CHAPTER 13

EMPLOYEE COMPENSATION: POSTEMPLOYMENT AND SHARE-BASED

After completing this chapter, you will be able to do the following:

- Describe the types of postemployment benefit plans and the implications for financial reports.

- Explain and calculate measures of a defined benefit pension obligation (i.e., present value of the defined benefit obligation and projected benefit obligation) and net pension liability (or asset).

- Describe the components of a company’s defined benefit pension expense.

- Explain and calculate the impact of a defined benefit plan’s assumptions on the defined benefit obligation and periodic expense.

- Calculate and explain the effects on financial statements of adjusting for items of pension and other postemployment benefits that are reported in the notes to the financial statements.

- Interpret pension plan note disclosures including cash flow related information.

- Evaluate the underlying economic liability (or asset) of a company’s pension and other postemployment benefits.

- Calculate the underlying economic pension expense (income) and other postemployment expense (income) based on disclosures.

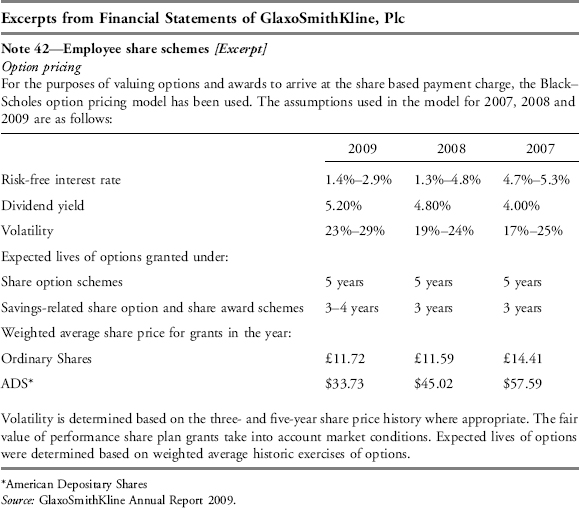

- Explain issues involved in accounting for share-based compensation.

- Explain the impact on financial statements of the accounting for stock grants and stock options, and the importance of companies’ assumptions in valuing these grants and options.

This chapter covers two complex aspects of employee compensation: postemployment (retirement) benefits and share-based compensation. Retirement benefits include pensions and other postemployment benefits such as health insurance. Examples of share-based compensation are stock options and stock grants.

A common issue underlying both aspects of employee compensation is the difficulty in measuring the value of the compensation. One factor contributing to the difficulty is that employees earn the benefits in the periods that they provide service, but typically receive the benefits in future periods—so measurement requires a significant number of assumptions.

This chapter provides an overview of the methods companies use to estimate and measure the benefits they provide to their employees and how this information is reported in financial statements. There has been some convergence between international financial reporting standards (IFRS) and U.S. generally accepted accounting principles (U.S. GAAP) in the measurement and accounting treatment for pensions, other postemployment benefits, and share-based compensation; but some differences remain. Although this chapter focuses primarily on IFRS, instances where U.S. GAAP significantly differ are discussed.

The chapter is organized as follows: Section 2 addresses pensions and other postemployment benefits, and Section 3 covers share-based compensation with a primary focus on the accounting for and analysis of stock options. A summary and practice problems conclude the chapter.

2. PENSIONS AND OTHER POSTEMPLOYMENT BENEFITS

This section discusses the accounting and reporting of pensions and other postemployment benefits by the companies that provide these benefits (accounting and reporting by pension and other retirement funds are not covered in this chapter). Under IFRS, IAS 19, Employee Benefits, provides the principal source of guidance in accounting for pensions and other postemployment benefits. Under U.S. GAAP, the guidance is spread across several sections of the FASB Codification.1

The discussion begins with an overview of the types of benefits and measurement issues involved, including the accounting treatment for defined contribution plans. It then continues with financial statement reporting of pension plans and other postemployment benefits including an overview of critical assumptions used to value these benefits. The section concludes with a discussion of evaluating defined benefit pension plan and other postemployment benefit disclosures.

2.1. Types of Postemployment Benefit Plans

Companies (sponsors) may offer various types of benefits to their employees following retirement, including pension plans, health care plans, medical insurance, and life insurance. Some of these benefits involve payments in the current period but many are promises of future benefits. The objectives of accounting for employee benefits is to measure the cost associated with providing these benefits and to recognize these costs in the sponsoring company’s financial statements during the employees’ periods of service. Complexity arises because the sponsoring company must make assumptions to estimate the value of future benefits. The assumptions required to estimate and recognize these future benefits can have a significant impact on the company’s reported performance and financial position. In addition, differences in assumptions can reduce comparability across companies.

Pension plans, as well as other postemployment benefits, may be either defined contribution plans or defined benefit plans. Under a defined contribution (DC) pension plan, specific (or agreed-upon) contributions are made to an employee’s pension plan. The agreed-upon amount is the pension expense. Typically, in a DC pension plan, an individual account is established for each participating employee. The accounts are generally invested through a financial intermediary such as an investment management company or an insurance company. The employees and the employer may each contribute to the plan. After the employer makes its agreed-upon contribution to the plan on behalf of an employee—generally in the same period in which the employee provides the service—the employer has no obligation to make payments beyond this amount. The future value of the plan’s assets depends on the performance of the investments within the plan. Any gains or losses related to those investments accrue to the employee. Therefore, in DC pension plans, the employee bears the risk that plan assets will not be sufficient to meet future needs. The impact on the company’s financial statements of DC pension plans is easily assessed, because the company has no obligations beyond the required contributions.

In contrast to DC pension plans, defined benefit (DB) pension plans are essentially promises by the employer to pay a defined amount of pension in the future. As part of total compensation, the employee works in the current period in exchange for a pension to be paid after retirement. In a DB pension plan, the amount of pension benefit to be provided is defined, usually by reference to age, years of service, compensation, and so forth. For example, a DB pension plan may provide for the retiree to be paid, annually until death, an amount equal to 1 percent of the final year’s salary times the number of years of service. The future pension payments represent a liability or obligation of the company. To measure this obligation, the employer must make various actuarial assumptions (employee turnover, average retirement age, life expectancy after retirement) and computations. The assumptions should be evaluated for their reasonableness, and the impact of the assumptions on the financial reports of the company should be analyzed.

Under IFRS and U.S. GAAP, all plans for pensions and other postemployment benefits other than those explicitly structured as DC plans are classified as DB plans.2 DB plans include both formal plans and those informal arrangements that create a constructive obligation by the employer to its employees.3 The employer must estimate the total cost of the benefits promised and then allocate these costs to the periods in which the employees provide service. This estimation and allocation further increases the complexity of pension reporting because the timing of cash flows (contributions into the plan and payments from the plan) can differ significantly from the timing of accrual-basis reporting. The accrual-basis reporting is based on when the services are rendered and the benefits earned.

Most DB pension plans are funded through a separate legal entity, typically a pension trust, and the assets of the trust are used to make the payments to retirees. The sponsoring company is responsible for making contributions to the plan. The company also must ensure that there are sufficient assets in the plan to pay the ultimate benefits promised to plan participants. Regulatory requirements usually specify minimum funding levels for DB pension plans, but those requirements vary by country. The funded status of a pension plan—overfunded or underfunded—refers to whether the amount of assets in the pension trust is greater than or less than the estimated liability. If the amount of assets in the DB pension trust exceeds the present value of the estimated liability, the DB pension plan is said to be overfunded; conversely, if the amount of assets in the pension trust is less than the estimated liability, the plan is said to be underfunded. Because the company has promised a defined amount of benefit to the employees, it is obligated to make those pension payments when they are due regardless of whether the pension plan assets generate sufficient returns to provide the benefits. In other words, the company bears the investment risk. Many companies are reducing the use of DB pension plans because of this.

Similar to DB pension plans, other postemployment benefits (OPB) are promises by the company to pay benefits in the future, such as life insurance premiums and all or part of health care insurance for its retirees. OPB are typically classified as DB plans with accounting treatment similar to DB pension plans. However, the complexity in reporting for OPB may be even greater than for DB pension plans because of the need to estimate future increases in costs, such as health care, over a long time horizon. Unlike DB pension plans, however, companies may not be required by regulation to fund an OPB in advance to the same degree as DB pension plans. This is partly because governments, through some means, often insure DB pension plans but not OPB, partly because OPB may represent a much smaller financial liability, and partly because OPB are often easier to eliminate should the costs become burdensome. It is important that an analyst determine what OPB are offered by a company and the obligation these represent.

Types of postemployment benefits offered by employers differ across countries. For instance, in countries where government-sponsored universal health care plans exist (such as Germany, France, Canada, Brazil, Mexico, New Zealand, South Africa, India, Israel, Bhutan, and Singapore), companies are less likely to provide postretirement health care benefits to employees. The extent to which companies offer DC or DB pension plans also vary by country.

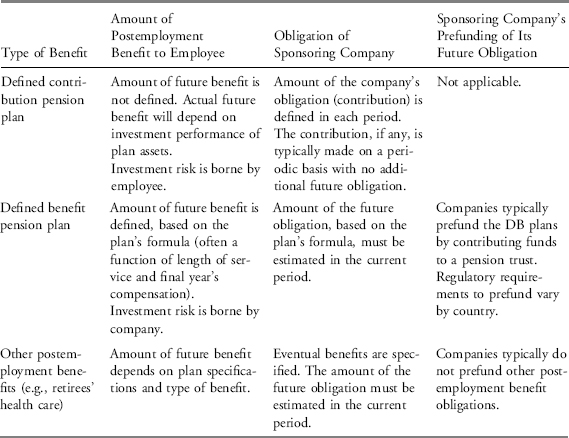

Exhibit 13-1 summarizes these three types of postemployment benefits.

EXHIBIT 13-1 Types of Postemployment Benefits

The following sections provide additional detail on how DB pension plan liabilities and periodic costs are measured, the financial statement impact of reporting pension and other postemployment benefits, and how disclosures in the notes to the financial statements can be used to gain insights about the underlying economics of a company’s defined benefit plans. Section 2.2 describes how a DB pension plan’s obligation is estimated and the key inputs into and assumptions behind the estimate. Section 2.3 describes financial statement reporting of pension and OPB plans and demonstrates the calculation of defined benefit obligations and current costs and the effects of assumptions. Section 2.4 describes disclosures in financial reports about pension and OPB plans. These include disclosures about assumptions that can be useful in analyzing and comparing pension and OPB plans within and among companies. The disclosures are also useful in assessing the underlying economic pension liability (or asset) and expense (or income).

2.2. Measuring a Defined Benefit Pension Plan’s Obligations

Both IFRS and U.S. GAAP measure the pension obligation as the present value of future benefits earned by employees for service provided to date. The obligation is called the present value of the defined benefit obligation (PVDBO) under IFRS and the projected benefit obligation (PBO) under U.S. GAAP.4 This measure is defined as “the present value, without deducting any plan assets, of expected future payments required to settle the obligation arising from employee service in the current and prior periods” under IFRS and “the actuarial present value as of a date of all benefits attributed by the pension benefit formula to employee service rendered prior to that date” under U.S. GAAP. In the reminder of this chapter, the term “pension obligation” will be used to generically refer to PVDBO and PBO.

In determining the pension obligation, a company estimates the future benefits it will pay. To estimate the future benefits, the company must make a number of assumptions5 such as future compensation increases and levels, discount rates, and expected vesting rate. For instance, an estimate of future compensation is made if the pension benefit formula is based on future compensation levels (examples include pay-related, final-pay, final-average-pay, or career-average-pay plans). The expected annual increase in compensation over the employee service period can have a significant impact on the defined benefit obligation. The determination of the benefit obligation implicitly assumes that the company will continue to operate in the future (the “going concern assumption”) and recognizes that benefits will increase with future compensation increases.

Another key assumption is the discount rate—the interest rate used to calculate the present value of the future benefits. This rate is based on current rates of return on high quality corporate bonds (or government bonds in the absence of a deep market in corporate bonds) with currency and durations consistent with the currency and durations of the benefits. Under both DB and DC pension plans, the benefits that employees earn may be conditional on remaining with the company for a specified period of time. “Vesting” refers to a provision in pensions plans whereby an employee gains rights to future benefits only after meeting certain criteria such as a prespecified number of years of service. If the employee leaves the company before meeting the criteria, they may be entitled to none or a portion of the benefits they have earned up until that point. However, once the employee has met the vesting requirements, they are entitled to receive the benefits they have earned in prior periods (i.e., when the employee has become vested, benefits are not forfeited if the employee leaves the company). In measuring the defined benefit obligation, the company considers the probability that some employees may not satisfy the vesting requirements (i.e., may leave before the vesting period) and uses this probability to calculate the current service cost and the present value of the obligation. Current service cost is the increase in the present value of a defined benefit obligation as a result of employee service in the current period. Current service cost is not the only cause of change in the present value of a defined benefit obligation.

The estimates and assumptions about future salary increases, discount rate, and expected vesting rate can change. Of course, any changes in these estimates and assumptions will change the estimated pension obligation. If the changes increase the obligation, the increase is referred to as an actuarial loss. If the changes decrease the obligation, the change is referred to as an actuarial gain. Section 2.3.3 further discusses estimates and assumptions and the effect on the pension obligation and expense.

2.3. Financial Statement Reporting of Pension Plans and Other Postemployment Benefits

Sections 2.3.1 to 2.3.3 describe how pension plans and other postemployment benefits are reported in the financial statements of the sponsoring company and how assumptions affect the amounts reported. Disclosures related to pensions plans and OPB are described in Section 2.4.

2.3.1. Defined Contribution Pension Plans

The accounting treatment for defined contribution pension plans is relatively simple. From a financial statement perspective, the employer’s obligation for contributions into the plan, if any, is recorded as an expense on the income statement. Because the employer’s obligation is limited to a defined amount that typically equals its contribution, no significant pension related liability accrues on the balance sheet. An accrual (current liability) is recognized at the end of the reporting period only for any unpaid contributions.

2.3.2. Defined Benefit Pension Plans

The accounting treatment for defined benefit pension plans is more complex, primarily because of the complexities of measuring the pension obligation and expense. U.S. GAAP takes a simpler approach to measuring the amount reported on the balance sheet; for this reason, U.S. GAAP is discussed first in the next section on balance sheet presentation.

2.3.2.1. Balance Sheet Presentation

Under U.S. GAAP, a pension plan’s funded status is reported on the balance sheet. The funded status is determined by netting the pension obligation against the fair value of the pension plan assets. If the pension obligation exceeds the pension plan assets, then a liability equal to the net pension obligation or underfunded pension obligation is reported. If the plan assets exceed the pension obligation, then an asset equal to the overfunded pension obligation is reported.

Similarly under IFRS, a net amount is reported on the balance sheet but the net amount may differ from what would be reported under U.S. GAAP. First, IFRS does not immediately recognize all changes in the pension obligation due to plan amendments, which change the pension benefit for existing employees. These changes are referred to as past service costs (PSC) under IFRS and prior service costs under U.S. GAAP. Under IFRS, the change in the liability related to PSC for vested employees is recognized in the financial statements in the current period. Any PSC related to unvested employees is deferred and recognized as a liability as benefits vest. Therefore, the deferred PSC is not recorded in the balance sheet measure of the net pension liability (or net pension asset).

Second under IFRS, changes in pension obligations and plan assets that result from changing actuarial estimates and assumptions may or may not be fully recognized. A company may opt to fully recognize these changes, termed actuarial gains and losses, in the reported net pension liability (or net pension asset). A company’s other option is to defer recognizing the actuarial gains and losses (AGLs) until certain conditions are met. If a company chooses to fully recognize the AGLs, its reported net pension obligation (or net pension asset) is calculated as the pension obligation less fair value of pension plans assets less unrecognized past service costs. If a company chooses to defer recognizing the AGLs, its net pension liability (or net pension asset) is calculated as the pension obligation less fair value of pension plans assets less unrecognized past service costs plus unrecognized actuarial gains less unrecognized actuarial losses.6 Note that if the resulting number is positive a liability is reported, and if the resulting number is negative an asset is reported. Putting the preceding information in equation form, we see that:

![]()

The funded status is the amount reported on the balance sheet under U.S. GAAP as the net pension liability (asset).

![]()

The net pension liability (asset) after removing unrecognized past service costs and actuarial gains/losses is the amount reported on the balance sheet under IFRS, subject to limits on the amount of net plan assets that may be reported when a company defers AGLs. Specifically, IFRS restricts the amount of the net plan assets that can be reported on the balance sheet to the lower of:

- The pension obligation less fair value of pension plans assets less unrecognized past service costs plus unrecognized actuarial gains less unrecognized actuarial losses (as given earlier).

- The total of any cumulative unrecognized net actuarial losses and past service costs plus the present value of any economic benefits available in the form of refunds from the plan or reductions in future contributions to the plan.7

Under IFRS and U.S. GAAP, disclosures in the notes provide additional information about the net pension liability or asset reported on the balance sheet.

EXAMPLE 13-1 Determination of Amounts to Be Reported on the Balance Sheet

The following information pertains to a hypothetical company’s pension plan as of 31 December 2010:

- The present value of the company’s defined benefit obligation is 6,723 and the fair value of the pension plan’s assets is 4,880.

- The company has unrecognized actuarial losses of 255, and unrecognized past service costs of 170 related to unvested employees.

Calculate the amount the company would report as an asset or a liability and in equity on its 2010 balance sheet under each of the following:

1. IFRS if the company chooses to defer recognition of actuarial gains or losses

2. IFRS if the company chooses to recognize actuarial gains or losses

3. U.S. GAAP

Solution to 1: Under IFRS, if the company chooses to defer recognizing actuarial gains or losses, the company would report a net pension liability calculated as the total of the following amounts:

| Present value of defined benefit obligation | 6,723 |

| Unrecognized actuarial losses | (255) |

| Unrecognized past service costs | (170) |

| Fair value of plan assets | (4,880) |

| Net Pension Liability | 1,418 |

Actuarial losses and past service costs are included in the present value of defined benefit obligation and unrecognizing them reduces the amount of the liability reported.

Solution to 2: Under IFRS, if the company chooses to recognize actuarial gains or losses, the company would report a net pension liability calculated as the total of the following amounts:

| Present value of defined benefit obligation | 6,723 |

| Unrecognized past service costs | (170) |

| Fair value of plan assets | (4,880) |

| Net Pension Liability | 1,673 |

Solution to 3: Under U.S. GAAP, the company would report a pension liability of:

| Present value of defined benefit obligation | 6,723 |

| Fair value of plan assets | (4,880) |

| Net Pension Liability | 1,843 |

Under U.S. GAAP, the company would report the full underfunded status of its pension plan (i.e., the difference between the fair value of plan assets and the present value of the defined benefit obligation) as a liability. In addition, the company would report the following in accumulated other comprehensive income (a component of equity):

| Unrecognized actuarial losses | (255) |

| Unrecognized past service costs | (170) |

| Total | (425) |

This amount would be adjusted each period, as the unrecognized actuarial losses and past service costs are amortized to pension expense over the remaining service life of its employees.

EXAMPLE 13-2 Determination of the Amount of Pension Liability or Asset to Be Reported on the Balance Sheet

The following information pertains to a hypothetical company’s pension plan as of 31 December 2010:

- The present value of the company’s defined benefit obligation is 5,485 and the fair value of the pension plan assets is 5,998.

- The company has unrecognized actuarial losses of 59, and unrecognized past service costs related to unvested employees of 70.

- The present value of available future refunds and reductions in future contributions is 313.

1. What is the funded status of the company’s pension plan?

2. Calculate the amount of the pension asset that the company will report on its 2010 balance sheet under IFRS if the company chooses to defer unrecognized gains or losses. Is any additional disclosure required?

3. How would the reporting differ under U.S. GAAP?

Solution to 1: The company’s pension plan is overfunded by 513, which is the difference between the defined benefit obligation and the fair value of the plan’s assets (5,485 − 5,998).

Solution to 2: The amount of the defined benefit asset that the company would report on its balance sheet is limited to the lower of two amounts. The first amount is 642, calculated as the net total of the following amounts:

| Present value of defined benefit obligation | 5,485 |

| Fair value of plan assets | (5,998) |

| Unrecognized actuarial losses | (59) |

| Unrecognized past service costs | (70) |

| Total asset | (642) |

Note: When this calculation results in a negative amount, the company will report an asset. When this calculation results in a positive amount, the company will report that amount as a defined benefit liability.

The second amount is calculated as the total of the unrecognized net actuarial losses, past service costs, and the present value of future refunds (or reductions in future contributions to the plan) as follows:

| Unrecognized actuarial losses | 59 |

| Unrecognized past service costs | 70 |

| Present value of future refunds | 313 |

| Total potential reportable asset | 442 |

Because 442 is lower than 642, the company would report a pension asset on its balance sheet of 442. The amount of the asset not reported on the balance sheet (642 − 442 = 200) is disclosed in the notes to the financial statements.

Solution to 3: Under U.S. GAAP, the company would report a pension asset of 513 on its balance sheet, which is the difference between the defined benefit obligation and the plan’s assets (5,485 − 5,998). The amount of the asset under U.S. GAAP differs from the total of the reported and disclosed pension assets (442 reported+200 disclosed = 642) under IFRS because of the different treatment of unrecognized actuarial losses and past service costs.

The IASB and the FASB have identified accounting for postemployment benefits, including pensions, as a project in their collaborative efforts towards convergence. Subsequent changes in accounting standards are expected to address those aspects of current accounting standards that differ.

2.3.2.2. Income Statement: Pension Expense

The periodic cost of a company’s DB pension plan can be thought of as the increase in its pension obligations, offset by earnings on the pension plan’s assets. However, IFRS and U.S. GAAP do not require companies to reflect this entire amount as the pension expense. Pension expense under IFRS and U.S. GAAP is generally composed of five items: current service costs, interest expense accrued on the pension obligation, return on plan assets, past service costs, and actuarial gains or losses. Current and past service costs, interest expense accrued on the pension obligation, and actuarial losses increase the pension expense; return on plan assets and actuarial gains reduce the pension expense. Additionally, some companies report losses on curtailments or settlements as part of the pension expense.8

Items Immediately and Fully Recognized in Pension Expense. Under IFRS and U.S. GAAP, current service costs and interest expense on the pension obligation are fully and immediately reflected as components of a company’s defined benefit pension expense. However, under IFRS, the components of pension expense can be included in various line items including interest expense and, under U.S. GAAP, the components of pension expense are reported within operating expense.

The expected return on the pension plan’s assets, including interest income, dividend income, gains or losses on sales of securities, and unrealized gains and losses (i.e., changes in the value of the assets held by the plan) offsets these costs. Using an expected return decreases volatility in the pension expense, basically smoothing earnings. Standard setters justify using an expected rather than actual return, because pension assets are usually a long-term investment matched to employee retirement. In certain years, actual returns can be more or less than the long-term expected rate of return. To decrease volatility and reflect the long-term nature of the investment, an expected rate of return is used.

In addition to allowing the use of an expected rate of return to smooth earnings, both IFRS and U.S. GAAP include other provisions (sometimes referred to as smoothing mechanisms because they result in a smoother pattern of income). These provisions allow some of the effects of past service costs and of other actuarial gains and losses to be reflected in a company’s DB pension expense over time.

Smoothed Expense Recognition: Past Service Costs. Under IFRS, past service costs (PSC) for vested employees are recognized in the current period when the change to the pension plan is made. For unvested employees, the PSC is amortized over future periods as the employees become vested. Therefore, past service costs are recognized over the vesting period despite the fact that the cost refers to employee service in previous periods. Past service costs are measured as the change in the defined benefit obligation resulting from the plan amendment. Amendments that increase benefits payable also increase pension expense, and those that reduce benefits payable (referred to as negative past service costs) reduce pension expense. Unrecognized past service costs are disclosed in the notes to the financial statements and used to calculate the pension liability or asset that is reported on the balance sheet.

Under U.S. GAAP, past (prior) service costs are reported in other comprehensive income (which in turn increases accumulated other comprehensive income, a component of equity) in the period in which the change occurs. In subsequent periods, these costs are amortized over the average service lives of the affected employees and reported as a component of pension expense. Unamortized past service costs are reported in accumulated other comprehensive income and are not included in the determination of the pension liability or asset.

Smoothed Expense Recognition: Actuarial Gains or Losses. Actuarial gains and losses (AGLs) result from two sources: changes in the actuarial assumptions used in determining the benefit obligation, and differences between the expected and actual returns on pension plan assets. In theory, the differences between expected and actual returns come from short-term fluctuations in market returns; over the long term, expected and actual returns should converge. Therefore, in the long term, actuarial gains and losses arising from differences between the expected and actual returns on plan assets should offset one another.

Under IFRS, companies may recognize actuarial gains and losses immediately either on the income statement or in other comprehensive income, or defer recognition until certain conditions are met under the corridor approach discussed later. If a company chooses to recognize the AGLs in other comprehensive income, they are never reported in income.

Under U.S. GAAP, all actuarial gains and losses are included in the net pension liability or net pension asset and can be reported either in net income or as other comprehensive income. Typically, companies report actuarial gains and losses in other comprehensive income, recognizing the gains or losses in income only when certain conditions are met under the corridor approach discussed later.

Under the IFRS deferred recognition and U.S. GAAP, in the recognition of actuarial gains and losses, companies use either the corridor method or a faster recognition method to determine the minimum amount to be reported on the income statement.

Under the corridor method, the net cumulative unrecognized actuarial gains and losses at the beginning of the reporting period are compared with the defined benefit obligation and the fair value of plan assets at the beginning of the period. If the cumulative amount of unrecognized actuarial gains and losses becomes too large (i.e., exceeds 10 percent of the greater of the defined benefit obligation or the fair value of plan assets), then the excess is amortized over the expected average remaining working lives of the employees participating in the plan and is included as a component of pension expense. The term “corridor” refers to the 10 percent range, and it is only amounts in excess of the corridor that must be amortized.

To illustrate the corridor approach, say the beginning balance of the defined benefit obligation is $5,000,000, the beginning balance of fair value of plan assets is $4,850,000, and the beginning balance of unrecognized actuarial losses is $610,000. The expected average remaining working lives of the plan employees is 10 years. In this scenario, the corridor is $500,000, which is 10 percent of the larger defined benefit obligation. Because the balance of unrecognized actuarial losses exceeds the $500,000 corridor, amortization is required. The amount of the amortization is $11,000, which is the excess of the unrecognized actuarial loss over the corridor divided by the expected average remaining working lives of the plan employees [($610,000 − $500,000) ÷ 10 years].

Actuarial gains or losses can also be amortized more quickly than under the corridor method; companies may use a faster recognition method, provided the company applies the method of amortization to both gains and losses consistently in all periods presented.

Reporting the Pension Expense. IFRS does not require companies to present the various components of pension expense as a net amount (i.e., within a single line item) on the income statement. Instead, companies may disclose portions of net pension expense within different line items on the income statement. For example, companies can record the interest cost and the expected return on plan assets as a part of financing costs on the income statement. U.S. GAAP, however, requires all components of net periodic pension expense (cost) to be aggregated and presented as a net amount within the same line item on the income statement. Both IFRS and U.S. GAAP require total pension expense to be disclosed in the notes to the financial statements.

To summarize, an income statement prepared under IFRS will include current service costs, interest cost, the expected return on plan assets, all past service costs for vested employees and amortized past service costs of unvested employees, the effect of any settlement or curtailment, and perhaps actuarial gains and losses (if the company does not choose to recognize them as other comprehensive income or defer recognizing them).

Under U.S. GAAP, the net periodic pension expense reported on the income statement will include current service costs, interest cost, the expected return on plan assets (or the actual return), the amortization of past service costs, actuarial gains and losses to the extent not reported as other comprehensive income, and the effect of settlement or curtailment gains or losses.9 In summary, the components of a company’s defined benefit pension expense are listed in Exhibit 13-2.

EXHIBIT 13-2 Components of a Company’s Defined Benefit Pension Expense

| Component | Effect on Defined Benefit Pension Expense | Direction of Effect |

| Service costs: Estimated increase in the pension obligation resulting from employees’ service during the period. | Immediately and fully recognized. | Increases the expense. |

| Interest expense on the opening pension obligation. | Immediately and fully recognized. | Increases the expense. |

| Past service costs: Increase in the pension obligation resulting from changes to the terms of a pension plan applicable to employees’ service during previous periods. | IFRS: Vested employees’ portion expensed immediately; unvested employees’ portion expensed over average period until vesting. | Typically increases the expense. |

| U.S. GAAP: Portion not immediately recognized as an expense is shown in other comprehensive income and subsequently amortized over service life of employees. | ||

| Actuarial gains and losses, including changes in a company’s pension obligation arising from changes in actuarial assumptions and differences between the actual and expected returns on plan assets. | IFRS: (1) Recognized immediately either in the income statement or as other comprehensive income (equity); or (2) deferred and amortized using the corridor or a faster recognition method. If the cumulative unrecognized amount of actuarial gains and losses exceeds specified levels, a portion of the excess is recognized as an expense.a U.S. GAAP: Recognized immediately as an expense or deferred and amortized using the corridor or faster recognition method.a All amounts not immediately recognized as an expense are included in other comprehensive income. |

May increase or decrease the expense. |

| Return on plan assets. | Expected return on plan assets is immediately and fully recognized as a reduction of pension expense. Any differences between expected and actual return is considered part of actuarial gains and losses and treated as described previously. |

Decreases the expense.b |

aIf the cumulative amount of unrecognized actuarial gains and losses exceeds 10 percent of the greater of the value of the plan assets or of the present value of the DB obligation (under U.S. GAAP, the projected benefit obligation), the difference must be amortized over the service lives of the employees.

bIf the actual return on plan assets is lower than the expected return on plan assets such that the cumulative difference becomes large enough to require amortization, the amortization of the difference increases pension expense.

2.3.3. More on the Effect of Assumptions and Actuarial Gains and Losses on Pension and Other Postemployment Benefits Expense

As noted, a company’s pension obligation for a DB pension plan is an estimate based on many estimates and assumptions. The amount of future pension payments requires assumptions about employee turnover, length of service, and rate of increase in compensation levels. The length of time the pension payments will be made requires assumptions about employees’ life expectancy post employment. Finally, the present value of these future payments requires assumptions about the appropriate discount rate and the rate at which interest will subsequently accrue on the pension liability.

Changes in any of the assumptions will increase or decrease the pension obligation. An increase in pension obligation resulting from changes in actuarial assumptions is considered an actuarial loss, and a decrease is considered an actuarial gain. The estimate of a company’s pension liability affects several components of annual pension expense, apart from actuarial gains and losses. First, the service cost component of annual pension expense is essentially the amount by which the pension liability increases as a result of the employees’ service during the year. Second, the interest cost component of annual pension expense is based on the amount of the liability. Third, the past service cost component of annual pension expense is the amount by which the pension liability increases because of changes to the plan.

Estimates related to plan assets also affect annual pension expense. Because a company’s pension expense includes the expected return on pension assets rather than the actual return, the assumptions about the expected return on plan assets can have a significant impact. Also, the expected return on plan assets requires estimating in which future period the benefits will be paid. As noted earlier, a divergence of actual returns on pension assets from expected returns results in an actuarial gain or loss.

Understanding the effect of assumptions on the estimated pension obligation and on periodic expenses is important both for interpreting a company’s financial statements and for evaluating whether a company’s assumptions appear relatively conservative or aggressive.

The projected unit credit method is the IFRS approach to measuring the DB obligation. Under the projected unit credit method, each period of service (e.g., year of employment) gives rise to an additional unit of benefit to which the employee is entitled at retirement. In other words, for each period in which an employee provides service, they earn a portion of the postemployment benefits that the company has promised to pay. An equivalent way of thinking about this is that the amount of eventual benefit increases with each additional year of service. The employer measures each unit of service as it is earned, to determine the amount of benefits it is obligated to pay in future reporting periods.

The objective of the projected unit credit method is to allocate the entire expected retirement costs (benefits) for an employee over the employee’s service periods. The defined benefit obligation represents the actuarial present value of all units of benefit (credit) to which the employee is entitled (i.e., has earned) as a result of prior and current periods of service. This obligation is based on actuarial assumptions about demographic variables such as employee turnover and life expectancy, and on estimates of financial variables such as future inflation and the expected long-term return on the plan’s assets. If the pension benefit formula is based on employees’ future compensation levels, then the unit of benefit earned each period will reflect this estimate.

Under both IFRS and U.S. GAAP, the assumed rate of increase in compensation—the expected annual increase in compensation over the employee service period—can have a significant impact on the defined benefit obligation. Another key assumption is the discount rate used to calculate the present value of the future benefits. It represents the rate at which the defined benefit obligation could be effectively settled. This rate is based on current rates of return on high quality corporate bonds with durations consistent with the durations of the benefit.

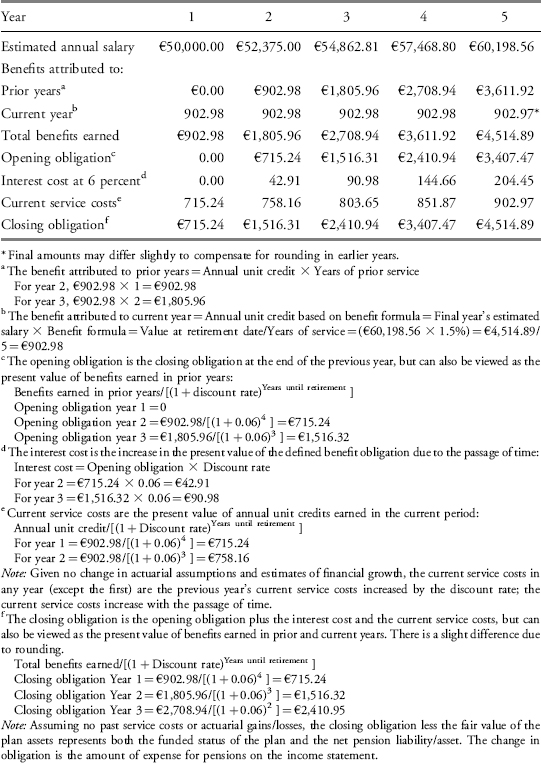

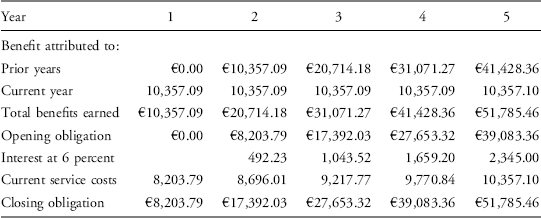

The following example illustrates the calculation of the defined benefit pension obligation and current service costs, using the projected unit credit method, for an individual employee under four different scenarios. The fourth scenario is used to demonstrate the impact on a company’s pension obligation of changes in certain key estimates.

EXAMPLE 13-3 Calculation of Defined Benefit Pension Obligation for an Individual Employee

The following information applies to each of the four scenarios. Assume that a (hypothetical) company establishes a DB pension plan. The employee has a salary in the coming year of €50,000 and is expected to work five more years before retiring. The assumed discount rate is 6 percent and the assumed annual compensation increase is 4.75 percent. For simplicity, assume that there are no changes in actuarial assumptions, all compensation increases are awarded on the first day of the service year, and no additional adjustments are made to reflect the possibility that the employee may leave the company at an earlier date.

| Current salary | €50,000.00 |

| Years until retirement | 5 |

| Annual compensation increases | 4.75% |

| Discount rate | 6.00% |

| Final year’s estimated salarya | €60,198.56 |

aFinal year’s estimated salary = Current year’s salary × [(1+Annual compensation increase)Years until retirement]

At the end of Year 1, final year’s estimated salary = €50,000 × [(1+0.0475)4] = €60,198.56, assuming that the employee’s salary increases by 4.75 percent each year. With no change in assumption about the rate of increase in compensation or date of retirement, the estimate of the final year salary will remain unchanged.

At the end of Year 2, assuming the employee’s salary actually increased by 4.75 percent, final year’s estimated salary = €52,375 × [(1+0.0475)3] = €60,198.56.

Scenario 1: Benefit is paid as a lump sum amount upon retirement

The plan will pay a lump sum pension benefit equal to 1.5 percent of the employee’s final salary for each year of service beyond the date of establishment. The lump sum payment to be paid upon retirement = (Final salary × Benefit formula) × Years of service = (€60,198.56 × 0.015) × 5 = €4,514.89.

![]()

If the discount rate (the interest rate at which the defined benefit obligation could be effectively settled) is assumed to be 0%, the amount of annual unit credit per service year is the amount of the company’s annual obligation, and the closing obligation each year is simply the annual unit credit multiplied by the number of past and current years of service. However, because the assumed discount rate will not equal 0%, the future obligation resulting from current and prior service is discounted to determine the value of the obligation at any point in time.

The following table shows how the obligation builds up for this employee.

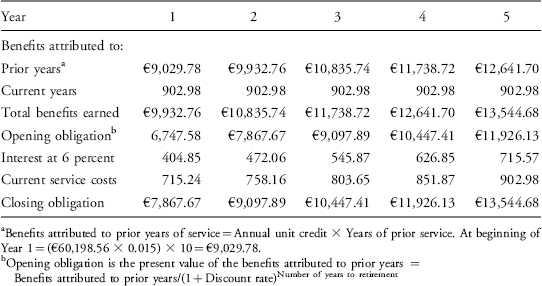

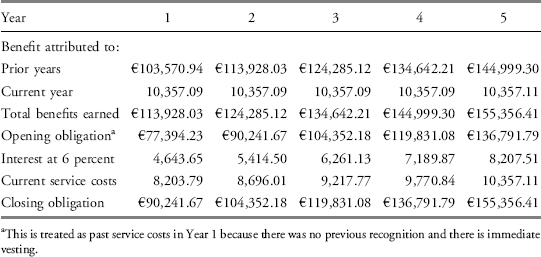

Scenario 2: Prior years of service, and benefit paid as a lump sum upon retirement.

The plan will pay a lump sum pension benefit equal to 1.5 percent of the employee’s final salary for each year of service beyond the date of establishment. In addition, at the time the pension plan is established, the employee is given credit for 10 years of prior service with immediate vesting. The lump sum payment to be paid upon retirement = (Final salary × Benefit formula) × Years of service = (€60,198.56 × 0.015) × 15 = €13,544.68.

![]()

The following table shows how the obligation builds up for this employee.

At beginning of Year 1 = €9,029.78/(1.06)5 = €6,747.58. This is treated as past service costs in Year 1 because there was no previous recognition and there is immediate vesting.

Scenario 3: Employee to receive benefit payments for 20 years (no prior years of service).

Years of receiving pension: 20

Estimated annual payment (end of year) for each of the twenty years = (Estimated final salary × Benefit formula) × Years of service = (€60,198.56 × 0.015) × 5 = €4,514.89.

Value at the end of Year 5 (retirement date) of the estimated future payments = PV of €4,514.89 for 20 years at 6 percent = €51,785.46.10

Annual unit credit = Value at retirement date/Years of service = €51,785.46/5 = €10,357.09.

In this scenario, the pension obligation at the end of Year 3 is €27,653.32 and the pension expense for Year 3 is €10,261.29 (= €1,043.52+€9,217.77).

Scenario 4: Employee to receive benefit payments for 20 years and is given credit for 10 years of prior service with immediate vesting.

Estimated annual payment (end of year) for each of the twenty years = (Estimated final salary × Benefit formula) × Years of service = (€60,198.56 × 0.015) × (10+5) = €13,544.68.

Value at the end of Year 5 (retirement date) of the estimated future payments = PV of €13,544.68 for 20 years at 6 percent = €155,356.41.

Annual unit credit = Value at retirement date/Years of service = €155,356.41/15 = €10,357.09.

EXAMPLE 13-4 The Effect of a Change in Assumptions

Based on Scenario 4 of Example 13-3 (10 years of prior service and the employee receives benefits for 20 years after retirement):

1. What is the effect on the Year 1 closing pension obligation of a 1 percent increase in the assumed discount rate, i.e., from 6 percent to 7 percent? What is the effect on pension expense in Year 1?

2. What is the effect on the Year 1 closing pension obligation of a 1 percent increase in the assumed annual compensation increase, i.e., from 4.75 percent to 5.75 percent? Assume this is independent of the change in Question 1.

Solution to 1: The estimated final salary and the estimated annual payments after retirement are unchanged at €60,198.56 and €13,544.68, respectively. However, the value at the retirement date is changed. Value at the end of Year 5 (retirement date) of the estimated future payments = PV of €13,544.68 for 20 years at 7 percent = €143,492.53. Annual unit credit = Value at retirement date/Years of service = €143,492.53/15 = €9,566.17.

| Year | 1 |

| Benefit attributed to: | |

| Prior years | €95,661.69 |

| Current year | 9,566.17 |

| Total benefits earned | €105,227.86 |

| Opening obligationa | €68,205.46 |

| Interest at 7 percent | 4,774.38 |

| Current service costs | 7,297.99 |

| Closing obligation | €80,277.83 |

aOpening obligation = Benefit attributed to prior years discounted for the remaining time to retirement at the assumed discount rate = 95,661.69/(1+ 0.07)5

A 1 percent increase in the assumed discount rate (from 6 percent to 7 percent) will decrease the Year 1 closing pension obligation by €90,241.67 − €80,277.83 = €9,963.84. The Year 1 pension expense declined from €12,847.44 (= 4,643.65+ 8,203.79) to €12,072.37 (= 4,774.38+7,297.99). The change in the interest component is a function of the decline in the opening obligation (which will decrease the interest component) and the increased discount rate (which will increase the interest component). In this case, the increase in the discount rate dominated and the interest component increased. The current service costs and the opening obligation both declined because of the increase in the discount rate.

Solution to 2: The estimated final salary is [€50,000 × [(1+0.0575)4] = €62,530.44. Estimated annual payment for each of the twenty years = (Estimated final salary × Benefit formula) × Years of service = (€62,530.44 × 0.015) × (10+5) = €14,069.35. Value at the end of Year 5 (retirement date) of the estimated future payments = PV of €14,069.35 for 20 years at 6 percent = €161,374.33. Annual unit credit = Value at retirement date/Years of service = €161,374.33/15 = €10,758.29.

| Year | 1 |

| Benefit attributed to: | |

| Prior years | €107,582.89 |

| Current year | 10,758.29 |

| Total benefits earned | €118,341.18 |

| Opening obligation | €80,392.19 |

| Interest at 6 percent | 4,823.53 |

| Current service costs | 8,521.57 |

| Closing obligation | €93,737.29 |

A 1 percent increase in the assumed annual compensation increase (from 4.75 percent to 5.75 percent) will increase the pension obligation by €93,737.29 − €90,241.67 = €3,495.62.

Example 13-4 illustrates that an increase in the assumed discount rate will decrease a company’s pension obligation. In the Solution to 1, there is a slight increase in the interest component of the pension obligation and pension expense. However, the interest component of the pension obligation and pension expense (calculated as the discount rate times the obligation at the beginning of the year) may decrease because the decrease in the opening obligation may more than offset the effect of the increase in the discount rate; an exception occurs when the pension obligation is of a short duration; i.e., time to retirement is short.

Example 13-4 also illustrates that an increase in the assumed rate of annual compensation increase will increase a company’s pension obligation when the pension formula is based on final year’s salary. In addition, a higher assumed rate of annual compensation increase will increase the service components and the interest component of a company’s periodic pension expense because of an increased annual unit credit and the resulting increased obligation. An increase in life expectancy also will increase the pension obligation unless the promised pension payments are independent of life expectancy; e.g., paid as a lump sum or over a fixed period.

Finally, because the expected return on plan assets reduces pension expense, a higher expected return will decrease pension expense. Exhibit 13-3 summarizes the impact of some key estimates on the balance sheet and the periodic benefit-related expense.

EXHIBIT 13-3 Impact of Key DB Pension Assumptions on Balance Sheet and Periodic Expense

| Assumption | Impact of Assumption on Balance Sheet | Impact of Assumption on Periodic Expense |

| Higher discount rate. | Lower obligation. | Pension expense will typically be lower because of lower opening obligation and lower service costs. |

| Higher rate of compensation increase. | Higher obligation. | Higher service costs. |

| Higher expected return on plan assets. | No effect, because fair value of plan assets are used on balance sheet | Lower pension expense. |

Accounting for other postemployment benefits also requires assumptions and estimates. For example, assumed trends in health care costs are an important component of estimating costs of postemployment health care plans. A higher assumed medical expense inflation rate will result in a higher postemployment medical obligation. Companies also estimate various patterns of health care cost trend rates—for example, higher in the near term, but becoming lower after some point in time. For postemployment health plans, an increase in the assumed inflationary trends in health care costs or an increase in life expectancy will increase the obligation and associated periodic expense of these plans.

The previous sections have explained how the amounts to be reported on the balance sheet are calculated, how the pension expense on the income statement reflects the five components, and how changes in assumptions can affect pension-related amounts. The next section evaluates disclosures of pension and other postemployment benefits, including disclosures about key assumptions.

2.4. Disclosures of Pension and Other Postemployment Benefits

Several aspects of the accounting for pensions and other postemployment benefits described earlier can affect comparative financial analysis using ratios based on financial statements.

- Differences in key assumptions can affect comparisons across companies.

- Differences between IFRS and U.S. GAAP in how the reported net pension liability (or net pension asset) and pension expense are determined can affect comparisons.

- The smoothing mechanisms within the accounting standards can obscure the underlying economic expense.

- Under U.S. GAAP, all of the components of pension expense are reported in operating expense on the income statement, even though some of the components are of a financial nature (specifically, interest expense and the expected return on assets). However, under IFRS the components of pension expense can be included in various line items.

- Cash flow information may not be comparable. Under IFRS, some portion of the amount of contributions might be treated as a financing activity rather than an operating activity and under U.S. GAAP, the contribution is treated as an operating activity.

Information related to pensions can be obtained from various portions of the financial statement note disclosures and appropriate analytical adjustments can be made. In the following sections, we examine pension plan note disclosures to address analytical issues.

2.4.1. Assumptions

Companies disclose their assumptions about discount rates, expected compensation increases, medical expense inflation, and expected return on plan assets. Comparing these assumptions over time and across companies provides a basis to assess any conservative or aggressive biases. Some companies also disclose the effects of a change in their assumptions.

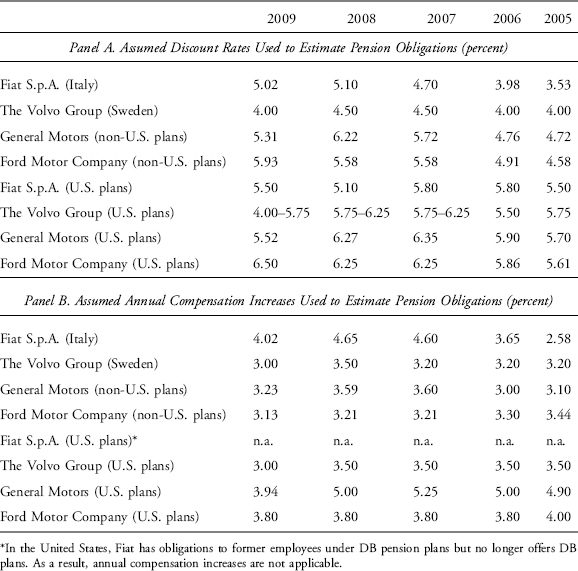

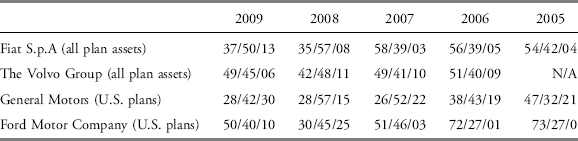

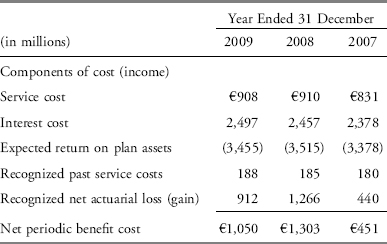

Exhibit 13-4 presents the assumed discount rates (Panel A) and assumed annual compensation increases (Panel B) to estimate pension obligations for four companies operating in the automotive and equipment manufacturing sector. Fiat S.p.A. (an Italian-based company) and The Volvo Group11 (a Swedish-based company) use IFRS. General Motors and Ford Motor Company are U.S.-based companies that use U.S. GAAP. All of these companies have both U.S. and non-U.S. defined benefit pension plans, which facilitates comparison.

The assumed discount rates used to estimate pension obligations are generally based on the market interest rates of high quality corporate fixed income investments with a maturity profile similar to the timing of a company’s future pension payments. The trend in discount rates across the companies (in both their non-U.S. plans and U.S. plans) is generally similar. In the non-U.S. plans, discount rates increased from 2005 to 2008 and then decreased in 2009 except for Fiat, which increased its discount rate in 2009. In the U.S. plans, discount rates increased from 2005 to 2007 and held steady or decreased in 2008. In 2009, Fiat and Ford’s discount rates increased while Volvo and GM’s discount rates decreased. Ford had the highest assumed discount rates for both its non-U.S. and U.S. plans in 2009. Recall that a higher discount rate assumption results in a lower estimated pension obligation. Therefore, the use of a higher discount rate compared to its peers may indicate a less conservative bias.

Explanations for differences in the level of the assumed discount rates, apart from bias, are differences in the regions/countries involved and differences in the timing of obligations (for example, differences in the percentage of employees covered by the DB pension plan that are at or near retirement). In this example, difference in regions/countries might explain the difference in rates used for the non-U.S. plans, but would not explain the difference in the rates shown for the companies’ U.S. plans. The timing of obligations under the companies’ DB pension plans likely varies, so the relevant market interest rates selected as the discount rate will vary accordingly. Because the timing of the pension obligations is not disclosed, differences in timing cannot be ruled out as an explanation for differences in discount rates.

An important consideration is whether the assumptions are internally consistent. For example, do the company’s assumed discount rates and assumed compensation increases reflect a consistent view of inflation? For Volvo, both the assumed discount rates and the assumed annual compensation increases (for both its non-U.S. and U.S. plans) are lower than those of the other companies, so the assumptions appear internally consistent. The assumptions are consistent with plans located in lower inflation regions. Recall that a lower rate of compensation increase results in a lower estimated pension obligation.

In Ford’s U.S. and non-U.S. pension plans, the assumed discount rate is increasing and the assumed rate of compensation increase is decreasing or holding steady in 2009. Each of these will reduce the pension obligation. Therefore, holding all else equal, Ford’s pension liability is decreasing because of the higher assumed discount rate and the reduced assumed rate of compensation increase.

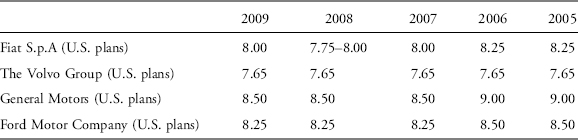

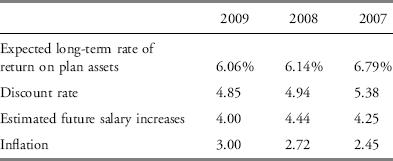

Exhibit 13-5 presents a comparison of the four companies’ assumptions about the expected return on U.S. pension plan assets. Recall that a higher expected return on plan assets lowers the periodic pension expense. (Of course, a higher expected return on plan assets presumably reflects more risky investments, so it would not be advisable for a company to simply invest in riskier investments to reduce periodic pension expense.) Analysts should compare the company’s assumptions in the context of its chosen asset allocation.

EXHIBIT 13-5 Assumed Expected Return on U.S. Plan Pension Expense (percent)

EXHIBIT 13-6 Allocation of Plan Assets (Equity/Debt/Other; in percent)

Although the disclosures for Fiat and Volvo do not separately reveal plan assets for the U.S. plans, comparison of the overall asset allocations (Exhibit 13-6) yields some insights. From Exhibit 13-5, General Motors assumes the highest expected return and Volvo assumes the lowest expected returns. A higher expected return is consistent with a greater portion of plan assets being allocated to riskier investments such as equities. However, this does not seem to be the case as Volvo’s 49 percent allocation to equity is actually higher than two of its peers (Fiat and General Motors) and very close to the other (Ford). However, GM has much higher allocation to “Other” and these assets might be expected to earn a high return. Recall that a higher expected return on plan assets lowers a company’s pension expense.

2.4.1.1. Assumptions: Other Postemployment Benefits

Companies with other postemployment benefits disclose information about these benefits, including assumptions made to estimate the obligation and expense. For example, postemployment health care plans, a type of defined benefit plan, disclose assumptions about increases in health care costs. The assumptions are typically that the inflation rate in health care costs will taper off to some lower, constant rate at some year in the future. That future inflation rate is known as the ultimate health care trend rate. Holding all else equal, each of the following assumptions would result in a higher benefit obligation and a higher periodic expense:

- A higher assumed near-term increase in health care costs.

- A higher assumed ultimate health care trend rate.

- A later year in which the ultimate health care trend rate is assumed to be reached.

Conversely, holding all else equal, each of the following assumptions would result in a lower benefit obligation and a lower periodic expense:

- A lower assumed near-term increase in health care costs.

- A lower assumed ultimate health care trend rate.

- An earlier year in which the ultimate health care trend rate is assumed to be reached.

Example 13-5 examines two companies’ assumptions about trends in U.S. health care costs.

EXAMPLE 13-5 Comparison of Assumptions about Trends in U.S. Health Care Costs

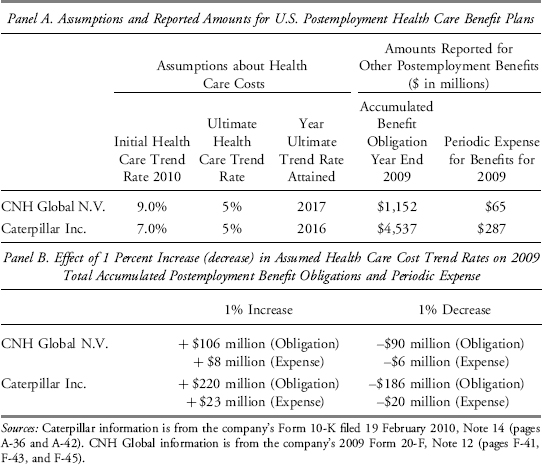

In addition to disclosing assumptions about health care costs, companies also disclose information on the sensitivity of the measurements of both the obligation and periodic expense to changes in those assumptions. Exhibit 13-7 presents information obtained from the notes to the financial statements for CNH Global N.V. (a Dutch manufacturer of construction and mining equipment) and Caterpillar Inc. (a U.S. manufacturer of construction and mining equipment, engines, and turbines). Each company has U.S. employees for whom they provide postemployment health care benefits.

Panel A shows the companies’ assumptions about health care costs and the amounts each reported for postemployment health care benefit plans. For example, CNH assumes that the initial year’s (2010) increase in health care costs will be 9 percent, and this rate of increase will decline to 5 percent over the next 7 years to 2017. Caterpillar assumes a lower initial year increase of 7 percent and a decline to the ultimate health care trend rate of 5 percent in 2016.

Panel B shows the effect of a 1 percent increase or decrease in the assumed health care cost trend rates. A 1 percentage point increase in the assumed health care cost trend rates would increase Caterpillar’s 2009 service and interest cost component of the other postemployment benefit costs by $23 million and the related obligation by $220 million. A 1 percentage point increase in the assumed health care cost trend rates would increase CNH Global’s 2009 service and interest cost component of the other postemployment benefit costs by $8 million and the related obligation by $106 million.

EXHIBIT 13-7 Postemployment Health Care Plan Disclosures

Based on the information in Exhibit 13-7, answer the following questions.

1. Which company’s assumptions about health care costs appear less conservative?

2. What would be the effect of adjusting the postemployment benefit obligation and the periodic postemployment benefit expense of the less conservative company for a 1 percent increase in health care cost trend rates? Does this make the two companies more comparable?

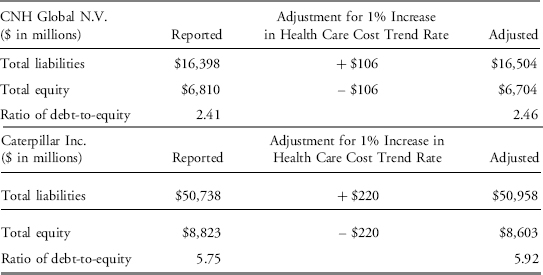

3. What would be the change in each company’s 2009 ratio of debt-to-equity assuming a 1 percent increase in the health care cost trend rate? Assume the change would have no impact on taxes. Total liabilities and total equity at 31 December 2009 are given here.

| At 31 December 2009 (in millions of U.S. dollars) | CNH Global N.V. | Caterpillar Inc. |

| Total liabilities | $16,398 | $50,738 |

| Total equity | $6,810 | $8,823 |

Solution to 1: Caterpillar’s assumptions about health care costs appear less conservative (the assumptions will result in lower health care costs) than CNH’s. Caterpillar’s initial assumed health care cost increase of 7 percent is significantly lower than CNH’s assumed 9 percent. Further, Caterpillar assumes that the ultimate health care cost trend rate of 5 percent will be reached a year earlier than assumed by CNH.

Solution to 2: The sensitivity disclosures indicate that a 1 percent increase in the assumed health care cost trend rate would increase Caterpillar’s postemployment benefit obligation by $220 million and its periodic cost by $23 million. However, Caterpillar’s initial health care cost trend rate is 2 percent lower than CNH’s. Therefore, the impact of a 1 percent change for Caterpillar multiplied by 2 provides an approximation of the adjustment required for comparability to CNH. Note, however, that the sensitivity of the pension obligation and expense to a change of more than 1 percent in the assumed health care cost trend rate cannot be assumed to be exactly linear, so this adjustment is only an approximation. Further, there may be justifiable differences in the assumptions based on the location of their U.S. operations.

Solution to 3: A 1 percent increase in the health care cost trend rate increases CNH’s ratio of debt-to-equity by about 2 percent from 2.41 to 2.46. A 1 percent increase in the health care cost trend rate increases Caterpillar’s ratio of debt-to-equity by about 3 percent from 5.75 to 5.92.

This section has explored the use of pension and other postemployment benefits disclosures to assess a company’s assumptions and explore how the assumptions can affect comparisons across companies. The following sections describe the use of disclosures to analyze the underlying economics of a company’s pension and other postemployment benefits.

2.4.2. Underlying Economic Pension Liability (or Asset)

Because the accounting and reporting of DB pension plans differ between IFRS and U.S. GAAP and companies have different options under IFRS, it is useful to be able to assess a company’s underlying pension liability (or asset) as the pension obligation less plan assets (funded position or funded status). U.S. GAAP reports this net amount on the balance sheet, so additional adjustments are not needed to reflect the underlying economics. IFRS requires additional adjustments to reflect the underlying economic liability (or asset) if a company defers AGLs and/or does not report the obligation for all past service costs. In addition, IFRS includes a limitation on the amount of a pension asset that can be reported. Thus, the amount reported under IFRS is not necessarily equivalent to the economic perspective of the net funded position. Analysts look at the notes to the financial statements to find the gross benefit obligation and the fair value of the assets allocated to pay the obligation to determine the economic net funded position.

Another consideration is that under both standards, the amount appearing in the balance sheet is a net amount. Analysts can use information from the notes to adjust a company’s assets and liabilities for the gross amount of the benefit plan assets and the gross amount of the benefit plan liabilities. An argument for making such adjustments is that they reflect the underlying economic liabilities and assets of a company; however, it should be recognized that actual consolidation is precluded by laws protecting a pension or other benefit plan as a separate legal entity.

At a minimum, an analyst will compare the gross benefit obligation (i.e., the benefit obligation without deducting related plan assets) to the sponsoring company’s total assets including the gross amount of the benefit plan assets, shareholders’ equity, and earnings. Although presumably infrequent in practice, if the gross benefit obligation is large relative to these items, a small change in the pension liability can have a significant financial impact on the sponsoring company.

EXAMPLE 13-6 Summary of Underlying Economic Liability (or Asset)

The following information is from the 2009 Annual Report of Akzo Nobel AG, which reports under IFRS (€ in millions).

| From Balance Sheet | 2008 | 2009 |

| Total liabilities | 10,821 | 10,635 |

| Total equity | 7,913 | 8,245 |

Note 1: Summary of Significant Accounting Policies (excerpt)

Actuarial gains and losses that arise in calculating our obligation in respect of a plan, are recognized to the extent that any cumulative unrecognized actuarial gains or losses exceed 10 percent of the greater of the present value of the defined benefit obligation and the fair value of plan assets. That portion of the actuarial gains and losses is recognized in the statement of income over the expected average remaining working lives of the employees participating in the plan. When the benefits of a plan are improved, the portion of the increased benefit relating to past service by employees is recognized as an expense in the statement of income on a straight-line basis over the average period until the benefits become vested. To the extent that the benefits vest immediately, the expense is recognized immediately in the statement of income.

Note 17: Provisions (excerpt)

| 2008 | 2009 | |

| Defined benefit obligation at year-end | −11,468 | −13,688 |

| Plan assets at year-end | 10,480 | 11,821 |

| Funded Status | −988 | −1,867 |

| Unrecognized net loss (gain) | 35 | 1,065 |

| Unrecognized past service costs | 0 | 4 |

| Restriction on asset recognition | −34 | 0 |

| Net balance pension provisions | −987 | −798 |

In Note 17, the company indicates the underfunded status with a negative sign so unrecognized net (actuarial) loss and past service costs are added rather than subtracted as shown in Section 2.3.2.1.

1. What is the net pension liability or asset reported by Akzo Nobel at 31 December 2008 and 2009?

2. What is the funded status of the company’s defined benefit plan?

3. What would be the changes in the company’s 2008 and 2009 ratio of debt-to-equity assuming it reported all pension obligations and assets (the funded status of the plan) on the balance sheet? Comment on the changes.

Solution to 1: From the note disclosure on pensions, Akzo Nobel reports a net pension liability of €987 million and €798 million at 31 December 2008, and 2009, respectively. The note disclosures on accounting policies indicate that the company has chosen to defer recognition of actuarial gains or losses under IFRS. The note also discloses that, in accordance with IFRS, past service costs for unvested employees will be recognized over the vesting period.

Solution to 2: Akzo Nobel’s defined benefit plan was underfunded by €988 million and €1,867 million at 31 December 2008 and 2009, respectively. In other words, the pension obligations exceeded the plan assets in both years.

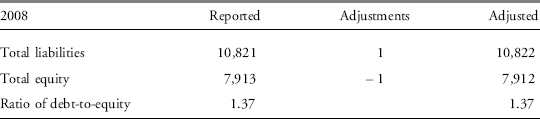

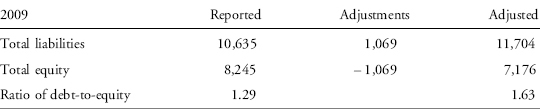

Solution to 3: If Akzo Nobel reported the funded status of its pensions on the balance sheet, its pension liability would increase by €1 million in 2008 (funded status of −988 minus balance sheet liability of −987). The company’s pension liability would increase by €1,069 million in 2009 (funded status of −1,867 minus balance sheet liability of −798).

The difference between the plan’s funded status and the liability arise because of the unrecognized amounts, shown in the following table:

| Difference between Funded Status and Reported Liability | 2008 | 2009 |

| Unrecognized net loss (gain) | 35 | 1,065 |

| Unrecognized past service costs | 0 | 4 |

| Restriction on asset recognition | −34 | 0 |

| Net Difference | 1 | 1,069 |

In both 2008 and 2009, the net unrecognized amounts increase the company’s pension liability. Its unrecognized amounts in 2008 are small, €1 million, so there is no effect on the ratio of debt-to-equity. Its unrecognized amounts in 2009 are larger, at €1,069 million, and have a greater effect on the ratio of debt-to-equity. With the adjustment, the ratio of debt-to-equity in 2009 increases from 1.29 to 1.63 or about 26 percent. Interestingly, the reported ratio of debt-to-equity is lower in 2009 than in 2008. With the adjustment for pensions, it becomes higher in 2009 than in 2008.

2.4.3. Underlying Economic Expense (or Income)

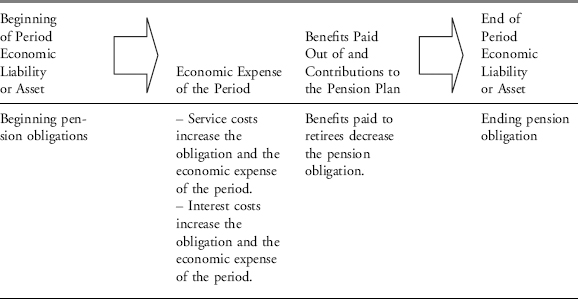

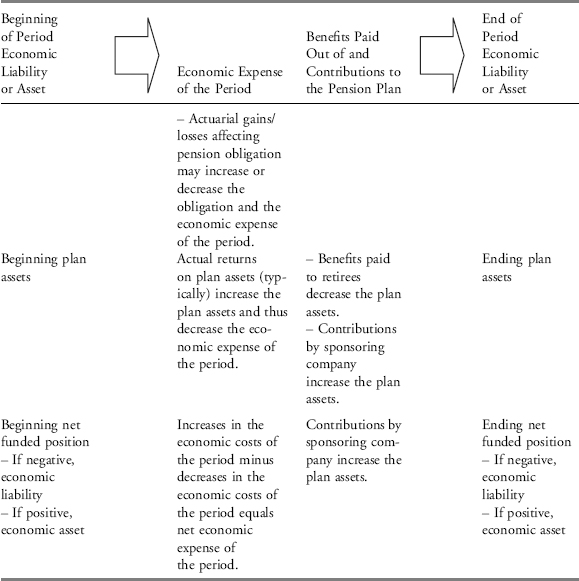

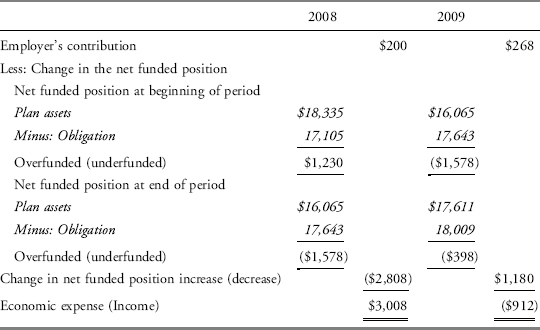

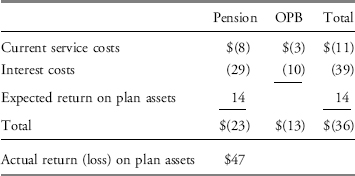

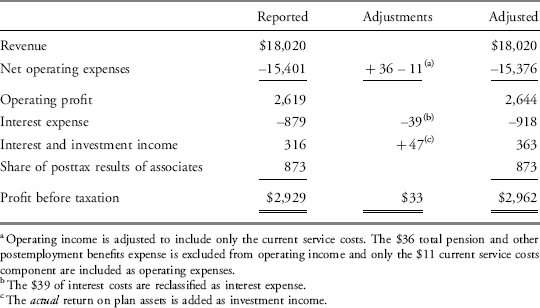

As illustrated in Exhibit 13-8, the two main reasons for changes in the economic net funded status of a DB pension plan are the economic periodic costs (as opposed to reported periodic costs) of the pension plan, and contributions to the plan by the sponsoring company. Benefits paid to retirees decrease the pension obligations and the plan assets by an identical amount and thus have no impact on the net funded status. The economic periodic costs of a company’s DB pension plan comprise net increases in pension obligations (excluding the impact of benefits paid) offset by earnings on pension plan assets. The economic periodic costs of a company’s DB pension plan can be calculated in either of the following ways: by summing each item (other than benefits paid) that increases or decreases the pension obligation and deducting actual returns on pension plan assets; or equivalently, by taking the contributions made by the sponsoring company and adjusting for the change in the plan’s net funded status over the period. Because the computations yield equivalent results, analysts can use the approach they consider most intuitive to determine the economic pension expense.

EXHIBIT 13-8 Summary of Underlying Economic Liability (or Asset) and Economic Expense of the Period

Example 13-7 illustrates the estimation of economic pension expense for the J.M. Smucker Company (NYSE: SJM), which prepares its financial statements in accordance with U.S. GAAP. The estimation of pension expense is shown first for U.S. GAAP because the reported and economic net funded positions are equivalent; this allows the use of the format of Exhibit 13-8 to estimate the economic pension expense.

EXAMPLE 13-7 Summary of Underlying Economic Expense

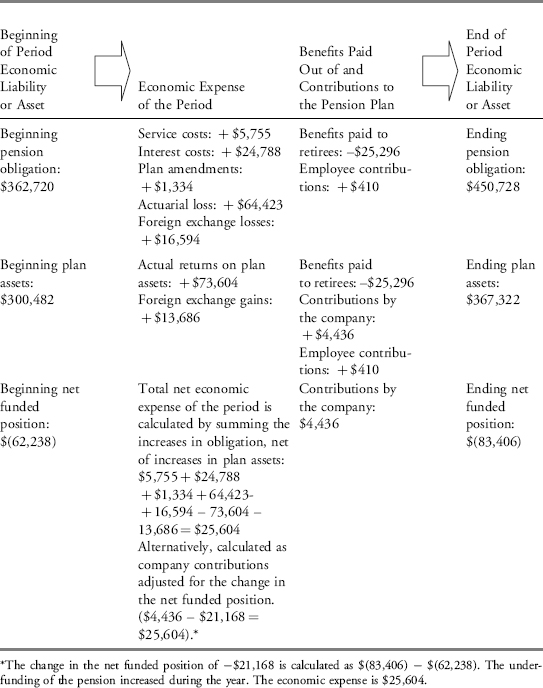

The following information is from Note G of the 2010 Annual Report of J.M. Smucker Company (in $ thousands) for the year ended 30 April 2010.

- Beginning pension obligation was $362,720, and beginning plan assets were $300,482.

- Service costs of $5,755 and interest costs of $24,788 increased Smucker’s pension obligation.

- Plan amendments of $1,334 increased Smucker’s pension obligation.

- Actuarial losses recognized of $64,423 increased Smucker’s pension obligation.

- Benefits paid to retired employees of $25,296 decreased Smucker’s pension obligation and also the pension assets.

- Foreign exchange losses of $16,594 increased Smucker’s pension obligation.

- Actual returns on the plan assets totaled $73,604.

- Foreign exchange gains and other adjustment totaling $13,686 increased Smucker’s plan assets.

- Smucker contributed $4,436 to the plan. Employees contributed $410.

- Reported net periodic benefit cost was $15,302, which includes service costs of $5,755, interest costs of $24,788, amortization of prior service costs of $1,362, amortization of net actuarial loss of $6,291, and expected return on plan assets of 22,894. ($5,755+$24,788+$1,362 +$6,291 − $22,894 = $15,302).

1. Using the Exhibit 13-8 format, determine the economic expense related to pensions during the year ended 30 April 2010.

2. Determine the effect on Smucker’s net income assuming Smucker’s had reported the economic expense related to pensions. Smucker’s net income for the year ended 30 April 2010 was $494,138 and its effective tax rate was 32.4 percent.

Solution to 1:

Based on this information, the economic expense of the period equals $25,604 compared with the reported periodic pension cost of $15,302. This is primarily due to the smoothing mechanisms permitted under accounting standards. Specifically, the expected returns on plan assets of $22,894 differed from actual returns of $73,604, and an amortization expense for previous actuarial losses of $6,291 differed from the period’s actuarial gain of $64,423. Plan amendments increased the economic expense by $1,344, similar to the amount of prior service costs amortized of $1,362. The final difference is the net foreign exchange impact of $2,908.

Solution to 2: Based on the Solution to 1, the pension expense would increase by $10,302 (economic expense of the period $25,604 less the reported periodic pension cost of $15,302). Adjusting for taxes, net income would decrease by $6,964 [ = $10,302 × (1−0.324)] to $487,174, a decline of about 1.5 percent.

As illustrated, the pension expense shown on a company’s income statement does not reflect the economic expense of the period primarily because, under certain conditions, accounting standards permit several components of pension expense to be smoothed into income over time. The components of the cost that may be smoothed include past service costs and actuarial gains and losses. Recall that actuarial gains and losses result from two sources: changes in the actuarial assumptions used to determine the benefit obligation, and differences between the expected and actual returns on pension plan assets. Analysts can adjust for these items and determine the underlying economic expense (or income).

The economic pension expense of the period effectively includes the following: actual returns on plan assets, all actuarial gains and losses arising in the period, and all service costs arising in the period (whether they relate to current service or past service). Further, the economic pension expense of the period effectively excludes any amortization of past service costs, any amortization of net actuarial gains and losses, and the amount of expected returns on plan assets.

Example 13-8 illustrates the estimation of economic pension expense for Novartis Group [NYSE (ADR): NVS], which prepares its financial statements in accordance with IFRS.

EXAMPLE 13-8 Adjusting Pension and Other Postemployment Benefits Expense to Underlying Economic Expense or Income

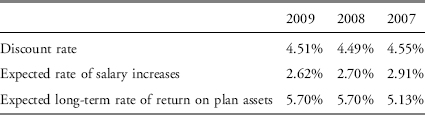

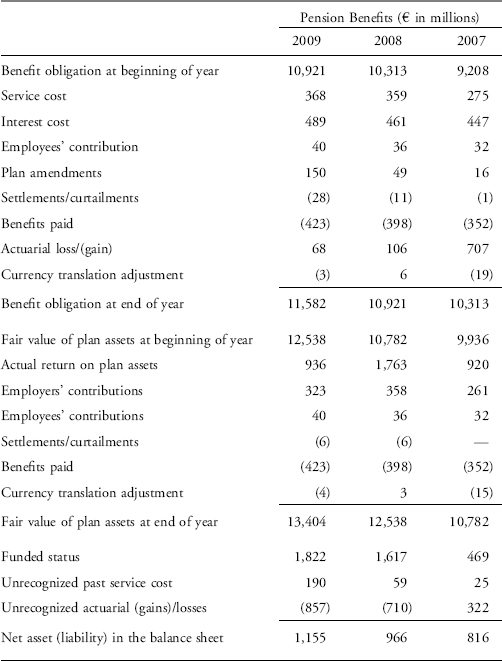

Use the following postemployment benefit information reported by Novartis Group (Novartis Group Annual Report, 2009) to answer the following questions for fiscal 2008 and 2009. All amounts are in millions.