causes of repeat changes and eliminating duplicate work. The reduction of database administration change is a good example of this.

• Proactivity. Change analysis can lead to a more proactive approach toward change activity.

• Stability. All of the previous benefits can lead to an overall improvement in the stability of the production environment. Increased stability benefits customers and support staff alike.

An initial collection of metrics about the types, frequencies, and percentages of change activity can be helpful in developing process parameters such as priorities, approvals, and lead times. If no metrics are being collected, then some initial set of metrics needs to be gathered, even if it must be collected manually. One of the most meaningful of change metrics is the percentage of emergency changes to total changes. This metric is covered in more detail in the next section.

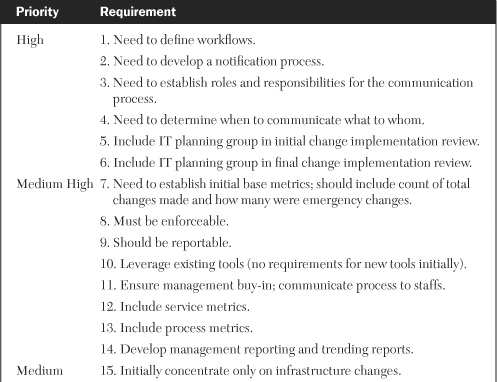

One of the key preparatory tasks of the cross-functional design team is to identify and prioritize requirements of the change management process. Prioritizing is especially important because budget, time, or resource constraints may prevent all requirements from being met initially. Techniques for effectively brainstorming and prioritizing requirements are presented in Chapter 19, “Developing Robust Processes.” Table 10-5 shows some examples of prioritized requirements from a composite of prior clients.

Change management involves several key terms that should be clearly defined by the design team at the beginning to avoid confusion and misunderstandings later on. Because there are nine terms to define, they all have been placed in Table 10-6 rather than the standard Terms and Definitions box. Planned and emergency changes are especially noteworthy.

This is one of the key activities of the cross-functional team because this is where the team proposes and develops the initial draft of the change management process. The major deliverables produced in this step are:

• A priority scheme

• A change request form

• A review methodology

• Metrics

The priority scheme should apply to both planned changes and emergency changes (these two categories should have been clearly defined in Step 9). A variety of criteria should be identified to distinguish different levels of planned changes. Typical criteria includes quantitative items such as the number of internal and external customers impacted as well as the number of hours to implement and back out the change. The criteria could also include qualitative items such as the degree of complexity and the level of risk.

Some shops employ four levels of planned changes to offer a broader variety of options. Many shops just starting out with formalized change management begin with a simpler scheme comprised of only two levels. Table 10-7 lists some quantitative and qualitative criteria for four levels of planned changes. Table 10-8 does the same for two levels.

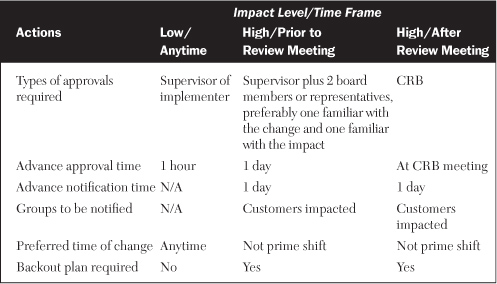

After the team determines priority levels, it must develop lists of actions to be taken depending on the level of planned or emergency change. Table 10-9 shows some sample actions for planned changes by impact level and time frame.

The following list describes sample actions for emergency changes:

- If not an emergency change, then follow the actions in the action matrix for planned changes.

- Implementer or recovery team rep notifies all appropriate parties, including the support center of the emergency change.

- Recovery team should initiate recovery action within 2 hours.

- Recovery team should determine problem status update interval for support center.

- If status interval is exceeded, recovery team rep updates support center.

- Support center to notify all appropriate parties of the update.

- Repeat steps #5 and #6 until problem is resolved.

- Support center issues final resolution to all appropriate parties.

- Implementer logs activity as an emergency change.

- CAB issues final disposition of the emergency change at the next CAB meeting.

- Change manager records the board’s final disposition of the change into the emergency change request record.

The team next develops a change request form. Two characteristics are always present in such a form: simplicity and accessibility. The form needs to be simple enough to use that minimum explanation is required, yet thorough enough that all pertinent information is provided. The form also needs to be easily accessible to users, preferably through a company’s intranet or in a public email folder on a shared drive. Change requests should be stored in a database—preferably a relational database—for subsequent tracking and analysis. Figure 10-1 shows a sample change request form.

The next task for the cross-functional team is to devise a methodology for reviewing all changes. Most shops constitute a CAB that meets weekly to review the prior week’s changes and to discuss upcoming changes. The final part of this step involves the establishment of metrics for tracking, analyzing, and trending the number and types of planned and emergency changes occurring every week.

Regardless of how well the cross-functional team designs a change management process, it will not be effective unless there is support, compliance, enforcement, and accountability. These are the objectives of policy statements. They are what give a process visibility and credibility. These statements should reflect the philosophy of executive management, the process design team, and the users at large. The following list illustrates a set of sample policy statements for change management:

- All hardware and software changes that could potentially impact the stability or the performance of company X’s IT production environment are to go through the change management process.

- The senior director of the infrastructure department is the executive sponsor of the change management process.

- Employee Y is the IT change manager. In employee Y’s absence, employee Z will serve as the IT change manager.

- The IT change manager is responsible for chairing a weekly meeting of the CAB at which upcoming major changes are discussed, approved, and scheduled; also, the prior week’s changes are reviewed and dispositioned by the board.

- The IT change manager will have sole responsibility of entering the final disposition of each change based on the recommendation of the board.

- All CAB areas serving in either a voting or advisory role are expected to send a primary or alternate representative to each weekly meeting.

- All IT staff members and designated vendors implementing production changes are expected to log every change into the current IT tracking database.

- Board members are required to discuss any unlogged changes they know about at the weekly CAB meeting. These unlogged changes will then be published in the following week’s agenda.

- All planned changes are to be categorized as either high-impact or low-impact based on the criteria established by the CAB. Implementers and their supervisors should determine the appropriate impact level of each change in which they are involved. Any unplanned change must comply with the criteria for an emergency change described in the document mentioned in this item.

- The IT change manager, in concert with all board members, is expected to identify and resolve any discrepancies in impact levels of changes.

- Approvals for all types of changes must follow the procedures developed and published by the CAB.

- The change manager is responsible for compiling and distributing a weekly report on change activity including the trending and analysis of service metrics and process metrics.

The cornerstone of any change management process is the mechanism provided for the review, approval, and scheduling of changes. In almost all instances this takes the form of a Change Advisory Board (CAB). The charter for the CAB contains the governing rules of this critical forum and specifies items such as primary membership, alternates, approving or delaying of a change, meeting logistics, enforcement, and accountability. During the initial meeting of the CAB, a number of proposals should be agreed on, including roles and responsibilities, terms and definitions, priority schemes and associated actions, policy statements, and the CAB charter itself. The following statements comprise a sample CAB charter:

- Review all upcoming high-impact change requests submitted to the CAB by the change coordinator as follows:

Approve if appropriate.

Modify on the spot (if possible) and approve (if appropriate).

Send back to requester for additional information.

Cancel at the discretion of the board.

- Review a summary of the prior week’s changes as follows:

Validate that all emergency changes from the prior week were legitimate.

Review all planned change requests from the prior week as to impact level and lead time.

Bring to the attention of the board any unlogged changes.

Bring to the attention of the board any adverse impact an implemented change may have caused and recommend a final disposition for these.

Analyze total number and types of changes from the prior week to evaluate trends, patterns, and relationships.

- CAB will meet every Wednesday from 3 p.m. to 4 p.m. in room 1375.

- CAB meeting will eventually become part of a systems management meeting at which the status of problems, service requests, and projects are also discussed.

- Changes will be approved, modified, or cancelled by a simple majority of the voting members present.

- Disputes will be escalated to the senior director of the infrastructure department.

Some time should be set aside at every meeting of the CAB to discuss possible improvements to any aspect of the change management process. Improvements voted on by the CAB should then be assigned, scheduled for implementation, and followed up at subsequent meetings.

One of the most significant metrics for change management is the number of emergency changes occurring each week, especially when compared to the weekly number of high-impact changes and total weekly changes. There is a direct relationship between the number of emergency changes required and the degree to which a shop is proactive. The higher the number of emergency changes, the more reactive the environment. Numbers vary from shop to shop, but if more than 15 to 20 percent of the total changes are classified as emergency, the shop is considered more reactive than proactive. Just as important as the raw percentages is the trending over time. As improvements to the change process are put in place, there should be a corresponding reduction in the percentage of emergency changes. A low number of emergency changes indicate a highly proactive environment where most changes are thoroughly planned and properly coordinated well in advance. Table 10-10 shows some desirable levels of percentages of emergency changes.

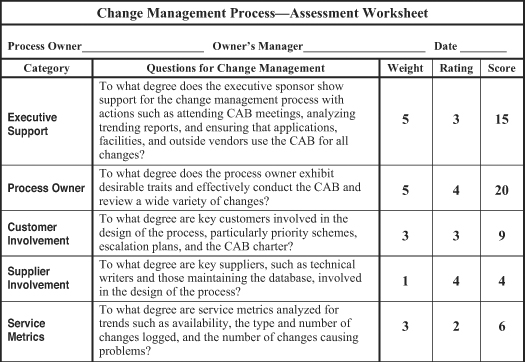

The worksheets shown in Figures 10-2 and 10-3 present a quick-and-simple method for assessing the overall quality, efficiency, and effectiveness of a change management process. The first worksheet is used without weighting factors, meaning that all 10 categories are weighted evenly for the assessment of a change management process. Sample ratings are inserted to illustrate the use of the worksheet. In this case, the change management process scored a total of 29 points for an overall nonweighted assessment score of 73 percent. Our second sample worksheet compiled an almost identical weighted assessment score of 74 percent.

One of the most valuable characteristics of these worksheets is that they are customized to evaluate each of the 12 processes individually. The worksheets in this chapter apply only to the change management process. However, the fundamental concepts applied in using these evaluation worksheets are the same for all 12 disciplines. As a result, the detailed explanation on the general use of these worksheets presented near the end of Chapter 7, “Availability,” also applies to the other worksheets in the book. Please refer to that discussion if you need more information.

We can measure and streamline the change management process with the help of the assessment worksheet shown in Figure 10-2. We can measure the effectiveness of a change management process by analyzing service metrics such as availability, the type and number of changes logged, and the number of changes causing problems. Process metrics—changes logged after the fact, changes with a wrong priority, absences at CAB meetings, and late metrics reports, for example—help us gauge the efficiency of this process. And we can streamline the change management process by automating certain actions—changes logged after the fact, changes with wrong priorities, absences at CAB meetings, and late metrics reports, just to name some.

Change management is one of the oldest and possibly the most important of the systems management processes, but it often causes infrastructure managers major process challenges. After defining the differences between change management and change control, we presented the results of an executive survey that prioritized these challenges and drawbacks.

We then discussed each of the 13 steps involved with designing and implementing a robust change management process. These steps included assembling a cross-functional team, prioritizing requirements, and establishing priority schemes, policy statements, and metrics. The cornerstone to the entire process is a Change Advisory Board (CAB), and the chartering of this forum is covered in detail. We then provided the customized assessment sheets that can be used to evaluate an infrastructure’s change management process.

1. Change management is relatively new among of the 12 systems management disciplines. (True or False)

2. In a robust change management process, the priority scheme applies only to emergency changes. (True or False)

3. Which of the following is an important aspect of a change review board’s charter?

a. validating that all planned changes from the prior week were legitimate

b. reviewing all emergency changes as to impact level and lead time

c. analyzing the total number and types of changes from the prior week to evaluate trends, patterns, and relationships

d. bringing to the attention of the board any logged changes

4. The percentage of _______________ ____________ to all changes can indicate the relative degree to which an organization is reactive or proactive.

5. Explain why you think a priority scheme for changes is, or is not, worth the overhead cost of administering and enforcing?