Principal elements in covering an event

Let us just look at the principal elements of covering a news story from where it happens on location to its transmission from the TV studio.

We will pick a type of story that is of local and possibly national interest. Just suppose the story is the shooting of a police officer during a car chase following an armed robbery.

Camera and sound

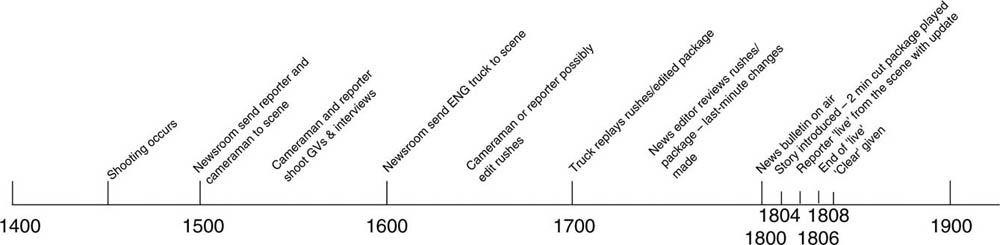

The shooting happened around 2.30 pm, and the TV station newsroom was tipped off shortly after by a phone call from a member of the public at the scene.

Having checked the truth of the story with the police press office, by 3.00 pm the newsroom at the TV station despatched a cameraman (generically applied to both male and female camera operators) and a reporter to the location.

Generally these days, the cameraman is responsible for both shooting the pictures and recording the sound. The reporter finds out all the information on the circumstances of the armed robbery, the car chase and the shooting of the police officer. The cameraman may be shooting ‘GVs’ – general views of the scene and its surroundings onto tape – or interviews between the reporter, police spokesmen and eyewitnesses.

The reporter then will typically record a piece-to-camera (PTC), as shown in the following figure, which is where the reporter stands at a strategic point against a background which sets the scene for the story – perhaps the location where the officer was shot, the police station, or the hospital where the officer has been taken – and recounts the events, speaking and looking directly into the camera.

So by 5.00 pm the cameraman has several tapes (termed ‘rushes’), showing the scene, interviews and the reporter’s PTC. Now, will this material be edited on site to present the story, or will the rushes be sent directly back to the station to be edited ready for the studio to use in the 6.00 pm bulletin?

Editing

The ‘cutting together’ of the pictures and sound to form a ‘cut-piece’ or ‘package’ used to be carried out mostly back at the studio.

Mobile edit vehicles were usually only deployed on the ‘big stories’, or where there was editorial pressure to produce a cut-piece actually in the field. In the latter part of the 1990s, with the increasing use of the compact digital tape formats, the major manufacturers introduced laptop editors.

The laptop editor has both a tape player and a recorder integrated into one unit, with two small TV screens and a control panel. These units, which are slightly larger and heavier than a laptop computer, can be used either by a picture editor, or more commonly nowadays, by the cameraman.

During the 1990s, the pressure on TV organisations to reduce costs led to the introduction of multi-skilling, where technicians, operators and journalists are trained in at least one (and often two) other crafts apart from their primary core skill.

Piece-to-camera (© Telecast Fiber Inc.)

However, the production of a news story is rarely a contiguous serial process – more commonly, several tasks need to be carried out in parallel. For instance, the main package may need to be begun to be edited while the cameraman has to go off and shoot some extra material.

The combination of skills can be quite intriguing, so we can have a cameraman who can record sound and edit tape; a reporter who can also edit tape and/or shoot video and record sound (often referred to as a video journalist or VJ); or a microwave technician who can operate a camera and edit.

So it is often a juggling act to make sure that the right number of people with the right combination of skills available are on location all at the same time.

Getting the story back

There are now three options as to how we get the story back to the studio for transmission on the 6 o’clock news bulletin – it can be:

• taken back in person by the reporter and/or the cameraman

• sent back via motorbike despatch rider

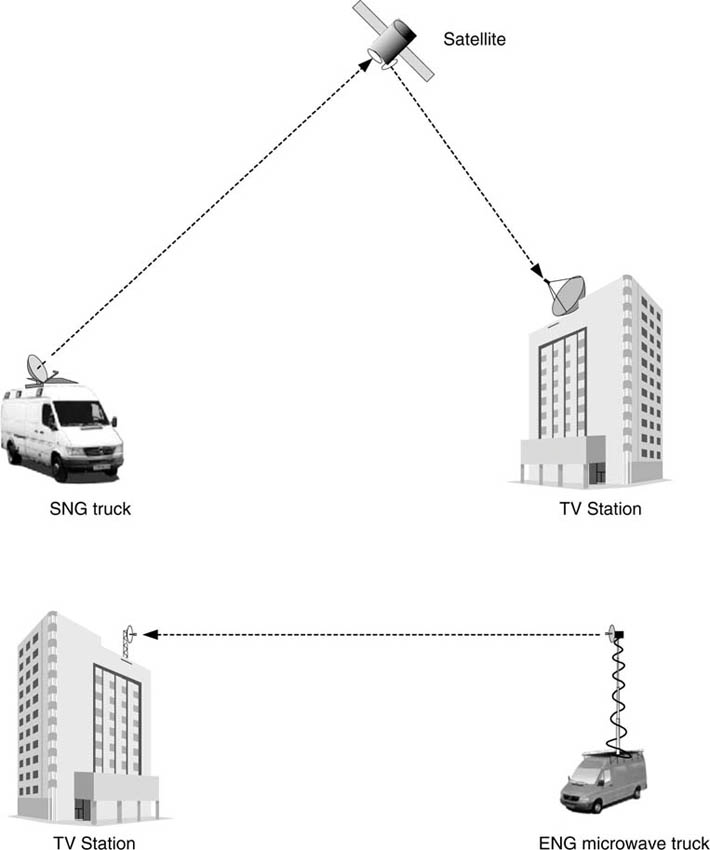

• transmitted from an ENG microwave or SNG microwave truck.

The first two are obvious and so we need not concern ourselves any further. The third option is of course what we are focussed on – and in any case, is the norm nowadays for sending material in this type of situation from location back to the studio.

As it turns out, the newsdesk – realizing the scale of the story once the reporter was on the scene – had despatched a microwave truck down to the location at 4.00 pm. The ENG microwave or SNG truck (for our purposes here it does not matter which) finds a suitable position, and establishes a link back to the studio, with both programme and technical communications in place.

By just gone 5.00 pm, the tape material (rushes or edited package) is replayed from the VTR in the truck back to the studio.

Getting the story back

Going live

The reporter may actually have to do a ‘live’ report back to the studio during the news bulletin, and this is accomplished by connecting the camera to the microwave link truck (along with sound signal from the reporter’s microphone) either via a cable, a fibre optic connection or using a short-range microwave link (more on that later).

From the studio, a ‘feed’ of the studio presenter’s microphone is radioed back to the truck, and fed into an earpiece in the reporter’s ear, so that the studio presenter can ask the reporter questions about the latest on the situation. The reporter will also be provided with a small picture monitor (out of camera shot) so that they can see an ‘off-air’ feed of the bulletin.

This is commonly known as a ‘live two-way’, and what the viewer sees is a presentation of the story, switching between the studio and the location. We will look at this process in more detail in a moment.

Reporter going live

Typical transmission chain

We now have all the elements that form the transmission chain between the location and the studio, enabling either taped or live material to be transmitted.

The camera and microphone capture the pictures and sound. The material is then perhaps edited on site, and then the pictures and sound – whether rushes, edited or ‘live’ – are sent back via the truck (ENG microwave or SNG) to the TV station.

The processes that occur at either end of the chain are the same no matter whether the signals are sent back via terrestrial microwave or via satellite.

Communication with the studio

Being able to keep constantly in touch with both the newsroom and the studio is absolutely vital to a successful transmission. This is true during both the preparation of the story and the actual transmission – particularly if it is to be ‘live’.

Typically the primary communication with the reporter, cameraman and SNG/ENG truck operator is via cellphone and pager. All these key personnel typically carry both a pager and a cellphone.

This might seem somewhat over-cautious, but you should always be aware that cellphones may not work in certain areas for a number of reasons – screening from being within a building, network congestion or just generally poor coverage.

However, pagers, principally because they operate at a much lower frequency, do not suffer from these problems. All the key people on location must be able at least to receive important messages from the TV station, and be able to respond – even if it means stopping at a public payphone to do so!

For live transmissions, another layer of communication (commonly termed ‘comms’) is required – that of the studio control room being able to route communications related to the programme to and from the reporter and crew at the scene.

The ‘live’ crew on location must be able to hear what is going on in both the studio control room (sometimes referred to as the ‘gallery’) and the studio itself.

Talkback

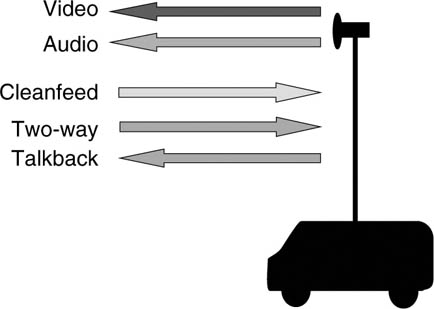

The circuit that carries purely technical conversations is typically known as talkback, and there is ideally both talkback from the studio gallery to the truck, and a reverse talkback from the truck to the studio.

These circuits together are often referred to as a ‘4-wire’, from the property of having a separate send and return circuits enabling simultaneous bidirectional (two-way) conversations.

Typical signals to/from newsgathering vehicle

The circuit which carries the studio programme output is vital, as the reporter must be able to hear the studio presenter to introduce or link into the live piece, listen to cues from the studio control room, and also be able to conduct a two-way dialogue with the studio presenter, which requires the reporter to hear the questions from the studio.

The feed of the studio output to the location is known by a number of names, and the usage vary slightly – cleanfeed, mix-minus, reverse audio, return audio or interrupted fold back (IFB) – so what is actually carried on this the circuit varies slightly according to the term.

Mix-Minus

Cleanfeed, mix-minus, reverse audio and return audio are all terms for what is essentially the same thing – a mix of the studio output without the audio contribution from the remote location. This is important, because if the reporter just listened to the straight output of the studio ‘off-air’, the reporter’s own voice would in effect be heard transmitted to the studio, and then sent back to the location.

The reporter would then hear his/her voice slightly delayed as an echo in their earpiece, which is very off-putting. It is therefore very important that the reporter hears everything being transmitted from the studio ‘less’ (without) his/her own voice – hence the technically accurate term ‘mix-minus’.

IFB is this same mix, but with talkbackfrom the studio gallery superimposed on top. Switched talkback can sometimes be superimposed on the cleanfeed type of circuit as well. The exact configuration varies from broadcaster to broadcaster, and local variations are common.

The reporter, with an earpiece, and the cameraman with either an earpiece or headphones, will be connected to the truck listening to the studio circuit, and this connection will use cable or wireless belt-pack receivers.

These belt-pack receivers pick up the studio comms circuit via a small localized transmitter on the truck. Later on we will see how these circuits can be established – there are a number of ways of doing so.

Back to the story

But for the time being let us just return to our police shooting story outside the hospital where the injured officer is being treated, and look at the process of going live in a little more detail.

The studio has asked for a ‘live’ from the hospital where the police officer is being treated at around 6.05 pm (it is an important story, so it is near the top of the running order of the news bulletin), and it is going to last for around 2 minutes. As we said earlier, the reporter stands in front of the camera, with an earpiece that has a cleanfeed mix from the studio.

The cameraman will also have an earpiece fed with the same as the reporter, as it is just as important that he/she knows exactly what is going on, and these feeds are connected through the truck.

The operator in the truck will also be able to both listen to what is coming from the studio in terms of both cleanfeed and talkback, and also be able to speak to both the cameraman and the reporter via their earpieces.

Let us suppose that the team have already edited and fed a cut-piece back to the studio, which shows the scene of the shooting, and some eyewitness interviews – and this lasts for around 2 minutes.

At 6.04 pm, the studio presenter first introduces the story, summarizing the events so far, and then introduces the cut-piece – this is usually played out from the studio (unless it was only finished close to the ‘live’, and then it may be played out from the truck).

Outside the hospital, the truck operator, the cameraman and the reporter can also hear all of this. It is highly desirable for the truck operator to have got a feed of the ‘off-air’ TV signal, and fed only the off-air video to the camera position where the reporter can see it in his/her field of view on a video monitor without having to avert their eyes obviously from the camera.

As the reporter can see and hear the cut-piece, and because the reporter wrote and recorded the script for the cut-piece earlier, he/she will (hopefully!) know what the concluding sentence is (commonly referred to as the ‘out-words’).

During all of this, the truck operator will have been confirming to the studio that they are ready to ‘go live’, and that the video and audio levels from the truck have been checked and are correct. The truck operator will also make a last minute check with both the cameraman and the reporter that they can hear everything clearly.

At the end of the edited cut-piece (we are now at 6.06 pm), the studio output switches from the tape back to the studio presenter who then introduces the reporter, and the studio ‘cuts’ seamlessly from the studio presenter to the reporter outside the hospital.

At this point, the cleanfeed from the studio will go dead in the reporter’s ear, so that he/she can then speak without hearing themselves back as an annoying echo as we mentioned earlier. As soon as the reporter finishes speaking, their earpiece will spring into life with another question from the studio presenter, and the reporter replies, etc.

This will continue for a period of around 2 minutes, as agreed previously with the studio. As the end time approaches, on the talkback circuit the studio calls out ‘10 seconds’ … ‘5 seconds’ … and hearing this countdown, the reporter smoothly finishes and ‘hands back’ to the studio – it is now 6.08 pm.

As soon as the studio has moved on into the next item in the bulletin, they will call a ‘clear’ on the talkback circuit, and everyone can relax – and I do mean relax! The process of going live is very stressful for everyone – it does not matter how large or small the audience.

There is great emphasis on timing and ‘getting it right’, and the ‘postmortems’ that occur when it does not go right, even in way that the viewer at home would barely notice (if at all), often defies belief – remember no one dies because of television!

It is very important to look smooth and slick in presentation, and the pressure on the reporter, the cameraman and the microwave technician to deliver the live report of a programme may seem out of proportion (after all, no one dies because of TV – but trying telling that to the news editor!). There is a commonly held fear that peoples’ careers are ‘on the line’ in live broadcasting.

On a story like this, which would generally have a high ‘newsworthy’ value, the crew are likely to have to stay at the location to provide updates on the situation.

Particularly with advent of 24-hour news channels – which have a notoriously voracious appetite for news material – the truck and crew could remain on ‘stake-out’ for some considerable time, and have to provide a number of ‘live updates’ through the evening – even if there is nothing to say!

You should now have an overall appreciation of what is involved in undertaking coverage of a news story, and we have looked at the mechanics of what happens at the ‘live end’ in covering this story – and we will come back to this story a little later.

Timeline of the story to air