10. Scenario Analysis

Description and Purpose

A scenario is a detailed description of what the future may look like. It is based on a set of assumptions that are critical to the evolution of an economy, industry, market, or technology. Scenario analysis is a structured way of developing multiple scenarios that help executives address two common decision-making errors—underprediction and overprediction of change. The objectives of scenario analysis are building a shared baseline for strategic thinking, enhancing flexibility in long-term planning, and providing strategic early warning.

This type of analysis has been in place for decades and is used extensively in a range of industries and by a variety of different organizations (business, not-for-profit, third sector). It can be especially useful for threatened companies or industries that have a strong need to rethink, reengineer, or retool to achieve future competitiveness and profitability. An industry’s level of attractiveness (see Chapter 7, “Five Forces Industry Analysis”) can change as it evolves. Predicting how this evolution will unfold is an uncertain task. When uncertainty levels are high, scenario analysis can be a helpful way for decision-makers and managers to prepare for the future.

Companies facing challenges especially benefit from scenario planning and analysis when the following conditions are present:

• Uncertainty is high relative to managers’ ability to predict or adjust to the future.

• Many costly surprises have occurred in the past.

• The company does not perceive or easily generate new opportunities.

• The quality of strategic thinking among executives is relatively low.

• The industry has undergone or is about to experience significant change.

• The company wants a common planning language and framework without stifling diversity.

• There are strong differences of executive opinion, and several opinions have merit.

• The company’s competitors are successfully using the technique.

Scenario analysis combines quantitative and qualitative analysis that imagines many possible future scenarios of environmental change. It then reduces these scenarios to a manageable number of possibilities, incorporates sensitivity analysis to determine dependent variable relationships, isolates trends and patterns to counteract blind spots in strategic decision-making, and provides a framework for future decisions. By using scenario analysis, you can make decisions in the context of the separate futures that may unfold. The task of creating scenarios compels you to test your future assumptions. By shaping your plans and decisions based on more probable scenarios, you can increase the likelihood that your decisions, plans, and strategies will be sound under various circumstances.

Methods for Generating Scenarios

A scenario is a story about possible futures built on carefully constructed plots. The development of these plots is supported by individuals who have a deep and broad knowledge of the field under investigation. Industry scenarios develop detailed, internally consistent descriptions of what the industry could look like in the future, as shown in Table 10.1. The output of a single scenario is one possible configuration for the industry, whereas a set of scenarios can be used to encompass a wider range of possible futures. The set can then be used to develop and assess potential competitive actions or movements.

Table 10.1. What Scenarios Are and Are Not

The following sections describe the four general types of approaches to developing scenarios.

Quantitative Method

Computer-Generated Econometric Model

This model attempts to integrate a large number of identified interrelationships between trends. If you change one variable, you can analyze the downstream effects along with effects on the initial variable.

Qualitative Methods

Intuitive Method

This method rejects the quantitative approach; instead, it stresses the qualitative variables that are thought to disproportionately affect the future. Fundamental trends are identified and projected into the future to try to construct a surprise-free future. This is done by changing some of the trends to explore other possible future outcomes. Although this intuitive approach is appealingly simple, the high level of abstraction and lack of systematic application make it less practical and therefore difficult to implement.

Delphi Method

In this method, a panel of both internal and external experts are questioned separately (to reduce peer bias) on current and possible future trends in their particular domain of expertise or practice. After several iterations or rounds, the independent results are statistically collated to yield a description of a majority consensus and different opinions. The results are then shared with the panel and organizers. Although somewhat time-consuming because of its iterative nature, the Delphi approach reduces bias and internal politics as it attempts to determine the sequential causal paths of events and issues that will play out in the future.

Cross-Impact Analysis

This approach seeks expert opinion but adds the experts’ estimation of the probability and time of occurrence of future trends or events. The result is a probability distribution of the likelihood and timeframe of future events. This information can be used to determine the impact of removing one trend or event on the remaining trends or events. Cross-impact analysis focuses on the interrelated dependencies between the various identified events, factors, and issues that will impinge on the future.

A mixed scenario analysis is biased toward the qualitative approaches and is a relatively common method employed today. This approach focuses on a qualitative narrative that challenges key assumptions about the future. Initially, a large number of scenarios are developed and are subsequently reduced through either deductive or inductive processes. Through the deductive reduction of the number of factors, the general narrative themes of each scenario are considered, followed by the factors that will be dominant influences in each scenario. Alternatively, inductive reduction involves reducing the factors to a manageable number and then projecting potential future values onto multiple combinations of these factors to derive plausible scenarios.

Both deductive and inductive methods offer benefits but also carry risks. The deductive reduction process allows the analyst to combine many factors into several narratives that describe the future, but it may omit important combinations of factors. Hence, a critical scenario may be missed. Inductive reduction, by first reducing the number of factors, may omit an important variable.

To protect against these blind spots, both approaches generally should be pursued. After you have determined a manageable number of inputs, you can subject the scenarios to more rigorous analysis.

Regardless of which method of scenario analysis is used, five specific scenario types are usually developed:

• The STEEP scenario focuses on events external to the company. Less controllable factors are social, technological, economic, environmental, and political. The important distinction between a STEEP scenario and a traditional STEEP analysis is that the STEEP scenario incorporates factor dependencies to yield new competitive conditions that the STEEP analysis would not readily identify.

• The sensitivity scenario has the opposite focus of a macroenvironmental or STEEP scenario: Internal factors that the company can control are the primary subject of analysis. A common example is the spreadsheet approach used by the finance department.

• The industry scenario focuses on industry-specific issues and trends that are relevant to the company’s business model. It is distinguished from traditional industry analysis in that it analyzes interrelated sequences of trends, events, and issues over time.

• The diversification scenario focuses on industry-specific issues and trends relevant to potential business models the company may pursue in the future. This includes those associated with mergers and acquisitions (M&A) and related, formalized collaboration prospects. It is essentially exploratory in nature and seeks to identify current and future trends in the company’s industry. This type of scenario analysis also envisions the prospects for industry migration.

• The public issue scenario often is used when companies that are disproportionately exposed to specific public issues or stakeholder-related events conduct a public issue scenario. For example, an oil company may choose to center its scenario analysis on energy economics by developing conceivable scenarios of the impact of cartel strength, discovery, delivery disruptions, conflicts, and regulations of its current and future business models.

The most important factor in the success of any scenario-building program is the active involvement of top management. This helps make the seemingly abstract intangibles of scenario analysis more tangible to various members of the management team charged with preparing the company to make decisions about future competition. Another important success factor is the involvement of analysts from diverse backgrounds. In this regard, analysts with strong backgrounds in the liberal arts, humanities, and social sciences can add rich contextual value to the scenario-building process. All else being equal, they will be more attuned to the intangible qualitative factors that often have more bearing on future environments than their more technically or quantitatively oriented colleagues. They are also more likely to act as strategic challengers within the scenario development or analysis process by expressing contrarian viewpoints, thus improving the robustness of the analysis results.

Strengths

Scenarios can be used to help determine the sources of competitive advantage or critical success factors as industries evolve. The consequences of each scenario can be used to predict competitors’ attacking and defensive moves.

The need for internal consistency in scenario analysis forces the analyst to explicitly address the many interrelated sequences and causal paths that may result in conceivable future scenarios. The test of a good scenario is not whether it portrays the future accurately, but whether it enables a company’s decision-makers to learn, adapt, and enrich the ongoing strategic conversation. Through this process of understanding, the company’s managers are much better able to grasp the importance of investing in strategic options as a risk contingency strategy. Scenario analysis is one of the best tools to reduce any corporate blind spots about the external environment.

Scenario analysis also is extremely flexible. The relative degree of quantification/qualification or formal/informal characteristics of the scenario approaches taken can be tailored to the individual company’s culture and capabilities.

Although scenario analysis often incorporates forecasting techniques from raw analytical inputs, it goes one step further. Through narrative stories, scenario analysis starts where traditional forecasting ends. By including informal assessments of possible future environments, scenario analysis embraces relevant variables that are beyond the quantitative purview of established forecasting techniques.

Scenario analysis is a useful technique because of its ability to reduce an overwhelming amount of data and information. It is structured to help management understand future competitive environments. This is liberating from a procedural point of view because it is unnecessary to capture all the details. It also improves a company’s ability to respond nimbly in rapidly changing environments because it does the following:

• Ensures that a company does not focus on catastrophe to the exclusion of opportunity.

• Helps a company allocate resources more prudently.

• Preserves a company’s options.

• Ensures that companies look forward, not backward.

• Allows companies to rehearse the future.

Weaknesses

A potential shortcoming of scenario analysis occurs when companies use it to replace strategy formulation and planning. Scenario analysis allows a company to see the possible consequences of a predetermined strategy, whether it is the company’s current or possible future strategy. As such, this is an analytical technique. Although it may support, decompose, and formalize a particular strategy, it does not, by itself, create new opportunities and strategies.

You must avoid the temptation to select the scenario that best fits the company’s current strengths. You need to resist this natural tendency and remain objective toward the very real possibility of each scenario materializing independent of the company’s current competitive position.

The need to get management to agree on scenarios is critical but not always easy to manage. Because scenarios often include both “soft” and “fuzzy” as well as quantitative and analytical information, getting people to agree on their labels can require much effort and time. Trade-offs must be made when developing simple versus complex scenarios.

Scenarios are also often appealing due to their conceptual simplicity. A difficult trade-off to make in scenario development is between accuracy and direction. However, getting managers and decision-makers to delve deeper into a particular chosen (or base) scenario to understand the level of competitive and financial implications can be difficult, given that most scenarios are constructed at a broad, macro level. Nevertheless, their understanding will grow correspondingly to the deeper the executives dive into them.

How to Do It

Despite its storylike qualities, scenario analysis follows systematic and recognizable phases. The process is highly interactive, intense, and imaginative. You begin by isolating the decision to be made, rigorously challenging the mental maps that shape your perceptions, and hunting and gathering information, often from unorthodox sources. Scenario analysis also requires the analyst to clearly focus the geographic scope of the scenario process at the global, international, nation-state, regional, or more local levels.

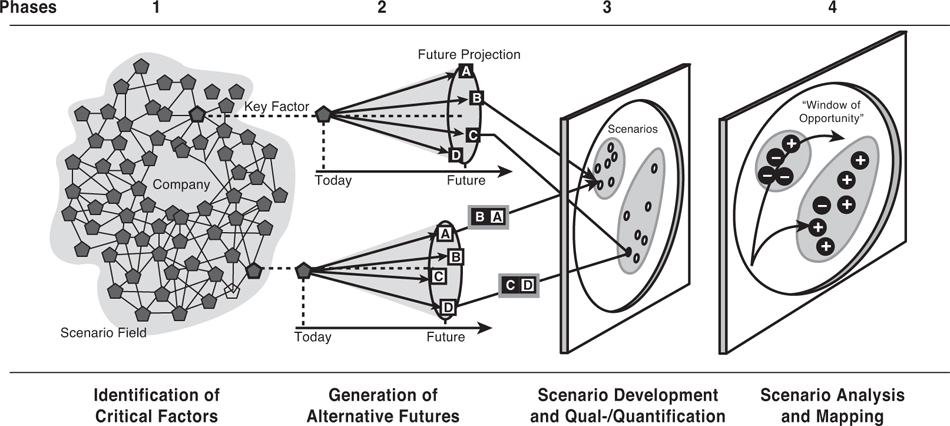

These phases are illustrated in Figure 10.1.

Figure 10.1. Four phases of scenario development.

Source: Adapted from Fink, A., Siebe, A., and Kuhle, J., “How scenarios support strategic early warning processes,” Foresight, 6(3), 2004, 173–185.

Although there is no single correct way to conduct scenario analysis, several practical guidelines have been developed from collective experience with this approach. The process we describe next for developing scenarios is the one promoted most notably by Schoemaker:1

1. Define the scope of the analysis. Set the timeframe and scope of the analysis in terms of products, markets, customer groups, technologies, or geographic areas. The timeframe depends on several factors, including industry or product life cycles, political elections, competitors’ planning horizons, rate of technological change, and economic cycles. Once the appropriate timeframe has been determined, ask what knowledge would be the most valuable to your company at that point in time.

2. Identify the major stakeholders. Stakeholders are individuals or groups who have a key interest or stake in the outcome of the target being analyzed. Who will have an interest in the development of important issues in the future? Who will be affected by these people, and who will affect them? Identify the stakeholders’ current roles, interests, and power positions, and then assess how they have changed over time. This is done through a rigorous stakeholder analysis, an analytical method we describe more comprehensively in another of our books.2

3. Identify the basic trends. What industry and STEEP trends are likely to affect the issues you identified in the first step? Briefly explain each trend, including how (positively, negatively, or neutrally) and why it influences your company. Trends that show disagreement over their likely continuation are dealt with in the following step.

4. Identify the uncertainties. What outcomes and events are uncertain (probabilistic) or will significantly affect the issues you are concerned about? For each uncertainty, determine possible outcomes (that is, legislation passed or defeated, or technology developed or not developed). Also attempt to determine whether relationships exist among these uncertainties, and rule out combinations that are implausible (for example, steadily increasing government and private debt and deficits along with steadily declining interest rates).

5. Construct initial scenario themes. You can take several approaches. You can select the top two uncertainties and evaluate them. You can cluster various strings of possible outcomes around high versus low continuity, degree of preparedness, turmoil, and so on. Or you can identify extreme worlds by putting all positive elements into one scenario and all negative elements into another.

6. Check for consistency and plausibility. Assess the following: Are the trends compatible within the chosen timeframe? If not, remove trends that do not fit. Next, do the scenarios combine outcomes of uncertainties that indeed fit together? If not, eliminate that scenario. Finally, are the major stakeholders placed in positions they do not like and can change? If so, your scenario will evolve into another one.

7. Develop learning scenarios. Some general themes should have emerged during the previous steps. Your goal is to identify themes that are strategically relevant and then organize the possible trends and outcomes around these themes. Although the trends appear in each scenario, they should be given more or less weight or attention in different scenarios as appropriate.

8. Identify the research needs. You might need to delve more deeply into your blind spots and improve your understanding of uncertainties and trends. For example, consider whether you really understand how stakeholders are likely to behave in a particular scenario.

9. Develop quantitative models. Reexamine the internal consistencies of the scenarios, and assess whether certain interactions need to be formalized via a quantitative model. The models can help quantify the consequences of various scenarios and keep managers from straying toward implausible scenarios.

10. Evolve toward decision scenarios. Iteratively converge toward scenarios that you will eventually use to test your strategies and generate innovative ideas. Ask yourself whether the scenarios address the real issues facing your company and whether they will spur the creativity and appreciation of your company’s decision-makers.

These steps should ideally culminate in three or four carefully constructed scenario plots. If the scenarios are to function as learning tools, the lessons they teach must be based on issues that are critical to the decision’s success. Only a few scenarios can be fully developed and remembered, and each should represent a plausible alternative future, not a best case, worst case, and most likely continuum. Once the scenarios have been fleshed out and made into a narrative, the team identifies their implications and the leading indicators to be monitored on an ongoing basis.

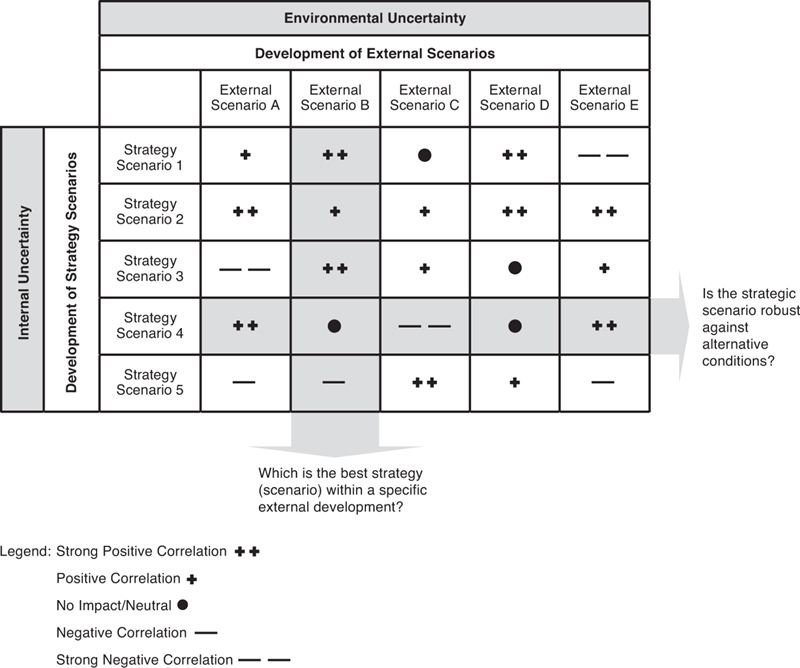

This can also be represented in a scenario matrix, as shown in Figure 10.2.

Figure 10.2. Scenario matrix.

Source: Adapted from Fink, A., Siebe, A., and Kuhle, J., “How scenarios support strategic early warning processes,” Foresight, 6(3), 2004, 173–185.

After you’ve chosen the number of scenario plots, you must determine the company’s strategic intent. It is here that scenario analysis ends and strategic decision-making begins. Essentially, the company has three options when dealing with future uncertainty:

• Shape the future. The most intense stance is for the company to plan to be a shape-shifter by defining the competitive parameters of future scenario(s) by betting on future trends (such as technological discontinuities or the erosion of mobility barriers).

• Adapt to the future. This benchmarking approach puts the company in a position of operational excellence to capitalize on trends as soon as they develop.

• Strategic options. This is a more conservative, proactive strategy that invests the minimal amount necessary to acquire or otherwise purchase strategic options, while avoiding overt vulnerability.

These three strategic opportunities offer different levels of risk and hence different levels of potential reward.

Unlike traditional forecasting or market research, scenarios present alternative images instead of extrapolating current trends from the present. Scenarios also embrace qualitative perspectives and the potential for sharp discontinuities that econometric and other stable-state quantitative models exclude. Consequently, creating scenarios requires managers to question their broadest assumptions about how the world works so that they can anticipate decisions that might otherwise be missed or denied. Within the company, scenarios provide a common vocabulary and an effective basis for communicating complicated conditions and options.

Good scenarios are plausible and can be surprising, and they should have the power to break old stereotypes. By using scenarios, you and your participating colleagues are rehearsing the future. By recognizing the warning signs and drama that are unfolding, you can avoid surprises and adapt and act effectively. Decisions that have been tested against a range of possible futures are more likely to stand the test of time and produce robust and resilient plans of action. Ultimately, the end result of scenario analysis is not a more accurate picture of tomorrow, but better decisions today.

Case Study: Scenarios for Traditional and Emerging Forest Products Enterprises

These scenarios were identified by Don Roberts (Vice Chairman of CIBC Wholesale Banking) and Dr. Sten Nillson (a researcher at the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis [IIASA]), two well-known experts in the international forest sector community. The main scenario inputs are energy, carbon, and fiber prices.3 The scenarios were given the following names: The World Continues Its Course, Repeated Economic Meltdown, Skyrocketing Energy Prices, and Emerging Carbon Economy. These are described in the following sections.

Scenario 1: The World Continues Its Course

The forest products industry, like many other industries, suffered dramatically during the global recession beginning in 2006. The growth rate in both developing and developed countries had stagnated or even reversed. Housing starts in large, established markets such as the U.S. and Canada had reached historically low levels by 2009. The demand for building materials and lumber products had been severely depressed, particularly compared to the first seven years of the decade.

This scenario sees the beginning of indicators suggesting that the recovery had begun by 2009–10. Recovered industrial activity, the stabilization of housing markets and particularly the financial institutions and regulations supporting their financing, and a consumer desire to satisfy pent-up demand for home improvement could all be expected to push demand for forest products and prices back to near pre-crisis levels. As such, demand levels and prices would return to similar levels experienced pre-crisis, and the world would continue its course.

Scenario 2: Repeated Economic Meltdown

Since 2007, the U.S. has suffered one of the worst financial meltdowns in its history, rivaling only the Great Depression in terms of magnitude, if not duration. Easy credit and debt-financed consumption fueled a construction and housing boom that led global investors to flock to U.S. financial markets where returns looked attractive. These markets took a significant hit when borrowers began to default on their financial obligations, housing prices declined dramatically in many major housing markets, and financial institutions experienced steep losses from holding devalued real property assets that they could not dispose of without suffering additional losses. The damage caused to the financial sector spread to other important sectors. This resulted in the collapse of large financial institutions, bailouts of companies and financial enterprises by national institutions in the U.S. and other developed countries (particularly across vulnerable nation-state economies in Europe such as Portugal, Ireland, Greece, and Spain). Total losses exceeded trillions of dollars globally.

In this scenario, recovery never actually occurs to the extent that many forecasters expect or hope it will, and no return to “the course” prior to the crisis happens. Double-dip recessions occur in many economies. Massive borrowing to provide liquidity into markets drives up even more already difficult-to-sustain levels of national borrowing. This erodes market confidence and increases enterprise managers’ and investors’ reluctance to deploy their resources through further investments. Many countries must deal with austerity regimes. Thus, deep structural problems in global markets, along with higher-than-acceptable unemployment and underemployment rates, are exacerbated further. Consumers, shell-shocked by these events, go into “savings” mode instead of spending. As a result, housing markets remain depressed, consumers don’t improve already depreciated real property assets, and new-house starts and house-buying levels remain stagnant. The demand for and consumption levels of traditional lumber products stay at or near the low levels experienced during the recently passed crisis.

Scenario 3: Skyrocketing Energy Prices

Demand for energy products, some new forms of which are being produced by the forest products sector, has been tightly correlated to the overall demand over the last few years. Weak economic growth has reduced demand for traditional petroleum-based products. This has decreased the price of oil to lower levels than would have been the case in the absence of the recent economic crisis. In this scenario, economic growth in the next few years begins to raise demand for energy even beyond levels experienced pre-crisis. Economic prosperity, industrial development, and rapid urbanization in faster-growing economies such as China and India push the demand for petroleum products to high levels, thus raising energy consumption and prices of traditional energy sources.

Unfortunately, this scenario does not see the supply of these traditional energy sources keeping up with the increased levels of demand. Tighter credit supplies and insufficient investments in discovery and gas supply infrastructure coming out of the financial crisis limit production and lead to a prolonged period of tight supply. Although this situation also stimulates alternative energy sources and supplies, it is not enough to keep up with demand, and this pushes oil prices even higher. Peak oil theory, whereby the maximum rate of oil extraction has been reached, occurs. Petroleum resources dwindle further and faster, extraction costs increase, and prices charged to consumers rise accordingly.

Scenario 4: Emerging Carbon Economy

The continued burning of fossil fuels and deforestation have contributed to global warming. Protocols such as the one signed in 1997 at Kyoto are being pursued by national governments as a way to tackle greenhouse gas reduction. Governments investing heavily in alternative energy sources, increasing consumer interest in the use of renewable energy sources, and strong growth in the carbon market all contribute to the emerging carbon economy as characterized by this scenario.

Under this scenario, a dramatic growth in the pricing of carbon occurs through voluntary compliance efforts as well as regulatory penalty (such as fines) and taxation regimes. New efforts to build national and global carbon trading mechanisms quickly take hold, causing carbon to become a worldwide regulated commodity. Government policies dramatically turn toward fossil fuel usage reduction, thus allowing other power-generation alternatives, one of which is biomass-based generation from forest product sectors, to gain favor. Demand for carbon offsets increases, and forest lands grow in attractiveness and value as a key resource for solving the underlying problem.

Developed nations keep increasing their clean-energy resources, and developing economies also track this trend, albeit at a more moderate pace. Financial initiatives grow in number and variety to attract investors to the sector. Clean-energy technologies get less expensive. Biofuel prices decrease as algae, nonfood feedstock, and waste streams become harvestable. The public’s attitude toward energy-efficient technologies continues to improve.

Business Implications of These Scenarios

Depending on the strategies undertaken, resources used, and capabilities leveraged, each of these four scenarios suggests conditions for the future emergence of different winners and losers. This is one of the reasons why scenario analysis is such a critical analytical tool in helping your business develop a more robust strategy.

Under the first scenario, the traditional analyses of companies, markets, and industry attractiveness (as discussed in Chapter 7 and our other books) should help you better understand who is likely to win and lose competitive battles. This scenario favors traditional forest product companies that are already well positioned and that can achieve economies of scale or differentiated end products. These businesses should continue to earn attractive profits, particularly if they are exporting their product to the fast-emerging economies of the developing world, which will be demanding more product proportionately than developed economies. Companies that develop nontraditional, renewable, and biomass-based energy sources need to carefully assess their markets, keeping a close eye on the STEEP environment and changing regulations that might tilt the playing field. Establishing early warning indicators that portend these “field tilting” shifts should be a high priority for these companies, giving them an early warning and helping them move quickly when these indicators become actionable.

Although many products will continue to see eroded profitability under the conditions of the second scenario, some products will find favor. Biocarbon and biomass products should see increasing commercial applications and consumer demand. Under these conditions, being able to effectively and efficiently operate at the leanest levels will be advantageous. Financial strategies that lessen the risk of dramatically or suddenly rising upstream and downstream costs will be more beneficial. Companies that can achieve and sustain scale and targeted scope economies will be better able to withstand these conditions than their less-efficient rivals.

Scenario 3 will require companies to be astute in their choices of where to operate (these are scope decisions) and with whom they choose to collaborate and partner. This scenario will see anticipated increases in fiber harvesting costs due to high fuel prices, reducing profit margins for traditional forest industry players. In this situation, partnership becomes a key strategy in the survival of companies. Higher oil prices will lead some energy producers to make plays for fiber. They also will increase competition for these resources and the environmental pressure on forests. Forest product producers that can efficiently provide and scale energy-related products will be highly favored in this scenario.

The fourth and last scenario has some highly robust and potentially valuable possibilities for strategy. The private ownership of forest lands becomes highly advantageous under this scenario. The clarity of ownership facilitates transacting carbon offset solutions, and forests are cost-effective sources of renewable energy. Companies that are already producing substantial quantities of biofuels will be in an advantageous and profitable position. Companies that can read better than their rivals the emerging significance of the carbon-conscious consumer, and that can provide a product that meets their demands, stand to be victorious under this scenario. Companies that are in value networks and supply chains with high exposure to the rising price of traditional fuels in the product conversion or transportation process will be most vulnerable under this scenario.

In thinking about the various strategy implications of these alternative scenarios, we want you to recognize that scenario planning is a practical and valuable way to challenge the assumptions you naturally tend to make about the situation in which your plans come to fruition. By building a few alternative scenarios, you can foresee more unknowns that may come to pass. Therefore, you will be able to plan measures to counteract or mitigate their impact.

Endnotes

1. Schoemaker, P.J.H., “How to link strategic vision to core capabilities,” Sloan Management Review, 34(1), 1992, 67–81; “Multiple scenario development: its conceptual and behavioral foundation,” Strategic Management Journal, 14, 1992, 193–213; and “Scenario planning: a tool for strategic thinking,” Sloan Management Review, 36(2), 1995, 25–39.

2. Fleisher, C.S. and B.E. Bensoussan, Strategic and Competitive Analysis: Methods and Techniques for Analyzing Business Competition, 2002, Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. See Chapter 19.

3. Adapted primarily from “Scenario Analysis: The Traditional and Emerging Forest Products Industry,” C. Palma, G. Bull, A. Goodison, and S. Northway, Forest Resources Management Working Paper, 2010:1, University of British Columbia and Forest Products Innovation.