Chapter 5

Perfecting Navigation and Linking Techniques

In This Chapter

- Formulating a category structure

- Building landing pages for silos

- Absolute versus relative linking

- Types of navigation

- Tools to ensure that your navigation is search engine friendly

- Naming links

In this chapter, we talk about how to physically structure your site in the most efficient way possible with siloing. Siloing is the process of categorizing your web pages into subject themes in order to group related content. In this way, you present clear and straightforward subject relevancy that increases your site's perceived expertise to the search engines.

Search engines award keyword rankings to the site that proves that it is least “imperfect” for the relevancy of a subject or theme. That means that the more clearly on-topic a site is for a user’s search query, the more relevant it is, and the more likely it is to appear near the top of search results. Search engines try to dissect a site into distinct subjects that add up to an overall theme that represents a straightforward subject relevancy. If a search engine can clearly understand what you’re talking about, it’s going to consider you more of an expert on the subject and award you a higher rank than the other guy who’s diluted his theme and cluttered his page with junk that’s not relevant to his site. More often than not, a website is a disjointed array of unrelated information with no central theme, and it suffers in search engines for keyword rankings. If you visit a website and you wind up not being exactly sure whether it’s about electric shavers or rubber pants, odds are a search engine isn’t going to know either. Siloing a website helps to clarify your website’s subject relevance.

In this chapter, we discuss how to physically arrange a site for siloing. We go into much more depth on siloing in Book VI, but this chapter gets you started. The first thing we talk about is formulating a linking structure and landing pages: what they are and why they’re important. Next we revisit absolute versus relative linking. Finally, we discuss the types of navigation to use when building a silo, and we finish off with the naming of links.

Formulating a Category Structure

Formulating a category structure is basically grouping your site content to put all your categories together into related directories. In Chapters 1 and 2 of this minibook, we talk about picking major categories and smaller subcategories to go with them. If you’ve already done this, formulating a category structure shouldn’t be so bad.

First, you need to figure out which page is the most important, and then have all your other pages point to it. What page do you think represents your website best? What page do you want your visitors to first see when they visit your website? After you determine your most important page, you can figure out your linking structure. You need to decide what your categories are and what you want to link where so that you can keep from diluting your theme.

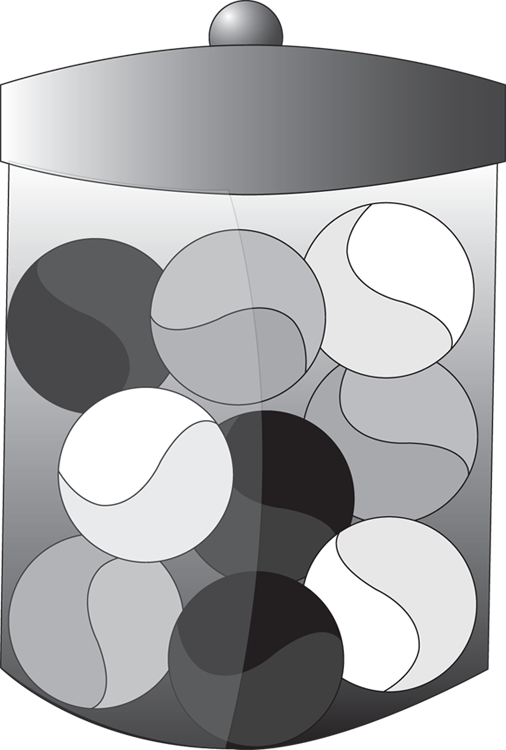

Going back to the jar of marbles analogy we discuss in previous chapters: If you have black, gray, and white marbles all bunched together in a jar, it’s hard to figure out what the “subject” of the jar is. Is it a jar of black marbles with some white and gray mixed in, or a jar of white marbles with black and gray marbles mixed in, or a jar of gray marbles, or something else? Search engines function much the same way when they index a page or a site. Search engines can only decipher the meaning of a page when the subjects are clear and distinct. Take a look at the picture of the jar of marbles in Figure 5-1. How would search engines classify it?

Figure 5-1: A mixed jar of marbles — how would a search engine classify it?

In the jar, you can see black marbles, gray marbles, and white marbles all mixed together with seemingly no order or emphasis. It would be reasonable to assume that search engines would classify the subject as a jar of marbles.

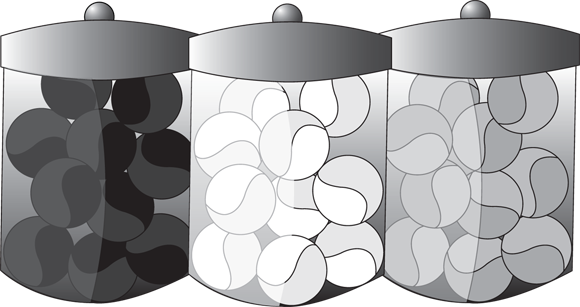

If we then separate each group of colored marbles into separate jars (or websites) as in Figure 5-2, they would be classified as a jar of black marbles, a jar of white marbles, and a jar of gray marbles.

Figure 5-2: In separate jars (or on separate sites), notice how easy it is to categorize by color.

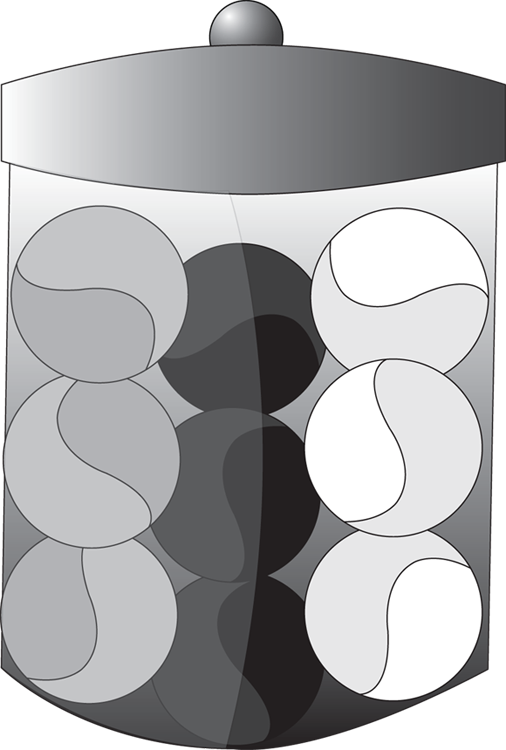

However, if you wanted to put all three marbles (categories) into a single jar (website) as in Figure 5-3, you would create distinct silos or categories within the site that would allow the subject themes to be black marbles, white marbles, gray marbles, and finally the generic term marbles. Most websites never clarify the main subjects they want their site to become relevant for. Instead, they try to be all things to all people.

Figure 5-3: This jar has three distinct themes, or silos.

Categorizing your website makes it easier for a search engine to read and understand the page’s content, and it also helps the user navigate the page.

After you have your categories and subcategories picked out, now it’s time to upload them and set up your site’s directories for easy navigation and siloing. When building a directory structure, it’s important to not go too deep. The directory structure refers to where your files physically exist within the folders on the site. For example, take a look at the following URL of a web page. The full web address identifies the directory where the page physically resides:

http://www.customclassics.com/ford/mustangs/index.html

The URL lets you know where the page is. Notice that there are only two subdirectories under the main domain. Having too many levels of subdirectories does the following things:

- The farther the file is from the root directory, the less important it seems to the search engines.

- Long directory paths make long URLs. Studies have proven that users avoid clicking long URLs on a search results page.

- Long URLs are more apt to cause typos. This could cause broken links within your website (if the webmaster uses absolute linking); also, users could make mistakes typing in your URL.

Therefore, don’t get category happy. Making your directory structure ten directories deep is bad; having five deep is bad too. Having three levels of directories is not as bad, but it’s not great either. We recommend going no more than two directories deep.

For example, our classic car website has only one main category (the car’s make) and two subcategories (model and year). If you have enough content to support multiple sublevels (substantial pages for each category), you could set up the directory structure with two levels. The top-level folders would be labeled with the make; the subfolders would be named by the model. Each page within the subfolder could represent a particular year. So the directory structure would look something like this:

http://www.customclassics.com/ford/delrio/1957.html

http://www.customclassics.com/ford/fairlane/1958.html

http://www.customclassics.com/ford/mustang/1965.html

Note that the directory structure is only two levels deep.

The grouping of content on the site is very significant. One of the ways to think about it is to think of a website as compared with a book: The table of contents describes the overall subject at the beginning of the book, and then the book breaks down into different chapters that support that major subject. The different chapters are the different top-level folders, whereas each chapter (each folder) contains pages (the individual HTML-page files).

The folder or directory is the physical organization of the files (pages) in that root directory. Because a spider cannot physically read the files on the server or in a database (it takes a Content Management System to format pages), you can use several strategies for dynamically organizing data, making even the most ornery Content Management Systems (CMSes) flexible for implementing directory structures. There are two separate ways to understand how a directory structure looks visually — by the URL structure and by folder view:

http://www.classiccars.org/index.shtml

http://www.classiccars.org/Ford/index.shtml

http://www.classiccars.org/Business_Partnerships/Support_Other_Businesses.shtml

http://www.classiccars.org/Business_Partnerships/Value-Added_Partnerships.shtml

http://www.classiccars.org/Chevy/index.shtml

http://www.classiccars.org/Chevy/Comet.shtml

Notice how none of the preceding URLs are longer than one main category and two subjects. Knowing how to group related subject files on your website provides greater primary- and supporting-subject relevancy while also lending a strategy for identifying which sections of your site require greater amounts of content.

Three major subjects define what impact link structure has on implementing silos on your site:

- Internal site linking is how the pages are linked within the span of your site, whether it be linking between major silos or cross-linking related subject pages.

- Outbound, or external, linking represents the offsite links to other sites that are subject-relevant and that provide resources to users that your site can’t offer.

- Backlinks are the format by which other websites link to the pages on your website. You should understand the difference between links from sites that support your theme and links from sites that have no subject matter relevance. The first are good, but the second kind may dilute your subject relevancy.

Selecting Landing Pages

When you’re ready to choose your subject categories, go through and pick what you think would be the most important pages for each category, the ones you want the users to see in the search results and ultimately land on. These are the aptly named landing pages. A landing page can be any or all of three things:

- The first page where users land when clicking the link to your site during their search query

- The page where a user lands after clicking a paid ad

- The page at the top level of a silo

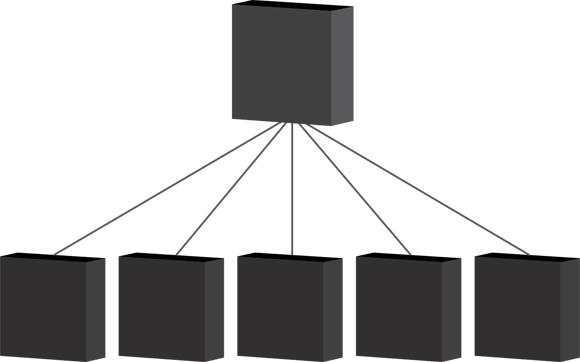

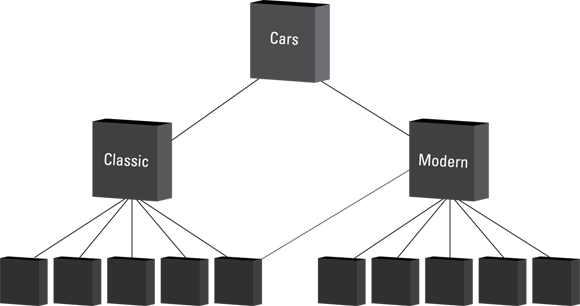

When choosing a page on your site to be a landing page, keep in mind that it should be a big topic with links to a lot of pages that support the topic. If you have less than five pages of support for this page, it’s probably not a landing page. See Figure 5-4 for an example of a landing page with its supporting pages.

Figure 5-4: The landing page is supported by at least five subpages of related content.

Figuring out your landing page depends on what keywords you choose for the page. You want it to be a gateway page to the rest of your site. It should contain the broad keywords you need to draw in the query, and it should funnel users to the other pages with the more specific information they need.

You should be thinking about these questions when deciding which page to use as your landing page: Does the landing page content answer the search query? Does it contain enough information on that page or on its subpages that provide information for a search query? If users don’t find what they’re looking for on your website’s landing page, they’re not going to stick around and explore the rest of your site. Remember, you want people to explore your site, and having a well-crafted silo not only helps your search engine rankings but also enhances the user experience.

One thing to keep in mind is that every page on your website has the potential to be a landing page. One of your subpages could be drawing all the traffic because it contains more relevant information than the actual landing page. This is not a bad thing; it just means one page ended up being a better landing page than the one you thought of. So it’s important to optimize every page just in case. Make sure it reads naturally and is not too forced or obvious; a human user knows when things on a page seem stilted or forced. When linking your pages, you can link as much as you like within a silo (to any related page, whether a landing page or subpage), but if you have to change the subject, always try to link to the landing page of the other subject, not to any subpage. If you must link to a non-theme-related, non-landing page, you need to use a rel="nofollow" parameter on the link.

Linking predominantly to landing pages in the silo is also important. A normal silo looks like Figure 5-5, where the subpages link either to other subpages in the same silo or to the landing page. Notice that they don't link across silos to other subpages in different silos. A good comparison of siloing is to think of it like a pyramid, where the top tier is supported by the level below it, and so on, throughout the pyramid.

Figure 5-5: All the smaller pages support the landing page and link to the next higher-level page.

Absolute versus Relative Linking

In a web page’s HTML code, you have two ways to include a link: relative links and absolute links. An absolute link is a link that contains the whole URL of the file you’re linking to. When it appears in code, it looks the same as when it appears in the browser's address bar:

<a href="http://www.classiccars.com/fords/mustangs/tireoptions.html">Anchor Text</a>

That’s the whole file directory in the link itself. A relative link looks like only part of a full-path URL:

<a href="tireoptions.html"> Anchor Text</a>

<a href="../tireoptions.html"> Anchor Text</a>

When designing your website, we recommend that you don’t use relative links, especially if you’re building your site from the ground up, so you won’t have the added headache of verifying page and media final placement. When you use a relative link, it works only in relation to the next directory up. For example, a link from mustangs/paintoptions.html to <a href="tireoptions.html"> takes you to the intended page only if your site has a mustangs/tireoptions.html for it to link to.

If the pages that were linking out were to get moved somewhere else, the relative link would no longer work because where it linked to would no longer be valid. So if the page was moved from the /mustangs directory to the /mustangconvertible directory, the relative link of <a href="tireoptions,html"> would break because there is no tireoptions.html page in the /mustangconvertible directory.

An absolute link is easier to maintain in situations like this because it’s very clear what you’re linking to. With absolute links, the links still work, even if the pages move.

Use the fully qualified URL (that is, the link target that begins http://domain.com) every time you create a link. Not only is it easier for the engines to understand, but there are also fewer mistakes in the coding of the website, and any mistakes can easily be caught and corrected.

Dealing with Less-than-Ideal Types of Navigation

In Chapter 4 of this minibook, we describe the various types of navigation used in building websites and recommend what is best to use and what is best to avoid. For SEO, it’s important to use text-based navigation because it’s clean, simple, and can be seen by both the search engine and the user.

Unfortunately, you can’t always use text as your navigation system. Sometimes you have a boss who wants the bells and whistles, and you can't convince her that text links work best. Sometimes your CMS won’t allow you to use only text. And sometimes competing in your industry demands those bells and whistles, and users won’t trust your site without them. For example, a movie site may require a more image-based site that includes Flash animation and navigation to showcase movie trailers; a user would think something was terribly wrong with a movie site that’s entirely text-based.

Fear not, for there is a way around these problems in your navigation. You can work around the problems caused by image-, JavaScript-, and Flash-based navigations in order to still rank in the search engines. There is a technical way of working around every problem. It may require a little more work, but if the bells and whistles are something you have to have, the tips in the following sections can help, especially in terms of keeping your silos neat and clean.

Images

As we advise in more depth in Chapter 4 of this minibook, don’t use images for your site navigation unless you have to. Because an image map does not contain any readable text, any text that is contained within the image is not going to be seen by a search engine spider. A spider can only understand the code on the page, not what a human user sees. So any text within the navigation is not counted toward your overall page rank. The only text it is going to read is the Alt attribute text. If you have only one image for the navigation, that’s only going to be one Alt attribute tag. Alt attribute tags do not hold a lot of weight with a search engine because they are easily stuffed with keywords and are spammable.

When you’re building a silo, however, using image-based navigation can be useful. If you need to remove keywords that otherwise dilute your page's target, you can place them in an image, rendering them unseen by a search engine, but still visible to a user.

For example, say you have a page you want to rank in the search engines for research-type search queries. To make this happen, you need to remove any call-to-action keywords such as [purchase] or [buy now] from your web page. Having those keywords on your page enters it into ranking against e-commerce sites, and you run the risk of diluting your page theme and losing the rankings you really want, which are the ones for a research site.

The simple solution is to place all the call-to-action keywords within an image, which renders them invisible to a search engine but still visible to the user. It’s important to keep keywords that do not pertain to your particular silo (remember, they run along a common theme, like a certain model of car or colors of paint) invisible to a search engine.

JavaScript

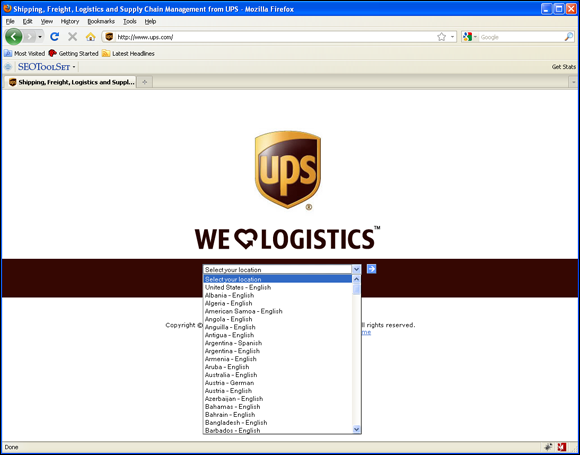

The problem with JavaScript when used in site navigation is that it can confuse the search engine with too much or too little information, especially if the JavaScript navigation is the primary way of getting into a silo. Using JavaScript in the form of a drop-down menu as your site navigation might look pretty and keep navigation convenient, but the search engine reads all this information in each page and attributes it to every single page, as Figure 5-6 shows. Every page on the site would have the unrelated link to the Contact and About pages, which don’t need a global link.

Figure 5-6: The search engine reads all the information in a drop-down menu and attributes it to that page.

If your drop-down menu links to other unrelated pages, the search engine is going to read all the unrelated keywords in that menu and include them when weighing relevancy of that page. For example, your page is about black marbles, but the JavaScript navigation also links to all your pages on white marbles, blue marbles, green marbles, and pink marbles. When every page on the site links to every other page on the site, it dilutes the page content and weakens the silo.

The solution is to externalize the navigation into its own separate JavaScript file that is loaded with JavaScript or in an iFrame. (An iFrame, or inline frame, is an HTML element that lets you embed another HTML document inside the main document.) By externalizing this way, the navigation isn't read as part of the page but rather as its own separate page, so the navigation doesn't dilute your landing pages and silos.

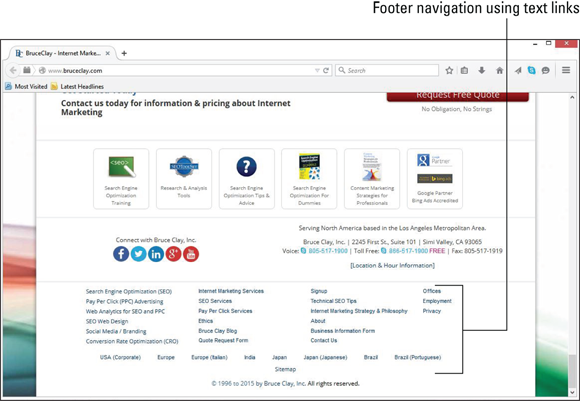

Flash

Flash content is generally not advisable when doing search engine optimization, simply because a search engine can’t read it. There have been some advances with the latest version of Flash that make the text created in Flash readable by spiders, but because it’s so easily spammable, it does not carry as much weight as plain text would. Although some companies’ websites require the use of Flash in order to compete or to look reliable — such as the movie website we mention earlier in this chapter — we recommend not using Flash to create your navigation whenever possible.

The easy way to fix this problem is to have a text-based version of the information at the bottom of the page in the footer that the search engines can read and use in their rankings. People who have Flash turned off can also see the text links on the page, as in Figure 5-7.

Figure 5-7: Repeating Flash content in text in a website‘s footer makes the page accessible for users without Flash and allows search engines to “see” the page.

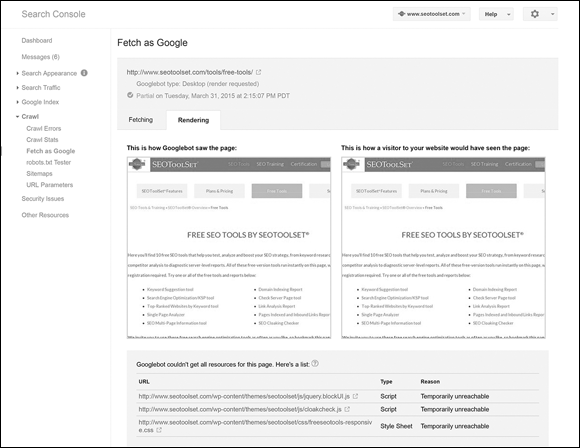

Checking to see what Google sees

If you think you’re dealing with a less-than-ideal type of navigation, a handy tool called Fetch as Google lets you see whether your site’s images, JavaScript, or Flash are obstacles to search engine bots. The Fetch as Google tool simulates what Googlebot does when it arrives at your web page. Found within the Crawl reports in Google Search Console (free for all site owners at www.google.com/webmasters/tools/), you use Fetch and Render to see your site as Google sees it.

Both Google and Bing have multiple crawlers to replicate different browsing experiences. For instance, the search engines have a standard crawler, which acts like a desktop browser, and a mobile crawler, which replicates how a mobile browser interacts with a web page. When you use Fetch as Google, you can choose to see how Googlebot views your page in desktop mode, smartphone mode, or feature phone mode. (A feature phone is a phone that can access the Internet but doesn't have the advanced functionality of a smartphone).

In Figure 5-8, you can see a Fetch as Google report. On the left, you can see “how Googlebot saw the page,” and the image on the right is how a user saw the page on his or her desktop browser. Below that, the report lists any resources on the page that the crawler couldn’t get to, along with a reason.

Figure 5-8: The Fetch as Google report in Google Search Console shows you how Google sees your page and lists any resources on the page that it can’t reach.

When you’re using Fetch as Google to identify problems with your website’s navigation, look for big gaps where your navigation should be in the side-by-side images displayed in the fetch-and-render report. If the image that Googlebot sees and what your visitors see is vastly different, or if Googlebot can’t see something your visitor can see, you may need to give the search engine bots a different way to reach that content on the page. This kind of content gap analysis is a good idea for not only your navigation but also your whole website. Use Fetch as Google to see whether you’re inadvertently blocking chunks of a page from Google’s view.

Naming Links

The naming of links, or writing the anchor text (the words that make up the actual links someone clicks), is one of the most important aspects of siloing. Providing anchor text for a link tells the search engine what the page that’s being linked to is about. If the page content talks about tires, and the anchor text says it’s about tires, and any other links to that page all contain the word tires, that’s a giant neon arrow to the search engine that that particular page is about tires.

When linking to your own content internally, make sure that the anchor text matches the heading of the page you’re linking to. It’s positive reinforcement for the search engines. If the sign that says Pancakes is pointing to a building that advertises pancakes in the window, it’s a pretty safe assumption that the business sells pancakes. That goes double if there are multiple signs pointing to the building saying Pancakes.

Another way of working with anchor text is to vary the actual anchor text. In the case of the signs, it would be something like “Let’s go eat at the pancake place,” “This place makes great pancakes,” and “Let’s go here for pancakes.” You can expand this as well and say the page is about all types of pancakes, so you’d want to link back using synonyms for pancakes like flapjacks, hotcakes, and other types of pancakes. Using synonyms creates good varying anchor text, assuming there were no pages about those synonyms on your site. They all mean the same thing, but the different wording allows for the anchor text to match a greater variety of search queries.

Slight variations in your anchor text wording also sound more natural. That’s the way people talk. It’s important to keep your link names as natural-sounding as possible. Not only is it uncomfortable for users to read things that seem stilted or forced, but the search engines expect to find text that sounds natural, and they may suspect spam otherwise.

Having sites with unrelated subject matter link to your site causes the relevancy to be diluted. The purpose of inbound links is to reinforce subject relevance. This is a major issue for sites that purchase links because the links often originate from a completely irrelevant site.

Having sites with unrelated subject matter link to your site causes the relevancy to be diluted. The purpose of inbound links is to reinforce subject relevance. This is a major issue for sites that purchase links because the links often originate from a completely irrelevant site. Putting your navigation in Flash can be a problem for people who have Flash turned off in their browsers in order to avoid Flash-based ads or to keep their browsers from crashing because of a slow-loading modem. Some people will also have trouble accessing your site from a mobile device (especially from an Apple device, such as an iPhone or iPad) because Flash isn’t supported at all. When these people arrive at your website, they’re not going to be able to see your navigation, and they won’t be able to navigate your site.

Putting your navigation in Flash can be a problem for people who have Flash turned off in their browsers in order to avoid Flash-based ads or to keep their browsers from crashing because of a slow-loading modem. Some people will also have trouble accessing your site from a mobile device (especially from an Apple device, such as an iPhone or iPad) because Flash isn’t supported at all. When these people arrive at your website, they’re not going to be able to see your navigation, and they won’t be able to navigate your site.