7. Five Forces Industry Analysis

Description and Purpose

The Five Forces Industry Analysis, developed and popularized by Michael Porter, is designed to help you understand an industry and its participants. Since the intensity of competition and profitability among companies can vary widely across industries, identifying an industry’s profit potential or “attractiveness” provides the foundation for bridging the gap between your firm’s external environment and internal resources.

The Five Forces Industry Analysis is one of the most highly utilized analytical tools for assessing the competitive environment. The framework Porter developed is based on an economic model known as the “structure-conduct-performance” or S-C-P model. It states that an industry’s structure will determine an organization’s conduct, which subsequently determines its performance (profitability).

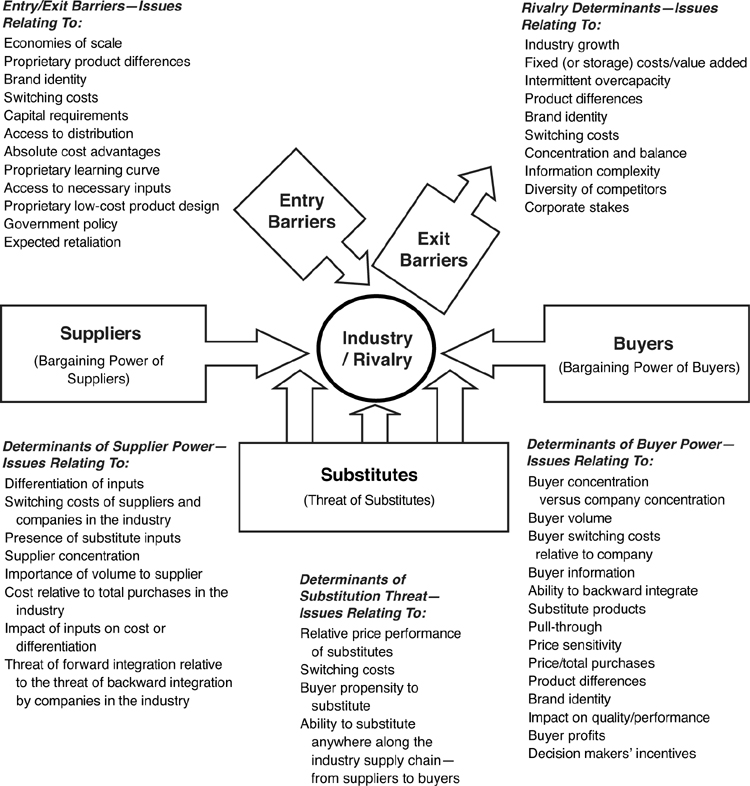

The purpose of industry analysis is to analyze the economic and market forces that will ultimately influence an industry’s profit potential. It enables your organization to determine the attractiveness or profit potential of a focal industry by rigorously examining the interaction of five competitive forces. Porter classifies the five forces or “rules of industry competition” as follows (see Figure 7.1):

• Threat of new entrants

• Bargaining power of suppliers

• Bargaining power of buyers

• Threat of substitute products or services

• Degree of rivalry among existing competitors

Figure 7.1. Industry analysis.

Source: Adapted from Porter, M.E., Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance (London: Collier Macmillan Publishers, 1985).

The objective of this analysis is to

• Identify an industry’s profit potential

• Identify the forces that would harm your company’s profitability in that industry

• Protect and extend your competitive advantage

• Anticipate changes in industry structure

A proper understanding of the five forces is important in developing your company’s competitive strategy. The collective impact of these competitive forces is so brutal in some industries that the market is very unattractive from the standpoint of profit making. The ultimate aim of the analysis is to develop competitive actions, capabilities, and resources to cope with and, ideally, influence or change these forces in favor of your firm. Those companies that successfully do this aim to develop competitive advantages that can be sustained over time.

Using this analysis, an incumbent firm can, for example, determine that it can better leverage its resources and capabilities in a different industry. As such, it may decide to exit the industry entirely or allocate resources away from the current industry toward a more favorable one. It also helps decision makers understand where their organization is in relation to their industry. This differentiates it from the SWOT analysis we present in Chapter 12, “SWOT Analysis,” as SWOT analysis is company-specific while Five Forces Industry Analysis focuses at the industry level.

The scope of each of the five forces is covered in the following sections.

Threat of New Entrants

The threat of new entrants is the extent to which new organizations may decide to enter an industry and reduce the profits being earned by incumbent firms. All else being equal, industries that are easy for new organizations to enter are more difficult to profitably compete in than ones with higher barriers. The nature of entry barriers affects the level of difficulty facing companies that want to enter an industry. If entry barriers are low, new entrants generate additional capacity, increase the demand and prices for inputs, and intensify the competition, resulting in lower industry profitability.

New entrants ordinarily face several entry barriers:

• Entry-deterring price. The cost of entry exceeds revenue forecasts. Often, existing players lower their prices to thwart a competitive entry.

• Incumbent retaliation. Existing companies often have substantial resources and the willpower to fight new entrants.

• High entry costs. Often, substantial portions of the start-up costs are unrecoverable.

• Experience effects. The accumulated experience of existing companies in the industry often translates into lower cost structures.

• Other cost advantages. Existing companies may already control access to valuable inputs and suppliers, proprietary technology, or the best locations.

• Product differentiation. The high cost of marketing new brands may pose significant entry barriers not faced by existing companies that have well-known brands, customer loyalty, and the flexibility to cobrand other products.

• Distribution access. This includes the need to pay incentives to distributors to persuade them to carry new products.

• Government. Public bodies can provide subsidies for existing companies, enforce compliance with regulations, or develop policies that restrict entry.

• Switching costs. It can be expensive or inconvenient for customers to switch to a new product.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers

Suppliers can exert bargaining power of an industry’s participants by increasing prices for their goods and services or by reducing the quality of purchased goods and services. Suppliers might be able to influence the cost, availability, and quality of input resources for companies in the industry.

When considering this force, the buyer is the incumbent firm in the industry and the supplier is the producer of that company’s inputs. Suppliers must be thought of more broadly than just those providing raw material inputs. This group can also include groups governing or providing labor (trade unions or professional bodies, for example), locations (landing slots at airports), or channels (the broadcasting spectrum), among other things.

Suppliers’ bargaining power may be influenced by the following:

• Concentration. Supplier bargaining power is high where an industry is dominated by fewer players than the industry it sells to unless substitute inputs are available.

• Diversification. The proportion of total sales that a supplier has with a particular industry varies inversely with supplier power. For example, if a supplier’s revenue is totally sourced from one industry, its power over the industry is lower than a supplier that sells only 20% of its total goods to an industry.

• Switching costs. Supplier bargaining power is weaker if companies in an industry can switch suppliers easily or inexpensively.

• Organization. Supplier organizations, industry associations/groups, trade unions, or the presence of patents or copyrights increase supplier power and thus their collective bargaining power.

• Government. In many economies, the government can function as a supplier, whether of land, rights to compete, licenses, and so on, and therefore can exert substantial bargaining power.

Bargaining Power of Buyers

Buyers can influence industry structure and force prices down through such actions as comparison shopping or raising quality expectations. They can also play incumbents against one another. The power of buyers reflects the extent to which their purchase represents a considerable portion of your organization’s overall sales.

Buyers’ bargaining power may be influenced by the following:

• Differentiation. Products with unique attributes decrease buyers’ power. Commodity products that are difficult to distinguish increase their power.

• Concentration. Where there are few buyers and they represent a large proportion of a company’s sales (for example, a government body that serves as the primary buyer of pharmaceuticals for citizens living within its boundaries), buyer power is high.

• Profitability. Buyers with low margins, lesser resources, or lower profits are more price-sensitive.

• Quality or Image. Where quality or image is important, buyers may be less price-sensitive.

Threat of Substitute Products or Services

An organization must worry about more than just competition from rival companies within the industry seeking to provide similar products or services to a group of customers. It also needs to concern itself with companies from outside the existing industry seeking to provide alternatives not offered by companies in the existing industry. By placing a cap on the prices incumbent companies can profitably charge, substitutes limit the industry’s potential returns. Industry competitors always prefer the threat of substitute products or services to be low.

Examples of substitute include e-mails, instant messages, faxes, and digital delivery for document delivery companies or video teleconferences instead of airline travel to meetings or conventions. In trying to better assess the impact of substitutes, you will need to identify products and services which can perform essentially the same functions as your industry’s products and services. Often, this is harder to do than it appears because incumbents develop “blinder mentalities” about their industries over time. Blind spots also prevent the timely identification of disruptive substitutes that are offering somewhat similar products or services at much lower price points.

The existence of viable substitutes means that customers can switch to these company’s products in response to price increases or product/service decreases. The more attractive the price to performance ratio of substitute products and services, the greater is the restraint on your industry’s profits. Market displacement and disruption by existing or potential substitutes can be influenced by the following:

• Relative price/performance trade-off. The risk of substitutes is great where existing products or services offer favorable attributes at low cost.

• Switching costs. The threat of substitution is low where switching costs—from one product or service that customers are currently using—are high.

• Profitability. A reliable substitute product that is profitable may displace or disrupt existing products.

Degree of Rivalry Among Existing Players

Of all the five forces, rivalry among existing players is nearly always the most important in determining an industry’s attractiveness and potential profitability. When organizations in an industry exhibit a high degree of rivalry, industry profits will be decreased. Such rivalry often takes the form of rivals competing aggressively on price. Since price reductions can be easily matched by rivals, they lower the profits for the industry’s incumbents. This is why actions like marketing, innovations, and enhanced customer service are used since they can often expand overall customer demand for the products or services offered in an industry.

All else being equal, existing companies in an industry prefer to face lesser competitive intensity and rivalry. Strangely enough, and for a variety of sometimes counterintuitive reasons, some degree of rivalry and a small number of competitors typically are superior to no rivalry or what is otherwise known as a monopoly.

The intensity of competition within an industry is determined by the following:

• Market growth. When strong, market growth in the existing industry reduces rivalry and thereby the probability of retaliation.

• Number of Competitors. Rivalry intensifies when there are a larger number of competing firms.

• Competitor capability or size. When competitors are of roughly equal capability levels or sizes, rivalry will intensify.

• Cost and price structures. When fixed costs are high, overcapacity occurs during demand troughs, and the fight for market share by existing rivals intensifies. When product or service prices are falling, rivalry also intensifies.

• Barriers to entry and exit. When entry barriers are low, rivalry increases. For low-profit companies, barriers to exit include asset specialization, fixed costs of exit, emotional attachment, or the product’s market importance in a company’s overall strategic intentions. The higher these are, the more intense the rivalry in an industry.

• Product switching. Product differentiation may keep customers from switching to competitors.

• Diversity. Where an industry has many companies of equal size and competitive position, rivalry is more intense. Entry from different sources, such as the Internet, also increases rivalry.

Strengths

Five Forces Industry Analysis helps you identify the main sources of competition and their respective strengths. It also helps you build a strong market position based on competitive advantage.

This technique, in fact, provides the raw analytical framework necessary to develop a strategy that will help insulate your company from competitive forces and provide it with competitive advantage. Additionally, it is a good technique for understanding industry evolution, because it allows you to identify windows of opportunity to capitalize on changes in any of the five forces.

Central to this technique, particularly when you’re trying to understand how an industry will evolve, is discovering that a change in one force will affect the other forces. This may result in the alteration of an industry’s structure and boundaries. This analysis can then do the following:

• Forecast future changes in each of the five competitive forces

• Discover how these changes will affect the other forces

• Identify how the interrelated changes will affect the industry’s future profitability

• Discover the strength of your company’s position in this evolved industry

• Reveal how you might change the strategy to exploit the changing industry structure

The Five Forces model also helps with long-range planning. It focuses your attention on the mutual dependency between the industry forces that change over time and the fact that a business strategy should both reactively defend against and actively manage these forces.

Weaknesses

The main weakness, according to critics of the Five Forces model, is that it underestimates the core competencies or capabilities that may serve as a company’s competitive advantage in the long term. Industry structure is one factor that determines a company’s profitability—others such as unique organizational resources are important as well. The model is designed to analyze individual business unit strategies within unique industries. It does not take into account the synergies and interdependencies within a corporation’s overall portfolio.

Strict interpretations of the model do not fully recognize the importance of social and political factors within or affecting each of the five forces. For example, the role and influence of government as an industry stakeholder, which some argue should be treated as a separate sixth force, can directly impinge on the industry’s competitive parameters.

Porter himself has acknowledged that the Five Forces model is concerned primarily with what makes some industries, and some positions within them, more attractive. But it does not directly address why or how some companies get into advantageous positions in the first place, and why some sustain these positions over time while others do not.

The implicit advice that the Five Forces model delivers for formulating strategy may misdirect a company to focus on industry-level characteristics. The company may allocate resources for influencing the industry’s structure even though it may not uniquely benefit from the changes. It also may allow competitors to benefit from the changes. This course of action may be justifiable if industry structure is the dominant determinant of company performance.

How to Do It

Applying the Five Forces model involves three major steps and several substeps, as described in the following sections. We will note up front that it is important to recognize that this analysis is always done from the perspective of an incumbent organization already operating within the focal industry. This analysis is also best utilized at the strategic business unit (SBU) level of your organization.

Step 1: Collect Information

The first step involves specifically identifying your industry. This is not always easy; you might have to try several means. You might look at existing demand and supply patterns for specific products and services, using preexisting classification sources such as the International Standard Industrial Classification system (also known as the standard industrial classification [SIC] or North American Industry Classification System [NAICS]). Or you might gain agreement from business experts familiar with your competitive context. After you identify the industry, you need to collect information to identify the characteristics of each of the five forces and then examine and assess their impact on the industry.

Much of the information required in this step can be obtained from published sources. But it is important to use human sources where possible to improve the objectivity of your analysis and to identify possible market intentions. This process requires you to identify the main sources of competitive pressures:

• Degree of rivalry among competitors

• Threat of substitute products

• Threat of potential entry

• Bargaining power of suppliers

• Bargaining power of buyers

Step 2: Assess and Evaluate

The second step involves assessing and evaluating the five forces in light of your organization’s and other rivals’ competitive ability. This includes determining the force’s direction (which can be depicted as an arrow) to or from the industry and its relative strength. Each force receives a value indicating if it is strong, moderate, or weak. One way to do this is to use a scale of 1 to 5, with 1 indicating a weak force and 5 indicating a strong force (see the case studies at the end of this chapter). An important input into this process is providing a logical explanation of how each competitive force works and its role in the overall competitive picture.

For example, the competitive environment is unattractive and profitability is harder to achieve when rivalry is strong, competition from substitutes is strong, barriers to entry are low, and suppliers and buyers have considerable bargaining power.

The competitive environment is attractive and profits are more easily generated when rivalry is low to moderate, there are no good substitutes, barriers to entry are relatively high, and suppliers and buyers have poor bargaining power. The returns earned by rivals in these attractive industries should, on average, be greater over a designated span of years than those earned by rivals in unattractive ones.

A company whose strategy and market position demonstrate a good understanding of these five forces can earn above-average or supernormal profits even when some or all of the five forces are strong.

The ultimate goal of most business or competitive analysis is to identify a company’s ability to successfully compete within its industry, given the collective strength of the five forces. Comparing your company’s resource strength to the size of the “fit” gap with each of these five forces will provide valuable insight into strategic opportunities and threats.

Step 3: Develop a Strategy

The third step requires repeating the first two steps in light of industry change and evolution. To improve the usefulness of this analysis, long-term industry trends should be analyzed to determine whether the industry’s profitability is sustainable and how this will affect a company’s competitive position. Trends include, among other things, proposed government legislation and regulations, social and consumer trends, international changes and trends, guiding economic forces, and technological trends. We frequently link trend analysis that might come from doing a STEEP/PEST analysis like we describe in Chapter 11, “Macroenvironmental (STEEP/PEST) Analysis,” to complement the Five Forces Industry Analysis.

Now, integrate these long-term trends within the broader context of corporate strategy to find the best “fit” between your company’s resources and capabilities and the external environment. This involves three types of strategic scenarios: reactive strategy against likely competitor moves, proactive strategy to manipulate changing forces already in motion, and proactive strategy to explicitly force change in one or all of the five forces.

Industry structure fundamentally affects strategic choices. Understanding how an industry will evolve provides important direction for selecting and managing strategy for these five criteria. Each competitive force should be constantly monitored for its impact on your overall company strategy and the opportunities it represents for extending competitive advantage. You must also consider the interactions among these forces and trends.

Finally, not all industries are alike. For companies with product portfolios across numerous industries, this technique should be repeated for each industry.

Case Study: Applying the Five Forces Model to the U.S. Passenger Airline Industry

An airline’s profits depend on its revenue and its costs. Revenue depends on what a carrier is able to charge for its flights and the number of passengers it carries. Costs depend on, among other factors, the price of jet fuel and the wages and salaries of (often unionized) employees like flight attendants and pilots.

Since the end of the World War II, operating profits in the industry have ranged from the low teens to losses of around 10%. Operating profits over that period averaged in the mid-single digits, and losses for a year or more were not uncommon. From 2000–2010, six major U.S. airlines filed for bankruptcy. Surprisingly, this action was not due to poor or low demand, but rather because of difficulties in maintaining profitable pricing levels and inconsistent profitability exacerbated by increasing and often volatile fuel costs and a persistent gap between company costs and ticket fares.

What follows is a summarized Five Forces Industry Analysis of the U.S. passenger airline industry at the start of 2012. A rich understanding of the Five Forces can help the analyst to better understand how profitability has behaved for this industry.

(5 = strongest force, 1 = weakest force)

Threat of Entry: weighting 4

• High capital intensity, offset to a lesser degree by the ability to lease aircraft and hire ground crews on contract.

• Limited availability of terminal slots, offset to some degree by use of secondary or less-accessible airports.

Threat of Substitutes: weighting 3

• Improved information and communication technologies lessen the need for some forms of physical air travel.

• Market growth of the profitable business class is slowing due to the impact of information technology reducing the need for face-to-face communication.

• Recent political interest in increasing funding to high speed inter-city and inter-state rail projects will increase demand for that alternative mode of transportation. Similar funding increases are being seen in highway construction, thus also increasing demand for travel by automobile on shorter transportation routes.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: weighting 4

• Hypercompetition has caused air travel to more closely resemble a commodity, resulting in overcapacity.

• Consumers’ price sensitivity has not been significantly offset by loyalty programs.

• Air travel websites have made real-time pricing and other travel considerations more readily available.

• Ticket sales through rivals’ websites lessens travel agents’ commissions.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: weighting 4

• Increasingly militant and “under pressure” unions (flight attendants, machinists, pilots) have been bargaining more fiercely and are keen not to lose impressive wage gains made decades ago.

• There are very few suppliers of aircraft for certain forms of long-distance travel (such as transoceanic).

• Public entities have been less likely to provide public funding for airport expansion, new terminal slots, or longer/more runways.

• Bankruptcy regulations allow existing competitors to favorably restructure existing contracts and lessen the financial burdens created by some suppliers.

Degree of Competitive Rivalry: weighting 4.5

• Market share warfare is the industry norm.

• Some long-standing carriers, particularly the full-service, long-haul-oriented ones, have folded or gone into bankruptcy.

• Competition frequently devolves into pricing considerations.

• Growth in the travel class is offset by larger planes and competitive entry, resulting in overcapacity and lower margins.

• A high proportion of fixed costs and resulting variable-cost pricing through heavy discounting maximize the contribution margin from excess capacity.

• Larger, more heavily invested “legacy” carriers have high exit barriers.

Conclusion: All the competitive forces are at least moderately strong and in some cases are very strong. The attractiveness of the airline industry is low, and it will generally be difficult to sustain attractive levels of profitability in light of the current set of forces. However, despite this, some low-cost carriers like Southwest Airlines and JetBlue Airways Corp. have managed to create strategies that effectively offset many of the negative forces and achieve reasonable levels of profitability. This reinforces the need we previously described to develop effective strategies in light of the forces and trends affecting them.

Case Study: Applying the Five Forces Model to the Global Pharmaceutical Industry

The global pharmaceutical industry consists of companies that discover, develop, and deliver “branded” medicines (or drugs) designed to treat a variety of illnesses and improve health outcomes. Companies like Pfizer, Merck, Glaxo SmithKline, Eli Lilly, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Sanofi often compete with one another across segments of this large, global industry. For the industry’s products to be effective, it is essential that its products are safe, effective, high quality, and are properly prescribed and used.

For decades, companies have developed and sold drugs to help medical professionals treat a variety of adverse health conditions. Drugs made available to the public must first go through rigorous testing in most countries, which can often take many years and result in the country’s regulators declining approval to sell the drug due to ineffectiveness as demonstrated by the testing. For those very few compounds which can successfully navigate these processes, they face competition from competing products as well as a number of substitute therapies and treatments. Some of these drugs achieved blockbuster status, generally thought of as reaching the annual level of USD$1 billion in sales.

Unlike the U.S. passenger airline industry we presented in the prior case study, the global pharmaceutical industry was generally deemed to be one of the more profitable industries to compete in the five decades following World War II. Strong management, blockbuster products, persistent demand for the industry’s products, and successful innovation all propelled the industry to achieve higher levels of average profitability than most other industries.

What follows is a summarized Five Forces Industry Analysis of the global pharmaceutical industry at the start of 2012. A rich understanding of the Five Forces can help the analyst to better understand the nature of profitability achieved within this industry.

(5 = strongest, 1 = weakest)

Threat of Entry: weighting 2.5

• A large amount of capital (the average drug requires $200 million in R&D) and substantial unrecoverable marketing expenditures are required.

• Hence, niche strategies are the only feasible basis of competition for new entrants that, if successful, are frequently subject to aggressive acquisition (that is, take-over) overtures.

• A high degree of specialized expertise is required to successfully participate over the long run.

• Patent protection promotes and protects innovation.

Threat of Substitutes: weighting 2

• Few substitutes exist for drug therapy, and it is often much cheaper than hands-on medical and surgical interventions.

• Generic products are available only after a lengthy period of patent protection disappears, and some pharmaceutical companies are manufacturing generic drugs.

• Other forms of therapy remain less trusted and typically are more risky from a scientific viewpoint than pharmaceuticals.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: weighting 1.5

• Doctors, rather than patients, usually make the purchase decision based on product attributes and efficacy, not price.

• When consumers do make the purchase decision, they show a high brand loyalty that works against private-label drugs.

• Some organized buying groups (health maintenance organizations, public bodies such as healthcare providers) have, to a degree, eroded the discretionary powers of pharmaceutical manufacturers.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: weighting 2

• Many of the raw inputs to pharmaceuticals are commodities.

• Biotechnology and gene therapy are still in the early life cycle stages of their development.

• Many of the promising new biotech companies have been or will be acquired by established drug companies.

• Highly specialized human resources can be difficult to acquire in some pharmaceutical therapy areas.

Degree of Competitive Rivalry: weighting 2.5

• Continual product innovation by rivals creates new or growing demand.

• Aging baby boomers and increasing life spans will foster growth.

• A high percentage of unrecoverable costs such as R&D, marketing, and distribution increase barriers to exit.

• The effect of high premiums offered by incumbents for acquisitions of smaller companies must be offset.

Conclusion: All the competitive forces now facing this industry are fairly weak to moderate. The industry’s attractiveness remains good. The profitability of rivals in the drug industry is still relatively high despite the fact that a number of the incumbents are producing generic drugs as well.

The analyst must be careful to consider existing and potential trends that may affect the forces and their interactions. While pharmaceutical companies continue to face challenges like patent expirations, pricing pressure, and increased pressure from generic products, continued growth in emerging markets and product approvals could help reduce the impact.

Based on the trends impacting each of the Five Forces a few years down the line, the pharmaceutical industry should conceivably show some signs of recovery. The industry will be out of a major patent expiration period, new high-potential products will be introduced, merged firms will have been integrated and efficiencies achieved—all of which should contribute significantly to results. Increased pipeline visibility and appropriate utilization of cash should increase average industry profitability.