This chapter discusses an activity that is one of the least appealing to those installing infrastructure systems, while at the same time being one of the most necessary to those maintaining those systems. That activity is the documentation of hardware and software configurations. Technically brilliant personnel historically lack the talent or the desire, or both, to clearly document the complexities of their work in a simple, succinct manner. These analysts can often speak in volumes about the significance and application of their efforts but are reluctant to document them in any form. Ironically, their failure to document world-class technical accomplishments can lead to preventing their infrastructures from becoming world-class.

We begin, as usual, with a formal definition of configuration management and describe how it differs from application configuration management and what is called versioning control (defined in the next section). We then describe eight practical ways to improve the configuration management process, including what qualities to look for in a process owner. We conclude with assessment worksheets for evaluating the configuration management process of any infrastructure.

As it pertains to the infrastructure, configuration management refers to coordinating and documenting the different levels of hardware, firmware, and software that comprise mainframes, servers, desktops, databases, and various network devices such as routers, hubs, and switches. It does not refer to application software systems or to the verification of various levels of application software in different stages of development, testing, and deployment—these activities are commonly referred to as versioning control and are normally managed by the applications development group or by a software quality assurance group within applications development.

Infrastructure hardware such as UNIX servers come in different models requiring different levels of operating system software. As models are upgraded, the operating system may also need to be upgraded. Similarly, upgraded operating systems may require upgraded versions of database management systems software and, eventually, upgraded applications software. Keeping all these various versions of hardware and software accurately updated is the primary responsibility of the owner of the configuration management process. In addition to the hardware and software of the data center, network equipment also needs to be documented in the form of circuit diagrams, network configurations, and backbone schematics.

It is not an easy task to motivate technically oriented individuals to document configurations of what they have worked hard to implement when they would much rather be planning and working on their next implementations. These individuals must be carefully selected if they are to be involved effectively in this activity; they must also be given tools and tips to help improve and streamline the process. In support of this notion, the next section offers eight practical tips for improving configuration management.

Many of the best tips I have seen over the years to improve configuration management involve common sense about matching the documentation skill levels of technicians to the task at hand. Utilizing this knowledge, I have listed eight practical tips here for improving configuration management, each of which is followed by a brief explanation:

- Select a qualified process owner.

- Acquire the assistance of a technical writer or a documentation analyst.

- Match the backgrounds of writers to technicians.

- Evaluate the quality and value of existing configuration documentation.

- Involve appropriate hardware suppliers.

- Involve appropriate software suppliers.

- Coordinate documentation efforts in advance of major hardware and software upgrades.

- Involve the asset-management group for desktop equipment inventories.

In most instances, a single individual should be selected to own the configuration process. The desired characteristics of this process owner are listed and prioritized in Table 14-1. The process owner should have strong working knowledge of system and network software and their components as well as strong knowledge of software and hardware components. Other preferred attributes include knowledge of applications and desktop systems and the ability to think and act tactically. In some extremely large infrastructure organizations, there may be subprocess owners each for networks, systems, and databases. Even in this case there should be a higher-level manager, such as the technical services manager or even the manager of the infrastructure, to whom each subprocess owner reports.

Most shops have access to a technical writer who can generate narratives, verbiage, or procedures; or they have access to a documentation analyst who can produce diagrams, flowcharts, or schematics. Offering the services of one of these individuals, even if only for short periods of time, can reap major benefits in terms of technicians producing clear, accurate documentation in a fairly quick manner.

Another benefit of this approach is that it removes some of the stigma that many technical specialists have about documentation. Most technicians derive their satisfaction from designing, implementing, or repairing sophisticated systems and networks, not from writing about them. Having an assistant to do much of the nuts-and-bolts writing can ease both the strain and the effort technicians feel when required to do documentation.

One of the concerns raised about the use of technical writers or documentation analysts is their expense. In reality, the cost of extended recovery times that are the result of outdated documentation on critical systems and networks—particularly when localized disasters are looming—far exceeds the salary of one full-time-equivalent scribe. Documentation costs can further be reduced by contracting out for these services on a part-time basis, by sharing the resource with other divisions, and by using documentation tools to limit labor expense. Such tools include online configurators and network diagram generators.

This suggestion builds on the prior improvement recommendation of having a technical writer or documentation analyst work directly with the originator of the system being written about. Infrastructure documentation comes in a variety of flavors but generally falls into five broad configuration categories:

• Servers

• Disk volumes

• Databases

• Networks

• Desktops

There are obvious subcategories such as networks breaking out into LANs, wide-area networks (WANs), backbones, and voice.

The point here is that the more you can match the background of the technical writer to the specifications of the documentation, the better the finished product. This will also produce a better fit between the technician providing the requirements and the technical writer who is meeting them.

Evaluating existing documentation can reveal a great deal about the quality and value of prior efforts at recording current configurations. Identifying which pieces of documentation are most valuable to an organization, and then rating the relative quality of the content, is an excellent method to quickly determine which areas need improvements the most.

In Chapter 20, “Using Technology to Automate and Evaluate Robust Processes,” we present a straightforward technique to conduct such an evaluation. It has proven to be very helpful at several companies, especially those struggling to assess their current levels of documentation.

Different models of server hardware may support only limited versions of operating system software. Similarly, different sizes of disk arrays will support differing quantities and types of channels, cache, disk volumes, and densities. The same is true for tape drive equipment. Network components (such as routers and switches) and desktop computers all come with a variety of features, interconnections, and enhancements.

Hardware suppliers, while often the most qualified, are least involved in assisting with a client’s documentation. This is not to say the supplier will generate free detailed diagrams about all aspects of a layout, although I have experienced server and disk suppliers who did just that. But most suppliers will be glad to help keep documentation about their equipment current and understandable. It is very much in their best interest to do so, both from a serviceability standpoint and from a marketing one. Sometimes all it takes is asking.

Similar to their hardware counterparts, infrastructure software suppliers can be an excellent source of assistance in documenting which levels of software are running on which models of hardware. In the case of servers and operating systems, the hardware and software suppliers are almost always the same. This reduces the number of suppliers with whom you may need to work, but not necessarily the complexity of the configurations.

For example, one of my clients had hundreds of servers almost evenly divided among the operating systems HP/UNIX, Sun/Solaris, and Microsoft/NT with three or four variations of versions, releases, and patch levels associated with each supplier. Changes to the software levels were made almost weekly to one or more servers, requiring almost continual updates to the software and hardware configurations. Assistance from the suppliers as to anticipated release levels and the use of an online tool greatly simplified the process.

Software for database management, performance monitoring, and data backups also comes in a variety of levels and for specific platforms. Suppliers can be helpful in setting up initial configurations such for complex disk to tape backup schemes and may also offer online tools to assist in the upkeep of the documentation.

The upgrading of major hardware components such as multiple servers or large disk arrays can render volumes of configuration documentation obsolete. The introduction of a huge corporate database or an enterprise-wide data warehouse could significantly alter documentation about disk configurations, software levels, and backup servers. Coordinating in advance and simultaneously the many different documentation updates with the appropriate individuals can save time, reduce errors, and improve cooperation among disparate groups.

One of the most challenging of configuration management tasks involves the number, types, and features of desktop equipment. As mentioned previously, we do not include asset management in these discussions of infrastructure processes because many shops turn this function over to a procurement or purchasing department.

Regardless of where asset management is located in the reporting hierarchy, it can serve as a tremendous resource for keeping track of the myriad paperwork tasks associated with desktops, including the names, departments, and location of users; desktop features; software licenses and copies; hardware and software maintenance agreements; and network addresses. Providing asset managers with an online asset management system can make them even more productive both to themselves and to the infrastructure. The configuration management process owner still needs to coordinate all these activities and updates, but he or she can utilize asset management to simplify an otherwise enormously tedious task.

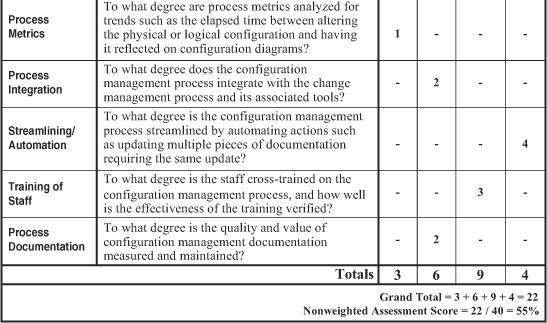

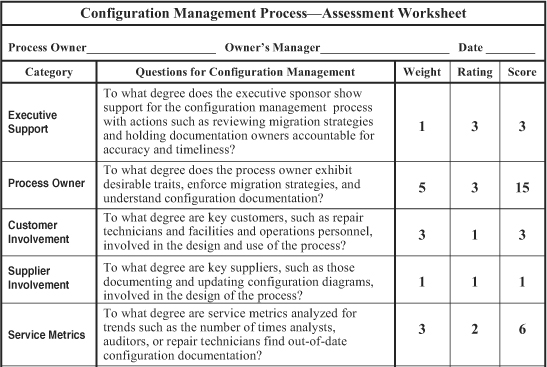

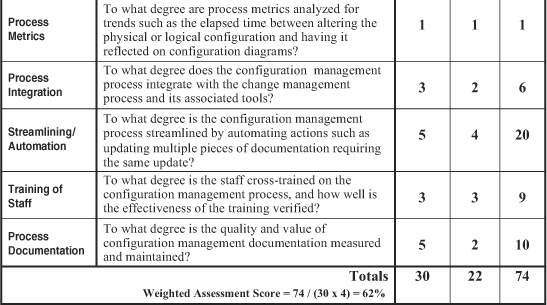

The worksheets shown in Figures 14-1 and 14-2 present a quick and simple method for assessing the overall quality, efficiency, and effectiveness of a configuration management process. The first worksheet is used without weighting factors, meaning that all 10 categories are weighted evenly for the assessment of a configuration management process. Sample ratings are inserted to illustrate the use of the worksheet. In this case, the configuration management process scored a total of 22 points for an overall nonweighted assessment score of 55 percent, as compared to the second sample worksheet, which compiled a weighted assessment score of 62 percent.

Figure 14-2. Sample Assessment Worksheet for Configuration Management Process with Weighting Factors

One of the most valuable characteristics of these worksheets is that they are customized to evaluate each of the 12 processes individually. The worksheets in the figures apply only to the configuration management process. However, the fundamental concepts applied in using these evaluation worksheets are the same for all 12 disciplines. As a result, the detailed explanation on the general use of these worksheets presented near the end of Chapter 7, “Availability,” also applies to the other worksheets in the book. Please refer to that discussion if you need more information.

We can measure and streamline the configuration management process with the help of the assessment worksheet shown in Figure 14-1. We can measure the effectiveness of a configuration management process with service metrics such as the number of times analysts, auditors, or repair technicians find out-of-date configuration documentation. Process metrics, such as the elapsed time between altering the physical or logical configuration and noting it on configuration diagrams, help us gauge the efficiency of this process. And we can streamline the configuration management process by automating certain actions—the updating of multiple pieces of documentation requiring the same update, for example.

This chapter discussed what configuration management is, how it relates to the infrastructure, and how if differs from the notion of versioning control more commonly found in applications development. We began with a formal definition of this process to help highlight these aspects of configuration management. We then offered eight practical tips on how to improve the configuration management process.

A common theme running among these tips is the partnering of configuration management personnel with other individuals—technical writers, documentation analysts, hardware and software suppliers, and the asset management group, for example—so that designers and analysts do not have to perform the tedious task of documenting complex configurations when, in all likelihood, they would much rather be implementing sophisticated systems. These partnerships were all discussed as part of the improvement proposals. We concluded with our usual assessment worksheets, which we can use to evaluate the configuration management process of an infrastructure.

1. Network equipment is usually not included as part of configuration management because there is little need to document network hardware. (True or False)

2. One of the most challenging of configuration management tasks involves the number, types, and features of desktop equipment. (True or False)

3. Which of the following is not a practical tip for improving configuration management?

a. involve appropriate hardware suppliers

b. involve appropriate business users

c. involve appropriate software suppliers

d. involve the asset management group for desktop equipment inventories

4. One of the concerns raised about the use of technical writers or documentation analysts is their _________ .

5. What role could hardware or software suppliers play in providing meaningful configuration documentation?