CHAPTER 4

UNDERSTANDING INCOME STATEMENTS

After completing this chapter, you will be able to do the following:

- Describe the components of the income statement and alternative presentation formats of that statement.

- Describe the general principles of revenue recognition and accrual accounting, specific revenue recognition applications (including accounting for long-term contracts, installment sales, barter transactions, gross and net reporting of revenue), and the implications of revenue recognition principles for financial analysis.

- Calculate revenue given information that might influence the choice of revenue recognition method.

- Describe the general principles of expense recognition, specific expense recognition applications, and the implications of expense recognition choices for financial analysis.

- Describe the financial reporting treatment and analysis of nonrecurring items (including discontinued operations, extraordinary items, unusual or infrequent items) and changes in accounting standards.

- Distinguish between the operating and nonoperating components of the income statement.

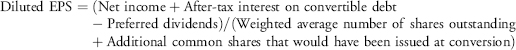

- Describe how earnings per share is calculated and calculate and interpret a company’s earnings per share (both basic and diluted earnings per share) for both simple and complex capital structures.

- Distinguish between dilutive and antidilutive securities, and describe the implications of each for the earnings per share calculation.

- Convert income statements to common-size income statements.

- Evaluate a company’s financial performance using common-size income statements and financial ratios based on the income statement.

- Describe, calculate, and interpret comprehensive income.

- Describe other comprehensive income, and identify the major types of items included in it.

The income statement presents information on the financial results of a company’s business activities over a period of time. The income statement communicates how much revenue the company generated during a period and what costs it incurred in connection with generating that revenue. The basic equation underlying the income statement, ignoring gains and losses, is Revenue minus Expenses equals Net income. The income statement is also sometimes referred to as the “statement of operations,”“statement of earnings,” or “profit and loss (P&L) statement.” Under International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS), the income statement may be presented as a separate statement followed by a statement of comprehensive income that begins with the profit or loss from the income statement or as a section of a single statement of comprehensive income.1 Under U.S. generally accepted accounting principles (U.S. GAAP), the income statement may be presented as a separate statement or as a section of a single statement of income and comprehensive income.2 This chapter focuses on the income statement, but also discusses comprehensive income (profit or loss from the income statement plus other comprehensive income).

Investment analysts intensely scrutinize companies’ income statements.3 Equity analysts are interested in them because equity markets often reward relatively high- or low-earnings growth companies with above-average or below-average valuations, respectively, and because inputs into valuation models often include estimates of earnings. Fixed-income analysts examine the components of income statements, past and projected, for information on companies’ abilities to make promised payments on their debt over the course of the business cycle. Corporate financial announcements frequently emphasize information reported in income statements, particularly earnings, more than information reported in the other financial statements.

This chapter is organized as follows: Section 2 describes the components of the income statement and its format. Section 3 describes basic principles and selected applications related to the recognition of revenue, and Section 4 describes basic principles and selected applications related to the recognition of expenses. Section 5 covers nonrecurring items and nonoperating items. Section 6 explains the calculation of earnings per share. Section 7 introduces income statement analysis, and Section 8 explains comprehensive income and its reporting. A summary of the key points and practice problems in the CFA Institute multiple-choice format complete the chapter.

2. COMPONENTS AND FORMAT OF THE INCOME STATEMENT

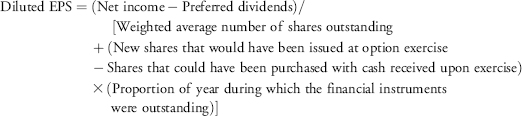

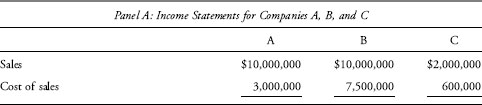

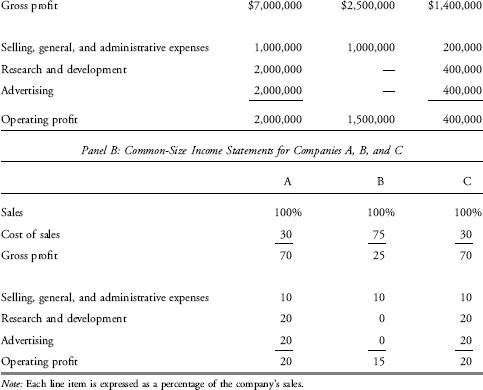

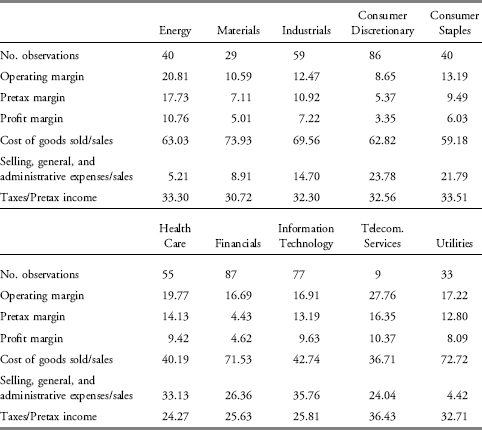

On the top line of the income statement, companies typically report revenue. Revenue generally refers to amounts charged (and expected to be received) for the delivery of goods or services in the ordinary activities of a business. The term net revenue means that the revenue number is reported after adjustments (e.g., for cash or volume discounts, or for estimated returns). Revenue may be called sales or turnover.4 Exhibits 4-1 and 4-2 show the income statements for Groupe Danone (Euronext Paris: BN), a French food manufacturer, and Kraft Foods (NYSE:KFT), a U.S. food manufacturer.5 For the year ended 31 December 2009, Danone reports €14.98 billion of net revenue, whereas Kraft reports $40.39 billion of net revenue.

EXHIBIT 4-1 Groupe Danone Consolidated Income Statement (in millions of euros)

| Year Ended 31 December | ||

| 2008 | 2009 | |

| Net revenue | 15,220 | 14,982 |

| Cost of goods sold | (7,172) | (6,749) |

| Selling expenses | (4,197) | (4,212) |

| General and administrative expenses | (1,297) | (1,356) |

| Research and development expenses | (198) | (206) |

| Other revenue (expense) | (86) | (165) |

| Trading operating income | 2,270 | 2,294 |

| Other operating income (expense) | (83) | 217 |

| Operating income | 2,187 | 2,511 |

| Interest revenue | 58 | 76 |

| Interest expense | (497) | (340) |

| Cost of net debt | (439) | (264) |

| Other financial revenue (expense) | (145) | (225) |

| Income before tax | 1,603 | 2,022 |

| Income tax | (443) | (424) |

| Income from fully consolidated companies | 1,160 | 1,598 |

| Share of profits of associates | 62 | (77) |

| Net income from continuing operations | 1,222 | 1,521 |

| Net income from discontinued operations | 269 | — |

| NET INCOME | 1,491 | 1,521 |

| Attributable to the Group | 1,313 | 1,361 |

| Attributable to minority interests | 178 | 160 |

EXHIBIT 4-2 Kraft Foods and Subsidiaries Consolidated Statements of Earnings (in millions of dollars, except per-share data)

Note that Danone lists the years in increasing order from left to right with the most recent year in the right-most column, whereas Kraft lists the years in decreasing order with the most recent year listed in the left-most column. Different orderings of chronological information are common. Differences in presentations of items, such as expenses, are also common. Expenses reflect outflows, depletions of assets, and incurrences of liabilities in the course of the activities of a business. Expenses may be grouped and reported in different formats, subject to some specific requirements. For example, Danone reports research and development expenses as a separate line item whereas Kraft combines research costs with marketing and administration costs and reports the total in a single line item.

Another difference is how the companies indicate that an amount on the income statement results in a reduction in net income. Danone shows expenses, such as cost of goods sold and selling expenses, in parentheses to explicitly indicate that these are subtracted from revenue and reduce net income. Kraft, on the other hand, does not place cost of sales in parentheses. Rather, Kraft assumes that the user implicitly understands that this is an expense and is subtracted in arriving at gross profit, subtotals such as operating earnings, and, ultimately, innet income. In general, companies may or may not enclose an amount in parentheses (or use a negative sign) to indicate that it is a reduction in net income. Furthermore, within a list of items that normally reduce net income, an item that increases net income may be shown as a negative. In this case, the item is actually added rather than subtracted in calculating net income. In summary, because there is flexibility in how companies may present the income statement, the analyst should always verify the order of years, how expenses are grouped and reported, and how to treat items presented as negatives.

At the bottom of the income statement, companies report net income (companies may use other terms such as “net earnings” or “profit or loss”). For 2009, Danone reports €1,521 million of net income and Kraft reports $3,028 million of net earnings. Net income is often referred to as the “bottom line.” The basis for this expression is that net income is the final—or bottom—line item in an income statement. Because net income is often viewed as the single most relevant number to describe a company’s performance over a period of time, the term “bottom line” sometimes is used in business to refer to any final or most relevant result.

Despite this customary terminology, note that the companies both present another item below net income: information about how much of that net income is attributable to the company itself and how much of that income is attributable to minority interests, or noncontrolling interests. Danone and Kraft both consolidate subsidiaries over which they have control. Consolidation means that they include all of the revenues and expenses of the subsidiaries even if they own less than 100 percent. Minority interest represents the portion of income that “belongs” to minority shareholders of the consolidated subsidiaries, as opposed to the parent company itself. For Danone, €1,361 million of the net income amount is attributable to shareholders of Groupe Danone and €160 million is attributable to minority interests. For Kraft, $3,021 million of the net earnings amount is attributable to the shareholders of Kraft Foods and $7 million is attributable to the noncontrolling interest.

Net income also includes gains and losses, which are increases and decreases in economic benefits, respectively, which may or may not arise in the ordinary activities of the business. For example, when a manufacturing company sells its products, these transactions are reported as revenue, and the costs incurred to generate these revenues are expenses and are presented separately. However, if a manufacturing company sells surplus land that is not needed, the transaction is reported as a gain or a loss. The amount of the gain or loss is the difference between the carrying value of the land and the price at which the land is sold. For example, in Exhibit 4-2, Kraft reports a loss (proceeds, net of carrying value) of $6 million on divestitures in fiscal 2009. Kraft discloses in the notes to consolidated financial statements that the assets sold included a nutritional energy bar operation in the United States, a juice operation in Brazil, and a plant in Spain.

The definition of income encompasses both revenue and gains and the definition of expenses encompasses both expenses that arise in the ordinary activities of the business and losses.6 Thus, net income (profit or loss) can be defined as: (a) income minus expenses, or equivalently (b) revenue plus other income plus gains minus expenses, or equivalently (c) revenue plus other income plus gains minus expenses in the ordinary activities of the business minus other expenses, and minus losses. The last definition can be rearranged as follows: net income equals (i) revenue minus expenses in the ordinary activities of the business, plus (ii) other income minus other expenses, plus (iii) gains minus losses.

In addition to presenting the net income, income statements also present items, including subtotals, that are significant to users of financial statements. Some of the items are specified by IFRS but other items are not specified.7 Certain items, such as revenue, finance costs, and tax expense, are required to be presented separately on the face of the income statement. IFRS additionally require that line items, headings, and subtotals relevant to understanding the entity’s financial performance should be presented even if not specified. Expenses may be grouped together either by their nature or function. Grouping together expenses such as depreciation on manufacturing equipment and depreciation on administrative facilities into a single line item called “depreciation” is an example of a grouping by nature of the expense. An example of grouping by function would be grouping together expenses into a category such as cost of goods sold, which may include labor and material costs, depreciation, some salaries (e.g., salespeople’s), and other direct sales-related expenses.8 Both Danone and Kraft present their expenses by function, which is sometimes referred to “cost of sales” method.

One subtotal often shown in an income statement is gross profit or gross margin (that is revenue less cost of sales). When an income statement shows a gross profit subtotal, it is said to use a multistep format rather than a single-step format. The Kraft Foods income statement is an example of the multistep format, whereas the Groupe Danone income statement is in a single-step format. For manufacturing and merchandising companies, gross profit is a relevant item and is calculated as revenue minus the cost of the goods that were sold. For service companies, gross profit is calculated as revenue minus the cost of services that were provided. In summary, gross profit is the amount of revenue available after subtracting the costs of delivering goods or services. Other expenses related to running the business are subtracted after gross profit.

Another important subtotal which may be shown on the income statement is operating profit (or, synonymously, operating income). Operating profit results from deducting operating expenses such as selling, general, administrative, and research and development expenses from gross profit. Operating profit reflects a company’s profits on its usual business activities before deducting taxes, and for nonfinancial companies, before deducting interest expense. For financial companies, interest expense would be included in operating expenses and subtracted in arriving at operating profit because it relates to the operating activities for such companies. For some companies composed of a number of separate business segments, operating profit can be useful in evaluating the performance of the individual business segments, because interest and tax expenses may be more relevant at the level of the overall company rather than an individual segment level. The specific calculations of gross profit and operating profit may vary by company, and a reader of financial statements can consult the notes to the statements to identify significant variations across companies.

Operating profit is sometimes referred to as EBIT (earnings before interest and taxes). However, operating profit and EBIT are not necessarily the same. Note that in both Exhibits 4-1 and 4-2, interest and taxes do not represent the only differences between earnings (net income, net earnings) and operating income. For example, both companies separately report some income from discontinued operations.

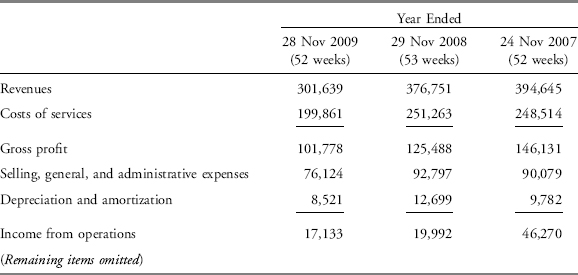

Exhibit 4-3 shows an excerpt from the income statement of CRA International (NASDAQ GS: CRAI), a company providing management consulting services. Accordingly, CRA deducts cost of services (rather than cost of goods) from revenues to derive gross profit. CRA’s fiscal year ends on the last Saturday in November, and periodically (for example in 2008) its fiscal year will contain 53 weeks rather than 52 weeks. Although the extra week is likely immaterial in computing year-to-year growth rates, it may have a material impact on a quarter containing the extra week. In general, an analyst should be alert to the effect of an extra week when making historical comparisons and forecasting future performance.

EXHIBIT 4-3 CRA International Inc. Consolidated Statements of Income (Excerpt) (in thousands of dollars, except per-share data)

Exhibits 4-1, 4-2, and 4-3 illustrate basic points about the income statement, including variations across the statements—some of which depend on the industry and/or country, and some of which reflect differences in accounting policies and practices of a particular company. In addition, some differences within an industry are primarily differences in terminology, whereas others are more fundamental accounting differences. Notes to the financial statements are helpful in identifying such differences.

Having introduced the components and format of an income statement, the next objective is to understand the actual reported numbers in it. To accurately interpret reported numbers, the analyst needs to be familiar with the principles of revenue and expense recognition—that is, how revenue and expenses are measured and attributed to a given accounting reporting period.

Revenue is the top line in an income statement, so we begin the discussion of line items in the income statement with revenue recognition. A first task is to explain some relevant accounting terminology.

The terms revenue, sales, gains, losses, and net income (profit, net earnings) have been briefly defined. The IASB Framework for the Preparation and Presentation of Financial Statements (referred to hereafter as “the Framework”) further defines and discusses these income statement items. The Framework explains that profit is a frequently used measure of performance and is composed of income and expenses.9 It defines income as follows:

Income is increases in economic benefits during the accounting period in the form of inflows or enhancements of assets or decreases of liabilities that result in increases in equity, other than those relating to contributions from equity participants.10

In IFRS, the term “income” includes revenue and gains. Gains are similar to revenue, but they typically arise from secondary or peripheral activities rather than from a company’s primary business activities. For example, for a restaurant, the sale of surplus restaurant equipment for more than its carrying value is referred to as a gain rather than as revenue. Similarly, a loss typically arises from secondary activities. Gains and losses may be considered part of operating activities (e.g., a loss due to a decline in the value of inventory) or may be considered part of nonoperating activities (e.g., the sale of nontrading investments).

In the following simple hypothetical scenario, revenue recognition is straightforward: a company sells goods to a buyer for cash and does not allow returns, so the company recognizes revenue when the exchange of goods for cash takes place and measures revenue at the amount of cash received. In practice, however, determining when revenue should be recognized and at what amount is considerably more complex for reasons discussed in the following sections.

3.1. General Principles

An important aspect concerning revenue recognition is that it can occur independently of cash movements. For example, assume a company sells goods to a buyer on credit, so does not actually receive cash until some later time. A fundamental principle of accrual accounting is that revenue is recognized (reported on the income statement) when it is earned, so the company’s financial records reflect revenue from the sale when the risk and reward of ownership is transferred; this is often when the company delivers the goods or services. If the delivery was on credit, a related asset, such as trade or accounts receivable, is created. Later, when cash changes hands, the company’s financial records simply reflect that cash has been received to settle an account receivable. Similarly, there are situations when a company receives cash in advance and actually delivers the product or service later, perhaps over a period of time. In this case, the company would record a liability for unearned revenue when the cash is initially received, and revenue would be recognized as being earned over time as products and services are delivered. An example would be a subscription payment received for a publication that is to be delivered periodically over time.

When to recognize revenue (when to report revenue on the income statement) is a critical issue in accounting.11 IFRS specify that revenue from the sale of goods is to be recognized (reported on the income statement) when the following conditions are satisfied:12

- The entity has transferred to the buyer the significant risks and rewards of ownership of the goods.

- The entity retains neither continuing managerial involvement to the degree usually associated with ownership nor effective control over the goods sold.

- The amount of revenue can be measured reliably.

- It is probable that the economic benefits associated with the transaction will flow to the entity.

- The costs incurred or to be incurred in respect of the transaction can be measured reliably.

In simple words, this basically says revenue is recognized when the seller no longer bears risks with respect to the goods (for example, if the goods were destroyed by fire, it would be a loss to the purchaser), the seller cannot tell the purchaser what to do with the goods, the seller knows what it expects to collect and is reasonably certain of collection, and the seller knows how much the goods cost.

IFRS note that the transfer of the risks and rewards of ownership normally occurs when goods are delivered to the buyer or when legal title to goods transfers. However, as noted by the earlier remaining conditions, physical transfer of goods will not always result in the recognition of revenue. For example, if goods are delivered to a retail store to be sold on consignment and title is not transferred, the revenue would not yet be recognized.13

IFRS specify similar criteria for recognizing revenue for the rendering of services.14 When the outcome of a transaction involving the rendering of services can be estimated reliably, revenue associated with the transaction shall be recognized by reference to the stage of completion of the transaction at the balance sheet date. The outcome of a transaction can be estimated reliably when all the following conditions are satisfied:

- The amount of revenue can be measured reliably.

- It is probable that the economic benefits associated with the transaction will flow to the entity.

- The stage of completion of the transaction at the balance sheet date can be measured reliably.

- The costs incurred for the transaction and the costs to complete the transaction can be measured reliably.

IFRS criteria for recognizing interest, royalties, and dividends are that it is probable that the economic benefits associated with the transaction will flow to the entity and the amount of the revenue can be reliably measured.

U.S. GAAP15 specify that revenue should be recognized when it is “realized or realizable and earned.” The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC),16 motivated in part because of the frequency with which overstating revenue occurs in connection with fraud and/or misstatements, provides guidance on how to apply the accounting principles. This guidance lists four criteria to determine when revenue is realized or realizable and earned:

1. There is evidence of an arrangement between buyer and seller. For instance, this would disallow the practice of recognizing revenue in a period by delivering the product just before the end of an accounting period and then completing a sales contract after the period end.

2. The product has been delivered, or the service has been rendered. For instance, this would preclude revenue recognition when the product has been shipped but the risks and rewards of ownership have not actually passed to the buyer.

3. The price is determined, or determinable. For instance, this would preclude a company from recognizing revenue that is based on some contingency.

4. The seller is reasonably sure of collecting money. For instance, this would preclude a company from recognizing revenue when the customer is unlikely to pay.

Companies must disclose their revenue recognition policies in the notes to their financial statements (sometimes referred to as footnotes). Analysts should review these policies carefully to understand how and when a company recognizes revenue, which may differ depending on the types of product sold and services rendered. Exhibit 4-4 presents a portion of the summary of significant accounting policies note that discusses revenue recognition for DaimlerChrysler (DB-F: DAI) from its 2009 annual report, prepared under IFRS.

EXHIBIT 4-4 Excerpt from DaimlerChrysler Notes

Revenue from sales of vehicles, service parts and other related products is recognized when the risks and rewards of ownership of the goods are transferred to the customer, the amount of revenue can be estimated reliably and collectability is reasonably assured. Revenue is recognized net of discounts, cash sales incentives, customer bonuses and rebates granted.

Daimler uses price discounts in response to a number of market and product factors, including pricing actions and incentives offered by competitors, the amount of excess industry production capacity, the intensity of market competition and consumer demand for the product. The Group may offer a variety of sales incentive programs at any point in time, including cash offers to dealers and consumers, lease subsidies which reduce the consumers’ monthly lease payment, or reduced financing rate programs offered to consumers.

An analyst comparing Daimler with another company would likely want to ensure that revenue recognition policies are similar. For example, Daimler notes that it recognizes its revenue net of certain items. Does the comparison company deduct the same items from revenue? Exhibit 4-5 presents excerpts from the 2009 annual report’s notes to the financial statements of Ford Motor Company (NYSE:F) prepared under U.S. GAAP. In Ford’s Note 2, Summary of Accounting Policies, the section titled revenue recognition mentions the criteria and timing of revenue recognition, but not the recognition of revenue net of certain items. In a subsequent section of Note 2, Ford states that its marketing incentives are recognized as revenue reductions. A comparison of the disclosed revenue recognition policies suggests that the companies do have similar revenue recognition policies despite minor differences in presentation.

EXHIBIT 4-5 Excerpt from Ford Motor Company Notes

Revenue Recognition—Automotive Sector

Automotive sales consist primarily of revenue generated from the sale of vehicles. Sales are recorded when the risks and rewards of ownership are transferred to our customers (generally dealers and distributors). For the majority of our sales, this occurs when products are shipped from our manufacturing facilities or delivered to our customers. When vehicles are shipped to customers or vehicle modifiers on consignment, revenue is recognized when the vehicle is sold to the ultimate customer.

[portions omitted]

Marketing Incentives and Interest Supplements

Marketing incentives generally are recognized by the Automotive sector as revenue reductions in Automotive sales. These include customer and dealer cash payments and costs for special financing and leasing programs paid to the Financial Services sector. The revenue reductions are accrued at the later of the date the related vehicle sales to the dealers are recorded or the date the incentive program is both approved and communicated. We generally estimate these accruals using marketing programs that are approved as of the balance sheet date and are expected to be effective at the beginning of the subsequent period. The Financial Services sector identifies payments for special financing and leasing programs as interest supplements or other support costs and recognizes them consistent with the earnings process of the underlying receivable or operating lease.

The topic of revenue recognition remains important and new challenges have evolved, particularly in areas of e-commerce and services such as software development. Standard setters continue to evaluate current revenue recognition standards and issue new guidance periodically to deal with new types of transactions. Additionally, there are occasional special cases for revenue recognition, as discussed in the next section.

3.2. Revenue Recognition in Special Cases

The general principles discussed previously are helpful for dealing with most revenue recognition issues. There are some instances where revenue recognition is more difficult to determine. For example, in limited circumstances, revenue may be recognized before or after goods are delivered or services are rendered, as summarized in Exhibit 4-6.

EXHIBIT 4-6 Revenue Recognition in Special Cases

| Before Goods Are Fully Delivered or Services Completely Rendered | At the Time Goods Are Delivered or Services Rendered | After Goods Are Delivered or Services Rendered |

| For example, with long-term contracts where the outcome can be reliably measured, the percentage-of-completion method is used. | Recognize revenues using normal revenue recognition criteria. | For example, with real estate sales where there is doubt about the buyer’s ability to complete payments, the installment method and cost recovery method are appropriate. |

The following sections discuss revenue recognition in the case of long-term contracts, installment sales, and barter.

3.2.1. Long-Term Contracts

A long-term contract is one that spans a number of accounting periods. Such contracts raise issues in determining when the earnings process has been completed and revenue recognition should occur. How should a company apportion the revenue earned under a long-term contract to each accounting period? If, for example, the contract is a service contract or a licensing arrangement, the company may recognize the revenue on a prorated basis over the period of time of the contract rather than at the end of the contract term. Under IFRS, this may be done using the percentage-of-completion method.17 Under the percentage-of-completion method, revenue is recognized based on the stage of completion of a transaction or contract and is, thus, recognized when the services are rendered. Construction contracts are examples of contracts that may span a number of accounting periods and that may use the percentage-of-completion method.18 IFRS provide that when the outcome of a construction contract can be measured reliably, revenue and expenses should be recognized in reference to the stage of completion. U.S. GAAP have similar requirements for long-term contracts including construction contracts.

Under the percentage-of-completion method, in each accounting period, the company estimates what percentage of the contract is complete and then reports that percentage of the total contract revenue in its income statement. Contract costs for the period are expensed against the revenue. Therefore, net income or profit is reported each year as work is performed.

Under IFRS, if the outcome of the contract cannot be measured reliably, then revenue may be recognized to the extent of contract costs incurred (but only if it is probable the costs will be recovered). Costs are expensed in the period incurred. Under this method, no profit is recognized until all the costs had been recovered. Under U.S. GAAP, but not under IFRS, a revenue recognition method used when the outcome cannot be measured reliably is the completed contract method. Under the completed contract method, the company does not report any income until the contract is substantially finished (the remaining costs and potential risks are insignificant in amount), although provision should be made for expected losses. Billings and costs are accumulated on the balance sheet rather than flowing through the income statement. Under U.S. GAAP, the completed contract method is also acceptable when the entity has primarily short-term contracts. Note that if a contract is started and completed in the same period, there is no difference between the percentage-of-completion and completed contract methods.

Examples 4-1, 4-2, and 4-3 provide illustrations of these revenue recognition methods. As shown, the percentage-of-completion method results in revenue recognition sooner than the completed contract method and thus may be considered a less conservative approach. In addition, the percentage-of-completion method relies on management estimates and is thus not as objective as the completed contract method. However, an advantage of the percentage-of-completion method is that it results in better matching of revenue recognition with the accounting period in which it was earned. Because of better matching with the periods in which work is performed, the percentage-of-completion method is the preferred method of revenue recognition for long-term contracts and is required when the outcome can be measured reliably under both IFRS and U.S. GAAP. Under both IFRS and U.S. GAAP, if a loss is expected on the contract, the loss is reported immediately, not upon completion of the contract, regardless of the method used (e.g., percentage-of-completion or completed contract).

EXAMPLE 4-1 Revenue Recognition for Long-Term Contracts: Recognizing Revenue on a Prorated Basis

New Era Network Associates has a five-year license to provide networking support services to a customer. The total amount of the license fee to be received by New Era is $1 million. New Era recognizes license revenue on a prorated basis regardless of the time at which cash is received. How much revenue will New Era recognize for this license in each year?

Solution: For this license, New Era Network Associates will recognize $200,000 each year for five years (calculated as $1 million divided by 5).

EXAMPLE 4-2 Revenue Recognition for Long-Term Contracts: Percentage-of-Completion Method

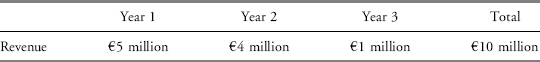

Stelle Technology has a contract to build a network for a customer for a total sales price of €10 million. The network will take an estimated three years to build, and total building costs are estimated to be €6 million. Stelle recognizes long-term contract revenue using the percentage-of-completion method and estimates percentage complete based on expenditure incurred as a percentage of total estimated expenditures.

1. At the end of Year 1, the company had spent €3 million. Total costs to complete are estimated to be another €3 million. How much revenue will Stelle recognize in Year 1?

2. At the end of Year 2, the company had spent an additional €2.4 million for an accumulated total of €5.4 million. Total costs to complete are estimated to be another €0.6 million. How much revenue will Stelle recognize in Year 2?

3. At the end of Year 3, the contract is complete. The company spent an accumulated total of €6 million. How much revenue will Stelle recognize in Year 3?

Solution to 1: Stelle has spent 50 percent of the total project costs (€3 million divided by €6 million), so in Year 1, the company will recognize 50 percent of the total contract revenue (i.e., €5 million).

Solution to 2: Because Stelle has spent 90 percent of the total project costs (€5.4 million divided by €6 million), by the end of Year 2, it will need to have recognized 90 percent of the total contract revenue (i.e., €9 million). Stelle has already recognized €5 million of revenue in Year 1, so in Year 2, the company will recognize €4 million revenue (€9 million minus €5 million).

Solution to 3: Because Stelle has spent 100 percent of the total project costs, by the end of Year 3, it will need to have recognized 100 percent of the total contract revenue (i.e., €10 million). Stelle had already recognized €9 million of revenue by the end of Year 2, so in Year 3, the company will recognize €1 million revenue (€10 million minus €9 million).

EXAMPLE 4-3 Revenue Recognition for Long-Term Contracts: Outcome Cannot Be Reliably Measured

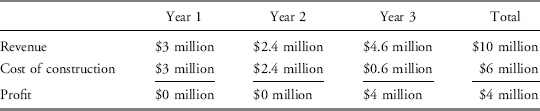

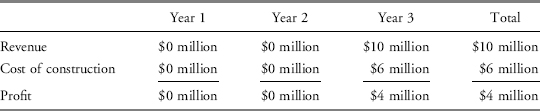

Kolenda Technology Group has a contract to build a network for a customer for a total sales price of $10 million. This network will take an estimated three years to build, but considerable uncertainty surrounds total building costs because new technologies are involved. In other words, the outcome cannot be reliably measured, but it is probable that the costs up to the agreed upon price will be recovered.

Assuming the following expenditures, how much revenue, expense (cost of construction), and income would the company recognize each year under IFRS and using the completed contract method under U.S. GAAP? The amounts periodically billed to the customer and received from the customer are not necessarily equivalent to the amount of revenue being recognized in the period. For simplicity, assume Kolenda pays cash for all expenditures.

1. At the end of Year 1, Kolenda has spent $3 million.

2. At the end of Year 2, Kolenda has spent a total of $5.4 million.

3. At the end of Year 3, the contract is complete. Kolenda spent a total of $6 million.

Solution: Under IFRS, revenue may be recognized to the extent of contract costs incurred if the outcome of the contract cannot be measured reliably and it is probable that costs will be recovered. In this example, the outcome is uncertain but it is probable that Kolenda will recover the costs up to $10 million. Under U.S. GAAP, the company would use the completed contract method. No revenue will be recognized until the contract is complete.

Year 1: Under IFRS, Kolenda would recognize $3 million cost of construction, $3 million revenue, and thus $0 income. Under U.S. GAAP, Kolenda would recognize $0 cost of construction, $0 revenue, and thus $0 income. The $3 million expenditure would be reported as an increase in the inventory account “construction in progress” and a decrease in cash.

Year 2: Under IFRS, Kolenda would recognize $2.4 million cost of construction, $2.4 million revenue, and thus $0 income. Under U.S. GAAP, Kolenda would recognize $0 cost of construction, $0 revenue, and thus $0 income. The $2.4 million expenditures would be reported as an increase in the inventory account “construction in progress” and a decrease in cash.

Year 3: Under IFRS, Kolenda would recognize the $0.6 million cost of construction incurred in the period. Because the contract has been completed and the outcome is now measurable, the company would recognize the remaining $4.6 million revenue on the contract, and thus $4 million income. Under U.S. GAAP, because the contract has been completed, Kolenda would recognize the total contract revenue (i.e., $10 million). Kolenda would recognize $6 million cost of construction and thus $4 million income. The inventory account “construction in progress” would be eliminated.

Summary

Revenue Recognition to the Extent of Contract Costs Incurred: IFRS

Completed Contract Method: U.S. GAAP

3.2.2. Installment Sales

As noted earlier, revenue is normally reported when goods are delivered or services are rendered, independent of the period in which cash payments for those goods or services are received. This principle applies even to installment sales—sales in which proceeds are to be paid in installments over an extended period. For installment sales, IFRS separate the installments into the sale price, which is the discounted present value of the installment payments, and an interest component. Revenue attributable to the sale price is recognized at the date of sale, and revenue attributable to the interest component is recognized over time.19 International standards note, however, that the guidance for revenue recognition must be considered in light of local laws regarding the sale of goods in a particular country. Under limited circumstances, recognition of revenue or profit may be required to be deferred for some installment sales. An example of such deferral arises for certain sales of real estate on an installment basis. Revenue recognition for sales of real estate varies depending on specific aspects of the sale transaction.20

Under U.S. GAAP, when the seller has completed the significant activities in the earnings process and is either assured of collecting the selling price or able to estimate amounts that will not be collected, a sale of real estate is reported at the time of sale using the normal revenue recognition conditions.21 When those two conditions are not fully met, under U.S. GAAP some of the profit is deferred. Two of the methods may be appropriate in these limited circumstances and relate to the amount of profit to be recognized each year from the transaction: the installment method and the cost recovery method. Under the installment method, the portion of the total profit of the sale that is recognized in each period is determined by the percentage of the total sales price for which the seller has received cash. Under the cost recovery method, the seller does not report any profit until the cash amounts paid by the buyer—including principal and interest on any financing from the seller—are greater than all the seller’s costs of the property. Note that the cost recovery method is similar to the revenue recognition method under international standards, described earlier, when the outcome of a contract cannot be measured reliably (although the term cost recovery method is not used in the international standard).

Example 4-4 illustrates the differences between the installment method and the cost recovery method. Installment sales and cost recovery treatment of revenue recognition are rare for financial reporting purposes, especially for assets other than real estate.

EXAMPLE 4-4 The Installment and Cost Recovery Methods of Revenue Recognition

Assume the total sales price and cost of a property are $2,000,000 and $1,100,000, respectively, so that the total profit to be recognized is $900,000. The amount of cash received by the seller as a down payment is $300,000, with the remainder of the sales price to be received over a 10-year period. It has been determined that there is significant doubt about the ability and commitment of the buyer to complete all payments. How much profit will be recognized attributable to the down payment if:

1. the installment method is used?

2. the cost recovery method is used?

Solution to 1: The installment method apportions the cash receipt between cost recovered and profit using the ratio of profit to sales value; here, this ratio equals $900,000/$2,000,000=0.45 or 45 percent. Therefore, the seller will recognize the following profit attributable to the down payment: 45 percent of $300,000=$135,000.

Solution to 2: Under the cost recovery method of revenue recognition, the company would not recognize any profit attributable to the down payment because the cash amounts paid by the buyer still do not exceed the cost of $1,100,000.

3.2.3. Barter

Revenue recognition issues related to barter transactions became particularly important as e-commerce developed. As an example, if Company A exchanges advertising space for computer equipment from Company B but no cash changes hands, can Company A and B both report revenue? Such an exchange is referred to as a “barter transaction.”

An even more challenging revenue recognition issue evolved from a specific type of barter transaction, a round-trip transaction. As an example, if Company A sells advertising services (or energy contracts, or commodities) to Company B and almost simultaneously buys an almost identical product from Company B, can Company A report revenue at the fair value of the product sold? Because the company’s revenue would be approximately equal to its expense, the net effect of the transaction would have no impact on net income or cash flow. However, the amount of revenue reported would be higher, and the amount of revenue can be important to a company’s valuation. In the earlier stages of e-commerce, for example, some equity valuations were based on sales (because many early Internet companies reported no net income).

Under IFRS, revenue from barter transactions must be measured based on the fair value of revenue from similar nonbarter transactions with unrelated parties (parties other than the barter partner).22 U.S. GAAP state that revenue can be recognized at fair value only if a company has historically received cash payments for such services and can thus use this historical experience as a basis for determining fair value; otherwise, the revenue from the barter transaction is recorded at the carrying amount of the asset surrendered.23

3.2.4. Gross versus Net Reporting

Another revenue recognition issue that became particularly important with the emergence of e-commerce is the issue of gross versus net reporting. Merchandising companies typically sell products that they purchased from a supplier. In accounting for their sales, the company records the amount of the sale proceeds as sales revenue and their cost of the products as the cost of goods sold. As Internet-based merchandising companies developed, many sold products that they had never held in inventory; they simply arranged for the supplier to ship the products directly to the end customer. In effect, many such companies were agents of the supplier company, and the net difference between their sales proceeds and their costs was equivalent to a sales commission. What amount should these companies record as their revenues—the gross amount of sales proceeds received from their customers, or the net difference between sales proceeds and their cost?

U.S. GAAP indicate that the approach should be based on the specific situation and provides guidance for determining when revenue should be reported gross versus net.24 To report gross revenues, the following criteria are relevant: the company is the primary obligor under the contract, bears inventory risk and credit risk, can choose its supplier, and has reasonable latitude to establish price. If these criteria are not met, the company should report revenues net. Example 4-5 provides an illustration.

EXAMPLE 4-5 Gross versus Net Reporting of Revenues

Flyalot has agreements with several major airlines to obtain airline tickets at reduced rates. The company pays only for tickets it sells to customers. In the most recent period, Flyalot sold airline tickets to customers over the Internet for a total of $1.1 million. The cost of these tickets to Flyalot was $1 million. The company’s direct selling costs were $2,000. Once the customers receive their ticket, the airline is responsible for providing all services associated with the customers’ flight.

1. Demonstrate the reporting of revenues under:

A. gross reporting.

B. net reporting.

2. Determine and justify the appropriate method for reporting revenues.

Solution to 1: The following table shows how reporting would appear on a gross and a net basis:

| A. Gross Reporting | B. Net Reporting | |

| Revenues | $1,100,000 | $100,000 |

| Cost of sales | 1,002,000 | 2,000 |

| Gross margin | $98,000 | $98,000 |

Solution to 2: Flyalot should report revenue on a net basis. Flyalot pays only for tickets it sells to customers and thus does not bear inventory risk. In addition, the airline—not Flyalot—is the primary obligor under the contract. Revenues should be reported as $100,000.

3.3. Implications for Financial Analysis

As we have seen, companies use a variety of revenue recognition methods. Furthermore, a single company may use different revenue recognition policies for different businesses. Companies disclose their revenue recognition policies in the notes to their financial statement, often in the first note.

The following aspects of a company’s revenue recognition policy are particularly relevant to financial analysis: whether a policy results in recognition of revenue sooner rather than later (sooner is less conservative), and to what extent a policy requires the company to make estimates. In order to analyze a company’s financial statements, and particularly to compare one company’s financial statements with those of another company, it is helpful to understand any differences in their revenue recognition policies. Although it may not be possible to calculate the monetary effect of differences between particular companies’ revenue recognition policies and estimates, it is generally possible to characterize the relative conservatism of a company’s policies and to qualitatively assess how differences in policies might affect financial ratios.

EXAMPLE 4-6 Revenue Recognition Policy for Apple

As disclosed in the excerpt from notes to the consolidated financial statements shown below (emphasis added), Apple Inc. (NasdaqGS: AAPL) uses different revenue recognition policies depending on the type of revenue producing activity, including product sales, service and support contracts, and products obtained from other companies. Note that these are only the first three paragraphs of Apple’s disclosure on revenue recognition; the entire revenue recognition portion has nine paragraphs.

Revenue Recognition

Net sales consist primarily of revenue from the sale of hardware, software, digital content and applications, peripherals, and service and support contracts. The Company recognizes revenue when persuasive evidence of an arrangement exists, delivery has occurred, the sales price is fixed or determinable, and collection is probable. Product is considered delivered to the customer once it has been shipped and title and risk of loss have been transferred. For most of the Company’s product sales, these criteria are met at the time the product is shipped. For online sales to individuals, for some sales to education customers in the U.S., and for certain other sales, the Company defers revenue until the customer receives the product because the Company legally retains a portion of the risk of loss on these sales during transit [portions omitted].

Revenue from service and support contracts is deferred and recognized ratably over the service coverage periods. These contracts typically include extended phone support, repair services, web-based support resources, diagnostic tools, and extend the service coverage offered under the Company’s standard limited warranty.

The Company sells software and peripheral products obtained from other companies. The Company generally establishes its own pricing and retains related inventory risk, is the primary obligor in sales transactions with its customers, and assumes the credit risk for amounts billed to its customers. Accordingly, the Company generally recognizes revenue for the sale of products obtained from other companies based on the gross amount billed.

Source: Apple Inc. 10-K/A for the year ended 26 September 2009, as filed with the SEC on 25 January 2010. Emphasis added.

1. What criteria does Apple apply to determine when to recognize revenue from product sales?

2. What principle underpins the company’s deferral of revenue from service and support contracts?

Solution to 1: Apple recognizes revenue when persuasive evidence of an arrangement exists, delivery has occurred, the sales price is fixed or determinable, and collection is probable. Note that these are just the four U.S. GAAP revenue recognition criteria described in Section 3.1. Note also that Apple recognizes revenue on some product sales at the time of shipment and others at the time of delivery, depending on when its risk of loss ends.

Solution to 2: The basic principle underpinning the company’s deferral of revenue for service and sales contracts is that revenue should be recognized in the period it is earned. Because service under these contracts will be performed in future periods, the company defers the revenue and then recognizes it over the time it is earned.

With familiarity of the basic principles of revenue recognition in hand, the next section begins a discussion of expense recognition.

Expenses are deducted against revenue to arrive at a company’s net profit or loss. Under the IASB Framework, expenses are “decreases in economic benefits during the accounting period in the form of outflows or depletions of assets or incurrences of liabilities that result in decreases in equity, other than those relating to distributions to equity participants.”25

The IASB Framework also states:

The definition of expenses encompasses losses as well as those expenses that arise in the course of the ordinary activities of the enterprise. Expenses that arise in the course of the ordinary activities of the enterprise include, for example, cost of sales, wages and depreciation. They usually take the form of an outflow or depletion of assets such as cash and cash equivalents, inventory, property, plant and equipment.

Losses represent other items that meet the definition of expenses and may, or may not, arise in the course of the ordinary activities of the enterprise. Losses represent decreases in economic benefits and as such they are no different in nature from other expenses. Hence, they are not regarded as a separate element in this Framework.

Losses include, for example, those resulting from disasters such as fire and flood, as well as those arising on the disposal of noncurrent assets.26

Similar to the issues with revenue recognition, in a simple hypothetical scenario, expense recognition would not be an issue. For instance, assume a company purchased inventory for cash and sold the entire inventory in the same period. When the company paid for the inventory, absent indications to the contrary, it is clear that the inventory cost has been incurred and when that inventory is sold, it should be recognized as an expense (cost of goods sold) in the financial records. Assume also that the company paid all operating and administrative expenses in cash within each accounting period. In such a simple hypothetical scenario, no issues of expense recognition would arise. In practice, however, as with revenue recognition, determining when expenses should be recognized can be somewhat more complex.

4.1. General Principles

In general, a company recognizes expenses in the period that it consumes (i.e., uses up) the economic benefits associated with the expenditure, or loses some previously recognized economic benefit.27

A general principle of expense recognition is the matching principle. Strictly speaking, IFRS do not refer to a “matching principle” but rather to a “matching concept” or to a process resulting in “matching of costs with revenues.”28 The distinction is relevant in certain standard-setting deliberations. Under matching, a company recognizes some expenses (e.g., cost of goods sold) when associated revenues are recognized and thus, expenses and revenues are matched. Associated revenues and expenses are those that result directly and jointly from the same transactions or events. Unlike the simple scenario in which a company purchases inventory and sells all of the inventory within the same accounting period, in practice, it is more likely that some of the current period’s sales are made from inventory purchased in a previous period or previous periods. It is also likely that some of the inventory purchased in the current period will remain unsold at the end of the current period and so will be sold in a following period. Matching requires that a company recognizes cost of goods sold in the same period as revenues from the sale of the goods.

Period costs, expenditures that less directly match revenues, are reflected in the period when a company makes the expenditure or incurs the liability to pay. Administrative expenses are an example of period costs. Other expenditures that also less directly match revenues relate more directly to future expected benefits; in this case, the expenditures are allocated systematically with the passage of time. An example is depreciation expense.

Examples 4-7 and 4-8 demonstrate matching applied to inventory and cost of goods sold.

EXAMPLE 4-7 The Matching of Inventory Costs with Revenues

Kahn Distribution Limited (KDL) purchases inventory items for resale. At the beginning of 2009, Kahn had no inventory on hand. During 2009, Kahn had the following transactions:

Inventory Purchases

| First quarter | 2,000 units at $40 per unit |

| Second quarter | 1,500 units at $41 per unit |

| Third quarter | 2,200 units at $43 per unit |

| Fourth quarter | 1,900 units at $45 per unit |

| Total | 7,600 units at a total cost of $321,600 |

KDL sold 5,600 units of inventory during the year at $50 per unit, and received cash. KDL determines that there were 2,000 remaining units of inventory and specifically identifies that 1,900 were those purchased in the fourth quarter and 100 were purchased in the third quarter. What are the revenue and expense associated with these transactions during 2009 based on specific identification of inventory items as sold or remaining in inventory?

Solution: The revenue for 2009 would be $280,000 (5,600 units × $50 per unit). Initially, the total cost of the goods purchased would be recorded as inventory (an asset) in the amount of $321,600. During 2009, the cost of the 5,600 units sold would be expensed (matched against the revenue) while the cost of the 2,000 remaining unsold units would remain in inventory as follows:

Cost of Goods Sold

| From the first quarter | 2,000 units at $40 per unit = $80,000 |

| From the second quarter | 1,500 units at $41 per unit = $61,500 |

| From the third quarter | 2,100 units at $43 per unit = $90,300 |

| Total cost of goods sold | $231,800 |

Cost of Goods Remaining in Inventory

| From the third quarter | 100 units at $43 per unit = $4,300 |

| From the fourth quarter | 1,900 units at $45 per unit = $85,500 |

| Total remaining (or ending) inventory cost | $89,800 |

To confirm that total costs are accounted for: $231,800+$89,800=$321,600. The cost of the goods sold would be expensed against the revenue of $280,000 as follows:

| Revenue | $280,000 |

| Cost of goods sold | 231,800 |

| Gross profit | $48,200 |

An alternative way to think about this is that the company created an asset (inventory) of $321,600 as it made its purchases. At the end of the period, the value of the company’s inventory on hand is $89,800. Therefore, the amount of the Cost of goods sold expense recognized for the period should be the difference: $231,800.

The remaining inventory amount of $89,800 will be matched against revenue in a future year when the inventory items are sold.

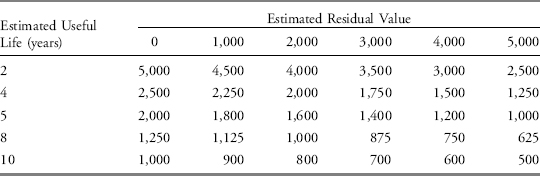

EXAMPLE 4-8 Alternative Inventory Costing Methods

In Example 4-7, KDL was able to specifically identify which inventory items were sold and which remained in inventory to be carried over to later periods. This is called the specific identification method and inventory and cost of goods sold are based on their physical flow. It is generally not feasible to specifically identify which items were sold and which remain on hand, so accounting standards permit the assignment of inventory costs to costs of goods sold and to ending inventory using cost formulas (IFRS terminology) or cost flow assumptions (U.S. GAAP). The cost formula or cost flow assumption determines which goods are assumed to be sold and which goods are assumed to remain in inventory. Both IFRS and U.S. GAAP permit the use of the first in, first out (FIFO) method, and the weighted average cost method to assign costs.

Under the FIFO method, the oldest goods purchased (or manufactured) are assumed to be sold first and the newest goods purchased (or manufactured) are assumed to remain in inventory. Cost of goods in beginning inventory and costs of the first items purchased (or manufactured) flow into cost of goods sold first, as if the earliest items purchased sold first. Ending inventory would, therefore, include the most recent purchases. It turns out that those items specifically identified as sold in Example 7 were also the first items purchased, so in this example, under FIFO, the cost of goods sold would also be $231,800, calculated as previously.

The weighted average cost method assigns the average cost of goods available for sale to the units sold and remaining in inventory. The assignment is based on the average cost per unit (total cost of goods available for sale/total units available for sale) and the number of units sold and the number remaining in inventory.

For KDL, the weighted average cost per unit would be

$321,600/7,600 units=$42.3158 per unit

Cost of goods sold using the weighted average cost method would be

5,600 units at $42.3158=$236,968

Ending inventory using the weighted average cost method would be

2,000 units at $42.3158=$84,632

Another method is permitted under U.S. GAAP but is not permitted under IFRS. This is the last in, first out (LIFO) method. Under the LIFO method, the newest goods purchased (or manufactured) are assumed to be sold first and the oldest goods purchased (or manufactured) are assumed to remain in inventory. Costs of the latest items purchased flow into cost of goods sold first, as if the most recent items purchased were sold first. Although this may seem contrary to common sense, it is logical in certain circumstances. For example, lumber in a lumberyard may be stacked up with the oldest lumber on the bottom. As lumber is sold, it is sold from the top of the stack, so the last lumber purchased and put in inventory is the first lumber out. Theoretically, a company should choose a method linked to the physical inventory flows.29 Under the LIFO method, in the KDL example, it would be assumed that the 2,000 units remaining in ending inventory would have come from the first quarter’s purchases:30

Ending inventory 2,000 units at $40 per unit=$80,000

The remaining costs would be allocated to cost of goods sold under LIFO:

Total costs of $321,600 less $80,000 remaining in ending inventory=$241,600

Alternatively, the cost of the last 5,600 units purchased is allocated to cost of goods sold under LIFO:

1,900 units at $45 per unit+2,200 units at $43 per unit+1,500 units at $41 per unit=$241,600

An alternative way to think about expense recognition is that the company created an asset (inventory) of $321,600 as it made its purchases. At the end of the period, the value of the company’s inventory is $80,000. Therefore, the amount of the Cost of goods sold expense recognized the period should be the difference: $241,600.

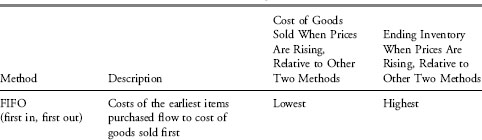

Exhibit 4-7 summarizes and compares inventory costing methods.

EXHIBIT 4-7 Summary Table on Inventory Costing Methods

4.2. Issues in Expense Recognition

The following sections cover applications of the principles of expense recognition to certain common situations.

4.2.1. Doubtful Accounts

When a company sells its products or services on credit, it is likely that some customers will ultimately default on their obligations (i.e., fail to pay). At the time of the sale, it is not known which customer will default. (If it were known that a particular customer would ultimately default, presumably a company would not sell on credit to that customer.) One possible approach to recognizing credit losses on customer receivables would be for the company to wait until such time as a customer defaulted and only then recognize the loss (direct write-off method). Such an approach would usually not be consistent with generally accepted accounting principles.

Under the matching principle, at the time revenue is recognized on a sale, a company is required to record an estimate of how much of the revenue will ultimately be uncollectible. Companies make such estimates based on previous experience with uncollectible accounts. Such estimates may be expressed as a proportion of the overall amount of sales, the overall amount of receivables, or the amount of receivables overdue by a specific amount of time. The company records its estimate of uncollectible amounts as an expense on the income statement, not as a direct reduction of revenues.

4.2.2. Warranties

At times, companies offer warranties on the products they sell. If the product proves deficient in some respect that is covered under the terms of the warranty, the company will incur an expense to repair or replace the product. At the time of sale, the company does not know the amount of future expenses it will incur in connection with its warranties. One possible approach would be for a company to wait until actual expenses are incurred under the warranty and to reflect the expense at that time. However, this would not result in a matching of the expense with the associated revenue.

Under the matching principle, a company is required to estimate the amount of future expenses resulting from its warranties, to recognize an estimated warranty expense in the period of the sale, and to update the expense as indicated by experience over the life of the warranty.

4.2.3. Depreciation and Amortization

Companies commonly incur costs to obtain long-lived assets. Long-lived assets are assets expected to provide economic benefits over a future period of time greater than one year. Examples are land (property), plant, equipment, and intangible assets (assets lacking physical substance) such as trademarks. The costs of most long-lived assets are allocated over the period of time during which they provide economic benefits. The two main types of long-lived assets whose costs are not allocated over time are land and those intangible assets with indefinite useful lives.

Depreciation is the process of systematically allocating costs of long-lived assets over the period during which the assets are expected to provide economic benefits. “Depreciation” is the term commonly applied to this process for physical long-lived assets such as plant and equipment (land is not depreciated), and amortization is the term commonly applied to this process for intangible long-lived assets with a finite useful life.31 Examples of intangible long-lived assets with a finite useful life include an acquired mailing list, an acquired patent with a set expiration date, and an acquired copyright with a set legal life. The term “amortization” is also commonly applied to the systematic allocation of a premium or discount relative to the face value of a fixed-income security over the life of the security.

IFRS allow two alternative models for valuing property, plant, and equipment: the cost model and the revaluation model.32 Under the cost model, the depreciable amount of that asset (cost less residual value) is allocated on a systematic basis over the remaining useful life of the asset. Under the cost model, the asset is reported at its cost less any accumulated depreciation. Under the revaluation model, the asset is reported at its fair value. The revaluation model is not permitted under U.S. GAAP. Here, we will focus only on the cost model. There are two other differences between IFRS and U.S. GAAP to note: IFRS require each component of an asset to be depreciated separately and U.S. GAAP do not require component depreciation; and IFRS require an annual review of residual value and useful life, and U.S. GAAP do not explicitly require such a review.

The method used to compute depreciation should reflect the pattern over which the economic benefits of the asset are expected to be consumed. IFRS do not prescribe a particular method for computing depreciation but note that several methods are commonly used, such as the straight-line method, diminishing balance method (accelerated depreciation), and the units of production method (depreciation varies depending upon production or usage).

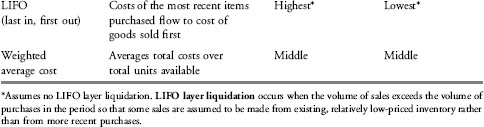

The straight-line method allocates evenly the cost of long-lived assets less estimated residual value over the estimated useful life of an asset. (The term “straight line” derives from the fact that the annual depreciation expense, if represented as a line graph over time, would be a straight line. In addition, a plot of the cost of the asset minus the cumulative amount of annual depreciation expense, if represented as a line graph over time, would be a straight line with a negative downward slope.) Calculating depreciation and amortization requires two significant estimates: the estimated useful life of an asset and the estimated residual value (also known as “salvage value”) of an asset. Under IFRS, the residual value is the amount that the company expects to receive upon sale of the asset at the end of its useful life. Example 4-9 assumes that an item of equipment is depreciated using the straight-line method and illustrates how the annual depreciation expense varies under different estimates of the useful life and estimated residual value of an asset. As shown, annual depreciation expense is sensitive to both the estimated useful life and to the estimated residual value.

EXAMPLE 4-9 Sensitivity of Annual Depreciation Expense to Varying Estimates of Useful Life and Residual Value

Using the straight-line method of depreciation, annual depreciation expense is calculated as:

![]()

Assume the cost of an asset is $10,000. If, for example, the residual value of the asset is estimated to be $0 and its useful life is estimated to be 5 years, the annual depreciation expense under the straight-line method would be ($10,000−$0)/5 years=$2,000. In contrast, holding the estimated useful life of the asset constant at 5 years but increasing the estimated residual value of the asset to $4,000 would result in annual depreciation expense of only $1,200 [calculated as ($10,000−$4,000)/5 years]. Alternatively, holding the estimated residual value at $0 but increasing the estimated useful life of the asset to 10 years would result in annual depreciation expense of only $1,000 [calculated as ($10,000−$0)/10 years]. Exhibit 4-8 shows annual depreciation expense for various combinations of estimated useful life and residual value.

EXHIBIT 4-8 Annual Depreciation Expense (in dollars)

Generally, alternatives to the straight-line method of depreciation are called accelerated methods of depreciation because they accelerate (i.e., speed up) the timing of depreciation. Accelerated depreciation methods allocate a greater proportion of the cost to the early years of an asset’s useful life. These methods are appropriate if the plant or equipment is expected to be used up faster in the early years (e.g., an automobile). A commonly used accelerated method is the diminishing balance method, (also known as the declining balance method). The diminishing balance method is demonstrated in Example 4-10.

EXAMPLE 4-10 An Illustration of Diminishing Balance Depreciation

Assume the cost of computer equipment was $11,000, the estimated residual value is $1,000, and the estimated useful life is five years. Under the diminishing or declining balance method, the first step is to determine the straight-line rate, the rate at which the asset would be depreciated under the straight-line method. This rate is measured as 100 percent divided by the useful life or 20 percent for a five-year useful life. Under the straight-line method, 1/5 or 20 percent of the depreciable cost of the asset (here, $11,000−$1,000=$10,000) would be expensed each year for five years: The depreciation expense would be $2,000 per year.

The next step is to determine an acceleration factor that approximates the pattern of the asset’s wear. Common acceleration factors are 150 percent and 200 percent. The latter is known as double declining balance depreciation because it depreciates the asset at double the straight-line rate. Using the 200 percent acceleration factor, the diminishing balance rate would be 40 percent (20 percent × 2.0). This rate is then applied to the remaining undepreciated balance of the asset each period (known as the net book value).

At the beginning of the first year, the net book value is $11,000. Depreciation expense for the first full year of use of the asset would be 40 percent of $11,000, or $4,400. Under this method, the residual value, if any, is generally not used in the computation of the depreciation each period (the 40 percent is applied to $11,000 rather than to $11,000 minus residual value). However, the company will stop taking depreciation when the salvage value is reached.

At the beginning of Year 2, the net book value is measured as

| Asset cost | $11,000 |

| Less: Accumulated depreciation | (4,400) |

| Net book value | $6,600 |

For the second full year, depreciation expense would be $6,600 × 40 percent, or $2,640. At the end of the second year (i.e., beginning of the third year), a total of $7,040 ($4,400+$2,640) of depreciation would have been recorded. So, the remaining net book value at the beginning of the third year would be

| Asset cost | $11,000 |

| Less: Accumulated depreciation | (7,040) |

| Net book value | $3,960 |

For the third full year, depreciation would be $3,960 × 40 percent, or $1,584. At the end of the third year, a total of $8,624 ($4,400+$2,640+$1,584) of depreciation would have been recorded. So, the remaining net book value at the beginning of the fourth year would be

| Asset cost | $11,000 |

| Less: Accumulated depreciation | (8,624) |

| Net book value | $2,376 |

For the fourth full year, depreciation would be $2,376 × 40 percent, or $950. At the end of the fourth year, a total of $9,574 ($4,400+$2,640+$1,584+$950) of depreciation would have been recorded. So, the remaining net book value at the beginning of the fifth year would be

| Asset cost | $11,000 |

| Less: Accumulated depreciation | (9,574) |

| Net book value | $1,426 |

For the fifth year, if deprecation were determined as in previous years, it would amount to $570 ($1,426 × 40 percent). However, this would result in a remaining net book value of the asset below its estimated residual value of $1,000. So, instead, only $426 would be depreciated, leaving a $1,000 net book value at the end of the fifth year.

| Asset cost | $11,000 |

| Less: Accumulated depreciation | (10,000) |

| Net book value | $1,000 |

Companies often use a zero or small residual value, which creates problems for diminishing balance depreciation because the asset never fully depreciates. In order to fully depreciate the asset over the initially estimated useful life when a zero or small residual value is assumed, companies often adopt a depreciation policy that combines the diminishing balance and straight-line methods. An example would be a deprecation policy of using double-declining balance depreciation and switching to the straight-line method halfway through the useful life.

Under accelerated depreciation methods, there is a higher depreciation expense in early years relative to the straight-line method. This results in higher expenses and lower net income in the early depreciation years. In later years, there is a reversal with accelerated depreciation expense lower than straight-line depreciation. Accelerated depreciation is sometimes referred to as a conservative accounting choice because it results in lower net income in the early years of asset use.

For those intangible assets that must be amortized (those with an identifiable useful life), the process is the same as for depreciation; only the name of the expense is different. IFRS state that if a pattern cannot be determined over the useful life, then the straight-line method should be used.33 In most cases under IFRS and U.S. GAAP, amortizable intangible assets are amortized using the straight-line method with no residual value. Goodwill34 and intangible assets with indefinite life are not amortized. Instead, they are tested at least annually for impairment (i.e., if the current value of an intangible asset or goodwill is materially lower than its value in the company’s books, the value of the asset is considered to be impaired and its value in the company’s books must be decreased).

In summary, to calculate depreciation and amortization, a company must choose a method, estimate the asset’s useful life, and estimate residual value. Clearly, different choices have a differing effect on depreciation or amortization expense and, therefore, on reported net income.

4.3. Implications for Financial Analysis

A company’s estimates for doubtful accounts and/or for warranty expenses can affect its reported net income. Similarly, a company’s choice of depreciation or amortization method, estimates of assets’ useful lives, and estimates of assets’ residual values can affect reported net income. These are only a few of the choices and estimates that affect a company’s reported net income.

As with revenue recognition policies, a company’s choice of expense recognition can be characterized by its relative conservatism. A policy that results in recognition of expenses later rather than sooner is considered less conservative. In addition, many items of expense require the company to make estimates that can significantly affect net income. Analysis of a company’s financial statements, and particularly comparison of one company’s financial statements with those of another, requires an understanding of differences in these estimates and their potential impact.

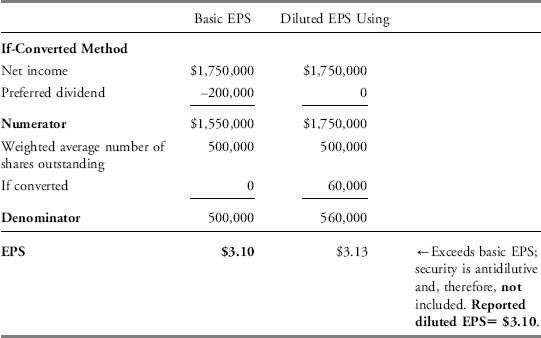

If, for example, a company shows a significant year-to-year change in its estimates of uncollectible accounts as a percentage of sales, warranty expenses as percentage of sales, or estimated useful lives of assets, the analyst should seek to understand the underlying reasons. Do the changes reflect a change in business operations (e.g., lower estimated warranty expenses reflecting recent experience of fewer warranty claims because of improved product quality)? Or are the changes seemingly unrelated to changes in business operations and thus possibly a signal that a company is manipulating estimates in order to achieve a particular effect on its reported net income?