5. Driving Forces Analysis

Description and Purpose

Driving forces analysis (DFA) is a way of understanding and accounting for change at the industry level. The drivers are clusters of trends that collectively influence changes to an industry’s structure and a rival’s competitive conduct. The term force suggests that the drivers can materially impact the firm’s future.

So what are driving forces (DFs)? Forces in every situation cause things to remain as they are or change. Forces that push toward change are called driving or helping forces. Forces that resist change are called restraining or hindering forces. When these forces are balanced vis-à-vis a focus, no change is likely to occur. When the net effect of these forces is altered and moves away from balance, change occurs in either a helpful or obstructive manner.

DFs are significant underlying “currents” that define and drive events and trends in certain directions. These forces typically are broad in scope, long-term in nature, and associated with some degree of uncertainty about their evolution. Examples of DFs include global population growth, institutional commitments to free markets and global trade, advancing use of web-based technology, and changes in the global climate.

Understanding the DFs is the first step toward establishing a framework for analyzing critical trends, particularly as they may impact the competitive environment facing an industry. Industry conditions change because forces are driving industry participants (competitors, customers, or suppliers) and related stakeholders (public policy-makers, advocacy groups) to alter their actions.

As a result, DFA plays a critical role in the larger strategy development process. DFs indicate the external factors likely to have the greatest impact on a firm in the near future. A firm must effectively address these forces if it is to achieve success. Effective analysis of driving forces compels executives and managers to think about the future and what’s on the horizon, and what actions the company needs to take to prepare. The real payoff of driving-forces analysis is helping decision-makers understand what changes the organization needs to make to its strategy and tactics to help it constructively address the impacts of the driving forces on its competitive ability.

Strengths

DFA is an essential component of several other analytical techniques, including environment (Chapter 11, “Macroenvironmental (STEEP/PEST) Analysis”) and industry analysis (see Chapter 7, “Five Forces Industry Analysis”). DFA requires you to take into account the macroenvironment that influences key industry or stakeholder factors likely to affect your firm. For example, government regulations about mergers and acquisitions might imply much about the nature of potential entrants to your industry or to existing players that might influence future competition, but there are also many less-obvious external factors.

DFs by nature imply change. Change often is a source of competitive advantages for astute industry competitors, or alternatively a source of competitive disadvantage for others oblivious to its impacts. Understanding DFs and their impacts requires executives to consider how conditions will evolve in and around their industries and consider these forces in their decisions and strategy. Nevertheless, change is not the only factor associated with DFs that firms need to take into account. Uncertainty, direction, and magnitude (amplitude) are other key elements that the analyst and the organization must confront as they make decisions and develop strategies.

DFA tends to receive a higher-than-average degree of managerial agreement, particularly when those same managers are involved in the consensus process used to identify and develop the driving forces. Senior managers often have seasoned insights that can provide valuable perspectives in the DFA process. Including managers and decision-makers in the DF identification and prioritization process can be a valuable part of getting everyone in the firm focused on the type of strategic thinking and competitive learning that tend to serve firms well in the long run.

DFA can be done in a less-data-intense fashion than many other techniques. It doesn’t necessarily require the firm to continually gather and process data, as many other analytical techniques do. Data gathering underlying DFA can also be easily supported through the skilled use of secondary research over the Internet. Almost every company can do this research with the assistance of individuals such as information professionals or librarians, who are trained in library and information sciences. The use of brainstorming, popular group consensus methods, and participative technology facilitates DFA. Last but not least, DFA can be done less frequently than what is required for many other tools while still being quite effective and useful.

Weaknesses

By itself, DFA cannot drive strategy formulation. It seldom specifically answers clients’ strategy questions. Other steps must be taken before organizational actions (strategies or tactics) can be determined, even after agreement on DFs is reached. In other words, just recognizing and agreeing on a critical DF does not tell decision-makers what they need to do. But it does tell them that this driving force will affect their future and that the decisions or strategies that need to be developed must take these impacts into account.

Because of their broad and interactive nature, DFs tend to be outside the control of any single organization to change. But you can change how the firm’s strategy or tactics take them into account. Firms do not “manage” the collective impact of DFs. Instead, they must manage their own responses toward them.

The process used to perform DFA nearly always needs to be inclusive and participative. This can be a problem in firms where key personnel are unavailable to participate or lack the time to give the necessary consideration to the DF development and prioritization process. Some firms have experienced difficulties in generating agreement on DFs or their prioritization, but this is mostly due to the organizational structure, communication or group scheduling failures, or internal politics.

DFA can suffer from many common internal organizational biases when they are generated using only internal personnel. This is because internal personnel tend to see the world through the same (potentially distorted) organizational lenses and often exhibit common blind spots or group thinking biases. As such, it is often useful to employ external resources such as skilled consultants, trend trackers, academics, or think tank experts to help the group reach consensus on the DFs.

How to Do It

Two essential steps are involved in performing DFA, each of which includes a number of subelements you must address before moving forward:

1. Identify the relevant DFs. First you must figure out which trend clusters are causing change, and then you separate the major causes of industry change from the less-important ones.

2. Assess the impact that the DFs will have on the industry. This involves identifying the small number of DFs that are likely to have the greatest impact on the industry and the firm over the agreed-upon time span.

Step 1: Identifying an Industry’s DFs

The first task in understanding industry evolution is to look for the DFs in the macro-environment that influence industry structure and competitive behavior. Changing government regulations, new technologies, judicial pronouncements, and evolving regulatory regimes are common areas of focus.

There are also less-obvious external factors. Being able to spot and understand these “hidden” or “below-the-surface” factors can often provide the basis of asymmetric competitive understanding, one of the best bases for developing strategy leading to competitive advantage. As such, identifying and assessing these fundamental factors is both the starting point and one of the objectives of scenario analysis.

DFs may seem obvious to one person but hidden to another; therefore, DFs should be identified in a group or team environment. It is helpful to run through this common list of DF categories: social forces/demographic developments, technological developments, economic developments and events, ecological developments, and political developments and events. These categories are associated with the STEEP analysis, covered in Chapter 11.

Some DFs are unique and specific to a particular industry’s situation; nevertheless, most DFs cut across broad swaths of the business environment. They are usually identified by the presence of patterns seen as events and trends, or trends that combine to create a force. Some of the more common DFs across various industries are as follows:

• Changes in the long-term industry growth rate

• Changes in who purchases the product and the manner in which it is used

• Changing societal concerns, attitudes, and lifestyles

• Diffusion of expertise across more firms and locations

• Election or political trends, government decisions, or shifting regulatory influences

• Growing use of social media, mobile interactivity, and web-based applications

• Important firms that enter or exit the industry

• Increasing globalization of the industry

• Innovation in communication and marketing

• Innovations in processes and products

• Major changes in customer needs and preferences

• Prominent changes in production costs and efficiencies

• Significant changes in uncertainty and business risk

• Technological change and manufacturing process innovation

So how do you discover an industry’s DFs? You should start by removing from the list all DFs that are irrelevant to your industry. For example, if you are a wholesaler or business-to-business (B2B) firm, you can probably eliminate end-user-type forces from the list. After eliminating the obvious ones, determine if another driving force cannot be readily subsumed inside one of those remaining on the list. If the answer is no, the force should be included in your planning considerations.

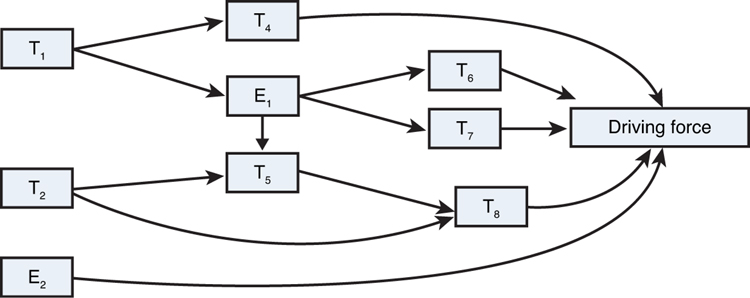

Another way of trying to understand DFs is to understand how trends (that is, T1 ... Tn) or events (E1 ... En) relate to one another and a potential driving force (see Figure 5.1). This process helps you understand the relationship between trends and events and determine truly independent driving forces as opposed to overlapping ones.

Figure 5.1. Relating trends and events to a driving force.

It is a rare analyst or group of managers who can look at their first list and focus on the key DFs. When these are presented to a group of managers, as most analysts do in their development of DFs, someone invariably rejects some of the suggested forces and proposes others. Our experience has shown that some of the most constructive debates occur when the DFs determination team tries to identify its relevant set of forces. Of course, things often get even more interesting when this step is complete and the impacts are discussed.

The following list shows the completion of the first stage by a management group at a large public flagship university in the U.S.

Societal and Demographic

Increased diversity of students seeking a university education

Questions about the value of some credentials, particularly relative to experience and academic credit granted for this

Increasingly blurred lines between trade, professional, on-the-job, and traditional postsecondary education

Increasing desire from individuals for lifelong learning

Long-held concerns about social inequities and fragmentation and underrepresentation of certain demographic groups

Increasing complexity of social problems that will face researchers and graduates

Continuing problems of getting enough 18-to-22-year-olds into college in primary catchment regions

Changing views about the appropriate role of universities, whether to educate students or to help them get started in their careers

Technological

Increasing demand for distance learning

Origination of new and improved pedagogical platforms

Expanded use of information technology in and out of the classroom

Escalating rates of innovation

Availability of context that can be applied in multiple platforms

Increasing value placed on knowledge

Economic

Continued globalization

Growth increasingly powered by entrepreneurship and smaller enterprises or organizations

Major increases in the number of students from China, India, and Mexico

Possible start of another lengthy recession following a tepid recovery

Unavailability of funding schemes or declining public funds to allow for easier access to a quality university education

Impact of interest rates on student loans

Impact of student loans on subsequent defaults of graduates and job prospects

Students need to conveniently attend classes and to avoid driving or flying long distances to attend them

Preferences for attending campuses that respect and protect their contiguous natural environment, ample green spaces, desirable climates, and in clean localities

Movement away from use of paper books to digital ones, renewable course materials, away from disposables in classroom instruction

Favorability of campuses that include “green” thinking, LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) certification, and sustainability in their design and building

Political

Ongoing blurring of postsecondary sector institutions such as two- and four-year colleges, technical institutes, and universities

Uncertainties about the direction of public support and advocacy for universities

Declining public funding as a percentage of total funding sources

Increasing government demand for accountability

Increased student activism due to higher tuition fees

This list illustrates a typical array of factors to emerge from this step. We recommend that you complete at least one other iteration to reduce these factors even further before assessing their relative impact in Step 2. At the end of this step you should have a manageable list of DFs to consider. Our experience suggests that the list should have about five to ten forces to facilitate the next step of this analysis process.

Step 2: Assessing the Impact of the DFs

Step 2 requires a more intense analytical effort than Step 1, because the DFs that remain on the list from Step 1 are all deemed to be important to some degree to the success of your industry and enterprise. All firms need to offer customers in their target markets products or services that meet their needs in a profitable manner, and the forces already identified affect all rivals in the industry. Now rank these DFs in order of importance in driving the attractiveness of the industry and the level of profitability that may be achieved in the near future. You also will provide a context in which strategy changes can be considered and thoughtful decisions made.

Your objective in this second step is to understand the external factors that will shape change in the industry and the difference they will make. As soon as the DFs have been identified in Step 1, you need to ask the following questions:

• Are they valid?

• How do we know?

• How significant is each one?

• What is their strength?

• Which ones can be altered?

• Which ones cannot be altered?

• Which ones can be altered quickly?

• Which ones can only be altered slowly?

• Which ones, if altered, would produce rapid change?

• Which ones would produce only slow change?

• What skills and/or information are needed and are available to change the forces?

• Can you get the resources or capabilities needed to change them?

Three common approaches to answer these questions are applied at this point.

The first approach is to use structured ranking. With a structured ranking approach, you need to consider all the DFs listed from Step 1 in pairwise progression. In other words, take DF 1 and compare it with DF 2. Decide which is more important to the industry and the firm when determining strategy, making major decisions, and setting important policies. Next, compare DF 1 with the remaining DFs, and then take DF 2 and compare it with the remaining DFs, and continue the process until all possible comparisons have been exhausted.

As you can quickly calculate, the number of pairwise comparisons grows rapidly with the number of DFs. Six DFs have 15 comparisons, eight DFs have 28 comparisons, and 10 DFs have 45 comparisons. You can readily see the advantages of taking care in selecting the initial DFs.

Our experience using this method is that some of the comparisons are quickly accomplished, and others bog down the group in discussion. It usually takes half a day to achieve consensus about the final list of DFs ranked in order of their impact. It is critical that you put in the appropriate effort at this point. This process will enhance the quality of any complementary efforts you subsequently undertake, particularly in support of regularly conducted planning activities.

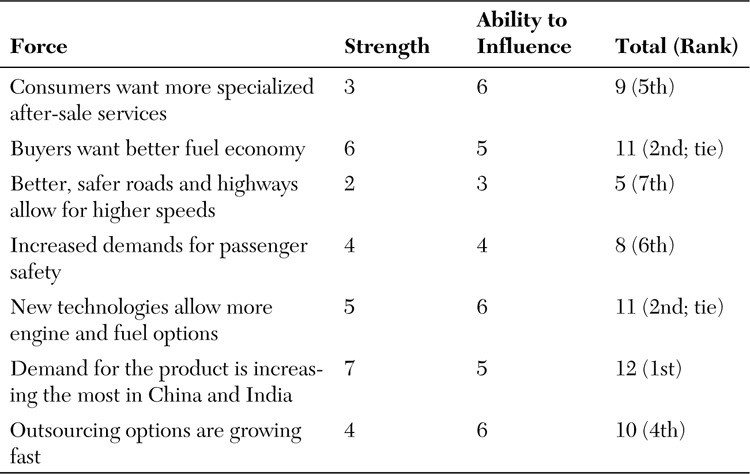

A second approach that many analysts take at this point is to assign a score to each DF, from 1 (weak) to 7 (strong). The score is based on the strength of the DF and the degree to which it is possible to influence it. This is often done best by circulating all the DFs to groups of relevant people around the organization and averaging their individual scores. Next, calculate a total score for each DF by adding across the two columns. Table 5.1 shows an example for a player in the transportation manufacturing industry.

Table 5.1. Ranking Driving Forces

The third approach is to use a matrix that separates the forces on preselected dimensions. Figure 5.2 uses importance and uncertainty to distinguish between the set of DFs. Importance rankings can be assigned to each DF in the list using a scale of 1 to 4, with 1 meaning lowest importance and 4 meaning highest importance. The same process can be used for uncertainty: 1 is assigned to the DF with the lowest uncertainty, and 4 is assigned to the DF with the highest uncertainty in terms of their depth, direction impact, and evolution. Those with mean scores above 2.5 in the relevant range are rated high in Figure 5.2, and those scoring below 2.5 are rated low.

Figure 5.2. Importance ranking of driving forces.

Regardless of which of the three approaches you choose, another key facet of this stage is to determine whether these DFs make the industry environment more or less attractive. As such, they should be combined with an industry analysis, possibly using Porter’s Five Forces model or something similar. Four strategic questions related to the DF’s impact on the industry environment must be answered:

• Are the DFs causing demand for the industry’s product to increase or decrease?

• Are the DFs making the bargaining power of other industry participants higher or lower?

• Are the DFs making competition more or less intense?

• Will the DFs likely lead to higher or lower industry profitability?

The following case study illustrates DFA as it is applied to the digital music player industry. This relatively youthful industry is an interesting case study for DFA, because in 2009 it was still in a somewhat early stage of its life cycle relative to the use of players for MP3 digital file formats. This industry also is a spin-off of portable music players that used to play music on CDs, which are in a mature stage of their life cycle.

After you have carried out these steps, your next task is to decide whether (strategic or tactical) actions taken to change the firm’s strategy to address the DF are feasible. If they are, your goal is to devise a manageable course of action that does the following:

• Strengthens DFs that have a positive impact on the industry and firm

• Weakens DFs that have an adverse impact on the industry and firm

• Creates new positive DFs

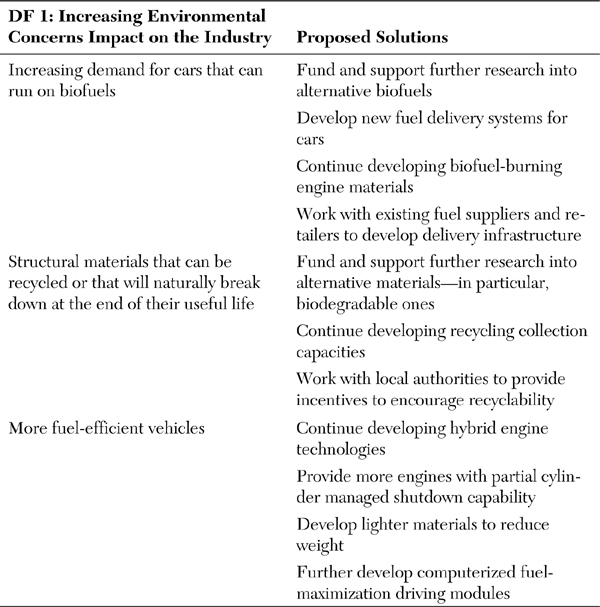

At this point, it is usually helpful for you to develop another set of tables, one for each DF that has been identified as a priority. For each table, outline in the first column the range of likely impacts that the DFs are expected to have on the industry. In the second column, begin identifying potential solutions that the firm may bring to bear in constructively addressing the impacts (that is, minimizing the negative effects and maximizing the positive effects). Table 5.2 is an example.

Table 5.2. Impact and Proposed Solutions for Driving Force 1

The next step would require you to work through each of the proposed solutions. You would need to compare these options in terms of costs/benefits, risks/benefits, or a predetermined set of criteria used to assess the options’ relative attractiveness and value. Comparing them against the firm’s current strategy is another key task to perform at this point. You need to gauge the degree of change required should the firm adopt the proposed solution, as well as the likelihood that the firm could implement it effectively. Finally, you need to analyze and identify the nature of competitor responses that the action may inspire. DFs and competitive pressures do not affect all competitors in an industry in the same manner. Profit prospects vary from rival to rival based on the relative attractiveness of their market positions and their strategies in addressing the DFs.

Case Study: Driving Forces in the Digital Music Market

This brief case study provides an example of DFA as applied to the digital music market as of the end of 2011 and start of 2012. The DFA helps you figure out which major DFs affect the digital music market and whether the forces indicate a more- or less-attractive industry environment from a profitability standpoint.

Demand Changes and Growth

The digital music sector, including players, services, and music files, has benefitted from strong consumer demand since the middle of the last decade. Sales of digital music and MP3/MP4 players have been impressive for years. But their growth rates recently have declined substantially because of competition from substitute products, mainly from the mobile telephone industry and smartphones.

Sales of downloaded music in the U.S. actually surpassed CD sales for the first time in 2012, according to a Nielsen and Billboard report. The International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (IFPI) estimated that about 3.6 billion albums and singles were downloaded around the globe in 2011. One artist, Bruno Mars, had nearly 30 million copies of his songs downloaded during the year. Revenues for digital music, the basic content input played on devices such as Apple’s iPod and increasingly smartphones, reached over $5 billion globally in 2011. Revenues are expected to keep growing at a brisk pace for the rest of the decade.

Technologies such as smartphones and tablets are not the only movers of demand for digital music. Popular TV shows focusing on musical performance talent such as American Idol, The X Factor, and The Voice also spur the public’s demand for music from new and emerging artists. Alternative delivery channels such as satellite radio services also help expand demand for the music while offering direct competition to manufacturers of digital music players. Access services of downloads and subscriptions; cloud technology; peer-to-peer channels; and bundling partnerships between musical content producers/distributors, ISPs, and telecoms are all encouraging demand growth in the market.

Product Innovation

Frequent product innovation is another characteristic of the digital music market. This product innovation in digital music players is largely focused on new product designs; enhanced functionality; user intuitiveness; and aesthetics that make the products more portable, pleasant to look at (some of these items are viewed as status symbols when worn by their owners in some parts of the world), and easier to use. Firms continue to add useful features to players such as telephone and photographic capabilities, touch screens, longer battery life, wireless file transfer, video-playing capacity, FM or satellite radio, appointment schedulers and calendars, contact databases, flash memory, and voice capture. Many manufacturers are known for their product innovation capabilities, including Apple, Creative, Microsoft, Philips, Samsung, and Sony.

Innovation also occurs in the delivery channels. Stores such as iTunes, AmazonMP3 music store, eMusic, Rhapsody, and Walmart are making it easier and less expensive for consumers to access music. Achieving scale through subscriptions services has become critical for players in this business. Several have done so by integrating their services through Facebook and similar social media channels. Internet radio services such as Pandora continue to grow, and companies such as Nokia have launched new apps to allow for personalized radio listening.

Consumer Choice

The growth being experienced is underpinned by several key driving forces, led by the continued widening of consumer choice. Global digital growth continues to accelerate. Some national markets, such as China, South Korea, and the U.S., now get more than half of their music revenues through digital channels. Digital music has become broadly segmented into two main consumption models—ownership and access. Music subscription services expanded and linked with new partners to reach new audiences—most notably integrating with Facebook—and bundling their services with other Internet service providers’ offerings. Meanwhile, developments in cloud technology are transforming how consumers manage and retain their music. Both models—access and ownership—are believed to have high growth potential, although unauthorized or illegal downloading services still remain easily accessible for many customers.

Growing Use of the Internet, Satellite, and Smartphones

The increasing global adoption of broadband Internet service, satellite content delivery such as through Sirius/XM in the U.S. or RTE in the UK, and wireless mobile communication devices such as smartphones will help drive the market forward by increasing the source of supply and demand for the music to be played on the industry’s devices. This also creates a need for a portable way to maintain your MP3 or video collections. This factor could especially benefit the manufacturers whose players are identified with popular subscription services. The ability to download a large amount of music or video in a relatively short time is a success factor for that segment of the MP3 and MP4 value chain. Growing use of the Internet and wireless communications will also lead to better informed and more MP4-amenable customers.

Changes in Who Uses the Product and How It Is Used

An increasingly diverse global customer base is using the industry’s products in more varied ways. The industry’s products have moved up the product life cycle from early adopters to the mainstream. Consequently, users are becoming less technologically sophisticated and more demanding in terms of functionality, style, and price. This also changes the nature of tactics and strategies that the major players in the industry will use to be successful, particularly in areas such as pricing, promotion, advertising, manufacturing, and branding concerns.

How Do These DFs Affect Demand, Profitability, and Market Attractiveness?

You can further analyze the effect of DFs in this market by answering the following four questions:

• How do DFs affect demand? Virtually all these changes should increase the level of demand for the market’s products. Increasing product innovation, especially in the area of convergence with tablet, wireless, or telephone (such as smartphone) functionality, should lead to higher demand, especially from existing device owners. Growing use of the Internet, satellite services, and increasing broadband availability should also be a demand driver. It increases the volume of content available, as well as the global population of individuals who can potentially use the market’s products.

• Are the DFs making the bargaining power of other industry participants higher or lower? This market is seeing a tug of war across a variety of dimensions. Some will strengthen the bargaining power of market incumbents, and others will strengthen the power of consumers, suppliers, or substitutes. The resolution of digital rights issues will clearly empower some players, whether it will be consumers who will have more options for their digital music enjoyment, record firms, or artists. Also, the eventual resolution of the format wars will also clearly empower some industry participants while neutralizing the prospects of others. The question of which industries hold power with respect to content generation, delivery, storage, and distribution will remain contentious. As such, a high degree of uncertainty surrounds the resolution of this driving trend. However, it will have a significant impact on some firms, and industry participants will need to develop flexible strategies and contingency plans in case the trends go against their current strategy.

• Are the DFs increasing competition? There is no doubt that the increased demand for, and increasing profitability of, products such as Apple’s iPod and iPad will entice new and potentially powerful electronics manufacturers into the industry. The threat of new entrants, particularly in just-emerging national markets, will be present for the remainder of the decade. Substitutes in the form of subscriptions to satellite radio and wireless mobile connectivity to digital music available through smartphones are key factors in the rivalry among sellers in the market. The high threat will cause the current players to compete against both each other and new entrants, specifically in the areas of product innovation and creating economies of scale. This will occur through rapidly developing critical customer mass, whether from subscriptions, access to content generation, or access to bundling partners. In summary, the DFs are increasing competition across a range of competitive vectors.

• Will the DFs lead to higher profitability? New entrants are expected to arise in the market, particularly as global growth and new markets become robust, which in turn will increase supply. Demand will continue to increase due to product innovations, market growth, broadcast interest in music, and the increased evolution and advancement of Internet and global wireless mobile communications usage. It will be interesting to see whether demand or supply will be the stronger force in the coming years. It is reasonable to conclude that profitability will likely be based more on volume than margin in the future. This is a natural occurrence as a market matures.

However, the slowing expansion of the no-longer-new market should help limit the onset or duration of price wars. Margins probably won’t be cut to too great a degree. Because of these factors, the market should still be profitable, at least in the short term. This will be especially true for firms that can continue to efficiently add innovative features and access to content to their products that appeal to more mainstream users. Achieving critical mass quickly will remain the strategic objective of most players in the market that intend to achieve satisfactory profitability and remain competitive over the next decade.