Chapter 3

Applying Collected Data

In This Chapter

- Applying best practices to your page construction

- Identifying what’s natural for your competitors

- Sizing up what engagement objects you need

- Building your link equity with a little help from your competitors

- Examining how your competitors organize their content

- Applying your analysis to help with content siloing

Your real competitors online are the sites that show up at the top of the results whenever someone searches for your keywords (words or phrases that people enter as a search query), not necessarily the big name brand in your industry. So if you want your classic car customization business to rank well in the search engines, for example, you can run searches for your main keywords to see who your competition is.

If you just finished the exercises in Chapters 1 and 2 of this minibook, you should have a spreadsheet full of data on your top competitors. Looking at the web pages that the search engines find most relevant for your keywords is a crucial step in your search engine optimization (SEO). Looking at them, you can find out what’s “natural” for your competition. For example, you could find that all the top-ranked web pages have more than 1,000 words of text. You can be pretty sure that if you’re going to rank well for that keyword, you’re going to have to beef up your page’s content to match the competition.

Search engines include many different page factors in their algorithms (in this context, formulas for determining a web page’s relevance to a keyword), which they use to decide the order in which web pages are listed on a search engine results page (SERP). For each ranking factor, it’s impossible to know exactly what the search engine considers to be a “perfect” score. But you can look at the top ranking sites for clues because they’re most consistently ranked for top keyword categories. Of the more than 200 different ranking signals in Google’s algorithm, some are known, but many remain a mystery. For all the known ranking factors, the sites that rank well are the ones that are the “least imperfect” in the search engine’s eyes. So it’s a good idea to try to make yourself equal to them before you try to set yourself apart.

In this chapter, you take the data you’ve gathered on your top competitors and apply it to your own website. In other words, you’re going to figure out how to make yourself equal to and then better than your competition. We talk about the best practices for some of these page elements, which help you make good decisions on how far to go in making yourself equivalent. You also look beyond page elements to other data about your competitors, including their backlinks (incoming links to a web page), their content structure, and what kinds of images, videos, and other types of objects they have on their sites to engage users. All this helps you understand what you need to do to make your site compete in the search engines.

Sizing Up Your Page Construction

It’s time to look at your own website and see how it’s measuring up. Examine your main landing pages, which are the pages best suited for searchers looking for your main keywords. You generally need a minimum of one landing page with at least five secondary or supporting pages/articles dedicated to each of your main keywords so that users searching for those keywords click your link and arrive at a page that delivers just what they’re looking for. You should also have secondary keywords on those pages, but the point is to have focused content that has the main keyword distributed throughout.

Landing page construction

The way your landing pages are put together matters to search engines and helps them determine the relevance of each page. The engines count everything that can be quantified, like the total number of words, how many times your keywords are repeated on the page (prominence), and so forth. It pays to make your page construction line up with what the search engines consider to be optimal for each of these elements as much as possible.

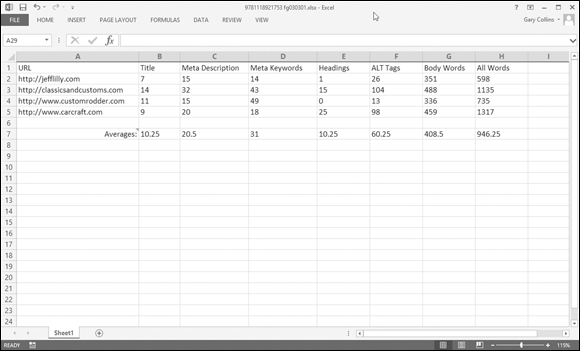

In Chapter 2 of this minibook, we explain how to do research on your top competitors using the Page Analyzer tool’s report (which compiles statistics about a web page such as its keyword density, a percentage indicating the number of times the keyword occurs compared to the total number of words in the page). We recommended that you put your data in a spreadsheet like the one in Figure 3-1, which pulls together stats from four different competitors’ web pages.

Figure 3-1: Spreadsheet showing competitor data from a Single Page Analyzer report.

Notice that there are seven columns of data for each competitor, and the numbers they contain are straight off of the Single Page Analyzer report. Also notice the Averages row at the bottom, which is simply the mean (or average) of each column. It’s a pretty simple way to figure out what’s considered normal (or “natural”) for the top-ranking competitors for your keyword, in the search engines’ eyes. These seven categories represent on-page elements that you can compare to your own web page.

After you study your competitors, it’s time to run your own web pages through the Single Page Analyzer to get your starting figures for comparison. Here’s how to run the Single Page Analyzer:

- Go to

www.seotoolset.com/tools/free-tools/. - In the Single Page Analyzer tool, enter your page’s URL (such as www.yourdomain.com/pageinprogress.html) in the Page URL text box.

- Click the Run Page Analyzer button and wait until the report displays.

After you have your data in hand, you can dig into your analysis. In this list, we cover what we consider to be the SEO best practice for each item and how it lines up with the competitors’ natural usage based on the averages in Figure 3-1. Knowing those two things, you can decide what to do on your own page (these numbers are examples only; your industry will be different):

- Title: The Title tag is a line of HTML you put in the Head, or top, section of a web page’s HTML code:

- Best practice: Six to 12 words (up to approximately 65 characters).

- Competitors’ average: 10.25 words.

- Recommendation: Because the search engines are rewarding these sites with top rankings and those sites’ natural averages fall within best practices, you should make your Title tag ten words in length.

- Meta description: The Meta description is another HTML tag that goes in the Head section of a web page:

- Best practice: Twelve to 24 words (up to 156 characters)

- Competitors’ average: 20.5 words.

- Recommendation: The top-ranking sites seem to be following best practices here, so go ahead and match them by putting 20 or 21 words in your Meta description tag.

- Meta keywords: The Meta keywords tag also goes in the Head section and gives you a place to list all your keywords for the page:

- Best practice: 24 to 48 words in length.

- Competitors’ average: 31 words.

- Recommendation: They’ve done it again, falling within best practice guidelines. You should make your Meta keywords tag about 31 words long.

- Headings: This refers to the number of heading tags on the page (which are h# formatting tags applied to headings and subheadings):

- Best practice: There’s no minimum/maximum guideline for heading tags; however, you should have a single H1 tag at the top of the page for your main headline because search engines look for this. Use H2, H3, and so on throughout the page for subheadings that help break up the text in natural places.

- Competitors’ average: 10.25 tags. However, notice that the competitors don’t agree on this: Their Heading counts are 1, 15, 0, and 25.

- Recommendation: Where you have one or two competitors that are completely out of range of the rest, you shouldn’t try to match the average. Follow the bulk of the sites or best practices instead.

- Alt tags: Alt attributes are alternate text attached to images that briefly describes the image to search engines (and users). In the Single Page Analyzer, the Alt tags figure represents the total number of words included in Alt attributes on the page:

- Best practice: For every image, you should include an Alt attribute (incorporating keywords, if appropriate). The length of the Alt attribute depends on the size of the image but should not exceed 12 words per image for the largest images. (See Book V, Chapter 2 for the mathematical rule of thumb for this.)

- Competitors’ average: 60.25 words.

- Recommendation: There’s a wide disparity between the four sites (26, 104, 13, 98). You should probably follow the best practices rather than the average here.

- Body words: This refers to the number of words in the Body section, which is the part between the beginning and ending Body tags, or the main page content that users see. The count excludes stop words (little words like a, an, but, and others that the search engines disregard):

- Best practice: You should fall within the range of your competitors, but a landing page needs at least 400 to 500 words of readable content as a general rule to establish its relevance to a keyword.

- Competitors’ average: 408.5 words.

- Recommendation: All the competitors’ pages have a similar count, falling within best practices, so this average is probably a sweet spot you’ll want to match or slightly exceed.

- All words: This is the total number of words in the page minus stop words (so it includes the Body section as well as other sections that may or may not be visible to users):

- Best practice: There’s no minimum or maximum guideline here, so match your competitors as long as they’re in keeping with other SEO best practices (such as keeping the HTML code uncluttered, and so on).

- Competitors’ average: 946.25 words.

- Recommendation: Aim to have sufficient text in the Body section and to keep your HTML clean. This number usually takes care of itself.

Want more info on page construction? See Book V, Chapter 3 for additional recommendations on building effective, SEO-friendly page elements.

Content

To make sure that your landing pages have enough focused content to be considered relevant for their main keywords, you want to examine the distribution of keywords on a page. You can do this by looking in the search engine’s cache (stored version of a page). Google’s cached text-only version of a web page is the best way to see how much content the search engines have actually indexed (included in their database of web pages, from which they pull search results).

Pull up Google’s cached text version of a page and then follow these steps:

- Press the Control key and the F key simultaneously. (On a Mac, press Command and F.)

- Type the keyword or keyword phrase and press Enter.

- Select Highlight All and discover an at-a-glance view of the keyword distribution on the page.

This text-only view is what Google sees, and your keywords are highlighted. This view is useful because

- You can find out how much text Google indexed.

- You can see visually how many times you used each keyword.

- You can tell how evenly you distributed the keyword throughout the page.

The Single Page Analyzer report further breaks down how keywords are used on a web page. It identifies all the single- and multiword keyword phrases. It also tells you whether the keywords are used in all the right places (for instance, search engines expect any word used in the Title tag to also appear in the Meta description tag, in the Meta keywords tag, and throughout the page).

For more help using the Single Page Analyzer to optimize your landing pages, see Book V, Chapter 3.

Engagement Objects

Before leaving the subject of page construction, there’s a hot topic you need to know about: engagement objects. Engagement objects are non-text elements such as images, videos, audio, or interactive elements on a web page that help engage users. Not only do they make your page more interesting to a user, but they are also now becoming increasingly important as a search engine ranking factor.

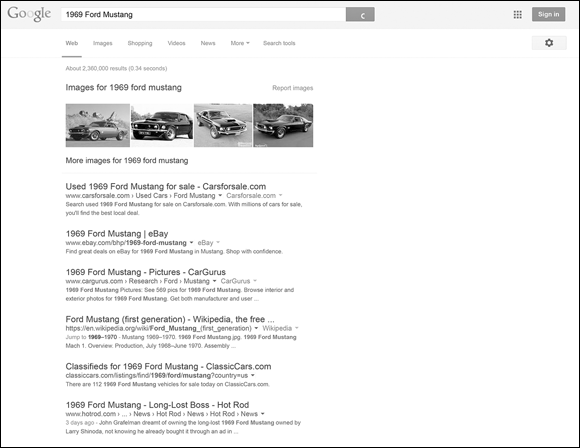

With the rise of blended search (also known as Universal Search in Google), search engine results pages (SERPs) are now able to show a combination of different types of files to a searcher. So a search for [1969 Ford Mustang] can return photos, videos, and so on, in addition to website links, all on the same SERP (as shown in Figure 3-2).

Figure 3-2: Blended search results combine many different types of listings.

The search engines (particularly Google) want to provide the most relevant and engaging results to their users, so having Engagement Objects on your website can actually make you rank higher in search results than your competitors.

Take a look at your top competitors’ web pages as a user would and notice their Engagement Objects. Keep your own website in mind so you can make a list of things you might need to add. Besides getting an overall feel for how these sites engage their users, look to see how extensively they incorporate Engagement Objects such as

- Images: Notice the number of photos, infographics, illustrations, diagrams, charts, and so on. Also pay attention to size. Larger images with good Alt attribute text and good surrounding text can get indexed and actually returned as a search result themselves, so notice whether the competitor has anything like this.

- Video: Video is extremely important these days for getting noticed on the web. The best method is to embed the video right into your landing page and also upload it or a portion of it to a video-sharing site like YouTube. Include a keyword-rich description and a link back to your site, and you’ll probably get traffic as a result. Consider this: YouTube's internal search function now gets more total searches than Yahoo or Bing. Depending on how you look at it, that means YouTube is the second most visited search engine in its own right. Obviously, YouTube’s site search isn’t a true search engine, but you better believe that the traffic is true traffic. If your competitors haven’t been savvy enough to upload videos to YouTube and embed videos on their sites yet, here’s a good way to one-up them. Being where people can find you is critical.

- Audio: Look for embedded audio files within the site, which is another type of element that’s good for user engagement. Audio files are expected on music-industry sites, but other sites might benefit from a creative use of audio, as well. Google can now parse soundtracks and generate text of the words that can be subsequently indexed. This clearly shows that audio is a valid content form.

- Flash: Flash files (SWF) are not recommended, from an SEO point of view. A site built completely in Flash, in particular, can’t be very competitive in searches because it lacks sufficient text content and may be slow to load.

Learning from Your Competitors’ Links

What else can you learn from your competitors? You can find out who’s linking to them.

Besides your page construction, another big factor in your search engine ranking is your link equity, which is the value of all the backlinks coming to your web pages. The search engines consider every link to your web page to be a “vote” for that page. The more votes your page has, the more “expert” your page appears to be. Based on the links pointing to your site, the search engines either increase or decrease how relevant your site is for particular keyword searches. The quality of your backlinks also matters; one testimonial-grade link from an authoritative website in your field is an important endorsement and can be worth more than thousands of links from unrelated and inconsequential sites in terms of your link equity.

You want to have a natural variety of backlinks to your landing pages, from sites with a range of different link equity values themselves. However, it’s good to keep in mind what the gold standard is so that you can recognize a nugget when you see one and go after it. The most ideal backlinks come from a web page that is

- Well-established (that is, an older site that has become trusted)

- An authority within your industry, with lots of backlinks coming to it from related sites, as well as some links out to other authority websites

- Focused on the same subject as your web page, even using some of the same keywords

- Using meaningful anchor text that contains your keywords in the link to your page

Read more about the benefits and risks of link building in Book VI, Chapter 2.

You may have some “ideal” link candidates in mind already: sites that are well-respected and established authorities in your field. It’s very likely, however, that you don’t have nearly enough backlink candidates in mind yet. That’s where looking at your top-ranking competitors comes in handy.

You can look at your competitors’ links primarily to find good backlink candidates for your own site. The top-ranking competitors for your keywords probably have vetted worthwhile links that you could benefit from, too. After all, your competitor deals with the same type of information and customers that you do. If that third-party site finds it useful to link visitors to the competitor’s site, it might find your site equally useful for its visitors to know about.

You can see a list of all the indexed backlinks that a competitor has by running a search engine query on Google. In the regular search box, type the query [link:domain.com], substituting the competing page’s URL for domain.com, and then click the Google Search button. (Don’t include the brackets.)

The results come out in pretty much random order. You can go page by page and read through them, copying the ones that look promising as possible backlink candidates into another document for follow-up. Be picky here: You don’t want any spammy links, and some may simply not be worth the time to pursue.

Suppose your competition has about 50 backlinks. How many do you really need to be competitive? In most cases, reasonably close is sufficient. Focus on developing links in a natural fashion — buying links or devoting huge amounts of time to obtaining reciprocal links is not a good way to gain links. The search engines have ways to detect unnatural links, and having them could cause your website to be penalized by the search engines. (You can read about search engine link penalties in Book I, Chapter 6.)

After you decide which websites you’d like backlinks from, you can begin your link-building campaign. Spend a little time looking at the candidate’s web page. You want to know what it’s about so that you can make sure your own web page has something of value to those users. Another thing you might find is something amiss on the third-party site, like a broken link or a missing image, which you can present to them. This could help you forge a mutually beneficial relationship. Connecting and developing relationships with these brands may eventually lead to natural links, especially if your site offers content (such as articles) that would be useful to their audience. Social media can be an excellent way to make these connections; you learn more about that in Book V, Chapter 7.

Taking Cues from Your Competitors’ Content Structure

You may have a lot of great content on your website, but if it’s jumbled and disorganized, the search engines might not figure out what searches it relates to. This is why you should consider content siloing, which is a way of organizing your website into subject themes by linking related pages together. Content siloing lets you funnel link equity to your landing pages, which reinforces to the search engines how relevant those pages are for the keywords they contain. Linking is so important that it can override the actual content of the page. Siloing is comprised of two parts. One is internal linking and another relates to page and site architecture. Consider a good site map: one that, in a very detailed schematic, outlines the entire structure of a document. Siloing means that all the links on the website follow that outline exactly, without any straying from topic to topic. Literally, the anchor text links do more to inform Google than the content in those pages. Siloing is a big subject. See Book II, Chapter 4 and Book VI, Chapters 1 and 2 for more information.

Looking at the top-ranking competitors’ websites, you can get some clues as to how they organize their content. This can benefit you in two basic ways:

- You can tell how well-organized the competitor’s content is. If the site doesn’t use siloing, your own use of siloing can give you an advantage over the competition.

- You can get ideas for beefing up your own content or for different ways of organizing your site.

Go to a competing web page from a search results page. What can you learn from this landing page about how it fits into the entire site and whether it uses siloing?

First, looking at the navigation structure may give clues. The following navigation example shows how a fairly clear directory structure would be organized by car make (Ford) and then by model (Mustang). This site may have its content siloed:

www.some-car-domain.com/ford/mustang/customize-your-mustang.htm

Now look at this URL, which contains codes and parameters (auto-generated URL characters that carry information to the receiving page about the user) that make it impossible to read:

www.another-car-domain.com/svcse/php?t=37481&_cthew=13%3A2

Obviously, sometimes the URL structure is informative and sometimes it isn’t. Because the URL is another piece of communication that the search engines use to try to understand what a page is about, you want your pages to have meaningful keywords in your URLs. Although very little weight is placed on keywords in the URL, don’t miss that opportunity. Human visitors appreciate the clarity even if the search engines don’t. And if the sites you’re competing against have gobbledygook in their URLs (like the second preceding example), you’ll have another advantage.

Second, you can tell whether a site is well-organized into silos by looking at its internal links. We’re not talking about the main navigation menu so much but about the related hyperlinks on the competitor’s landing page. See whether there are links to pages full of supporting information on the same topic. Then as you click to view those supporting pages, look to see whether they contain links back to the landing page but not to other pages outside that topic. If so, that site is probably siloed.

If they don’t have a siloed linking strategy, you might see

- No links to related pages on the landing page

- The same set of links on every page you look at

- A haphazard assortment of links to various areas of the website, with no clear subject focus

Here are some questions you should answer about your competitors:

- Does the competitor's site organize the main content categories in a clear, readable hierarchical and empirical structure with clear indexable (spiderable) navigation?

- Does the competitor’s site have quality content on each major category section?

- How well does the site link to related articles and site guides?

If the competitor isn’t siloing, and the vast majority of sites are not, that could give you an advantage as you create a theme for your site contents and implement linking within silos.

After you figure out whether the competitor’s site is organized into silos, take a look around and see what tips you can take from it. First of all, you might discover that it's covered something that you missed, like an article about how to preserve the original upholstery of a classic car so that it lasts for decades. Your site visitors probably want to know that, too, so make a note to write a new article to fill that hole.

A well-siloed website might also give you good ideas for organizing content. For instance, your silos might be set up by type of service (body work, reupholstering, complete restoration, and so on), whereas a competitor’s silos might be set up by car make and model. The test of a good silo structure is how much traffic you’re bringing in by being relevant to important keywords. If your structure is bringing in visitors and giving you enough conversions (sales, sign-ups, orders, or whatever action you want people to take on your site), you shouldn’t tear it down.

You might still learn something from another site’s silo structure, however, that you could apply as a horizontal silo within your current structure. A horizontal silo involves linking across silos very deliberately to create a secondary silo structure that can rank for other types of search queries. So if your silo structure is by services, you could consider linking your page titled Reupholstering a Ford Mustang to your pages for Restoring a Ford Mustang and Ford Mustang Body Work, and so on. That would create a set of horizontal silos that might help you rank higher for searches that include [Ford Mustang] as a keyword.

For more help with siloing and overlaying a horizontal silo, check out Book VI, Chapter 2.

Keep in mind that for each item, the best practices just give you a starting point for your analysis. As we mentioned, the top sites are imperfect, so there is room to vary your analysis because your goal is first becoming equal to and then better than your competition. Your market may require certain page elements to be much shorter or longer than the guidelines recommend. Remember that your page construction should make you competitive for your keywords and make judgment calls backed up by real-world results. SEO requires ongoing monitoring and tweaking because the nature of rankings is transitory. Search engine rankings fluctuate, and you have to make tweaks to adapt. Your target number for each element can be changed over time as you get more of a feel for what the search engines consider most relevant.

Keep in mind that for each item, the best practices just give you a starting point for your analysis. As we mentioned, the top sites are imperfect, so there is room to vary your analysis because your goal is first becoming equal to and then better than your competition. Your market may require certain page elements to be much shorter or longer than the guidelines recommend. Remember that your page construction should make you competitive for your keywords and make judgment calls backed up by real-world results. SEO requires ongoing monitoring and tweaking because the nature of rankings is transitory. Search engine rankings fluctuate, and you have to make tweaks to adapt. Your target number for each element can be changed over time as you get more of a feel for what the search engines consider most relevant. If you find that the page has very little textual content that can actually be read by the search engines, your design might be relying too much on nontext elements like images or Flash. (Adobe Flash is a multimedia software program used for building animated and interactive elements for the web.) Although these elements may be good for your users, they’re not very readable to a search engine. In general, landing pages need a lot of text-based content so search engines can figure out what they’re all about.

If you find that the page has very little textual content that can actually be read by the search engines, your design might be relying too much on nontext elements like images or Flash. (Adobe Flash is a multimedia software program used for building animated and interactive elements for the web.) Although these elements may be good for your users, they’re not very readable to a search engine. In general, landing pages need a lot of text-based content so search engines can figure out what they’re all about. Never pay for a link to build your link equity. You can pay for advertising, if you want to attract more visitors or promote your site, but don’t pay for links to increase your link equity. Buying links that look deceptively like regular links can get you in trouble with the search engines, especially Google. When Google detects a paid link, that link typically gets no value. Having too many paid links can trigger an algorithmic penalty (read more about penalties in Book I,

Never pay for a link to build your link equity. You can pay for advertising, if you want to attract more visitors or promote your site, but don’t pay for links to increase your link equity. Buying links that look deceptively like regular links can get you in trouble with the search engines, especially Google. When Google detects a paid link, that link typically gets no value. Having too many paid links can trigger an algorithmic penalty (read more about penalties in Book I,