No discussion about the important role people play in systems management would be complete without looking at the topic of customer service. This chapter details the full spectrum of customer service within an infrastructure organization. It begins by describing how IT has evolved into a service industry and how this influences the culture and hiring practices of successful companies.

Next, we present techniques on how to identify who your real customers are and how to effectively negotiate realistic service expectations. Toward the end of the chapter we describe the four cardinal sins that almost always undermine good customer service in an IT environment.

Most IT organizations began as offshoots of their company’s accounting departments. As companies grew and their accounting systems became more complex, their dependency on the technology of computers also grew. The emphasis of IT in the 1970s was mostly on continually providing machines and systems that were bigger, faster, and cheaper. During this era, technological advances in IT flourished. Two factors led to very little emphasis on customer service.

- In the 1970s, the IT industry was still in its infancy. Organizations were struggling just to stay abreast of all the rapidly changing technologies, let alone focus on good customer service.

- Within most companies the IT department was the only game in town, so to speak. Departments that were becoming more and more dependent on computers—finance, engineering, and administration, for example—were pretty much at the mercy of their internal IT suppliers, regardless of how much or how little customer service was provided.

By the 1980s, the role of IT and customer service began changing. IT was becoming a strategic competitive advantage for many corporations. A few industries, such as banking and airlines, had long before discovered how the quality of IT services could affect revenue, profits, and public image. As online applications started replacing many of the manual legacy systems, more and more workers became exposed to the power and the frustration of computers. Demand for high availability, quick response, and clear and simple answers to operational questions gave rise to user groups, help desks, service level agreements (SLAs), and eventually customer service representatives—all within the confines of a corporate structure.

Good customer service was now becoming an integral part of any well-managed IT department. By the time the 1990s rolled around, most users were reasonably computer literate; PCs and the Internet were common fixtures in the office and at home; and the concept of customer service transitioned from being hoped for to being expected. Demands for excellent customer service grew to such a degree in the 1990s that the lack of it often led to demotions, terminations, and outsourcing.

Whether IT professionals were prepared for it or not, IT had evolved from a purely accounting and technical environment into a totally service-oriented one. Companies hiring IT professionals now often require employees to have traits such as empathy, helpfulness, patience, resourcefulness, and a sense of teamwork. The extent to which these traits are in evidence frequently determines an individual’s, or an organization’s, success in IT today.

There are four elements of good customer service:

• Identifying your key customers

• Identifying key services of key customers

• Identifying key processes that support key services

• Identifying key suppliers that support key processes

We’ll discuss the first two at length and briefly describe the last two.

One of the best ways to ensure you are providing excellent customer service is to consistently meet or exceed the expectations of your key customers. In transitioning to a service-oriented environment, infrastructure professionals sometimes struggle with identifying who their key customers are. I frequently hear this comment:

Since most all company employees in one way or another use IT services, then all company employees must be our key customers.

In reality, there are usually just a small number of key representative customers who can often serve as a barometer for good customer service and for effective process improvements. For example, you may design a change management process that dozens or even hundreds of programmers may be required to use. But you would probably need to involve only a handful of key programmer representatives to assist in designing the process and measuring its effectiveness.

There are various criteria to help in determining which of your numerous customers qualify as key customers. An IT department should identify those criteria that are the most suitable for identifying the key customers in their particular environment. The following list summarizes characteristics of key customers of a typical infrastructure:

- Someone whose success critically depends on the services you provide.

Infrastructure groups typically serve a variety of departments in a company. Some departments are more essential to the core business of the company than others, just as some applications are considered mission critical while others aren’t. The heads or designated leads of these departments are usually good candidates for key customers.

- Someone who, when satisfied, assures your success as an organization.

Some individuals hold positions of influence in a company and can help market the credibility of an infrastructure organization. These customers may be in significant staff positions, such as those found in legal or public affairs departments. The high visibility of these positions may afford them the opportunity to highlight IT infrastructure achievements to other non-IT departments. These achievements could include high availability of online systems or the reliable restorations of inadvertently deleted data.

- Someone who fairly and thoroughly represents large customer organizations.

The very nature of some of the services provided by IT infrastructures results in these services being used by a large majority of a company’s workforce. These highly used services include email, Internet, and intranet services. An analysis of the volume of use of these services by departments can determine which groups are using which services the most. The heads or designated leads of these departments would likely be good key customer candidates.

- Someone who frequently uses, or whose organization frequently uses, your services.

Some departments are major users of IT services by nature of their relationship within a company. In an airline company, it may be the department in charge of the reservation system. For a company supplying overnight package deliveries, the key department may be the one overseeing the package tracking system. During the time I headed the primary IT infrastructure groups at a leading defense contractor and later at a major motion picture studio, I witnessed firsthand the key IT user departments—design engineering (defense contractor) and theatrical distribution (motion picture company). Representatives from each group were solid key-customer candidates.

- Someone who constructively and objectively critiques the quality of your services.

It’s possible that a key customer may be associated with a department that does not have a critical need for or high-volume use of IT services. A noncritical and low-volume user may qualify as a key customer because of a keen insight into how an infrastructure could effectively improve its services. These individuals typically have both the ability and the willingness to offer candid, constructive criticism about how to improve IT services.

- Someone who has significant business impact on your company as a corporation.

Marketing or sales department representatives in a manufacturing firm may contain key customers of this type. In aerospace or defense contracting companies, it may be advanced technology groups. The common thread among these key customers is that their use of IT services can greatly advance the business position of the corporation.

- Someone with whom you have mutually agreed-upon reasonable expectations.

Most any infrastructure user, both internal and external to either IT or its company, may qualify as a key customer if the customer and the IT infrastructure representative have reasonable expectations that are mutually agreed upon. Conversely, customers whose expectations are not reasonable should usually be excluded as key customers. The adage about the squeaky wheel getting the grease does not always apply in this case—I have often seen just the reverse. In many cases, the customers with the loud voices insisting on unreasonable expectations are often ignored in favor of listening to the constructive voices of more realistic users.

The next step after identifying your key customers is to identify their key services. This may sound obvious but in reality many infrastructure managers merely presume to know the key IT services of their key customers without ever verifying which services they need the most. Only by interacting directly with their customers can these managers understand the wants and needs of their customers.

Infrastructure managers need to clearly distinguish between services their customers need to conduct the business of their departments and services that they want but may not be able to cost-justify to the IT organization. For example, an engineering department may need to have sophisticated graphics software to design complex parts and may want to have all of the workstation monitors support color. The IT infrastructure may be able to meet their expectations of the former but not the latter. This is where the importance of negotiating realistic customer expectations comes in.

The issue of reasonable expectations is a salient point and cuts to the heart of sound customer service. When IT people started getting serious about service, they initially espoused many of the tenets of other service industries. Phrases such as the following were drilled into IT professionals at several of the companies where I was employed:

The customer is always right.

Never say no to a customer.

Always meet your customers’ expectations.

As seemingly obvious as these statements appear, the plain and simple fact is that rarely can you meet all of the expectations of all of your customers all of the time. The more truthful but less widely acknowledged fact is that customers sometimes are unreasonable in their expectations. IT service providers may actually be doing more of a disservice to their customers and to themselves by not saying no to an unrealistic demand. This leads to the first of two universal truths I have come to embrace about customer service and expectations.

An unreasonable expectation, rigidly demanded by an uncompromising customer and naively agreed to by a well-intentioned supplier, is one of the major causes of poor customer service.

I have observed this scenario time and time again within IT departments throughout various industries. In their zest to please customers and establish credibility for their organizations, IT professionals agree to project schedules that cannot be met, availability levels that cannot be reached, response times that cannot be obtained, and budget reductions that cannot be reached. Knowing when and how to say no to a customer is not an easy task, but there are techniques available to assist in negotiating and managing realistic expectations.

While heading up an extensive IT customer service effort at a major defense contractor, I developed with my team a simple but effective methodology for negotiating and managing realistic customer expectations. The first part involved thorough preparation of face-to-face interviews with selected key customers; the second part consisted of actually conducting the interview to negotiate and follow up on realistic expectations.

Changing the mindset of IT professionals can be a challenging task. We were asking them to focus very intently on a small number of customers when for years they had emphasized doing almost the exact reverse. The criteria covered in the previous section helped immensely to limit their number of interviews to just a handful of key customers.

Getting the IT leads and managers to actually schedule the interviews was even more of a challenge for us. This reluctance to interview key customers was puzzling to our team. These IT professionals had been interviewing many new hires for well over a year and had been conducting semiannual performance reviews for most all of their staffs for some time. Yet we were hearing almost every excuse under the sun as to why they could not conduct a face-to-face interview with key customers. Some wanted to conduct it over the phone, some wanted to send out surveys, others wanted to use email, and many simply claimed that endless phone tag and schedule conflict prevented successful get-togethers.

We knew that these face-to-face interviews with primary customers were the key to successfully negotiating reasonable expectations that, in turn, would lead to improved customer service. So we looked a little closer at the reluctance to interview. What we discovered really surprised us. Most of our managers and leads believed the interviews could easily become confrontational unless only a few IT-friendly customers were involved. Many had received no formal training on effective interviewing techniques and felt ill-equipped to deal with a potentially belligerent user. Very few thought that they could actually convince skeptical users that some of their expectations may be unrealistic and yet still come across as being service-oriented.

This turn of events temporarily changed our approach. We immediately set up an intense interview training program for our lead and managers. It specifically emphasized how to deal with difficult customers. Traditional techniques (such as open-ended questions, active listening, and restatements) were combined with effective ways to cut off ramblers and negotiate compromise, along with training on when to agree to disagree. We even developed some sample scripts for them to use as guidelines.

The training went quite well and proved to be very effective. Leads and managers from all across our IT department began to conduct interviews with key customers. From the feedback we received from both the IT interviewers and our customers, we learned what the majority felt were the most effective parts of the interview. We referred to them as validate, negotiate, and escalate:

• Validate. Within the guidelines of the prepared interview scripts, the interviewers first validated their interviewees by assuring them that they were, in fact, key customers. They then told the customers that they did indeed critically need and use the services that we were supplying. Interviewers then went on to ask what the customers’ current expectations were for the levels of service provided.

• Negotiate. If customers’ expectations were reasonable and obtainable, then the parties discussed and agreed upon the type and frequency of measurements to be used. If the expectations were not reasonable, then negotiations, explanations, and compromises were proposed. If these negotiations did not result in a satisfactory agreement, as would occasionally occur, then the interviewer would politely agree to disagree and move on to other matters.

• Escalate. Next the interviewer would escalate the unsuccessful negotiation to his or her manager, who would attempt to resolve it with the manager of the key customer.

The validate/negotiate/escalate method proved to be exceptionally effective at negotiating reasonable expectations and realistic service levels. The hidden benefits included clearer and more frequent communication with users, improved interviewing skills for leads and managers, increased credibility for the IT department, and more empathy of our users for some of the many constraints under which most all IT organizations work.

This empathy that key customers were sharing with us leads me to the second universal truth I embrace concerning customer service and expectations:

Most customers are forgiving of occasional poor service if reasonable attempts are made to explain the nature and cause of the problem and what is being done to resolve it and prevent its future occurrence.

As simple and as obvious as this may sound, it still amazes me to see how often this basic concept is overlooked or ignored in IT organizations. We would all be better served if it was understood and used more frequently.

Negotiating realistic expectations of service leads into the third element of good customer service: identifying key processes. These processes comprise the activities that provide and support the key services of the customers. For example, a legal department may need a service to retrieve records that have been archived months previously. In this case, the activities of backing up the data, archiving and storing it offsite, and retrieving it quickly for customer access would be the key processes that support this key service.

Similarly, a human resources department may need a service that safeguards the confidentiality of payroll and personnel data. In this case, the processes that ensure the security of the data involved would be key.

Identifying key suppliers is the fourth element of good customer service. Key suppliers are those individuals who provide direct input, in terms of products or support, to the key processes. In our example in the prior section regarding the legal department, some of the key suppliers would be the individuals responsible for storing the data offsite and for retrieving it back to make it accessible for users. Similarly for the human resources example, the developers of the commercial software security products and the individuals responsible for installing and administering the products would be key suppliers for the data-security processes.

As we have discussed, the four key components of good customer service are identifying key customers, identifying key services of these customers, identifying key processes, and identifying key suppliers. Understanding the relationships between these four entities can go a long way to ensuring high levels of service quality.

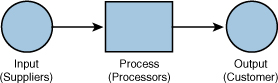

Figure 4-1 shows the traditional model of a basic work-flow process. Suppliers provide input of some type into a process. In the case of an IT production control department this could be data being fed into a program stream that is part of a job execution process, or it could be database changes being fed into a quality-assurance process. The output of the first process may be updated screens or printed reports for users; the output of the second process would be updated database objects for programmers.

The problem with the traditional work-flow model is that it does not encourage any collaboration between suppliers, processors, and customers, nor does it measure anything about the efficiency of the process or the effectiveness of the service.

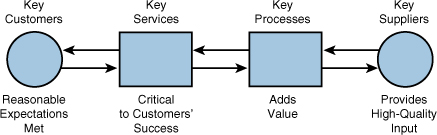

In Figure 4-2, the model is revised in several aspects to improve the quality of customer service. First, a key services box has been added to emphasize that the output of the process should result in a deliverable and measurable service that is critical to the success of the customer. Second, the flow of work between all four elements is shown going both ways to stress the importance of two-way communication between the individuals involved with each element. Third, each of the elements are designated as key elements to highlight the fact that, while many customers and suppliers may be involved in a particular work-flow process, there are usually only a handful that significantly affect the quality of input and output.

A narrative interpretation of the Figure 4-2 work-flow model in each direction may serve to clarify its use and importance. We will start first in the right-to-left direction. Key suppliers provide high-quality input into a key process. The streamlined key process acts upon the high-quality input, ensuring that each step of the activity adds value to the process; this results in delivering a key service to a key customer.

Next we will go in the left-to-right direction. We start by identifying a key customer and then interviewing and negotiating reasonable expectations with this customer. The expectations should involve having key services delivered on time and in an acceptable manner. These services are typically critical to the success of the customer’s work. Once the key services are identified, the key processes that produce these services are next identified. Finally, having determined which key processes are needed, the key suppliers that input to these processes are identified.

The revised work-flow model shown in Figure 4-2 serves as the basis for a powerful customer service technique we call a customer/supplier matrix. It involves identifying your key services, determining the key customers of those services, seeing which key processes feed into the key services, and identifying the key suppliers of these key processes. A more succinct way of saying this is:

Know who is using what and how it’s being supplied.

The who refers to your key customers. The what refers to your key services. The how refers to your key processes. The supplied refers to your key suppliers.

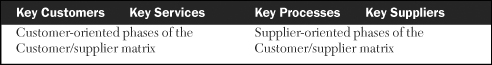

Table 4-1 shows how a matrix of this type could be set up. The matrix comprises four partitions, each representing a key element of the relationship. The leftmost partition represents customers whose use of IT services is critical to their success and whose expectations are reasonable. The partition to the right of the customer box contains the IT services that are critical to a customer’s success and whose delivery meets customer expectations. The next partition to the right shows the processes that produce the key services required by key customers. The last partition represents the suppliers who feed into the key processes.

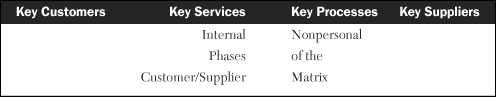

Table 4-2 shows how the matrix is divided into two major partitions. The left half represents the customer-oriented phases and the right half represents the supplier-oriented phases.

Table 4-3 shows the two phases representing the human interaction phases. These are sometimes referred to as the external phases of the matrix.

Table 4-4 shows the two nonpersonal phases of the matrix representing process, technology, and automation. These are sometimes referred to as the internal phases of the matrix.

A worthwhile enhancement to the basic customer/supplier matrix is shown in Table 4-5. Here we add service and process metrics. The service metrics are negotiated with key customers to measure the quality of the services delivered as seen through the eyes of the customer. The process metrics are negotiated with key suppliers to measure the quality of the input they provide into key processes.

During my many years directing and consulting on infrastructure activities, I often lead teams in search of how to improve the quality of good customer service. While these efforts produced many excellent suggestions on what to do right, including the use of the customer/supplier matrix, they also uncovered several common tendencies to avoid. I refer to these inadvertent transgressions as the four cardinal sins that undermine good customer service:

- Presuming your customers are satisfied because they are not complaining.

No news is good news? Nothing could be further from the truth when it comes to customer service. Study after study has shown—and my own personal experience has confirmed—that the overwhelming majority of customers do not complain about poor service. They usually go elsewhere, find alternate means, complain to other users, or suffer silently in frustration. That is why proactively interviewing your key customers is so important.

- Presuming that you have no customers.

IT professionals working within their infrastructure sometimes feel they have no direct customers because they seldom interact with outside users. But they all have customers who are the direct recipients of their efforts. In the case of the infrastructure, many of these recipients are internal customers who work within IT, but they are customers nonetheless and need to be treated to the same high level of service as external customers.

The same thinking applies to internal and external suppliers. Just because your direct supplier is internal to IT does not mean you are not entitled to the same high-quality input that an external supplier would be expected to provide. One final but important thought on this is that you may often be an internal customer and supplier at the same time and need to know who your customers and suppliers are at different stages of a process.

- Measuring only what you want to measure to determine customer satisfaction.

Measurement of customer satisfaction comes from asking key customers directly just how satisfied are they with the current level of service. In addition to that, service and quality measurements should be based on what a customer sees as service quality, not on what the supplier thinks.

- Presuming that written SLAs will solve problems, prevent disputes, and ensure great customer service.

A written SLA is only as effective as the collaboration with the customer that went into it. Effective SLAs need to be developed jointly with customer and support groups; they must be easily, reliably, and accurately measured; and they must be followed up with periodic customer meetings.

This chapter showed the importance of providing good customer service and the value of partnering with key suppliers. It presented how to identify key customers and the key services they use. I discussed how to negotiate realistic service levels and looked at two universal truths about customer service and expectations. Next I showed how to develop a customer/supplier matrix. Finally, I provided a brief discussion about the four cardinal sins that undermine good customer service.

1. By the start of the 1990s, most users were still not very computer literate. (True or False)

2. Service providers typically need just a small number of key representative customers to serve as a barometer of good customer service. (True or False)

3. Which of the following is not a key element of good customer service?

a. identifying your key customers

b. identifying key complaints of key customers

c. identifying key services of key customers

d. identifying key processes that support key services

4. The decade in which the primary roles of IT and customer service began changing was the ___________.

5. Develop reasons why the adage about the squeaky wheel always getting the grease is either good or bad for high-quality customer service.