CHAPTER 15

MULTINATIONAL OPERATIONS

After completing this chapter, you will be able to do the following:

- Distinguish among presentation currency, functional currency, and local currency.

- Analyze the impact of changes in exchange rates on the translated sales of the subsidiary and parent company.

- Compare and contrast the current rate method and the temporal method, evaluate the effects of each on the parent company’s balance sheet and income statement, and determine which method is appropriate in various scenarios.

- Calculate the translation effects, evaluate the translation of a subsidiary’s balance sheet and income statement into the parent company’s currency, and analyze the different effects of the current rate method and the temporal method on the subsidiary’s financial ratios.

- Analyze the effect on a parent company’s financial ratios of the currency translation method used.

- Analyze the effect of alternative translation methods for subsidiaries operating in hyperinflationary economies.

According to the World Trade Organization, merchandise exports worldwide exceeded US$10 trillion in 2005.1 The top five exporting countries, in order, were Germany, the United States, China, Japan, and France. From 2000 to 2005, international trade grew by 62 percent.

The U.S. Department of Commerce identified 239,100 U.S. companies as exporters in 2005. Only 3 percent of those companies were large (more than 500 employees). The vast majority of U.S. companies with export activity were small- or medium-sized entities.

The point made by these statistics is that many companies engage in transactions that cross national borders. The parties to these transactions must agree on the currency in which to settle the transaction. Generally this will be the currency of either the buyer or the seller. Exporters that receive payment in foreign currency and allow the purchaser time to pay must carry a foreign currency receivable on their books. Conversely, importers that agree to pay in foreign currency will have a foreign currency account payable. To be able to include them in the total amount of accounts receivable (payable) reported on the balance sheet, these foreign currency-denominated accounts receivable (payable) must be translated into the currency in which the exporter (importer) keeps its books and presents financial statements.

The prices at which foreign currencies can be purchased or sold are called foreign exchange rates. Because foreign exchange rates fluctuate over time, the value of foreign currency payables and receivables also fluctuates. The major accounting issue related to foreign currency transactions is how to reflect the changes in value for foreign currency payables and receivables in the financial statements.

Many companies have operations located in foreign countries. As examples, the Swiss food products company Nestlé SA reports that it has subsidiaries in more than 90 different countries, and U.S.-based Coca-Cola Company discloses that it has 144 foreign wholly owned subsidiaries located in 40 countries around the world. Foreign subsidiaries are generally required to keep accounting records in the currency of the country in which they are located. To prepare consolidated financial statements, the parent company must translate the foreign currency financial statements of its foreign subsidiaries into its own currency. Nestlé, for example, must translate the assets and liabilities its various foreign subsidiaries carry in foreign currency into Swiss francs to be able to consolidate those amounts with the Swiss franc assets and liabilities located in Switzerland.

A multinational company like Nestlé is likely to have two types of foreign currency activities that require special accounting treatment. Most multinationals (1) engage in transactions that are denominated in a foreign currency, and (2) invest in foreign subsidiaries that keep their books in a foreign currency. To prepare consolidated financial statements, a multinational company must translate the foreign currency amounts related to both types of international activities into the currency in which the company presents its financial statements.

This reading presents the accounting for foreign currency transactions and the translation of foreign currency financial statements. The conceptual issues related to these accounting topics are discussed and the specific rules embodied in International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) and U.S. GAAP are demonstrated through examples. Fortunately, differences between IFRS and U.S. GAAP with respect to foreign currency translation issues are minimal.

Analysts need to understand the impact that fluctuations in foreign exchange rates have on the financial statements of a multinational company and how foreign currency gains and losses, whether realized or not, are reflected in the company’s financial statements.

2. FOREIGN CURRENCY TRANSACTIONS

When companies from different countries agree to conduct business with one another, they must decide which currency will be used. For example, if a Mexican electronic components manufacturer agrees to sell goods to a customer in Finland, the two parties must agree whether the Finnish company will pay for the goods in Mexican pesos, euros, or perhaps even a third currency such as the U.S. dollar. If the transaction is denominated in Mexican pesos, the Finnish company has a foreign currency transaction but the Mexican company does not. To account for the inventory being purchased and the account payable in Mexican pesos, the Finnish company must translate the Mexican peso amounts into euros using appropriate exchange rates. Although the Mexican company also has entered into an international transaction (an export sale), it does not have a foreign currency transaction and no translation is necessary. It simply records the sales revenue and account receivable in Mexican pesos, which is the currency in which it keeps its books and prepares financial statements.

The currency in which financial statement amounts are presented is known as the presentation currency. In most cases, the presentation currency of a company will be the currency of the country where the company is located. Finnish companies are required to keep accounting records and present financial results in euros, U.S. companies in U.S. dollars, Chinese companies in Chinese yuan, and so on.

Another important concept in accounting for foreign currency activities is the functional currency, which is the currency of the primary economic environment in which an entity operates. Normally, the functional currency is the currency in which an entity primarily generates and expends cash. In most cases, the functional currency of an entity will be the same as its presentation currency. And, because most companies primarily generate and expend cash in the currency of the country where they are located, the functional and presentation currencies are most often the same as the local currency where the company operates.

Because the local currency generally is an entity’s functional currency, a multinational corporation with subsidiaries in a variety of different countries is likely to have a variety of different functional currencies. The Thai subsidiary of a Japanese parent company, for example, is likely to have the Thai baht as its functional currency whereas the Japanese parent’s functional currency is the Japanese yen. But in some cases, the foreign subsidiary could have the parent’s functional currency as its own. Intel Corporation, for example, has determined that all of its significant foreign subsidiaries have the U.S. dollar as their functional currency.

By definition, a foreign currency is any currency other than the functional currency of a company and foreign currency transactions are transactions that are denominated in a currency other than the company’s functional currency. Foreign currency transactions occur when a company (1) makes an import purchase or an export sale that is denominated in a foreign currency, or (2) borrows or lends funds where the amount to be repaid or received is denominated in a foreign currency. In each of these cases, the company has an asset or a liability that is denominated in a foreign currency.

2.1. Foreign Currency Transaction Exposure to Foreign Exchange Risk

Assume that FinnCo, a Finnish-based company, imports goods from Mexico in January under 90-day credit terms and the purchase is denominated in Mexican pesos. By deferring payment until April, FinnCo runs the risk that from the date the purchase is made until the date of payment, the value of the Mexican peso might increase relative to the euro. FinnCo would then need to spend more euros to settle its Mexican peso account payable. In this case, FinnCo is said to have an exposure to foreign exchange risk. Specifically, FinnCo has a foreign currency transaction exposure. Transaction exposure related to imports and exports can be summarized as follows:

Import purchase: A transaction exposure arises when the importer is obligated to pay in foreign currency and is allowed to defer payment until sometime after the purchase date. The importer is exposed to the risk that from the purchase date until the payment date the foreign currency might increase in value, thereby increasing the amount of functional currency that must be spent to acquire enough foreign currency to settle the account payable.

Export sale: A transaction exposure arises when the exporter agrees to be paid in foreign currency and allows payment to be made sometime after the purchase date. The exporter is exposed to the risk that from the purchase date until the payment date the foreign currency might decrease in value, thereby decreasing the amount of functional currency into which the foreign currency can be converted when it is received.

The major issue in accounting for foreign currency transactions is how to account for the foreign currency risk; that is, how to reflect in the financial statements the change in value of the foreign currency asset or liability. Both International Accounting Standard (IAS) 21, “The Effects of Changes in Foreign Exchange Rates,” and FASB Statement (SFAS) 52, “Foreign Currency Translation,” require the change in the value of the foreign currency asset or liability resulting from a foreign currency transaction to be treated as a gain or loss reported on the income statement.2

2.1.1. Accounting for Foreign Currency Transactions with Settlement before Balance Sheet Date

Example 15-1 demonstrates the accounting that would be done by FinnCo assuming that it purchased goods on account from a Mexican supplier who required payment in Mexican pesos, and that it made payment before the balance sheet date. The basic principle is that all transactions are recorded at the spot rate on the date of the transaction. The foreign currency risk on transactions, therefore, only arises when the transaction date and the payment date are different.

EXAMPLE 15-1 Accounting for Foreign Currency Transactions with Settlement before the Balance Sheet Date

FinnCo purchases goods from its Mexican supplier on 1 November 2008; the purchase price is 100,000 Mexican pesos. Credit terms allow payment in 45 days, and FinnCo makes payment of 100,000 pesos on 15 December 2008. FinnCo’s functional and presentation currency is the euro. Spot exchange rates between the euro (€) and Mexican peso (Ps.) are as follows:

1 November 2008 Ps. 1 = €0.0684

15 December 2008 Ps. 1 = €0.0703

FinnCo’s fiscal year-end is 31 December. How will FinnCo account for this foreign currency transaction and what effect will it have on the 2008 financial statements?

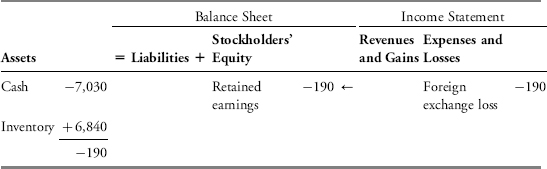

Solution: The euro value of the Mexican peso account payable on 1 November 2008 was €6,840 (Ps. 100,000 × €0.0684). FinnCo could have paid for its inventory on 1 November by converting 6,840 euros into 100,000 Mexican pesos. Instead, the company purchases 100,000 Mexican pesos on 15 December 2008, when the value of the peso has increased to €0.0703. Thus, FinnCo pays 7,030 euros to purchase 100,000 Mexican pesos. This results in a loss of 190 euros (€7,030 − €6,840).

Although the cash outflow to acquire the inventory is €7,030, the cost included in the inventory account is only €6,840. This represents the amount that FinnCo could have paid if it had not waited 45 days to settle its account. By deferring payment, and because the Mexican peso increased in value between the transaction date and settlement date, FinnCo has to pay an additional 190 euros. A foreign exchange loss of €190 will be reported in FinnCo’s net income in 2008. This is a realized loss in that the company actually spent an additional 190 euros to purchase its inventory. The net effect on the financial statements can be seen as follows:

2.1.2. Accounting for Foreign Currency Transactions with Intervening Balance Sheet Dates

Another important issue related to the accounting for foreign currency transactions is what should be done, if anything, if a balance sheet date falls between the initial transaction date and the settlement date. For foreign currency transactions that occur with settlement dates that fall in subsequent accounting periods, both IFRS and U.S. GAAP require adjustments to reflect intervening changes in currency exchange rates. Foreign currency transaction gains and losses are reported on the income statement, creating one of the very few situations in which accounting rules allow, indeed require, companies to include (recognize) an unrealized gain or loss in income before it has been realized.

Subsequent foreign currency transaction gains and losses are recognized from the balance sheet date through the date the transaction is settled. Adding together foreign currency transaction gains and losses for both accounting periods (transaction initiation to balance sheet date and balance sheet date to transaction settlement) produces an amount equal to the actual realized gain or loss on the foreign currency transaction.

EXAMPLE 15-2 Accounting for Foreign Currency Transaction with Intervening Balance Sheet Date

FinnCo sells goods to a customer in the United Kingdom for £10,000 on 15 November 2008, with payment to be received in British pounds on 15 January 2009. FinnCo’s functional and presentation currency is the euro. Spot exchange rates between the euro (€) and British pound (£) are as follows:

15 November 2008 £1 = €1.460

31 December 2008 £1 = €1.480

15 January 2009 £1 = €1.475

FinnCo’s fiscal year-end is 31 December. How will FinnCo account for this foreign currency transaction and what effect will it have on the 2008 and 2009 financial statements?

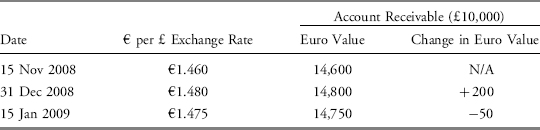

Solution: The euro value of the British pound account receivable at each of the three relevant dates is determined as follows:

A change in the euro value of the British pound receivable from 15 November to 31 December would be recognized as a foreign currency transaction gain or loss on FinnCo’s 2008 income statement. In this case, the increase in the value of the British pound results in a transaction gain of €200 [£10,000 × (€1.48 − €1.46)]. Note that the gain recognized in 2008 income is unrealized and remember that this is one of few situations where companies include an unrealized gain in income.

Any change in the exchange rate between the euro and British pound that occurs from the balance sheet date (31 December 2008) to the transaction settlement date (15 January 2009) likewise will result in a foreign currency transaction gain or loss. In our example, the British pound weakened slightly against the euro during this period, resulting in an exchange rate of €1.475 per British pound on 15 January 2009. The £10,000 account receivable now has a value of €14,750, which is a decrease in value of €50 from 31 December 2008. FinnCo will recognize a foreign currency transaction loss on 15 January 2009 of €50 that will be included in the company’s calculation of net income for the first quarter of 2009.

From the transaction date to the settlement date, the British pound has increased in value by €0.015 (€1.475 − €1.46), which generates a realized foreign currency transaction gain of €150. A gain of €200 was recognized in 2008 and a loss of €50 is recognized in 2009. Over the two-month period, the net gain recognized in the financial statements is equal to the actual realized gain on the foreign currency transaction.

In Example 15-2, FinnCo’s British pound account receivable resulted in a net foreign currency transaction gain because the British pound strengthened (increased) in value between the transaction date and the settlement date. In this case FinnCo has an asset exposure to foreign exchange risk. This asset exposure benefited the company because the foreign currency strengthened. If FinnCo instead had a British pound account payable, a liability exposure would have existed. The euro value of the British pound account payable would have increased as the British pound strengthened and FinnCo would have recognized a foreign currency transaction loss as a result.

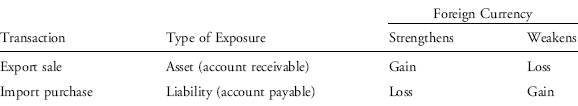

Whether a change in exchange rate results in a foreign currency transaction gain or loss depends on (1) the nature of the exposure to foreign exchange risk (asset or liability) and (2) the direction of change in the value of the foreign currency (strengthens or weakens).

A foreign currency receivable arising from an export sale creates an asset exposure to foreign exchange risk. If the foreign currency strengthens, the receivable increases in value in terms of the company’s functional currency and a foreign currency transaction gain arises. The company will be able to convert the foreign currency when received into more units of functional currency because the foreign currency has strengthened. Conversely, if the foreign currency weakens, the foreign currency receivable loses value in terms of the functional currency and a loss results.

A foreign currency payable resulting from an import purchase creates a liability exposure to foreign exchange risk. If the foreign currency strengthens, the payable increases in value in terms of the company’s functional currency and a foreign currency transaction loss arises. The company will have to spend more units of functional currency to be able to settle the foreign currency liability because the foreign currency has strengthened. Conversely, if the foreign currency weakens, the foreign currency payable loses value in terms of the functional currency and a gain exists.

2.2. Analytical Issues

Both IFRS (IAS 21) and U.S. GAAP (FASB 52) require foreign currency transaction gains and losses to be reported in net income (even if they have not yet been realized), but neither standard indicates where on the income statement these gains and losses should be placed. The two most common treatments are (1) as a component of other operating income/expense or (2) as a component of nonoperating income/expense, in some cases as a part of net financing cost. The calculation of operating profit margin is affected by where foreign currency transaction gains or losses are placed on the income statement.

Because accounting standards do not provide guidance on the placement of foreign currency transaction gains and losses on the income statement, companies are free to choose among the alternatives. Two companies in the same industry could choose different alternatives, which would distort the direct comparison of operating profit and operating profit margins between those companies.

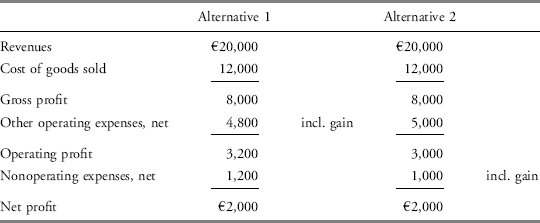

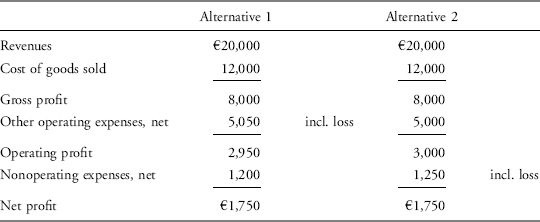

EXAMPLE 15-3 Placement of Foreign Currency Transaction Gains/Losses on the Income Statement—Effect on Operating Profit

Assume that FinnCo had the following income statement information in both 2008 and 2009, excluding a foreign currency transaction gain of €200 in 2008 and a transaction loss of €50 in 2009.

| 2008 | 2009 | |

| Revenues | €20,000 | €20,000 |

| Cost of goods sold | 12,000 | 12,000 |

| Other operating expenses, net | 5,000 | 5,000 |

| Nonoperating expenses, net | 1,200 | 1,200 |

FinnCo is deciding between two alternatives for the treatment of foreign currency transaction gains and losses. Alternative 1 calls for the reporting of foreign currency transaction gains/losses as part of “other operating expenses, net.” Under Alternative 2, the company would report this information as part of “nonoperating expenses, net.”

FinnCo’s fiscal year-end is 31 December. What impact will the decision of Alternatives 1 and 2 have on the company’s gross profit margin, operating profit margin, and net profit margin for 2008? For 2009?

Solution: Remember that a gain would serve to reduce expenses whereas a loss would have the effect of increasing expenses.

2008—Transaction Gain of €200

Profit margins in 2008 under the two alternatives would be calculated as follows:

| Alternative 1 | Alternative 2 | |

| Gross profit margin | €8,000/€20,000 = 40.0% | €8,000/€20,000 = 40.0% |

| Operating profit margin | 3,200/20,000 = 16.0% | 3,000/20,000 = 15.0% |

| Net profit margin | 2,000/20,000 = 10.0% | 2,000/20,000 = 10.0% |

2009—Transaction Loss of €50

Profit margins in 2009 under the two alternatives would be calculated as follows:

| Alternative 1 | Alternative 2 | |

| Gross profit margin | €8,000/€20,000 = 40.0% | €8,000/€20,000 = 40.0% |

| Operating profit margin | 2,950/20,000 = 14.75% | 3,000/20,000 = 15.0% |

| Net profit margin | 1,750/20,000 = 8.75% | 1,750/20,000 = 8.75% |

Gross profit and net profit are unaffected, but operating profit differs under the two alternatives. In 2008, the operating profit margin is larger under Alternative 1, which includes the transaction gain as part of “other operating expenses, net.” In 2009, Alternative 1 results in a smaller operating profit margin than Alternative 2. Alternative 2 has the same operating profit margin in both periods. Because exchange rates do not fluctuate by the same amount or in the same direction from one accounting period to the next, Alternative 1 will cause greater volatility in operating profit and operating profit margin over time.

A second issue that should be of interest to analysts relates to the fact that unrealized foreign currency transaction gains and losses are included in net income when the balance sheet date falls between the transaction and settlement dates. The implicit assumption underlying this accounting requirement is that the unrealized gain or loss as of the balance sheet date is reflective of the ultimate net gain or loss to the company. In reality, though, the ultimate net gain or loss may vary dramatically because of the possibility for changes in trend and volatility of currency prices.

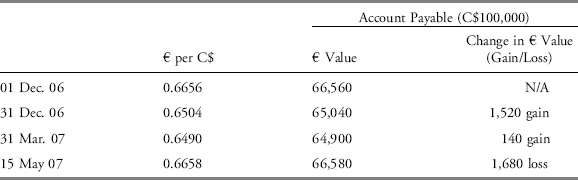

This effect was seen in the previous hypothetical Example 15-2 with FinnCo. Using actual currency exchange rate data shows that the real-world effect can also be quite dramatic. Assume that a French company purchased goods from a Canadian supplier on 1 December 2006, with payment of 100,000 Canadian dollars (C$) to be made on 15 May 2007. Actual exchange rates between the Canadian dollar and euro during the period 1 December 2006 and 15 May 2007, the euro value of the Canadian dollar account payable, and foreign currency transaction gain or loss are shown here:

As the Canadian dollar weakened against the euro in late 2006 and early 2007, the French company would have recorded a foreign currency transaction gain of €1,520 in the fourth quarter of 2006 and an additional transaction gain of €140 in the first quarter of 2007. The Canadian dollar reversed course and strengthened against the euro in the second quarter of 2007, resulting in a transaction loss of €1,680. At the time payment is made on 15 May 2007, the French company realizes a net foreign currency transaction loss of €20 (€66,580 − €66,560). In this case, the transaction gains reported in net income in 2006 and the first quarter of 2007 did not accurately reflect the loss that ultimately was realized.

2.3. Disclosures Related to Foreign Currency Transaction Gains and Losses

Because accounting rules allow companies to choose where they present foreign currency transaction gains and losses on the income statement it is useful for companies to disclose both the amount of transaction gain or loss that is included in income and the presentation alternative they have selected. IAS 21 requires disclosure of “the amount of exchange differences recognized in profit or loss” and SFAS 52 requires disclosure of “the aggregate transaction gain or loss included in determining net income for the period,” but neither standard specifically requires disclosure of the line item in which these gains and losses are located.

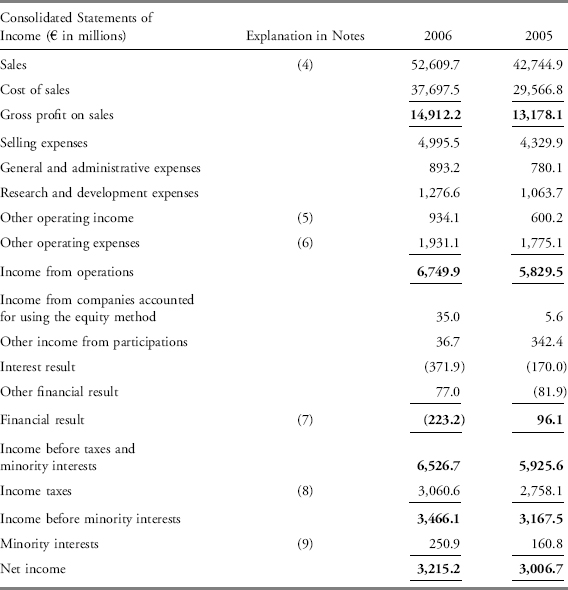

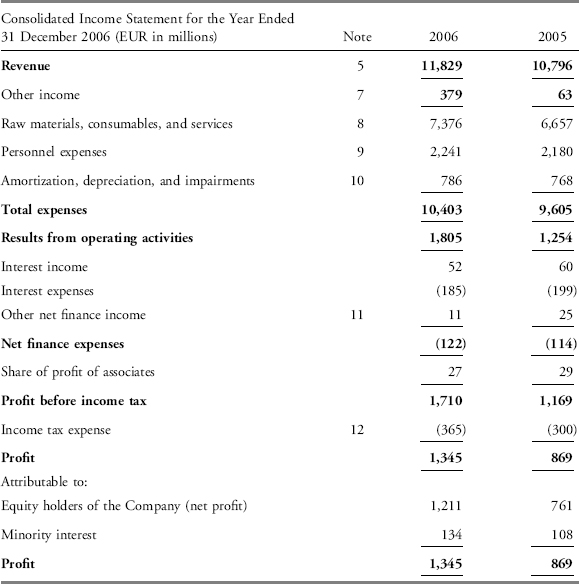

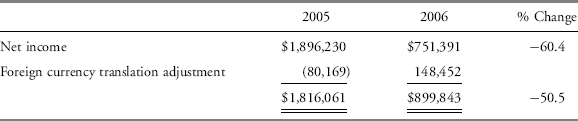

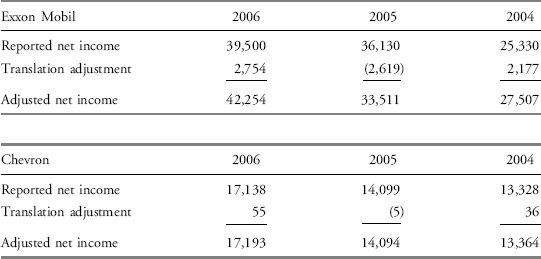

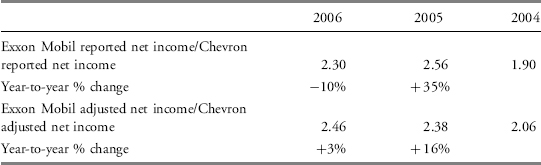

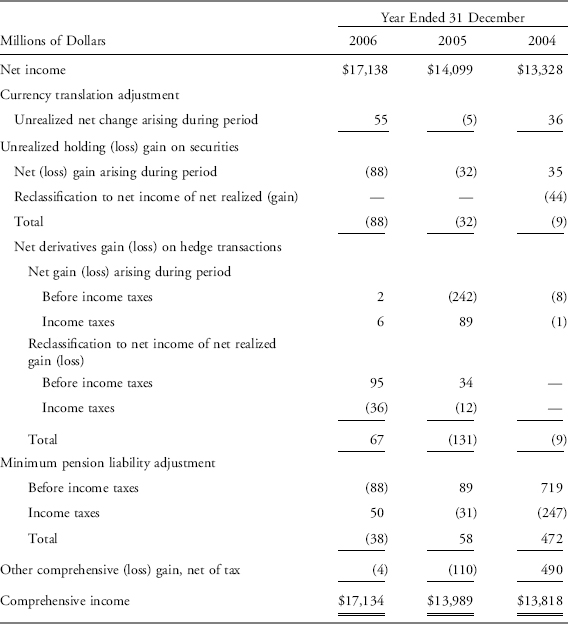

Exhibit 15-1 provides disclosures from BASF AG’s 2006 Annual Report that the German company made related to foreign currency transaction gains and losses. Exhibit 15-2 presents similar disclosures found in the Netherlands-based Heineken NV’s 2006 Annual Report. Both companies use IFRS to prepare their consolidated financial statements.

BASF’s income statement in Exhibit 15-1 does not include a separate line item for foreign currency gains and losses. From Note 5 in Exhibit 15-1, an analyst can determine that BASF has chosen to include “Gains from foreign currency transactions” in Other operating income. Of the total amount of €934.1 million reported as Other operating income in 2006, €119.7 million is attributable to foreign currency transaction gains. It is not possible to determine from BASF’s financial statements whether these gains were realized in 2006 or not. And any unrealized gain reported in 2006 income might or might not be realized in 2007.

Note 6 in Exhibit 15-1 indicates that “Losses from foreign currency transactions” in 2006 were €48.4 million, making up 2.5 percent of Other operating expenses. Combining foreign currency transaction gains and losses results in a net gain of €71.3 million, which comprised 1.06 percent of BASF’s Income from operations.

Exhibit 15-1 Excerpts from BASF AG’s 2006 Annual Report Related to Foreign Currency Transactions

Notes

1. Summary of Accounting Policies

Foreign currency transactions: The cost of assets acquired in foreign currencies and revenues from sales in foreign currencies are recorded at the exchange rate at the date of the transaction. Foreign currency receivables and liabilities are valued at the exchange rates on the balance sheet date.

5. Other Operating Income

| (€ in millions) | 2006 | 2005 |

| Reversal and adjustment of provisions | 275.2 | 118.4 |

| Revenue from miscellaneous revenue-generating activities | 62.3 | 85.3 |

| Gains from foreign currency transactions | 119.7 | 43.3 |

| Gains from the translation of financial statements in foreign currencies | 10.8 | 57.3 |

| Gains from disposal of property, plant and equipment and divestitures | 127.8 | 107.4 |

| Gains on the reversal of allowance for doubtful receivables | 89.0 | 92.1 |

| Other | 249.3 | 96.4 |

| 934.1 | 600.2 |

Gains from foreign currency transactions represent gains arising from foreign currency positions and foreign currency derivatives as well as from the valuation of receivables and liabilities denominated in foreign currencies at the spot rate at the balance sheet date.

6. Other Operating Expenses

| (€ in millions) | 2006 | 2005 |

| Integration and restructuring measures | 399.4 | 446.5 |

| Environmental protection and safety measures, costs of demolition and planning costs related to the preparation of capital expenditure projects not subject to mandatory capitalization | 180.5 | 158.3 |

| Amortization of intangible assets and depreciation of property, plant and equipment | 430.3 | 204.6 |

| Costs from miscellaneous revenue-generating activities | 85.1 | 84.7 |

| Losses from foreign currency transactions | 48.4 | 189.5 |

| Losses from the translation of financial statements in foreign currencies | 51.6 | 23 |

| Losses from the disposal of property, plant and equipment | 21.8 | 15.5 |

| Oil and gas exploration expenses | 167.3 | 172.9 |

| Expenses from additions to allowances for doubtful receivables | 90.4 | 102.9 |

| Other | 456.3 | 377.2 |

| 1,931.1 | 1,775.1 |

Losses from foreign currency transactions include losses from foreign currency positions and derivatives and the valuation of receivables and liabilities in foreign currencies at the closing rate on the balance sheet date.

In Exhibit 15-2, Heineken’s Note 2, Basis of Preparation, part (c) explicitly states that the euro is the company’s functional currency. Note 3(b)(i) indicates that monetary assets and liabilities denominated in foreign currencies at the balance sheet are translated to the functional currency and foreign currency differences arising on the translation (i.e., translation gains and losses) are recognized on the income statement. Note 3(o) discloses that foreign currency gains are included in Other finance income and foreign currency losses are included in Other finance expense. These two amounts are combined into a part of the line item reported on the income statement as Other net finance income. Note 11, Other net finance income, shows that a net translation loss of €16 million existed in 2006 and a net gain of €19 million arose in 2005. The net foreign currency transaction gain in 2005 amounted to 1.63 percent of Heineken’s profit before income tax that year, while the net translation loss in 2006 represented 0.94 percent of the company’s profit before income tax in that year.

Exhibit 15-2 Excerpts from Heineken NV’s 2006 Annual Report Related to Foreign Currency Transactions

Notes

2. Basis of preparation

(c) Functional and presentation currency

These consolidated financial statements are presented in euros, which is the company’s functional currency. All financial information presented in euros has been rounded to the nearest million.

3. Significant accounting policies

(b) Foreign currency

(i) Foreign currency transactions

Transactions in foreign currencies are translated to the respective functional currencies of Heineken entities at the exchange rates at the dates of the transactions. Monetary assets and liabilities denominated in foreign currencies at the balance sheet date are retranslated to the functional currency at the exchange rate at that date.. . .Foreign currency differences arising on retranslation are recognized in the income statement, except for differences arising on the retranslation of available-for-sale (equity) investments.3

(o) Interest income, interest expenses and other net finance expenses

Other finance income comprises dividend income, gains on the disposal of available-for-sale financial assets, changes in the fair value of financial assets at fair value through profit or loss, foreign currency gains, and gains on hedging instruments that are recognized in the income statement. Dividend income is recognized on the date that Heineken’s right to receive payment is established, which in the case of quoted securities is the ex-dividend date.

Other finance expenses comprise unwinding of the discount on provisions, changes in the fair value of financial assets at fair value through profit or loss, foreign currency losses, impairment losses recognized on financial assets, and losses on hedging instruments that are recognized in the income statement.

11. Other Net Finance Income

| (€ in millions) | 2006 | 2005 |

| Impairment investments | — | (6) |

| Dividend income | 13 | 13 |

| Exchange rate differences | (16) | 19 |

| Other | 14 | (1) |

| 11 | 25 |

In applying U.S. GAAP’s SFAS 52 to account for its foreign currency transactions, Yahoo! Inc. reported the following in its Quantitative and Qualitative Disclosures about Market Risk in its 2006 Annual Report:

In the year ended December 31, 2006, we recorded net foreign currency transaction gains, realized and unrealized, of approximately $5 million, net losses of $8 million and net gains of $6 million in 2005 and 2004, respectively, which were recorded in other income, net on the consolidated statements of income.

Yahoo! explicitly acknowledges that both realized and unrealized foreign currency transaction gains and losses are reflected in income, specifically as a part of nonoperating activities. The net foreign currency transaction gain in 2006 of $5 million represented only 0.6 percent of the company’s net income for the year.

Companies often neglect to disclose either the location or the amount of foreign currency transaction gains and losses, presumably because the amounts involved are immaterial. The disclosure made by Altria Group, Inc. in its 2006 Annual Report is indicative of this approach. Note 2, Summary of Significant Accounting Policies, contains a subheading “Foreign Currency Translation,” in which the company states:

Transaction gains and losses are recorded in the consolidated statements of earnings and were not significant for any of the periods presented.

There are several reasons why the amount of transaction gains and losses can be immaterial for a company:

1. The company engages in a limited number of foreign currency transactions that involve relatively small amounts of foreign currency.

2. The exchange rates between the company’s functional currency and the foreign currencies in which it has transactions tend to be relatively stable.

3. Gains on some foreign currency transactions are naturally offset by losses on other transactions, such that the net gain or loss is immaterial. For example, if a U.S. company sells goods to a customer in Canada with payment in Canadian dollars to be received in 90 days and at the same time purchases goods from a supplier in Canada with payment to be made in Canadian dollars in 90 days, any loss that arises on the Canadian dollar receivable due to a weakening in the value of the Canadian dollar will be exactly offset by a gain of equal amount on the Canadian dollar payable.

4. The company engages in foreign currency hedging activities to offset the foreign exchange gains and losses that arise from foreign currency transactions. Hedging foreign exchange risk is a common practice for many companies engaged in foreign currency transactions.

The two most common types of hedging instruments used to minimize foreign exchange risk are foreign currency forward contracts and foreign currency options. Corning, Inc. describes its foreign exchange risk management approach in its 2006 Annual Report in Note 15, Hedging Activities. An excerpt from that note follows:

We operate and conduct business in many foreign countries and as a result are exposed to movements in foreign currency exchange rates. Our exposure to exchange rate effects includes:

- Exchange rate movements on financial instruments and transactions denominated in foreign currencies that impact earnings, and

- Exchange rate movements upon translation of net assets in foreign subsidiaries for which the functional currency is not the U.S. dollar that impact our net equity.4

Our most significant foreign currency exposures related to Japan, Korea, Taiwan, and western European countries. We selectively enter into foreign exchange forward and option contracts with durations generally 15 months or less to hedge our exposure to exchange rate risk on foreign source income and purchases. The hedges are scheduled to mature coincident with the timing of the underlying foreign currency commitments and transactions. The objective of these contracts is to neutralize the impact of exchange rate movements on our operating results.

We engage in foreign currency hedging activities to reduce the risk that changes in exchange rates will adversely affect the eventual net cash flows resulting from the sale of products to foreign customers and purchases from foreign suppliers. The hedge contracts reduce the exposure to fluctuations in exchange rate movements because the gains and losses associated with foreign currency balances and transactions are generally offset with gains and losses of the hedge contracts. Because the impact of movements in foreign exchange rates on the value of hedge contracts offsets the related impact on the underlying items being hedged, these financial instruments help alleviate the risk that might otherwise result from currency exchange rate fluctuations.

Corning goes on to indicate that “changes in the fair value of undesignated hedges are recorded in current period earnings in the other income, net component, along with the foreign currency gains and losses arising from the underlying monetary assets or liabilities in the consolidated statement of operations” (p. 171, emphasis added). Amounts, however, are not disclosed, presumably because they are immaterial.

3. TRANSLATION OF FOREIGN CURRENCY FINANCIAL STATEMENTS

Many companies have operations in foreign countries. Most operations located in foreign countries keep their accounting records and prepare financial statements in the local currency. For example, the U.S. subsidiary of German automaker BMW AG keeps its books in U.S. dollars. IFRS and U.S. GAAP require parent companies to prepare consolidated financial statements in which the assets, liabilities, revenues, and expenses of both domestic and foreign subsidiaries are added to those of the parent company. To prepare worldwide consolidated statements, parent companies must translate the foreign currency financial statements of their foreign subsidiaries into the parent company’s presentation currency. BMW AG, for example, must translate the U.S. dollar financial statements of its U.S. subsidiary and the South African rand financial statements of its South African subsidiary into euros to consolidate these foreign operations.

The IASB (in IAS 21) and FASB (in SFAS 52) have established very similar rules for the translation of foreign currency financial statements. To fully understand the results from applying these rules, however, several conceptual issues must first be examined.

3.1. Translation Conceptual Issues

In translating foreign currency financial statements into the parent company’s presentation currency, two questions must be addressed:

1. What is the appropriate exchange rate to be used in translating each financial statement item?

2. How should the translation adjustment that inherently arises from the translation process be reflected in the consolidated financial statements? In other words, how is the balance sheet brought back into balance?

These issues and the basic concepts underlying the translation of financial statements are demonstrated through the following example.

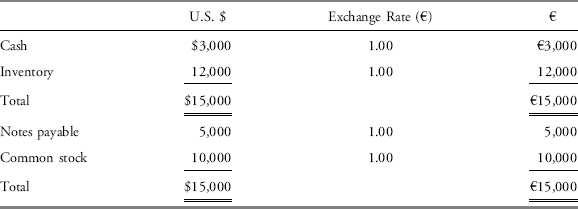

Spanco is a hypothetical Spanish-based company that uses the euro as its presentation currency. Spanco establishes a wholly owned subsidiary, Amerco, in the United States on 31 December 2008 by investing €10,000 when the exchange rate between the euro and the U.S. dollar is €1 = US$1. The equity investment of €10,000 is physically converted into US$10,000 to begin operations. In addition, Amerco borrows US$5,000 from local banks on 31 December 2008. Amerco purchases inventory that costs US$12,000 on 31 December 2008, and retains US$3,000 in cash. Amerco’s balance sheet at 31 December 2008 appears as follows:

Amerco Balance Sheet at 31 December 2008 (in U.S. Dollars)

To prepare a consolidated balance sheet in euros at 31 December 2008, Spanco must translate all of the U.S. dollar balances on Amerco’s balance sheet at the €1 = US$1 exchange rate. The translation worksheet at 31 December 2008 is as follows:

Translation Worksheet for Amerco, 31 December 2008

By translating each U.S. dollar balance at the same exchange rate (€1.00), Amerco’s translated balance sheet in euros reflects an equal amount of total assets and total liabilities plus equity and remains in balance.

During the first quarter of 2009, Amerco engages in no transactions. However, during that period the U.S. dollar weakens against the euro such that the exchange rate at 31 March 2009 is €0.80 = US$1.

To prepare a consolidated balance sheet at the end of the first quarter 2009, Spanco now must choose between the current exchange rate of €0.80 and the historical exchange rate of €1.00 to translate Amerco’s balance sheet amounts into euros. The original investment made by Spanco of €10,000 is a historical fact, so the company wants to translate Amerco’s common stock in such a way that it continues to reflect this amount. This is achieved by translating common stock of US$10,000 into euros using the historical exchange rate of €1 = US$1.

Two different approaches for translating the foreign subsidiary’s assets and liabilities are:

1. All assets and liabilities are translated at the current exchange rate (the spot exchange rate on the balance sheet date), or

2. Only monetary assets and liabilities are translated at the current exchange rate; nonmonetary assets and liabilities are translated at historical exchange rates (the exchange rates that existed when the assets and liabilities were acquired). Monetary items are cash and receivables (payables) that are to be received (paid) in a fixed number of currency units. Nonmonetary assets include inventory, fixed assets, and intangibles, and nonmonetary liabilities include deferred revenue.

These two different approaches are demonstrated and the results analyzed in turn.

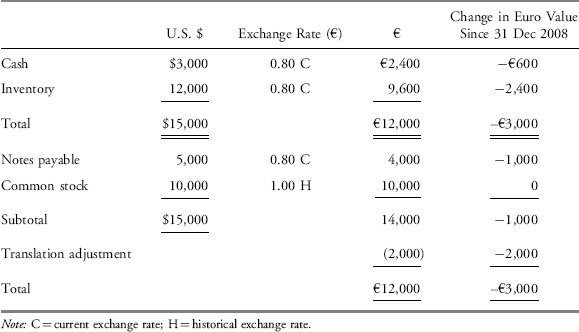

3.1.1. All Assets and Liabilities Are Translated at the Current Exchange Rate

The translation worksheet at 31 March 2009 in which all assets and liabilities are translated at the current exchange rate (€0.80) is as follows:

Translation Worksheet for Amerco, 31 March 2009

By translating all assets at the lower current exchange rate, total assets are written down from 31 December 2008 to 31 March 2009 in terms of their euro value by €3,000. Liabilities are written down by €1,000. To keep the euro translated balance sheet in balance, a negative translation adjustment of €2,000 is created and included in stockholders’ equity on the consolidated balance sheet.

Those foreign currency balance sheet accounts that are translated using the current exchange rate are revalued in terms of the parent’s functional currency. This process is very similar to the revaluation of foreign currency receivables and payables related to foreign currency transactions. The net translation adjustment that results from translating individual assets and liabilities at the current exchange rate can be viewed as the net foreign currency translation gain or loss caused by a change in the exchange rate:

| (€600) | loss on cash |

| (€2,400) | loss on inventory |

| €1,000 | gain on notes payable |

| (€2,000) | net translation loss |

The negative translation adjustment (net translation loss) does not result in a cash outflow of €2,000 for Spanco and thus is unrealized. The loss could be realized, however, if Spanco were to sell Amerco at its book value of US$10,000. The proceeds from the sale would be converted into euros at €0.80 per US$1, resulting in a cash inflow of €8,000. Because Spanco originally invested €10,000 in its U.S. operation, a realized loss of €2,000 would result.

The second conceptual issue related to the translation of foreign currency financial statements is whether the unrealized net translation loss should be included in the determination of consolidated net income currently or should be deferred in the stockholders’ equity section of the consolidated balance sheet until the loss is realized through sale of the foreign subsidiary. There is some debate as to which of these two treatments is most appropriate. This issue is discussed in more detail after considering the second approach for translating assets and liabilities.

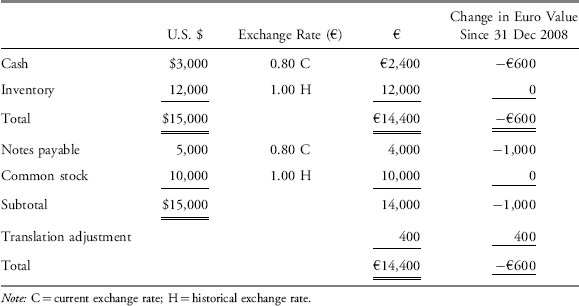

3.1.2. Only Monetary Assets and Monetary Liabilities Are Translated at the Current Exchange Rate

Now assume only monetary assets and monetary liabilities are translated at the current exchange rate. The translation worksheet at 31 March 2009 in which only monetary assets and liabilities are translated at the current exchange rate (€0.80) is as follows:

Translation Worksheet for Amerco, 31 March 2009

Using this approach, cash is written down by €600 but inventory continues to be carried at its euro historical cost of €12,000. Notes payable is written down by €1,000. To keep the balance sheet in balance, a positive translation adjustment of €400 must be included in stockholders’ equity. The translation adjustment reflects the net translation gain or loss related to monetary items only:

| (€600) | loss on cash |

| €1,000 | gain on notes payable |

| €400 | net translation gain |

The positive translation adjustment (net translation gain) also is unrealized. However, the gain could be realized if:

- The subsidiary uses its cash (US$3,000) to pay as much of its liabilities as possible.

- The parent sends enough euros to the subsidiary to pay its remaining liabilities (US$5,000 − US$3,000 = US$2,000). At 31 December 2008, at the €1.00 per US$1 exchange rate, Spanco would have sent €2,000 to Amerco to pay liabilities of US$2,000. At 31 March 2009, given the €0.80 per US$1 exchange rate, the parent needs to send only €1,600 to pay US$2,000 of liabilities. As a result, Spanco would enjoy a foreign exchange gain of €400.

The second conceptual issue again arises under this approach. Should the unrealized foreign exchange gain be recognized in current period net income or deferred on the balance sheet as a separate component of stockholders’ equity? The answer to this question, as provided by IFRS and U.S. GAAP, is described in Section 3.2, Translation Methods.

3.1.3. Balance Sheet Exposure

Those assets and liabilities translated at the current exchange rate are revalued from balance sheet to balance sheet in terms of the parent company’s presentation currency. These items are said to be exposed to translation adjustment. Balance sheet items translated at historical exchange rates do not change in parent currency value and therefore are not exposed to translation adjustment. Exposure to translation adjustment is referred to as balance sheet translation, or accounting exposure.

A foreign operation will have a net asset balance sheet exposure when assets translated at the current exchange rate are greater in amount than liabilities translated at the current exchange rate. A net liability balance sheet exposure exists when liabilities translated at the current exchange rate are greater than assets translated at the current exchange rate. Another way to think about the issue is to realize that there is a net asset balance sheet exposure when exposed assets are greater in amount than exposed liabilities and a net liability balance sheet exposure when exposed liabilities are greater in amount than exposed assets. The sign (positive or negative) of the current period’s translation adjustment is a function of two factors: (1) the nature of the balance sheet exposure (asset or liability) and (2) the direction of change in the exchange rate (strengthens or weakens). The relationship between exchange rate fluctuations, balance sheet exposure, and the current period’s translation adjustment can be summarized as follows:

| Foreign Currency (FC) | ||

| Balance Sheet Exposure | Strengthens | Weakens |

| Net asset | Positive translation adjustment | Negative translation adjustment |

| Net liability | Negative translation adjustment | Positive translation adjustment |

These relationships are the same as those summarized in Section 2.2 with respect to foreign currency transaction gains and losses. In reference to the example in Section 3.1.2, for instance, exposed assets ($3,000) were less than exposed liabilities ($5,000), implying that there was a net liability exposure. Further, the foreign currency (US$) weakened, resulting in a positive translation adjustment.

The combination of balance sheet exposure and direction of exchange rate change determines whether the current period’s translation adjustment will be positive or negative. After the initial period of operations, a cumulative translation adjustment is required to keep the translated balance sheet in balance. The cumulative translation adjustment will be the sum of the translation adjustments that arise over successive accounting periods. For example, assume that Spanco translates all of Amerco’s assets and liabilities using the current exchange rate (a net asset balance sheet exposure exists), which due to a weakening U.S. dollar in the first quarter of 2009 resulted in a negative translation adjustment at 31 March 2009 of €2,000 (as shown in Section 3.1.1). Assume further that in the second quarter of 2009, the U.S. dollar strengthens against the euro and there still is a net asset balance sheet exposure, which results in a positive translation adjustment of €500 for that quarter. Although the current period translation adjustment for the second quarter of 2009 is positive, the cumulative translation adjustment at 30 June 2009 still will be negative, but the amount now will be only €1,500.

3.2. Translation Methods

The two approaches to translating foreign currency financial statements described in the previous section are known as (1) the current rate method (all assets and liabilities are translated at the current exchange rate), and (2) the monetary/nonmonetary method (only monetary assets and liabilities are translated at the current exchange rate). A variation of the monetary/nonmonetary method requires not only monetary assets and liabilities but also nonmonetary assets and liabilities that are measured at their current value on the balance sheet date to be translated at the current exchange rate. This variation of the monetary/nonmonetary method sometimes is referred to as the temporal method. The basic idea underlying the temporal method is that assets and liabilities should be translated in such a way that the measurement basis (either current value or historical cost) in the foreign currency is preserved after translating to the parent’s presentation currency. To achieve this objective, assets and liabilities carried on the foreign currency balance sheet at a current value should be translated at the current exchange rate, and assets and liabilities carried on the foreign currency balance sheet at historical costs should be translated at historical exchange rates. Although neither the IASB nor the FASB specifically refer to translation methods by name, the procedures required by IFRS and U.S. GAAP in translating foreign currency financial statements essentially require the use of either the current rate or the temporal method.

Which method is appropriate for an individual foreign entity depends on that entity’s functional currency. As noted earlier, the functional currency is the currency of the primary economic environment in which an entity operates. A foreign entity’s functional currency can be either the parent’s presentation currency or another currency, typically the currency of the country in which the foreign entity is located. Exhibit 15-3 lists the factors that IAS 21 indicates should be considered in determining a foreign entity’s functional currency. Although not identical, SFAS 52 provides similar indicators for determining a foreign entity’s functional currency.

When the functional currency indicators listed in Exhibit 15-3 are mixed and the functional currency is not obvious, IAS 21 indicates that management should use its best judgment in determining the functional currency. However, in this case, indicators 1 and 2 should be given priority over indicators 3 through 9.

Exhibit 15-3 Factors Considered in Determining the Functional Currency

In accordance with IAS 21, The Effects of Changes in Foreign Exchange Rates, the following factors should be considered in determining an entity’s functional currency:

1. The currency that influences sales prices for goods and services.

2. The currency of the country whose competitive forces and regulations mainly determine the sales price of its goods and services.

3. The currency that mainly influences labor, material, and other costs of providing goods and services.

4. The currency in which funds from financing activities are generated.

5. The currency in which receipts from operating activities are usually retained.

Additional factors to consider in determining whether the foreign entity’s functional currency is the same as the parent’s are:

6. Whether the activities of the foreign operation are an extension of the parent’s or are carried out with a significant amount of autonomy.

7. Whether transactions with the parent are a large or a small proportion of the foreign entity’s activities.

8. Whether cash flows generated by the foreign operation directly affect the cash flow of the parent and are available to be remitted to the parent.

9. Whether operating cash flows generated by the foreign operation are sufficient to service existing and normally expected debt or whether the foreign entity will need funds from the parent to service its debt.

The following three steps outline the functional currency approach required by both IFRS and U.S. GAAP in translating foreign currency financial statements into the parent’s presentation currency:

1. Identify the functional currency of the foreign entity.

2. Translate foreign currency balances into the foreign entity’s functional currency.

3. Use the current exchange rate to translate the foreign entity’s functional currency balances into the parent’s presentation currency, if they are different.

To illustrate how this approach is applied, consider a U.S. parent company with a Mexican subsidiary that keeps its accounting records in Mexican pesos. Assume that the vast majority of the subsidiary’s transactions are carried out in Mexican pesos but it also has an account payable in Guatemalan quetzals. In applying the three steps, the U.S. parent company first determines that the Mexican peso is the functional currency of the Mexican subsidiary. Second, the Mexican subsidiary translates its foreign currency balances, that is, the Guatemalan quetzal account payable, into Mexican pesos using the current exchange rate. In step 3, the Mexican peso financial statements (including the translated account payable) are translated into U.S. dollars using the current rate method.

Now assume that the primary operating currency of the Mexican subsidiary is the U.S. dollar, which thus is identified as the Mexican subsidiary’s functional currency. In that case, in addition to the Guatemalan quetzal account payable, all of the subsidiary’s accounts that are denominated in Mexican pesos also are considered to be foreign currency balances (because they are not denominated in the subsidiary’s functional currency, which is the U.S. dollar). Along with the Guatemalan quetzal balance, each of the Mexican peso balances must be translated into U.S. dollars as if the subsidiary kept its books in U.S. dollars. Assets and liabilities carried at current value in Mexican pesos are translated into U.S. dollars using the current exchange rate, and assets and liabilities carried at historical cost in Mexican pesos are translated into U.S. dollars using historical exchange rates. After completing this step, the Mexican subsidiary’s financial statements are stated in terms of U.S. dollars, which is both the subsidiary’s functional currency and the parent’s presentation currency. As a result, there is no need to apply step 3.

The procedures to be followed in applying the functional currency approach embodied in IFRS and U.S. GAAP are described in more detail in the following two sections.

3.2.1. Foreign Currency is the Functional Currency

In most cases, a foreign entity will primarily operate in the currency of the country where it is located, which will be different from the currency in which the parent company presents its financial statements. For example, the Japanese subsidiary of a French parent company is likely to have the Japanese yen as its functional currency, whereas the French parent company must prepare consolidated financial statements in euros. When a foreign entity has a functional currency that is different from the parent’s presentation currency, the foreign entity’s foreign currency financial statements are translated into the parent’s presentation currency using the following procedures:

- All assets and liabilities are translated at the current exchange rate at the balance sheet date.

- Stockholders’ equity accounts are translated at historical exchange rates.

- Revenues and expenses are translated at the exchange rate that existed when the transactions took place. For practical reasons, a rate that approximates the exchange rates at the dates of the transactions, such as an average exchange rate, may be used.

These procedures essentially describe the current rate method.

Under both IAS 21 and SFAS 52, when the current rate method is used, the cumulative translation adjustment needed to keep the translated balance sheet in balance is reported as a separate component of stockholders’ equity.

The basic concept underlying the current rate method is that the entire investment in a foreign entity is exposed to translation gain or loss. Therefore, all assets and all liabilities must be revalued at each successive balance sheet date. But the net translation gain or loss that results from this procedure is unrealized and will be realized only when the entity is sold. In the meantime, the unrealized translation gain or loss that accumulates over time is deferred on the balance sheet as a separate component of stockholders’ equity. When a specific foreign entity is sold, the cumulative translation adjustment related to that entity is reported as a realized gain or loss in net income.

The current rate method results in a net asset balance sheet exposure (except in the rare case in which an entity has negative stockholders’ equity):

Items Translated at Current Exchange Rate

![]()

When the foreign currency increases in value (strengthens), application of the current rate method results in an increase in the positive cumulative translation adjustment (or a decrease in the negative cumulative translation adjustment) reflected in stockholders’ equity. When the foreign currency decreases in value (weakens), the current rate method results in a decrease in the positive cumulative translation adjustment (or increase in the negative cumulative translation adjustment) in stockholders’ equity.

3.2.2. Parent’s Presentation Currency is the Functional Currency

In some cases, a foreign entity might have the parent’s presentation currency as its functional currency. For example, a German-based manufacturer might have a 100 percent–owned distribution subsidiary in Switzerland that primarily uses the euro in its day-to-day operations. But as a Swiss company, the subsidiary is required to record its transactions and keep its books in Swiss francs. In that situation, the subsidiary’s Swiss franc financial statements must be translated into euros as if the subsidiary’s transactions had originally been recorded in euros. SFAS 52 refers to this process as remeasurement. IAS 21 does not refer to this process as remeasurement, but instead describes this situation as “reporting foreign currency transactions in the functional currency.” To achieve the objective of translating to the parent’s presentation currency as if the subsidiary’s transactions had been recorded in that currency, the following procedures are used:

1. a. Monetary assets and liabilities are translated at the current exchange rate.

b. Nonmonetary assets and liabilities measured at historical cost are translated at historical exchange rates.

c. Nonmonetary assets and liabilities measured at current value are translated at the exchange rate at the date when the current value was determined.

2. Stockholders’ equity accounts are translated at historical exchange rates.

3. a. Revenues and expenses, other than those expenses related to nonmonetary assets (as explained in 3.b), are translated at the exchange rate that existed when the transactions took place (for practical reasons, average rates may be used).

b. Expenses related to nonmonetary assets, such as cost of goods sold (inventory), depreciation (fixed assets), and amortization (intangible assets), are translated at the exchange rates used to translate the related assets.

These procedures essentially describe the temporal method.

Under the temporal method, companies must keep record of the exchange rates that exist when nonmonetary assets (inventory, prepaid expenses, fixed assets, and intangible assets) are acquired, because these assets (normally measured at historical cost) are translated at historical exchange rates. Keeping track of the historical exchange rates for these assets is not necessary under the current rate method. Translating these assets (and their related expenses) at historical exchange rates complicates application of the temporal method.

The historical exchange rates used to translate inventory (and cost of goods sold) under the temporal method will differ depending on the cost flow assumption—first in, first out (FIFO), last in, first out (LIFO), or average cost—used to account for inventory. Ending inventory reported on the balance sheet is translated at the exchange rate that existed when the inventory assumed to still be on hand at the balance sheet date (using FIFO or LIFO) was acquired. If FIFO is used, ending inventory is assumed to be composed of the most recently acquired items and thus inventory will be translated at relatively recent exchange rates. If LIFO is used, ending inventory is assumed to consist of older items and thus inventory will be translated at older exchange rates. The weighted average exchange rate for the year is used when inventory is carried at weighted average cost. Similarly, cost of goods sold is translated using the exchange rates that existed when the inventory items assumed to have been sold during the year (using FIFO or LIFO) were acquired. If weighted average cost is used to account for inventory, cost of goods sold will be translated at the weighted average exchange rate for the year.

Under both IAS 21 and SFAS 52, when the temporal method is used, the translation adjustment needed to keep the translated balance sheet in balance is reported as a gain or loss in net income. SFAS 52 refers to these as remeasurement gains and losses.

The basic assumption supporting the recognition of a translation gain or loss in income when the temporal method is used is that if the foreign entity primarily uses the parent’s currency in its day-to-day operations, then the foreign entity’s monetary items that are denominated in a foreign currency generate translation gains and losses that will be realized in the near future and thus should be reflected in current net income.

The temporal method generates either a net asset or a net liability balance sheet exposure, depending on whether assets translated at the current exchange rate, that is, monetary assets and nonmonetary assets measured on the balance sheet date at current value (exposed assets), are greater than or less than liabilities translated at the current exchange rate, that is, monetary liabilities and nonmonetary liabilities measured on the balance sheet date at current value (exposed liabilities):

Items Translated at Current Exchange Rate

![]()

Most liabilities are monetary liabilities. Only cash and receivables are monetary assets, and nonmonetary assets generally are measured at their historical cost. As a result, liabilities translated at the current exchange rate (exposed liabilities) often exceed assets translated at the current exchange rate (exposed assets), which results in a net liability balance sheet exposure when the temporal method is applied.

3.2.3. Translation of Retained Earnings

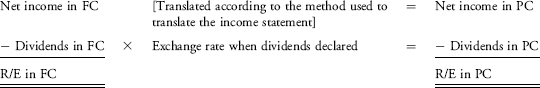

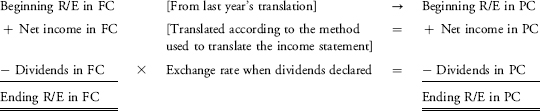

Stockholders’ equity accounts are translated at historical exchange rates under both the current rate and the temporal methods. This creates somewhat of a problem in translating retained earnings (R/E), which is the accumulation of previous years’ income less dividends over the life of the company. At the end of the first year of operations, foreign currency (FC) retained earnings are translated into the parent’s currency (PC) as follows:

Retained earnings in parent currency at the end of the first year becomes the beginning retained earnings in parent currency for the second year, and the translated retained earnings in the second year (and subsequent years) is then calculated in the following manner:

Exhibit 15-4 summarizes the translation rules as discussed in Sections 3.2.1 and 3.2.2.

EXHIBIT 15-4 Rules for the Translation of a Foreign Subsidiary’s Foreign Currency Financial Statements into the Parent’s Presentation Currency under IFRS and U.S. GAAP

| Foreign Subsidiary’s Functional Currency | ||

| Foreign Currency | Parent’s Presentation Currency | |

| Translation method: | Current Rate Method | Temporal Method |

| Exchange rate at which financial statement items are translated from the foreign subsidiary’s bookkeeping currency to the parent’s presentation currency: | ||

| Assets | ||

| Monetary, e.g., cash; receivables | Current rate | Current rate |

| Nonmonetary | ||

|

Current rate | Current rate |

|

Current rate | Historical rates |

| Liabilities | ||

| Monetary, e.g., accounts payable; accrued expenses; long-term debt; deferred income taxes | Current rate | Current rate |

| Nonmonetary | ||

|

Current rate | Current rate |

|

Current rate | Historical rates |

| Equity | ||

| Other than retained earnings | Historical rates | Historical rates |

| Retained earnings | Beginning balance plus translated net income less dividends translated at historical rate | Beginning balance plus translated net income less dividends translated at historical rate |

| Revenues | Average rate | Average rate |

| Expenses | ||

| Most expenses | Average rate | Average rate |

| Expenses related to assets translated at historical exchange rate, e.g., cost of goods sold; depreciation; amortization | Average rate | Historical rates |

| Treatment of the translation adjustment in the parent’s consolidated financial statements | Accumulated as a separate component of equity | Included as gain or loss in net income |

3.2.4. Highly Inflationary Economies

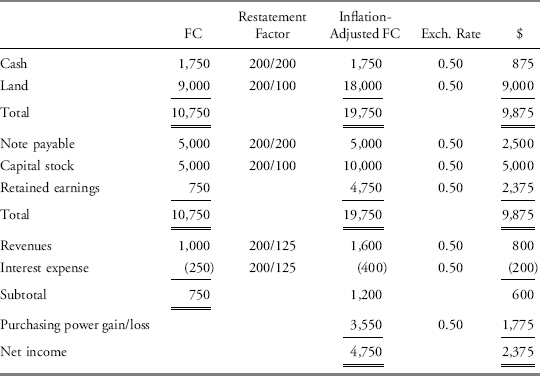

When a foreign entity is located in a highly inflationary economy, the entity’s functional currency is irrelevant in determining how to translate its foreign currency financial statements into the parent’s presentation currency. IAS 21 requires that the financial statements of the foreign entity first be restated for local inflation using the procedures outlined in IAS 29, “Financial Reporting in Hyperinflationary Economies.” Then, the inflation-restated foreign currency financial statements are translated into the parent’s presentation currency using the current exchange rate.

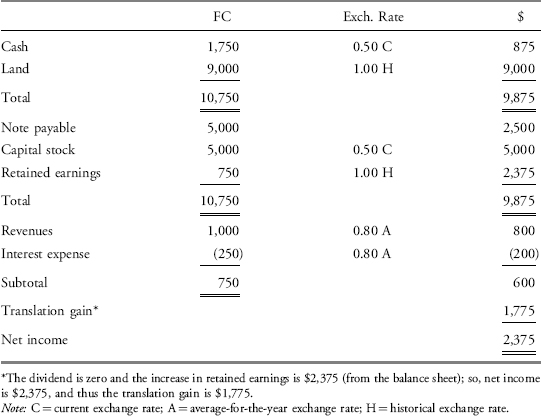

U.S. GAAP requires a very different approach for translating the foreign currency financial statements of foreign entities located in highly inflationary economies. SFAS 52 does not allow restatement for inflation, but instead requires the temporal method to translate financial statements kept in a highly inflationary currency. However, despite the use of the temporal method, the resulting translation adjustment is included as a gain or loss in determining net income.

SFAS 52 defines a highly inflationary economy as one in which the cumulative three-year inflation rate exceeds 100 percent. This equates to an average of approximately 26 percent per year. IAS 21 does not provide a specific definition of high inflation, but IAS 29 does indicate that a cumulative inflation rate approaching or exceeding 100 percent over three years would be one indicator of hyperinflation. If a country in which a foreign entity is located ceases to be classified as highly inflationary, the functional currency of that foreign entity must be identified to determine the appropriate method for translating the entity’s foreign currency financial statements.

The FASB initially proposed that companies restate for inflation and then translate the financial statements, but this approach met with stiff resistance from U.S. multinational corporations. By requiring the temporal method, SFAS 52 ensures that companies avoid a “disappearing plant problem” that exists when the current rate method is used in a country with high inflation. In a highly inflationary economy, as the local currency loses purchasing power within the country, it also tends to weaken in value in relation to other currencies. Translating the historical cost of assets such as land and buildings at progressively lower exchange rates causes these assets to slowly disappear from the parent company’s consolidated financial statements. Example 15-4 demonstrates the effect of three different translation approaches when books are kept in the currency of a highly inflationary economy.

EXAMPLE 15-4 Foreign Currency Translation in a Highly Inflationary Economy

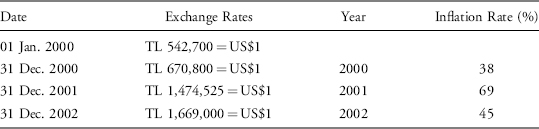

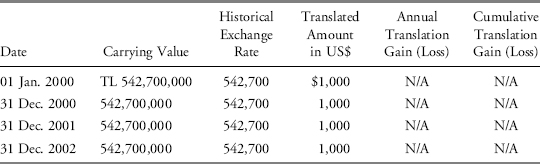

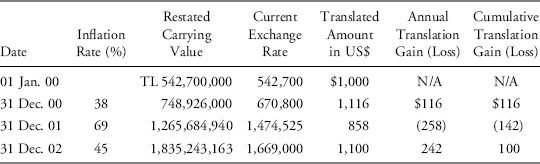

Turkey was one of the few remaining highly inflationary countries at the beginning of the 21st century. Annual inflation rates and selected exchange rates between the Turkish lira (TL) and U.S. dollar during the period 2000-2002 were as follows:

Assume that a U.S.-based company established a subsidiary in Turkey on 1 January 2000. The U.S. parent sent the subsidiary US$1,000 on 1 January 2000 to purchase a piece of land at a cost of TL 542,700,000 (TL 542,700/US$ × US$1,000 = TL 542,700,000). Assuming no other assets or liabilities, what are the annual and cumulative translation gains or losses that would be reported under each of three possible translation approaches?

Solution:

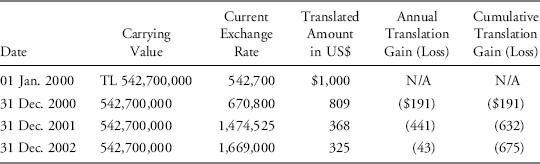

Approach 1: Translate Using the Current Rate Method

The historical cost of the land is translated at the current exchange rate, which results in a new translated amount at each balance sheet date.

At the end of three years, land that was originally purchased with US$1,000 would be reflected on the parent’s consolidated balance sheet at US$325 (and remember that land is not a depreciable asset). A cumulative translation loss of US$675 would be reported as a separate component of stockholders’ equity on 31 December 2002. Because this method accounts for adjustments in exchange rates but does not account for likely changes in the local currency values of assets, it does a poor job accurately reflecting the economic reality of situations such as the one in our example. That is the major reason this approach is not acceptable under either IFRS or U.S. GAAP.

Approach 2: Translate Using the Temporal Method (SFAS 52)

The historical cost of land is translated using the historical exchange rate, which results in the same translated amount at each balance sheet date.

Under this approach, land continues to be reported on the parent’s consolidated balance sheet at its original cost of US$1,000 each year. There is no translation gain or loss related to balance sheet items translated at historical exchange rates. This approach is required by SFAS 52 and ensures that nonmonetary assets do not disappear from the translated balance sheet.

Approach 3: Restate for Inflation/Translate Using Current Exchange Rate (IAS 21)

The historical cost of the land is restated for inflation and then the inflation-adjusted historical cost is translated using the current exchange rate.

Under this approach, land is reported on the parent’s 31 December 2002 consolidated balance sheet at US$1,100 with a cumulative, unrealized gain of US$100. Although the cumulative translation gain on 31 December 2002 is unrealized, it could have been realized if (1) the land had appreciated in TL value by the rate of local inflation, (2) the Turkish subsidiary sold the land for TL 1,835,243,163, and (3) the sale proceeds were converted into US$1,100 at the current exchange rate on 31 December 2002.

This approach is required by IAS 21. It is the approach that perhaps best represents economic reality in the sense that it reflects both the likely change in the local currency value of the land as well as the actual change in the exchange rate.

3.3. Illustration of Translation Methods (Excluding Hyperinflationary Economies)

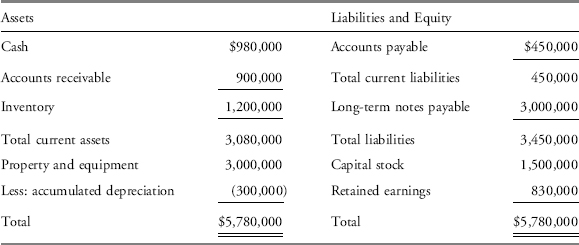

To demonstrate the procedures required by IAS 21 and SFAS 52 in translating foreign currency financial statements, assume that Interco is a European-based company that has the euro as its presentation currency. On 1 January 2008, Interco establishes a wholly owned subsidiary in Canada, Canadaco. In addition to Interco making an equity investment in Canadaco, a long-term note payable to a Canadian bank was negotiated to purchase property and equipment. The subsidiary begins operations with the following balance sheet in Canadian dollars (C$):

Canadaco Balance Sheet 1 January 2008 (in Canadian Dollars)

| Assets | |

| Cash | $1,500,000 |

| Property and equipment | 3,000,000 |

| $4,500,000 | |

| Liabilities and Equity | |

| Long-term note payable | $3,000,000 |

| Capital stock | 1,500,000 |

| $4,500,000 |

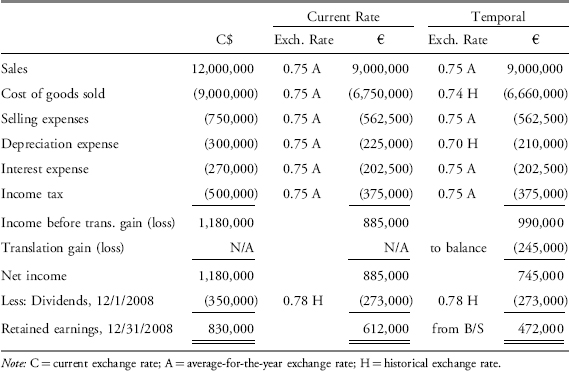

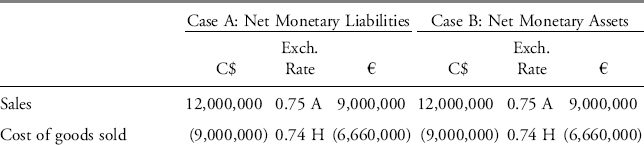

Canadaco purchases and sells inventory in 2008, generating net income of C$1,180,000, out of which C$350,000 in dividends are paid. The company’s income statement and statement of retained earnings for 2008 and balance sheet at 31 December 2008 follow:

Canadaco Income Statement and Statement of Retained Earnings 2008 (in Canadian Dollars)

| Sales | $12,000,000 |

| Cost of sales | (9,000,000) |

| Selling expenses | (750,000) |

| Depreciation expense | (300,000) |

| Interest expense | (270,000) |

| Income tax | (500,000) |

| Net income | 1,180,000 |

| Less: Dividends, 1 Dec. 2008 | (350,000) |

| Retained earnings, 31 Dec. 2008 | $830,000 |

Canadaco Balance Sheet 31 December 2008 (in Canadian Dollars)

Inventory is measured at historical cost on a FIFO basis.

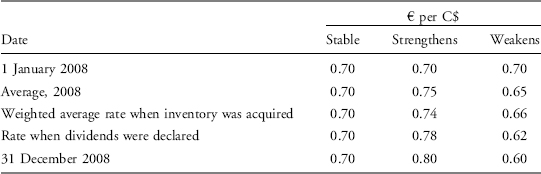

To translate Canadaco’s Canadian dollar financial statements into euros for consolidation purposes, the following exchange rate information was gathered:

| Date | € per C$ |

| 1 January 2008 | 0.70 |

| Average, 2008 | 0.75 |

| Weighted average rate when inventory was acquired | 0.74 |

| 1 December 2008 when dividends were declared | 0.78 |

| 31 December 2008 | 0.80 |

During 2008, the Canadian dollar strengthened steadily against the euro from an exchange rate of €0.70 at the beginning of the year to €0.80 at year-end.

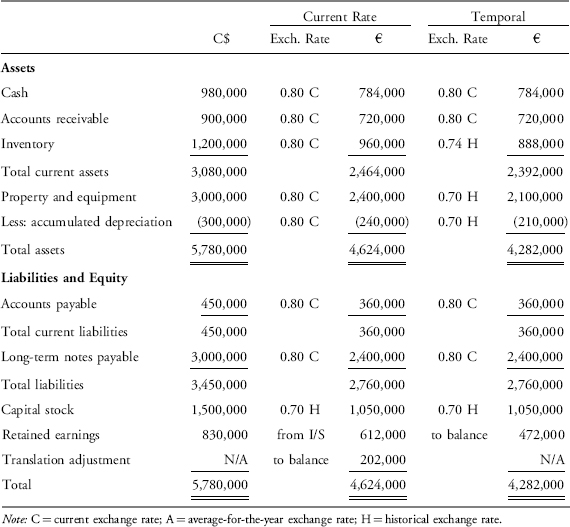

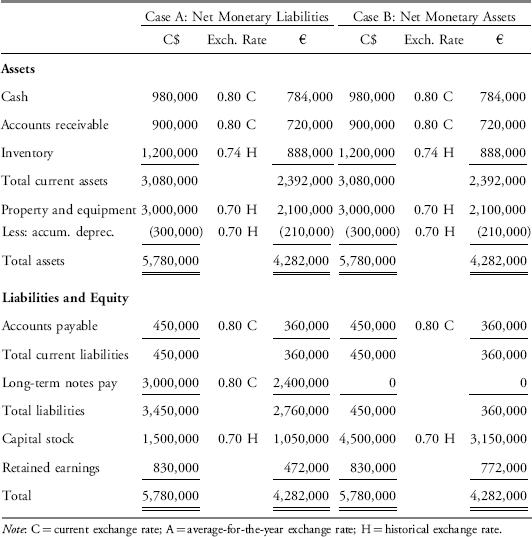

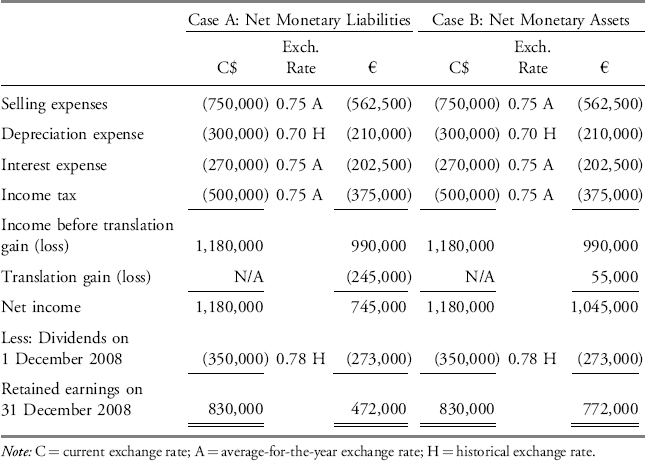

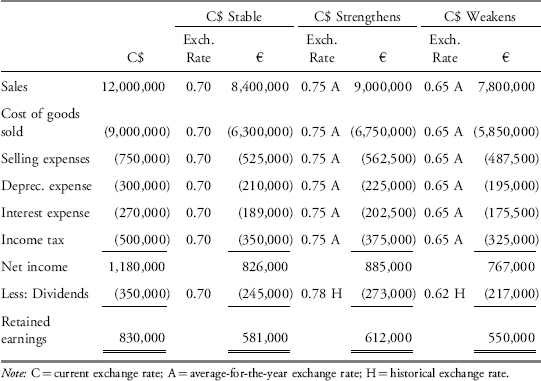

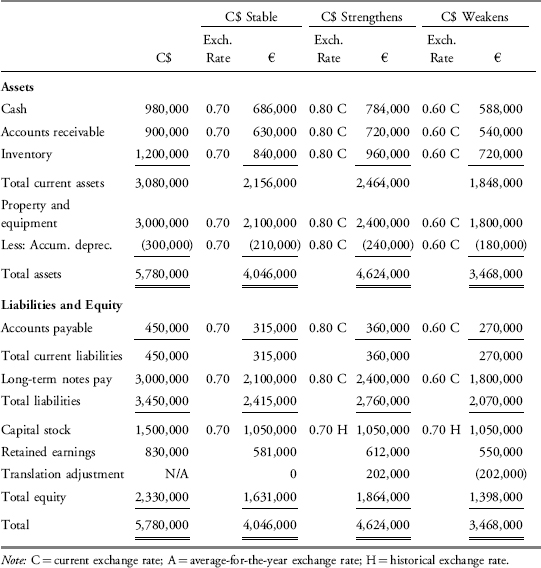

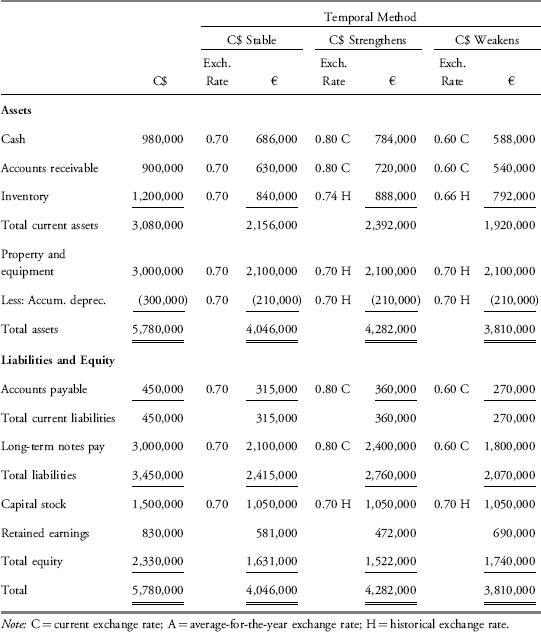

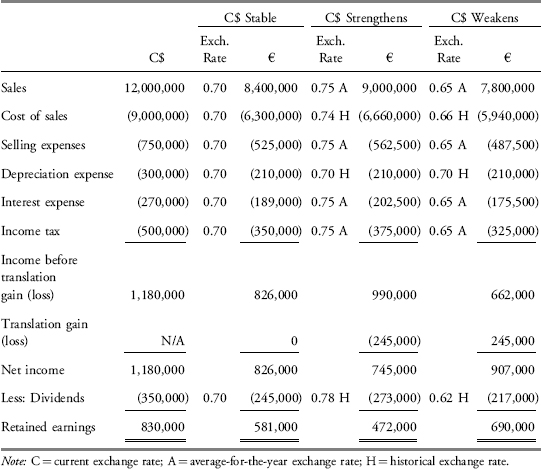

The translation worksheet following shows Canadaco’s translated financial statements under each of the two translation methods. Assume first that Canadaco’s functional currency is the Canadian dollar and therefore the current rate method must be used. The Canadian dollar income statement and statement of retained earnings are translated first. Income statement items for 2008 are translated at the average exchange rate for 2008 (€0.75), and dividends are translated at the exchange rate that existed when they were declared (€0.78). The ending balance in retained earnings at 31 December 2008 of €612,000 is transferred to the C$ balance sheet. The remaining balance sheet accounts are then translated. Assets and liabilities are translated at the current exchange rate on the balance sheet date of 31 December 2008 (€0.80), and the capital stock account is translated at the historical exchange rate (€0.70) that existed on the date that Interco made the capital contribution. A positive translation adjustment of €202,000 is needed as a balancing amount, which is reported in the stockholders’ equity section of the balance sheet.

If instead Interco determines that Canadaco’s functional currency is the euro, the parent’s presentation currency, the temporal method must be applied as shown in the far right columns of the table. The differences in procedure from the current rate method are that inventory, property, and equipment (and accumulated depreciation), as well as their related expenses (cost of goods sold and depreciation), are translated at the historical exchange rates that existed when the assets were acquired: €0.70 in the case of property and equipment, and €0.74 for inventory. The balance sheet is translated first, with €472,000 determined as the amount of retained earnings needed to keep the balance sheet in balance. This amount is transferred to the income statement and statement of retained earnings as the ending balance in retained earnings at 31 December 2008. Income statement items then are translated, with cost of goods sold and depreciation expense being translated at historical exchange rates. A negative translation adjustment of €245,000 is determined as the amount that is needed to arrive at the ending balance in retained earnings of €472,000, and is reported as a translation loss on the income statement.

The positive translation adjustment under the current rate method can be explained by the fact that Canadaco has a net asset balance sheet exposure (total assets exceed total liabilities) during 2008 and the Canadian dollar strengthened against the euro. The negative translation adjustment (translation loss) under the temporal method is due to the fact that Canadaco has exposed liabilities (accounts payable plus notes payable) that exceed exposed assets (cash plus receivables) during 2008 when the Canadian dollar strengthened against the euro.

Canadaco Income Statement and Statement of Retained Earnings 2008

Canadaco Balance Sheet 31 December 2008

3.4. Translation Analytical Issues

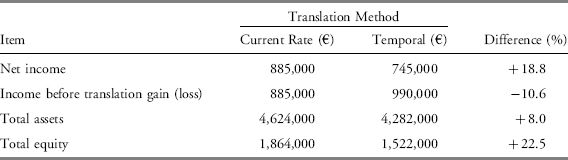

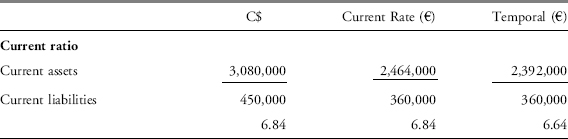

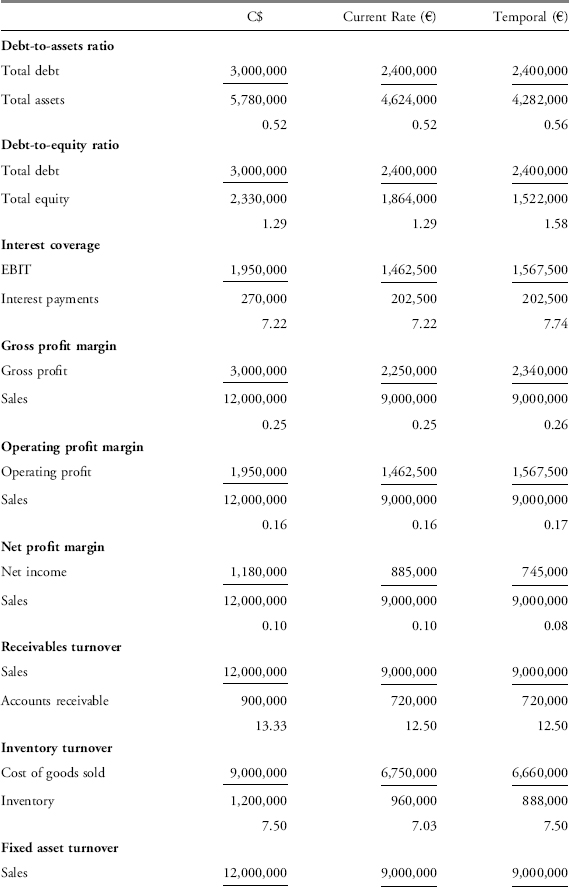

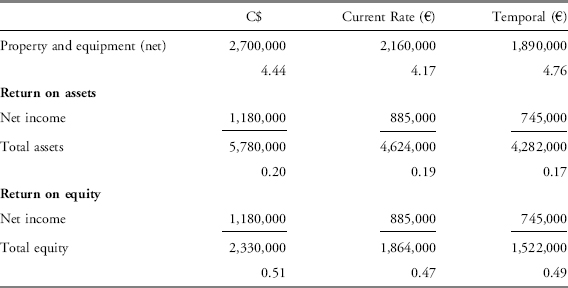

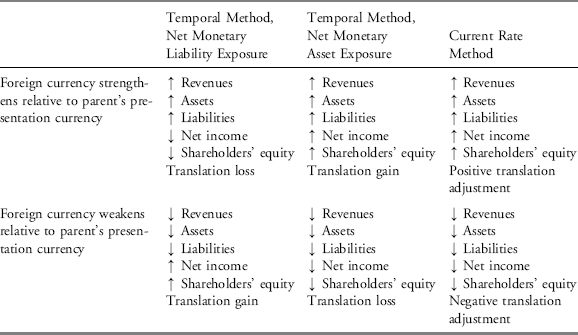

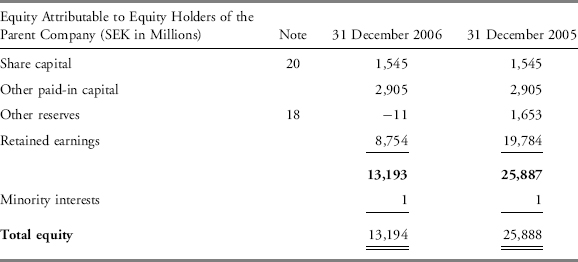

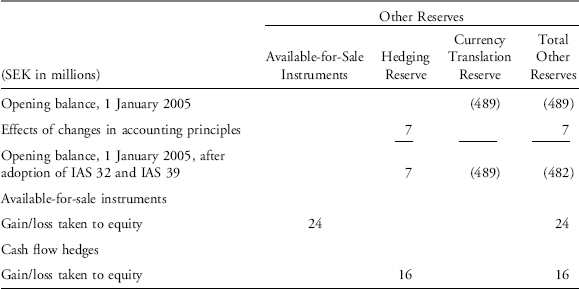

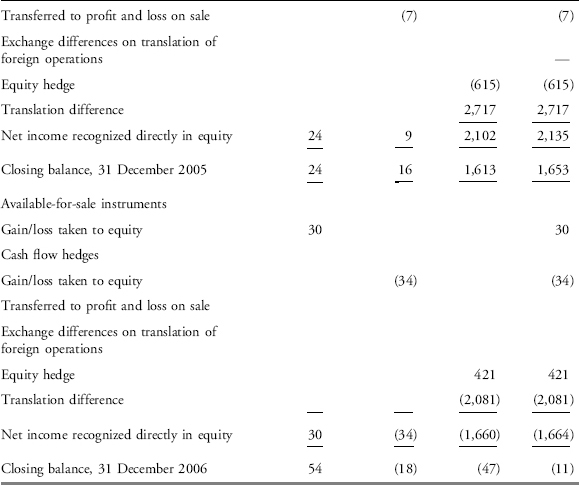

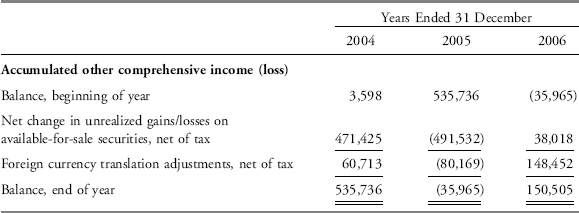

The two different translation methods used to translate Canadaco’s C$ financial statements into euros result in very different amounts that will be included in Interco’s consolidated financial statements. The chart following summarizes some of these differences: