CHAPTER 16

EVALUATING FINANCIAL REPORTING QUALITY

After completing this chapter, you will be able to do the following:

- Contrast cash-basis and accrual-basis accounting, and explain why accounting discretion exists in an accrual accounting system.

- Describe the relation between the level of accruals and the persistence of earnings and the relative multiples that the cash and accrual components of earnings should rationally receive in valuation.

- Explain opportunities and motivations for management to intervene in the external financial reporting process and mechanisms that discipline such intervention.

- Describe earnings quality and measures of earnings quality, and compare the earnings quality of peer companies.

- Explain mean reversion in earnings and how the accruals component of earnings affects the speed of mean reversion.

- Explain potential problems that affect the quality of financial reporting, including revenue recognition, expense recognition, balance sheet issues, and cash flow statement issues, and interpret warning signs of these potential problems.

Financial statement analysis involves taking a systematic approach to using information contained in the financial statements to assist in decision making. The set of decision makers using financial statements is varied. However, one thing they have in common is an interest in assessing a company’s future cash flow generating capability. Equity investors and analysts, credit investors and analysts, rating agencies, customers, employees, tax authorities, and others all have a need to estimate a company’s future cash flows. Although there are many sources of information relevant to such forecasting, one of the principal sources, and our focus in this reading, is the company’s financial statements (inclusive of supplemental information to the main financial statements).

Financial reporting quality relates to the accuracy with which a company’s reported financials reflect its operating performance and to their usefulness for forecasting future cash flows. Our focus in introducing this topic is on the income statement and the discretion (exercise of choice) embedded in the recording of various revenues and expenses—this affects net income, which is simply net revenue less total expense. Simple measures that capture the aggregate discretion reflected in reported net income are a very effective way to measure financial reporting quality. Companies exercising more (less) discretion can usually be classified as having weaker (stronger) financial reporting quality. This separation is especially useful in identifying companies who will have weaker (stronger) future cash flow generating capability.

The discussion in this reading extends the material introduced in the reading on financial statement analysis techniques. We begin with some fundamentals to highlight the extent of discretion that is embedded in financial statements. This discretion is a necessary part of financial reporting, but it brings with it unintended consequences. Discretion necessitates preparers of financial statements to make numerous “estimates” that suffer from neutral errors as well as strategic manipulation. We will walk through many examples of how discretion in the financial reporting system manifests itself in the form of systematic biases, which analysts would be foolhardy to ignore given the ever-increasing role that accounting numbers play in contracts and asset pricing. Our discussion will be broad, and will be generally from the perspective of an equity or credit analyst. However, much of the material covered is also relevant to the corporate financial analyst for evaluating acquisitions, restructurings, and other investments, and for calculating the value generated by strategic scenarios.

The remainder of this reading is organized as follows: Section 2 introduces discretion in accounting systems, comparing accrual and cash bases of accounting. Understanding this basic, yet often subtle, difference is crucial to all of the material in the reading, as it defines the scope for discretion that resides in the financial statements. Section 3 lays out the general context for financial reporting quality and introduces simple measures of financial reporting quality. Section 4 provides a structure for computing, analyzing, and interpreting various indicators and measures of financial reporting and earnings quality. Section 5 briefly discusses the implications for financial reporting quality of the trend towards fair value accounting. A summary of the key points and practice problems in the CFA Institute multiple-choice format conclude the reading.

2. DISCRETION IN ACCOUNTING SYSTEMS

To understand the issues in evaluating the quality of financial reporting, the analyst should be familiar with the context in which managerial discretion in accounting is exercised and with the principles and objectives of accrual accounting. The following sections provide that background.

2.1. Distinguishing Cash Basis from Accrual Basis Accounting

Our focus on external financial statements centers on the three primary financial statements: the balance sheet, income statement, and statement of cash flows. The balance sheet is a snapshot of the various asset, liability, and equity accounts. It reflects the financial status of the entity at a point in time. The income statement reports revenues less expenses, and the statement of cash flows which, when reported using the indirect method (which starts with net income), articulates how the change in cash observed on the balance sheet can reconcile to reported income.

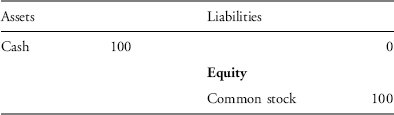

To help put these statements in context and clarify the importance of accrual accounting, consider a bicycle repair shop, Cadence Cycling. At the start of the current year the owner contributes $100 cash into the business. The opening balance sheet would look as follows:

Cadence Cycling Balance Sheet (Cash-Basis Accounting) as of 1 January 2007

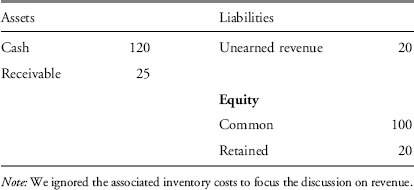

During 2007, Cadence Cycling attracted two customers who brought their bikes to the store for service. The first customer pays $20 up front for the bike service and repairs. The second customer does not pay for the service up front; the estimated price for the service is $25. By the end of 2007, Cadence has completed work for the second customer but has not started the work for the first customer (we are ignoring the associated inventory parts to keep the example simple).

Under pure cash basis accounting, the only relevant transactions for the financial statements are those that involve cash. Thus, the balance sheet needed for this example includes only cash and cash equivalents, and the income statement (and statement of cash flows) is simply the change in cash and cash equivalents not attributable to external capital providers. The income statement and balance sheet under the cash basis would be as follows:

Cadence Cycling Income Statement (Cash-Basis Accounting) for the Year Ended 31 December 2007

| Revenues | |

| Cash collected from Customer #1 | 20 |

| Expenses | 0 |

| Net income | 20 |

Cadence Cycling Balance Sheet (Cash-Basis Accounting) as of 31 December 2007

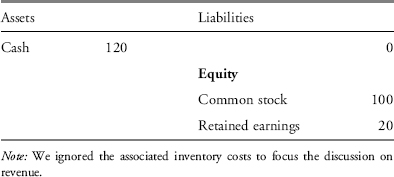

Obviously, we do not see such financial statements in practice for publicly traded companies (although we will see how financial statements can be recast to compute a pure cash basis of earnings, which can be used to benchmark accrued earnings). Instead, we see an accrual accounting system. In contrast to cash basis accounting, under accrual basis of accounting it is not the cash flow that defines when revenues and expenses are recorded in the financial statements; rather, there is an earnings process that triggers the recognition of revenues and expenses. Revenues are increases in net assets that result from the principal income-generating activity of the company, and expenses are reductions in net assets associated with the creation of those revenues. Thus, for example, accrual accounting records revenue not when cash is collected, but when a good or service has been provided to the customer. The income statement and balance sheet under the accrual basis for Cadence Cycling would be as follows:

Cadence Cycling Income Statement (Accrual-Basis Accounting) for the Year Ended 31 December 2007

| Revenues | |

| Bike services for Customer #2 | 25 |

| Expenses | 0 |

| Net income | 25 |

Cadence Cycling Balance Sheet (Accrual-Basis Accounting) as of 31 December 2007

There is a striking difference in the summary performance measure across the two sets of financial statements. Under the cash basis, Cadence Cycling reports return on average total assets (ROA) of $20/[($100+$120)/2] = 18.2%, whereas under the accrual basis the ROA is $25/[($100+$145)/2] = 20.4%. There is good reason to focus on the accrual-based earnings measure of performance, as it gives a better indication of the “true” value-creating activities during the year. The differences between ROA on a cash basis and on an accrual basis of accounting are even greater if we consider investment activities in noncurrent assets (assets that have long useful lives). Under cash basis accounting, if these noncurrent investments, such as the purchase of property, plant, and equipment (PP&E), are paid for with cash, the cash outflow would constitute a reduction to income in the year of the investment, whereas under the accrual basis of accounting that amount initially gets capitalized as an asset and is then periodically depreciated over the useful life of the asset. In the year of the investment, an ROA measure from the cash basis will be substantially lower than under the accrual basis. Conversely, in later periods, if the company makes fewer such investments in PP&E, then ROA will be higher under the cash basis in those future periods as the depreciation charge will continue to flow through the income statement under the accrual basis of accounting. This example naturally leads to the question: What are the relative merits of cash basis and accrual earnings?

One of the main objectives of external financial statements is to provide information that is useful to investors. Accrual accounting has emerged as the accepted method of achieving this objective. Accrual accounting centers on the identification and measurement of assets and liabilities, with accruals representing changes in noncash assets and liabilities. The financial analyst should be able to analyze whether a company’s use of discretion in implementing accruals facilitates or hampers investor decision making. The potential usefulness of the accrual system can be seen with the accruals and deferrals related to revenue recognition. For a company that sells a lot of its goods and services on credit terms, waiting until cash is received will not result in timely indication of the future cash flow generating ability of that enterprise. Instead, the company accrues revenues as the good is delivered or the service is provided. This is a desirable property of the accrual accounting system: It provides more timely and relevant information for decision making purposes. For example, if Cadence Cycling sold a bike during 2007 to a customer on credit, then under the cash basis of accounting that sale will not appear in the calculation of income for 2007. Instead, it will be recorded as revenue when the cash is collected in a future period. Under the accrual basis that sale will be recorded as revenue during 2007, with an adjustment for doubtful accounts (i.e., the full amount of the credit sale will be reduced based on an expectation of amounts that are not likely to be collected). The accrual basis of accounting therefore produces a net income figure that is more timely in communicating profit-generating activity to users of financial statements.

It is important to note that these same accruals bring with them discretion in estimating the amount of revenues that get allocated between fiscal periods. A number of questions must be answered before a number for revenue can be assigned to a given time period. For example, were the goods actually delivered? Were the services provided? Do the customers have recourse to return the merchandise? Do the customers have the ability, or credit-worthiness, to pay the receivable when it falls due? The answers to these questions are often subjective and create opportunities for strategic use of accrual accounting. By “strategic use” we mean that accounting numbers such as net income are important in a variety of contractual settings such as executive compensation. The economic incentives created by such contracts create an opportunity for management to be “strategic” or “opportunistic” when making determinations such as when a good has been provided, or how large a provision for doubtful accounts should be. We describe some of these incentives in more detail in Section 2.3.

Considerable research has examined whether cash basis or accrual basis performance measures are superior indicators of future cash flows and stock returns. The broad takeaway from the relevant literature is that accrual accounting earnings are superior to cash accounting earnings at summarizing company performance.1 However, accrual accounting aggregates numerous estimations with respect to the deferral and accrual of various revenue and expenses. For example, choices on useful life and residual value for the purposes of estimating periodic depreciation, choices on provisioning for doubtful accounts, choices on assumptions for computing postretirement obligations, etc., are all relevant in determining periodic net income. A simple way to isolate these aggregate accruals is to decompose accrued earnings into a cash flow and accrual component (we cover measurement of the components in Section 3.2). Extensive research has examined the benefits from this decomposition.2 There is clear evidence that the accrual component of earnings is less persistent (i.e., more transitory) than the cash component of earnings. (To explain persistence further, a completely persistent earnings stream is one for which a euro of earnings today implies a euro of earnings for all future periods.) The implication is that while accrual accounting is superior to cash accounting, the accrual component of earnings should receive a lower weighting than the cash component of earnings in evaluating company performance. This lower persistence is at least partly attributable to the greater subjectivity involved in the estimation of accruals.

The lower persistence of earnings resulting from high levels of accruals does not have to be a direct result of earnings management activity (i.e., deliberate activity aimed at influencing reporting earnings numbers, often with a goal of placing management in a favorable light). The nature of accrual accounting is to accrue and defer past, current, and anticipated future cash receipts and disbursements. The accrual process involves a significant amount of estimation of future cash receipts and payments, and a subjective allocation of past cash receipts and payments. In doing so, the accrual process creates accounts of varying reliability. For example, recording the net realizable value of receivables involves estimation of default risk across a portfolio of debtors. Other examples include estimating recoverable amounts of inventories, depreciating and amortizing long-lived assets, and estimating postretirement benefit obligations. Estimation errors (either intentional or unintentional) for the various asset, liability, and associated revenue and expense accounts will all lead to lower persistence in earnings. Collectively, these estimations manifest themselves in the magnitude of reported accruals. We will examine detailed examples related to these accounting distortions later in the reading. Specifically, we will introduce some broad measures of accruals that are useful from an investment perspective. To the extent that investors do not assign a lower weighting to accruals (because they are unable to fully comprehend the greater subjectivity involved in the estimation of accruals), securities become mispriced with respect to that information. A good analyst should not make this error: The accrual component of earnings should rationally receive a lower multiple in valuation than the cash component.

2.2. Placing Accounting Discretion in Context

In this section we outline some of the key areas of discretion embedded in the financial statements and identify why this discretion could be used strategically by management. Financial statements prepared under generally accepted accounting principles are riddled with estimates. These estimates lower the reliability of reported earnings as a result of both neutral estimation errors and the opportunistic use of discretion. For example, when estimating the allowance for doubtful accounts on credit sales and the related provision for bad debts, an estimate of 3 percent of sales may be made; but the actual rate of default could turn out to be 5 percent. The 2 percent understatement of expense in the year the provision was created may simply be an error in estimation or it could be the result of management intervention to report a lower expense. Disentangling whether the estimation error is neutral or strategic can be difficult, but the net result is the same for the financial analyst. If you see choices made that tend to over-(under-) state current income, then on average future cash flows will be lower (higher) respectively.

Examples of sources of accounting discretion include the following:

- Revenue recognition: Provisions for doubtful accounts, warranty provisions, returns and allowances, channel stuffing (forcing more products through a sales distribution channel than the channel can sell), timing of service or provision of goods, etc.

- Depreciation choices: Estimation of useful lives, residual value, method choice

- Inventory choices: Cost flow assumptions, obsolescence estimation, etc.

- Choices related to goodwill and other noncurrent assets: Periodic impairment tests

- Choices related to taxes: Valuation allowances

- Pension choices: Estimated return on plan assets, discount rates, wage growth, employee turnover, etc.

- Financial asset/liability valuation: Recent accounting pronouncements (e.g., SFAS 157 on Fair Value Measurement in the United States)3 focus on fair value as the basis for recording financial assets and liabilities. For certain types of financial assets and liabilities that rarely trade, there is considerable discretion in specifying the model inputs that would be used to assign a fair value.

- Stock option expense estimates: Volatility estimates, discount rates, etc.

This is only a partial list. Everything other than cash (excluding fraudulently reported cash) is the result of choice. We want to understand this choice and learn how to utilize disclosures in financial statements to quantify the extent that these choices are driving reported earnings.

It is important to keep in mind that the accounting discretion we discuss in this reading is part of a broader set of management decisions and interactions with financial markets that affect investor expectations. For example, the strategic use of accounting discretion can be combined with real business decisions such as the cutting of research and development activity or timing inventory purchases under LIFO accounting (permitted under U.S. GAAP but not IFRS), which also have a direct impact on financial statements. Management also can communicate directly with capital markets via their investor relations departments, conference calls, and conference presentations. There is a large industry set up to facilitate these communications, which are used by companies to explain company performance and help set expectations for future performance.

2.3. Manipulation Incentives

Financial statement information is used in a variety of settings that can create the incentive for the preparers of those statements to be opportunistic when reporting results. In particular, preparers may hope to influence capital markets and/or measured performance under various contracts. We examine these incentives in more detail in the following sections.

2.3.1 Capital Markets

When financial information is reported to capital markets, security prices move. This creates a clear incentive for management to report financial performance that meets or exceeds current expectations and to manage expectations going forward.

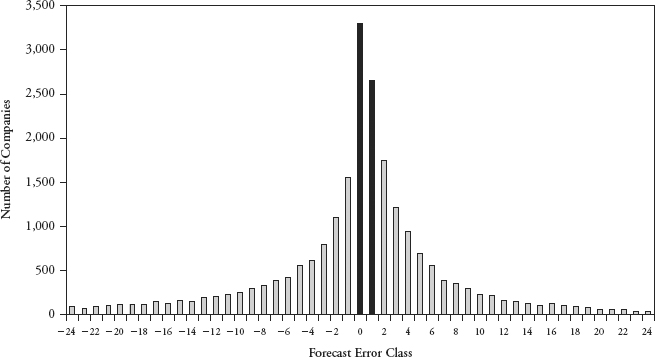

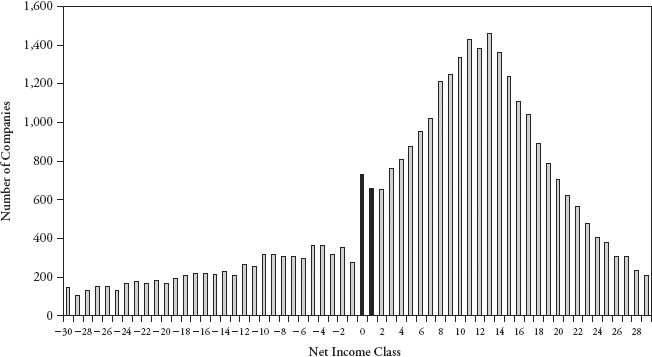

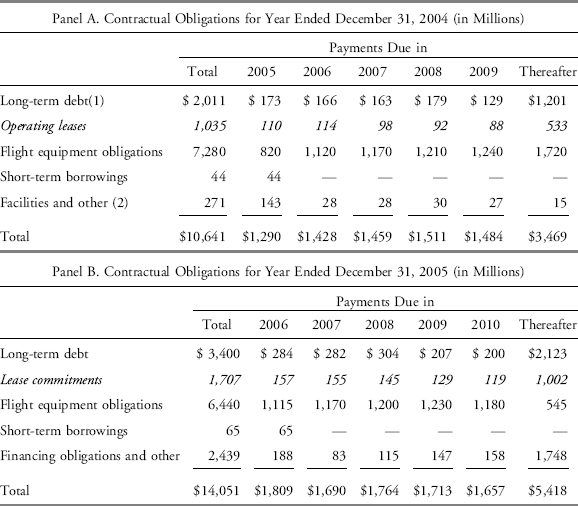

Research has focused on the propensity for companies to report earnings that meet various thresholds (e.g., beat historical earnings and beat consensus analyst forecasts). The exhibits following neatly summarize this phenomenon. Exhibit 16-1 reports the relative frequency of return on the market value equity (defined as net income divided by the market value of equity). The sample included is all U.S. Security and Exchange Commission (SEC) registrants from 1988–2003 (this is effectively all companies with securities that were publicly traded in the United States in that period). The horizontal axis groups companies into “NI (net income) class” buckets. These buckets are formed by cross-sectional ranking all companies into groups based on the magnitude of net income scaled by market capitalization. Each bar corresponds to a 50 basis point interval. For example, the bolded vertical bars correspond to firm-years where net income scaled by market capitalization is between 0 and 0.005 for the first bar, and between 0.005 and 0.01 for the second bolded bar. There is a clear “kink” in this distribution where more companies than expected report small profits (the bolded bars) compared to small losses. Some have claimed this kink is at least partly attributable to financial reporting manipulation.

EXHIBIT 16-1 Distribution of Net Income Deflated by Market Value of Equity

Source: Dechow, Richardson, and Tuna (2003).

Exhibit 16-2 reports the distribution of forecast errors for the same sample of companies. A forecast error is defined as the difference between reported earnings and the most recent consensus analyst earnings forecast prior to the earnings announcement. There is a clear incidence of an asymmetry around the “zero” forecast error (i.e., where more companies report earnings that slightly exceed sell-side analyst forecasts than companies that report earnings that just miss these forecasts). (Sell-side analysts work at firms that sell trading and related services.) This pattern appears to illustrate a combination of earnings management (i.e., opportunistic use of accruals) and earnings expectations management (i.e., encouraging analysts to forecast a slightly lower number than they would otherwise).

The target that the company is trying to achieve is a moving benchmark: the consensus sell-side forecast. Using strategic communications with the investment community, management is able to move this benchmark. Likewise, the reported earnings number is a moving target attributable to the discretion afforded to management. The focus on reporting earnings that meet consensus estimates has often been referred to as the earnings game. Indeed, there is evidence that this “game” is related to capital market pressures facing a company. If one looks at the pattern of forecast errors throughout the fiscal year, initial forecasts tend to be optimistic relative to reported earnings (i.e., analysts are forecasting a number early in the year that is greater than what the company ends up reporting), and the later forecasts tend to be pessimistic (i.e., analysts are forecasting a number later in the year that is less than what the company ends up reporting). This switch from early optimism to late pessimism leads to a positive earnings surprise when earnings are finally announced. Exhibit 16-3 summarizes this pattern for the same sample of companies, and it is clear that this pattern has become increasingly common in more recent years. Furthermore, this pattern is stronger for companies that are subsequently issuing equity, or where insiders are, on average, selling their equity stake.

Besides capital markets, a variety of contracts can provide manipulation incentives, as discussed in the next section.

2.3.2. Contracts

Accounting information is used in a variety of contracts, including managerial contracts and contracts related to financial securities. Both types of contracts can provide the incentive for management to use accounting discretion opportunistically.

For example, managerial compensation is typically set as a function of reported earnings numbers (either in absolute terms or relative to a benchmark) as well as linked to stock price information, which in turn is a function of reported earnings. As an example, Textron Inc. reports in its 2006 proxy statement that the performance criteria used for its short-term and long-term incentive plans includes various financial statement based measures including return on assets, and various profit margin and turnover measures. Financial statement information is regularly used as a basis for the determination of executive compensation. These contracts provide a very direct incentive for management to be opportunistic in their use of accounting discretion.

There are other contracts where accounting information also is used, such as debt contracts. Companies with outstanding debt are parties to one or more debt covenants (agreements between the company as borrower and its creditors) that typically have a variety of restrictions (e.g., the company must maintain a minimum interest coverage ratio to avoid technical default and potentially costly debt renegotiation) and possibly performance pricing grids where interest costs are explicitly tied to financial performance. Collectively, these contracts provide very clear incentives for management to strategically use the accounting discretion afforded to them.

2.4. Mechanisms Disciplining Management

The discussion thus far points to many opportunities for management to manipulate reported financial results. Should we therefore place very little value on the output of this system? No. Financial statements provide very useful information in part due to the standard set of rules according to which they are prepared despite the discretion allowed by the standards. There are many mechanisms curtailing abuse of that discretion. Some examples of the mechanisms ensuring truthful reporting include:

- External auditors. Every public company is required to have their financial statements audited by a registered auditor. This process provides independent verification of the statements. Specifically, the external auditor’s responsibility is to express an opinion on the truthfulness of consolidated financial statements, an opinion on management’s assessment of internal controls, and an opinion on the effectiveness of internal financial reporting controls. Auditors’ opinions that are other than “unqualified” reflect a disagreement about the treatment or disclosure of information in the financial statements.

- Internal auditors, audit committee, and the board. The board of directors, through its committees and oversight of internal auditors, has the capacity to act as a check on management.

- Management certification. For companies subject to the U.S. Sarbanes–Oxley Act of 2002, the CEO and CFO must now certify the financial statements increasing their litigation risk, so they have more personal risk than formerly in manipulating reported financial results.

- Lawyers. Class action lawsuits are a potentially effective way to mitigate incentives to game the financial reporting system.

- Regulators. Regulatory actions, up to criminal prosecution for certain misdeeds, can make managers think twice about their actions.

- General market scrutiny. Financial journalists, short sellers, activist institutions, employee unions, analysts, etc. are constantly studying financial statements in an effort to identify financial shenanigans.

3. FINANCIAL REPORTING QUALITY: DEFINITIONS, ISSUES, AND AGGREGATE MEASURES

In this section we lay out a broad framework for financial reporting quality, focusing on earnings quality. Earnings quality is typically defined in terms of persistence and sustainability. For example, analysts often claim that earnings are considered to be of high quality when they are sustainable or when they “expect the reported level of earnings to be sustained or continued.” These approaches have at their core a view on forecasting future cash flows or earnings that is central to valuation. A summary performance measure that better forecasts future cash flows or earnings is arguably of higher quality than one that is a less effective forecaster, as it better serves that valuation purpose. Other discussions of earnings quality look at the extent of aggressive or conservative choices that have been made in the financial statements of the companies under examination. For example, companies that have used an accelerated depreciation method, have high allowances for inventory obsolescence and doubtful accounts, or have large unearned revenue balances could be considered to have employed conservative accounting choices. This is because earnings have been depressed in the current period. However, given the range of potential earnings outcomes, simply equating choices that lower reported earnings with high earnings quality provides at best a marginal indicator of financial reporting quality as defined in the introduction of this reading. Reporting earnings that are too high or too low results in an inferior earnings measure for the purpose of forecasting future company performance. Accruals are not independent over time. Rather, accruals have a natural self-correcting property. For example, an aggressive accounting choice in the past that capitalized an excess amount of cost into a noncurrent asset will lead to larger write-downs of that asset in future periods. Thus, the earlier aggressive choice (avoiding expensing at the time of capitalization) is associated with a later conservative action (expensing). Focusing on changes in balance sheet accounts, or equivalently the multitude of accruals and deferrals embedded in net income, is an efficient and effective way to capture cross-sectional variation in earnings quality. These accrual-based measures capture both aggressive and conservative accounting choices that impair the ability of accrued earnings to forecast future company performance.

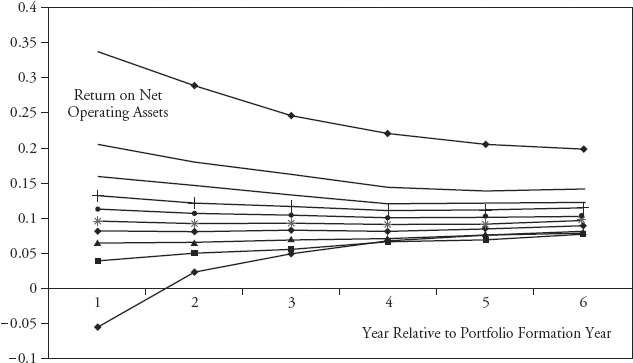

3.1. Mean Reversion in Earnings

Our focus on accruals and deferrals for earnings quality has valuation at its core. Our aim is to identify companies that have earnings that are more persistent or sustainable than their peers. In that context, the analyst should be aware of the empirically observed tendency of earnings at extreme levels to revert back to normal levels (mean reversion in earnings). The phenomenon has an economic explanation. Competitive markets (including the market for corporate control) tend to lead to correction of strategic or managerial problems causing poor performance; poorly performing businesses and segments tend to be abandoned. Subject to barriers to entry, capital migrates toward more profitable businesses and segments, increasing competition and reducing returns. The net effect of these competitive forces is to move earnings back to a “normal” level. Data analyzed by Nissim and Penman (2001) show that this pattern of mean reversion in earnings is very pervasive. Exhibit 16-4 summarizes the mean reverting behavior in return on net operating assets (RNOA) for a large sample of SEC registrants. Every year companies are sorted into ten equal groups and the average RNOAs for these ten portfolios are tracked over the next six years. There is a clear reversion back to a range between 8 and 20 percent by the end of six years.

EXHIBIT 16-4 Mean Reversion in Accounting Rates of Return (Return on Net Operating Assets)

Source: Reprinted from Review of Accounting Studies 6, no. 1, by Doron Nissim and Stephen Penman (March 2001), with kind permission of Springer Science and Business Media.

Understanding this reverting property of earnings is of fundamental importance for financial statement analysis. To build a meaningful forecast of future cash flows one should recognize that very low and very high earnings are not expected to continue into the future. Using information in accruals we can improve these forecasts of future cash flow further. As mentioned earlier, earnings have a cash flow and an accrual component. Algebraically, earnings are equal to cash flows plus accruals. When earnings are largely comprised of accruals, the evidence referenced in Section 2.1 suggests that future accounting rates of return and future cash flows would be lower. This is equivalent to saying that earnings will revert back to a normal level even quicker when earnings are largely comprised of accruals as opposed to cash flows. This is not surprising: The accrual component of earnings is where the accounting distortions are greatest and for which we expect there to be lower persistence.

In summary, earnings that are more persistent are viewed as higher quality. This decomposition of earnings into its accrual and cash flow components creates a superior forecast for future earnings and cash flows; furthermore, as already mentioned, earnings components that are less persistent should rationally receive a lower multiple in valuation. In a later section, we will walk through many examples of transactions that give rise to low quality earnings streams. One thing that is common to all of the examples of low earnings quality is the fact that current earnings are temporarily distorted relative to “true” earnings, due to various accounting choices, but cash flows are unaffected.

3.2. Measures of the Accrual Component of Earnings and Earnings Quality

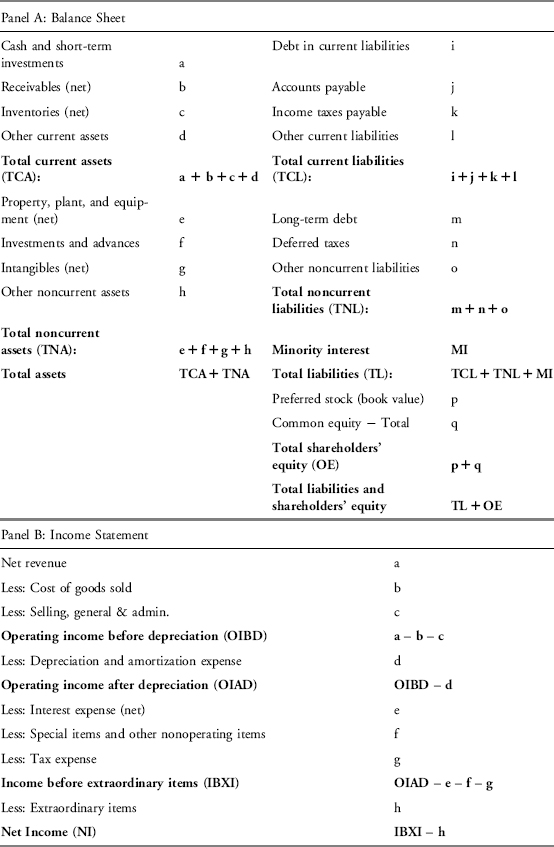

In this section we lay out the framework for measuring the cash and accrual components of earnings using standardized financial statements. We explain various measures of the accrual component of earnings (the cash component being the remainder after subtracting the accrual component from reported earnings). Finally, we present scaled measures of accrual components as simple measures of earnings quality that working analysts can readily compute and use.

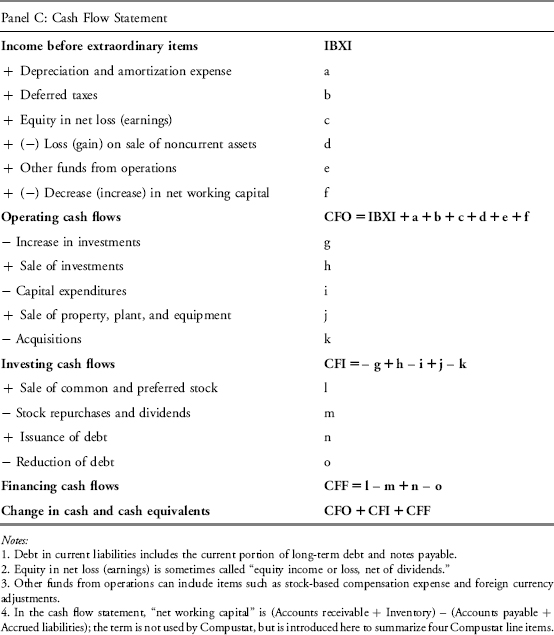

Exhibit 16-5 presents the three primary financial statements in standardized formats. The format selected is based on the one used by Compustat in processing the reported financials of companies trading in the United States, with simplifications.4 Using a standardized format has advantages in facilitating cross-sectional comparisons across companies.5 Note that “income before extraordinary items” is possible under U.S. Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (U.S. GAAP) but not under International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS), and “minority interest” must appear in the equity section under IFRS but can be placed in liabilities, in the equity section, or in between according to U.S. GAAP (Compustat places it in liabilities).6 Making adjustments for such differences where required is part and parcel of analysts’ work.

EXHIBIT 16-5 Financial Statements (in a Standardized Format)

The financial statements presented earlier are based on an accrual accounting system. Other than cash, every line item in the balance sheet is the result of subjective choices surrounding recognition and valuation rules. For example: (1) Receivables are reported on a net basis after making a determination that a sale was made and those credit sales are to customers with sufficient capacity to make good on the amounts they owe; (2) Inventories are also reported on a net basis assuming that there is sufficient future sales demand to be able to sell these items at an amount greater than their historical cost. Similar explanations can be made for every other line item in the balance sheet. Considerable discretion resides throughout the accrual-based financial statements.

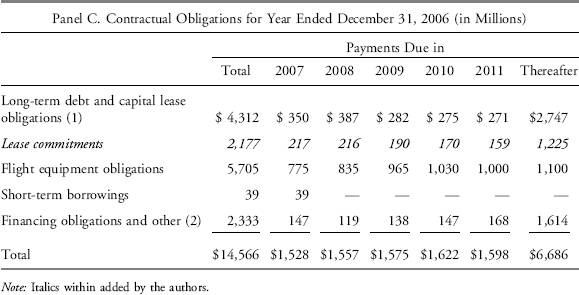

In contrast, financial statements based on a pure cash basis are devoid of this discretion: “cash is cash.” Absent fraud, there is no disputing ownership and the valuation of cash. Contrasting financial statements prepared on a cash basis with those prepared on an accrual basis is therefore a natural way to identify the extent of discretion embedded in the reported financial statements. Effectively, this amounts to comparing a pure change in cash measure of earnings with the reported earnings under the relevant set of accrual accounting principles (e.g., U.S. GAAP or IFRS). The difference is aggregate accruals or the accrual component of earnings:

There are several ways that we can decompose reported accrual earnings into a cash flow and accrual component. We can focus on information in the balance sheet, or we can focus on information in the statement of cash flows. We prefer the latter approach because it generates a cleaner measure that is free from the effects of noncash acquisitions and foreign currency translation adjustment effects. We now outline the two approaches to this decomposition of accruals and the definition of a quantity (“accrual ratio”) for comparing accruals across companies or for one company over time.

First, using balance sheet data, we can measure the net change across all noncash accounts to compute the aggregate accruals for that fiscal period. With the sample balance sheet reported earlier, aggregate accruals are simply the change in net assets (net of the cash and debt-related accounts) from the start to the end of the period. We first define net operating assets (NOA) as the difference between operating assets (total assets less cash) and operating liabilities (total liabilities less total debt):

We exclude cash (shorthand here for “cash and short-term investments”) and debt from our measure as these accounts are essentially discretion free. (This is not entirely true as there are some accounting accruals/deferrals embedded in debt, e.g., amortization of discounts/premium, but these can be ignored for our purposes here.)

From a balance sheet perspective, we measure aggregate accruals for period t as the change in NOA over the period:

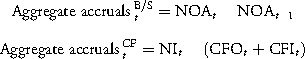

We can call the measure presented in Equation 16.3 balance-sheet-based aggregate accruals. To adapt the measure as an indicator of earnings quality, it must be made comparable across companies by adjusting for differences in company size. An easy way to do the adjustment is to deflate (i.e., scale) the aggregate accrual measure by the average value of NOA. If one just used the opening or ending value of NOA as the scaling quantity, the ratio would be distorted by companies that have experienced significant growth or contractions during the fiscal period. The scaled measure (which we can call the balance-sheet-based accruals ratio) is our first measure of financial reporting quality and given by

The accruals measures defined in Equations 16.3 and 16.4 involve the summation of all of the line items of the balance sheet. If you are interested in subcomponents of accrual activity, then simply focus on the relevant line item from the balance sheet. For example, looking at the change in net receivables over a fiscal period deflated by average NOA will give you a sense of the magnitude of accrued revenue attributable to net credit sales.

We can also look at the statement of cash flows. For this approach we are looking at the difference between reported accrual earnings and the cash flows attributable to operating and investing activities. From a cash flow statement perspective, a measure of aggregate accruals can be defined as follows:7

We can call this cash-flow-statement-based aggregate accruals. The corresponding scaled measure (cash-flow-statement-based accruals ratio) is our second simple measure of financial reporting quality:

The measures in Equations 16.5 and 16.6 aggregate all of the operating and investing activities and their impact on cash flows relative to accrued earnings. The result is a cash-flow-statement-based measure of aggregate accruals. The inclusion of the cash flow from investing activities (CFIt) in Equations 16.5 and 16.6 may require explanation. From a valuation perspective, there are essentially only two sides to the company: the operating side (broadly conceived) and the financing side. However, the cash flow statement splits the operating side into “operating” and “investing” pieces (roughly, current and noncurrent operating pieces). When calculating a broad accruals ratio, the appropriate treatment is to include both cash flow pieces (CFO and CFI). In applying Equations 16.5 and 16.6, the analyst should make any needed adjustments for differences in the cash flow statement treatment of interest and dividends across companies being examined.8 These adjustments ensure consistency in the treatment of operating and financing activities. For example, if Company A treats interest paid as an operating cash outflow (under U.S. GAAP) and Company B treats interest paid as a financing cash flow (under IFRS), the systematic differences in leverage across the two companies could create significant differences in a computed aggregate accrual measure. Treating interest paid consistently across the companies (e.g., as a financing cash outflow) will mitigate this problem.

Example 16-1 illustrates the calculation of the ratios for an actual company.

EXAMPLE 16-1 The Coca-Cola Company: An Illustration of Accrual Analysis

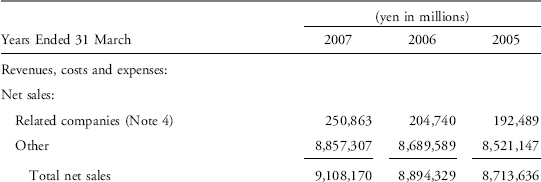

Recent financial statements for the Coca-Cola Company (NYSE: KO) have been put in the format of Exhibit 16-5.9

The Coca-Cola Company Financial Statements in Standardized Format Year Ended 31 December (Amounts in $Millions)

| Panel A: Balance Sheet | 2006 | 2005 |

| Cash and short-term investments | 2,590 | 4,767 |

| Receivables (net) | 2,587 | 2,281 |

| Inventories (net) | 1,641 | 1,424 |

| Other current assets | 1,623 | 1,778 |

| Total current assets | 8,441 | 10,250 |

| Property, plant, and equipment (net) | 6,903 | 5,786 |

| Investments and advances | 6,783 | 6,922 |

| Intangibles (net) | 5,135 | 3,821 |

| Other noncurrent assets | 2,701 | 2,648 |

| Total noncurrent assets | 21,522 | 19,177 |

| Total assets | 29,963 | 29,427 |

| Debt in current liabilities | 3,268 | 4,546 |

| Accounts payable | 929 | 2,315 |

| Income taxes payable | 567 | 797 |

| Other current liabilities | 4,126 | 2,178 |

| Total current liabilities | 8,890 | 9,836 |

| Long-term debt | 1,314 | 1,154 |

| Deferred taxes | 608 | 352 |

| Other noncurrent liabilities | 2,231 | 1,730 |

| Total noncurrent liabilities | 4,153 | 3,236 |

| Minority interest | 0 | 0 |

| Total liabilities | 13,043 | 13,072 |

| Preferred stock (book value) | 0 | 0 |

| Common equity − Total | 16,920 | 16,355 |

| Total shareholders’ equity | 16,920 | 16,355 |

| Total liabilities and shareholders’ equity | 29,963 | 29,427 |

| Panel B: Income Statement | 2006 | |

| Net revenue | 24,088 | |

| Less: Cost of goods sold | 7,358 | |

| Less: Selling, general & admin. expenses | 9,195 | |

| Operating income before depreciation | 7,535 | |

| Less: Depreciation and amortization expense | 938 | |

| Operating income after depreciation | 6,597 | |

| Less: Interest expense (net) | 220 | |

| Plus: Special items and other nonoperating items | 201 | |

| Less: Tax expense | 1,498 | |

| Income before extraordinary items | 5,080 | |

| Less: Extraordinary items | 0 | |

| Net income | 5,080 | |

| Panel C: Statement of Cash Flows | 2006 | |

| Income before extraordinary items | 5,080 | |

| + Depreciation and amortization expense | 938 | |

| + Deferred taxes | −35 | |

| + Equity in net loss (earnings) | 124 | |

| + (−) Loss (gain) on sale of noncurrent assets | −303 | |

| + Other funds from operations | 768 | |

| + (−) Decrease (increase) in net working capital | −615 | |

| Operating cash flows | 5,957 | |

| − Increase in investments | 1,045 | |

| + Sale of investments | 640 | |

| − Capital expenditures | 1,407 | |

| + Sale of property, plant, and equipment | 112 | |

| − Acquisitions | 0 | |

| Investing cash flows | −1,700 | |

| + Sale of common stock | 148 | |

| − Stock repurchases and dividends | 5,327 | |

| + Issuance of debt | 617 | |

| − Reduction of debt | 2,021 | |

| Financing cash flows | −6,583 | |

| Less: Exchange rate effects | 65 | |

| Change in cash and cash equivalents | −2,261 |

Based on the information given, address the following problems:

1. Calculate net operating assets for Coca-Cola for 2006 and 2005.

2. Calculate balance-sheet-based aggregate accruals for Coca-Cola for 2006.

3. Calculate the balance-sheet-based accruals ratio for Coca-Cola for 2006.

4. Calculate cash-flow-statement-based aggregate accruals for Coca-Cola for 2006.

5. Calculate the cash-flow-statement-based accruals ratio for Coca-Cola for 2006.

6. State and explain which of the measures calculated in Problems 1 through 5 would be appropriate to use in evaluating relative financial reporting quality of a group of companies.

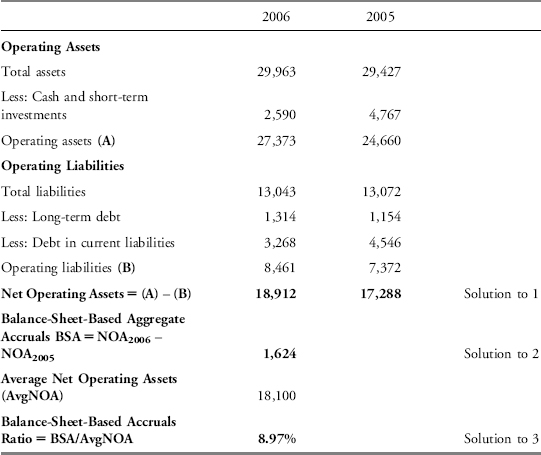

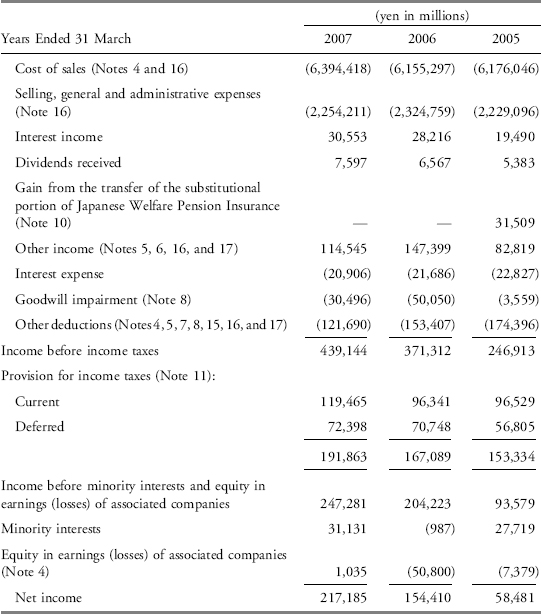

Solutions to 1, 2, and 3: These are given in the worksheet here.

Balance Sheet Computation of Aggregate Accruals

Problem 1: The amount of net operating assets is found as the difference between operating assets (total assets minus cash and short-term investments) and operating liabilities (total liabilities minus total debt). For 2005 and 2006, net operating assets amount to $17,288 million and $18,912 million, respectively.

Problem 2: The amount of balance-sheet-based aggregate accruals for 2006 is found as the change in net operating assets from 2005 to 2006. This amount is $1,624 million.

Problem 3: The balance-sheet-based accruals ratio for 2006 is found by dividing balance-sheet-based aggregate accruals for 2006, $1,624 million, by average net operating assets, (18,912+17,288)/2 = $18,100 million. This ratio is equal to 1,624/18,100 = 8.97 percent.

Solutions to 4 and 5: These are given in the worksheet here.

Cash Flow Statement Computation of Aggregate Accruals

| 2006 | ||

| Income before Extraordinary Items | 5,080 | |

| Less: Operating Cash Flows | 5,957 | |

| Less: Investing Cash Flows | −1,700 | |

| Cash-Flow-Statement-Based Aggregate Accruals (A) | 823 | Solution to 4 |

| Cash-Flow-Statement-Based Accruals Ratio = (A)/AvgNOA | 4.55% | Solution to 5 |

Note: AvgNOA is 18,100 (see previous worksheet).

Solution to 6: Among the measures presented in Problems 2 through 5, only the size-scaled measures calculated in Problems 3 and 5 are appropriate for cross-company comparisons. The unscaled measures in Problems 2 and 4 would be affected by differences in company size.

Consistent with the earlier discussion on the balance sheet approach to measuring accruals, we also could focus on current versus noncurrent accruals by looking only at the difference between reported income and operating cash flows for current accruals. It is important to note that while the two approaches (balance sheet and statement of cash flows) are conceptually equivalent, they will not generate the exact same numbers due to a combination of noncash acquisitions, currency translation, and inconsistent classification across the balance sheet and statement of cash flows. These differences, however, are typically small and can be ignored for our purpose. The typical correlation between a broad accrual measure based on balance sheet data with one based on statement of cash flow data is in excess of 0.80. The important thing to remember is to compare companies using the same method. If you prefer to use a balance sheet approach or a statement of cash flow approach, be sure to keep that method constant across companies. If you use different methods across companies, this will distort your comparison. But using one approach systematically will give a very similar rank ordering of companies as using the other approach systematically.

3.3. Applying the Simple Measures of Earnings Quality

The simple measures of earnings quality defined by Equations 16.4 and 16.6 are an effective way to partition companies into low and high earnings quality groups. Given the broad discretion afforded to management, it can be difficult to identify specifically which accrual or deferral was manipulated in a given fiscal period. Rather than attempt to measure discretion embedded within each accrual, an effective alternative is to focus on the aggregate. This aggregate measure will reflect the portfolio of discretion and its impact on income for a given fiscal period. In this section we give further examples to illustrate the measures. Example 16-2 compares two companies. In contrast to Example 16-1, the original account labels have been retained in the example.

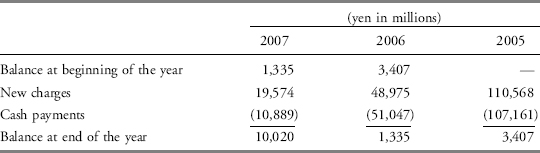

EXAMPLE 16-2 A Quality-of-Earnings Comparison of Two Companies

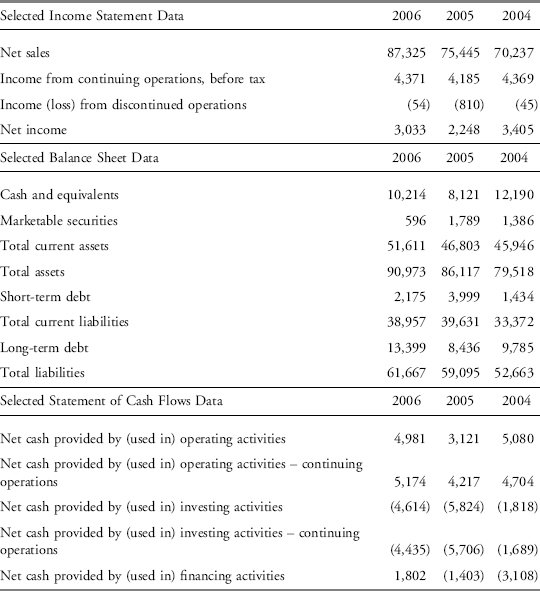

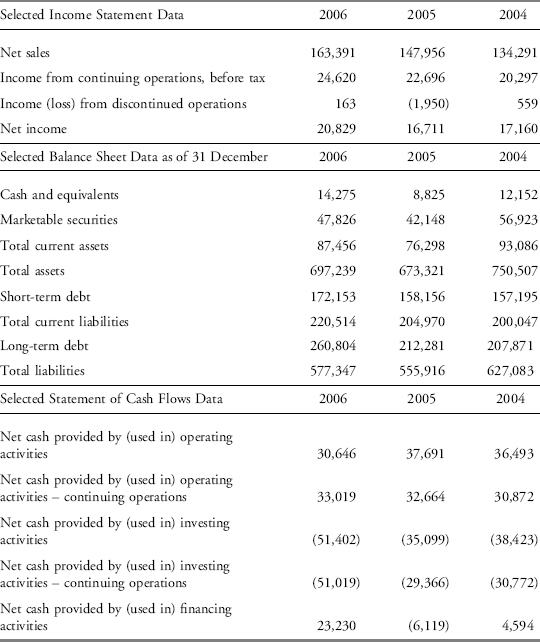

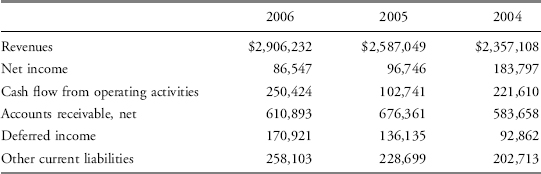

Siemens, AG is a global electronics and electrical engineering company headquartered in Munich, Germany. Selected data (in € millions) from Siemens’ financial statements for the years ended 30 September 2006, 2005, and 2004 are presented here.

Siemens, AG Fiscal Years Ended 30 September (€ in millions)

General Electric is a diversified global industrial corporation headquartered in Fairfield, Connecticut, USA. Selected data (in $ millions) from GE’s financial statements for the years ended 31 December 2006, 2005, and 2004 are presented here.

General Electric Company and Consolidated Affiliates, Years Ended 31 December (in Millions of $)

Based on the information given, address the following:

1. Calculate net operating assets for Siemens and GE for each year presented.

2. Calculate aggregate accruals using both the balance sheet and cash flow statement methods for Siemens and GE for each year presented.

3. Calculate the balance-sheet-based and cash-flow-statement-based accruals ratios for Siemens and GE for each year presented.

4. A. State and explain which company had higher earnings quality in 2005 and 2006.

B. Identify any trends in earnings quality for each company.

5. Would the results of question 4 be different if the accruals ratios were calculated based only on continuing operations?

6. General Electric recorded net financing receivables of $334,232 in 2006 and $292,639 in 2005. It describes these receivables in the notes to its financial statements as largely relating to direct financing leases. Evaluate this disclosure with respect to GE’s earnings quality.

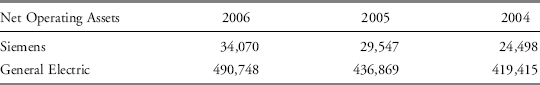

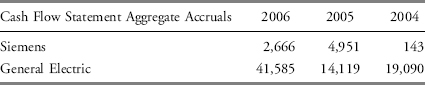

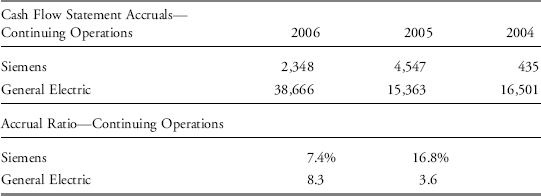

Solution to 1: Net operating assets is defined as (total assets − cash and marketable securities) − (total liabilities − total debt). For example, in 2006 Siemens reported total assets of 90,973 and cash and marketable securities of 10,214+596 = 10,810. Total liabilities were 61,667 and total debt was 2,175+13,399 = 15,574. (90,973 − 10,810) − (61,667 − 15,574) = 80,163 − 46,093 = 34,070. The values for each firm are summarized on the following page.

Solution to 2: Balance sheet aggregate accruals are defined as the change in net operating assets. As such, only two years’ worth of accruals can be calculated from the data given. For example, for Siemens, using the answers to Problem 1, balance sheet aggregate accruals for 2006 equal €34,070 − €29,547 = €4,523.

| Balance Sheet Aggregate Accruals | 2006 | 2005 |

| Siemens | 4,523 | 5,049 |

| General Electric | 53,879 | 17,454 |

Cash flow statement aggregate accruals are defined as net income − (cash flows from operating activity+cash flows from investing activity). For example, for Siemens in 2006, cash flow statement aggregate accruals are found as NI of €3,033 minus [CFO of €4,981+(CFI of −€4,614)] = €3,033 minus €367 = €2,666.

Solution to 3: The accrual ratio is defined as aggregate accruals divided by average net operating assets. Because the denominator requires an average of two years’ data, only two years of accrual ratios can be calculated. For example, for Siemens, average net operating assets for 2006 were (€34,070+€29,547)/2 = €31,808.5. With aggregate accruals for 2006 of €4,523 and €2,666 by the balance sheet and cash flow statement methods, respectively, the corresponding accrual ratios were €4,523/€31,808.5 = 14.2 percent and €2,666/€31,808.5 = 8.4 percent.

| Balance-Sheet-Based Accrual Ratio | 2006 (%) | 2005 (%) |

| Siemens | 14.2 | 18.7 |

| General Electric | 11.6 | 4.1 |

| Cash-Flow-Statement-Based Accrual Ratio | 2006 (%) | 2005 (%) |

| Siemens | 8.4 | 18.3 |

| General Electric | 9.0 | 3.3 |

Solution to 4:

A. Using the balance-sheet-based accrual ratio, General Electric has higher earnings quality (i.e., lower accruals ratio) in both years. Using the cash-flow-statement-based measure, GE actually shows lower earnings quality than Siemens only in 2006.

B. Using either earnings quality measure, Siemens shows improving earnings quality from 2005 to 2006, while GE shows deteriorating earnings quality.

Solution to 5: Subtracting the results of discontinued operations from net income and using the cash flow data from continuing operations, the results of the calculations are:

Using continuing operations does not significantly alter either the level or trends in accruals for these companies.

Solution to 6: The $41,593 million change in financing receivables accounts for a large portion of GE’s $53,879 million change in net operating assets. Compared to treating the leases as operating leases (see the reading on long-term liabilities), accounting for leases as direct financing leases increases net income in the early years of a lease but the same total net income is recognized over the lease life. Under direct financing lease accounting, operating cash flow is lower, but investing cash flows are higher. When considering the cash versus accrual portions of earnings, this disclosure allows us to conclude that GE’s 2006 earnings are likely less persistent (of lower quality) than its 2005 earnings.

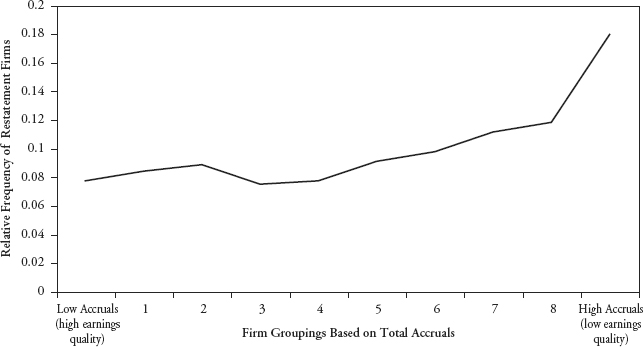

Broad measures of aggregate accruals are quite effective in identifying companies with financial reporting quality issues. Using a broad sample of earnings restatements from 1979 through 2002, Richardson, Tuna, and Wu (2002) found strong evidence that these restatements are concentrated in companies reporting the highest level of total accruals. Exhibit 16-6 summarizes these findings. Every year, SEC registrants are sorted into ten equal-sized groups based on the magnitude of total accruals, using the statement of cash flow definition (Equation 16.6). Exhibit 16-6 reports the relative frequency of earnings restatements across these ten equal-sized groups. The upward sloping line is quite telling: Of the 440 earnings restatements examined, there is a concentration in the highest accrual group (low earnings quality). Specifically, for the lowest accrual group (high earnings quality) only 7.5 percent of the 440 restatements are to be found, but in the highest accrual group we see 18 percent of the 440 restatement companies.

EXHIBIT 16-6 Relative Frequency of Earnings Restatements as a Function of Aggregate Accruals

Source: Richardson, Tuna, and Wu (2002).

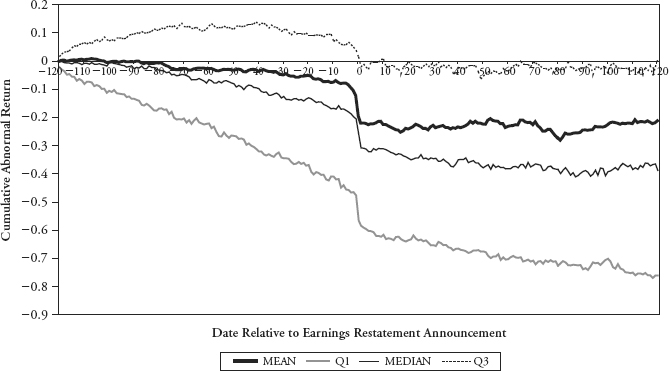

This ability to discriminate restatement companies from nonrestatement companies is beneficial to analysts looking to avoid significant “torpedoes” in their portfolios. This clearly can be seen in Exhibit 16-7. In this exhibit we plot the cumulative equity returns for the 440 earnings restatement companies examined previous. We cumulate stock returns for 120 trading days either side of the first press release describing the earnings announcement (i.e., the “0” point on the horizontal axis corresponds to the announcement date). There is a marked decrease in market value around this announcement. For the average company in that group, the loss of market value in the few days surrounding the announcement of the restatement is around 10 percent. Having information ahead of time as to the likelihood of a restatement is clearly of value to the equity investor. The earlier analysis demonstrates just that: Broad accrual measures are effective in identifying egregious accounting irregularities of the type that precipitate earnings restatements. Importantly, these measures identify such companies well ahead of the restatement announcement. For the 440 restatement companies examined, the announcement date is (on average) more than one year after the fiscal year during which the alleged manipulation occurred.

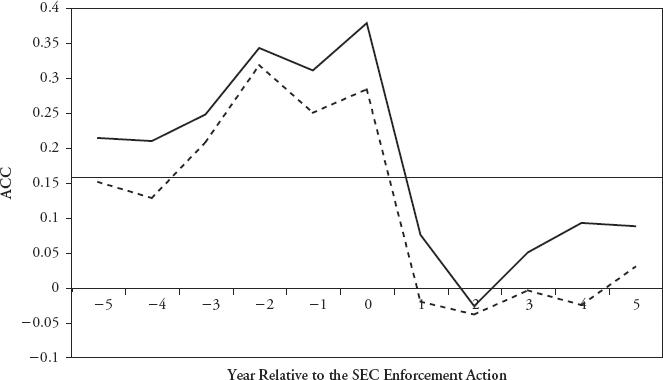

To make this point even more clear, research also has shown that broad measures of accruals are also leading indicators of SEC enforcement actions. Exhibit 16-8 reports aggregate accruals for companies subject to SEC enforcement actions. (The measure used [ACC] is the same as what we have called the balance-sheet-based accruals ratio in this reading.) Aggregate accruals are tracked for five years on either side of the period of alleged manipulation giving rise to the enforcement action. The bold (hatched) line reports the average (median) aggregate accruals for the SEC enforcement action sample. For comparison purposes the horizontal line shows the aggregate accruals for the average listed company (a little over 15 percent). Note the clear pattern for companies subject to enforcement actions from the SEC: The accrual measure peaks at between 30 and 35 percent in the two years prior to the SEC enforcement action.

EXHIBIT 16-7 Cumulative Abnormal Returns around Earnings Restatements

Source: Richardson, Tuna, and Wu (2002).

EXHIBIT 16-8 Aggregate Accruals (ACC) around SEC Enforcement Action

Source: Richardson, Sloan, Soliman, and Tuna (2006).

It is important to note that while this broad approach does not tell us which accruals were used as part of that manipulation, it is effective at summarizing all sources of accruals that were used to achieve an earnings target. More detailed analysis focusing on components of total accruals that are particularly germane to a given sector is likely to generate even more effective discriminatory power to identify earnings restatements. Some examples include focusing on the unearned revenue accounts in the software industry, claim loss development reserves in the insurance industry, loan loss provisions for financial institutions, fair value adjustments for complicated derivative instruments held by financial institutions, inventory adjustments for manufacturing companies, etc.

In the next section we focus on the various component accruals (e.g., provision for doubtful accounts, depreciation choices, unearned revenue, inventory obsolescence, etc.) that drive the aggregate accrual measures we have discussed so far.

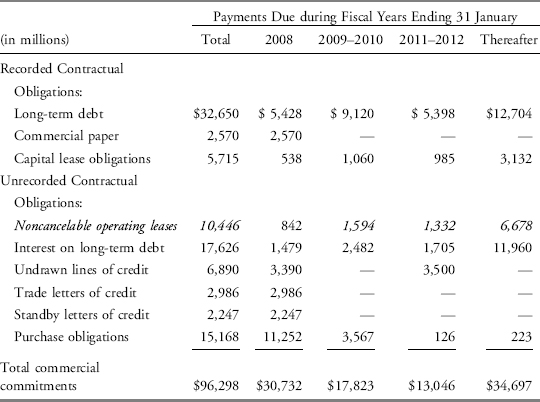

4. A FRAMEWORK FOR IDENTIFYING LOW-QUALITY FINANCIAL REPORTING

This section focuses on specific approaches and measures used to quantify financial reporting quality. This framework builds on a sound understanding of the key risk and success factors facing the company. As with any quantitative analysis, the quality of the output depends on the quality of inputs and on a structured analysis of those inputs. Furthermore, the relevance of the reporting quality measures we will discuss (1) varies across companies and (2) can vary through time for a given company. As examples of Point 1, measures related to inventory are particularly relevant for retail and manufacturing companies, measures relating to depreciation choices are particularly relevant for capital intensive companies, and measures relating to off-balance sheet financing vehicles are especially relevant for financial institutions or entities with linked financial subsidiaries. As an example of Point 2, it is often easier for management of a company to “hide” their use of discretion in periods of growth. Consequently, the most effective way to utilize the quantitative measures discussed later is through a combination of peer group comparison and year-over-year changes. Sector neutralizing measures of financial reporting quality—by subtracting the mean or median ratio for a given sector group from a given company’s ratio—are particularly useful in identifying companies with extreme good or poor quality. However, the degree of homogeneity within a sector or industry group may vary, so supplementing this kind of analysis with information on how the company itself has changed through time can help mitigate any heterogeneity. The company may change through time via divestitures, acquisitions, and changes in strategy. Such changes need to be kept in mind so you have a comparison that is as close to “apples to apples” as possible. Finally, as with any ratio analysis, the analyst should work with standardized financial statements so companies of different sizes are comparable. This is easily achieved by dividing a flow measure from the income statement or statement of cash flows by a measure from the balance sheet such as average total assets.

As we work through the various line items of the financial statements following, it is important to keep in mind the link between the primary financial statements. If there is an issue to be measured in the context of revenues or expenses, there will be an associated implication on the net assets reported in the balance sheet. To keep the sections manageable, we have focused on revenue and expense quality issues. We could easily have included a complete asset and liability section as well, but this would be the flip side of a combination of the revenue and expense items. For example, discussion on the unearned revenue account, which typically appears as part of other current liabilities on the balance sheet, is subsumed by the discussion of revenue recognition. Therefore, instead of repeating our discussion, we highlight the relevant asset and liability accounts associated with the respective revenue and expense accounts.

4.1. Revenue Recognition Issues

Misstating current revenue, recognizing revenue early, or classifying nonoperating income or gains as resulting from operating activities can make current operating performance appear better than it actually is—generally impairing the persistence or sustainability of reported earnings. The following sections highlight the major types of revenue recognition issues.

4.1.1. Revenue Misstatement

This section focuses on the discretion available when reporting revenue. Revenue can be over- or understated for a given period. Examples of overstatement include recording smaller provisions for doubtful accounts and warranty provisions. Examples of understatement include recording opportunistic use of unearned revenue. We will discuss these in turn.

4.1.1.1. The Range of Problems

Revenue accounting is one of the simplest, yet most challenging aspects of interpreting financial statements. As described in Section 2, accrual accounting records revenue not when cash is collected, but when a good or service has been provided to the customer. Total revenue reported in a given fiscal period is equal to the cash collected from customers plus the increase in net accounts receivable less the increase in unearned revenue (unearned revenue or deferred revenue is payment received in advance of providing a good or service). Receivables capture credit sales made in the past that as yet have not been collected. While companies have to report these receivables on a net basis by making a best guess as to what will become uncollectible, there is considerable discretion in determining the amount that is expected to be uncollectible. Likewise, unearned revenue contains discretion. The existence of this account typically lowers the reported revenue relative to cash received in the current period. But note that unearned revenues from prior fiscal periods can be used to create revenue in the current fiscal period. For example, if a company collected cash in 2006 for services to be provided over several periods the appropriate treatment is to record that cash collection as a liability in 2006. During future periods a determination has to be made as to whether the services have in fact been provided. Oftentimes there is discretion in deciding when a service has been provided, especially for software companies where the service and licensing agreements are typically bundled together. Related to estimates about credit sales and unearned revenue, companies also must estimate warranty provisions, and sales returns and allowances. The net effect of all of these estimates is the single line item, total revenue, reported at the top of the income statement. Collectively, the discretion embedded in the revenue line item is the culprit for the majority of earnings restatements, fraud cases, and related SEC enforcement actions (Huron Consulting reports that the main driver of earnings restatements in recent years is revenue recognition issues).

4.1.1.2. Warning Signs

To detect quality issues with reported revenues, it is best to focus on the balance sheet accounts associated with revenue (accounts receivable and unearned revenue). Large changes in these accounts should be viewed as “red flag” indicators of revenue quality issues. Specifically, large increases in accounts receivable or large decreases in unearned revenue are indicators of low-quality revenue. Companies reporting earnings where a large portion of the revenue is attributable to growth in receivables or a contraction in unearned revenue, on average report lower accounting rates of return and cash flows in the future, and these earnings reversals are not anticipated in a timely fashion by the stock market.10

We can use the example of Microsoft to illustrate various revenue recognition issues. In Exhibit 16-9 we see the balance sheet for the 30 June 2007 fiscal year for Microsoft.

EXHIBIT 16.9 Microsoft Corporation Balance Sheets, Fiscal Year Ended 30 June 2007 and 30 June 2006 (in $ Millions)

Note: Italics added by authors.

| 30 June | 2007 | 2006 |

| Assets | ||

| Current assets: | ||

| Cash and equivalents | $ 6,111 | $ 6,714 |

| Short-term investments (including securities pledged as collateral of $2,356 and $3,065) | 17,300 | 27,447 |

| Total cash and short-term investments | 23,411 | 34,161 |

| Accounts receivable, net of allowance for doubtful accounts of $117 and $142 | 11,338 | 9,316 |

| Inventories | 1,127 | 1,478 |

| Deferred income taxes | 1,899 | 1,940 |

| Other | 2,393 | 2,115 |

| Total current assets | 40,168 | 49,010 |

| Property and equipment, net | 4,350 | 3,044 |

| Equity and other investments | 10,117 | 9,232 |

| Goodwill | 4,760 | 3,866 |

| Intangible assets, net | 878 | 539 |

| Deferred income taxes | 1,389 | 2,611 |

| Other long-term assets | 1,509 | 1,295 |

| Total assets | $63,171 | $69,597 |

| Liabilities and stockholders’ equity | ||

| Current liabilities: | ||

| Accounts payable | $ 3,247 | $ 2,909 |

| Accrued compensation | 2,325 | 1,938 |

| Income taxes | 1,040 | 1,557 |

| Short-term unearned revenue | 10,779 | 9,138 |

| Securities lending payable | 2,741 | 3,117 |

| Other | 3,622 | 3,783 |

| Total current liabilities | 23,754 | 22,442 |

| Long-term unearned revenue | 1,867 | 1,764 |

| Other long-term liabilities | 6,453 | 5,287 |

| Commitments and contingencies | ||

| Stockholders’ equity: | ||

| Common stock and paid-in capital − shares authorized 24,000; outstanding 9,380 and 10,062 | 60,557 | 59,005 |

| Retained deficit, including accumulated other comprehensive income of $1,654 and $1,229 | (29,460) | (18,901) |

| Total stockholders’ equity | 31,097 | 40,104 |

| Total liabilities and stockholders’ equity | $63,171 | $69,597 |

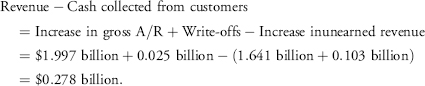

There is a roughly $1.6 billion increase in the short-term unearned revenue account (the opening balance is $9.138 billion and the closing balance is $10.779 billion, creating a positive change of $1.641 billion), and a roughly $0.1 billion increase in the long-term unearned revenue account (the opening balance is $1.764 billion and the closing balance is $1.867 billion, creating a positive change of $0.103 billion). There is also a roughly $2 billion increase in gross accounts receivable11 (the opening balance is $9.458 billion and the closing balance is $11.455 billion, creating a positive change of $1.997 billion). Write-offs will reduce the gross accounts receivable balance but do not reflect cash collection. In the absence of footnote information, we can infer a $0.025 billion write-off from the decrease in the allowance for doubtful accounts. To place these magnitudes in context, Microsoft reported revenue of $51.122 billion and net income of $14.065 billion for the fiscal period. The difference between revenue and cash collected from customers can be computed by aggregating the changes in accounts receivable and unearned revenue accounts as follows:

The net effect of the increase in receivables, write-offs, and increase in unearned revenue is to report revenue greater by $0.278 billion relative to cash collected from customers. The magnitude of the absolute changes in these accounts is over $3.5 billion, suggesting that Microsoft has considerable flexibility in reporting revenue in a given fiscal period. For example, the unearned revenue account could be built up in periods of strong growth as customers prepay for services, and tapped into when times are tough. In effect, with the unearned revenue account, Microsoft has flexibility to be strategic as to when it chooses to recognize revenue. Note that few companies disclose unearned revenue separately in the financial statements; however, this information can often be found in supplemental footnote disclosures to the financial statements.

To place the accrual items described earlier (change in accounts receivable and change in unearned revenue) in context, we can express these changes as a fraction of average net operating assets. For the year ended 30 June 2007, Microsoft reports in millions of dollars: opening (closing) total assets of $69,597 ($63,171), opening (closing) cash and short-term investments of $34,161 ($23,411), opening (closing) total liabilities of $29,493 ($32,074), and opening (closing) total debt of $0 ($0). Using the balance-sheet-based accruals ratio described in Equation 16.4, we can compute aggregate accruals as follows:

| 2007 | 2006 | |

| Operating Assets | ||

| Total assets | 63,171 | 69,597 |

| Less: Cash and short-term investments | 23,411 | 34,161 |

| Operating assets (OA) | 39,760 | 35,436 |

| Operating Liabilities | ||

| Total liabilities | 32,074 | 29,493 |

| Less: Long-term debt | 0 | 0 |

| Less: Debt in current liabilities | 0 | 0 |

| Operating liabilities (OL) | 32,074 | 29,493 |

| Net Operating Assets NOA = OA − OL | 7,686 | 5,943 |

| Balance-sheet-based aggregate accruals (= NOA[2007] − NOA[2006]) | 1,743 | |

| Average Net Operating Assets | 6,814.5 | |

| Balance-Sheet-Based Accruals Ratio (= 1,743/6,814.5) | 25.58% |

The revenue-related accruals in accounts receivable and unearned revenue, calculated as the increase in gross accounts receivable plus write-offs minus the increase in unearned revenue, total $278 million, which accounts for about 16 percent of the total accruals ($278 million/$1,743 million) for the 2007 fiscal year. There are other ways to use this information to make statements about earnings quality. For example, measures of days’ sales outstanding (DSO) are useful to inform about revenue quality. DSO is simply the ratio of net accounts receivable divided by total revenue multiplied by 365. This ratio gives a sense for how quickly the company is able to convert its credit sales into cash. Increases in this ratio are a red flag for questionable credit sales that take longer to convert into cash. Of course, in assessing this ratio, one should be careful to see if the company’s credit policy or product mix has changed substantially, or whether the company has securitized or factored its receivables (this leads to a dramatic lowering of DSO, which is not sustainable). If you notice that a company has securitized a large portion of its receivables, then do not treat the accompanying improvement in DSO as a signal of improving earnings quality because it is a one-off occurrence. For example, Federated Stores sold its credit card business in 2005, effectively lowering its DSO ratio to zero.

4.1.2. Accelerating Revenue

In addition to the issues described previously relating to credit sales and unearned revenue, there is also considerable discretion as to when a sale has been made. The issue here is deciding in which fiscal period revenue should be recognized.

4.1.2.1. The Range of Problems

Related to the discussion in Section 4.1.1, revenue is recognized when a good is “delivered” to the customer or a service has been performed. There is considerable discretion as to when the transaction is deemed to have taken place. It is easy to understand the incentives of salespeople who are struggling to meet internal targets toward the end of the fiscal period: To sell as much as possible as the period ends, e.g., by lowering credit standards or by moving sales from the next period to the current fiscal period. This latter option is acceptable as long as the sale has been made, i.e., the good has been delivered and/or the service has been provided. For companies that provide goods or services where it is sometimes difficult to assess the completion of the revenue-generating process (i.e., the delivery of the good or the provision of service), there is the potential for these companies to accelerate the recognition of revenue by reporting revenue in the current period that should be reported in a future period. Companies that provide goods and services as bundled products are a classic example where there may be opportunity for the acceleration of revenues. Consider a company selling computer software licenses with a multiperiod service agreement. The revenue associated with the provision of that service component of the software license should not be recognized at point of sale but at the time the service is provided to the customer. For example, consider a software provider that sells desktop applications in bulk to large corporations on 1 November 2007. This contract comes with built-in options to upgrade and extensive product support for the next two years. A determination needs to be made to allocate the revenue associated with this software sale over the 2007, 2008, and 2009 fiscal periods.

4.1.2.2. Warning Signs

The analyst needs to be particularly skeptical about revenue reporting practices when

- Top management has a significant portion of vested options in the money.

- The company is trying to maintain its track record of successively meeting analyst forecasts.

- The company is looking to raise additional financing.

These are risk factors in the sense of describing circumstances that can provide incentives for accelerating the recognition of revenue.

The warning signs for accelerated revenue are similar to what was described for over-stated revenue: Look for large positive changes in net accounts receivable and large decreases in unearned revenue accounts (to the extent these are separately disclosed). A large increase in accounts receivable could indicate credit sales made late in the fiscal period with associated deteriorations in credit quality. Large decreases in unearned revenue could be indicative of management’s aggressive determination that prior goods and services have been delivered/provided in the current fiscal period. Combining an analysis of the accrual activity in revenue-related accounts with the current market environment (e.g., pressing need to meet analyst forecasts or extensive outstanding vested options for top executives) can be an effective way to identify companies who have the incentive to be aggressive in the timing of revenue recognition and who have utilized accrual accounting choices to deliver revenue growth.

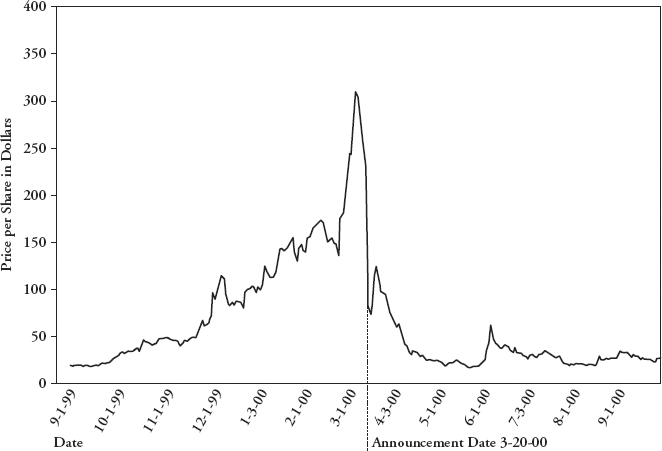

A good example is Microstrategy. Exhibit 16-10 outlines the evolution of Microstrategy’s stock price for the 1999–2000 period. Microstrategy announced that it would be restating its earnings in March 2000. They had accelerated the recognition of revenue by booking legitimate future sales orders in the current fiscal period. At first glance this does not seem particularly egregious: after all, these would have been legitimate sales. But placed in the context of significant capital market pressures, where analysts and investors generally were looking for exponential sales growth to support very lofty stock prices, the front-loading of revenues allowed Microstrategy to report very large revenue increases over the 1998–1999 period, fueling the stock price appreciation during 1999. When investors learned that this revenue growth was the result of front-loading future sales, there was a very quick correction in the market. There are numerous other cases of companies accelerating revenue recognition. A skeptical view on receivable growth and changes in unearned revenue, combined with an assessment of incentives to manipulate earnings, can help identify these companies before the stock price collapses.

EXHIBIT 16-10 Daily Stock Prices for Microstrategy 1 September 1999–29 September 2000

Note: Stock prices have been adjusted to account for the 26 January 2000 2:1 stock split.

Source: GAO (2002), Figure 18, based on the GAO’s analysis of NYSE TAQ data.

One way to detect acceleration of revenue recognition is to analyze the ratio of revenue to cash collected from customers. Cash collected from customers can be computed as revenue+decrease (minus increase) in accounts receivable+increase (minus decrease) in deferred income (or “deferred revenue”). In normal circumstances, the relation between revenue and cash collected from customers should be relatively stable. Large swings in revenue as a percent of cash collected from customers could occur for several reasons including the acceleration of revenue. Reported revenue as a percent of cash collected from customers would be expected to initially increase as the aggressive revenue recognition is adopted. Example 16-3 illustrates one technique of revenue acceleration: bill-and-hold sales.

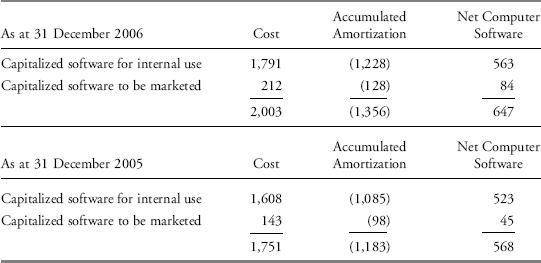

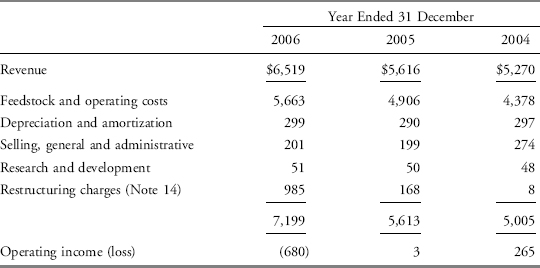

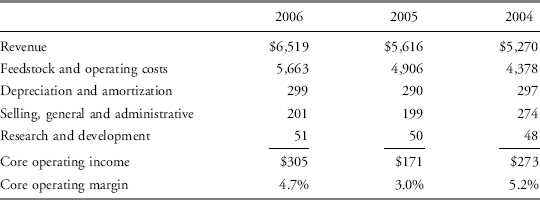

EXAMPLE 16-3 Revenue Recognition Practices

Diebold, Inc. (NYSE: DBD) is a leading manufacturer of Automated Teller Machines (ATMs) used in banks, as well as electronic voting machines. Certain of Diebold’s financial results for the years ended 31 December 2006, 2005 and 2004 are summarized as follows: