2. The Analysis Process

Because of its lack of separate inclusion in most business schools and executive training programs, it is easy to see why analysis may be the ugly duckling of effective management. Few management authors write about analysis, not many people want to talk about it, and even fewer people claim to be an expert at it. Just compare the commercial availability and visibility of data analysis to data collection. Data collectors are found on every street corner—everywhere you can access a search engine. Data collection methods are common and available to most takers, and data collection agencies are plentiful. Don’t believe us? Go to your local library, search the Internet, or read the advertisements in industry magazines.

Why, then, does analysis have a poor reputation? In addition to the reasons described in Chapter 1, we think a number of reasons can potentially explain why analysis is not among the most popular topics of discussion at the executive dining table:

• Analysis is difficult for most people. As in nature, people tend to prefer taking the path of least resistance when it comes to putting forth effort or expending energy. In today’s turbocharged digital world, it is far easier to collect a lot of data than to work out what to do with it. This explains why one of the fastest-growing industries globally during the past decade has been digital storage.

• Hardly anybody analyzes their analysis! Few people actually detail the processes they use in analyzing business phenomena. Many people have difficulty even explaining how they reached their analysis conclusions. Fewer still use process maps and other improvement techniques to elevate their performance over time. It’s a bit like riding a bicycle: Many people jump on and ride, but they cannot explain how they do it to a novice or to a four-year-old hoping to get rid of her training wheels.

• Few people have publicly recognized or established analysis expertise. In many fields, there are clear-cut educational pathways and certification routes that people can take to demonstrate competence. They do not exist in analysis. Even those who have the expertise may be unable to teach or disseminate how to do it. Analysis skills can be developed over time as you grow in experience and knowledge.

• Few frameworks exist for understanding how the analysis component can be managed as an integral part of the larger decision-making process. Few individuals can thoughtfully explain how analysis can be successfully managed according to the “three E’s”: efficiency, effectiveness, and efficacy. Very few people assess and evaluate analytical quality and performance.

It is our view and the findings of several large-scale business surveys that data collection is managed far more successfully than analysis. We see a number of prevalent symptoms that suggest why analysis is not managed properly:

• Tool rut. Like the child who has a saw and begins to think everything she sees looks like wood that needs to be cut, people keep using the same analytical tools repeatedly. We describe this tendency to overuse the same tools as being in a “tool rut.” This is counter to the principle that, in addressing the complexity of this dynamic world, businesspeople need to look at and effectively apply numerous models to provide value.

• B-school recipe. Many individuals charged with doing analysis come from MBA programs where they were taught tried-and-tested recipes by instructors who lack competitive analysis experience and expertise or who have a financial and management accounting background. Strategy, business, and competitive analysis are as different from accounting analysis as strategy is from accounting.

• Ratio blinders. Most businesspeople perform analysis based on historical data and financial ratios. This can at best only provide comparison and tell them the size of the gap (the what) between two organizations on a particular data point or data set. It does not help explain the reasons for why the gap exists or how to close it. Most ratios also point to past actions, previous behavior, and prior performance. Analysis must always point toward the future.

• Convenience shopping. Individuals frequently perform analysis on the basis of the data they have as opposed to the data they should have. Because they have certain data at their disposal, they use the analytical technique that suits the data rather than focusing the analysis on their questions or the insights actually required. This is especially true when accountants are asked to do analysis and they provide outputs that reflect only financial manipulations.

As mentioned in Chapter 1, this is a book about analysis. We realize that using this term makes most businesspeople we advise and teach uncomfortable, particularly when we get past the smoke-and-mirrors level at which most people talk.

With the pace of change in today’s competitive global environment, organizations are constantly repositioning themselves to stay ahead of or catch up with their competition. As a result, organizations need to better understand and make sense of their environment and their evolving and dynamic position within it. This is the primary objective underlying the process of analysis.

Analysis is without a doubt one of the more difficult and critical roles a businessperson is called on to perform. Although, as mentioned here, great strides have been made in recent years in terms of planning analytical projects and collecting data, the same cannot be said of analysis.

As with the type of research formally taught to scientists, the analysis process can be viewed as having much in common with the scientific method. Analysts observe certain events, persons, or actions; develop a proposition or hypothesis to explain what they have observed; and then use the hypothesis to predict what may occur. These predictions can then be further assessed through additional observations or data, and the hypotheses can be modified based on the results. Few businesspeople act this systematically or comprehensively.

As mentioned, business management involves all aspects of a business. It requires knowledge and understanding of the environmental impacts on an organization to ensure that correct decisions are made. It is not about just looking at the best “fit” but also about taking into account the needs of different stakeholders and diagnosing factors required to create a good outcome.

So how do you formulate strategies and ensure they are the right ones? Only by carefully collecting, examining, and evaluating the facts can appropriate alternatives be weighed in light of organizational resources and requirements.

In today’s world of information overload, collecting more or new data or information is not, in the authors’ opinion, the key issue. Instead, examining and evaluating the information through analysis is the key to defining appropriate strategies and decisions. This process requires knowledge, skill, time, and effort. Although most organizations gather some form of competitive information, surprisingly few analyze it formally and integrate the results into their ongoing business decision-making and strategy development processes.

What Is Analysis?

When we use the word analysis, we mean the separation of the whole into its constituent parts to understand each part’s value, kind, quantity, or quality. It is not just about reasoning from the universal or general to the particular; nor is it about summarizing the information collected. It is about breaking an issue into its parts. Today’s executive mindset says that every organization needs at least some professionals who are actively engaged in evaluating and examining each part.

How do you evaluate and examine each part?

Analysis is a multifaceted, multidisciplinary combination of scientific and nonscientific processes by which an individual interprets the data or information to provide meaningful insights. It is used to derive correlations, evaluate trends and patterns, identify performance gaps, and, above all, identify and evaluate opportunities available to organizations. Analysis answers the critical “So what?” and “Now what?” questions about the data we gather and brings insight to bear directly on the decision-making process.

Effective analysis requires experience, good inputs, intuition, models, and, some would argue, even a dash of good luck. It requires constantly varying and balancing combinations of art and science, common sense and informed models, and intuition and instruction.

The reason we do analysis is that, although plenty of information may exist, the issues being analyzed often are complex, and the overall reality of the situation may not be all that obvious at first glance.

Figure 2.1 illustrates a generic approach to analysis.

Figure 2.1. A generic approach to analysis.

As a process, analysis depends on raw data. However, using just any data will not lead to effective analysis. The data collected and used to respond to your requirements needs to be assessed for its accuracy and reliability.

You need to be aware that understanding accuracy means recognizing, at a minimum, that not all data is of equal quality. Some data may be excellent, some marginal, some bad, and some might even be intended to deceive. You must assess your data sources to know whether input data is accurate and reliable. Invalid data nearly always produces invalid findings, or “garbage in, garbage out” as the adage goes.

Sources often have different reasons for supplying data. Knowing the reason that underlies an individual or group’s data is important in establishing the fit of these purposes for analysis. Some data sources are notorious for projecting biases onto data sets. For example, advocacy groups who have policy agendas often are prejudiced in the data they provide to policy makers, sometimes leaving out data that counters their positions while overemphasizing data in support of their positions. As you can appreciate, effective analysis relies on effective data collection and information gathering.

Apart from good data collection, there is no one best way to perform analysis. We have met many people who have wanted to drink from the mythical “analysis spring,” more popularly known as “magic bullet” software that will reliably perform the analysis task. It does not exist, and we strongly doubt that it ever will. However, we do believe it is possible to improve your expertise in this process by attending to certain things:

• Being extremely clear about what and how the decision-making client will use the results of your analysis

• Selecting and sorting data and informational inputs (that is, the “need to know” from the “nice to know” or “who cares about knowing” items)

• Choosing an analytical technique to apply to a particular need, as well as when and in what order to apply it

• Knowing what you need to understand and communicate to effectively inform organizational decisions and decision makers (that is, sense-giving)

Good analysis simply comes from ongoing practice. Like the top athlete who performs and improves his movements repeatedly until they can be done flawlessly, the more you practice the techniques described in this book, the better prepared you will be to undertake each technique, and the higher-quality your insights will be.

Whether the application of the analytical techniques can achieve its potential usefulness depends on a number of factors. Based on our experience with and understanding of the application of these techniques, you should keep in mind several points when performing formal analysis.

First, many organizations use formal methods as a way to take superficial shortcuts to management decision-making. The methods described in this book are based on empirical research and are supported by solid theory developed across a range of managerial disciplines. By presenting the methods individually and in a simplified fashion, we do not mean to suggest that their application can lead to “magic bullet” answers.

Second, there is no one right analytical tool for every situation. The depth and complexity of analysis depends on the business situation and your needs. It is important that you understand your needs first. No one method provides all the answers needed by decision makers who are intent on improving their competitiveness. Analytical techniques nearly always have to be used for specific purposes and in various combinations to obtain optimal results.

Third, you should be wary of becoming overly reliant on a small number of techniques. This is especially prevalent with inexperienced analysts and can happen for a few main reasons:

• They have generated positive results in the past by applying a particular technique.

• They have developed a level of comfort with using the technique.

• They possess convenient data that supports the repeated application of the same particular techniques.

The use of the techniques described in this book might lead you to circumvent the quality and/or quantity of analysis necessary for formulating and implementing effective competitive strategy for a number of reasons. For example, our experience suggests that it is far too easy to draw incorrect conclusions from incomplete or defective data with a number of these techniques. As mentioned earlier, the quality of the data is critical to the effective delivery of analytical outputs.

You should also note that in spite of the presence of a broad range of analytical techniques, twelve of which we describe in this book, some executives may still make poor decisions due to perceptual distortions and cognitive biases. Researchers have identified a variety of common biases that can enter into the process of analysis. These include the following:

• Escalating commitment. This is where executives commit more and more resources to a project even when they receive evidence that it is failing. The more rational move would be to cut your losses and run. But rationality is often overcome in these cases by feelings of personal responsibility, an inability to admit a mistake, or a failure to acknowledge changes in the assumptions that supported the initial decision.

• Groupthink. This occurs when a group of decision-makers (such as a senior management team) embarks on a poorly determined course of action without thoroughly questioning the decision’s underlying assumptions. It is often based on an emotional rather than objective assessment of the appropriate course of action and is most prevalent in organizations with strong leadership figures and cultures.

• Illusion of control. This is an individual’s tendency to overestimate his or her ability to control events. For example, someone who has chosen several winning lottery numbers might begin to believe he is better at it than he truly is. This is often the result of overconfidence. Senior executives have been shown to be particularly prone to this bias.

• The prior hypothesis bias. Individuals who have strong beliefs about the relationships between variables tend to make decisions on the basis of these beliefs, even when presented with analytical evidence that contradicts them. Additionally, these individuals often seek and use data only when it confirms their beliefs, while ignoring data that contradicts them. In strategic terms, this may happen when the top executive strongly believes that the organization’s existing strategy makes sense and continues to pursue it despite evidence that shows it is inappropriate.

• Simplification. This is where individuals use simple examples to make sense of not-so-simple problems. Oversimplifying complex problems is dangerous and can mislead an organization into making bad decisions. This is one of the key cautions we give in applying the techniques contained in this book.

• Representativeness. This is a bias that violates the statistical law of large numbers. Individuals often display a tendency to generalize from small samples (such as their experience) to explain a larger phenomenon or population.

The existence of these biases raises questions about the analytical process and its purpose and outcomes. People in organizations often tend to collect more information than strictly necessary for decision-making, partly to influence others and partly to be seen as working hard and rational. In other words, analysis is often used not just for objective decision-making but also for political purposes.

In fact, formal analysis would be less necessary if people could execute their decisions themselves and nobody had to convince anybody of anything.

Because of these issues and related problems, the techniques described in this book should never be used to circumvent the strategic thinking necessary to gain a thorough understanding of an organization’s business and competitive environment today or where it should be in the future. They will help improve strategic thinking but are not a replacement for it.

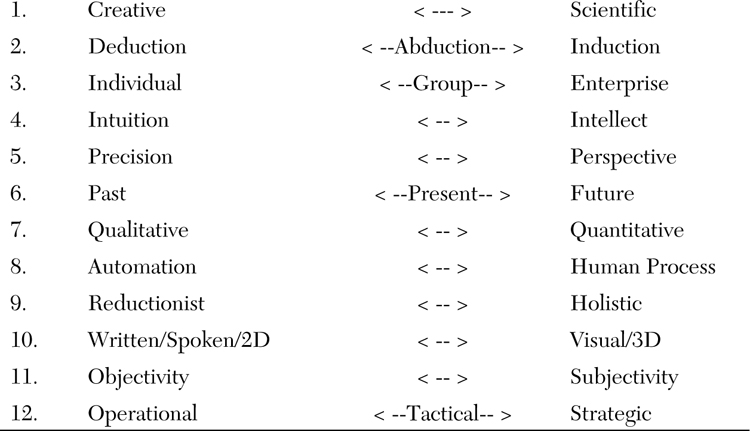

What does it take to successfully perform analysis? Becoming an effective analyst is somewhat like surfing—going out day after day, trying to find and make the most of the perfect wave when it arrives. Project by project, the best analysts constantly make trade-offs and reposition their idealized approaches along a dozen continua that are always a part of the analysis context, including the following:

Source: C.S. Fleisher and S. Wright, “Causes of competitive analysis failure: Understanding and responding to problems at the individual level,” Journal of Strategic Marketing, 2010, 18(7), pp. 553–572.

We could have described hundreds of strategic, tactical, and operational analysis techniques in this book. Instead, we have extensively reviewed the literature in the field and considered survey research and our own experiences in determining those we view as potentially being the most applicable across a broad range of applications in the analysis process.

As mentioned in Chapter 1, this book examines 12 so-called “classic” techniques for analyzing business and competitive data and information. These include environmental, industry, competitor, and organizational analysis models. These techniques will help any businessperson draw effective conclusions from limited data and put together information that does not often fit together at first glance.

Keep in mind that any listing of techniques is bound to run into problems with semantics and confusion over definitions. Some of the techniques described in this book are known by multiple names. This might have occurred because the technique came to be associated with a particular originating organization (such as the BCG matrix) or author (Porter’s Five Forces model is an example). Or perhaps the technique has retained a generic nomenclature (such as competitor analysis). We recognize that some of the techniques included in this book have seen modifications in use over the years or are derivatives of other closely related techniques. In all cases, we have tried to include and describe the most popularly known versions of the techniques as opposed to all of a technique’s possible derivatives. We have tried to alert you to where overlap exists between techniques by referring you to the supporting techniques within the text.

We must also note that it is not our intention to reinvent the wheel when it comes to analytical techniques. The techniques described in this book all have a history. They are used in real organizations. They do not exist just in classrooms or theory. They will work for you and be useful in analyzing your organization’s marketplace challenges and opportunities.