CHAPTER 10

LONG-LIVED ASSETS

After completing this reading, you will be able to do the following:

- Distinguish between costs that are capitalized and costs that are expensed in the period in which they are incurred.

- Compare the financial reporting of the following classifications of intangible assets: purchased, internally developed, acquired in a business combination.

- Explain and evaluate the effects on financial statements and ratios of capitalizing versus expensing costs in the period in which they are incurred.

- Describe the different depreciation methods for property, plant, and equipment and the effects of the choice of depreciation method and the assumptions concerning useful life and residual value on depreciation expense, financial statements, and ratios.

- Calculate depreciation expense.

- Describe the different amortization methods for intangible assets with finite lives and the effects of the choice of amortization method and the assumptions concerning useful life and residual value on amortization expense, financial statements, and ratios.

- Calculate amortization expense.

- Describe the revaluation model.

- Describe the impairment of property, plant, and equipment and intangible assets.

- Describe the derecognition of property, plant, and equipment and intangible assets.

- Explain and evaluate the effects on financial statements and ratios of impairment, revaluation, and derecognition of property, plant, and equipment and intangible assets.

- Describe the financial statement presentation of and disclosures relating to property, plant, and equipment and intangible assets.

- Analyze and interpret the financial statement disclosures regarding property, plant, and equipment and intangible assets.

- Compare the financial reporting of investment property with that of property, plant, and equipment.

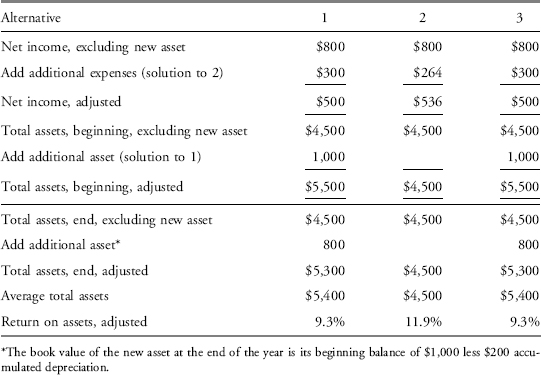

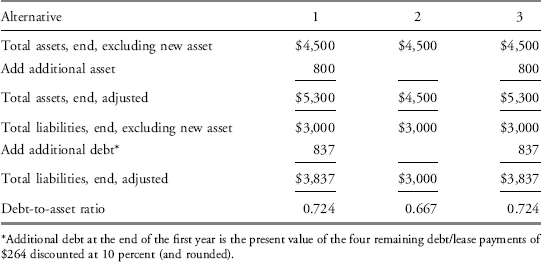

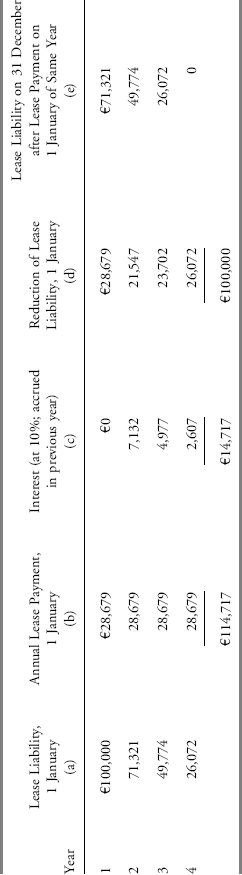

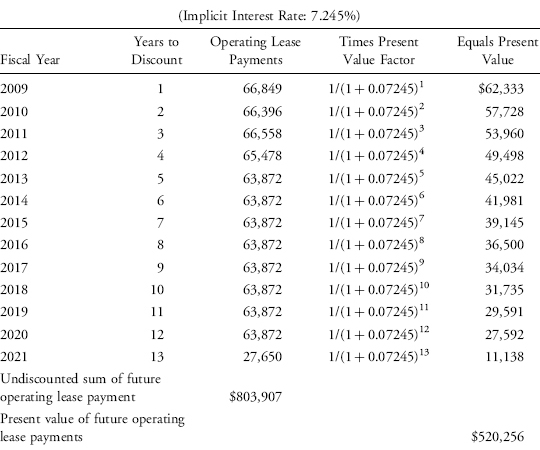

- Explain and evaluate the effects on financial statements and ratios of leasing assets instead of purchasing them.

- Explain and evaluate the effects on financial statements and ratios of finance leases and operating leases from the perspective of both the lessor and the lessee.

Long-lived assets, also referred to as noncurrent assets or long-term assets, are assets that are expected to provide economic benefits over a future period of time, typically greater than one year.1 Long-lived assets may be tangible, intangible, or financial assets. Examples of long-lived tangible assets, typically referred to as property, plant, and equipment and sometimes as fixed assets, include land, buildings, furniture and fixtures, machinery and equipment, and vehicles; examples of long-lived intangible assets (assets lacking physical substance) include patents and trademarks; and examples of long-lived financial assets include investments in equity or debt securities issued by other companies. The scope of this reading is limited to long-lived tangible and intangible assets (hereafter, referred to for simplicity as long-lived assets).

The first issue in accounting for a long-lived asset is determining its cost at acquisition. The second issue is how to allocate the cost to expense over time. The costs of most long-lived assets are capitalized and then allocated as expenses in the profit or loss (income) statement over the period of time during which they are expected to provide economic benefits. The two main types of long-lived assets with costs that are typically not allocated over time are land, which is not depreciated, and those intangible assets with indefinite useful lives. Additional issues that arise are the treatment of subsequent costs incurred related to the asset, the use of the cost model versus the revaluation model, unexpected declines in the value of the asset, classification of the asset with respect to intent (for example, held for use or held for sale), and the derecognition of the asset.

This reading is organized as follows. Section 2 describes and illustrates accounting for the acquisition of long-lived assets, with particular attention to the impact of capitalizing versus expensing expenditures. Section 3 describes the allocation of the costs of long-lived assets over their useful lives. Section 4 discusses the revaluation model that is based on changes in the fair value of an asset. Section 5 covers the concepts of impairment (unexpected decline in the value of an asset). Section 6 describes accounting for the derecognition of long-lived assets. Section 7 describes financial statement presentation, disclosures, and analysis of long-lived assets. Section 8 discusses differences in financial reporting of investment property compared with property, plant, and equipment. Section 9 describes accounting for leases. A summary is followed by practice problems.

2. ACQUISITION OF LONG-LIVED ASSETS

Upon acquisition, property, plant, and equipment (tangible assets with an economic life of longer than one year and intended to be held for the company’s own use) are recorded on the balance sheet at cost, which is typically the same as their fair value.2 Accounting for an intangible asset depends on how the asset is acquired. If several assets are acquired as part of a group, the purchase price is allocated to each asset on the basis of its fair value. An asset’s cost potentially includes expenditures additional to the purchase price.

A key concept in accounting for expenditures related to long-lived assets is whether and when such expenditures are capitalized (i.e., included in the asset shown on the balance sheet) versus expensed (i.e., treated as an expense of the period on the income statement). After examining the specific treatment of certain expenditures, we will consider the general financial statement impact of capitalizing versus expensing and two analytical issues related to the decision—namely, the effects on an individual company’s trend analysis and on comparability across companies.

2.1. Property, Plant, and Equipment

This section primarily discusses the accounting treatment for the acquisition of long-lived tangible assets (property, plant, and equipment) through purchase. Assets can be acquired by methods other than purchase.3 When an asset is exchanged for another asset, the asset acquired is recorded at fair value if reliable measures of fair value exist. Fair value is the fair value of the asset given up unless the fair value of the asset acquired is more clearly evident. If there is no reliable measure of fair value, the acquired asset is measured at the carrying amount of the asset given up. In this case, the carrying amount of the assets is unchanged, and no gain or loss is reported.

Typically, accounting for the exchange involves removing the carrying amount of the asset given up, adding a fair value for the asset acquired, and reporting any difference between the carrying amount and the fair value as a gain or loss. A gain would be reported when the fair value used for the newly acquired asset exceeds the carrying amount of the asset given up. A loss would be reported when the fair value used for the newly acquired asset is less than the carrying amount of the asset given up.

When property, plant, or equipment is purchased, the buyer records the asset at cost. In addition to the purchase price, the buyer also includes, as part of the cost of an asset, all the expenditures necessary to get the asset ready for its intended use. For example, freight costs borne by the purchaser to get the asset to the purchaser’s place of business and special installation and testing costs required to make the asset usable are included in the total cost of the asset.

Subsequent expenditures related to long-lived assets are included as part of the recorded value of the assets on the balance sheet (i.e., capitalized) if they are expected to provide benefits beyond one year in the future and are expensed if they are not expected to provide benefits in future periods. Expenditures that extend the original life of the asset are typically capitalized. Example 10-1 illustrates the difference between costs that are capitalized and costs that are expensed in a period.

EXAMPLE 10-1 Acquisition of PPE

Assume a (hypothetical) company, Trofferini S. A., incurred the following expenditures to purchase a towel and tissue roll machine: €10,900 purchase price including taxes, €200 for delivery of the machine, €300 for installation and testing of the machine, and €100 to train staff on maintaining the machine. In addition, the company paid a construction team €350 to reinforce the factory floor and ceiling joists to accommodate the machine’s weight. The company also paid €1,500 to repair the factory roof (a repair expected to extend the useful life of the factory by five years) and €1,000 to have the exterior of the factory and adjoining offices repainted for maintenance reasons. The repainting neither extends the life of factory and offices nor improves their usability.

1. Which of these expenditures will be capitalized and which will be expensed?

2. How will the treatment of these expenditures affect the company’s financial statements?

Solution to 1: The company will capitalize as part of the cost of the machine all costs that are necessary to get the new machine ready for its intended use: €10,900 purchase price, €200 for delivery, €300 for installation and testing, and €350 to reinforce the factory floor and ceiling joists to accommodate the machine’s weight (which was necessary to use the machine and does not increase the value of the factory). The €100 to train staff is not necessary to get the asset ready for its intended use and will be expensed.

The company will capitalize the expenditure of €1,500 to repair the factory roof because the repair is expected to extend the useful life of the factory. The company will expense the €1,000 to have the exterior of the factory and adjoining offices repainted because the painting does not extend the life or alter the productive capacity of the buildings.

Solution to 2: The costs related to the machine that are capitalized—€10,900 purchase price, €200 for delivery, €300 for installation and testing, and €350 to prepare the factory—will increase the carrying amount of the machine asset as shown on the balance sheet and will be included as investing cash outflows. The item related to the factory that is capitalized—the €1,500 roof repair—will increase the carrying amount of the factory asset as shown on the balance sheet and is an investing cash outflow. The expenditures of €100 to train staff and €1,000 to paint are expensed in the period and will reduce the amount of income reported on the company’s income statement (and thus reduce retained earnings on the balance sheet) and the operating cash flow.

Example 10-1 describes capitalizing versus expensing in the context of purchasing property, plant, and equipment. When a company constructs an asset (or acquires an asset that requires a long period of time to get ready for its intended use), borrowing costs incurred directly related to the construction are generally capitalized. Constructing a building, whether for sale (in which case, the building is classified as inventory) or for the company’s own use (in which case, the building is classified as a long-lived asset), typically requires a substantial amount of time. To finance construction, any borrowing costs incurred prior to the asset being ready for its intended use are capitalized as part of the cost of the asset. The company determines the interest rate to use on the basis of its existing borrowings or, if applicable, on a borrowing specifically incurred for constructing the asset. If a company takes out a loan specifically to construct a building, the interest cost on that loan during the time of construction would be capitalized as part of the building’s cost. Under IFRS, but not under U.S. GAAP, income earned on temporarily investing the borrowed monies decreases the amount of borrowing costs eligible for capitalization.

Thus, a company’s interest costs for a period are included either on the balance sheet (to the extent they are capitalized as part of an asset) or on the income statement (to the extent they are expensed). If the interest expenditure is incurred in connection with constructing an asset for the company’s own use, the capitalized interest appears on the balance sheet as a part of the relevant long-lived asset (i.e., property, plant, and equipment). The capitalized interest is expensed over time as the property is depreciated and is thus part of subsequent years’ depreciation expense rather than interest expense of the current period. If the interest expenditure is incurred in connection with constructing an asset to sell (for example, by a home builder), the capitalized interest appears on the company’s balance sheet as part of inventory. The capitalized interest is expensed as part of the cost of goods sold when the asset is sold. Interest payments made prior to completion of construction that are capitalized are classified as an investing cash outflow. Expensed interest may be classified as an operating or financing cash outflow under IFRS and is classified as an operating cash outflow under U.S. GAAP.

EXAMPLE 10-2 Capitalized Borrowing Costs

BILDA S. A., a hypothetical company, borrows €1,000,000 at an interest rate of 10 percent per year on 1 January 2010 to finance the construction of a factory that will have a useful life of 40 years. Construction is completed after two years, during which time the company earns €20,000 by temporarily investing the loan proceeds.

1. What is the amount of interest that will be capitalized under IFRS, and how would that amount differ from the amount that would be capitalized under U.S. GAAP?

2. Where will the capitalized borrowing cost appear on the company’s financial statements?

Solution to 1: The total amount of interest paid on the loan during construction is €200,000 (= €1,000,000 × 10% × 2 years). Under IFRS, the amount of borrowing cost eligible for capitalization is reduced by the €20,000 interest income from temporarily investing the loan proceeds, so the amount to be capitalized is €180,000. Under U.S. GAAP, the amount to be capitalized is €200,000.

Solution to 2: The capitalized borrowing costs will appear on the company’s balance sheet as a component of property, plant, and equipment. In the years prior to completion of construction, the interest paid will appear on the statement of cash flows as an investment activity. Over time, as the property is depreciated, the capitalized interest component is part of subsequent years’ depreciation expense on the company’s income statement.

2.2. Intangible Assets

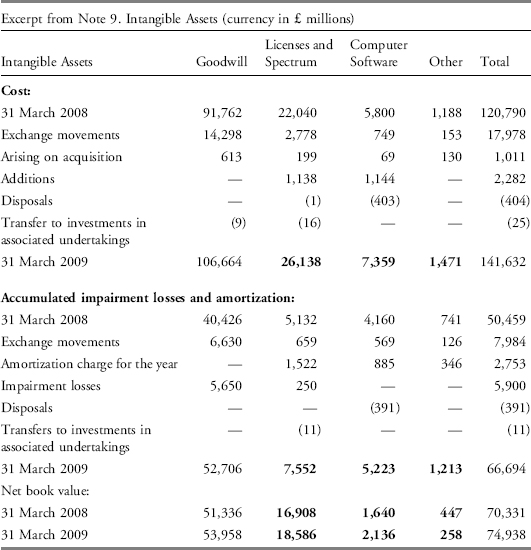

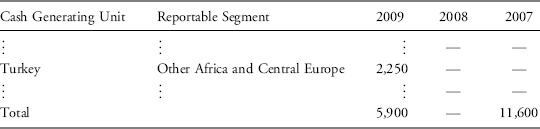

Intangible assets are assets lacking physical substance. Intangible assets include items that involve exclusive rights, such as patents, copyrights, trademarks, and franchises. Under IFRS, identifiable intangible assets must meet three definitional criteria. They must be (1) identifiable (either capable of being separated from the entity or arising from contractual or legal rights), (2) under the control of the company, and (3) expected to generate future economic benefits. In addition, two recognition criteria must be met: (1) It is probable that the expected future economic benefits of the asset will flow to the company, and (2) the cost of the asset can be reliably measured. Goodwill, which is not considered an identifiable intangible asset,4 arises when one company purchases another and the acquisition price exceeds the fair value of the identifiable assets (both the tangible assets and the identifiable intangible assets) acquired.

Accounting for an intangible asset depends on how it is acquired. The following sections describe accounting for intangible assets obtained in three ways: purchased in situations other than business combinations, developed internally, and acquired in business combinations.

2.2.1. Intangible Assets Purchased in Situations Other Than Business Combinations

Intangible assets purchased in situations other than business combinations, such as buying a patent, are treated at acquisition the same as long-lived tangible assets; they are recorded at their fair value when acquired, which is assumed to be equivalent to the purchase price. If several intangible assets are acquired as part of a group, the purchase price is allocated to each asset on the basis of its fair value.

In deciding how to treat individual intangible assets for analytical purposes, analysts are particularly aware that companies must use a substantial amount of judgment and numerous assumptions to determine the fair value of individual intangible assets. For analysis, therefore, understanding the types of intangible assets acquired can often be more useful than focusing on the values assigned to the individual assets. In other words, an analyst would typically be more interested in understanding what assets a company acquired (for example, franchise rights and a mailing list) than in the precise portion of the purchase price a company allocated to each asset. Understanding the types of assets a company acquires can offer insights into the company’s strategic direction and future operating potential.

2.2.2. Intangible Assets Developed Internally

In contrast with the treatment of construction costs of tangible assets, the costs to internally develop intangible assets are generally expensed when incurred. There are some situations, however, in which the costs incurred to internally develop an intangible asset are capitalized. The general analytical issues related to the capitalizing-versus-expensing decision apply here—namely, comparability across companies and the effect on an individual company’s trend analysis.

The general requirement that costs to internally develop intangible assets be expensed should be compared with capitalizing the cost of acquiring intangible assets in situations other than business combinations. Because costs associated with internally developing intangible assets are usually expensed, a company that has internally developed such intangible assets as patents, copyrights, or brands through expenditures on R&D or advertizing will recognize a lower amount of assets than a company that has obtained intangible assets through external purchase. In addition, on the statement of cash flows, costs of internally developing intangible assets are classified as operating cash outflows whereas costs of acquiring intangible assets are classified as investing cash outflows. Differences in strategy (developing versus acquiring intangible assets) can thus impact financial ratios.

IFRS require that expenditures on research (or during the research phase of an internal project) be expensed rather than capitalized as an intangible asset.5 Research is defined as “original and planned investigation undertaken with the prospect of gaining new scientific or technical knowledge and understanding.”6 The “research phase of an internal project” refers to the period during which a company cannot demonstrate that an intangible asset is being created—for example, the search for alternative materials or systems to use in a production process. IFRS allow companies to recognize an intangible asset arising from development (or the development phase of an internal project) if certain criteria are met, including a demonstration of the technical feasibility of completing the intangible asset and the intent to use or sell the asset. Development is defined as “the application of research findings or other knowledge to a plan or design for the production of new or substantially improved materials, devices, products, processes, systems or services before the start of commercial production or use.”7

Generally, U.S. GAAP require that both research and development costs be expensed as incurred but require capitalization of certain costs related to software development.8 Costs incurred to develop a software product for sale are expensed until the product’s technological feasibility is established and are capitalized thereafter. Similarly, companies expense costs related to the development of software for internal use until it is probable that the project will be completed and that the software will be used as intended. Thereafter, development costs are capitalized. The probability that the project will be completed is easier to demonstrate than is technological feasibility. The capitalized costs, related directly to developing software for sale or internal use, include the costs of employees who help build and test the software. The treatment of software development costs under U.S. GAAP is similar to the treatment of all costs of internally developed intangible assets under IFRS.

EXAMPLE 10-3 Software Development Costs

Assume REH AG, a hypothetical company, incurs expenditures of €1,000 per month during the fiscal year ended 31 December 2009 to develop software for internal use. Under IFRS, the company must treat the expenditures as an expense until the software meets the criteria for recognition as an intangible asset, after which time the expenditures can be capitalized as an intangible asset.

1. What is the accounting impact of the company being able to demonstrate that the software met the criteria for recognition as an intangible asset on 1 February versus 1 December?

2. How would the treatment of expenditures differ if the company reported under U.S. GAAP and it had established in 2008 that the project was likely to be completed?

Solution to 1: If the company is able to demonstrate that the software met the criteria for recognition as an intangible asset on 1 February, the company would recognize €1,000 of expense (on the income statement) during the fiscal year ended 31 December 2009. The other €11,000 of expenditures would be recognized as an intangible asset (on the balance sheet). Alternatively, if the company is not able to demonstrate that the software met the criteria for recognition as an intangible asset until 1 December, the company would recognize €11,000 of expense during the fiscal year ended 31 December 2009, with the other €1,000 of expenditures recognized as an intangible asset.

Solution to 2: Under U.S. GAAP, the company would capitalize the entire €12,000 spent to develop software for internal use.

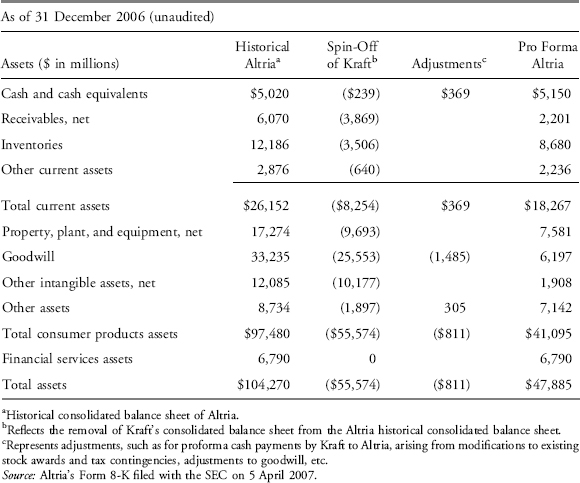

2.2.3. Intangible Assets Acquired in a Business Combination

When one company acquires another company, the transaction is accounted for using the acquisition method of accounting.9 Under the acquisition method, the company identified as the acquirer allocates the purchase price to each asset acquired (and each liability assumed) on the basis of its fair value. If the purchase price exceeds the sum of the amounts that can be allocated to individual identifiable assets and liabilities, the excess is recorded as goodwill. Goodwill cannot be identified separately from the business as a whole.

Under IFRS, the acquired individual assets include identifiable intangible assets that meet the definitional and recognition criteria.10 Otherwise, if the item is acquired in a business combination and cannot be recognized as a tangible or identifiable intangible asset, it is recognized as goodwill. Under U.S. GAAP, there are two criteria to judge whether an intangible asset acquired in a business combination should be recognized separately from goodwill: The asset must be either an item arising from contractual or legal rights or an item that can be separated from the acquired company. Examples of intangible assets treated separately from goodwill include the intangible assets previously mentioned that involve exclusive rights (patents, copyrights, franchises, licenses), as well as such items as internet domain names and video and audiovisual materials.

Exhibit 10-1 describes how InBev allocated the €40.3 billion purchase price for its acquisition of Anheuser-Busch. The majority of the identifiable intangible asset valuation (€16.473 billion) relates to brands with indefinite life. Another €256 million or €0.256 billion was for the identifiable intangible assets with definite useful lives—distribution agreements and favorable contracts. These assets are being amortized over the life of the associated contracts. In addition, €24.7 billion of goodwill was recognized.

EXHIBIT 10-1 Acquisition of Intangible Assets through a Business Combination

| Excerpt from the 2008 annual report of AB InBev (BRU: ABI): |

| On 18 November, InBev has completed the acquisition of Anheuser-Busch, following approval from shareholders of both companies.. . . Effective the date of the closing, InBev has changed its name to AB InBev to reflect the heritage and traditions of Anheuser-Busch. Under the terms of the merger agreement, all shares of Anheuser-Busch were acquired for 70 U.S. dollar per share in cash for an aggregate amount of approximately 52.5b U.S. dollar or 40.3b euro. |

| The transaction resulted in 24.7b euro goodwill provisionally allocated primarily to the U.S. business on the basis of expected synergies.. . . The valuation of the property, plant and equipment, intangible assets, investment in associates, interest bearing loans and borrowings and employee benefits is based on the valuation performed by independent valuation specialist. The other assets and liabilities are based on the current best estimates of AB InBev’s management. |

| The majority of the intangible asset valuation relates to brands with indefinite life. The valuation of the brands with indefinite life is based on a series of factors, including the brand history, the operating plan and the countries in which the brands are sold. The brands with indefinite life include the Budweiser family (including Bud and Bud Light), the Michelob brand family, the Busch brand family and the Natural brand family and have been fair valued for a total amount of 16,473m euro. Distribution agreements and favorable contracts have been fair valued for a total amount of 256m euro. These are being amortised over the term of the associated contracts ranging from 3 to 18 years. |

Source: AB InBev 2008 Annual Report, pp. 74–75.

2.3. Capitalizing versus Expensing—Impact on Financial Statements and Ratios

This section discusses the implications for financial statements and ratios of capitalizing versus expensing costs in the period in which they are incurred. We first summarize the general financial statement impact of capitalizing versus expensing and two analytical issues related to the decision—namely the effect on an individual company’s trend analysis and on comparability across companies.

In the period of the expenditure, an expenditure that is capitalized increases the amount of assets on the balance sheet and appears as an investing cash outflow on the statement of cash flows. In subsequent periods, a company allocates the capitalized amount over the asset’s useful life as depreciation or amortization expense (except assets that are not depreciated, i.e., land, or amortized, e.g., intangible assets with indefinite lives). This expense reduces net income on the income statement and reduces the value of the asset on the balance sheet. Depreciation and amortization are noncash expenses and therefore, apart from their effect on taxable income and taxes payable, have no impact on the cash flow statement. In the section of the statement of cash flows that reconciles net income to operating cash flow, depreciation and amortization expenses are added back to net income.

Alternatively, an expenditure that is expensed reduces net income by the after-tax amount of the expenditure in the period it is made. No asset is recorded on the balance sheet and thus no depreciation or amortization occurs in subsequent periods. The lower amount of net income is reflected in lower retained earnings on the balance sheet. An expenditure that is expensed appears as an operating cash outflow in the period it is made. There is no effect on the financial statements of subsequent periods.

Example 10-4 illustrates the impact on the financial statements of capitalizing versus expensing an expenditure.

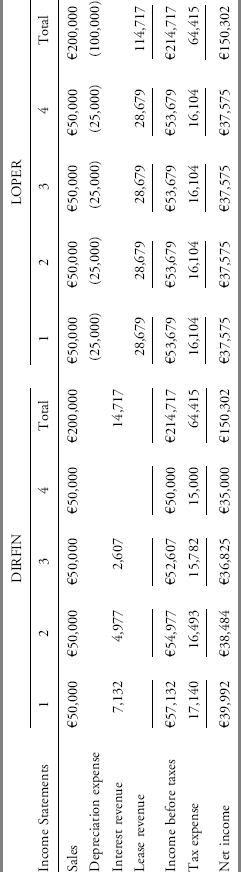

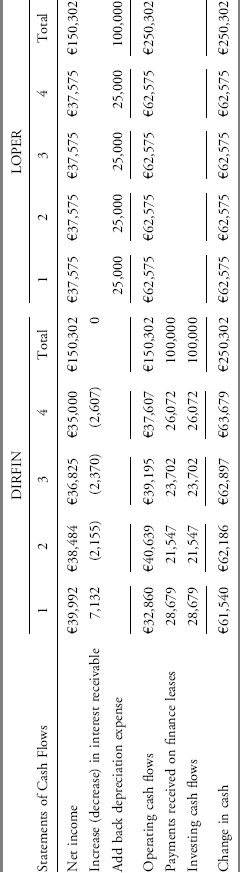

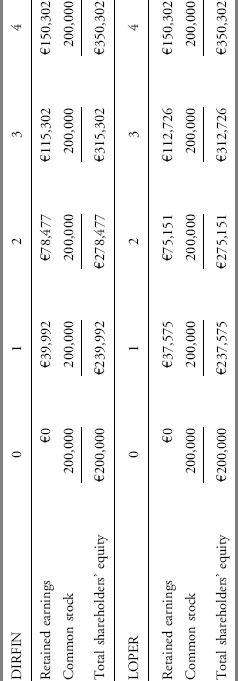

EXAMPLE 10-4 General Financial Statement Impact of Capitalizing versus Expensing

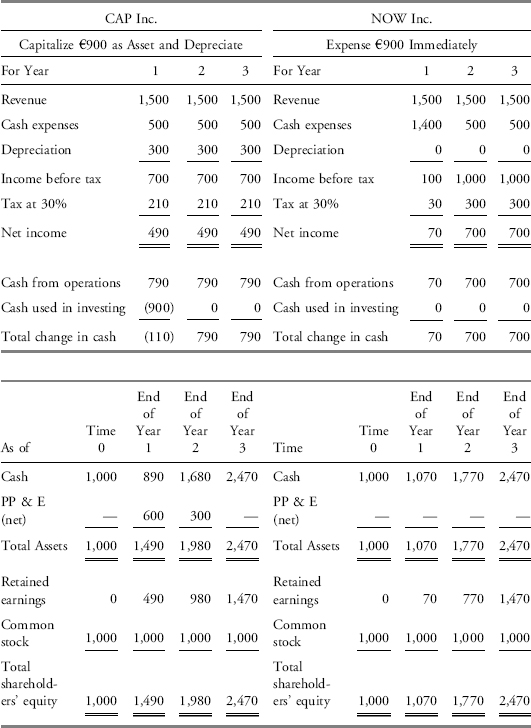

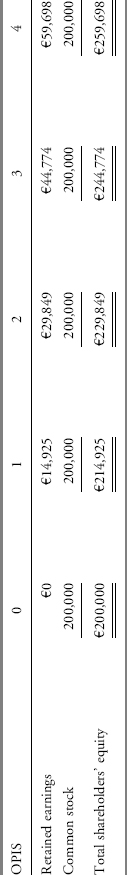

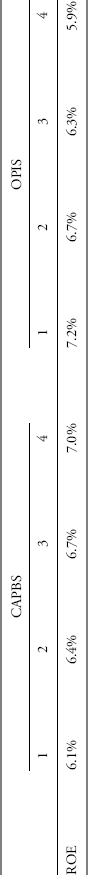

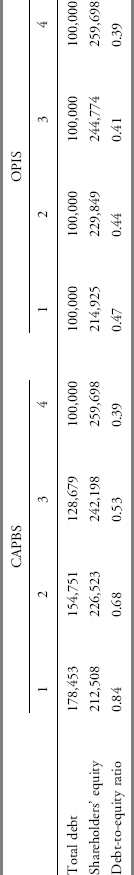

Assume two identical (hypothetical) companies, CAP Inc. (CAP) and NOW Inc. (NOW), start with €1,000 cash and €1,000 common stock. Each year the companies recognize total revenues of €1,500 cash and make cash expenditures, excluding an equipment purchase, of €500. At the beginning of operations, each company pays €900 to purchase equipment. CAP estimates the equipment will have a useful life of three years and an estimated salvage value of €0 at the end of the three years. NOW estimates a much shorter useful life and expenses the equipment immediately. The companies have no other assets and make no other asset purchases during the three-year period. Assume the companies pay no dividends, earn zero interest on cash balances, have a tax rate of 30 percent, and use the same accounting method for financial and tax purposes.

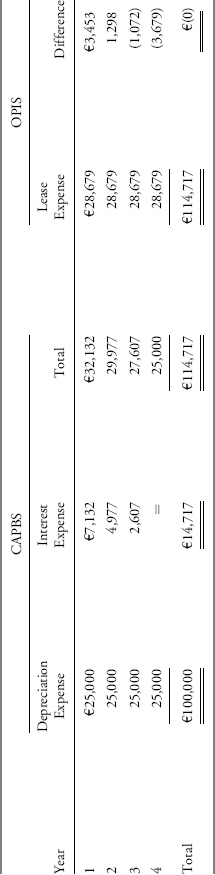

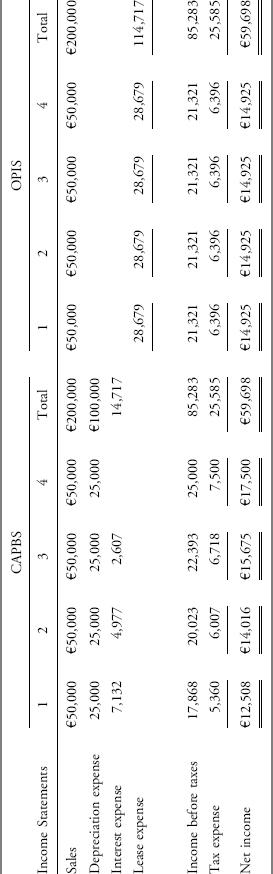

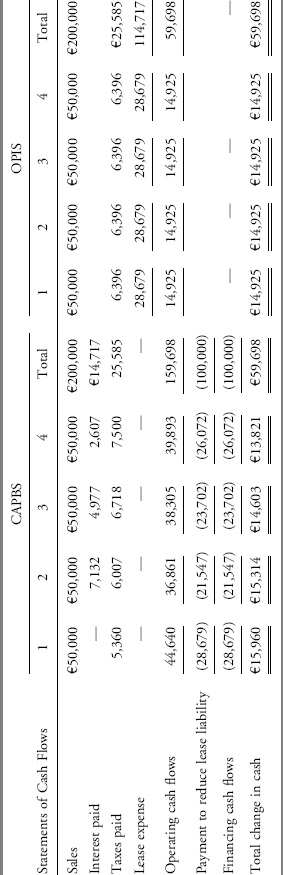

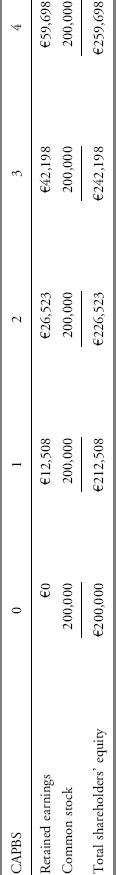

The left side of Exhibit 10-2 shows CAP’s financial statements; that is, with the expenditure capitalized and depreciated at €300 per year based on the straight-line method of depreciation (€900 cost minus €0 salvage value equals €900, divided by a three-year life equals €300 per year). The right side of the exhibit shows NOW’s financial statements, with the entire €900 expenditure treated as an expense in the first year. All amounts are in euro.

EXHIBIT 10-2 Capitalizing versus Expensing

1. Which company reports higher net income over the three years? Total cash flow? Cash from operations?

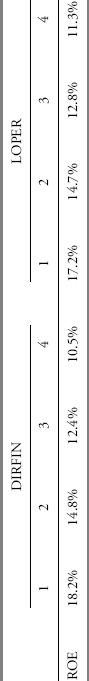

2. Based on ROE and net profit margin, how does the profitability of the two companies compare?

3. Why does NOW report change in cash of €70 in Year 1, while CAP reports total change in cash of (€110)?

Solution to 1: Neither company reports higher total net income or cash flow over the three years. The sum of net income over the three years is identical (€1,470 total) whether the €900 is capitalized or expensed. Also, the sum of the change in cash (€1,470 total) is identical under either scenario. CAP reports higher cash from operations by an amount of €900 because, under the capitalization scenario, the €900 purchase is treated as an investing cash flow.

Note: Because the companies use the same accounting method for both financial and taxable income, absent the assumption of zero interest on cash balances, expensing the €900 would have resulted in higher income and cash flow for NOW because the lower taxes paid in the first year (€30 versus €210) would have allowed NOW to earn interest income on the tax savings.

Solution to 2: In general, Ending shareholders’ equity = Beginning shareholders’ equity+Net income+Other comprehensive income − Dividends+Net capital contributions from shareholders. Because the companies in this example do not have other comprehensive income, did not pay dividends, and reported no capital contributions from shareholders, Ending retained earnings = Beginning retained earnings+Net income, and Ending shareholders’ equity = Beginning shareholders’ equity+Net income.

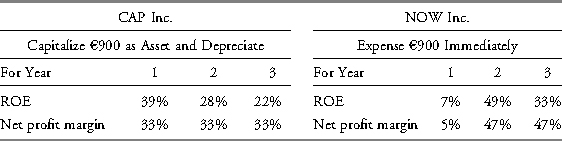

ROE is calculated as Net income divided by Average shareholders’ equity, and Net profit margin is calculated as Net income divided by Total revenue. For example, CAP had Year 1 ROE of 39 percent (€490/[(€1,000+€1,490)/2]), and Year 1 net profit margin of 33 percent (€490/€1,500).

As shown, capitalizing results in higher profitability ratios (ROE and net profit margin) in the first year, and lower profitability ratios in subsequent years. For example, CAP’s Year 1 ROE of 39 percent was higher than NOW’s Year 1 ROE of 7 percent, but in Years 2 and 3, NOW reports superior profitability.

Note also that NOW’s superior growth in net income between Year 1 and Year 2 is not attributable to superior performance compared to CAP but rather to the accounting decision to recognize the expense sooner than CAP. In general, all else equal, accounting decisions that result in recognizing expenses sooner will give the appearance of greater subsequent growth. Comparison of the growth of the two companies’ net incomes without an awareness of the difference in accounting methods would be misleading. As a corollary, NOW’s income and profitability exhibit greater volatility across the three years, not because of more volatile performance but rather because of the different accounting decision.

Solution to 3: NOW reports an increase in cash of €70 in Year 1, while CAP reports a decrease in cash of €110 because NOW’s taxes were €180 lower than CAP’s taxes (€30 versus €210).

Note that this problem assumes the accounting method used by each company for its tax purposes is identical to the accounting method used by the company for its financial reporting. In many countries, companies are allowed to use different depreciation methods for financial reporting and taxes, which may give rise to deferred taxes.

As shown, discretion regarding whether to expense or capitalize expenditures can impede comparability across companies. Example 10-4 assumes the companies purchase a single asset in one year. Because the sum of net income over the three-year period is identical whether the asset is capitalized or expensed, it illustrates that although capitalizing results in higher profitability compared to expensing in the first year, it results in lower profitability ratios in the subsequent years. Conversely, expensing results in lower profitability in the first year but higher profitability in later years, indicating a favorable trend.

Similarly, shareholders’ equity for a company that capitalizes the expenditure will be higher in the early years because the initially higher profits result in initially higher retained earnings. Example 10-4 assumes the companies purchase a single asset in one year and report identical amounts of total net income over the three-year period, so shareholders’ equity (and retained earnings) for the firm that expenses will be identical to shareholders’ equity (and retained earnings) for the capitalizing firm at the end of the three-year period.

Although Example 10-4 shows companies purchasing an asset only in the first year, if a company continues to purchase similar or increasing amounts of assets each year, the profitability-enhancing effect of capitalizing continues if the amount of the expenditures in a period continues to be more than the depreciation expense. Example 10-5 illustrates this point.

EXAMPLE 10-5 Impact of Capitalizing versus Expensing for Ongoing Purchases

A company buys a £300 computer in Year 1 and capitalizes the expenditure. The computer has a useful life of three years and an expected salvage value of £0, so the annual depreciation expense using the straight-line method is £100 per year. Compared to expensing the entire £300 immediately, the company’s pretax profit in Year 1 is £200 greater.

1. Assume that the company continues to buy an identical computer each year at the same price. If the company uses the same accounting treatment for each of the computers, when does the profit-enhancing effect of capitalizing versus expensing end?

2. If the company buys another identical computer in Year 4, using the same accounting treatment as the prior years, what is the effect on Year 4 profits of capitalizing versus expensing these expenditures?

Solution to 1: The profit-enhancing effect of capitalizing versus expensing would end in Year 3. In Year 3, the depreciation expense on each of the three computers bought in Years 1, 2, and 3 would total £300 (£100+£100+£100). Therefore, the total depreciation expense for Year 3 will be exactly equal to the capital expenditure in Year 3. The expense in Year 3 would be £300, regardless of whether the company capitalized or expensed the annual computer purchases.

Solution to 2: There is no impact on Year 4 profits. As in the previous year, the depreciation expense on each of the three computers bought in Years 2, 3, and 4 would total £300 (£100+£100+£100). Therefore, the total depreciation expense for Year 4 will be exactly equal to the capital expenditure in Year 4. Pretax profits would be reduced by £300, regardless of whether the company capitalized or expensed the annual computer purchases.

Compared to expensing an expenditure, capitalizing the expenditure typically results in greater amounts reported as cash from operations. Capitalized expenditures are typically treated as an investment cash outflow whereas expenses reduce operating cash flows. Because cash flow from operating activities is an important consideration in some valuation models, companies may try to maximize reported cash flow from operations by capitalizing expenditures that should be expensed. Valuation models that use free cash flow will consider not only operating cash flows but also investing cash flows. Analysts should be alert to evidence of companies manipulating reported cash flow from operations by capitalizing expenditures that should be expensed.

In summary, holding all else constant, capitalizing an expenditure enhances current profitability and increases reported cash flow from operations. The profitability-enhancing effect of capitalizing continues so long as capital expenditures exceed the depreciation expense. Profitability-enhancing motivations for decisions to capitalize should be considered when analyzing performance. For example, a company may choose to capitalize more expenditures (within the allowable bounds of accounting standards) to achieve earnings targets for a given period. Expensing a cost in the period reduces current period profits but enhances future profitability and thus enhances the profit trend. Profit trend-enhancing motivations should also be considered when analyzing performance. If the company is in a reporting environment which requires identical accounting methods for financial reporting and taxes (unlike the United States, which permits companies to use depreciation methods for reporting purposes that differ from the depreciation method required by tax purposes), then expensing will have a more favorable cash flow impact because paying lower taxes in an earlier period creates an opportunity to earn interest income on the cash saved.

In contrast with the relatively simple examples given previously, it is generally neither possible nor desirable to identify individual instances involving discretion about whether to capitalize or expense expenditures. An analyst can, however, typically identify significant items of expenditure treated differently across companies. The items of expenditure giving rise to the most relevant differences across companies will vary by industry. This cross-industry variation is apparent in the following discussion of the capitalization of expenditures.

2.4. Capitalization of Interest Costs

As noted earlier, companies generally must capitalize interest costs associated with acquiring or constructing an asset that requires a long period of time to get ready for its intended use.11 As a consequence of this accounting treatment, a company’s interest costs for a period can appear either on the balance sheet (to the extent they are capitalized) or on the income statement (to the extent they are expensed).

If the interest expenditure is incurred in connection with constructing an asset for the company’s own use, the capitalized interest appears on the balance sheet as a part of the relevant long-lived asset. The capitalized interest is expensed over time as the property is depreciated—and is thus part of depreciation expense rather than interest expense. If the interest expenditure is incurred in connection with constructing an asset to sell, for example by a real estate construction company, the capitalized interest appears on the company’s balance sheet as part of inventory. The capitalized interest is then expensed as part of the cost of sales when the asset is sold.

The treatment of capitalized interest poses certain issues that analysts should consider. First, capitalized interest appears as part of investing cash outflows, whereas expensed interest reduces operating cash flow. Although the treatment is consistent with accounting standards, an analyst may want to examine the impact on reported cash flows. Second, interest coverage ratios are solvency indicators measuring the extent to which a company’s earnings (or cash flow) in a period covered its interest costs. To provide a true picture of a company’s interest coverage, the entire amount of interest expenditure, both the capitalized portion and the expensed portion, should be used in calculating interest coverage ratios. Additionally, if a company is depreciating interest that it capitalized in a previous period, income should be adjusted to eliminate the effect of that depreciation. Example 10-6 illustrates the calculation.

EXAMPLE 10-6 Effect of Capitalized Interest Costs on Coverage Ratios and Cash Flow

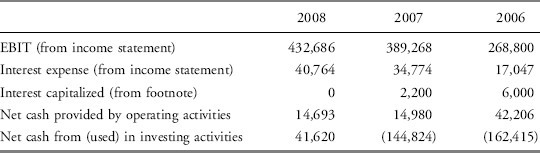

MTR Gaming Group, Inc. (NasdaqGS: MNTG) disclosed the following information in one of the footnotes to its financial statements: “Interest is allocated and capitalized to construction in progress by applying our cost of borrowing rate to qualifying assets. Interest capitalized in 2007 and 2006 was $2.2 million and $6.0 million, respectively. There was no interest capitalized during 2008.”(Form 10-K filed 13 March 2009).

EXHIBIT 10-3 MTR Gaming Group Selected Data, as Reported (dollars in thousands)

1. Calculate and interpret MTR’s interest coverage ratio with and without capitalized interest. Assume that capitalized interest increases depreciation expense by $475 thousand in 2008 and 2007, and by $365 thousand in 2006.

2. Calculate MTR’s percentage change in operating cash flow from 2006 to 2007 and from 2007 to 2008. Assuming the financial reporting does not affect reporting for income taxes, what were the effects of capitalized interest on operating and investing cash flows?

Solution to 1: MTR did not capitalize any interest during 2008, so the interest coverage ratio for this year is affected only by depreciation expense related to previously capitalized interest. The interest coverage ratio, measured as earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT) divided by interest expense, was as follows for 2008:

10.61 ($432,686 ÷ $40,764) for 2008 without adjusting for capitalized interest

10.63 [($432,686+ $475)÷ $40,764] including an adjustment to EBIT for depreciation of previously capitalized interest

For the years 2007 and 2006, interest coverage ratios with and without capitalized interest were as follows:

For 2007

11.19 ($389,268÷ $34,774) without adjusting for capitalized interest; and

10.54 [($389,268+$475) ÷($34,774+$2,200)] including an adjustment to EBIT for depreciation of previously capitalized interest and an adjustment to interest expense for the amount of interest capitalized in 2007.

For 2006

15.77 ($268,800÷ $17,047) without adjusting for capitalized interest; and

11.68 [($268,800+$365) ÷ ($17,047+$6,000)] including an adjustment to EBIT for depreciation of previously capitalized interest and an adjustment to interest expense for the amount of interest capitalized in 2006.

Because MTR capitalizes interest in previous years, EBIT is adjusted by adding in depreciation expense due to capitalized interest costs.

The earlier calculations indicate that MTR’s interest coverage deteriorated over the three-year period from 2006 to 2008, even with no adjustments for capitalized interest. In both 2006 and 2007, the coverage ratio is lower when adjusted for capitalized interest. For 2006, the interest coverage ratio of 11.68 that includes capitalized interest is substantially lower than the ratio without capitalized interest.

Solution to 2: If the interest had been expensed rather than capitalized, operating cash flows would have been substantially lower in 2006, slightly lower in 2007, but unchanged in 2008. If the interest had been expensed rather than capitalized, the trend—at least in the last two years—would have been more favorable; operating cash flows would have increased rather than decreased over the 2007 to 2008 period. On an unadjusted basis, for 2008 compared with 2007, MTR’s operating cash flow declined by 1.9 percent [($14,693÷ $14,980) − 1]. If the $2,200 of interest had been expensed rather than capitalized in 2007, the change in operating cash flow would have been positive, 15.0 percent {[$14,693 ÷ ($14,980 − $2,200)] − 1}.

If interest had been expensed rather than capitalized, the amount of cash outflow for investing activities would have been lower in 2006 and 2007 but unaffected in 2008. The percentage decline in cash outflows for investing activities from 2006 to 2007 would have been slightly smaller excluding capitalized interest from investing activities, 8.8 percent {[($144,824 − $2,200) ÷ ($162,415 − $6,000)] − 1}.

The treatment of capitalized interest raises issues for consideration by an analyst. First, capitalized interest appears as part of investing cash outflows, whereas expensed interest reduces operating or financing cash flow under IFRS and operating cash flow under U.S. GAAP. An analyst may want to examine the impact on reported cash flows of interest expenditures when comparing companies. Second, interest coverage ratios are solvency indicators measuring the extent to which a company’s earnings (or cash flow) in a period covered its interest costs. To provide a true picture of a company’s interest coverage, the entire amount of interest, both the capitalized portion and the expensed portion, should be used in calculating interest coverage ratios.

Generally, including capitalized interest in the calculation of interest coverage ratios provides a better assessment of a company’s solvency. In assigning credit ratings, rating agencies include capitalized interest in coverage ratios. For example, Standard & Poor’s calculates the EBIT interest coverage ratio as EBIT divided by gross interest (defined as interest prior to deductions for capitalized interest or interest income).

Maintaining a minimum interest coverage ratio is a financial covenant often included in lending agreements, for example, bank loans and bond indentures. The definition of the coverage ratio can be found in the company’s credit agreement. The definition is relevant because treatment of capitalized interest in calculating coverage ratios would affect an assessment of how close a company’s actual ratios are to the levels specified by its financial covenants and thus the probability of breaching those covenants.

2.5. Capitalization of Internal Development Costs

As noted previously, accounting standards require companies to capitalize software development costs after a product’s feasibility is established. Despite this requirement, judgment in determining feasibility means that companies’ capitalization practices may differ. For example, as illustrated in Exhibit 10-4, Microsoft judges product feasibility to be established very shortly before manufacturing begins and, therefore, effectively expenses—rather than capitalizes—research and development costs.

EXHIBIT 10-4 Disclosure on Software Development Costs

| Excerpt from Management’s Discussion and Analysis (MD&A) of Microsoft Corporation (NasdaqGS: MSFT), Application of Critical Accounting Policies, Research and Development Costs: |

| SFAS No.86 specifies that costs incurred internally in researching and developing a computer software product should be charged to expense until technological feasibility has been established for the product. Once technological feasibility is established, all software costs should be capitalized until the product is available for general release to customers. Judgment is required in determining when technological feasibility of a product is established. We have determined that technological feasibility for our software products is reached after all high-risk development issues have been resolved through coding and testing. Generally, this occurs shortly before the products are released to manufacturing. The amortization of these costs is included in cost of revenue over the estimated life of the products. |

Source: Microsoft Corporation Annual Report 2009, p. 36.

Expensing rather than capitalizing development costs results in lower net income in the current period. Expensing rather than capitalizing will continue to result in lower net income so long as the amount of the current-period development expenses is higher than the amortization expense that would have resulted from amortizing prior periods’ capitalized development costs—the typical situation when a company’s development costs are increasing. On the statement of cash flows, expensing rather than capitalizing development costs results in lower net operating cash flows and higher net investing cash flows. This is because the development costs are reflected as operating cash outflows rather than investing cash outflows.

In comparing the financial performance of a company that expenses most or all software development costs, such as Microsoft, with another company that capitalizes software development costs, adjustments can be made to make the two comparable. For the company that capitalizes software development costs, an analyst can adjust (a) the income statement to include software development costs as an expense and to exclude amortization of prior years’ software development costs; (b) the balance sheet to exclude capitalized software (decrease assets and equity); and (c) the statement of cash flows to decrease operating cash flows and decrease cash used in investing by the amount of the current period development costs. Any ratios that include income, long-lived assets, or cash flow from operations—such as return on equity—will also be affected.

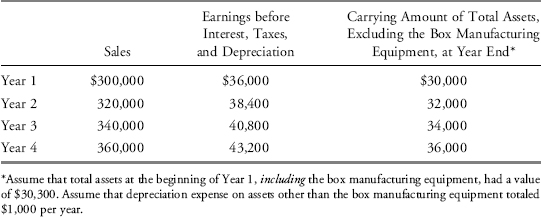

EXAMPLE 10-7 Software Development Costs

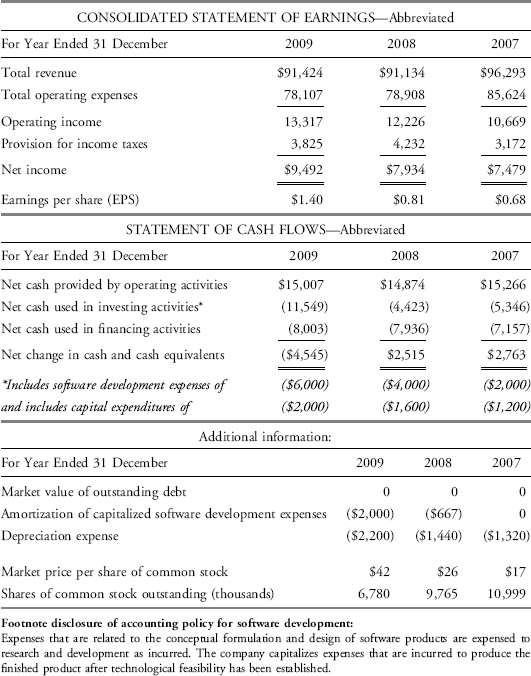

You are working on a project involving the analysis of JHH Software, a (hypothetical) software development company that established technical feasibility for its first product in 2007. Part of your analysis involves computing certain market-based ratios, which you will use to compare JHH to another company that expenses all of its software development expenditures. Relevant data and excerpts from the company’s annual report are included in Exhibit 10-5.

EXHIBIT 10-5 JHH SOFTWARE (dollars in thousands, except per-share amounts)

1. Compute the following ratios for JHH based on the reported financial statements for fiscal year ended 31 December 2009, with no adjustments. Next, determine the approximate impact on these ratios if the company had expensed rather than capitalized its investments in software. (Assume the financial reporting does not affect reporting for income taxes. There would be no change in the effective tax rate.)

A. P/E: Price/Earnings per share

B. P/CFO: Price/Operating cash flow per share

C. EV/EBITDA: Enterprise value/EBITDA, where enterprise value is defined as the total market value of all sources of a company’s financing, including equity and debt, and EBITDA is earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization.

2. Interpret the changes in the ratios.

Solution to 1: (Dollars are in thousands, except per-share amounts.) JHH’s 2009 ratios are presented in the following table:

A. Based on the information as reported, the P/E ratio was 30.0 ($42 ÷ $1.40). Based on EPS adjusted to expense software development costs, the P/E ratio was 42.9 ($42 ÷ $0.98).

- Price: Assuming that the market value of the company’s equity is based on its fundamentals, the price per share is $42, regardless of a difference in accounting.

- EPS: As reported, EPS was $1.40. Adjusted EPS was $0.98. Expensing software development costs would have reduced JHH’s 2009 operating income by $6,000, but the company would have reported no amortization of prior years’ software costs, which would have increased operating income by $2,000. The net change of $4,000 would have reduced operating income from the reported $13,317 to $9,317. The effective tax rate for 2009 ($3,825 ÷ $13,317) is 28.72%, and using this effective tax rate would give an adjusted net income of $6,641 [$9,317 × (1 − 0.2872)], compared to $9,492 before the adjustment. The EPS would therefore be reduced from the reported $1.40 to $0.98 (adjusted net income of $6,641 divided by 6,780 shares).

B. Based on information as reported, the P/CFO was 19.0 ($42 ÷ $2.21). Based on CFO adjusted to expense software development costs, the P/CFO was 31.6 ($42 ÷ $1.33).

- Price: Assuming that the market value of the company’s equity is based on its fundamentals, the price per share is $42, regardless of a difference in accounting.

- CFO per share, as reported, was $2.21 (total operating cash flows $15,007 ÷y 6,780 shares).

- CFO per share, as adjusted, was $1.33. The company’s $6,000 expenditure on software development costs was reported as a cash outflow from investing activities, so expensing those costs would reduce cash from operating activities by $6,000, from the reported $15,007 to $9,007. Dividing adjusted total operating cash flow of $9,007 by 6,780 shares results in cash flow per share of $1.33.

C. Based on information as reported, the EV/EBITDA was 16.3 ($284,760 ÷ $17,517). Based on EBITDA adjusted to expense software development costs, the EV/EBITDA was 24.7 ($284,760 ÷ $11,517).

- Enterprise Value: Enterprise value is the sum of the market value of the company’s equity and debt. JHH has no debt, and therefore the enterprise value is equal to the market value of its equity. The market value of its equity is $284,760 ($42 per share × 6,780 shares).

- EBITDA, as reported, was $17,517 (earnings before interest and taxes of $13,317 plus $2,200 depreciation plus $2,000 amortization).

- EBITDA, adjusted for expensing software development costs by the inclusion of $6,000 development expense and the exclusion of $2,000 amortization of prior expense, would be $11,517 (earnings before interest and taxes of $9,317 plus $2,200 depreciation plus $0 amortization).

Solution to 2: Expensing software development costs would decrease historical profits, operating cash flow, and EBITDA, and would thus increase all market multiples. So JHH’s stock would appear more expensive if it expensed rather than capitalized the software development costs.

If the unadjusted market-based ratios were used in the comparison of JHH to its competitor that expenses all software development expenditures, then JHH might appear to be underpriced when the difference is solely related to accounting factors. JHH’s adjusted market-based ratios provide a better basis for comparison.

For the company in Example 10-7, current period software development expenditures exceed the amortization of prior periods’ capitalized software development expenditures. As a result, expensing rather than capitalizing software development costs would have the effect of lowering income. If, however, software development expenditures slowed such that current expenditures were lower than the amortization of prior periods’ capitalized software development expenditures, then expensing software development costs would have the effect of increasing income relative to capitalizing it.

This section illustrated how decisions about capitalizing versus expensing impact financial statements and ratios. Earlier expensing lowers current profits but enhances trends, whereas capitalizing now and expensing later enhances current profits. Having described the accounting for acquisition of long-lived assets, we now turn to the topic of measuring long-lived assets in subsequent periods.

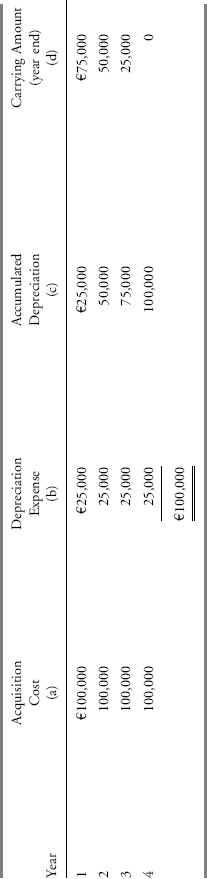

3. DEPRECIATION AND AMORTIZATION OF LONG-LIVED ASSETS

Under the cost model of reporting long-lived assets, which is permitted under IFRS and required under U.S. GAAP, the capitalized costs of long-lived tangible assets (other than land, which is not depreciated) and intangible assets with finite useful lives are allocated to subsequent periods as depreciation and amortization expenses. Depreciation and amortization are effectively the same concept, with the term depreciation referring to the process of allocating tangible assets’ costs and the term amortization referring to the process of allocating intangible assets’ costs.12 The alternative model of reporting long-lived assets is the revaluation model, which is permitted under IFRS but not under U.S. GAAP. Under the revaluation model, a company reports the long-lived asset at fair value rather than at acquisition cost (historical cost) less accumulated depreciation or amortization, as in the cost model.

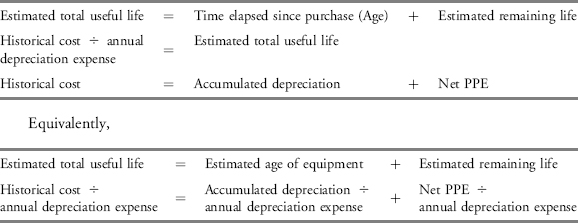

An asset’s carrying amount is the amount at which the asset is reported on the balance sheet. Under the cost model, at any point in time, the carrying amount (also called carrying value or net book value) of a long-lived asset is equal to its historical cost minus the amount of depreciation or amortization that has been accumulated since the asset’s purchase (assuming that the asset has not been impaired, a topic which will be addressed in Section 5). Companies may present on the balance sheet the total net amount of property, plant, and equipment and the total net amount of intangible assets. However, more detail is disclosed in the notes to financial statements. The details disclosed typically include the acquisition costs, the depreciation and amortization expenses, the accumulated depreciation and amortization amounts, the depreciation and amortization methods used, and information on the assumptions used to depreciate and amortize long-lived assets.

3.1. Depreciation Methods and Calculation of Depreciation Expense

Depreciation methods include the straight-line method, in which the cost of an asset is allocated to expense evenly over its useful life; accelerated methods, in which the allocation of cost is greater in earlier years; and the units-of-production method, in which the allocation of cost corresponds to the actual use of an asset in a particular period. The choice of depreciation method affects the amounts reported on the financial statements, including the amounts for reported assets and operating and net income. This, in turn, affects a variety of financial ratios, including fixed asset turnover, total asset turnover, operating profit margin, operating return on assets, and return on assets.

Using the straight-line method, depreciation expense is calculated as depreciable cost divided by estimated useful life and is the same for each period. Depreciable cost is the historical cost of the tangible asset minus the estimated residual (salvage) value.13 A commonly used accelerated method is the declining balance method, in which the amount of depreciation expense for a period is calculated as some percentage of the carrying amount (i.e., cost net of accumulated depreciation at the beginning of the period). When an accelerated method is used, depreciable cost is not used to calculate the depreciation expense but the carrying amount should not be reduced below the estimated residual value. In the units-of-production method, the amount of depreciation expense for a period is based on the proportion of the asset’s production during the period compared with the total estimated productive capacity of the asset over its useful life. The depreciation expense is calculated as depreciable cost times production in the period divided by estimated productive capacity over the life of the asset. Equivalently, the company may estimate a depreciation cost per unit (depreciable cost divided by estimated productive capacity) and calculate depreciation expense as depreciation cost per unit times production in the period. Regardless of the depreciation method used, the carrying amount of the asset is not reduced below the estimated residual value. Example 10-8 provides an example of these depreciation methods.

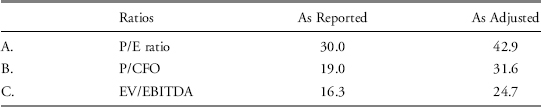

EXAMPLE 10-8 Alternative Depreciation Methods

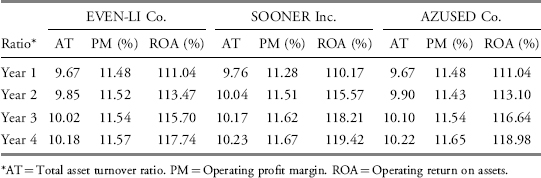

You are analyzing three hypothetical companies: EVEN-LI Co., SOONER Inc., and AZUSED Co. At the beginning of Year 1, each company buys an identical piece of box manufacturing equipment for $2,300 and has the same assumptions about useful life, estimated residual value, and productive capacity. The annual production of each company is the same, but each company uses a different method of depreciation. As disclosed in each company’s notes to the financial statements, each company’s depreciation method, assumptions, and production are as follows:

Depreciation method

- EVEN-LI Co.: straight-line method

- SOONER Inc.: double-declining balance method (the rate applied to the carrying amount is double the depreciation rate for the straight-line method)

- AZUSED Co.: units-of-production method

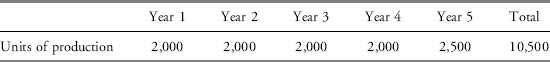

Assumptions and production

- Estimated residual value: $100

- Estimated useful life: 4 years

- Total estimated productive capacity: 800 boxes

- Production in each of the four years: 200 boxes in the first year, 300 in the second year, 200 in the third year, and 100 in the fourth year

1. Using the following template for each company, record its beginning and ending net book value (carrying amount), end-of-year accumulated depreciation, and annual depreciation expense for the box manufacturing equipment.

Template:

2. Explain the significant differences in the timing of the recognition of the depreciation expense.

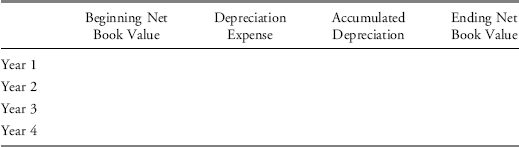

3. For each company, assume that sales, earnings before interest, taxes, and depreciation, and assets other than the box manufacturing equipment are as shown in the following table. Calculate the total asset turnover ratio, the operating profit margin, and the operating return on assets for each company for each of the four years. Discuss the ratios, comparing results within and across companies.

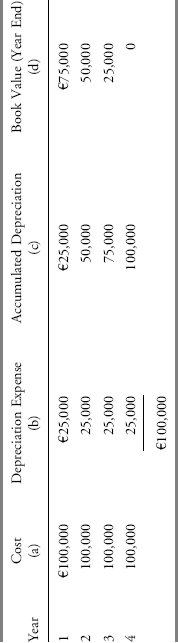

Solution to 1: For each company, the following information applies: Beginning net book value in Year 1 equals the purchase price of $2,300; accumulated year-end depreciation equals the balance from the previous year plus the current year’s depreciation expense; ending net book value (carrying amount) equals original cost minus accumulated year-end depreciation (which is the same as beginning net book value minus depreciation expense); and beginning net book value in Years 2, 3, and 4 equals the ending net book value of the prior year. The following text and filled-in templates describe how depreciation expense is calculated for each company.

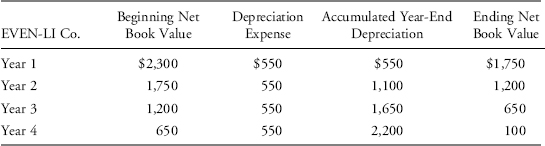

EVEN-LI Co. uses the straight-line method, so depreciation expense in each year equals $550, which is calculated as ($2,300 original cost − $100 residual value)/4 years. The net book value at the end of Year 4 is the estimated residual value of $100.

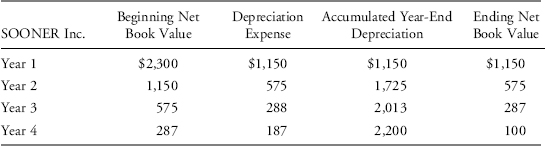

SOONER Inc. uses the double-declining balance method. The depreciation rate for the double-declining balance method is double the depreciation rate for the straight-line method. The depreciation rate under the straight-line method is 25 percent (100 percent divided by 4 years). Thus, the depreciation rate for the double-declining balance method is 50 percent (2 times 25 percent). The depreciation expense for the first year is $1,150 (50 percent of $2,300). Note that under this method, the depreciation rate of 50 percent is applied to the carrying amount (net book value) of the asset, without adjustment for expected residual value. Because the carrying amount of the asset is not depreciated below its estimated residual value, however, the depreciation expense in the final year of depreciation decreases the ending net book value (carrying amount) to the estimated residual value.

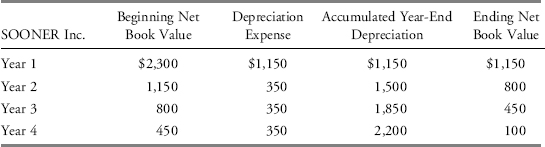

Another common approach (not required in this question) is to use an accelerated method, such as the double-declining method, for some period (a year or more) and then to change to the straight-line method for the remaining life of the asset. If SOONER had used the double-declining method for the first year and then switched to the straight-line method for Years 2, 3, and 4, the depreciation expense would be $350 [($1,150 − $100 estimated residual value)/3 years] a year for Years 2, 3, and 4. The results for SOONER under this alternative approach are shown here.

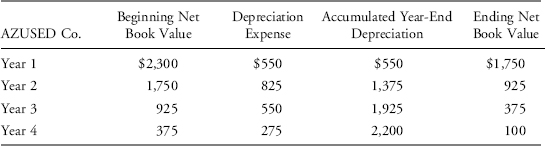

AZUSED Co. uses the units-of-production method. Dividing the equipment’s total depreciable cost by its total productive capacity gives a cost per unit of $2.75, calculated as ($2,300 original cost − $100 residual value)/800. The depreciation expense recognized each year is the number of units produced times $2.75. For Year 1, the amount of depreciation expense is $550 (200 units times $2.75). For Year 2, the amount is $825 (300 units times $2.75). For Year 3, the amount is $550. For Year 4, the amount is $275.

Solution to 2: All three methods result in the same total amount of accumulated depreciation over the life of the equipment. The significant differences are simply in the timing of the recognition of the depreciation expense. The straight-line method recognizes the expense evenly, the accelerated method recognizes most of the expense in the first year, and the units-of-production method recognizes the expense on the basis of production (or use of the asset). Under all three methods, the ending net book value is $100.

Solution to 3:

Total asset turnover ratio = Total revenue ÷ Average total assets

Operating profit margin = Earnings before interest and taxes ÷ Total revenue

Operating return on assets = Earnings before interest and taxes ÷ Average total assets

Ratios are shown in the table following, and details of the calculations for Years 1 and 2 are described after discussion of the ratios.

For all companies, the asset turnover ratio increased over time because sales grew at a faster rate than that of the assets. SOONER had consistently higher asset turnover ratios than the other two companies, however, because higher depreciation expense in the earlier periods decreased its average total assets. In addition, the higher depreciation in earlier periods resulted in SOONER having lower operating profit margin and operating ROA in the first year and higher operating profit margin and operating ROA in the later periods. SOONER appears to be more efficiently run, on the basis of its higher asset turnover and greater increases in profit margin and ROA over time; however, these comparisons reflect differences in the companies’ choice of depreciation method. In addition, an analyst might question the sustainability of the extremely high ROAs for all three companies because such high profitability levels would probably attract new competitors, which would likely put downward pressure on the ratios.

EVEN-LI Co.

Year 1:

Total asset turnover ratio = 300,000/[(30,300+30,000+1,750)/2] = 300,000/31,025 = 9.67

Operating profit margin = (36,000 − 1,000 − 550)/300,000 = 34,450/300,000 = 11.48%

Operating ROA = 34,450/31,025 = 111.04%

Year 2:

Total asset turnover ratio = 320,000/[(30,000+1,750+32,000+1,200)/2] = 320,000/32,475 = 9.85

Operating profit margin = (38,400 − 1,000 − 550)/320,000 = 36,850/320,000 = 11.52%

Operating ROA = 36,850/32,475 = 113.47%

SOONER Inc.

Year 1:

Total asset turnover ratio = 300,000/[(30,300+30,000+1,150)/2] = 300,000/30,725 = 9.76

Operating profit margin = (36,000 − 1,000 − 1,150)/300,000 = 33,850/300,000 = 11.28%

Operating ROA = 33,850/30,725 = 110.17%

Year 2:

Total asset turnover ratio = 320,000/[(30,000+1,150+32,000+575)/2] = 320,000/31,862.50 = 10.04

Operating profit margin = (38,400 − 1,000 − 575)/320,000 = 36,825/320,000 = 11.51%

Operating ROA = 36,825/31,862.50 = 115.57%

AZUSED Co.

Year 1:

Total asset turnover ratio = 300,000/[(30,300+30,000+1,750)/2] = 300,000/31,025 = 9.67

Operating profit margin = (36,000 − 1,000 − 550)/300,000 = 34,450/300,000 = 11.48%

Operating ROA = 34,450/31,025 = 111.04%

Year 2:

Total asset turnover ratio = 320,000/[(30,000+1,750+32,000+925)/2] = 320,000/32,337.50 = 9.90

Operating profit margin = (38,400 − 1,000 − 825)/320,000 = 36,575/320,000 = 11.43%

Operating ROA = 36,575/32,337.50 = 113.10%

In many countries, a company must use the same depreciation methods for both financial and tax reporting. In other countries, including the United States, a company need not use the same depreciation method for financial reporting and taxes. As a result of using different depreciation methods for financial and tax reporting, pretax income on the income statement and taxable income on the tax return may differ. Thus, the amount of tax expense computed on the basis of pretax income and the amount of taxes actually owed on the basis of taxable income may differ. Although these differences eventually reverse because the total depreciation is the same regardless of the timing of its recognition in financial statements versus on tax returns, during the period of the difference, the balance sheet will show what is known as deferred taxes. For instance, if a company uses straight-line depreciation for financial reporting and an accelerated depreciation method for tax purposes, the company’s financial statements will report lower depreciation expense and higher pretax income in the first year, compared with the amount of depreciation expense and taxable income in its tax reporting. (Compare the depreciation expense in Year 1 for EVEN-LI Co. and SOONER Inc. in the previous example.) Tax expense calculated on the basis of the financial statements’ pretax income will be higher than taxes payable on the basis of taxable income; the difference between the two amounts represents a deferred tax liability. The deferred tax liability will be reduced as the difference reverses (i.e., when depreciation for financial reporting is higher than the depreciation for tax purposes) and the income tax is paid.

Significant estimates required for calculating depreciation include the useful life of the asset (or its total lifetime productive capacity) and its expected residual value at the end of that useful life. A longer useful life and higher expected residual value decrease the amount of annual depreciation expense relative to a shorter useful life and lower expected residual value. Companies should review their estimates periodically to ensure they remain reasonable. IFRS require companies to review estimates annually.

Although no significant differences exist between IFRS and U.S. GAAP with respect to the definition of depreciation and the acceptable depreciation methods, IFRS require companies to use a component method of depreciation.14 Companies are required to separately depreciate the significant components of an asset (parts of an item with a cost that is significant in relation to the total cost and/or with different useful lives) and thus require additional estimates for the various components. For instance, it may be appropriate to depreciate separately the engine, frame, and interior furnishings of an aircraft. Under U.S. GAAP, the component method of depreciation is allowed but is seldom used in practice.15 The following example illustrates depreciating components of an asset.

EXAMPLE 10-9 Illustration of Depreciating Components of an Asset

CUTITUP Co., a hypothetical company, purchases a milling machine, a type of machine used for shaping metal, at a total cost of $10,000. $2,000 was estimated to represent the cost of the rotating cutter, a significant component of the machine. The company expects the machine to have a useful life of eight years and a residual value of $3,000 and that the rotating cutter will need to be replaced every two years. Assume the entire residual value is attributable to the milling machine itself, and assume the company uses straight-line depreciation for all assets.

1. How much depreciation expense would the company report in Year 1 if it uses the component method of depreciation, and how much depreciation expense would the company report in Year 1 if it does not use the component method?

2. Assuming a new cutter with an estimated two-year useful life is purchased at the end of Year 2 for $2,000, what depreciation expenses would the company report in Year 3 if it uses the component method and if it does not use the component method?

3. Assuming replacement of the cutter every two years at a price of $2,000, what is the total depreciation expense over the eight years if the company uses the component method compared with the total depreciation expense if the company does not use the component method?

4. How many different items must the company estimate in the first year to compute depreciation expense for the milling machine if it uses the component method, and how does this compare with what would be required if it does not use the component method?

Solution to 1: Depreciation expense in Year 1 under the component method would be $1,625. For the portion of the machine excluding the cutter, the depreciable base is total cost minus the cost attributable to the cutter minus the estimated residual value = $10,000 − $2,000 − $3,000 = $5,000. Depreciation expense for the machine excluding the cutter in the first year equals $625 (depreciable cost divided by the useful life of the machine = $5,000/8 years). For the cutter, the depreciation expense equals $1,000 (depreciable cost divided by the useful life of the cutter = $2,000/2 years). Thus, the total depreciation expense for Year 1 under the component method is $1,625 (the sum of the depreciation expenses of the two components = $625+$1,000). Depreciation expense in Year 2 would also be $1,625.

If the company does not use the component method, depreciation expense in Year 1 is $875 (the depreciable cost of the total milling machine divided by its useful life = [$10,000 − $3,000]/8 years). Depreciation expense in Year 2 would also be $875.

Solution to 2: Assuming that at the end of Year 2, the company purchases a new cutter for $2,000 with an estimated two-year life, under the component method, the depreciation expense in Year 3 will remain at $1,625. If the company does not use the component method and purchases a new cutter with an estimated two-year life for $2,000 at the end of Year 2, the depreciation expense in Year 3 will be $1,875 [$875+($2,000/2) = $875+$1,000].

Solution to 3: Over the eight years, assuming replacement of the cutters every two years at a price of $2,000, the total depreciation expense will be $13,000 [$1,625 × 8 years] when the component method is used. When the component method is not used, the total depreciation expense will also be $13,000 [$875 × 2 years+$1,875 × 6 years]. This amount equals the total expenditures of $16,000 [$10,000+3 cutters × $2,000] less the residual value of $3,000.

Solution to 4: The following table summarizes the estimates required in the first year to compute depreciation expense if the company does or does not use the component method:

| Estimate | Required Using Component Method? | Required If Not Using Component Method? |

| Useful life of milling machine | Yes | Yes |

| Residual value of milling machine | Yes | Yes |

| Portion of machine cost attributable to cutter | Yes | No |

| Portion of residual value attributable to cutter | Yes | No |

| Useful life of cutter | Yes | No |

Total depreciation expense may be allocated between the cost of sales and other expenses. Within the income statement, depreciation expense of assets used in production is usually allocated to the cost of sales, and the depreciation expense of assets not used in production may be allocated to some other expense category. For instance, depreciation expense may be allocated to selling, general, and administrative expenses if depreciable assets are used in those functional areas. Notes to the financial statements sometimes disclose information regarding which income statement line items include depreciation expense, although the exact amount of detail disclosed by individual companies varies.

3.2. Amortization Methods and Calculation of Amortization Expense

Amortization is similar in concept to depreciation. The term amortization applies to intangible assets, and the term depreciation applies to tangible assets. Both terms refer to the process of allocating the cost of an asset over the asset’s useful life. Only those intangible assets assumed to have finite useful lives are amortized over their useful lives, following the pattern in which the benefits are used up. Acceptable amortization methods are the same as the methods acceptable for depreciation. Assets assumed to have an indefinite useful life (in other words, without a finite useful life) are not amortized. An intangible asset is considered to have an indefinite useful life when there is “no foreseeable limit to the period over which the asset is expected to generate net cash inflows” for the company.16

Intangible assets with finite useful lives include an acquired customer list expected to provide benefits to a direct-mail marketing company for two to three years, an acquired patent or copyright with a specific expiration date, an acquired license with a specific expiration date and no right to renew the license, and an acquired trademark for a product that a company plans to phase out over a specific number of years. Examples of intangible assets with indefinite useful lives include an acquired license that, although it has a specific expiration date, can be renewed at little or no cost and an acquired trademark that, although it has a specific expiration, can be renewed at a minimal cost and relates to a product that a company plans to continue selling for the foreseeable future.

As with depreciation for a tangible asset, the calculation of amortization for an intangible asset requires the original amount at which the intangible asset is recognized and estimates of the length of its useful life and its residual value at the end of its useful life. Useful lives are estimated on the basis of the expected use of the asset, considering any factors that may limit the life of the asset, such as legal, regulatory, contractual, competitive, or economic factors.

EXAMPLE 10-10 Amortization Expense

IAS 38 Intangible Assets provides illustrative examples regarding the accounting for intangible assets, including the following:

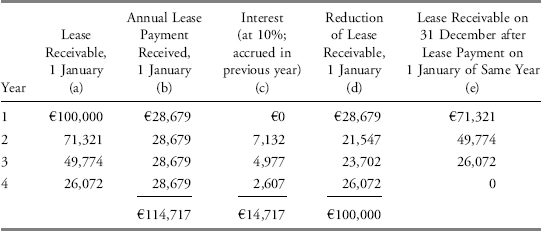

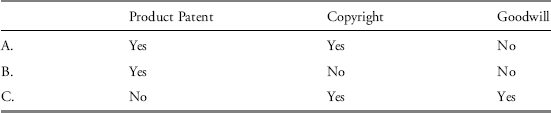

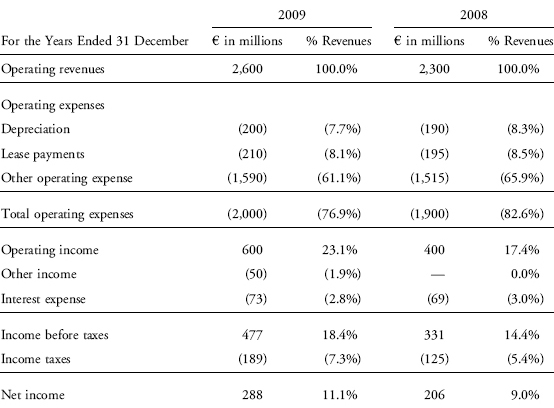

A direct-mail marketing company acquires a customer list and expects that it will be able to derive benefit from the information on the list for at least one year, but no more than three years. The customer list would be amortized over management’s best estimate of its useful life, say 18 months. Although the direct-mail marketing company may intend to add customer names and other information to the list in the future, the expected benefits of the acquired customer list relate only to the customers on that list at the date it was acquired.