Operating ENG pneumatic masts

As we saw earlier, ENG trucks inevitably have a pneumatic mast, and this brings us to a hazard that is peculiar to ENG microwave – that of raising the mast. The hazards we have spoken of already are real enough, but of all the equipment we discuss in this book, the most potentially hazardous is not the microwave antenna, or the electrical supply, but the pneumatic mast. The raising of a 40 foot plus pole vertically into the air places a heavy burden of responsibility on the operator.

Overhead hazards

In the United States raising a mast into overhead cables is a too common incident, due to the fact that there are a lot of ENG microwave vans in use, with operators who often have not been trained properly, and working for stations who do not place enough emphasis on safety training. Too much emphasis is on ‘getting the story back’ – at whatever cost.

In addition, the situation is exacerbated because in the United States much of the power distribution in cities is above ground – too much power on poles that should be a lot higher, in the wrong places, and at too high a voltage.

Look up!

The golden rule in operating masts on vans is ‘Look up!’. Always check before you raise the mast that there is nothing above that the mast is likely to become entangled with – and it is a good idea to keep at least 3 m away from any power lines – and 6 m if it is a very high voltage line. In the United Kingdom, lines carrying 240 or 415 V are common on rural roads. Supplies to farms are typically 11 kV. The huge pylons you see marching across the countryside are carrying 132 and 400 kV. The big difference in the United Kingdom is the way our power is distributed, compared to the United States. In UK cities power in urban and metropolitan areas is almost exclusively distributed underground, so it is only in the countryside that it is on poles. In the United Kingdom very high voltage lines are kept well clear of roads, etc., wherever possible.

The second rule is always check the mast is fully down before driving away. Sounds obvious – well, it has happened countless times – in the hurry to get packed up and off to the next story – that the mast gets forgotten about, and the operator drives the vehicle away with a 40 foot pole sticking out of the top of the vehicle.

In the United Kingdom we have been relatively lucky in there having been to date few accidents of this nature – but this should not make us complacent about this issue.

An excellent ENG safety website – www.engsafety.com – lists the known incidents with masts on ENG vehicles in the United States – along with a lot of useful safety information. Many such accidents involved technicians and reporters sustaining serious injuries, including amputation of limbs through severe electrocution burns, and even fatalities. There are on average three reported incidents each year in the United States but it is reckoned that the actual number of incidents is probably around three hundred per annum. As Mark Bell (who runs www.engsafety.com) wisely comments, ‘Accident numbers are only the bad luck, not the actual numbers of incidents. You always have to keep in mind that the only difference between an accident and a catastrophe is luck.’

Anatomy of an ENG accident

The following is an account written by Gary Stigall, an engineer at KFMB-TV in Los Angeles, taken from Mark Bell’s website. It makes sobering reading.

‘At a few minutes before ten on the morning of Monday 22 May 2000, the KFMB-TV assignment editor called over the intercom in an urgent tone, “Could you dial in Telstar Six, One Delta?” The transmissions person was on lunch break. I went into transmissions and hit the screen button that would command the satellite receiver to change channels. What we began to see made us all stop our work.

Unsteady cameras showed us that something terrible had happened to a news van. We heard murmurings about “Adrienne”. The Channel Two photographer was interviewing a mechanic who had witnessed the accident in Hollywood.

I will try to reconstruct the scene in the interest of exploring what happened when a KABC-TV news van microwave dish brushed a power line in Hollywood, burning reporter Adrienne Alpert over 25% of her body. This reconstruction is based on the raw tape and live video I watched from KCBS-TV, from the descriptions of witnesses on the scene, and from friends of people there.

At about 9:40 that Monday morning, photographer Heather MacKenzie and reporter Adrienne Alpert arrived at a Hollywood location on Santa Monica Boulevard where they would join other news crews to report on a story about child car seat safety. They apparently agreed that the location they had first chosen to park was directly under the power lines, so they moved to a location a few feet away, adjoining a shop. However, the location chosen has a pronounced slope downward toward the street, where they had just come from.

Heather must have started the generator and air compressor. The mast is a telescoping air tank, rising when pressurized. The controls were in an industry standard location, just inside the rear doors. When the lever is raised, air flows from storage tank and compressor to the mast. Heather must have opened the doors and began raising the mast. Since the van sat on a slope, the mast was listing from vertical. The photographs taken show that the driver side of the van was within a foot or two of being directly underneath some 34 500 V lines. Above those lines were perhaps a dozen higher voltage lines. This is a busy trunk of electricity.

At some time, Heather went inside the truck where Adrienne sat, and called in to begin transmitting and steering the dish to a relay site. Witnesses, including a couple of mechanics working near where the two had parked, said they began yelling at the two from outside to stop the raising mast. A crew across the street from channel 62 started videotaping the mast as it brushed the wires, and apparently they, too, yelled and waved.

The two women decided to get out of the van’s passenger side doors. Adrienne Alpert stepped out of the van. At that second, the circuit completed from the 34 500 volt line, arcing through the top of the parabolic dish to its inner reflective mesh, to its mount, to the aluminium mast, to the van body, its door handle, from her left hand through her body to her right foot. The van was parked so near the building that the door apparently struck the wall. A nearby drain pipe, perhaps filled with air conditioner condensate, is seen in several after shots with a large char mark where the pipe enters the steel mesh-filled stucco wall. The pavement is wet where the water has been draining near the front of the van. Whether Adrienne stepped on wet ground is not clear. When the door hit the wall, the main explosion apparently occurred.

Whether her windpipes had been burned or her diaphragm had been paralysed, she began having trouble breathing and asked for help. Bystanders wanted to assist, but were not sure whether they were clear of electrocution danger yet. The mast came down from the wires rapidly, the seals having now failed.

The closed circuit feed showed horrible burns on Adrienne’s limbs. As of the date of this writing, she has undergone amputations of the left forearm and right leg below the knee. Heather was not injured.’

This account should make us all pause and reflect – and recite again the mantra ‘No Story Is Worth A Life’.

Unfortunately, in the United States there have been a string of such incidents over the last two decades – many of them are chronicled on www.engsafety.com. It may not only be the operator in the truck who is injured or killed – the cameraman on the end of the cable connected to the truck is just as vulnerable in the event of a mast touching overhead cables.

There are other potential hazards with masts as well. There have been a number of incidents where sections of the mast have ‘launched’ – the tube seals fail and the build-up of pressure fires a section of the mast into the air. This can lead to the frightening prospect of a metal tube hurtling to the ground with a head load of antenna and microwave amplifier in excess of 50 kg.

The pressure of time

Without doubt, however, no matter where the SNG or ENG truck is being driven, the greatest hazard the operator faces is time pressure. Particularly on a breaking story, there is an inherent pressure on the operator to get to the location as quickly as possible to get on air. This pressure may or may not be directly applied – but it is always there. Operators need to exercise considerable self-discipline in order that this pressure does not affect their driving. Stress and fatigue are the two most likely causes of a vehicle accident, both of which are common in working in newsgathering.

Mast safety alarms

There is help at hand in helping detect overhead cables above and beyond your own eyes. There are several products on the market that are designed to detect overhead cables. These essentially detect the electric field radiated from power cables and will both sound an alarm and open the valve on the pneumatic mast, dumping all the air out and so lowering the mast. These devices are effective, and their use is to be encouraged.

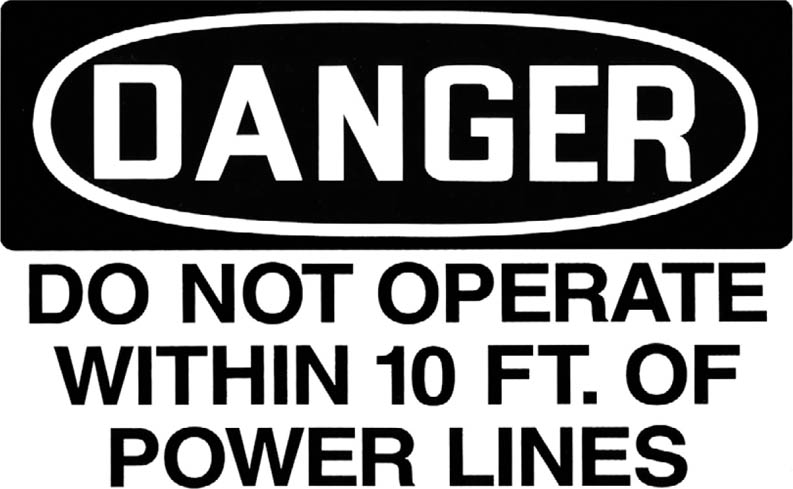

Sign seen in every US ENG truck

Three basic rules:

(1) Check the area above before beginning to raise the mast – power cable within 3 m?-DON’T RAISE THE MAST.

(2) If it is clear, still watch the mast going up – all the way.

(3) Do not forget to watch as you lower the mast – fully – at the end of the assignment.

Follow these rules and the risk of an incident – let alone an accident – will be drastically reduced.