11. Organizing Analysts

Robert F. Morison and Thomas H. Davenport

One of the most common questions we hear when discussing organizations’ analytical efforts is “How should we best organize our analysts?” It’s a common question arising from a common situation: Analysts and analytics projects are scattered across the organization. That’s how companies get started with analytics—here and there as pockets of interest arise. However, when an organization starts to get serious about analytics, it has to adopt an enterprise perspective to develop analysts effectively and deploy them where they create the greatest business value. Those pockets of analytics need to be coordinated, consolidated, or centralized.

Why Organization Matters

The trend is clearly toward centralization of analysts, and that makes sense for several reasons. If a company wants to differentiate itself in the marketplace through its analytical capabilities, it doesn’t make sense to manage analytics locally. Skilled and experienced analysts are a scarce and high-demand resource. A central agency can deploy them on the most important projects, including cross-functional and enterprise-wide projects that may otherwise be difficult to staff. Centralization also facilitates analyst development because people have more opportunity to connect with and learn from one another. In addition, a central group with a decent population helps with recruiting analysts by demonstrating the organization’s commitment to analytics and providing new hires with a community. Finally, research by Accenture1 shows that analysts in centralized and well-coordinated structures are more engaged and more likely to stay around than their decentralized counterparts.

The second most common situation among organizations we work with is a significant analytics presence in one or two business functions, plus small pockets of analytics across the rest of the organization. The lead functions vary by industry—product development and trading in financial services, engineering and supply chain in manufacturing, marketing in consumer businesses. The challenge is to simultaneously connect the pockets of analytics and spread the wealth of expertise resident in the advanced units. In these cases, full centralization could be unnecessarily disruptive, so the organization needs other mechanisms to coordinate the analyst talent supply.

In the book Analytics at Work, we (along with Jeanne Harris) discuss five common organizational models.2 They’re a useful place to start, but organizing your analysts isn’t as simple as just picking one. There are different organizational circumstances, many variables in play, and many variations on the theme. This chapter decomposes the organizational models for analysts and provides tools for developing and tuning your own model.

General Goals of Organizational Structure

Let’s start with the basics. In addition to their role in employee administration, organizational structures serve two fundamental purposes:

• Deploying people on the important and value-adding work of the enterprise. This is about doing today’s work and maximizing people’s contribution.

• Developing people so that they will have the skills and experience for tomorrow’s work. This is about maintaining the organization’s capability and “health” and maximizing people’s individual and collective potential.

These two goals are interrelated because the most important learning and development occur on the job. But they are in opposition whenever there’s a choice between deploying someone to employ proven skills on an important project and giving the person a new role or “stretch” assignment. Classic hierarchical organizational structures tend to err on the side of keeping people in their “boxes.” Yet analysts will not stay with an organization long unless they have ample variety in their jobs and opportunity to learn.

Organizational design boils down to two big questions:

• What’s the best way to group people to begin with for purposes of both deployment and development?

• What are the necessary and best ways to coordinate across groups? No basic grouping will be perfect in terms of both deployment and development of all staff.

Goals of a Particular Analytics Organization

When debating alternative organizational structures for analytical groups, it’s important to keep in mind the overriding goals for the organization. Typically, the goals of analytical groups and their leadership within companies include the following:

• Supporting business decision-makers with analytical capabilities

• Providing leadership and a “critical mass” home for analytical people and the ability to easily share ideas and collaborate on projects across analysts

• Fostering visibility for analytics throughout the organization and ease in finding help with analytical problems and decisions

• Creating standardized methodological approaches, tools, and processes

• Researching and adopting new analytical practices

• Reducing the cost to deliver analytical outcomes

• Building and monitoring analytical capabilities and expertise

Different priorities for these goals may lead to different organizational models. For example, the goal of supporting business decision-makers with analytics may best be served by locating analysts directly in business units and functions that those decision-makers lead. However, such decentralization may work against the goal of helping analysts easily share ideas and collaborate.

No set of organizational structures and processes is perfect or permanent, so organizations must decide what particular goals are most important at any point in their analytical life cycles. For example, if an organization has had a centralized group of analysts for a while and it has become unresponsive to business unit needs, it may be time to establish stronger ties between analysts and specified business units and leaders. A company with highly localized analytics may need to switch, at least for a while, to a more centralized structure.

Basic Models for Organizing Analysts

Figure 11.1 shows the common organizational models described in Analytics at Work.

Figure 11.1. Five organizational models.

In a centralized model, all analyst groups are part of one corporate organization. Even if located in or primarily assigned to business units or functions, all analysts report to the corporate unit. This obviously makes it easier to deploy analysts on projects with strategic priority, as well as to develop skills and build community. However, especially if the analysts are all housed in the corporate location, it can create distance between analysts and the business. Implementing a centralized model for analytics is easiest where there is successful precedent for operating other functions or managing scarce resources as shared services.

In a consulting model, all analysts are part of one central organization, but instead of being deployed from corporate to business unit projects, the business units “hire” analysts for their analytical projects. This model is more market-driven. Especially important here is the analyst/consultants’ ability to educate and advise their customers on how to utilize analyst services—in other words, to make the market demand smart. This model can be troublesome if enterprise focus and targeting mechanisms are weak because analysts may end up working on whatever business units choose to pay for (or whatever wheel is squeakiest) rather than what delivers the most business value.

In a functional or “best home” model, one major analyst unit reports to the business unit or function that is the primary consumer of analyst services. This analyst unit typically also provides services in a consulting fashion to the rest of the corporation. As already mentioned, many financial services and manufacturing firms have, in effect, a functional model today, with one or two well-established analyst groups in functions such as marketing or risk management. The best home may migrate as analytical applications are completed and the corporation’s analytical orientation changes, typically from operations to marketing.

A center of excellence model is a somewhat less centralized approach that still incorporates some enterprise-level coordination. In this structure, analysts are based primarily in business functions and units, but their activities are coordinated by a small central group. The CoEs typically are responsible for issues such as training, adoption of analytical tools, and facilitating communication among analysts. The CoE builds a community of analysts and can organize or influence their development and their sharing across units. It is most appropriate for large, diverse businesses that have a variety of analytical needs and issues but that still would benefit from central coordination. This is an analytical version of the Gartner-promoted “business intelligence competency center.”

There are many variations on this popular model, depending on the powers of the CoE. Do analysts report to it dotted line? Does it control the staff development agenda and resources? Does it double as a Program Management Office (PMO), with powers to coordinate priorities and resources across business units? Or are the business units solidly in charge of their analysts?

In a decentralized model, analyst groups are associated with business units and functions, and there is likely an analytics group or groups for corporate functions, but there is no corporate reporting or consolidating structure. This model makes it difficult to set enterprise priorities and develop and deploy staff effectively through borrowing and rotation of staff. It is most appropriate in a diversified multibusiness corporation where the businesses have little in common. But even then we feel it makes sense to build a cross-business community of analysts so that they can share experience. As a result, this is the model we are least likely to endorse.

Beneath the surface, each of these models is essentially either centralized or decentralized. The consulting and functional models are variations on centralization. The consulting model has different funding and deployment methods, and the functional model is centralized, just not at corporate. The CoE model is an overlay on a decentralized structure. So are other hybrid models, most commonly a combination of decentralized analyst groups in business units plus a central group at corporate that focuses on cross-functional, cross-organizational, and enterprise-wide initiatives.

These five models have pros and cons and trade-offs in terms of deployment and development and other objectives. Figure 11.2 shows the strengths of each in terms of four specific goals.

Figure 11.2. Strengths of the five organizational models.

Coordination Approaches

One basic structure may be the best general fit, but no model will be best in terms of meeting all goals. Whatever the basic model, there will be a need to coordinate across analyst groups or across different parts of the business that are consuming analyst services. In a sense, all models are hybrids. Even if all analysts work in one centralized corporate unit, the customers for their services are spread across the enterprise. You need coordination mechanisms to manage and meet demand for analytics.

There are a variety of common coordination mechanisms, some of which we’ve already mentioned. These mechanisms can supplement the formal reporting structure for the purposes of enabling groups to plan and work together and developing an enterprise view of priorities and resources. Think of them as ways to supplement and fine-tune a basic centralized or decentralized model, or to compensate for its inherent weaknesses.

• Program management office. This is a formal corporate unit for setting enterprise priorities, coordinating analytics initiatives, influencing resource deployment on key initiatives, and facilitating the borrowing of staff across analytics groups. As mentioned, it may be a function within a CoE. PMOs are especially useful where potential business value is high and resources are scarce and distributed. Under a PMO, the deployment process must be sophisticated to meet the dual needs of project staffing and analyst development.

• Federation. Analyst groups and their associated business units work together on priorities, coordination of initiatives, resource deployment, and analyst development under a set of “guidelines of federation.” The most basic form of federation is a clearly chartered enterprise governance or steering committee. These committees add an immediate enterprise view, but they sometimes lack clout and even commitment.

• Community. Decentralized analysts can be encouraged to share ideas and analytical approaches in a community. Such a community typically would involve occasional meetings, seminars, written communications, or electronic discussions or portals. It may be facilitated by a community organizer, and it typically benefits from a budget.

• Matrix. Analyst groups report both to their associated business units and to a corporate analytics unit, with one line solid and the other dotted. Establishing dotted-line reporting to a central organization injects an imperative to get coordinated, but dotted lines can lose their force over time if they’re not regularly exercised.

• Rotation. Some of the analysts in a centralized model are physically located in and dedicated to business units on a rotational basis. Or an enterprise-wide program facilitates the lending and migration of analysts across decentralized units. The strength and success of rotation programs are easy to gauge. Analysts really do have mobility across the enterprise.

• Assigned customers. Some centralized analytics groups, such as the one at Procter & Gamble, have assigned analysts to work exclusively with particular business units and the leaders of those units. The assignments fall short of a matrixed tie in the organizational structure, but they help ensure that the analytical needs of the units and their leaders are met.

For purposes of deploying analysts on the most important business initiatives, the PMO is the strongest mechanism. For purposes of developing analysts, all the mechanisms can help the cause, and rotation programs have the most profound effect. The coordination mechanisms can be used in combination. Examples include a PMO focused on deployment and a community focused on development, or a federation focused on coordination and a matrix focused on ensuring alignment with business needs.

What Model Fits Your Business?

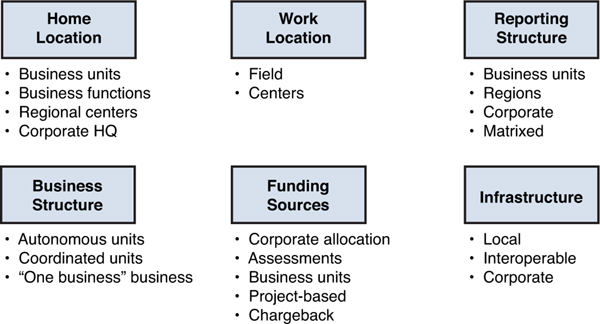

Any basic organizational design for analysts may look good on paper, but it’s got to work in the context of how the business already operates. To evaluate, design, implement, and refine organizational structures, you’ve got to look behind the org chart and consider some basic variables that must work together for any organizational model to succeed. Figure 11.3 shows six key variables,3 described in the following list.

Figure 11.3. Organizational design variables.

• Home location is where analyst groups officially reside for administrative purposes—in business units or functions, regional centers, corporate headquarters, or some mix of these locations. Home base and formal reporting lines have been the dominant variables in organizational design, especially in companies where more headcount has indicated more power. However, in today’s more fluid and collaborative organizations, home location means less and less (especially if coordination mechanisms are effective). Home location is a matter of convenience, with the goals of limiting travel to work locations, accommodating employees’ preferences, and getting enough people in one place regularly to sustain a community.

• Work location is where the work of business analytics is performed, typically a mix of in the field (wherever the business customers of analytical models and services may be) and in regional or corporate analytics centers (where colleagues and support services are readily available). We find it best to locate analytics work, wherever possible, where the corresponding business work is. Make sure that home location and reporting structure don’t erect barriers to analysts’ working close to the business.

• Reporting structure is the formal lines of connection, direction, and administration. Analysts and their groups typically report to local business units, to corporate, or to an intermediate unit (such as business sector or region) if the corporation is so structured. Some reporting structures are a matrix, with analysts reporting solid-line to business units and dotted-line to the corporate analytics organization, or vice versa. Reporting structure may be predetermined if analytics is part of another organization, such as marketing or IT. Make sure that reporting lines are not so rigid as to impede the flexible staffing and development of analysts. Given the advantages of enterprise coordination of analytics, at least a dotted line to corporate makes sense in most organizations.

• Business structure is the shape of the enterprise. Are its business units highly autonomous? Or are they closely coordinated? To what extent do business units already share functions, services, and important-but-scarce resources? Is power concentrated at the regional level? Centralizing analysts may seem the logical thing to do. But it can prove impractical if that flies in the face of a locally autonomous or regionalized business structure.

Centralized analytics groups are a natural match for an integrated “one business” business. If business units are intertwined and must work with and rely on one another regularly, you need a centralized or consulting model, or else a strong federation. If business units are autonomous, with little interconnection, analysts may stay decentralized, but a center of excellence helps in sharing experience and building the analyst community. And if the enterprise relies extensively on business partners to perform major processes, you may need a centralized structure, especially if there is a need or opportunity to coordinate analytics with partners.

• Funding sources are seldom considered in the context of organizational design, even though paralysis is guaranteed if organizational structure and funding sources are at odds. Friction is minimal if funding follows the lines of formal reporting, but matters are seldom that simple because business services such as analytics often have multiple funding sources. These may include funds from corporate, business unit assessments, direct funds from business units, chargeback to business units for analyst time, and project-based funding from the sponsoring business unit or units. The organizational questions are as follows: To what extent does the basic model under consideration align with funding sources? How does funding need to be revised or influenced by coordination mechanisms to support the analytics organization and its work?

Project-based funding is the most market- and demand-driven, but it requires a certain level of maturity among business customers in setting analytics ambitions and priorities, and among analyst groups in advising customers and marketing their services. We recommend that project-based funding (or other funding for services performed) be supplemented by seed funding (to foster innovation) and infrastructure funding (to build capability), usually from corporate.

• Infrastructure includes the configuration and ownership of other essential resources, especially technology and data. This variable is similar to funding sources. Alignment is essential to the success, but the variable is seldom considered in organizational design. Analysts cannot work across business processes and units if local systems and databases, inconsistent tools, and fragmented infrastructure prevent it. And business units cannot incorporate new technologies and techniques for analytical applications if corporate standards prevent it. To capitalize on analytics, the infrastructure must be local-but-interoperable or corporate-but-flexible.

As a practical matter, these six variables are never perfectly aligned with each other, so you’ll have to experiment with and adjust the coordination mechanisms over time. As a common example, if data and technical infrastructure are fragmented, you might phase in an organizational consolidation alongside (or slightly in advance of) the rationalization and consolidation of those resources.

How Bold Can You Be?

How aggressive should you be in your organizational design, especially in terms of consolidating and coordinating existing analyst groups? Sometimes “dropping in” a new centralized organizational structure sends a strong and positive signal. Other times it backfires and causes a backlash because the variables aren’t aligned and the business units aren’t ready. The most sensible path may be an organizational migration—consolidating groups, changing reporting lines, and layering on coordination mechanisms as analytical capability and maturity grow.

Before you proceed with connecting those “pockets of analytics” and consolidating analyst groups, assess how much leverage for consolidation you have (or lack). Consider two variables:

• Analytical orientation is the desire and capability of the various parts of the business to use analytics and manage by fact.

• Enterprise commitment is the desire and capability of the various parts of the business to work together as an enterprise and to compete on analytics.

As shown in Figure 11.4,4 if both factors are high, you can probably bring together analytics groups directly through reporting structure. If analytical orientation is high and enterprise commitment is low, coordination mechanisms can be introduced in turn to build enterprise perspective and commitment. Most companies lead with a CoE to form a community of analysts and then follow with a governance committee to build consensus.

Figure 11.4. Analytical orientation and enterprise commitment.

If enterprise commitment is high but analytical orientation is low, an investment in data and technology infrastructure can enable pilots and basic applications that demonstrate the possibilities. Create pockets of analytics with the intention of later combining them. And if both factors are low, the proponents of analytics need to find and build on local successes and spread the word to generate interest. The organizational issues of analytics are down the road.

Triangulating on Your Model and Coordination Mechanisms

You can zero in on or refine your organizational model for analysts by looking at the problem from a variety of angles and asking the right questions.

Angle 1: Current State

Most enterprises, especially those with low analytical maturity, have “pockets” of analytics in various places—a decentralized and fragmented structure. The first step in coordinating and consolidating is to inventory where analysts are, the kinds of things they’re working on, and how they’re connected and coordinated (if at all). Given the short-term analytical aspirations of the enterprise, what are the pros and cons of the current state? As discussed earlier, how much can you reasonably expect to consolidate and coordinate?

Angle 2: Analytical Maturity

Quickly assess your corporation against the five-stage maturity model (introduced in Competing on Analytics, detailed in Analytics at Work,5 and shown in Figure 11.5). Note the common pattern in organizational evolution:

• Stage 1 and 2 companies tend to be decentralized.

• As ambition grows and becomes specific around Stage 3, the organization centralizes, and the functional model may serve for a time.

• Stages 4 and 5 have strong central organizations.

Figure 11.5. The five-stage maturity model.

The coordination mechanisms similarly evolve:

• At Stages 2 and 3, a center of excellence can build and add coherence to analyst capability.

• At Stage 3 or 4, a program office can focus the deployment of resources.

• At Stage 4 or 5, a formal federation may be necessary if the basic structure still has decentralized groups.

Ask yourself the following questions: What is the likely structure given our company’s level of maturity? If ours needs to be different, why? And what other adjustments do we need to make?

Angle 3: Analytics Strategy/Scenario

Table 11.1 describes seven scenarios6 for how enterprises approach and employ analytics. These different emphases suggest different basic organizational models.

Table 11.1. Ways in Which Enterprises Approach and Employ Analytics

Angle 4: Ambition Check

Consider what the enterprise wants to do with analytics and what it will take to succeed:

• What are the next targets and opportunities? If they are cross-functional, this may call for a more centralized basic model and/or additional coordination mechanisms. If they are process-specific, a temporary “best home” model may suggest itself.

• How urgently does the enterprise need to build analytical capability? More urgency calls for a more centralized model. So does heavy reliance on outside expertise. A center of excellence builds capability less rapidly.

• How important is it to generate and manage demand for analytics across the enterprise? Generating demand may call for “consultative sales” or “seeding” analysts across the enterprise. Managing and focusing demand that’s already there may call for a program office or federation.

Angle 5: Reality Check

What organizational models work in your enterprise? What has been the experience with centralized staff functions and shared services organizations? With corporate consulting groups? Are there precedents for the functional, or “best home,” model? What have been the pros and cons of these models in the past, and what will it take for them to succeed today in the analytics realm?

What has been the experience coordinating across decentralized groups? What has been your specific experience with each of the coordination mechanisms? For example, do your company’s steering and governance committees succeed in enabling coordination, or are they usually limited to information exchange and advisory roles? Which coordination mechanisms can be relied upon? Have any developed a “bad rep?” What needs to be done differently for them to work in the analytics realm?

Finally, revisit the pragmatic constraints imposed by business structure, funding sources, and infrastructure. These variables are not very malleable, especially in the short term.

Analytical Leadership and the Chief Analytics Officer

Another key organizational question is the leadership role for analytics within organizations. Even though few official “Chief Analytics Officers (CAOs)” exist thus far, we expect that more will emerge. The role may not always have that title, but there is a need—at least for each of the three centrally coordinated models described earlier—for someone to lead the analytics organization. The CAO could be either a permanent role or a transitional role for an organization wanting to improve its analytical capabilities.

A Chief Analytics Officer’s tasks could include any or all of the following:

• Mobilizing the needed data, people, and systems to make analytics succeed within an organization

• Working closely with executives to inject analytics into company strategies and important decisions

• Supervising the activities and careers of analytical people

• Consulting with business functions and units on how to take advantage of analytics in their business processes

• Surveying and contracting with external providers of analytical capabilities

One key issue for the CAO role is whether analytical people across the organization should report to it. Although an indirect reporting relationship (as one dimension of a matrixed organization) may be feasible, a CAO without any direct or indirect reports seems unlikely to be effective.

In one insurance firm, for example, the CEO was passionate about the role of analytics and named a CAO as a direct report. But the CAO had only a couple of staff; all other analytics people in the organization did not report to him. The CEO did not want to rock the organizational boat by having such traditional analytical functions in insurance as actuaries and underwriters report to the CAO. As a result, the CAO felt he had no ability to carry out his objectives. He resigned from the role, and the CEO did not replace him.

To Where Should Analytical Functions Report?

There are a variety of different places in the organization to which centralized analytical groups and their CAO leaders can report. Although there is no ideal reporting relationship, each one has its strengths and weaknesses:

• Information technology. Some organizations, such as a leading consumer products firm, have built analytical capabilities within the IT organization or have transferred them there. There are several reasons why this reporting relationship makes sense:

• Analytics are heavily dependent on both data and software, and expertise in both of these is most likely to reside in an IT function.

• The IT function is used to serving a wide variety of organizational functions and business units.

• Analytics are closely aligned with some other typical IT functions, such as business intelligence and data warehousing.

Of course, there are some disadvantages as well. IT organizations are sometimes slow to deliver analytical capabilities and may have a poor reputation as a result. They may also overemphasize the technical components of analytics and not focus sufficiently on business, organization, behavior, skill, and culture-related issues. Finally, IT organizations typically want to produce standardized and common solutions, and this may inhibit one-off analytical projects. In principle, however, there is no reason why IT organizations cannot overcome these problems.

• Strategy. A few analytical groups, including those at a large retailer, report to a corporate strategy organization. This relationship allows analysts to become privy to the organization’s key strategic initiatives and objectives. Another virtue is that strategy groups are often staffed by analytically focused MBAs who may understand and appreciate analytical work, even if they cannot perform it themselves. The possible downsides of this reporting relationship are that strategy groups may be unable to marshal the technical and data resources to make analytical projects succeed, and strategy groups are usually relatively small.

• Shared services. In organizations with a shared administrative services organization, an analytics group can simply be part of that capability. That’s where analytics reside, for example, in an Asia-based telecom company. The primary benefit of such a reporting structure is that analysts can serve anyone in the company—and often charging and resource allocation mechanisms are in place for doing so. The downside is that analytics may be viewed as a low-value, nonstrategic resource like some other shared service functions. With the appropriate mechanisms in place, this problem can surely be avoided.

• Finance. Being numbers-focused, finance organizations have the potential to be a home for business analytics groups. The obvious advantage of this arrangement would be the ability to focus analytics on the issues that matter most to business performance, including enterprise performance management itself. But for some unknown reason, most CFOs have not embraced analytics, and the finance function remains a logical, if uncommon, home for analytical groups. At some firms, however, including Caesar’s Entertainment and Darden Restaurants, the finance function is beginning to play a much stronger role in championing analytical projects and perspectives. Caesar’s has created a shared analytical services group reporting through the CFO.

• Marketing or another specific function. As noted, if an organization’s primary analytical activities are concentrated within marketing or some other specific function, it makes sense to incorporate the analytical group within it. The resulting structure would allow a close focus on the analytics applications and issues in the functional area. Obviously, this would also make it more difficult for analytical initiatives outside those functional areas to be pursued.

Building an Analytical Ecosystem

Most of the foregoing discussion about analytical capabilities has focused on organizing and developing internal analytical capabilities. But a broad set of analytical offerings are made available by a wide variety of external providers as well. These providers include consultants, IT (primarily software) vendors, offshore analytical outsourcers, data providers, and other categories of assistance. Some provide general analytical help across industries, but almost every industry also has specialized analytics and data providers.

The key in constructing an effective analytical ecosystem is not to let it grow at random, but to identify the analytical capabilities the organization needs overall. Then you should decide whether internal or external capabilities are more appropriate to fill a specific need. In general, external capabilities make sense when the need is highly specialized, not likely to be needed frequently, and not critical to the organization’s ongoing analytical capabilities.

A major pharmaceutical firm’s Commercial Analytics group, for example, has a well-developed ecosystem. This is a large group of internal analysts (more than 30), but their abilities are supplemented by outside help when necessary. The group has worked with specialized consultants to analyze physician targeting, for example. The company’s primary prescription data provider also works with it on analytics issues. Software vendors have consulted on analytical methods and techniques. Finally, the group supplements its work with help from an offshore analytics vendor in India.

Developing the Analytical Organization Over Time

A final point is that analytical organization structures should develop and evolve over time. An internal structure and ecosystem that make sense at the beginning of developing analytical capabilities will become obsolete later. For example, it may be reasonable to have a highly decentralized organizational model early on, but most firms create mechanisms for coordination and collaboration around analytics as they mature in their analytical orientations. It may also make sense to “borrow” a number of external resources in a firm’s early stages of analytical maturity before committing to building internal capabilities.

The best way to adapt organizational capabilities to current needs is with a strategy or plan. Admittedly, in the early stages, the organization may not have anyone with the formal authority to even create a plan. However, if it appears that analytics will be key to an organization’s future, it may make sense for a small group of analysts to get together and create a plan from the bottom up.

At a large U.S. bank, for example, the head of the distribution organization (including physical branches, call centers, ATMs, and online channels) had a large number of analysts in her organization. But she believed they weren’t providing the value of which they were capable. She met with the managers of the diverse analytics and reporting groups in her business unit and asked one of them to take the lead in assessing the problem. His work determined that the vast majority of the groups worked on reports rather than more predictive analytics and that virtually no resources were devoted to cross-channel analytics. With this start, the group began to develop a plan to remedy the situation and shift the balance toward predictive analytics and a cross-channel perspective.

Plans should probably be revised every year or so, or when major changes occur in the demand or supply around analytics. There are usually clear signs—if anyone is looking—that the current model has become dysfunctional. It’s a key step in an organization’s analytical development for someone to take responsibility—either informally or formally—for assessing the organization for analytical resources and creating a better model.

No plan or organizational structure is perfect, even for a given time and situation. Every structure, if taken beyond its limits, will become a limitation. The leaders of contemporary organizations need to become conversant with their analytical capabilities and how they are organized. Most importantly, they need to realize when their current organizational approach no longer functions effectively and needs to be restructured.

The Bottom Line

The structure of your analyst organization cannot be slave to the company’s other structures and methods, but it cannot operate in defiance of them, either. If your company is large and complex, odds are your analyst organization will be a hybrid—somewhat decentralized to reflect the shape of the business, but more centralized than the business at large. That means you’ll rely on coordination mechanisms that must simultaneously serve the analytical interests of business units and the enterprise. The ideal may be a strong federation where the parties are collectively motivated to take an enterprise approach to analytics, including prioritizing, funding, and staffing cross-functional and enterprise-wide projects.

Endnotes

1. “Counting on Analytical Talent,” Accenture Institute for High Performance, 2010.

2. Thomas H. Davenport, Jeanne G. Harris, and Robert Morison, Analytics at Work: Smarter Decisions, Better Results, Harvard Business Press, 2010. See pages 104–109.

3. This framework is based on “Building an Analytical Organization,” The Business Analytics Concours and nGenera Corporation, 2008.

4. Ibid.

5. Thomas H. Davenport and Jeanne G. Harris, Competing on Analytics: The New Science of Winning, Harvard Business Press, 2007. See pages 35–40. Thomas H. Davenport, Jeanne G. Harris, and Robert Morison, Analytics at Work: Smarter Decisions, Better Results, Harvard Business Press, 2010. See Appendix, pages 185–188.

6. This framework is based on “Mastering the Technologies of Business Analytics,” The Business Analytics Concours and nGenera Corporation, 2008.