4. Competitor Analysis

Description and Purpose

The purpose of competitor analysis is to provide a comprehensive picture of the strengths and weaknesses of current and potential competitors to identify opportunities and threats for your organization. Competitor analysis has four main objectives:

• Identify competitors’ future plans and strategies.

• Predict competitors’ likely reactions to competitive initiatives.

• Determine the match between a competitor’s strategy and its capabilities.

• Understand a competitor’s weaknesses.

Professor Michael Porter from Harvard University was one of the first strategists to propose a formal and systematic model to gather information about competitors (see Figure 4.1). This model encourages you to use past and current information about competitors to make estimates and predictions. You can estimate the future strategic moves that a competitor may pursue in response to the company’s own strategies. You also can predict the strategies of other companies in the industry or broad changes in the competitive environment external to business strategies. This puts you in a superior position to craft strategies for both attack and defense.

Figure 4.1. The components of competitor analysis.

Source: Adapted from Porter, M.E., Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors (New York: The Free Press, 1980).

The rationale for analyzing your competitors is simple: A superior knowledge of competitors offers a legitimate source of competitive advantage. The essence of competitive advantage is offering uniquely superior customer value in the company’s chosen market. Customer value is defined relative to competitor offerings, making competitor knowledge an intrinsic component of corporate strategy.

Competitor analysis facilitates the objective of achieving superior customer value in three important ways:

• It can reveal strategic weaknesses in competitors that can be exploited.

• Its proactive stance allows the company to anticipate the response of its competitors to its planned strategies, the strategies of other competing companies, and changes in the environment.

• This knowledge of competitive offerings, product or service gaps, and marketing opportunities gives the company enhanced strategic agility and flexibility in its determination of superior options to pursue.

An attacking strategy can be implemented more quickly and with greater impact to capitalize on your strengths and exploit opportunities. Similarly, a defensive strategy can be employed more deftly to counter the threat of competitor companies exploiting your company’s weaknesses.

Clearly, companies practicing systematic and advanced competitor analysis and profiling have a significant advantage. As such, a comprehensive profiling capability is commonly a core competence required for successful business competition.

Strengths

In addition to the advantages just outlined, competitor analysis offers several other related benefits:

• It encourages your company to adopt a confident, aggressive, and proactive position toward competitive strategy and the broader business environment.

• The knowledge provided about competitors allows your company to help shape and define the parameters of strategy rather than react to unexpected competitive sideswipes.

• The inclusive nature of competitor analysis encourages the sharing of insights and perspectives across the company’s functional boundaries. Many opportunities are often uncovered that otherwise would have remained hidden.

• It creates an efficient and effective approach to strategy formulation. The relevant, timely, concise, and visually accessible presentation formats of this technique are an excellent vehicle to communicate strategy.

• It helps the company develop a competitor-conscious culture throughout its workforce. This enables the company to employ its internal networks in support of data and information gathering that can further help it identify opportunities and avoid adverse competitive surprises.

Weaknesses

The primary criticism of competitor analysis relates to the temptation for companies to make it the cornerstone of their competitive strategy. In attempting to become an industry leader, a company will eventually become a follower if it defines leadership too closely in respect to current competitors because of the following factors:

• Comparisons to competitors must always relate to the notion of relative customer value.

• Constantly referencing a company’s strategy to competitors will eventually blind a company to innovative approaches of potential new competitors from outside the periphery of the industry that deliver superior customer value or disrupt the present utilization of business models and strategies. Thus, it is important to keep an eye on potential new competitors from seemingly unrelated sectors and industries.

• The copycat nature of outpacing the competition may prevent any competitive advantage from becoming sustainable. Companies should focus on generating real customer value, not “me-too” imitation, in their search for profitable innovation.

• Most companies fail to thoroughly embed competitor analysis into their ongoing operational, tactical, and strategic development processes. Instead, the majority of companies do competitor analysis on an ad hoc or defensive, fire-fighting, under-resourced basis, thus negating or lessening the benefits that potentially can come from its application.

How to Do It

The competitor analysis process has seven steps:

1. Determine who your competitors are.

2. Determine who your potential competitors may be.

3. Decide what information you need about these competitors.

4. Analyze the gathered information.

5. Present your insights to decision-makers in an appropriate format and in a timely manner.

6. Develop a strategy based on the analysis.

7. Continually monitor competitors, and scan for potential competitors.

Steps 1 and 2: Determine Who Your Competitors Are and Who They May Be in the Future

The first two steps are closely related. Your competitors include companies that serve the same customer base as you. However, what is your customer base? Is it customers of the same product or customers of the same product category? Ultimately, all companies are competitors because they are all trying to attract the same discretionary income. Although this last delineation may sound extreme, it underscores the importance of including potential competitors at the beginning of the analysis. Given the factors of industry changes and value chain erosion, it is important to include potential new competitors at the outset to prevent the analysis from becoming too narrowly focused.

There are two ways to define competitors:

• The traditional method. More adept at identifying current competitors, this method focuses on defining strategic groups within industries. Strategic groups are closely related companies with relatively similar strategies, occupying similar links on the industry’s value chain and sharing similar resource capabilities.

• The less obvious method. This focuses on identifying potential new competitors that are not yet visible. They are developing new ways of delivering customer value on new competitive platforms and often are unaware of the companies they will soon supplant. Companies should focus on customer value and think about which companies their customers view as the major competition. By doing so, they can define potential competitors according to their provision of comparable customer value through different platforms for both products and services. Focus on defining potential competitors based on changing customer tastes and preferences, motivations, product or service deployment, or technological innovation.

Generally, your company’s own customers, sales staff, marketing representatives, and operations managers are your most valuable resources for identifying current and potential competitors, because they interact the most with customers. Other, less-valuable sources may be found online, in industry directories, perusing industry analyst forecasts, applying North American Industry Classification Systems (NAICS) codes or their equivalents, trade association materials, and other secondary information resources.

Step 3: Decide What Information You Need About These Competitors

Start this step with the internal end user of the output of your analysis—the strategic decision-makers within your company. They will be in the best position to itemize exactly what types of competitor information would be most beneficial. To facilitate this objective, focus information gathering on the strategic needs of the decision-makers.

The following list describes the types and categories of information that may be considered during this stage. You can get ideas about useful types and sources of information from surveys and benchmarking studies. However, information needs will be largely industry-specific or even company-specific and will change over time.

Background Information

Name

Location (-s)

Short description

History

Key events

Major transactions

Ownership structure

Products/Services

Number of products/services

Diversity or breadth of product lines

Quality, embedded customer value

Endorsements, certification, and/or awards

Projected new products/services

Current market shares by product and product line

Projected market shares

Segmentation strategies

Branding and image

Probable growth vectors

Advertising/promotions

Market research capability

Customer service emphasis

Four P parameters: product, price, promotion, place

Key customers

Human Resources

Quality and skill of personnel

Turnover rates

Labor costs

Recruiting approaches

Level of training

Flexibility

Union relations

Operations

Manufacturing capacity

Ability to mass-customize

Cycle time, manufacturing agility, and flexibility

Total quality management (TQM) implementation

Process improvement approach

Overhead costs

Lean production methods

Management Profiles

Personality

Background

Motivations, aspirations

Education

Style

Depth of managerial talent

Sociopolitical

Government contacts

Stakeholder reputation

Breadth and depth of portfolio of sociopolitical assets

Political affiliations

Public affairs experience

Nature of government contracts

Connections of board members

Issue and crisis management capacity

Technology

Process technology

Research and development (R&D) expertise

Proprietary technology, patents, copyrights

Life cycle positions

Information and communication infrastructure

Ability to innovate internally

Access to outside expertise through licensing, alliances, joint ventures

Organizational Structure

Nature of hierarchy

Team building

Cross-functionality

Major ownership

Cultural alignment

Competitive Intelligence (CI) Capacity

Evidence of formal CI capacity

Reporting relationships

Profile

CEO and top management level of support

Vulnerability

Integration

Data gathering and analysis assets

Strategy

Positioning

Future plans

Mission, vision, and values

Goals, objectives

Corporate portfolio

Synergies

Resources/capabilities

Core competencies

Customer Value Analysis

Quality attributes

Service attributes

Customer goals and motivations

Customer types and numbers

Net worth (benefits minus costs) of ownership

Financial

Financial statements

Securities filings

Absolute and comparative ratio analysis

Disaggregated ratio analysis

Cash flow analysis

Sustainable growth rate

Stock performance

Costs

If you find you cannot locate the needed data in commonly used secondary sources, you may quickly come to realize that most of the information required for this step already exists inside your company. Salespeople, marketing staff, operations—probably everyone in the company—possess valuable nuggets of competitive information. Figuring prominently in these primary sources of competitive information are your company’s own customers, suppliers and competitor alumni.

Step 4: Organize the Gathered Information into Four Categories

Porter’s four corners framework shown in Figure 4.1 can be used as a guide when analyzing the gathered information:

• Future goals. Determining your competitors’ future goals helps you predict their strategies and plan strategies for your own company. To understand where a competitor is headed, identify its market share, profitability, and organizational performance. Also try to discover what its key spokespeople have said about its future direction. How does it see itself operating in the future?

• Current strategy. Determine which of the three strategies (low cost, differentiation, or focus) your competitor is pursuing. You can identify its current strategy on the basis of what it says and what it does.

Next, identify the strategic implications of each functional area of the competitor’s business. These areas include marketing, sales, operations, administration, manufacturing, R&D, finance, and human resources.

What are your competitor’s stated short-term goals? Start by identifying the differences between its future goals and what it is currently doing. Is there synergy, and do things make sense, or will your competitor require a major shift to achieve its long-term goals? Are its short-term activities in line with its future goals? Remember, in the absence of particular forces for change, you can assume that a company will continue to compete in the future in the same way it has competed in the past.

• Capabilities. Use the information gathered in the current strategy to identify what your competitor is doing and what it has the capacity to do. This is about having the capacity, skills, and resources to actually deliver both its current strategies and future goals. Although a competitor might have announced its strategic intentions, its current capabilities, and its strengths and weaknesses, may not enable it to realize them, thus raising questions about the company’s internal thinking.

• Assumptions. A competitor’s assumptions about itself, the industry, and other rivals yield many useful insights about potentially incorrect ideas or blind spots. Often these blind spots offer competitive opportunities; this is the crux of the analysis. What assumptions does the competitor make about its world, and are these reflected in its strategies, both current and future? Assumptions can be identified by the mismatch between capabilities, current strategies, and future goals. On the other hand, a company that has all three areas in sync may be a formidable competitor. However, all companies make assumptions about the world and the future, and they need to be uncovered.

The critical issue underlying competitor analysis is your understanding of the key assumptions made by the competition. These assumptions may allow you to identify fundamental weaknesses in how they compete and how they see their marketplaces. Answering questions such as Are they satisfied with this position?, What are their plans?, and What are their vulnerabilities? can give you the necessary understanding to take on competitors.

The four analyses are then integrated into a competitor profile. The purpose is to forecast, with reasonable accuracy, how a competitor will respond to various competitive pressures and answer four key questions:

• What is the competitor’s real focus (versus what is claimed or stated)?

• What likely moves or shifts will the competitor make?

• What are the competitor’s blind spots or false assumptions?

• What will be the competitor’s likely response to market initiatives?

The objective is to determine competitors’ attack position to predict moves they may initiate and to determine competitors’ defensive position to forecast how they might react to various competitive pressures.

When you make these determinations, qualitative factors may often outweigh quantitative factors.

Step 5: Present Your Analytical Insights to Decision-Makers in an Appropriate Format and in a Timely Manner

Visual depictions are more effective than written reports. We consider three types of formatting schemes:

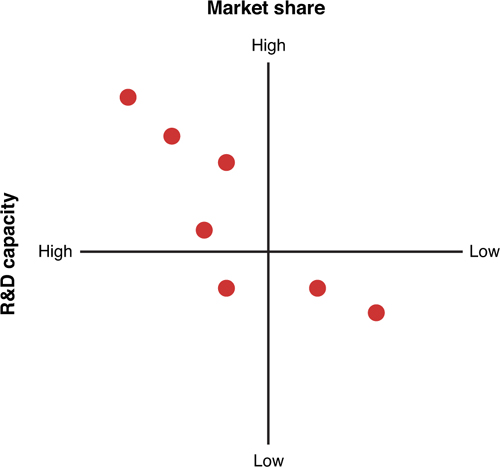

• Comparison grid (see Figure 4.2). Plot competitor positions (performance, capabilities, key success factors) on high/low dependent and independent variable x- and y-axes. Depending on the application, the company’s performance or industry averages are used as the point of reference. Comparison grids provide good snapshots of relative performance across two competitive parameters.

Figure 4.2. Comparison grid.

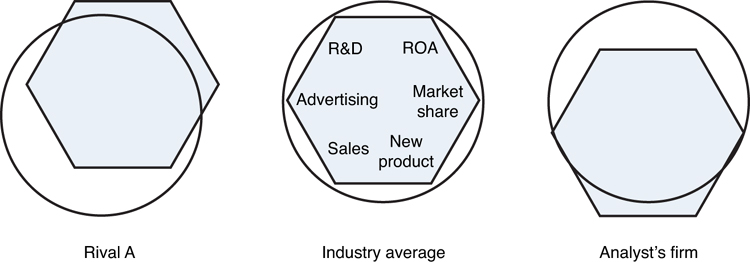

• Radar chart (see Figure 4.3). Easy to comprehend yet dense with information, radar charts are often used to communicate profiling analysis. Radar charts are composed of an underlying circle with several points on the circumference representing industry averages around relative competitive parameters. Superimposed over these circles are geometric shapes representing the performance of the company or competitor being analyzed. The resulting geometric overlay depicts a concise visual of relative performance, whether superior or inferior.

Figure 4.3. Radar charts.

• Visual competitor strength grid (see Table 4.1). Competitor strength grids are a simple yet effective way compare the relative superiority of competitor companies along any number of parameters. By assigning a spectrum of colors or symbols to represent relative competitive inferiority, parity, and superiority, the grid depicts the spectrum of relative competitive advantage among competitors. In Table 4.1,* means best in class, > means above average, < means below average, and • means worst in class.

Table 4.1. Visual Competitor Strength Grid for Six Pizza Delivery Restaurants in Southern Ontario

These charts and similar visual depictions facilitate brainstorming sessions during the strategy development process.

Given the rapidity of environmental and competitive change, competitor intelligence generated by analyses like this have value only if it is received in a timely fashion by the relevant strategic decision-makers. In this respect, timeliness and relevance (that is, perspective) supersede high levels of accuracy (that is, precision) for most competitive analysis purposes.

Step 6: Develop a Strategy Based on the Analysis

At this point, competitor profiles are used to develop strategy around several relevant competitive considerations:

• Determining the probable rules of engagement within that strategic position

• Choosing the arena or scope of engagement—where, how, and against whom your company will compete

• Developing a strategy that leverages your company’s strengths, exploits competitors’ weaknesses, neutralizes competitive threats, and defends against weaknesses

Choose strategies that will force competitors to make costly strategic trade-offs if they decide to impinge on your strategy.

Step 7: Continually Monitor Competitors, and Scan for Potential Competitors

Always assume that competitors are simultaneously performing similar analysis on your company. This is reason enough to engage in continual monitoring. Volatile markets, hyper-competition, industry migration, and decoupled value chains are ample rationale for the continual monitoring of current and potential competitors.

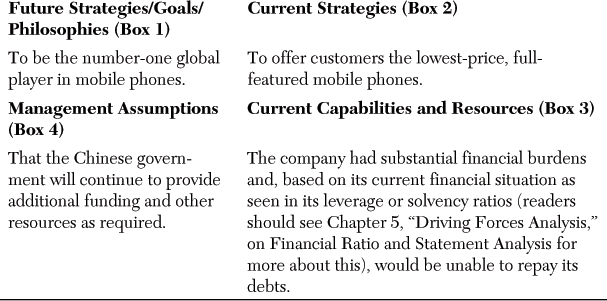

As mentioned throughout this chapter, the key goal of competitor analysis is to understand how competitors might react to your company’s actions and how you can influence competitor behavior to your company’s advantage. Objectives and assumptions are what drive a competitor, and strategy and capabilities are what a competitor is doing or is capable of doing. How can you really understand competitor behavior? Think of competitor analysis (refer to Figure 4.1) as having four distinct boxes:

• Box 1 is future strategies, goals, and philosophies.

• Box 2 is current strategies.

• Box 3 is current capabilities and resources.

• Box 4 is management assumptions.

The analysis occurs with the comparison of information (Step 3) in Boxes 1, 2, and 3.

A company with managers who understand their competitive environment and have a clearly thought-out growth strategy will find that Boxes 1, 2, and 3 match and are cohesive. This suggests that management’s assumptions (Box 4) are minimal and that the company is a formidable competitor.

If Boxes 1, 2, and 3 do not match, you must understand what assumptions are driving management—that is, Box 4. By understanding management’s assumptions, you can understand some key drivers of this competitor’s behavior.

This can best be explained by the following example.

Case Study: Chinese Mobile Phone Market

A competitor analysis was undertaken of a prominent player in the Chinese mobile phone market. Briefly, the following sample information was identified:

The key pieces of information in Boxes 1, 2, and 3 show a mismatch. How can a competitor be a global player offering the lowest-price phones when it cannot repay its debts? A key assumption is operating within the company; it relates to a cultural driver that may no longer be valid. This opens an opportunity for another competitor to offer to buy certain parts of the company, thereby reducing its debt and reliance on the government for additional funding.

However, to clearly understand the impact of the underlying assumptions, you still need to address the four questions:

• What is the competitor’s real focus (versus what is claimed or stated)?

• What likely moves or shifts will the competitor make?

• What are the competitor’s blind spots or false assumptions?

• What will be the competitor’s likely response to market initiatives?

This example provides a brief overview of the technique. However, when collecting information for Boxes 1, 2, and 3, it is important that you cover the breadth and depth of each facet, as explained by the following scenarios:

• Future strategies, goals, and philosophies. A competitor that is focused on reaching short-term financial goals might be unwilling to spend much money in response to a competitive attack. Rather, it might prefer to focus on the products it can defend. On the other hand, a company that has no short-term profitability objectives might be willing to participate in destructive price competition in which neither company earns a profit.

Competitors’ goals commonly include financial issues, growth rate, market share, and technology leadership. Goals may be associated with each hierarchical level of strategy—corporate, business unit, and functional.

The competitor’s organizational structure provides clues about which functions are more important. For example, functions that report directly to the CEO are likely to be given priority over those that report to a senior vice president.

Other aspects of the competitor that indicate its objectives include risk tolerance, management incentives, backgrounds of the executives, composition of the board of directors, legal or contractual restrictions, and any additional corporate-level goals that may influence the competing business unit.

Whether the competitor is meeting its objectives indicates how likely it is to change its strategy.

• Current strategies. The two main indicators of a competitor’s strategy are what it says and what it does. What a competitor says about its strategy is revealed in the following:

• Annual shareholder reports

• Financial reports

• Interviews with analysts

• Statements by managers

• Press releases

However, the stated strategy often differs from what a competitor actually is doing. This is evident in where its cash flow is directed, as in the following actions:

• Hiring activity

• R&D projects

• Capital investments

• Marketing campaigns

• Strategic partnerships or alliances

• Mergers and acquisitions

• Current capabilities and resources. Knowledge of a competitor’s objectives and current strategy is useful in understanding how it might want to respond to a competitive attack. However, its resources and capabilities determine its ability to respond effectively.

A competitor’s capabilities can be analyzed according to its strengths and weaknesses in various functional areas. Analysis can be taken further to evaluate a competitor’s ability to increase its capabilities in certain areas. A financial analysis can also be performed to reveal a company’s sustainable growth rate.

Because the competitive environment is dynamic, you need to know about the competitor’s ability to react swiftly to change. Factors that slow down a company include low cash reserves, large investments in fixed assets, and an organizational structure that hinders quick action.

• Management’s assumptions. The assumptions that a competitor’s management makes about their company and industry help define their moves. For example, if a player in the industry introduces a new type of product that fails, other industry players may assume that there is no market for the product. Such assumptions are not always accurate and, if incorrect, may present opportunities. For example, new entrants might have the opportunity to introduce a product similar to a previously unsuccessful one without retaliation because incumbent companies may not take their threat seriously. Honda was able to enter the U.S. motorcycle market with a small motorcycle because U.S. manufacturers, based on their past experience, assumed that there was no market for small motorcycles.

A competitor’s assumptions may be based on a number of factors:

• Beliefs about its competitive position and other competitors

• Past experience with a product or service

• Regional factors

• Industry trends

• Corporate cultural history

As soon as all four quadrants are completed, you need to turn your attention to the four questions, which are the key to providing succinct commentary on and insights into the competitor being studied.

The outcome of competitor analysis is the development of a response profile of possible moves that a competitor might make. As previously mentioned, this profile includes both potential attacking and defensive moves. The ultimate objective of competitor analysis is an improved ability to predict competitors’ behavior—and even to influence that behavior to a company’s advantage.