CHAPTER 3

FINANCIAL REPORTING STANDARDS

After completing this chapter, you will be able to do the following:

- Describe the objective of financial statements and the importance of financial reporting standards in security analysis and valuation.

- Describe the roles and desirable attributes of financial reporting standard-setting bodies and regulatory authorities in establishing and enforcing reporting standards, and describe the role of the International Organization of Securities Commissions.

- Describe the status of global convergence of accounting standards and ongoing barriers to developing one universally accepted set of financial reporting standards.

- Describe the International Accounting Standards Board’s conceptual framework, including the objective and qualitative characteristics of financial statements, required reporting elements, and constraints and assumptions in preparing financial statements.

- Describe general requirements for financial statements under IFRS.

- Compare key concepts of financial reporting standards under IFRS and U.S. GAAP reporting systems.

- Identify the characteristics of a coherent financial reporting framework and the barriers to creating such a framework.

- Explain the implications for financial analysis of differing financial reporting systems and the importance of monitoring developments in financial reporting standards.

- Analyze company disclosures of significant accounting policies.

Financial reporting standards provide principles for preparing financial reports and determine the types and amounts of information that must be provided to users of financial statements, including investors and creditors, so that they may make informed decisions. This chapter focuses on the framework within which these standards are created. An understanding of the underlying framework of financial reporting standards, which is broader than knowledge of specific accounting rules, will allow an analyst to assess the valuation implications of financial statement elements and transactions—including transactions, such as those that represent new developments, which are not specifically addressed by the standards.

Section 2 of this chapter discusses the objective of financial statements and the importance of financial reporting standards in security analysis and valuation. Section 3 describes the roles of financial reporting standard-setting bodies and regulatory authorities and several of the financial reporting standard-setting bodies and regulatory authorities. Section 4 describes the trend toward and barriers to convergence of global financial reporting standards. Section 5 describes the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) framework1 and general requirements for financial statements. Section 6 discusses the characteristics of an effective financial reporting framework along with some of the barriers to a single coherent framework. Section 7 illustrates some of the specific differences between IFRS and U.S. generally accepted accounting practices (U.S. GAAP), and Section 8 discusses the importance of monitoring developments in financial reporting standards. Section 9 summarizes the key points of the chapter, and practice problems in the CFA Institute multiple-choice format conclude the chapter.

2. THE OBJECTIVE OF FINANCIAL REPORTING

The financial reports of a company include financial statements and other supplemental disclosures necessary to assess a company’s financial position and periodic financial performance. Financial reporting is based on a simple premise. The International Accounting Standards Board (IASB), which sets financial reporting standards that have been adopted in many countries, expressed it as follows in its Conceptual Framework for Financial Reporting 2010 (Conceptual Framework 2010):2

The objective of general purpose financial reporting is to provide financial information about the reporting entity that is useful to existing and potential investors, lenders, and other creditors in making decisions about providing resources to the entity. Those decisions involve buying, selling or holding equity and debt instruments, and providing or settling loans and other forms of credit.3

The objective in the Conceptual Framework (2010) differs from the objective of the Framework for the Preparation and Presentation of Financial Statements (1989)4 in a number of key ways. The scope of the objective now extends to financial reporting, which is broader than the previously stated scope that covered financial statements only. Another difference is that the objective now specifies the primary users for whom the reports are intended (existing and potential investors, etc.) while the previously stated objective referred solely to a “wide range of users.” Also, while the Conceptual Framework (2010) identifies information that should be reported—including that about financial position (economic resources and claims), changes in economic resources and claims, and financial performance reflected by accrual accounting and past cash flows—it does not list that information within the objective itself, unlike the previously stated objective.

Standards are developed in accordance with a framework so it is useful to have an agreed upon framework to guide the development of standards. The IASB and the U.S. Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) joint conceptual framework project aims to develop a common foundation for standards. Standards based on this foundation should be principles-based, internally consistent, and converged. Until recently, financial reporting standards were primarily developed independently by each country’s standard-setting body. This independent standard setting created a wide range of standards, some of which were quite comprehensive and complex (often considered to be rules-based standards), and others more general (often considered to be principles-based standards). Recent accounting scandals and the economic crisis of 2008–2009 increased awareness of the need for high quality, more uniform global financial reporting standards and provided the impetus for stronger coordination among the major standard-setting bodies. Such coordination is also a natural outgrowth of the increased globalization of capital markets.

Developing financial reporting standards is complicated because the underlying economic reality is complicated. The financial transactions and financial position that companies aim to represent in their financial reports are also complex. Furthermore, uncertainty about various aspects of transactions often results in the need for accruals and estimates, both of which necessitate judgment. Judgment varies from one preparer to the next. Accordingly, standards are needed to achieve some amount of consistency in these judgments. Even with such standards, there usually will be no single correct answer to the question of how to reflect economic reality in financial reports. Nevertheless, financial reporting standards try to limit the range of acceptable answers in order to increase consistency in financial reports.

The IASB and the FASB have developed similar financial reporting frameworks that specify the overall objective and qualities of information to be provided. Financial reports are intended to provide information to many users, including investors, creditors, employees, customers, and others. As a result of this multipurpose nature, financial reports are not designed solely with asset valuation in mind. However, financial reports provide important inputs into the process of valuing a company or the securities a company issues. Understanding the financial reporting framework—including how and when judgments and estimates can affect the numbers reported—enables an analyst to evaluate the information reported and to use the information appropriately when assessing a company’s financial performance. Clearly, such an understanding is also important in assessing the financial impact of business decisions by, and in making comparisons across entities.

EXAMPLE 3-1 Estimates in Financial Reporting

To facilitate comparisons across companies (cross sectional analysis) and over time for a single company (time series analysis), it is important that accounting methods are comparable and consistently applied. However, accounting standards must be flexible enough to recognize that differences exist in the underlying economics between businesses.

Suppose two companies buy the same model of machinery to be used in their respective businesses. The machine is expected to last for several years. Financial reporting standards typically require that both companies account for this equipment by initially recording the cost of the machinery as an asset. Without such a standard, the companies could report the purchase of the equipment differently. For example, one company might record the purchase as an asset and the other might record the purchase as an expense. An accounting standard ensures that both companies should record the transaction in a similar manner.

Accounting standards typically require the cost of the machine to be apportioned over the estimated useful life of an asset as an expense called depreciation. Because the two companies may be operating the machinery differently, financial reporting standards must retain some flexibility. One company might operate the machinery only a few days per week, whereas the other company operates the equipment continuously throughout the week. Given the difference in usage, it would not be appropriate to require the two companies to report an identical amount of depreciation expense each period. Financial reporting standards must allow for some discretion such that management can match their financial reporting choices to the underlying economics of their business while ensuring that similar transactions are recorded in a similar manner between companies.

Financial statements of two companies with identical transactions in the fiscal year, prepared in accordance with the same set of financial reporting standards, are most likely to be:

A. Identical.

B. Consistent.

C. Comparable.

Solution: C is correct. The companies’ financial statements should be comparable (possible to compare) because they should reflect the underlying economics of the transactions for each company. The underlying economics may vary between companies, so the financial statements are not likely to be identical. Choices made by each company with respect to accounting methods should be consistent but the choice across companies is not necessarily consistent. Information about accounting choices will enhance a user’s ability to compare the companies’ financial statements.

3. STANDARD-SETTING BODIES AND REGULATORY AUTHORITIES

A distinction must be made between standard-setting bodies and regulatory authorities. Standard-setting bodies, such as the IASB and FASB, are typically private sector, self-regulated organizations with board members who are experienced accountants, auditors, users of financial statements, and academics. The requirement to prepare financial reports in accordance with specified accounting standards is the responsibility of regulatory authorities. Regulatory authorities, such as the Accounting and Corporate Regulatory Authority in Singapore, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) in the United States, the Securities and Exchange Commission in Brazil, and the Financial Service Authority (FSA) in the United Kingdom (a new regulatory authority will succeed the FSA in the United Kingdom as of 2012), are governmental entities that have the legal authority to enforce financial reporting requirements and exert other controls over entities that participate in the capital markets within their jurisdiction.

In other words, generally, standard-setting bodies set the standards and regulatory authorities recognize and enforce the standards. Without the recognition of the standards by the regulatory authorities, the private sector standard-setting bodies would have no authority. Note, however, that regulators often retain the legal authority to establish financial reporting standards in their jurisdiction and can overrule the private sector standard-setting bodies.

EXAMPLE 3-2 Industry-Specific Regulation

In certain cases, multiple regulatory bodies affect a company’s financial reporting requirements. For example, in almost all jurisdictions around the world, banking-specific regulatory bodies establish requirements related to risk-based capital measurement, minimum capital adequacy, provisions for doubtful loans, and minimum monetary reserves. An awareness of such regulations provides an analyst with the context to understand a bank’s business, including the objectives and scope of allowed activities. Insurance is another industry where specific regulations typically are in place. An analyst should be aware of such regulations to understand constraints on an insurance company.

The following are examples of country-specific bank regulators. In Canada, the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions regulates and supervises all banks in Canada as well as some other federally incorporated or registered financial institutions or intermediaries. In Germany, the German Federal Financial Supervisory Authority exercises supervision over financial institutions in accordance with the Banking Act. In Japan, the Financial Services Agency has regulatory authority over financial institutions. In the United States, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency charters and regulates all national banks. In some countries, a single entity serves both as the central bank and as the regulatory body for the country’s financial institutions.

In addition, the Basel Accords establish and promote internationally consistent capital requirements and risk management practices for larger international banks. The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, among other functions, has evolved into a standard setter for bank supervision. The various regulations that affect banks present a challenge for bank analysts.

Which of the following statements is most accurate?

A. As a general rule, it is sufficient for an analyst covering an industry to be familiar with financial reporting standards and regulations in his/her country of residence.

B. An analyst should familiarize him/herself with the regulations and reporting standards that affect the company and/or industry that he/she is analyzing.

C. An analyst should be aware that financial reporting standards vary among countries and may be industry specific, but standards are so similar that the analyst does not have to be concerned about it.

Solution: B is correct. An analyst should familiarize him/herself with the regulations and reporting standards that affect the company and/or industry being analyzed. This can be quite challenging but, given the potential effects, necessary.

This section provides a brief overview of the International Accounting Standards Board and the U.S. Financial Accounting Standards Board. The overview is followed by descriptions of the International Organization of Securities Commissions, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, and capital markets regulation in the European Union. The topics covered in these overviews were chosen to serve as examples of standard-setting boards, securities commissions, and capital market regulation. After reading these descriptions, the reader should be able to describe the functioning and roles of standard-setting bodies and regulatory authorities in more detail than is given in the introduction to this section.

3.1. Accounting Standards Boards

Accounting standards boards exist in virtually every national market. These boards are typically independent, private, not-for-profit organizations. Most users of financial statements know of the International Accounting Standard Board that issues international financial reporting standards and the U.S. Financial Accounting Standards Board that is the source of U.S. generally accepted accounting principles. Most countries have an accounting standard-setting body. There are certain attributes that are typically common to these standard setters. After discussing the IASB and the FASB, some of the common and desirable attributes of accounting standards boards will be identified.

3.1.1. International Accounting Standards Board

The IASB is the independent standard-setting body of the IFRS Foundation,5 an independent, not-for-profit private sector organization. The Trustees of the IFRS Foundation reflect a diversity of geographical and professional backgrounds. The Trustees appoint the members of the IASB and related entities, ensure the financing of the Foundation, establish the budget, and monitor the IASB’s strategy and effectiveness. The Trustees of the Foundation are accountable to a monitoring board composed of public authorities that include representatives from the European Commission, IOSCO, the Japan Financial Services Agency, and the U.S. SEC. The chairman of the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision serves as an observer on the Monitoring Board.

The Trustees of the IFRS Foundation make a commitment to act in the public interest. The principle objectives of the IFRS Foundation are to develop and promote the use and adoption of a single set of high quality financial standards; to ensure the standards result in transparent, comparable, and decision-useful information while taking into account the needs of a range of sizes and types of entities in diverse economic settings; and to promote the convergence of national accounting standards and IFRS. The Trustees are responsible for ensuring that the IASB is and is perceived as independent. Each member of the IASB is expected to exercise independence of judgment in setting standards.

The members of the IASB are appointed by the Trustees on the basis of professional competence and practical experience. As is true for the Trustees, the members reflect a diversity of geographical and professional backgrounds. The members deliberate, develop, and issue international financial reporting standards.6 Two related entities, with members appointed by the Trustees, are the IFRS Interpretations Committee and the IFRS Advisory Council.7 The Interpretations Committee’s members are responsible for reviewing accounting issues that arise in the application of IFRS and are not specifically addressed by IFRS, and for issuing appropriate, authoritative, IASB-approved interpretations. Note that the authoritative interpretations must be approved by the IASB. The IFRS Advisory Council’s members represent a wide range of organizations and individuals that are affected by and interested in international financial reporting. The Council provides advice to the IASB on, among other items, agenda decisions and priorities.

The IASB has a basic process that it goes through when deliberating, developing, and issuing international financial reporting standards. A simplified version of the typical process is as follows. An issue is identified as a priority for consideration and placed on the IASB’s agenda in consultation with the Advisory Council. After considering an issue, which may include soliciting advice from others including national standard-setters, the IASB may publish an exposure draft for public comment. In addition to soliciting public comment, the IASB may hold public hearings to discuss proposed standards. After reviewing the input of others, the IASB may issue a new or revised financial reporting standard. These standards are authoritative to the extent that they are recognized and adopted by regulatory authorities.

3.1.2. Financial Accounting Standards Board

The FASB and its predecessor organizations have been issuing financial reporting standards in the United States since the 1930s. The FASB operates within a structure similar to that of the IASB. The Financial Accounting Foundation oversees, administers, and finances the organization. The Foundation ensures the independence of the standard-setting process and appoints members to the FASB and related entities including the Financial Accounting Standards Advisory Council.

The FASB issues new and revised standards to improve standards of financial reporting so that decision-useful information is provided to users of financial reports. This is done through a thorough and independent process that seeks input from stakeholders and is overseen by the Financial Accounting Foundation. The steps in the process are similar to those described for the IASB. The outputs of the standard setting process are contained in the FASB Accounting Standards CodificationTM (Codification).8 Effective for periods ending after 15 September 2009, the Codification is the source of authoritative U.S. generally accepted accounting principles to be applied to nongovernmental entities. The Codification is organized by topic. Among the specific motivations for the Codification, the FASB mentions that it will facilitate researching accounting issues, improve the usability of the literature, provide accurate updated information on an ongoing basis, and help with convergence efforts.

U.S. GAAP, as established by the FASB, is officially recognized as authoritative by the SEC (Financial Reporting Release No. 1, Section 101, and reaffirmed in the April 2003 Policy Statement). However, the SEC retains the authority to establish standards. Although it has rarely overruled the FASB, the SEC does issue authoritative financial reporting guidance including Staff Accounting Bulletins. These bulletins reflect the SEC’s views regarding accounting-related disclosure practices and can be found on the SEC website. Certain portions—but not all portions—of the SEC regulations, releases, interpretations, and guidance are included for reference in the FASB Codification.

3.1.3. Desirable Attributes of Accounting Standards Boards

The responsibilities of all parties involved in the standards setting process—including trustees of a foundation or others that oversee, administer, and finance the organization and members of the standards-setting board—should be clearly defined. All parties involved in the standards-setting process should observe high professional standards, including standards of ethics and confidentiality. The organization should have adequate authority, resources, and competencies to fulfill its responsibilities. The processes that guide the organization and the formation of standards should be clear and consistent. The accounting standards board should be guided by a well-articulated framework with a clearly stated objective. The accounting standards board should operate independently, seeking and considering input from stakeholders but making decisions that are consistent with the stated objective of the framework. The decision setting process should not be compromised by pressure from external forces and should not be influenced by self- or special interests. The decisions and resulting standards should be in the public interest, and culminate in a set of high quality standards that will be recognized and adopted by regulatory authorities.

3.2 Regulatory Authorities

The requirement to prepare financial reports in accordance with specified accounting standards is the responsibility of regulatory authorities. Regulatory authorities are governmental entities that have the legal authority to enforce financial reporting requirements and exert other controls over entities that participate in the capital markets within their jurisdiction. Regulatory authorities may require that financial reports be prepared in accordance with one specific set of accounting standards or may specify acceptable accounting standards. For example in Switzerland, as of 2010, companies listed on the main board of the SIX Swiss Stock Exchange had to prepare their financial statements in accordance with either IFRS or U.S. GAAP. Other registrants in Switzerland could use IFRS, U.S. GAAP, or Swiss GAAP FER.

The International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO) is not a regulatory authority but its members regulate a significant portion of the world’s financial capital markets. This organization has established objectives and principles to guide securities and capital market regulation. The U.S. SEC is discussed as an example of a regulatory authority. Aspects of capital market regulation in Europe are discussed to illustrate a co-operative approach to regulation.

3.2.1. International Organization of Securities Commissions

IOSCO was formed in 1983 as the successor organization to an inter-American regional association (created in 1974). As of 23 September 2010, IOSCO had 114 ordinary members, 11 associate members, and 74 affiliate members. Ordinary members are the securities commission or similar governmental regulatory authority with primary responsibility for securities regulation in the country.9 The members regulate more than 90 percent of the world’s financial capital markets.

The IOSCO’s comprehensive set of Objectives and Principles of Securities Regulation is updated as required and is recognized as an international benchmark for all markets. The principles of securities regulation are based upon three core objectives:10

1. Protecting investors.

2. Ensuring that markets are fair, efficient, and transparent.

3. Reducing systematic risk.

IOSCO’s principles are grouped into nine categories, including principles for regulators, for enforcement, for auditing, and for issuers, among others. Within the category “Principles for Issuers,” two principles relate directly to financial reporting:

1. There should be full, accurate, and timely disclosure of financial results, risk, and other information which is material to investors’ decisions.

2. Accounting standards used by issuers to prepare financial statements should be of a high and internationally acceptable quality.

Historically, regulation and related financial reporting standards were developed within individual countries and were often based on the cultural, economic, and political norms of each country. As financial markets have become more global, it has become desirable to establish comparable financial reporting standards internationally. Ultimately, laws and regulations are established by individual jurisdictions, so this also requires cooperation among regulators. Another IOSCO principle deals with the use of self-regulatory organizations (accounting standards bodies are examples of self-regulating organizations in this context). Principle 9 states:

Where the regulatory system makes use of Self-Regulatory Organizations (SROs) that exercise some direct oversight responsibility for their respective areas of competence, such SROs should be subject to the oversight of the Regulator and should observe standards of fairness and confidentiality when exercising powers and delegated responsibilities.11

To ensure consistent application of international financial standards (such as the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision’s standards and IFRS), it is important to have uniform regulation and enforcement across national boundaries. IOSCO assists in attaining this goal of uniform regulation as well as cross-border co-operation in combating violations of securities and derivatives laws.

3.2.2. The Securities and Exchange Commission (U.S.)

The U.S. SEC has primary responsibility for securities and capital markets regulation in the United States and is an ordinary member of IOSCO. Any company issuing securities within the United States, or otherwise involved in U.S. capital markets, is subject to the rules and regulations of the SEC. The SEC, one of the oldest and most developed regulatory authorities, originated as a result of reform efforts made after the great stock market crash of 1929, sometimes referred to as simply the “Great Crash.”

A number of laws affect reporting companies, broker/dealers, and other market participants. From a financial reporting and analysis perspective, the most significant pieces of legislation are the Securities Acts of 1933 and 1934 and the Sarbanes–Oxley Act of 2002.

- Securities Act of 1933 (The 1933 Act): This act specifies the financial and other significant information that investors must receive when securities are sold, prohibits misrepresentations, and requires initial registration of all public issuances of securities.

- Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (The 1934 Act): This act created the SEC, gave the SEC authority over all aspects of the securities industry, and empowered the SEC to require periodic reporting by companies with publicly traded securities.

- Sarbanes–Oxley Act of 2002: The Sarbanes–Oxley Act of 2002 created the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) to oversee auditors. The SEC is responsible for carrying out the requirements of the act and overseeing the PCAOB. The act addresses auditor independence; for example, it prohibits auditors from providing certain nonaudit services to the companies they audit. The act strengthens corporate responsibility for financial reports; for example, it requires the chief executive officer and the chief financial officer to certify that the company’s financial reports fairly present the company’s condition. Furthermore, Section 404 of the Sarbanes–Oxley Act requires management to report on the effectiveness of the company’s internal control over financial reporting and to obtain a report from its external auditor attesting to management’s assertion about the effectiveness of the company’s internal control.

Companies comply with these acts principally through the completion and submission (i.e., filing) of standardized forms issued by the SEC. There are more than 50 different types of SEC forms that are used to satisfy reporting requirements; the discussion herein will be limited to those forms most relevant for financial analysts.

In 1993, the SEC began to mandate electronic filings of the required forms through its Electronic Data Gathering, Analysis, and Retrieval (EDGAR) system. As of 2005, most SEC filings are required to be made electronically. EDGAR has made corporate and financial information more readily available to investors and the financial community. Most of the SEC filings that an analyst would be interested in can be retrieved from the Internet from one of many websites, including the SEC’s own website. Some filings are required on the initial offering of securities, whereas others are required on a periodic basis thereafter. The following are some of the more common information sources used by analysts.

- Securities Offerings Registration Statement: The 1933 Act requires companies offering securities to file a registration statement. New issuers as well as previously registered companies that are issuing new securities are required to file these statements. Required information and the precise form vary depending upon the size and nature of the offering. Typically, required information includes: (1) disclosures about the securities being offered for sale, (2) the relationship of these new securities to the issuer’s other capital securities, (3) the information typically provided in the annual filings, (4) recent audited financial statements, and (5) risk factors involved in the business.

- Forms 10-K, 20-F, and 40-F: These are forms that companies are required to file annually. Form 10-K is for U.S. registrants, Form 40-F is for certain Canadian registrants, and Form 20-F is for all other non-U.S. registrants. These forms require a comprehensive overview, including information concerning a company’s business, financial disclosures, legal proceedings, and information related to management. The financial disclosures include a historical summary of financial data (usually 10 years), management’s discussion and analysis (MD&A) of the company’s financial condition and results of operations, and audited financial statements.12

- Annual Report: In addition to the SEC’s annual filings (e.g., Form 10-K), most companies prepare an annual report to shareholders. This is not a requirement of the SEC. The annual report is usually viewed as one of the most significant opportunities for a company to present itself to shareholders and other external parties; accordingly, it is often a highly polished marketing document with photographs, an opening letter from the chief executive officer, financial data, market segment information, research and development activities, and future corporate goals. In contrast, the Form 10-K is a more legal type of document with minimal marketing emphasis. Although the perspectives vary, there is considerable overlap between a company’s annual report and its Form 10-K. Some companies elect to prepare just the Form 10-K or a document that integrates both the 10-K and annual report.

- Proxy Statement/Form DEF-14A: The SEC requires that shareholders of a company receive a proxy statement prior to a shareholder meeting. A proxy is an authorization from the shareholder giving another party the right to cast its vote. Shareholder meetings are held at least once a year, but any special meetings also require a proxy statement. Proxies, especially annual meeting proxies, contain information that is often useful to financial analysts. Such information typically includes proposals that require a shareholder vote, details of security ownership by management and principal owners, biographical information on directors, and disclosure of executive compensation. Proxy statement information is filed with the SEC as Form DEF-14A.

- Forms 10-Q and 6-K: These are forms that companies are required to submit for interim periods (quarterly for U.S. companies on Form 10-Q, semiannually for many non-U.S. companies on Form 6-K). The filing requires certain financial information, including unaudited financial statements and a MD&A for the interim period covered by the report. Additionally, if certain types of nonrecurring events—such as the adoption of a significant accounting policy, commencement of significant litigation, or a material limitation on the rights of any holders of any class of registered securities—take place during the period covered by the report, these events must be included in the Form 10-Q report. Companies may provide the 10-Q report to shareholders or may prepare a separate, abbreviated, quarterly report to shareholders.

EXAMPLE 3-3 Initial Registration Statement

In 2004, Google filed a Form S-1 registration statement with the U.S. SEC to register its initial public offering of securities (Class A Common Stock). In addition to a large amount of financial and business information, the registration statement provided a 20-page discussion of risks related to Google’s business and industry. This type of qualitative information is helpful, if not essential, in making an assessment of a company’s credit or investment risk.

Which of the following is least likely to have been included in Google’s registration statement?

A. Audited financial statements.

B. Assessment of risk factors involved in the business.

C. Projected cash flows and earnings for the business.

Solution: C is correct. Companies provide information useful in developing these projections but do not typically include these in the registration statement. Information provided includes audited financial statements, an assessment of risk factors involved in the business, names of the underwriters, estimated proceeds from the offering, and use of proceeds.

A company or its officers make other SEC filings—either periodically, or, if significant events or transactions have occurred, in between the periodic reports noted previously. By their nature, these forms sometimes contain the most interesting and timely information and may have significant valuation implications.

- Form 8-K: In addition to filing annual and interim reports, SEC registrants must report material corporate events on a more current basis. Form 8-K (6-K for non-U.S. registrants) is the “current report” companies must file with the SEC to announce such major events as acquisitions or disposals of corporate assets, changes in securities and trading markets, matters related to accountants and financial statements, corporate governance and management changes, and Regulation FD disclosures.13

- Form 144: This form must be filed with the SEC as notice of the proposed sale of restricted securities or securities held by an affiliate of the issuer in reliance on Rule 144. Rule 144 permits limited sales of restricted securities without registration.

- Forms 3, 4, and 5: These forms are required to report beneficial ownership of securities. These filings are required for any director or officer of a registered company as well as beneficial owners of greater than 10 percent of a class of registered equity securities. Form 3 is the initial statement, Form 4 reports changes, and Form 5 is the annual report. These forms, along with Form 144, can be used to examine purchases and sales of securities by officers, directors, and other affiliates of the company.

- Form 11-K: This is the annual report of employee stock purchase, savings, and similar plans. It might be of interest to analysts for companies with significant employee benefit plans because it contains more information than that disclosed in the company’s financial statements.

In jurisdictions other than the United States, similar legislation exists for the purpose of regulating securities and capital markets. Regulatory authorities are responsible for enforcing regulation, and securities regulation is intended to be consistent with the IOSCO objectives described in the previous section. Within each jurisdiction, regulators will either establish or, more typically, recognize and adopt a specified set or sets of accounting standards. The regulators will also establish reporting and filing requirements. IOSCO members have agreed to cooperate in the development, implementation, and enforcement of internationally recognized and consistent standards of regulation.

3.2.3. Capital Markets Regulation in Europe

Each individual member state of the European Union (EU) regulates capital markets in its jurisdiction. There are, however, certain regulations that have been adopted at the EU level. Importantly, in 2002 the EU agreed that from 1 January 2005, consolidated accounts of EU listed companies would use International Financial Reporting Standards. The endorsement process by which newly issued IFRS are adopted by the EU reflects the balance between the individual member state’s autonomy and the need for cooperation and convergence. When the IASB issues a new standard, the European Financial Reporting Advisory Group advises the European Commission on the standard, and the Standards Advice Review Group provides the Commission an opinion about that advice. Based on the input from these two entities, the Commission prepares a draft endorsement regulation. The Accounting Regulatory Committee votes on the proposal; and if the vote is favorable, the proposal proceeds to the European Parliament and the Council of the European Union for approval.14

Two committees related to securities regulation, established in 2001 by the European Commission, are the European Securities Committee (ESC) and the Committee of European Securities Regulators (CESR). The ESC consists of high-level representatives of member states and advises the European Commission on securities policy issues. The CESR, an independent advisory body composed of representatives of regulatory authorities of the member states, assists the commission, particularly with technical issues. As noted earlier, regulation still rests with the individual member states and, therefore, requirements for registering shares and filing periodic financial reports vary from country to country.

On 1 January 2011, CESR was replaced by the European Securities and Market Authority (ESMA) as part of a reform of the EU financial supervisory framework. The EU Parliament created ESMA as an EU cross-border supervisor because the CESR’s powers were deemed insufficient to co-ordinate supervision of the EU market. ESMA is one of three European supervisory authorities; the two others supervise the banking and insurance industries.

4. CONVERGENCE OF GLOBAL FINANCIAL REPORTING STANDARDS

Recent activities have moved the goal of one set of universally accepted financial reporting standards out of the theoretical sphere and closer to reality. IFRS have been or are in the process of being adopted in many countries. Other countries maintain their own set of standards but are working with the IASB to converge their standards and IFRS.

In some ways, the movement toward one global set of financial reporting standards has made the challenges related to full convergence or adoption of a single set of global standards more apparent. Standard-setting bodies and regulators can have differing views or use a different framework for developing standards. This can be the result of differences in institutional, regulatory, business, and cultural environments. In addition, there may be resistance to change or advocacy for change from certain constituents; accounting boards may be influenced by strong industry lobbying groups and others that will be subject to these reporting standards. For example, the FASB faced strong opposition when it first attempted to adopt standards requiring companies to expense employee stock compensation plans.15 The IASB has experienced similar political pressures. The issue of political pressure is compounded when international standards are involved, simply because there are many more interested parties and many more divergent views and objectives. In the financial crisis of 2008 and 2009, both the FASB and the IASB faced political pressure to amend the standards related to financial instrument accounting. Political pressure and its influence create tension as the independence of accounting standards boards are questioned and jeopardized.

The integrity of the financial reporting framework depends on the standard setter’s ability to invite and balance various points of view and yet to remain independent of external pressures. For analysts, it is important to be aware of the pace of change in accounting standards and factors potentially influencing those changes.

An additional issue related to convergence involves the application and enforcement of accounting standards. Unless the standards are applied consistently and enforcement is uniform, a single set of standards may only appear to exist but desirable attributes such as comparability may be lacking.

In 2002, the IASB and FASB each acknowledged their commitment to the development of high quality, compatible accounting standards that could be used for both domestic and cross-border financial reporting (in an agreement referred to as “the Norwalk Agreement”). Both the IASB and FASB pledged to use their best efforts to (1) make their existing financial reporting standards fully compatible as soon as practicable, and (2) to coordinate their future work programs to ensure that, once achieved, compatibility is maintained. The Norwalk Agreement was certainly an important milestone, and both bodies began working toward convergence. In 2004, the IASB and FASB agreed that, in principle, any significant accounting standard would be developed cooperatively. In 2006, the IASB and the FASB issued another memorandum of understanding (titled “A Roadmap for Convergence between IFRSs and U.S. GAAP”) in which the two Boards identified major projects. They agreed to align their conceptual frameworks; in the short term, to remove selected differences; and in the medium term, to issue joint standards where significant improvements were identified as being required. The joint projects include (but are not limited to): the Conceptual Framework, Fair Value Measurement, Consolidations, Financial Instruments, Financial Statement Presentation, Insurance Contracts, Leases, Post Employment Benefits, and Revenue Recognition. In 2009, the IASB and FASB again reaffirmed their commitment to achieving convergence and affirmed June 2011 as the target completion date for the major projects that had been identified. In mid-2010, however, the Boards acknowledged that all the new standard-setting activity required to achieve that targeted completion would not give stakeholders enough time to provide high quality input in the process. Therefore, the Boards pushed back the target date for some projects to later in 2011.

Meanwhile, as convergence between IFRS and U.S. GAAP continued, the SEC began certain steps regarding the possible adoption of IFRS in the United States. Effective in 2008, the SEC adopted rules to eliminate the reconciliation requirement for foreign private issuers’ financial statements prepared in accordance with IFRS as issued by the IASB. Previously, any non-U.S. issuer using accounting standards other than U.S. GAAP was required to provide a reconciliation to U.S. GAAP. In November 2008, the SEC issued a proposed rule concerning a “Roadmap” for the use of financial statements prepared in accordance with IFRS by U.S. issuers; however the rule did not become final. In February 2010, the SEC issued a “Statement in Support of Convergence and Global Accounting Standards” in which it reiterated its commitment to global accounting standards and directed its staff to execute a work plan to enable the “Commission in 2011 to make a determination regarding incorporating IFRS into the financial reporting system for U.S. issuers.”16

Convergence between IFRS and other local GAAP also continues. For example, convergence between IFRS and Japanese GAAP is underway. In 2008, the IASB and the Accounting Standards Board of Japan published a memorandum of understanding (the “Tokyo Agreement”) outlining work to achieve convergence by June 2011. In 2009, the Japanese Business Accounting Council, a key advisory body to the Commissioner of the Japanese Financial Services Agency, approved a roadmap for the adoption of IFRS in Japan.17

Exhibit 3-1 provides a summary of the adoption status of IFRS in selected worldwide locations. As can be seen, adoption ranges from total adoption of IFRS to requiring local GAAP. Between these two extremes, countries demonstrate different levels of commitment to IFRS including adoption of a local version of IFRS, requirement for certain entities to use IFRS, permission to use IFRS, and use of local GAAP that is converging with IFRS.

EXHIBIT 3-1 International Adoption Status of IFRS in Selected Locations as of June 2010

| Europe |

|

| North America |

|

| Central and South America |

|

| Asia and Middle East |

|

| Oceana |

|

| Africa |

|

Sources: Based on data from www.iasb.org, www.sec.gov, www.iasplus.com, and www.pwc.com.

5. THE INTERNATIONAL FINANCIAL REPORTING STANDARDS FRAMEWORK

The Conceptual Framework for Financial Reporting 2010 sets forth “the concepts that underlie the preparation and presentation of financial statements for external users.” The Conceptual Framework (2010) is designed to assist standard setters in developing and reviewing standards, to assist preparers of financial statements in applying standards and in dealing with issues not specifically covered by standards, to assist auditors in forming an opinion on financial statements, and to assist users in interpreting financial statement information. It is important to note that an understanding of the Conceptual Framework (2010) is expected to assist users of financial statements—including financial analysts—in interpreting the information contained therein.

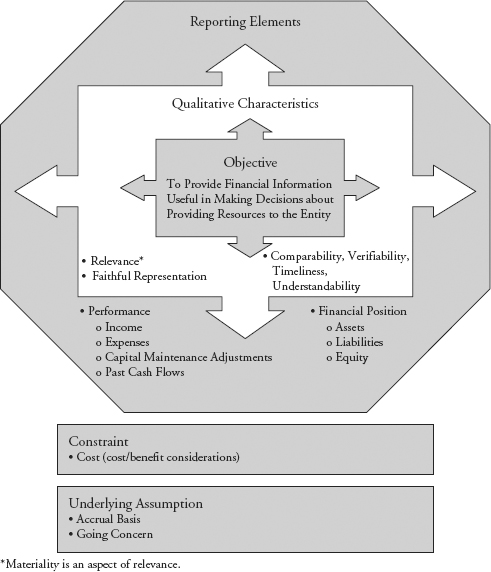

The Conceptual Framework (2010) is diagrammed in Exhibit 3-2. The top part of the diagram shows the objective of general purpose financial reporting at the center, because other aspects of the framework are based upon this core. The qualitative characteristics of useful financial information surround the objective (fundamental characteristics are listed on the left and enhancing characteristics are listed on the right). The reporting elements are shown next with elements of financial statements shown at the bottom. Beneath the diagram of the framework are the basic constraint (cost) and assumption (going concern) that guide the development of standards and the preparation of financial reports.

In the following, we discuss the Conceptual Framework (2010) starting at the core: The objective of financial statements.

5.1. Objective of Financial Reports

At the core of the Conceptual Framework (2010) is the objective: The provision of financial information that is useful to current and potential providers of resources in making decisions. All other aspects of the framework flow from that central objective.

The providers of resources are considered to be the primary users of financial reports and include investors, lenders, and other creditors. The purpose of providing the financial information is to be useful in making decisions about providing resources. Other users may find the financial information useful for making economic decisions. The types of economic decisions differ by users, so the specific information needed differs as well. However, although these users may have unique information needs, some information needs are common across all users. Information is needed about the company’s financial position: its resources and its financial obligations. Information is needed about a company’s financial performance; this information explains how and why the company’s financial position changed in the past and can be useful in evaluating potential changes in the future. The third common information need reflected in the Conceptual Framework (2010) diagram is the need for information about a company’s cash. How did the company obtain cash (by selling its products and services, borrowing, other)? How did the company use cash (by paying expenses, investing in new equipment, paying dividends, other)?

EXHIBIT 3-2 IFRS Framework for the Preparation and Presentation of Financial Reports

The Conceptual Framework (2010) indicates that to make decisions about providing resources to the company, users need information that is helpful in assessing future net cash inflows to the entity. Such information includes information about the economic resources of (assets) and claims against (liabilities and equity) the entity, and about how well the management and governing board have utilized the resources of the entity. It is specifically noted in the Conceptual Framework (2010) that users need to consider information from other sources as well in making their decisions. Further, it is noted that the financial reports do not show the value of an entity but are useful in estimating the value of an entity.

5.2. Qualitative Characteristics of Financial Reports

Flowing from the central objective of providing information that is useful to providers of resources, the Conceptual Framework (2010) elaborates on what constitutes usefulness. It identifies two fundamental qualitative characteristics that make financial information useful: relevance and faithful representation.18 The concept of materiality is discussed within the context of relevance.

1. Relevance: Information is relevant if it would potentially affect or make a difference in users’ decisions. The information can have predictive value (useful in making forecasts), confirmatory value (useful to evaluate past decisions or forecasts), or both. In other words, relevant information helps users of financial information to evaluate past, present, and future events, or to confirm or correct their past evaluations in a decision-making context.

Materiality: Information is considered to be material if omission or misstatement of the information could influence users’ decisions. Materiality is a function of the nature and/or magnitude of the information.

2. Faithful representation: Information that faithfully represents an economic phenomenon that it purports to represent is ideally complete, neutral, and free from error. Complete means that all information necessary to understand the phenomenon is depicted. Neutral means that information is selected and presented without bias. In other words, the information is not presented in such a manner as to bias the users’ decisions. Free from error means that there are no errors of commission or omission in the description of the economic phenomenon, and that an appropriate process to arrive at the reported information was selected and was adhered to without error. Faithful representation maximizes the qualities of complete, neutral, and free from error to the extent possible.

Relevance and faithful representation are the fundamental, most critical characteristics of useful financial information. In addition to these two fundamental characteristics, the Conceptual Framework (2010) identifies four characteristics that enhance the usefulness of relevant and faithfully represented financial information. These enhancing qualitative characteristics are comparability, verifiability, timeliness, and understandability.19

1. Comparability: Comparability allows users “to identify and understand similarities and differences of items.” Information presented in a consistent manner over time and across entities enables users to make comparisons more easily than information with variations in how similar economic phenomena are represented.

2. Verifiability: Verifiability means that different knowledgeable and independent observers would agree that the information presented faithfully represents the economic phenomena it purports to represent.

3. Timeliness: Timely information is available to decision makers prior to their making a decision.

4. Understandability: Clear and concise presentation of information enhances understandability. The Conceptual Framework (2010) specifies that the information is prepared for and should be understandable by users who have a reasonable knowledge of business and economic activities, and who are willing to study the information with diligence. However, some complex economic phenomena cannot be presented in an easily understandable form. Information that is useful should not be excluded simply because it is difficult to understand. It may be necessary for users to seek assistance to understand information about complex economic phenomena.

Financial information exhibiting these qualitative characteristics—fundamental and enhancing—should be useful for making economic decisions.

5.3. Constraints on Financial Reports

Although it would be ideal for financial statements to exhibit all of these qualitative characteristics and thus achieve maximum usefulness, it may be necessary to make tradeoffs across the enhancing characteristics. The application of the enhancing characteristics follows no set order of priority. Depending on the circumstances, each enhancing characteristic may take priority over the others.20 The aim is an appropriate balance among the enhancing characteristics.

A pervasive constraint on useful financial reporting is the cost of providing and using this information.21 Optimally, benefits derived from information should exceed the costs of providing and using it. Again, the aim is a balance between costs and benefits.

A limitation of financial reporting not specifically mentioned in the Conceptual Framework (2010) involves information not included. Financial statements, by necessity, omit information that is nonquantifiable. For example, the creativity, innovation, and competence of a company’s work force are not directly captured in the financial statements. Similarly, customer loyalty, a positive corporate culture, environmental responsibility, and many other aspects about a company may not be directly reflected in the financial statements. Of course, to the extent that these items result in superior financial performance, a company’s financial reports will reflect the results.

EXAMPLE 3-4 Balancing Qualitative Characteristics of Useful Information

A tradeoff between enhancing qualitative characteristics often occurs. For example, when a company records sales revenue, it is required to simultaneously estimate and record an expense for potential bad debts (uncollectible accounts). Including this estimated expense is considered to represent the economic event faithfully and to provide relevant information about the net profits for the accounting period. The information is timely and understandable; but because bad debts may not be known with certainty until a later period, inclusion of this estimated expense involves a sacrifice of verifiability. The bad debt expense is simply an estimate. It is apparent that it is not always possible to simultaneously fulfill all qualitative characteristics.

Companies are most likely to make tradeoffs between which of the following when preparing financial reports?

A. Relevance and materiality.

B. Timeliness and verifiability.

C. Relevance and faithful representation.

Solution: B is correct. Providing timely information implies a shorter time frame between the economic event and the information preparation; however, fully verifying information may require a longer time frame. Relevance and faithful representation are fundamental qualitative characteristics that make financial information useful. Both characteristics are required; there is no tradeoff between these. Materiality is an aspect of relevance.

5.4. The Elements of Financial Statements

Financial statements portray the financial effects of transactions and other events by grouping them into broad classes (elements) according to their economic characteristics.22 Three elements of financial statements are directly related to the measurement of financial position: assets, liabilities, and equity.23

1. Assets: Resources controlled by the enterprise as a result of past events and from which future economic benefits are expected to flow to the enterprise. Assets are what a company owns (e.g., inventory and equipment).

2. Liabilities: Present obligations of an enterprise arising from past events, the settlement of which is expected to result in an outflow of resources embodying economic benefits. Liabilities are what a company owes (e.g., bank borrowings).

3. Equity (for public companies, also known as “shareholders’ equity” or “stockholders’ equity”): Assets less liabilities. Equity is the residual interest in the assets after subtracting the liabilities.

The elements of financial statements directly related to the measurement of performance (profit and related measures) are income and expenses.24

- Income: Increases in economic benefits in the form of inflows or enhancements of assets, or decreases of liabilities that result in an increase in equity (other than increases resulting from contributions by owners). Income includes both revenues and gains. Revenues represent income from the ordinary activities of the enterprise (e.g., the sale of products). Gains may result from ordinary activities or other activities (the sale of surplus equipment).

- Expenses: Decreases in economic benefits in the form of outflows or depletions of assets, or increases in liabilities that result in decreases in equity (other than decreases because of distributions to owners). Expenses include losses, as well as those items normally thought of as expenses, such as the cost of goods sold or wages.

5.4.1. Underlying Assumptions in Financial Statements

Two important assumptions underlie financial statements: accrual accounting and going concern. These assumptions determine how financial statement elements are recognized and measured.25

The use of “accrual accounting” assumes that financial statements should reflect transactions in the period when they actually occur, not necessarily when cash movements occur. For example, accrual accounting specifies that a company reports revenues when they are earned (when the performance obligations have been satisfied), regardless of whether the company received cash before delivering the product, after delivering the product, or at the time of delivery.

“Going concern” refers to the assumption that the company will continue in business for the foreseeable future. To illustrate, consider the value of a company’s inventory if it is assumed that the inventory can be sold over a normal period of time versus the value of that same inventory if it is assumed that the inventory must all be sold in a day (or a week). Companies with the intent to liquidate or materially curtail operations would require different information for a fair presentation.

In reporting the financial position of a company that is assumed to be a going concern, it may be appropriate to list assets at some measure of a current value based upon normal market conditions. However, if a company is expected to cease operations and be liquidated, it may be more appropriate to list such assets at an appropriate liquidation value, namely, a value that would be obtained in a forced sale.

5.4.2. Recognition of Financial Statement Elements

Recognition means that an item is included in the balance sheet or income statement. Recognition occurs if the item meets the definition of an element and satisfies the criteria for recognition. A financial statement element (assets, liabilities, equity, income, and expenses) should be recognized in the financial statements if26

- It is probable that any future economic benefit associated with the item will flow to or from the enterprise.

- The item has a cost or value that can be measured with reliability.

5.4.3. Measurement of Financial Statement Elements

Measurement is the process of determining the monetary amounts at which the elements of the financial statements are to be recognized and carried in the balance sheet and income statement. The following alternative bases of measurement are used to different degrees and in varying combinations to measure assets and liabilities:27

- Historical cost: Historical cost is simply the amount of cash or cash equivalents paid to purchase an asset, including any costs of acquisition and/or preparation. If the asset was not bought for cash, historical cost is the fair value of whatever was given in order to buy the asset. When referring to liabilities, the historical cost basis of measurement means the amount of proceeds received in exchange for the obligation.

- Amortized cost: Historical cost adjusted for amortization, depreciation, or depletion and/or impairment.

- Current cost: In reference to assets, current cost is the amount of cash or cash equivalents that would have to be paid to buy the same or an equivalent asset today. In reference to liabilities, the current cost basis of measurement means the undiscounted amount of cash or cash equivalents that would be required to settle the obligation today.

- Realizable (settlement) value: In reference to assets, realizable value is the amount of cash or cash equivalents that could currently be obtained by selling the asset in an orderly disposal. For liabilities, the equivalent to realizable value is called “settlement value”—that is, settlement value is the undiscounted amount of cash or cash equivalents expected to be paid to satisfy the liabilities in the normal course of business.

- Present value: For assets, present value is the present discounted value of the future net cash inflows that the asset is expected to generate in the normal course of business. For liabilities, present value is the present discounted value of the future net cash outflows that are expected to be required to settle the liabilities in the normal course of business.

- Fair value is a measure of value mentioned but not specifically defined in the Conceptual Framework (2010). Fair value is the amount at which an asset could be exchanged, or a liability settled, between knowledgeable, willing parties in an arm’s length transaction. This may involve either market measures or present value measures depending on the availability of information.28

5.5. General Requirements for Financial Statements

The Conceptual Framework (2010) provides a basis for establishing standards and the elements of financial statements, but it does not address the contents of the financial statements. Having discussed the Conceptual Framework (2010), we now address the general requirements for financial statements.

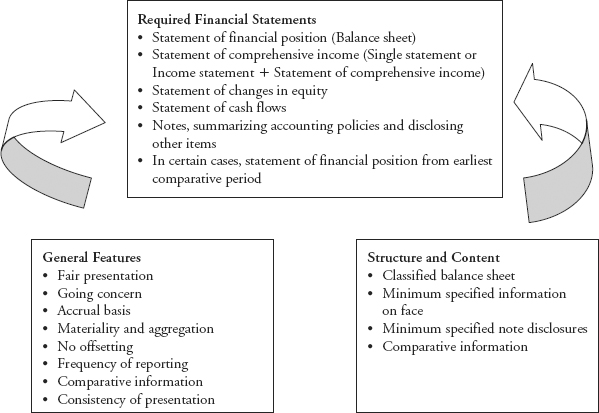

International Accounting Standard (IAS) No. 1, Presentation of Financial Statements, specifies the required financial statements, general features of financial statements, and structure and content of financial statements.29 These general requirements are illustrated in Exhibit 3-3 and described in the following subsections.

In the following sections, we discuss the required financial statements, the general features underlying the preparation of financial statements, and the specified structure and content in greater detail.

EXHIBIT 3-3 IASB General Requirements for Financial Statements

5.5.1. Required Financial Statements

Under IAS No. 1, a complete set of financial statements includes30

- A statement of financial position (balance sheet).

- A statement of comprehensive income (a single statement of comprehensive income or two statements, an income statement and a statement of comprehensive income that begins with profit or loss from the income statement).

- A statement of changes in equity, separately showing changes in equity resulting from profit or loss, each item of other comprehensive income, and transactions with owners in their capacity as owners.31

- A statement of cash flows.

- Notes comprising a summary of significant accounting policies and other explanatory notes that disclose information required by IFRS and not presented elsewhere and that provide information relevant to an understanding of the financial statements.

Entities are encouraged to furnish other related financial and nonfinancial information in addition to that required. Financial statements need to present fairly the financial position, financial performance, and cash flows of an entity.

5.5.2. General Features of Financial Statements

A company that applies IFRS is required to state explicitly in the notes to its financial statements that it is in compliance with the standards. Such a statement is only made when a company is in compliance with all requirements of IFRS. In extremely rare circumstances, a company may deviate from a requirement of IFRS if management concludes that complying with IFRS would result in misleading financial statements. In this case, management must disclose details of the departure from IFRS.

IAS No. 1 specifies a number of general features underlying the preparation of financial statements. These features clearly reflect the Conceptual Framework (2010).

- Fair Presentation: The application of IFRS is presumed to result in financial statements that achieve a fair presentation. The IAS describes fair presentation as follows:

Fair presentation requires the faithful representation of the effects of transactions, other events and conditions in accordance with the definitions and recognition criteria for assets, liabilities, income and expenses set out in the Framework.32

- Going Concern: Financial statements are prepared on a going concern basis unless management either intends to liquidate the entity or to cease trading, or has no realistic alternative but to do so. If not presented on a going concern basis, the fact and rationale should be disclosed.

- Accrual Basis: Financial statements (except for cash flow information) are to be prepared using the accrual basis of accounting.

- Materiality and Aggregation: Omissions or misstatements of items are material if they could, individually or collectively, influence the economic decisions that users make on the basis of the financial statements. Each material class of similar items is presented separately. Dissimilar items are presented separately unless they are immaterial.

- No Offsetting: Assets and liabilities, and income and expenses, are not offset unless required or permitted by an IFRS.

- Frequency of reporting: Financial statements must be prepared at least annually.

- Comparative information: Financial statements must include comparative information from the previous period. The comparative information of prior periods is disclosed for all amounts reported in the financial statements, unless an IFRS requires or permits otherwise.

- Consistency: The presentation and classification of items in the financial statements are usually retained from one period to the next.

5.5.3. Structure and Content Requirements

IAS No. 1 also specifies structure and content of financial statements. These requirements include the following:

- Classified Statement of Financial Position (Balance Sheet): IAS No. 1 requires the balance sheet to distinguish between current and noncurrent assets, and between current and noncurrent liabilities unless a presentation based on liquidity provides more relevant and reliable information (e.g., in the case of a bank or similar financial institution).

- Minimum Information on the Face of the Financial Statements: IAS No. 1 specifies the minimum line item disclosures on the face of, or in the notes to, the financial statements. For example, companies are specifically required to disclose the amount of their plant, property, and equipment as a line item on the face of the balance sheet. The specific requirements are listed in Exhibit 3-4.

- Minimum Information in the Notes (or on the face of financial statements): IAS No. 1 specifies disclosures about information to be presented in the financial statements. This information must be provided in a systematic manner and cross-referenced from the face of the financial statements to the notes. The required information is summarized in Exhibit 3-5.

- Comparative Information: For all amounts reported in a financial statement, comparative information should be provided for the previous period unless another standard requires or permits otherwise. Such comparative information allows users to better understand reported amounts.

EXHIBIT 3-4 IAS No. 1: Minimum Required Line Items in Financial Statements

| On the face of the Statement of Financial Position |

|

| On the face of the Statement of Comprehensive Income, presented either in a single statement or in two statements (Income statement + Statement of comprehensive income) |

|

| On the face of the Statement of Changes in Equity |

|

EXHIBIT 3-5 Summary of IFRS Required Disclosures in the Notes to the Financial Statements

| Disclosure of Accounting Policies |

|

| Sources of Estimation Uncertainty |

|

| Other Disclosures |

|

5.6. Convergence of Conceptual Framework

One of the joint IASB/FASB projects, begun in 2004, aims to develop an improved, common conceptual framework. The project will be conducted in phases. The Boards’ initial, technical work plan included: Objective of and qualitative characteristics of financial reporting; Reporting entity; Elements; and Measurement and recognition of elements. As of the writing of this chapter, the objective and qualitative characteristics phase was complete and is incorporated in the chapter.

As more countries adopt IFRS, the need to consider other financial reporting systems will be reduced. Additionally, the IASB and FASB are considering frameworks from other jurisdictions in developing their joint framework. Nevertheless, analysts are likely to encounter financial statements that are prepared on a basis other than IFRS. Although the number and relevance of different local GAAP reporting systems are likely to decline, industry-specific financial reports—such as those required for banking or insurance companies—will continue to exist. Differences remain between IFRS and U.S. GAAP that affect the framework and general financial reporting requirements. The chapters on individual financial statements and specific topics will review in more detail differences in IFRS and U.S. GAAP as they apply to specific financial statements and topics.

As mentioned earlier, a joint IASB–FASB project was begun in October 2004 to develop a common conceptual framework. The initial focus was to achieve the convergence of the frameworks and improve particular aspects of the framework dealing with objectives, qualitative characteristics, elements and their recognition, and measurement. A December 2004 discussion paper presented the broad differences between the two frameworks. The differences between IFRS and U.S. GAAP that affect the framework and general financial reporting requirements have been reduced by the agreement by the IASB and FASB on the purpose and scope of the Conceptual Framework (2010), the objective of general purpose financial reporting, and qualitative characteristics of useful financial information. Exhibit 3-6 summarizes the remaining differences as presented in the December 2004 discussion paper. Some of the differences identified in December 2004 may no longer apply. The chapters on individual financial statements and specific topics will discuss relevant and more current differences in greater detail.

EXHIBIT 3-6 Summary of Differences between IFRS and U.S. GAAP Frameworks

| U.S. GAAP (FASB) Framework | |

| Financial Statement Elements (definition, recognition, and measurement) |

|

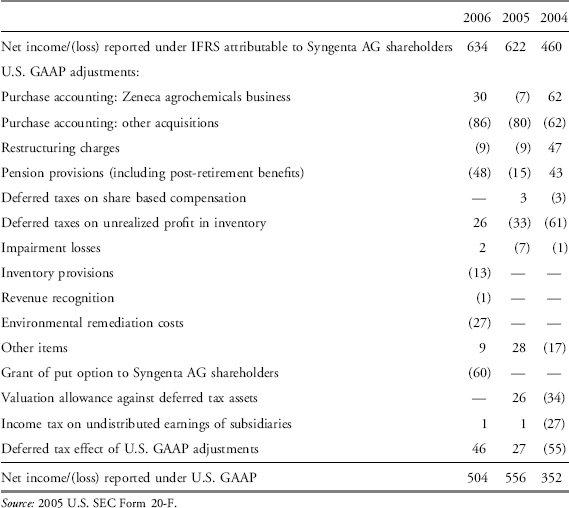

For analysis of financial statements created under different frameworks, reconciliation schedules and disclosures regarding the significant differences between the reporting bases were formerly available to a greater extent. For example, the SEC used to require reconciliation for foreign private issuers that did not prepare financial statements in accordance with U.S. GAAP. The SEC no longer requires reconciliation for foreign private issuers that prepare their financial reports in compliance with IFRS. Such reconciliations can reveal additional information related to the more judgmental components of the financial statements. In the absence of a reconciliation, users of financial statements must be prepared to consider how the use of different reporting standards potentially impact financial reports. This can have important implications for comparing the performance of companies and security valuation.

6. EFFECTIVE FINANCIAL REPORTING

A discussion of the characteristics of an effective framework and the barriers to the creation of such a framework offer additional perspective on financial reporting.

6.1. Characteristics of an Effective Financial Reporting Framework

Any effective financial reporting system needs to be a coherent one (i.e., a framework in which all the pieces fit together according to an underlying logic). Such frameworks have several characteristics:

- Transparency: A framework should enhance the transparency of a company’s financial statements. Transparency means that users should be able to see the underlying economics of the business reflected clearly in the company’s financial statements. Full disclosure and fair presentation create transparency.

- Comprehensiveness: To be comprehensive, a framework should encompass the full spectrum of transactions that have financial consequences. This spectrum includes not only transactions currently occurring, but also new types of transactions as they are developed. So an effective financial reporting framework is based on principles that are universal enough to provide guidance for recording both existing and newly developed transactions.

- Consistency: An effective framework should ensure reasonable consistency across companies and time periods. In other words, similar transactions should be measured and presented in a similar manner regardless of industry, company size, geography, or other characteristics. Balanced against this need for consistency, however, is the need for sufficient flexibility to allow companies sufficient discretion to report results in accordance with underlying economic activity.

6.2. Barriers to a Single Coherent Framework

Although effective frameworks all share the characteristics of transparency, comprehensiveness, and consistency, there are some conflicts that create inherent limitations in any financial reporting standards framework. Specifically, it is difficult to completely satisfy all these characteristics concurrently, so any framework represents an attempt to balance the relative importance of these characteristics. Three areas of conflict include valuation, standard-setting approach, and measurement.

- Valuation: As discussed, various bases for measuring the value of assets and liabilities exist, such as historical cost, current cost, fair value, realizable value, and present value. Historical cost valuation, under which an asset’s value is its initial cost, requires minimal judgment. In contrast, other valuation approaches, such as fair value, require considerable judgment but can provide more relevant information.

- Standard-Setting Approach: Financial reporting standards can be established based on (1) principles, (2) rules, or (3) a combination of principles and rules (sometimes referred to as “objectives oriented”). A principles-based approach provides a broad financial reporting framework with little specific guidance on how to report a particular element or transaction. Such principles-based approaches require the preparers of financial reports and auditors to exercise considerable judgment in financial reporting. In contrast, a rules-based approach establishes specific rules for each element or transaction. Rules-based approaches are characterized by a list of yes-or-no rules, specific numerical tests for classifying certain transactions (known as “bright line tests”), exceptions, and alternative treatments. Some suggest that rules are created in response to preparers’ needs for specific guidance in implementing principles, so even standards that begin purely as principles evolve into a combination of principles and rules. The third alternative, an objectives-oriented approach, combines the other two approaches by including both a framework of principles and appropriate levels of implementation guidance. The common conceptual framework is likely to be more objectives oriented.