CHAPTER 7

FINANCIAL ANALYSIS TECHNIQUES

After completing this chapter, you will be able to do the following:

- Describe tools and techniques used in financial analysis, including their uses and limitations.

- Classify, calculate, and interpret activity, liquidity, solvency, profitability, and valuation ratios.

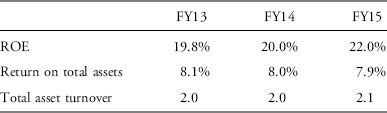

- Describe the relationships among ratios and evaluate a company using ratio analysis.

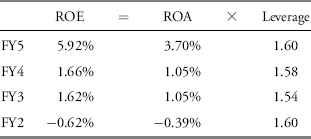

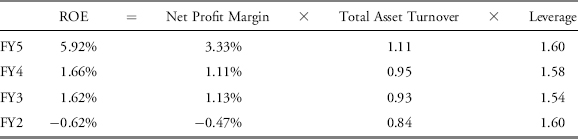

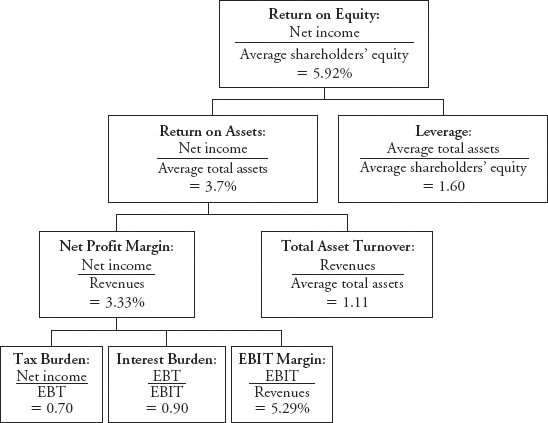

- Demonstrate the application of DuPont analysis of return on equity, and calculate and interpret the effects of changes in its components.

- Calculate and interpret ratios used in equity analysis, credit analysis, and segment analysis.

- Describe how ratio analysis and other techniques can be used to model and forecast earnings.

Financial analysis tools can be useful in assessing a company’s performance and trends in that performance. In essence, an analyst converts data into financial metrics that assist in decision making. Analysts seek to answer such questions as: How successfully has the company performed, relative to its own past performance and relative to its competitors? How is the company likely to perform in the future? Based on expectations about future performance, what is the value of this company or the securities it issues?

A primary source of data is a company’s annual report, including the financial statements and notes, and management commentary (operating and financial review or management’s discussion and analysis). This chapter focuses on data presented in financial reports prepared under International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) and United States generally accepted accounting principles (U.S. GAAP). However, financial reports do not contain all the information needed to perform effective financial analysis. Although financial statements do contain data about the past performance of a company (its income and cash flows) as well as its current financial condition (assets, liabilities, and owners’ equity), such statements do not necessarily provide all the information useful for analysis nor do they forecast future results. The financial analyst must be capable of using financial statements in conjunction with other information to make projections and reach valid conclusions. Accordingly, an analyst typically needs to supplement the information found in a company’s financial reports with other information, including information on the economy, industry, comparable companies, and the company itself.

This chapter describes various techniques used to analyze a company’s financial statements. Financial analysis of a company may be performed for a variety of reasons, such as valuing equity securities, assessing credit risk, conducting due diligence related to an acquisition, or assessing a subsidiary’s performance. This chapter will describe techniques common to any financial analysis and then discuss more specific aspects for the two most common categories: equity analysis and credit analysis.

Equity analysis incorporates an owner’s perspective, either for valuation or performance evaluation. Credit analysis incorporates a creditor’s (such as a banker or bondholder) perspective. In either case, there is a need to gather and analyze information to make a decision (ownership or credit); the focus of analysis varies because of the differing interest of owners and creditors. Both equity and credit analyses assess the entity’s ability to generate and grow earnings, and cash flow, as well as any associated risks. Equity analysis usually places a greater emphasis on growth, whereas credit analysis usually places a greater emphasis on risks. The difference in emphasis reflects the different fundamentals of these types of investments: The value of a company’s equity generally increases as the company’s earnings and cash flow increase, whereas the value of a company’s debt has an upper limit.1

The balance of this chapter is organized as follows: Section 2 recaps the framework for financial statements and the place of financial analysis techniques within the framework. Section 3 provides a description of analytical tools and techniques. Section 4 explains how to compute, analyze, and interpret common financial ratios. Sections 5 through 8 explain the use of ratios and other analytical data in equity analysis, credit analysis, segment analysis, and forecasting, respectively. Section 9 summarizes the key points of the chapter, and practice problems in the CFA Institute multiple-choice format conclude the chapter.

2. THE FINANCIAL ANALYSIS PROCESS

In financial analysis, it is essential to clearly identify and understand the final objective and the steps required to reach that objective. In addition, the analyst needs to know where to find relevant data, how to process and analyze the data (in other words, know the typical questions to address when interpreting data), and how to communicate the analysis and conclusions.

2.1. The Objectives of the Financial Analysis Process

Because of the variety of reasons for performing financial analysis, the numerous available techniques, and the often-substantial amount of data, it is important that the analytical approach be tailored to the specific situation. Prior to beginning any financial analysis, the analyst should clarify the purpose and context, and clearly understand the following:

- What is the purpose of the analysis? What questions will this analysis answer?

- What level of detail will be needed to accomplish this purpose?

- What data are available for the analysis?

- What are the factors or relationships that will influence the analysis?

- What are the analytical limitations, and will these limitations potentially impair the analysis?

Having clarified the purpose and context of the analysis, the analyst can select the set of techniques (e.g., ratios) that will best assist in making a decision. Although there is no single approach to structuring the analysis process, a general framework is set forth in Exhibit 7-1.2 The steps in this process were discussed in more detail in an earlier chapter; the primary focus of this chapter is on Phases 3 and 4, processing and analyzing data.

EXHIBIT 7-1 A Financial Statement Analysis Framework

| Phase | Sources of Information | Output |

| 1. Articulate the purpose and context of the analysis |

|

|

| 2. Collect input data |

|

|

| 3. Process data |

|

|

| 4. Analyze/interpret the processed data |

|

|

| 5. Develop and communicate conclusions and recommendations (e.g., with an analysis report) |

|

|

| 6. Follow up |

|

|

2.2. Distinguishing between Computations and Analysis

An effective analysis encompasses both computations and interpretations. A well-reasoned analysis differs from a mere compilation of various pieces of information, computations, tables, and graphs by integrating the data collected into a cohesive whole. Analysis of past performance, for example, should address not only what happened but also why it happened and whether it advanced the company’s strategy. Some of the key questions to address include:

- What aspects of performance are critical for this company to successfully compete in this industry?

- How well did the company’s performance meet these critical aspects? (Established through computation and comparison with appropriate benchmarks, such as the company’s own historical performance or competitors’ performance.)

- What were the key causes of this performance, and how does this performance reflect the company’s strategy? (Established through analysis.)

If the analysis is forward looking, additional questions include:

- What is the likely impact of an event or trend? (Established through interpretation of analysis.)

- What is the likely response of management to this trend? (Established through evaluation of quality of management and corporate governance.)

- What is the likely impact of trends in the company, industry, and economy on future cash flows? (Established through assessment of corporate strategy and through forecasts.)

- What are the recommendations of the analyst? (Established through interpretation and forecasting of results of analysis.)

- What risks should be highlighted? (Established by an evaluation of major uncertainties in the forecast and in the environment within which the company operates.)

Example 7-1 demonstrates how a company’s financial data can be analyzed in the context of its business strategy and changes in that strategy. An analyst must be able to understand the “why” behind the numbers and ratios, not just what the numbers and ratios are.

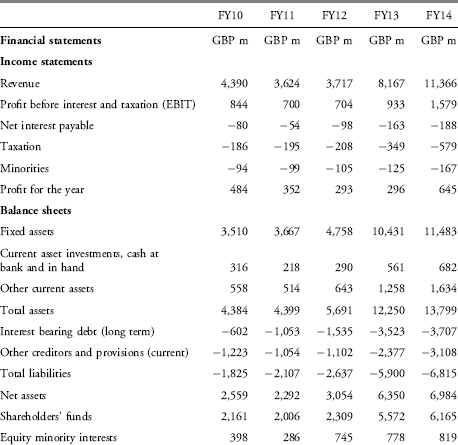

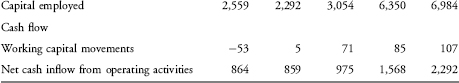

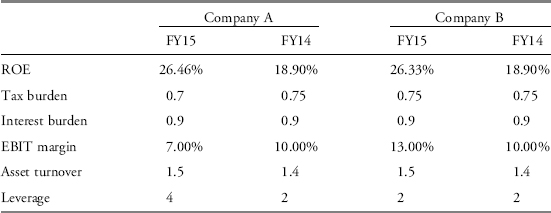

EXAMPLE 7-1 Strategy Reflected in Financial Performance

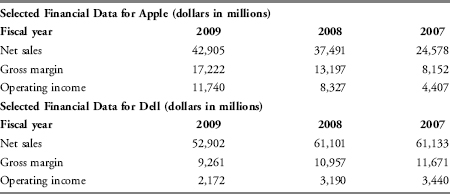

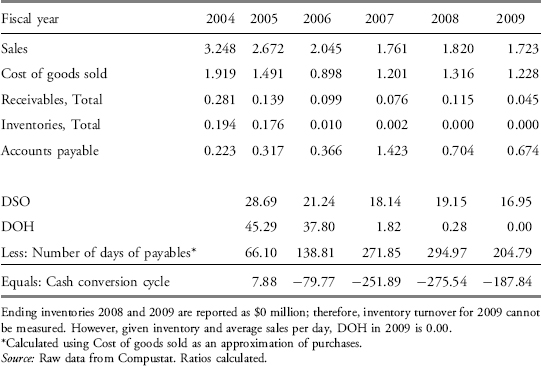

Apple Inc. (NasdaqGS: AAPL) and Dell Inc. (NasdaqGS: DELL) engage in the design, manufacture, and sale of computer hardware and related products and services. Selected financial data for 2007 through 2009 for these two competitors follow here. Apple’s fiscal year (FY) ends on the final Saturday in September (for example, FY2009 ended on 26 September 2009). Dell’s fiscal year ends on the Friday nearest 31 January (for example, FY2009 ended on 29 January 2010 and FY2007 ended on 1 February 2008).

Source: Apple’s Forms 10-K and 10-K/A and Dell’s Form 10-K.

Apple reported a 53 percent increase in net sales from FY2007 to FY2008 and a further increase in FY2009 of approximately 14 percent. Gross margin increased 62 percent from FY2007 to FY2008 and increased 30 percent from FY2008 to FY2009. From FY2007 to FY2009, the gross margin more than doubled. Also, the company’s operating income almost tripled over the three-year period. From FY2007 to 2009, Dell reported a decrease in sales, gross margin, and operating income.

What caused Apple’s dramatic growth in sales and operating income and Dell’s comparatively sluggish performance? One of the most important factors was the introduction of innovative and stylish products, the linkages with iTunes, and expansion of the distinctive Apple stores. Among the company’s most important and most successful new products was the iPhone. Apple’s 2009 10-K indicates that iPhone unit sales grew 78 percent from 11.6 million units in 2008 to 20.7 million units in 2009. By 2009, the company’s revenues from iPhones and related services had grown to $13.0 billion and were nearly as large as the company’s $13.8 billion revenues from sales of Mac computers. The new products and linkages among the products not only increased demand but also increased the potential for higher pricing. As a result, gross profit margins and operating profit margins increased over the period because costs did not increase at the same pace as sales. Moreover, the company’s products revolutionized the delivery channel for music and video. The financial results reflect a successful execution of the company’s strategy to deliver integrated, innovative products by controlling the design and development of both hardware and software.

Dell continued to concentrate in the personal computer market, which arguably is in the market maturity stage of the product life cycle. Dell’s results are consistent with a market maturity stage where industry sales level off and competition increases so that industry profits decline. With increased competition, some companies cannot compete and drop out of the market.

Analysts often need to communicate the findings of their analysis in a written report. Their reports should communicate how conclusions were reached and why recommendations were made. For example, a report might present the following:3

- The purpose of the report, unless it is readily apparent.

- Relevant aspects of the business context:

- Economic environment (country, macro economy, sector).

- Financial and other infrastructure (accounting, auditing, rating agencies).

- Legal and regulatory environment (and any other material limitations on the company being analyzed).

- Evaluation of corporate governance and assessment of management strategy, including the company’s competitive advantage(s).

- Assessment of financial and operational data, including key assumptions in the analysis.

- Conclusions and recommendations, including limitations of the analysis and risks.

An effective narrative and well supported conclusions and recommendations are normally enhanced by using 3–10 years of data, as well as analytic techniques appropriate to the purpose of the report.

3. ANALYTICAL TOOLS AND TECHNIQUES

The tools and techniques presented in this section facilitate evaluations of company data. Evaluations require comparisons. It is difficult to say that a company’s financial performance was “good” without clarifying the basis for comparison. In assessing a company’s ability to generate and grow earnings and cash flow, and the risks related to those earnings and cash flows, the analyst draws comparisons to other companies (cross-sectional analysis) and over time (trend or time series analysis).

For example, an analyst may wish to compare the profitability of companies competing in a global industry. If the companies differ significantly in size and/or report their financial data in different currencies, comparing net income as reported is not useful. Ratios (which express one number in relation to another) and common-size financial statements can remove size as a factor and enable a more relevant comparison. To achieve comparability across companies reporting in different currencies, one approach is to translate all reported numbers into a common currency using exchange rates at the end of a period. Others may prefer to translate reported numbers using the average exchange rates during the period. Alternatively, if the focus is primarily on ratios, comparability can be achieved without translating the currencies.

The analyst may also want to examine comparable performance over time. Again, the nominal currency amounts of sales or net income may not highlight significant changes. However, using ratios (see Example 7-2), horizontal financial statements where quantities are stated in terms of a selected base year value, and graphs can make such changes more apparent. Another obstacle to comparison is differences in fiscal year end. To achieve comparability, one approach is to develop trailing twelve months data, which will be described in a section following. Finally, it should be noted that differences in accounting standards can limit comparability.

EXAMPLE 7-2 Ratio Analysis

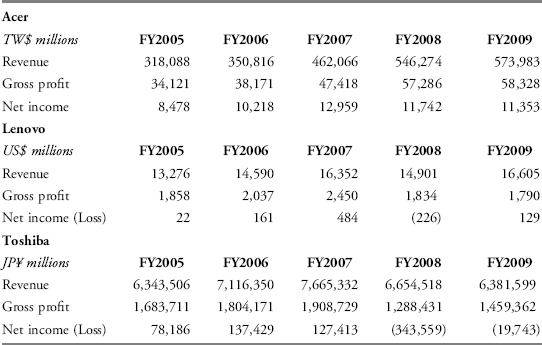

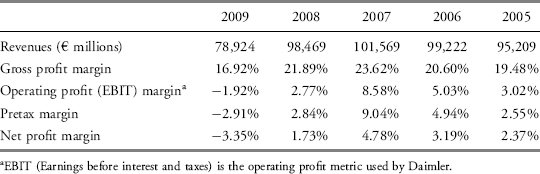

An analyst is examining the profitability of three Asian companies with large shares of the global personal computer market: Acer Inc. (Taiwan SE: ACER), Lenovo Group Limited (HKSE: 0992), and Toshiba Corporation (Tokyo SE: 6502). Taiwan-based Acer has pursued a strategy of selling its products at affordable prices. In contrast, China-based Lenovo aims to achieve higher selling prices by stressing the high engineering quality of its personal computers for business use. Japan-based Toshiba is a conglomerate with varied product lines in addition to computers. For its personal computer business, one aspect of Toshiba’s strategy has been to focus on laptops only, in contrast with other manufacturers that also make desktops. Acer reports in New Taiwan dollars (TW$), Lenovo reports in U.S. dollars (US$), and Toshiba reports in Japanese yen (JP¥). For Acer, fiscal year end is 31 December. For both Lenovo and Toshiba, fiscal year end is 31 March; thus, for these companies, FY2009 ended 31 March 2010.

The analyst collects the data shown in Exhibit 7-2. Use this information to answer the following questions:

1. Which of the three companies is largest based on the amount of revenue, in US$, reported in fiscal year 2009? For FY2009, assume the relevant, average exchange rates were 32.2 TW$/US$ and 92.5 JPY/US$.

2. Which company had the highest revenue growth from FY2005 to FY2009?

3. How do the companies compare, based on profitability?

Solution to 1: Toshiba is far larger than the other two companies based on FY2009 revenues in US$. Toshiba’s FY2009 revenues of US$69.0 billion are far higher than either Acer’s US$17.8 billion or Lenovo’s US$16.6 billion.

Acer: At the assumed average exchange rate of 32.2 TW$/US$, Acer’s FY2009 revenues are equivalent to US$17.8 billion (=TW$573.983billion÷32.2 TW$/US$).

Lenovo: Lenovo’s FY2009 revenues totaled US$16.6 billion.

Toshiba: At the assumed average exchange rate of 92.5 JP¥/US$, Toshiba’s revenues for FY2009 are equivalent to US$69.0 billion (=JPY 6,381.599 billion÷92.5 JP¥/US$).

Note: Comparing the size of companies reporting in different currencies requires translating reported numbers into a common currency using exchange rates at some point in time. This solution converts the revenues of Acer and Toshiba to billions of U.S. dollars using the average exchange rate of the fiscal period. It would be equally informative (and would yield the same conclusion) to convert the revenues of Acer and Lenovo to Japanese yen, or to convert the revenues of Toshiba and Lenovo to New Taiwan dollars.

Solution to 2: The growth in Acer’s revenue was much higher than either of the other two companies.

| Change in Revenue FY2009 versus FY2005 | Compound Annual Growth Rate from FY2005 to FY2009 | |

| Acer | 80.4% | 15.9% |

| Lenovo | 25.1% | 5.8% |

| Toshiba | 0.6% | 0.1% |

The table shows two growth metrics. Calculations are illustrated using the revenue data for Acer:

The change in Acer’s revenue for FY2009 versus FY2005 is 80.4 percent calculated as (573,983−318,088)÷318,088 or equivalently (573,983÷318,088)–1.

The compound annual growth rate in Acer’s revenue from FY2005 to FY2009 is 15.9 percent, calculated using a financial calculator with the following inputs: Present Value=−318,088; Future value=573,983; N=4; Payment=0; and then Interest=? to solve for growth.

Calculation of the compound annual growth rate can also be expressed as follows: [(Ending value÷Beginning value)(1/number of periods)]−1=[(573,983÷318,088)(1/4) − 1=0.159 or 15.9 percent.

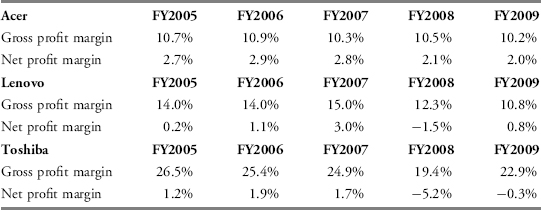

Solution to 3: Profitability can be assessed by comparing the amount of gross profit to revenue and the amount of net income to revenue. The following table presents these two profitability ratios—gross profit margin (gross profit divided by revenue) and net profit margin (net income divided by revenue)—for each year.

The net profit margins indicate that Acer has been the most profitable of the three companies. The company’s net profit margin was somewhat lower in the most recent two years (only 2.1 percent and 2.0 percent in FY2008 and FY2009, respectively, compared to 2.7 percent, 2.9 percent, and 2.8 percent in FYs 2005, 2006, and 2007, respectively), but has nonetheless remained positive and has remained higher than the competing companies.

Acer’s gross profit margin has remained consistently above 10 percent in all five fiscal years. In contrast, Lenovo’s gross profit margin has declined markedly over the five-year period, but remains higher than Acer’s, which is consistent with the company’s strategic objective to achieve higher selling prices by stressing the high engineering quality of its personal computers. However, Lenovo’s net profit margin has typically been lower than Acer’s. Further analysis is needed to determine the cause of Lenovo’s gross profitability decline over the period FY2005 to 2009 (lower selling prices and/or higher costs), to assess whether this decline is likely to persist in future years, and to determine the reason Lenovo’s net profit margins are generally lower than Acer’s despite Lenovo’s higher gross profit margins.

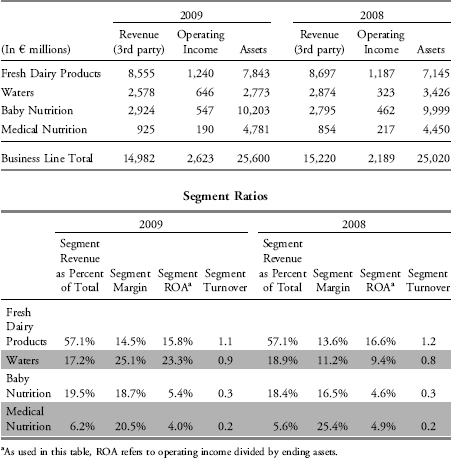

Because Toshiba is a conglomerate, profit ratios based on data for the entire company give limited information about the company’s personal computer business. Ratios based on segment data would likely be more useful than profit ratios for the entire company. Based on the aggregate information, Toshiba’s gross profit margins are higher than either Acer’s or Lenovo’s gross profit margins, whereas Toshiba’s net profit margins are generally lower than the net profit margins of either of the other two companies.

Section 3.1 describes the tools and techniques of ratio analysis in more detail. Sections 3.2 to 3.4 describe other tools and techniques.

3.1. Ratios

There are many relationships between financial accounts and between expected relationships from one point in time to another. Ratios are a useful way of expressing these relationships. Ratios express one quantity in relation to another (usually as a quotient).

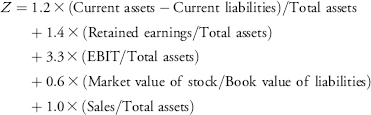

Extensive academic research has examined the importance of ratios in predicting stock returns (Ou and Penman, 1989; Abarbanell and Bushee, 1998) or credit failure (Altman, 1968; Ohlson, 1980; Hopwood et al., 1994). This research has found that financial statement ratios are effective in selecting investments and in predicting financial distress. Practitioners routinely use ratios to derive and communicate the value of companies and securities.

Several aspects of ratio analysis are important to understand. First, the computed ratio is not “the answer.” The ratio is an indicator of some aspect of a company’s performance, telling what happened but not why it happened. For example, an analyst might want to answer the question: Which of two companies was more profitable? As demonstrated in the previous example, the net profit margin, which expresses profit relative to revenue, can provide insight into this question. Net profit margin is calculated by dividing net income by revenue:4

![]()

Assume Company A has €100,000 of net income and Company B has €200,000 of net income. Company B generated twice as much income as Company A, but was it more profitable? Assume further that Company A has €2,000,000 of revenue, and thus a net profit margin of 5 percent, and Company B has €6,000,000 of revenue, and thus a net profit margin of 3.33 percent. Expressing net income as a percentage of revenue clarifies the relationship: For each €100 of revenue, Company A earns €5 in net income, whereas Company B earns only €3.33 for each €100 of revenue. So, we can now answer the question of which company was more profitable in percentage terms: Company A was more profitable, as indicated by its higher net profit margin of 5 percent. Note that Company A was more profitable despite the fact that Company B reported higher absolute amounts of net income and revenue. However, this ratio by itself does not tell us why Company A has a higher profit margin. Further analysis is required to determine the reason (perhaps higher relative sales prices or better cost control or lower effective tax rates).

Company size sometimes confers economies of scale, so the absolute amounts of net income and revenue are useful in financial analysis. However, ratios reduce the effect of size, which enhances comparisons between companies and over time.

A second important aspect of ratio analysis is that differences in accounting policies (across companies and across time) can distort ratios, and a meaningful comparison may, therefore, involve adjustments to the financial data. Third, not all ratios are necessarily relevant to a particular analysis. The ability to select a relevant ratio or ratios to answer the research question is an analytical skill. Finally, as with financial analysis in general, ratio analysis does not stop with computation; interpretation of the result is essential. In practice, differences in ratios across time and across companies can be subtle, and interpretation is situation specific.

3.1.1. The Universe of Ratios

There are no authoritative bodies specifying exact formulas for computing ratios or providing a standard, comprehensive list of ratios. Formulas and even names of ratios often differ from analyst to analyst or from database to database. The number of different ratios that can be created is practically limitless. There are, however, widely accepted ratios that have been found to be useful. Section 4 of this chapter will focus primarily on these broad classes and commonly accepted definitions of key ratios. However, the analyst should be aware that different ratios may be used in practice and that certain industries have unique ratios tailored to the characteristics of that industry. When faced with an unfamiliar ratio, the analyst can examine the underlying formula to gain insight into what the ratio is measuring. For example, consider the following ratio formula:

![]()

Never having seen this ratio, an analyst might question whether a result of 12 percent is better than 8 percent. The answer can be found in the ratio itself. The numerator is operating income and the denominator is average total assets, so the ratio can be interpreted as the amount of operating income generated per unit of assets. For every €100 of average total assets, generating €12 of operating income is better than generating €8 of operating income. Furthermore, it is apparent that this particular ratio is an indicator of profitability (and, to a lesser extent, efficiency in use of assets in generating operating profits). When facing a ratio for the first time, the analyst should evaluate the numerator and denominator to assess what the ratio is attempting to measure and how it should be interpreted. This is demonstrated in Example 7-3.

EXAMPLE 7-3 Interpreting a Financial Ratio

A U.S. insurance company reports that its “combined ratio” is determined by dividing losses and expenses incurred by net premiums earned. It reports the following combined ratios:

Explain what this ratio is measuring and compare the results reported for each of the years shown in the chart. What other information might an analyst want to review before making any conclusions on this information?

Solution: The combined ratio is a profitability measure. The ratio is explaining how much costs (losses and expenses) were incurred for every dollar of revenue (net premiums earned). The underlying formula indicates that a lower ratio is better. The Year 5 ratio of 90.1 percent means that for every dollar of net premiums earned, the costs were $0.901, yielding a gross profit of $0.099. Ratios greater than 100 percent indicate an overall loss. A review of the data indicates that there does not seem to be a consistent trend in this ratio. Profits were achieved in Years 5 and 3. The results for Years 4 and 2 show the most significant costs at approximately 104 percent.

The analyst would want to discuss this data further with management and understand the characteristics of the underlying business. He or she would want to understand why the results are so volatile. The analyst would also want to determine what should be used as a benchmark for this ratio.

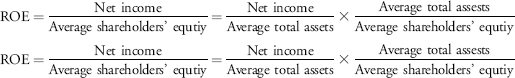

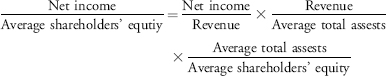

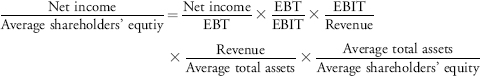

The Operating income/Average total assets ratio shown previously is one of many versions of the return on assets (ROA) ratio. Note that there are other ways of specifying this formula based on how assets are defined. Some financial ratio databases compute ROA using the ending value of assets rather than average assets. In limited cases, one may also see beginning assets in the denominator. Which one is right? It depends on what you are trying to measure and the underlying company trends. If the company has a stable level of assets, the answer will not differ greatly under the three measures of assets (beginning, average, and ending). However, if the assets are growing (or shrinking), the results will differ among the three measures. When assets are growing, operating income divided by ending assets may not make sense because some of the income would have been generated before some assets were purchased, and this would understate the company’s performance. Similarly, if beginning assets are used, some of the operating income later in the year may have been generated only because of the addition of assets; therefore, the ratio would overstate the company’s performance. Because operating income occurs throughout the period, it generally makes sense to use some average measure of assets. A good general rule is that when an income statement or cash flow statement number is in the numerator of a ratio and a balance sheet number is in the denominator, then an average should be used for the denominator. It is generally not necessary to use averages when only balance sheet numbers are used in both the numerator and denominator because both are determined as of the same date. However, in some instances, even ratios that only use balance sheet data may use averages. For example, return on equity (ROE), which is defined as net income divided by average shareholders’ equity, can be decomposed into other ratios, some of which only use balance sheet data. In decomposing ROE into component ratios, if an average is used in one of the component ratios then it should be used in the other component ratios. The decomposition of ROE is discussed further in Section 4.6.2.

If an average is used, judgment is also required about what average should be used. For simplicity, most ratio databases use a simple average of the beginning and end-of-year balance sheet amounts. If the company’s business is seasonal so that levels of assets vary by interim period (semiannual or quarterly), then it may be beneficial to take an average over all interim periods, if available. (If the analyst is working within a company and has access to monthly data, this can also be used.)

3.1.2. Value, Purposes, and Limitations of Ratio Analysis

The value of ratio analysis is that it enables a financial analyst to evaluate past performance, assess the current financial position of the company, and gain insights useful for projecting future results. As noted previously, the ratio itself is not “the answer” but is an indicator of some aspect of a company’s performance. Financial ratios provide insights into:

- Microeconomic relationships within a company that help analysts project earnings and free cash flow.

- A company’s financial flexibility, or ability to obtain the cash required to grow and meet its obligations, even if unexpected circumstances develop.

- Management’s ability.

- Changes in the company and/or industry over time.

- Comparability with peer companies or the relevant industry(ies).

There are also limitations to ratio analysis. Factors to consider include:

- The heterogeneity or homogeneity of a company’s operating activities. Companies may have divisions operating in many different industries. This can make it difficult to find comparable industry ratios to use for comparison purposes.

- The need to determine whether the results of the ratio analysis are consistent. One set of ratios may indicate a problem, whereas another set may indicate that the potential problem is only short term in nature.

- The need to use judgment. A key issue is whether a ratio for a company is within a reasonable range. Although financial ratios are used to help assess the growth potential and risk of a company, they cannot be used alone to directly value a company or its securities, or to determine its creditworthiness. The entire operation of the company must be examined, and the external economic and industry setting in which it is operating must be considered when interpreting financial ratios.

- The use of alternative accounting methods. Companies frequently have latitude when choosing certain accounting methods. Ratios taken from financial statements that employ different accounting choices may not be comparable unless adjustments are made. Some important accounting considerations include the following:

- FIFO (first in, first out), LIFO (last in, first out), or average cost inventory valuation methods (IFRS does not allow LIFO).

- Cost or equity methods of accounting for unconsolidated affiliates.

- Straight line or accelerated methods of depreciation.

- Capital or operating lease treatment.

The expanding use of IFRS and the ongoing convergence between IFRS and U.S. GAAP seeks to make the financial statements of different companies comparable and may overcome some of these difficulties. Nonetheless, there will remain accounting choices that the analyst must consider.

3.1.3. Sources of Ratios

Ratios may be computed using data obtained directly from companies’ financial statements or from a database such as Bloomberg, Compustat, FactSet, or Thomson Reuters. The information provided by the database may include information as reported in companies’ financial statements and ratios calculated based on the information. These databases are popular because they provide easy access to many years of historical data so that trends over time can be examined. They also allow for ratio calculations based on periods other than the company’s fiscal year, such as for the trailing 12 months (TTM) or most recent quarter (MRQ).

EXAMPLE 7-4 Trailing Twelve Months

On 15 July, an analyst is examining a company with a fiscal year ending on 31 December. Use the following data to calculate the company’s trailing 12-month earnings (for the period ended 30 June 2010).

- Earnings for the year ended 31 December, 2009: $1,200

- Earnings for the six months ended 30 June 2009: $550

- Earnings for the six months ended 30 June 2010: $750

Solution: The company’s trailing 12 months earnings is $1,400, calculated as $1,200 − $550=$750.

Analysts should be aware that the underlying formulas for ratios may differ by vendor. The formula used should be obtained from the vendor, and the analyst should determine whether any adjustments are necessary. Furthermore, database providers often exercise judgment when classifying items. For example, operating income may not appear directly on a company’s income statement, and the vendor may use judgment to classify income statement items as “operating” or “nonoperating.” Variation in such judgments would affect any computation involving operating income. It is therefore a good practice to use the same source for data when comparing different companies or when evaluating the historical record of a single company. Analysts should verify the consistency of formulas and data classifications by the data source. Analysts should also be mindful of the judgments made by a vendor in data classifications and refer back to the source financial statements until they are comfortable that the classifications are appropriate.

Systems are under development that collect financial data from regulatory filings and can automatically compute ratios. The eXtensible Business Reporting Language (XBRL) is a mechanism that attaches “smart tags” to financial information (e.g., total assets), so that software can automatically collect the data and perform desired computations. The organization developing XBRL (www.xbrl.org) is an international nonprofit consortium of over 600 members from companies, associations, and agencies, including the International Accounting Standards Board. Many stock exchanges and regulatory agencies around the world now use XBRL for receiving and distributing public financial reports from listed companies.

Analysts can compare a subject company to similar (peer) companies in these databases or use aggregate industry data. For nonpublic companies, aggregate industry data can be obtained from such sources as Annual Statement Studies by the Risk Management Association or Dun & Bradstreet. These publications typically provide industry data with companies sorted into quartiles. By definition, 25 percent of companies’ ratios fall within the lowest quartile, 25 percent have ratios between the lower quartile and median value, and so on. Analysts can then determine a company’s relative standing in the industry.

3.2. Common-Size Analysis

Common-size analysis involves expressing financial data, including entire financial statements, in relation to a single financial statement item, or base. Items used most frequently as the bases are total assets or revenue. In essence, common-size analysis creates a ratio between every financial statement item and the base item.

Common-size analysis was demonstrated in chapters for the income statement, balance sheet, and cash flow statement. In this section, we present common-size analysis of financial statements in greater detail and include further discussion of their interpretation.

3.2.1. Common-Size Analysis of the Balance Sheet

A vertical5 common-size balance sheet, prepared by dividing each item on the balance sheet by the same period’s total assets and expressing the results as percentages, highlights the composition of the balance sheet. What is the mix of assets being used? How is the company financing itself? How does one company’s balance sheet composition compare with that of peer companies, and what are the reasons for any differences?

A horizontal common-size balance sheet, prepared by computing the increase or decrease in percentage terms of each balance sheet item from the prior year or prepared by dividing the quantity of each item by a base year quantity of the item, highlights changes in items. These changes can be compared to expectations. The following section on trend analysis will illustrate a horizontal common-size balance sheet.

Exhibit 7-3 presents a vertical common-size (partial) balance sheet for a hypothetical company in two time periods. In this example, receivables have increased from 35 percent to 57 percent of total assets and the ratio has increased by 63 percent from Period 1 to Period 2. What are possible reasons for such an increase? The increase might indicate that the company is making more of its sales on a credit basis rather than a cash basis, perhaps in response to some action taken by a competitor. Alternatively, the increase in receivables as a percentage of assets may have occurred because of a change in another current asset category, for example, a decrease in the level of inventory; the analyst would then need to investigate why that asset category has changed. Another possible reason for the increase in receivables as a percentage of assets is that the company has lowered its credit standards, relaxed its collection procedures, or adopted more aggressive revenue recognition policies. The analyst can turn to other comparisons and ratios (e.g., comparing the rate of growth in accounts receivable with the rate of growth in sales) to help determine which explanation is most likely.

EXHIBIT 7-3 Vertical Common-Size (Partial) Balance Sheet for a Hypothetical Company

| Period 1 Percent of Total Assets | Period 2 Percent of Total Assets | |

| Cash | 25 | 15 |

| Receivables | 35 | 57 |

| Inventory | 35 | 20 |

| Fixed assets, net of depreciation | 5 | 8 |

| Total assets | 100 | 100 |

3.2.2. Common-Size Analysis of the Income Statement

A vertical common-size income statement divides each income statement item by revenue, or sometimes by total assets (especially in the case of financial institutions). If there are multiple revenue sources, a decomposition of revenue in percentage terms is useful. Exhibit 7-4 presents a hypothetical company’s vertical common-size income statement in two time periods. Revenue is separated into the company’s four services, each shown as a percentage of total revenue.

In this example, revenues from Service A have become a far greater percentage of the company’s total revenue (30 percent in Period 1 and 45 percent in Period 2). What are possible reasons for and implications of this change in business mix? Did the company make a strategic decision to sell more of Service A, perhaps because it is more profitable? Apparently not, because the company’s earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA) declined from 53 percent of sales to 45 percent, so other possible explanations should be examined. In addition, we note from the composition of operating expenses that the main reason for this decline in profitability is that salaries and employee benefits have increased from 15 percent to 25 percent of total revenue. Are more highly compensated employees required for Service A? Were higher training costs incurred in order to increase revenues from Service A? If the analyst wants to predict future performance, the causes of these changes must be understood.

In addition, Exhibit 7-4 shows that the company’s income tax as a percentage of sales has declined dramatically (from 15 percent to 8 percent). Furthermore, taxes as a percentage of earnings before tax (EBT) (the effective tax rate, which is usually the more relevant comparison), have decreased from 36 percent (= 15/42) to 24 percent (= 8/34). Is Service A, which in Period 2 is a greater percentage of total revenue, provided in a jurisdiction with lower tax rates? If not, what is the explanation for the change in effective tax rate?

The observations based on Exhibit 7-4 summarize the issues that can be raised through analysis of the vertical common-size income statement.

EXHIBIT 7-4 Vertical Common-Size Income Statement for Hypothetical Company

| Period 1 Percent of Total Revenue | Period 2 Percent of Total Revenue | |

| Revenue source: Service A | 30 | 45 |

| Revenue source: Service B | 23 | 20 |

| Revenue source: Service C | 30 | 30 |

| Revenue source: Service D | 17 | 5 |

| Total revenue | 100 | 100 |

| Operating expenses (excluding depreciation) | ||

| Salaries and employee benefits | 15 | 25 |

| Administrative expenses | 22 | 20 |

| Rent expense | 10 | 10 |

| EBITDA | 53 | 45 |

| Depreciation and amortization | 4 | 4 |

| EBIT | 49 | 41 |

| Interest paid | 7 | 7 |

| EBT | 42 | 34 |

| Income tax provision | 15 | 8 |

| Net income | 27 | 26 |

EBIT=earnings before interest and tax.

3.2.3. Cross-Sectional Analysis

As noted previously, ratios and common-size statements derive part of their meaning through comparison to some benchmark. Cross-sectional analysis (sometimes called “relative analysis”) compares a specific metric for one company with the same metric for another company or group of companies, allowing comparisons even though the companies might be of significantly different sizes and/or operate in different currencies. This is illustrated in Exhibit 7-5.

EXHIBIT 7-5 Vertical Common-Size (Partial) Balance Sheet for Two Hypothetical Companies

| Assets | Company 1 Percent of Total Assets | Company 2 Percent of Total Assets |

| Cash | 38 | 12 |

| Receivables | 33 | 55 |

| Inventory | 27 | 24 |

| Fixed assets net of depreciation | 1 | 2 |

| Investments | 1 | 7 |

| Total Assets | 100 | 100 |

Exhibit 7-5 presents a vertical common-size (partial) balance sheet for two hypothetical companies at the same point in time. Company 1 is clearly more liquid (liquidity is a function of how quickly assets can be converted into cash) than Company 2, which has only 12 percent of assets available as cash, compared with the highly liquid Company 1, which has 38 percent of assets available as cash. Given that cash is generally a relatively low-yielding asset and thus not a particularly efficient use of excess funds, why does Company 1 hold such a large percentage of total assets in cash? Perhaps the company is preparing for an acquisition, or maintains a large cash position as insulation from a particularly volatile operating environment. Another issue highlighted by the comparison in this example is the relatively high percentage of receivables in Company 2’s assets, which may indicate a greater proportion of credit sales, overall changes in asset composition, lower credit or collection standards, or aggressive accounting policies.

3.2.4. Trend Analysis6

When looking at financial statements and ratios, trends in the data, whether they are improving or deteriorating, are as important as the current absolute or relative levels. Trend analysis provides important information regarding historical performance and growth and, given a sufficiently long history of accurate seasonal information, can be of great assistance as a planning and forecasting tool for management and analysts.

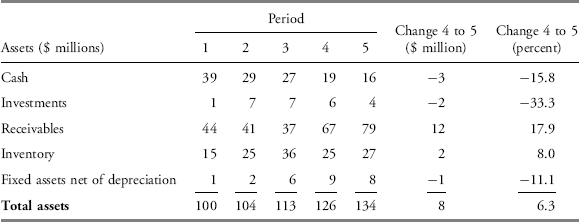

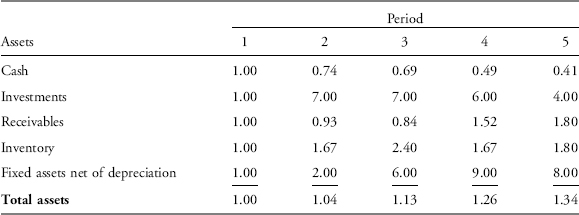

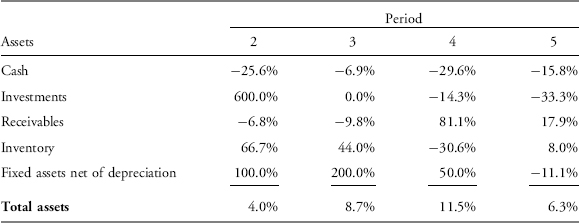

Exhibit 7-6A presents a partial balance sheet for a hypothetical company over five periods. The last two columns of the table show the changes for Period 5 compared with Period 4, expressed both in absolute currency (in this case, dollars) and in percentages. A small percentage change could hide a significant currency change and vice versa, prompting the analyst to investigate the reasons despite one of the changes being relatively small. In this example, the largest percentage change was in investments, which decreased by 33.3 percent.7 However, an examination of the absolute currency amount of changes shows that investments changed by only $2 million, and the more significant change was the $12 million increase in receivables.

Another way to present data covering a period of time is to show each item in relation to the same item in a base year (i.e., a horizontal common-size balance sheet). Exhibits 7-6B and 7-6C illustrate alternative presentations of horizontal common-size balance sheets. Exhibit 7-6B presents the information from the same partial balance sheet as in Exhibit 7-6A, but indexes each item relative to the same item in Period 1. For example, in Period 2, the company had $29 million cash, which is 74 percent or 0.74 of the amount of cash it had in Period 1. Expressed as an index relative to Period 1, where each item in Period 1 is given a value of 1.00, the value in Period 2 would be 0.74 ($29/$39=0.74). In Period 3, the company had $27 million cash, which is 69 percent of the amount of cash it had in Period 1 ($27/$39=0.69).

Exhibit 7-6C presents the percentage change in each item, relative to the previous year. For example, the change in cash from Period 1 to Period 2 was −25.6 percent ($29/$39 − 1=–0.256), and the change in cash from Period 2 to Period 3 was −6.9 percent ($27/$29 − 1=–0.069). An analyst will select the horizontal common-size balance that addresses the particular period of interest. Exhibit 7-6B clearly highlights that in Period 5 compared to Period 1, the company has less than half the amount of cash, four times the amount of investments, and eight times the amount of property, plant, and equipment. Exhibit 7-6C highlights year-to-year changes: For example, cash has declined in each period. Presenting data this way highlights significant changes. Again, note that a mathematically big change is not necessarily an important change. For example, fixed assets increased 100 percent, i.e., doubled between Period 1 and 2; however, as a proportion of total assets, fixed assets increased from 1 percent of total assets to 2 percent of total assets. The company’s working capital assets (receivables and inventory) are a far higher proportion of total assets and would likely warrant more attention from an analyst.

An analysis of horizontal common-size balance sheets highlights structural changes that have occurred in a business. Past trends are obviously not necessarily an accurate predictor of the future, especially when the economic or competitive environment changes. An examination of past trends is more valuable when the macroeconomic and competitive environments are relatively stable and when the analyst is reviewing a stable or mature business. However, even in less stable contexts, historical analysis can serve as a basis for developing expectations. Understanding of past trends is helpful in assessing whether these trends are likely to continue or if the trend is likely to change direction.

EXHIBIT 7-6A Partial Balance Sheet for a Hypothetical Company over Five Periods

EXHIBIT 7-6B Horizontal Common-Size (Partial) Balance Sheet for a Hypothetical Company over Five Periods, with Each Item Expressed Relative to the Same Item in Period One

EXHIBIT 7-6C Horizontal Common-Size (Partial) Balance Sheet for a Hypothetical Company over Five Periods, with Percent Change in Each Item Relative to the Prior Period

One measure of success is for a company to grow at a rate greater than the rate of the overall market in which it operates. Companies that grow slowly may find themselves unable to attract equity capital. Conversely, companies that grow too quickly may find that their administrative and management information systems cannot keep up with the rate of expansion.

3.2.5. Relationships among Financial Statements

Trend data generated by a horizontal common-size analysis can be compared across financial statements. For example, the growth rate of assets for the hypothetical company in Exhibit 7-6 can be compared with the company’s growth in revenue over the same period of time. If revenue is growing more quickly than assets, the company may be increasing its efficiency (i.e., generating more revenue for every dollar invested in assets).

As another example, consider the following year-over-year percentage changes for a hypothetical company:

| Revenue | +20% |

| Net income | +25% |

| Operating cash flow | −10% |

| Total assets | +30% |

Net income is growing faster than revenue, which indicates increasing profitability. However, the analyst would need to determine whether the faster growth in net income resulted from continuing operations or from nonoperating, nonrecurring items. In addition, the 10 percent decline in operating cash flow despite increasing revenue and net income clearly warrants further investigation because it could indicate a problem with earnings quality (perhaps aggressive reporting of revenue). Lastly, the fact that assets have grown faster than revenue indicates the company’s efficiency may be declining. The analyst should examine the composition of the increase in assets and the reasons for the changes. Example 7-5 illustrates a company where comparisons of trend data from different financial statements were actually indicative of aggressive accounting policies.

EXAMPLE 7-5 Use of Comparative Growth Information8

In July 1996, Sunbeam, a U.S. company, brought in new management to turn the company around. In the following year, 1997, using 1996 as the base, the following was observed based on reported numbers:

| Revenue | +19% |

| Inventory | +58% |

| Receivables | +38% |

It is generally more desirable to observe inventory and receivables growing at a slower (or similar) rate compared to revenue growth. Receivables growing faster than revenue can indicate operational issues, such as lower credit standards or aggressive accounting policies for revenue recognition. Similarly, inventory growing faster than revenue can indicate an operational problem with obsolescence or aggressive accounting policies, such as an improper overstatement of inventory to increase profits.

In this case, the explanation lay in aggressive accounting policies. Sunbeam was later charged by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission with improperly accelerating the recognition of revenue and engaging in other practices, such as billing customers for inventory prior to shipment.

3.3. The Use of Graphs as an Analytical Tool

Graphs facilitate comparison of performance and financial structure over time, highlighting changes in significant aspects of business operations. In addition, graphs provide the analyst (and management) with a visual overview of risk trends in a business. Graphs may also be used effectively to communicate the analyst’s conclusions regarding financial condition and risk management aspects.

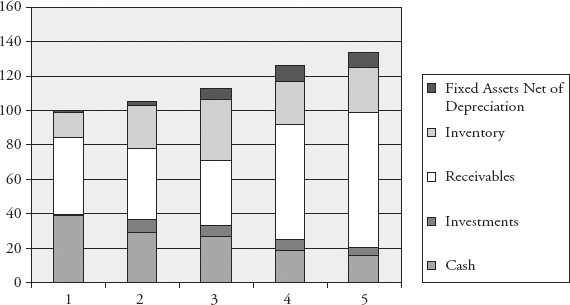

Exhibit 7-7 presents the information from Exhibit 7-6A in a stacked column format. The graph makes the significant decline in cash and growth in receivables (both in absolute terms and as a percentage of assets) readily apparent. In Exhibit 7-7, the vertical axis shows US$ millions and the horizontal axis denotes the period.

Choosing the appropriate graph to communicate the most significant conclusions of a financial analysis is a skill. In general, pie graphs are most useful to communicate the composition of a total value (e.g., assets over a limited amount of time, say one or two periods). Line graphs are useful when the focus is on the change in amount for a limited number of items over a relatively longer time period. When the composition and amounts, as well as their change over time, are all important, a stacked column graph can be useful.

EXHIBIT 7-7 Stacked Column Graph of Asset Composition of Hypothetical Company over Five Periods

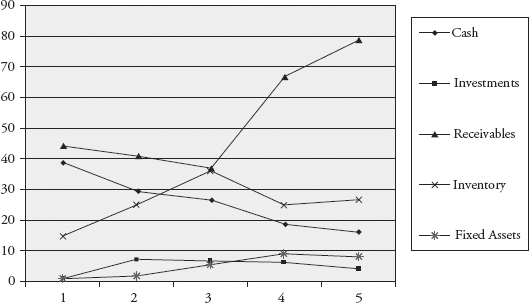

When comparing Period 5 with Period 4, the growth in receivables appears to be within normal bounds; but when comparing Period 5 with earlier periods, the dramatic growth becomes apparent. In the same manner, a simple line graph will also illustrate the growth trends in key financial variables. Exhibit 7-8 presents the information from Exhibit 7-6A as a line graph, illustrating the growth of assets of a hypothetical company over five periods. The steady decline in cash, volatile movements of inventory, and dramatic growth of receivables is clearly illustrated. Again, the vertical axis is shown in US$ millions and the horizontal axis denotes periods.

EXHIBIT 7-8 Line Graph of Growth of Assets of Hypothetical Company over Five Periods

3.4. Regression Analysis

When analyzing the trend in a specific line item or ratio, frequently it is possible simply to visually evaluate the changes. For more complex situations, regression analysis can help identify relationships (or correlation) between variables. For example, a regression analysis could relate a company’s sales to GDP over time, providing insight into whether the company is cyclical. In addition, the statistical relationship between sales and GDP could be used as a basis for forecasting sales.

Other examples include the relationship between a company’s sales and inventory over time, or the relationship between hotel occupancy and a company’s hotel revenues. In addition to providing a basis for forecasting, regression analysis facilitates identification of items or ratios that are not behaving as expected, given historical statistical relationships.

4. COMMON RATIOS USED IN FINANCIAL ANALYSIS

In the previous section, we focused on ratios resulting from common-size analysis. In this section, we expand the discussion to include other commonly used financial ratios and the broad classes into which they are categorized. There is some overlap with common-size financial statement ratios. For example, a common indicator of profitability is the net profit margin, which is calculated as net income divided by sales. This ratio appears on a vertical common-size income statement. Other ratios involve information from multiple financial statements or even data from outside the financial statements.

Because of the large number of ratios, it is helpful to think about ratios in terms of broad categories based on what aspects of performance a ratio is intended to detect. Financial analysts and data vendors use a variety of categories to classify ratios. The category names and the ratios included in each category can differ. Common ratio categories include activity, liquidity, solvency, profitability, and valuation. These categories are summarized in Exhibit 7-9. Each category measures a different aspect of the company’s business, but all are useful in evaluating a company’s overall ability to generate cash flows from operating its business and the associated risks.

EXHIBIT 7-9 Categories of Financial Ratios

| Category | Description |

| Activity | Activity ratios measure how efficiently a company performs day-to-day tasks, such as the collection of receivables and management of inventory. |

| Liquidity | Liquidity ratios measure the company’s ability to meet its short-term obligations. |

| Solvency | Solvency ratios measure a company’s ability to meet long-term obligations. Subsets of these ratios are also known as “leverage” and “long-term debt” ratios. |

| Profitability | Profitability ratios measure the company’s ability to generate profits from its resources (assets). |

| Valuation | Valuation ratios measure the quantity of an asset or flow (e.g., earnings) associated with ownership of a specified claim (e.g., a share or ownership of the enterprise). |

These categories are not mutually exclusive; some ratios are useful in measuring multiple aspects of the business. For example, an activity ratio measuring how quickly a company collects accounts receivable is also useful in assessing the company’s liquidity because collection of revenues increases cash. Some profitability ratios also reflect the operating efficiency of the business. In summary, analysts appropriately use certain ratios to evaluate multiple aspects of the business. Analysts also need to be aware of variations in industry practice in the calculation of financial ratios. In the text that follows, alternative views on ratio calculations are often provided.

4.1. Interpretation and Context

Financial ratios can only be interpreted in the context of other information, including benchmarks. In general, the financial ratios of a company are compared with those of its major competitors (cross-sectional and trend analysis) and to the company’s prior periods (trend analysis). The goal is to understand the underlying causes of divergence between a company’s ratios and those of the industry. Even ratios that remain consistent require understanding because consistency can sometimes indicate accounting policies selected to smooth earnings. An analyst should evaluate financial ratios based on the following:

1. Company goals and strategy: Actual ratios can be compared with company objectives to determine whether objectives are being attained and whether the results are consistent with the company’s strategy.

2. Industry norms (cross-sectional analysis): A company can be compared with others in its industry by relating its financial ratios to industry norms or to a subset of the companies in an industry. When industry norms are used to make judgments, care must be taken because:

- Many ratios are industry specific, and not all ratios are important to all industries.

- Companies may have several different lines of business. This will cause aggregate financial ratios to be distorted. It is better to examine industry-specific ratios by lines of business.

- Differences in accounting methods used by companies can distort financial ratios.

- Differences in corporate strategies can affect certain financial ratios.

3. Economic conditions: For cyclical companies, financial ratios tend to improve when the economy is strong and weaken during recessions. Therefore, financial ratios should be examined in light of the current phase of the business cycle.

The following sections discuss activity, liquidity, solvency, and profitability ratios in turn. Selected valuation ratios are presented later in the section on equity analysis.

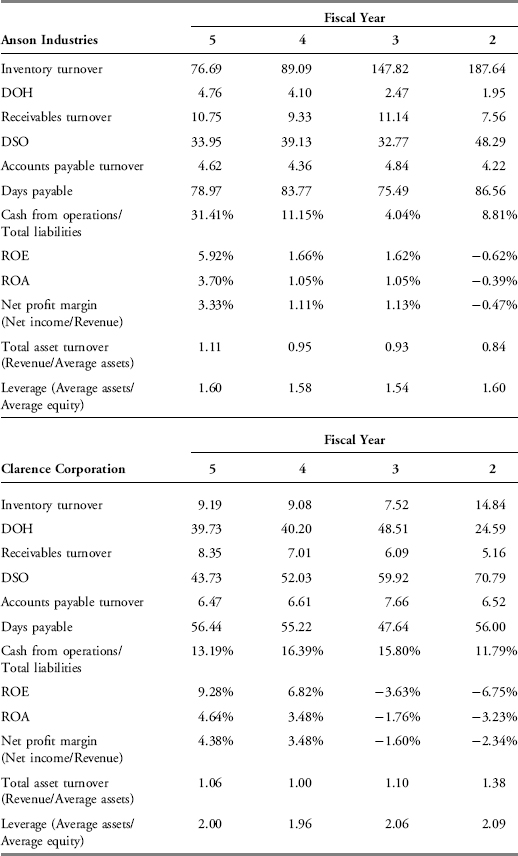

4.2. Activity Ratios

Activity ratios are also known as asset utilization ratios or operating efficiency ratios. This category is intended to measure how well a company manages various activities, particularly how efficiently it manages its various assets. Activity ratios are analyzed as indicators of ongoing operational performance—how effectively assets are used by a company. These ratios reflect the efficient management of both working capital and longer-term assets. As noted, efficiency has a direct impact on liquidity (the ability of a company to meet its short-term obligations), so some activity ratios are also useful in assessing liquidity.

4.2.1. Calculation of Activity Ratios

Exhibit 7-10 presents the most commonly used activity ratios. The exhibit shows the numerator and denominator of each ratio.

EXHIBIT 7-10 Definitions of Commonly Used Activity Ratios

| Activity Ratios | Numerator | Denominator |

| Inventory turnover | Cost of sales or cost of goods sold | Average inventory |

| Days of inventory on hand (DOH) | Number of days in period | Inventory turnover |

| Receivables turnover | Revenue | Average receivables |

| Days of sales outstanding (DSO) | Number of days in period | Receivables turnover |

| Payables turnover | Purchases | Average trade payables |

| Number of days of payables | Number of days in period | Payables turnover |

| Working capital turnover | Revenue | Average working capital |

| Fixed asset turnover | Revenue | Average net fixed assets |

| Total asset turnover | Revenue | Average total assets |

Activity ratios measure how efficiently the company utilizes assets. They generally combine information from the income statement in the numerator with balance sheet items in the denominator. Because the income statement measures what happened during a period whereas the balance sheet shows the condition only at the end of the period, average balance sheet data are normally used for consistency. For example, to measure inventory management efficiency, cost of sales or cost of goods sold (from the income statement) is divided by average inventory (from the balance sheet). Most databases, such as Bloomberg and Baseline, use this averaging convention when income statement and balance sheet data are combined. These databases typically average only two points: the beginning of the year and the end of the year. The examples that follow based on annual financial statements illustrate that practice. However, some analysts prefer to average more observations if they are available, especially if the business is seasonal. If a semiannual report is prepared, an average can be taken over three data points (beginning, middle, and end of year). If quarterly data are available, a five-point average can be computed (beginning of year and end of each quarterly period) or a four-point average using the end of each quarterly period. Note that if the company’s year ends at a low or high point for inventory for the year, there can still be bias in using three or five data points, because the beginning and end of year occur at the same time of the year and are effectively double counted.

Because cost of goods sold measures the cost of inventory that has been sold, this ratio measures how many times per year the entire inventory was theoretically turned over, or sold. (We say that the entire inventory was “theoretically” sold because in practice companies do not generally sell out their entire inventory.) If, for example, a company’s cost of goods sold for a recent year was €120,000 and its average inventory was €10,000, the inventory turnover ratio would be 12. The company theoretically turns over (i.e., sells) its entire inventory 12 times per year (i.e., once a month). (Again, we say “theoretically” because in practice the company likely carries some inventory from one month into another.) Turnover can then be converted to days of inventory on hand (DOH) by dividing inventory turnover into the number of days in the accounting period. In this example, the result is a DOH of 30.42 (365/12), meaning that, on average, the company’s inventory was on hand for about 30 days, or, equivalently, the company kept on hand about 30 days’ worth of inventory, on average, during the period.

Activity ratios can be computed for any annual or interim period, but care must be taken in the interpretation and comparison across periods. For example, if the same company had cost of goods sold for the first quarter (90 days) of the following year of €35,000 and average inventory of €11,000, the inventory turnover would be 3.18 times. However, this turnover rate is 3.18 times per quarter, which is not directly comparable to the 12 times per year in the preceding year. In this case, we can annualize the quarterly inventory turnover rate by multiplying the quarterly turnover by 4 (12 months/3 months; or by 4.06, using 365 days/90 days) for comparison to the annual turnover rate. So, the quarterly inventory turnover is equivalent to a 12.72 annual inventory turnover (or 12.91 if we annualize the ratio using a 90-day quarter and a 365-day year). To compute the DOH using quarterly data, we can use the quarterly turnover rate and the number of days in the quarter for the numerator—or, we can use the annualized turnover rate and 365 days; either results in DOH of around 28.3, with slight differences due to rounding (90/3.18=28.30 and 365/12.91=28.27). Another time-related computational detail is that for companies using a 52/53-week annual period and for leap years, the actual days in the year should be used rather than 365.

In some cases, an analyst may want to know how many days of inventory are on hand at the end of the year rather than the average for the year. In this case, it would be appropriate to use the year-end inventory balance in the computation rather than the average. If the company is growing rapidly or if costs are increasing rapidly, analysts should consider using cost of goods sold just for the fourth quarter in this computation because the cost of goods sold of earlier quarters may not be relevant. Example 7-6 further demonstrates computation of activity ratios using Hong Kong Exchange–listed Lenovo Group Limited.

EXAMPLE 7-6 Computation of Activity Ratios

An analyst would like to evaluate Lenovo Group’s efficiency in collecting its trade accounts receivable during the fiscal year ended 31 March 2010 (FY2009). The analyst gathers the following information from Lenovo’s annual and interim reports:

| US$ in Thousands | |

| Trade receivables as of 31 March 2009 | 482,086 |

| Trade receivables as of 31 March 2010 | 1,021,062 |

| Revenue for year ended 31 March 2010 | 16,604,815 |

Calculate Lenovo’s receivables turnover and number of days of sales outstanding (DSO) for the fiscal year ended 31 March 2010.

Solution.

| Receivables turnover | = Revenue/Average receivables = 16,604,815/ [(1,021,062 + 482,086)/2] = 16,604,815/751,574 = 22.0934 times, or 22.1 rounded |

| DSO | = Number of days in period/Receivables turnover = 365/22.1 = 16.5 days |

On average, it took Lenovo 16.5 days to collect receivables during the fiscal year ended 31 March 2010.

4.2.2. Interpretation of Activity Ratios

In the following section, we further discuss the activity ratios that were defined in Exhibit 7-10.

Inventory turnover and DOH. Inventory turnover lies at the heart of operations for many entities. It indicates the resources tied up in inventory (i.e., the carrying costs) and can, therefore, be used to indicate inventory management effectiveness. A higher inventory turnover ratio implies a shorter period that inventory is held, and thus a lower DOH. In general, inventory turnover and DOH should be benchmarked against industry norms.

A high inventory turnover ratio relative to industry norms might indicate highly effective inventory management. Alternatively, a high inventory turnover ratio (and commensurately low DOH) could possibly indicate the company does not carry adequate inventory, so shortages could potentially hurt revenue. To assess which explanation is more likely, the analyst can compare the company’s revenue growth with that of the industry. Slower growth combined with higher inventory turnover could indicate inadequate inventory levels. Revenue growth at or above the industry’s growth supports the interpretation that the higher turnover reflects greater inventory management efficiency.

A low inventory turnover ratio (and commensurately high DOH) relative to the rest of the industry could be an indicator of slow-moving inventory, perhaps due to technological obsolescence or a change in fashion. Again, comparing the company’s sales growth with the industry can offer insight.

Receivables turnover and DSO. The number of DSO represents the elapsed time between a sale and cash collection, reflecting how fast the company collects cash from customers to whom it offers credit. Although limiting the numerator to sales made on credit in the receivables turnover would be more appropriate, credit sales information is not always available to analysts; therefore, revenue as reported in the income statement is generally used as an approximation.

A relatively high receivables turnover ratio (and commensurately low DSO) might indicate highly efficient credit and collection. Alternatively, a high receivables turnover ratio could indicate that the company’s credit or collection policies are too stringent, suggesting the possibility of sales being lost to competitors offering more lenient terms. A relatively low receivables turnover ratio would typically raise questions about the efficiency of the company’s credit and collections procedures. As with inventory management, comparison of the company’s sales growth relative to the industry can help the analyst assess whether sales are being lost due to stringent credit policies. In addition, comparing the company’s estimates of uncollectible accounts receivable and actual credit losses with past experience and with peer companies can help assess whether low turnover reflects credit management issues. Companies often provide details of receivables aging (how much receivables have been outstanding by age). This can be used along with DSO to understand trends in collection, as demonstrated in Example 7-7.

EXAMPLE 7-7 Evaluation of an Activity Ratio

An analyst has computed the average DSO for Lenovo for fiscal years ended 31 March 2010 and 2009:

| 2010 | 2009 | |

| Days of sales outstanding | 16.5 | 15.2 |

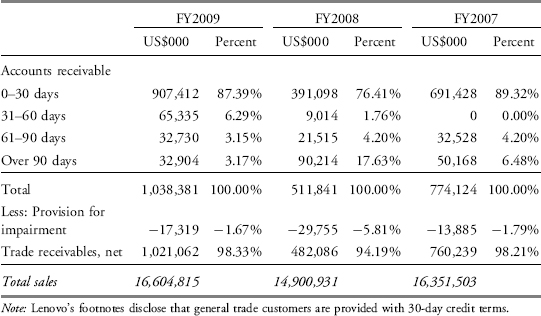

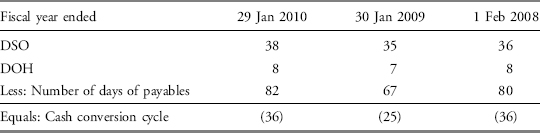

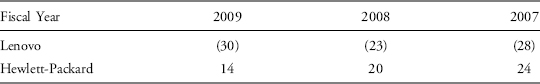

Revenue increased from US$14.901 billion for fiscal year ended 31 March 2009 (FY2008) to US$16.605 billion for fiscal year ended 31 March 2010 (FY2009). The analyst would like to better understand the change in the company’s DSO from FY2008 to FY2009 and whether the increase is indicative of any issues with the customers’ credit quality. The analyst collects accounts receivable aging information from Lenovo’s annual reports and computes the percentage of accounts receivable by days outstanding. This information is presented in Exhibit 7-11.

These data indicate that total accounts receivable more than doubled in FY2009 versus FY2008, while total sales increased by only 11.4 percent. This suggests that, overall, the company has been increasing customer financing to drive its sales growth. The significant increase in accounts receivable in total was the primary reason for the increase in DSO. The percentage of receivables older than 61 days has declined significantly which is generally positive. However, the large increase in 0–30 day receivables may be indicative of aggressive accounting policies or sales practices. Perhaps Lenovo offered incentives to generate a large amount of year-end sales. While the data may suggest that the quality of receivables improved in FY2009 versus FY2008, with a much lower percentage of receivables (and a much lower absolute amount) that are more than 90 days outstanding and, similarly, a lower percentage of estimated uncollectible receivables, this should be investigated further by the analyst.

Payables turn over and the number of days of payables. The number of days of payables reflects the average number of days the company takes to pay its suppliers, and the payables turnover ratio measures how many times per year the company theoretically pays off all its creditors. For purposes of calculating these ratios, an implicit assumption is that the company makes all its purchases using credit. If the amount of purchases is not directly available, it can be computed as cost of goods sold plus ending inventory less beginning inventory. Alternatively, cost of goods sold is sometimes used as an approximation of purchases.

A payables turnover ratio that is high (low days payable) relative to the industry could indicate that the company is not making full use of available credit facilities; alternatively, it could result from a company taking advantage of early payment discounts. An excessively low turnover ratio (high days payable) could indicate trouble making payments on time, or alternatively, exploitation of lenient supplier terms. This is another example where it is useful to look simultaneously at other ratios. If liquidity ratios indicate that the company has sufficient cash and other short-term assets to pay obligations and yet the days payable ratio is relatively high, the analyst would favor the lenient supplier credit and collection policies as an explanation.

Working capital turnover. Working capital is defined as current assets minus current liabilities. Working capital turnover indicates how efficiently the company generates revenue with its working capital. For example, a working capital turnover ratio of 4.0 indicates that the company generates €4 of revenue for every €1 of working capital. A high working capital turnover ratio indicates greater efficiency (i.e., the company is generating a high level of revenues relative to working capital). For some companies, working capital can be near zero or negative, rendering this ratio incapable of being interpreted. The following two ratios are more useful in those circumstances.

Fixed asset turnover. This ratio measures how efficiently the company generates revenues from its investments in fixed assets. Generally, a higher fixed asset turnover ratio indicates more efficient use of fixed assets in generating revenue. A low ratio can indicate inefficiency, a capital-intensive business environment, or a new business not yet operating at full capacity—in which case the analyst will not be able to link the ratio directly to efficiency. In addition, asset turnover can be affected by factors other than a company’s efficiency. The fixed asset turnover ratio would be lower for a company whose assets are newer (and, therefore, less depreciated and so reflected in the financial statements at a higher carrying value) than the ratio for a company with older assets (that are thus more depreciated and so reflected at a lower carrying value). The fixed asset ratio can be erratic because, although revenue may have a steady growth rate, increases in fixed assets may not follow a smooth pattern; so, every year-to-year change in the ratio does not necessarily indicate important changes in the company’s efficiency.

Total asset turnover. The total asset turnover ratio measures the company’s overall ability to generate revenues with a given level of assets. A ratio of 1.20 would indicate that the company is generating €1.20 of revenues for every €1 of average assets. A higher ratio indicates greater efficiency. Because this ratio includes both fixed and current assets, inefficient working capital management can distort overall interpretations. It is therefore helpful to analyze working capital and fixed asset turnover ratios separately.

A low asset turnover ratio can be an indicator of inefficiency or of relative capital intensity of the business. The ratio also reflects strategic decisions by management—for example, the decision whether to use a more labor-intensive (and less capital-intensive) approach to its business or a more capital-intensive (and less labor-intensive) approach.

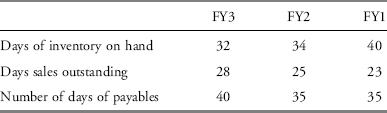

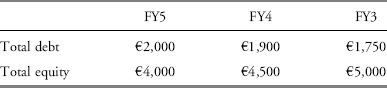

When interpreting activity ratios, the analysts should examine not only the individual ratios but also the collection of relevant ratios to determine the overall efficiency of a company. Example 7-8 demonstrates the evaluation of activity ratios, both narrow (e.g., days of inventory on hand) and broad (e.g., total asset turnover) for a hypothetical manufacturer.

EXAMPLE 7-8 Evaluation of Activity Ratios

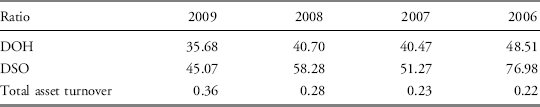

ZZZ Company is a hypothetical manufacturing company. As part of an analysis of management’s operating efficiency, an analyst collects the following activity ratios from a data provider:

These ratios indicate that the company has improved on all three measures of activity over the four-year period. The company appears to be managing its inventory more efficiently, is collecting receivables faster, and is generating a higher level of revenues relative to total assets. The overall trend appears good, but thus far, the analyst has only determined what happened. A more important question is why the ratios improved, because understanding good changes as well as bad ones facilitates judgments about the company’s future performance. To answer this question, the analyst examines company financial reports as well as external information about the industry and economy. In examining the annual report, the analyst notes that in the fourth quarter of 2009, the company experienced an “inventory correction” and that the company recorded an allowance for the decline in market value and obsolescence of inventory of about 15 percent of year-end inventory value (compared with about a 6 percent allowance in the prior year). This reduction in the value of inventory accounts for a large portion of the decline in DOH from 40.70 in 2008 to 35.68 in 2009. Management claims that this inventory obsolescence is a short-term issue; analysts can watch DOH in future interim periods to confirm this assertion. In any event, all else being equal, the analyst would likely expect DOH to return to a level closer to 40 days going forward.

More positive interpretations can be drawn from the total asset turnover. The analyst finds that the company’s revenues increased more than 35 percent while total assets only increased by about 6 percent. Based on external information about the industry and economy, the analyst attributes the increased revenues both to overall growth in the industry and to the company’s increased market share. Management was able to achieve growth in revenues with a comparatively modest increase in assets, leading to an improvement in total asset turnover. Note further that part of the reason for the increase in asset turnover is lower DOH and DSO.

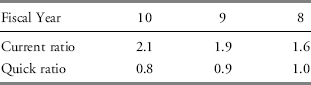

4.3. Liquidity Ratios

Liquidity analysis, which focuses on cash flows, measures a company’s ability to meet its short-term obligations. Liquidity measures how quickly assets are converted into cash. Liquidity ratios also measure the ability to pay off short-term obligations. In day-to-day operations, liquidity management is typically achieved through efficient use of assets. In the medium term, liquidity in the nonfinancial sector is also addressed by managing the structure of liabilities. (See the discussion on financial sector later.)