This last chapter of Part One presents three separate but related elements of managing today’s complex IT environments. These are the important aspects of ethics, legislation, and outsourcing, and they all involve highly intertwined human characteristics. The reason these are significant and timely is because each has come to influence how companies in general, and IT organizations in particular, are managed today.

The chapter begins with clear definitions of personal and business ethics. Next is a look at how several major corporations in the United States drastically compromised their business ethnics just after the turn of the new millennium. These breaches in ethical business behavior led to the prosecution and conviction of several chief executives and to the enactment of several pieces of far-reaching legislation.

The next segment of this chapter discusses some of these new laws that directly affect the accountability of corporate officers and their financial reporting; we also look at the IT systems that produce these reports. One of the results of these new ethical and legislative trends is that companies are considering the outsourcing of some or all of their IT processing. Finally, this chapter covers the implications of outsourcing.

This section describes the important role business ethics plays in managing complex organizations today and how this role impacts the management and delivery of IT offerings. Before initiating any discussion on ethics, it is helpful to first distinguish between personal ethics and business ethics. The following two definitions provide this distinction.

The personal ethics of an individual are usually developed early in one’s life. The values of honesty, trust, responsibility, and character are typically instilled in a person during childhood. But the degree to which these values are reinforced and strengthened during the trying years of adolescence and early adulthood vary from person to person. In some cases these early life traits may not always win out over the temptations of power, greed, and control.

Business ethics tend to focus on the behaviors of an individual as it pertains to his or her work environment. The differences between personal and business ethics may be at once both subtle and far-reaching.

For example, individuals who are unfaithful to their spouses will have compromised their personal ethics of trust and honesty. The number of people affected by such discretions may be few but the intense impact of the actions may very well be devastating, life altering, and even life-threatening. But if these same individuals embezzle huge sums of money from a corporation, the impact on a personal level may be felt less while the number of people affected—employees, investors, stockholders—could be substantial. Table 5-1 summarizes some of the major differences between a breach of personal ethics and a breach of business ethics.

Following the boom-and-bust dotcom craze of the first few years of the new millennium, a record number of major business scandals occurred in the United States. Tempted with over-inflated stock values, a lack of close government regulation, and a booming, optimistic economy, executives with questionable ethics took advantage of their situations. In 2002 alone, 28 Fortune 500 companies were found to be engaged in significant corporate scandals. The downfalls of the executives from these firms became very public in their coverage, devastating in their effect, and, in a few cases, stunning in their scope. As details of the criminal acts of these individuals emerged, it became apparent that corporate officers used a wide variety of accounting irregularities to enact their illegal schemes. The following list shows some of the more common of these uncommon practices:

• Overstating revenues

• Understating expenses

• Inflating profits

• Underreporting liabilities

• Misdirecting funds

• Artificially inflating stock prices

• Overstating the value of assets

Any number of fraudulent firms from this time period could be held up as instances of unethical business practices, but the following four serve as especially good examples: RadioShack, Tyco, WorldCom, and Enron.

The RadioShack Corporation, headquartered in Fort Worth, Texas, offers consumer electronics through hundreds of its retail stores. In May 2005, David Edmondson became RadioShack’s Chief Executive Officer (CEO) after having been groomed for the job for several years prior. The company did not fare well under Edmondson. Sales and stock prices both dropped. Employee morale was low, both for non-supervisory personnel whose employee stock purchase plan was cancelled and for managers who were subjected to a controversial ‘Fix 1500’ initiative in which the lowest-rated 1,500 store managers (out of 5,000) were on notice to improve or else.

Edmondson’s final undoing was due less to his corporate performance and more to a personal lack of ethics. Police arrested Edmondson for driving under the influence in early 2006 at about the same time reporters learned he had misstated his academic record on his resume. Edmondson claimed he had earned degrees in theology and psychology from the Heartland Baptist Bible College when, in fact, school records showed he had attended only two semesters and was never even offered a course in psychology. On February 20, 2006, a company spokesperson announced that David Edmondson had resigned over questions raised by his falsified resume. The company struggled through all of 2006 attempting to recover its financial health.

Edmondson’s civil indiscretions are small in comparison to the criminal behavior of other executives described in this section. Still, it points out how unethical behavior by even one key individual can have far-reaching effects on a company and its employees, including all those working in the IT department.

The scandal at Tyco International, a diversified manufacturing conglomerate whose products include toys, plastics, and household goods, was far more significant than that experienced by RadioShack and eventually led to criminal prosecutions. CEO L. Dennis Kozlowski and Chief Financial Officer (CFO) Mark Swartz had both enjoyed highly regarded business reputations before their fall from grace. In its January 14, 2002 edition, Business Week magazine even listed Kozlowski as one of the top 25 corporate managers of 2001. By September 2005 both were being led away in handcuffs to begin serving 8-1/3 to 25 years in prison.

On June 17, 2005, a Manhattan jury found Kozlowski and Swartz guilty of stealing more than US$150 million from Tyco. Specific counts included grand larceny, conspiracy, falsifying business records, and violating business law. Judge Michael J. Obus, who presided over the trial, ordered them to pay $134 million back to Tyco. In addition, the judge fined Kozlowski $70 million and Swartz $35 million.

The case came to represent the pervasive impression of greed and dishonesty that characterized many companies which enjoyed brief periods of prosperity through devious means. When some of Kozlowski’s extravagances came to light during trial, they served only to fuel this notion. Kozlowski had purchased a shower curtain for $6,000 and had thrown a birthday party for his wife on an Italian island for $2 million—all paid for with Tyco funds.

On November 10, 1997, WorldCom and MCI Communications merged to form the $37 billion company of MCI WorldCom, later renamed WorldCom. This was the largest corporate merger in U.S. history. The company’s bankruptcy filing in 2003 arose from accounting scandals and was symptomatic of the dotcom and Internet excesses of the late 1990s.

After its merger in 1997, MCI WorldCom continued with more ambitious expansion plans. On October 5, 1999, it announced a $129 billion merger agreement with Sprint Corporation. This would have made MCI WorldCom the largest telecommunications company in the U.S., eclipsing AT&T for the first time. But the U.S. Department of Justice and the European Union (EU), fearing an unfair monopoly, applied sufficient pressure to block the deal. On July 13, 2000, the Board of Directors of both companies acted to terminate the merger; later that year, MCI WorldCom renamed itself WorldCom.

The failure of the merger with Sprint marked the beginning of a steady downturn of WorldCom’s financial health. Its stock price was declining and banks were pressuring CEO Bernard Ebbers for coverage of extensive loans that had been based on over-inflated stock. The loans financed WorldCom expansions into non-technical areas, such as timber and yachting, that never proved to be profitable. As conditions worsened, Ebbers continued borrowing until finally WorldCom found itself in an almost untenable position. In April 2002, Ebbers was ousted as CEO and replaced with John Sidgmore of UUNet Technologies.

Beginning in 1999 and continuing through early 2002, the company used fraudulent accounting methods to hide its declining financial condition, presenting a misleading picture of financial growth and profitability. In addition to Ebbers, others who perpetuated the fraud include CFO David Sullivan, Controller David Myers, and the Director of General Accounting Buford Yates.

In June 2002, internal auditors discovered some $3.8 billion of fraudulent funds during a routine examination of capital expenditures and promptly notified the WorldCom board of directors. The board acted swiftly: Sullivan was fired, Myers resigned, and Arthur Anderson (WorldCom’s external auditing firm) was replaced with KPMG. By the end of 2003, it was estimated that WorldCom’s total assets had been inflated by almost $11 billion.

On July 21, 2002, WorldCom filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection in the largest such filing in U.S. history. The company emerged from bankruptcy as MCI in 2004 with approximately $5.7 billion in debt and $6 billion in cash. On February 14, 2005, Verizon Communications bought MCI for $7.6 billion. In December 2005, Microsoft announced MCI would join them by providing Windows Live Messenger customers with voice over the Internet protocol (VoIP) service for calls around the world. This had been MCI’s last totally new product, called MCI Web Calling, and has since been renamed Verizon Web Calling. It continues to be a promising product for future markets.

CEO Bernard Ebbers was found guilty on March 15, 2005, of all charges and he was convicted of fraud, conspiracy, and filing false documents with regulators. He was sentenced to 25 years in prison. He began serving his sentence on September 26, 2006, in Yazoo City, Mississippi. The other executives who conspired with Ebbers all pled guilty to various charges and were given slightly reduced sentences.

There are many lessons to be learned from this case, but two elements especially stand out:

- The fraudulent accounting was found during a routine examination of company records, indicating a fair degree of arrogance on the part of the conspirators as little was done to conceal the irregularities.

- It marked a rare instance of a reputable external accounting firm being involved, at least peripherally, with suspicious activities. But the tarnishing of Arthur Anderson’s reputation was only beginning (as we will see in the next section).

The most famous case of corporate fraud during this era was that of the Enron Energy Corporation headquartered in Houston, Texas. The fraud put both Enron and its external auditing firm out of business. Never before in U.S. business have two major corporations fallen more deeply or more quickly. This case epitomizes how severe the consequences can become as a result of unethical business practices.

Enron enjoyed profitable growth and a sterling reputation during the late 1990s. It pioneered and marketed the energy commodities business involving the buying and selling of natural gas, water and waste water, communication bandwidths, and electrical generation and distribution, among others. Fortune magazine named Enron “America’s Most Innovative Company” for six consecutive years from 1996 to 2001. It was on Fortune’s list of the “100 Best Companies to Work for in America” in 2000.

By 2001, however, Enron’s global reputation was becoming undermined by persistent rumors of bribery and strong-armed political tactics to secure contracts in Central America, South America, Africa, and the Philippines. In July 2001, Enron admitted to incurring a $102 million loss; in November of the same year, Enron admitted to hiding hundreds of millions more. By the end of 2001 the financial collapse of Enron was in full effect and its stock price plummeted to less than one dollar per share.

In 2002, a complex network of suspicious offshore partnerships and questionable accounting practices surfaced. The mastermind behind these activities was Enron CFO Andrew Fastow. He was indicted on November 1, 2002, by a federal grand jury in Houston on 78 counts, including fraud, money laundering and conspiracy. He and his wife, Lea Fastow, Enron’s former assistant treasurer, accepted a plea agreement on January 14, 2004. Andrew Fastow agreed to serve a 10-year prison sentence and pay $23.8 million in fines and his wife agreed to a five-month prison sentence. In exchange for their pleas, both would testify against other Enron corporate officers.

Federal prosecutors issued indictments against dozens of Enron executives. Key among these were Kenneth Lay, the former Chairman of the Board and CEO and Jeffrey Skilling, former CEO and Chief Operating Officer (COO). They were served in July 2004 with a 53-count, 63-page indictment covering a broad range of financial crimes. Among these were bank fraud, making false statements to banks and auditors, securities fraud, wire fraud, money laundering, conspiracy, and insider trading.

Lay pled not guilty to his 11 criminal charges, claiming he had been misled by those around him. His wife, Linda Lay, also claimed innocence to a bizarre set of associated circumstances. On November 28, 2001, Linda Lay sold approximately 500,000 shares of her Enron stock (when its value was still substantial) some 15 minutes before news was made public that Enron was collapsing, at which time the stock price plummeted to less than one dollar per share.

After a highly visible and contentious trial of Lay and Skilling, the jury returned its verdicts on May 25, 2006. Skilling was convicted on 19 of 28 counts of securities fraud and wire fraud and was acquitted on the remaining nine, including insider trading. He was sentenced to 24 years, 4 months in prison, which he began serving on October 23, 2006. Skilling was also ordered to pay $26 million of his own money to the Enron pension. Kenneth Lay was convicted of all six counts of securities and wire fraud and sentenced to 45 years in prison. On July 5, 2006, he died at age 64 after suffering a heart attack the day before.

Corporate officers from Enron were not the only ones to suffer the consequences of the scandal. On June 15, 2002, Arthur Andersen was convicted of obstruction of justice for shredding documents related to its audit of Enron. On May 31, 2005, the Supreme Court of the United States unanimously overturned Andersen’s conviction due to flaws in the jury obstructions. Despite this ruling, it is highly unlikely Andersen will ever return as a viable business.

Arthur Andersen was founded in 1913 and enjoyed a highly regard reputation for most of its history. But the firm lost nearly all of its clients after its Enron indictment and there were more than 100 civil suits brought against it related to its audits of Enron and other companies, including WorldCom. From a peak of 28,000 employees in the United States and 85,000 worldwide, the firm now employs roughly 200 people, most of whom are based in Chicago and still handle the various lawsuits. Andersen was considered one of the Big Five large international accounting firms (as listed below); with Andersen’s absence, this list has since been culled to Big Four.

• Arthur Andersen

• Deloitte & Touche

• Ernst & Young

• KPMG

• PricewaterhouseCoopers

What made the Enron scandal particularly galling to its victims and its observers was that only a few months prior to Enron’s collapse, corporate officers assured employees that their stock options, their benefits, and their pensions were all safe and secure. Many employees were tempted to pull their life savings out of what they felt was a failing investment. But the convincing words of Kenneth Lay and the employees’ own misplaced loyalty to their company dissuaded them from doing so. In the end, thousands of employees lost most, if not all, of their hard-earned savings.

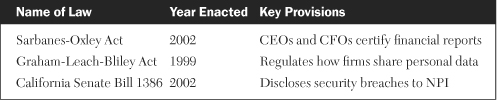

In response to these various accounting scandals and other concerns of the consuming public, the U.S. Congress and state legislators passed a series of laws to place greater governance on corporations. Lawmakers passed dozens of bills to address these concerns and three of these laws (see Table 5-2) had particular impact on IT organizations: The Sarbanes-Oxley Act, the Graham-Leach-Bliley Act, and California Senate Bill 1386.

If there is one single act of U.S. legislation that is known for its direct response to the various scandals of the early 21st century, it is the Sarbanes-Oxley Act. The name comes from the sponsors of the legislation, Senator Paul Sarbanes (Democrat-Maryland) and Representative Michael G. Oxley (Republican-Ohio). The law is also known by its longer name, The Public Company Accounting Reform and Investor Protection Act of 2002, or by its more common shorter name of SOX. The numerous corporate scandals caused a decline of public trust in accounting and reporting practices; SOX was intended to restore that trust. The Enron scandal was not the only impetus behind this law, but it certainly served as its catalyst. The law passed overwhelmingly on July 30, 2002, with a House vote of 423 to 3 and a Senate vote of 99 to 0.

The Act contains 11 titles, or sections, ranging from additional corporate board responsibilities to criminal penalties and it requires the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to implement rulings on requirements to comply with the new law. The following list details some of the other major provisions of SOX.

• Creation of a Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB)

• Stronger penalties for fraud

• Public companies cannot make loans to management

• Report more information to the public

• Maintain stronger independence from external auditors

• Report on and have audited financial reporting controls

Two of the more controversial parts of SOX are sections 302 and 404.

Section 302 mandates that companies establish and maintain a set of internal procedures to ensure accurate financial reporting. The signing officers must certify that such controls are in existence and are being used, and within 90 days of the signing, they must certify that they have evaluated the effectiveness of the controls.

Section 404 requires corporate officers to report their conclusions in the annual Exchange Act report about the effectiveness of their internal financial reporting controls. Failure of the controls being effective, or failure of the officers to report on the controls, could result in criminal prosecution. For many companies, a key concern is the cost of updating information systems to comply with the control and reporting requirements. Systems involving document management, access to financial data, or long-term data storage must now provide auditing capabilities which were never designed into the original systems.

The financial reporting processes of most companies are driven by IT systems, and the Chief Information Officer (CIO) is responsible for the security, accuracy, and reliability of the systems that manage and report on financial data. Systems such as enterprise resource planning (ERP) and customer relationship management (CRM) are deeply integrated with the processing and reporting of financial data. As such, they are intertwined with the overall financial reporting process and fall under the requirement of compliance with SOX. Many companies now require not only the CEO and CFO to sign-off on SOX compliance reports, but CIOs as well. Several CIOs are also asking subordinate managers to sign off on SOX reports. Many of the processes discussed in this book—such as availability, production acceptance and security—have direct bearing on SOX compliance.

Other countries have now begun instituting SOX-like legislation to prevent the type of accounting scandals experienced in the United States. For example, CSOX is the Canadian version of SOX. In line with Sarbanes-Oxley, South Korea has begun debating the establishment a separate, regulatory body similar to the PCAOB (Public Company Accounting Oversight Board). Foreign countries doing business with American companies have learned it is prudent to be both knowledgeable and compliant with SOX provisions.

The Graham-Leach-Bliley Act, also known as the Financial Modernization Act, regulates the sharing of personal information about individuals who are doing business with financial institutions. The law requires financial companies to inform their customers about the company’s privacy policies and practices, especially as it relates to non-public information (NPI). Based on these policies and practices, customers can then decide whether or not they want to do business with the company.

The law also gives consumers additional control over how financial institutions will use and share the personal information of consumers. It does this by requiring a financial company to offer consumers an ‘opt-out’ clause. This clause empowers consumers to choose whether or not they want to have their personal information shared with other companies. If consumers elect to exercise their opt-out clause, the financial institution with whom they are doing business cannot share their personal information with any other organization.

California Senate Bill 1386 is also known as California SB 1386. It requires that any business, individual, or state agency conducting business in the state of California disclose any breaches of security of computerized NPI to all individuals with whom they conduct business. Because of the large numbers of companies that process and store the NPI of customers, this law has far-reaching effects. It also places a high premium on the security processes used by IT to ensure the likelihood of such a breach is kept to an absolute minimum. The law also means information systems must be readily able to contact all customers on a moment’s notice should even a single compromise of NPI occur.

If a bank, for example, unintentionally discloses a customer’s credit card number, the bank must disclose to all of its customers the nature of the security breach, how it happened, the extent of exposure, and what is being done to prevent its reoccurrence. This very scenario happened to Wells Fargo bank in 2003. Sensitive customer information was put at risk when an employee’s laptop on which it resided was stolen. The CEO of the bank sent out a letter to the bank’s tens of thousands of customers explaining what happened, how it happened, and what was being done to prevent it from happening again.

Because of this increased accountability of corporate executives and their IT reporting systems, many organizations consider outsourcing some or all of their IT functions. There certainly are other factors that come in to play when making an IT outsourcing decision. Chief among these are the overall cost savings and other benefits to be realized versus some of the drawbacks to outsourcing. The following list describes some of the more common factors. But the additional responsibilities of legislation, such as those mandated by Sarbanes-Oxley, cause many a CEO to look seriously at outsourcing their IT environments.

• Overall cost savings

• Scalability of resources

• Potential loss of control

• Total cost of maintaining an outsourcing agreement

• Credibility and experience of outsourcer

• Possible conflicts of priority

• Geographic and time-zone differences

• Language barriers

• Cultural clashes

The effects of outsourcing an IT organization varies from company to company. The effects also depend on whether all or only parts of the IT department are outsourced. Many companies today outsource their call centers or service desks to locations such as India or the Philippines. Other companies keep service-oriented functions (such as call centers) but outsource programming or web development to countries such as Vietnam or South Korea.

Regardless of how much of an IT organization is outsourced, there remain benefits of maintaining high ethical standards. When evaluating which particular outsourcer to use, many companies today include compliance to SOX-like legislation involving corporate governance as part of the selection criteria. One key lesson the recent business scandals taught very well was that violating basic business ethics seems to always result in far greater long-term losses than whatever short-term gains they may have provided.

This chapter described the significance and the relationships of ethics, legislation, and outsourcing in managing today’s complex IT environments. The chapter offered definitions of personal and business ethics and described how the lack of them led to the undoing of several executives and the corporations they ran. Further discussions showed how these breaches of corporate ethics led to the enactment of several pieces of far-reaching legislation.

The second segment of this chapter explained some of these new laws and how they impact the accountability of corporate officers and of the reporting of their company’s finances. This additional accountability and governance directly affects the IT organization, its managers, and the systems that produce the financial reports. The chapter concluded with the topic of outsourcing and how it is sometimes considered as a response to these new laws of accountability.

1. The differences between personal and business ethics are both subtle and far-reaching. (True or False)

2. CIOs play only a very small role in ensuring compliance to the Sarbanes-Oxley Act. (True or False)

3. Corporate business scandals of U.S. companies between 2002 and 2007:

a. were neither civil nor criminal in nature

b. were only civil in nature

c. were only criminal in nature

d. were both civil and criminal in nature

4. The Graham-Leach-Bliley Act regulates the sharing of ___________ .

5. What are some of the advantages and disadvantages of outsourcing?