13. Value Chain Analysis

Description and Purpose

Value chain analysis (VCA) is used to identify a company’s potential sources of economic advantage and to achieve an optimal allocation of resources. For our purposes, a value chain can be defined as the full range of sequential organizational activities that are needed to take products and services from the original idea through the different stages of production. This includes the physical transformation and inputs of various producer services, delivery, and post-sale services to final customers. Value chains within a company or industry are actually composed of a specific model of performance characterizing the discrete stages of organizational value creation.

A company’s value chain is part of a larger industry value system. It includes the value-creating activities of all the industry participants, from raw-materials suppliers to the final consumer. VCA separates the company’s processes into strategically relevant value-creating activities. This analysis provides rich insights into where enhanced profitability can be achieved and helps you identify strategies needed to generate competitive advantage.

The unique strength of VCA is that it can be used to help companies bridge the strategic gaps between their capabilities—aspects of the business that employ resources effectively and perform well—and opportunities and threats in their competitive environments. Hence, VCA’s two main objectives are to identify opportunities to secure cost advantages and to create customer-satisfying product/service attribute differentiation. Cost advantages can be achieved by reconfiguring the entire value chain to lessen overall costs or the costs of any of the key activities along the chain. Likewise, differentiation can be achieved through value chain reconfiguration or by delivering innovative ways of generating higher value from a particular activity or set of linked activities.

The value chain concept has been helping companies since Michael Porter popularized the concept in his 1985 book, Competitive Advantage (see Figure 13.1).

Figure 13.1. The value chain.

Source: Adapted from Porter, M.E., Competitive Advantage (New York: The Free Press, 1985).

In reality, value chains are more complex than the simplified version shown in Figure 13.1. In many cases, the input and output chains comprise more than one channel, and these channels can supply more than a single market. Porter classifies all these activities into two main categories.

Primary activities include the following:

• Inbound logistics are activities in which resources are acquired for later processing by the business, including such areas as inventory warehousing and handling.

• Operations are activities that transform the gathered inputs into the final product or service.

• Outbound logistics are distribution-oriented activities such as logistics and shipping.

• Marketing and sales are all the activities designed to communicate the product’s or service’s benefits to consumers, such as marketing communications, pricing, and channel management.

• Services include post-sale support activities.

Support activities include all the important activities that cut across the company’s primary activities and provide ongoing infrastructure assistance for the rest of the organization. These activities differ by industry and company, but they generally include the following:

• Firm infrastructure includes administrative support activities covering the range of primary activities, such as accounting, legal, planning, and all forms of stakeholder relations, such as government and public affairs, communications, community investment, and investor relations.

• Human capital management includes aspects of the company and its human capital enhancement process, such as recruitment, incentive systems, motivation, training, promotion, and industrial/labor relations.

• Procurement includes activities such as funding, subcontracting, supplier management, and specification.

• Systems and technology includes infrastructure facets of the business that help design, develop, and/or deliver products more effectively and efficiently, such as engineering, R&D, and information technology.

VCA is especially useful for identifying value chain activities linking management and strategies that allow your organization to create customer value in excess of the costs of delivering that value. This is the source of a company’s profit and the relevant definition of profit margin. The price charged to the company’s customers, minus the costs of all these activities, determines the company’s profit. You should determine if your organization is deriving its highest potential margin from the activities it chooses to participate in.

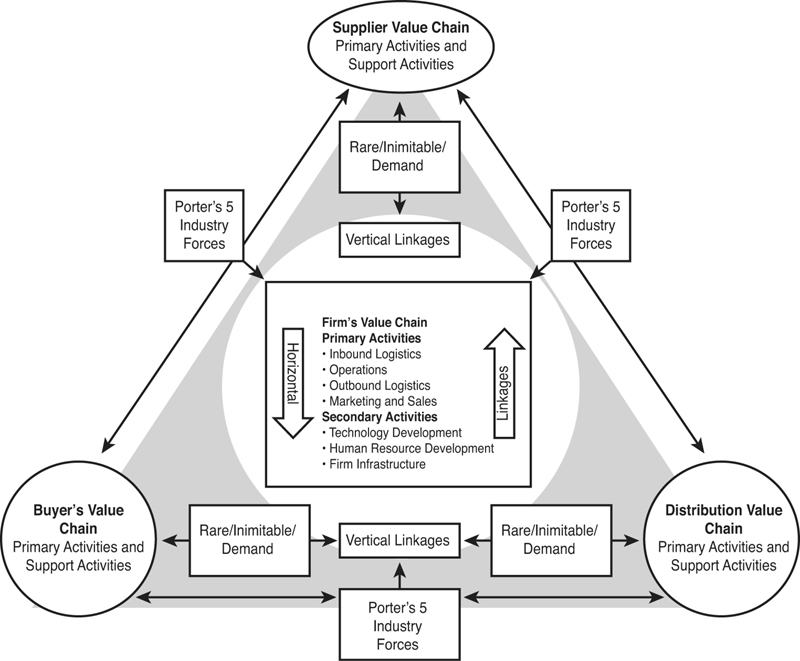

All the suppliers of the company’s inputs as well as forward channel purchasers of the company’s products or services also have their own value chains composed of their primary and support activities. Comprehensive value chain mapping describes interacting and often competing channels and the variety of final markets into which these connect. Collectively, all these value chains comprise the industry value system, as shown in Figure 13.2.

Figure 13.2. Value chains within industry value systems.

The totality of activities in the industry’s entire value system determines the total customer value created. The customers, in deciding what prices they are willing to pay for the products/services produced by the industry, ultimately determine the margins earned by all the participants in the industry value system. The share of industry profit earned by each participant is determined by Porter’s Five Forces, which shape the industry’s structure (see Chapter 7, “Five Forces Industry Analysis”).

VCA is also used to determine how your company can gain a greater share of industry profit. The following list ranks the various types of value chain links in order of their increasing ability to generate competitive advantage:

• Separate individual activities within the company’s value chain. An example is being an industry leader in operations.

• Interlinked primary activities in the company’s value chain. An example is increasing quality inspection, which reduces rework, scrap, and customer returns while increasing customer satisfaction and value.

• Interlinked secondary activities in the company’s value chain. An example is an organizational structure that fosters learning in all the company’s relevant activity areas.

• Vertical links within the industry value system. An example is developing close relationships with suppliers and customers to codevelop low-cost or differentiated strategies for mutual but usually disproportionate benefit that is dependent on each party’s bargaining strength in the larger value system.

Porter recommended VCA to encourage companies to exploit the often-ignored potential vertical synergies that exist between a company’s business units and other participants in the industry value system. The logic of VCA is that most sources of competitive advantage lie in these (often intangible) synergies.

VCA pinpoints opportunities to radically reconfigure industry value systems by eliminating or bypassing entire value chains or major activities within an industry’s value system. A well-known and successful example is Amazon’s innovative use of technology and relationship management to bypass the traditional book retail channel. Amazon has developed close ties with publishing houses and sells solely over the Internet. Dell’s direct-to-consumer model shortened the value chain and reduced the number of players and activities that otherwise would have reduced Dell’s profit margins.

Different secondary applications or subsets of VCA also are used in the pursuit of competitive strategy:

• Competitor analysis. Analyzing competitors’ cost structures, business models, and sources of differentiation is intrinsic to crafting strategy. Weaknesses in rivals’ value chains may allow your business to take action to gain advantages that exploit their inabilities or limitations in delivering to the marketplace.

• Customer value analysis. Incorporating the common thread of customer value-creating activities into the strategy formulation process provides insight that keeps the analysis relevant to this lowest common denominator of profit. Analyzing the value chain helps the analyst spot unnecessary activities, overhead, costs, or redundancies that can be eliminated, thus improving margins.

• Strategic cost management. Expanding cost management from the traditional approaches of universal cost containment and reduction across the company (to incorporate the unique cost drivers for each value activity), as well as combining activity-based accounting with VCA, allow enhanced management of costs. For example, VCA allows the company to identify and then exploit vertical links with suppliers and customers.

• Integration. VCA helps companies invest wisely in vertical or horizontal integration strategies or, conversely, to divest, by understanding the impact of the company’s value chain and its strategic position in the industry’s value system. Many of the economies of scale, strategic fits, and/or synergies that companies hope to gain from mergers or acquisitions become easily identifiable using VCA.

• Supply chain management. Determining the bargaining power of suppliers as well as recognizing their position in the same industry value system potentially generates opportunities for mutually beneficial cooperation between your business and others in the chain.

• Strategic outsourcing. This requires knowledge of the core competencies that VCA can provide. If you understand the company’s core competencies and the relative importance of various activities in the value chain, you can make strategic outsourcing decisions that reduce costs or improve differentiation and flexibility. And you can do so without harming the company’s competitive advantage. The choice of whether to do something internally or to outsource it is one of the key decisions that VCA uniquely supports.

• Acquisitions, mergers, alliances, or joint ventures. Synergy or strategic fit can be advantageously framed by VCA. Target companies can be selected on the basis of how the acquisition would enhance the company’s strength in the industry’s value system. This is done by assessing where along the value chain skill sharing or knowledge transfer can occur between the parties.

• Organizational structure. Drawing the boundaries of organizational units based on discrete value-creating activities and the vertical links of the value chain puts the company more in tune with the key sources of its competitive advantage.

Strengths

From the company’s perspective, VCA is a highly practical tool for understanding its strengths and weaknesses. From an industry perspective, VCA provides a good understanding of the company’s competitive position relative to key customers and suppliers. VCA also helps you understand the nature and sustainability of the company’s resources and capabilities and what new resources and capabilities it might require to be competitive in the future. For those who perform a SWOT analysis as part of their insight development process, VCA provides a much better real-world sense of what is really a strength or a weakness (see Chapter 12, “SWOT Analysis”).

VCA encourages the company to comprehensively review all the activities that deliver value to the customer. It is also more inclusive of the complex economic cost drivers that affect customer value. These include structural drivers (scale, scope, experience, technology, complexity) and executional drivers (management style, total quality management, plant layout, capacity utilization, product configuration, vertical links with suppliers and customers).

VCA also uses both quantitative and qualitative inputs, often helping to develop a better, richer understanding of the transformation process than either of these research types could do alone. The majority of VCA projects benefit by doing qualitative facets first, followed (resources permitting) by a more rigorous quantitative study. If funds and time are short, the ability to focus heavily on qualitative research underlying VCA, including the acquisition and inclusion of secondary data that is freely available from national statistics clearing-houses, still generates a great deal of useful data and information on prices, quantities, and productivity factors.

If your company has adopted activity-based accounting (ABA), VCA is easier, because ABA eliminates many of the distortions of traditional management accounting. In fact, activity-based management (ABM) shares many similarities with VCA. It also works particularly well for companies that already employ ABA, activity-based costing (ABC), competitor benchmarking, Six Sigma, or similar management accounting or statistical control processes. Combined and updated with these sources of data, VCA can generate some of the best empirically-based insights to help you understand exactly where margin is augmented or deteriorated.

Weaknesses

Despite the strengths of VCA, its usefulness is being challenged by the radical changes that information technologies have wrought. A growing school of management thought asserts that traditional value chains oriented around vertical linkages cannot constantly reinvent value at the speed required for successful strategy execution and meeting customer responsiveness demands.

Traditional VCA was developed to help you understand physical assets and flows. It may not be as appropriate to employ for competition based on intellectual assets and services. That being said, newer conceptual developments are happening in the broader scholarship. They increasingly allow for functional modification of the traditional VCA for emerging modes of competitiveness, including value net analysis, value grid analysis, value migration, value constellation analysis, value stream mapping, value shop analysis, and service value chains.

Managing value chains in an information communication and technology environment requires the inclusion of economic realities that are not explicitly addressed by original versions of the VCA model (like Porter’s). VCA treats information as a supporting element in the company’s strategy. At best, it is only part of a secondary activity. Recent models such as the virtual value chain and value web management treat information as a separate and distinct value-creating factor that must be managed separately but together with the enduring physical value chain.

VCA also has been criticized for being too simplistic because many of its qualitative prescriptions are difficult to implement. The most prominent shortcoming is that they require significant amounts of resources. Effective VCA requires a large investment in benchmarking, customer and stakeholder research, competitive analysis, and industry structure analysis, often using data that is not freely or easily available. Conducting VCA might be straightforward in theory, but it is relatively difficult and time-consuming to apply for maximum and relevant effect. This is a key reason why many companies do not choose to exploit it in their ongoing analysis activities.

Furthermore, most of a company’s internal accounting data is incompatible with the analytical dimensions of VCA for several reasons. Traditional management accounting systems rarely, if ever, do the following:

• Collect data related to value-creating activities. Instead, they collect data related to product/service and period costs.

• Collect period costs by product or service, making it difficult to accurately assign overhead costs to value-creating processes.

• Collect data on cost drivers. Departmental budgets are rarely an accurate source for determining the actual cost of value-creating activities.

• Enable transfer prices and arbitrary cost allocation of traditional management accounting systems to appropriately encompass the synergies created by horizontal links in the company’s value chain or the vertical links in the industry’s value system.

How to Do It

Conducting a successful VCA requires judgment, attention to detail, competitive knowledge, and quantitative analysis. Understanding the company’s industry structure and, more importantly, aligning this knowledge with the company’s capabilities, are intrinsic to crafting successful strategies.

The VCA process begins with an internal analysis of the company’s value chain, followed by an external competitive analysis of the industry value system. It concludes by integrating these two analyses to identify and create a strategy that can potentially sustain competitive advantage.

Step 1: Define the Company’s Strategic Business Units

The first level of review draws boundaries around the business’s various segments. This is necessary because the different segments of the business will have different sources of competitive advantage that require different strategies.

Usually, the company’s organizational structure or accounting system does not classify business units in a manner consistent with business unit operations. You must frequently divorce yourself from the usual classifications, such as departments and functions or cost, revenue, and investment centers. This leaves you with two conflicting criteria to define your business units by:

• Autonomy, where managerial decisions about one business unit have little or no impact on the other business unit

• Their ability to support VCA (shared links within the company and between value chains in the value system)

Where these two criteria conflict, it is probably best to choose the latter. A key purpose of VCA is to leverage shared linkages—a strong potential source of competitive advantage.

Step 2: Identify the Company’s Critical Value-Creating Activities

For companies that haven’t adopted ABA, Porter offers several distinctions that define value-creating activities. These companies are those that

• Have different economic structures

• Contribute to a large or growing percentage of total costs

• Contribute to or have a strong probability of contributing to product/service differentiation

The following lists provide suggestions on the nature of questions asked in completing this step.

Assessing the Primary Activities in the Value Chain

Inbound Logistics

What type of inventory control system exists? How well does it work?

How are raw materials handled and warehoused? How efficiently?

How are goods transported? Are they shipped, flown, sent by courier, or sent digitally?

Are our raw materials of high quality, from multiple reliable sources, and priced competitively?

How is material received? From whom? Where is it acquired?

How productive and efficient is our equipment compared to our competitors?

What type of plant layout is used? How efficient is it?

Are production control systems in place to control quality and reduce costs? How efficient and effective are they at doing so?

Are we using the appropriate level of automation in our production processes? Are employees properly trained to use the process? Is it scalable and upgradeable?

Outbound Logistics

Are finished products warehoused efficiently? How much waste do we experience?

How do we manage order processing? What percentage is automated?

Are finished products delivered to customers efficiently? Are our delivery operations appropriate and effective?

Are finished products delivered to customers in a timely fashion?

Marketing and Sales

Is marketing research used effectively to identify customer segments and needs?

Are sales promotions and advertising innovative?

Have alternative distribution channels been evaluated? How do we manage those channels?

How competent is the sales force operation? Is its level of motivation as high as it can be?

Do we present an image of quality to our customers? Do we have a favorable reputation?

How brand-loyal are our customers and our rivals’ customers?

How well do we solicit customer input for product/service improvements?

How promptly and effectively are customer complaints handled?

Are our product warranty and guarantee policies appropriate?

How effectively do we train employees in customer education and service issues?

How well do we install, repair, and provide replacement parts and services?

Assessing the Support Activities in the Value Chain

Firm Infrastructure

Can we identify potential opportunities or threats? Do we have an early warning system?

Does our strategic planning system facilitate the accomplishment of organizational goals?

Can we obtain relatively low-cost funds for capital expenditures and working capital?

Do we have good relationships with all our stakeholders? Which groups need more attention?

Are we being responsible corporate citizens in the communities where we operate?

Human Capital Management

How effective are our procedures for recruiting, selecting, orienting, and training employees?

Are appropriate employee promotion policies in place? Are they used effectively?

Does our work environment minimize absenteeism and result in reasonable turnover?

Are union-organization relations (if applicable) constructive and mutually beneficial?

Are employees empowered with decision-making capabilities as required?

Are levels of employee motivation, job commitment, and job satisfaction acceptable?

Have we developed alternative suppliers for all our necessary resources?

Are resources procured in a timely fashion? At the lowest cost? At acceptable quality levels?

Is purchasing centralized or decentralized? Are we using the structure which is more effective and efficient?

Are our large capital resources procurement policies effective?

Have we established sound, long-term relationships with reliable suppliers?

Systems and Technology

Are our R&D activities successful at developing marketable product innovations?

Do our communication and management information systems support decision-making with timely and accurate reports?

Have technology development activities been meeting deadlines?

What is the quality of our organization’s laboratories and other research facilities?

Does our organizational culture encourage creativity and innovation?

Source: Adapted from Coulter, M.K., Strategic Management in Action, 2nd Ed. (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2002), p. 133–134.

Step 3: Conduct an Internal Cost Analysis

Companies can achieve cost advantages and better margins by either reducing the cost of individual value chain (VC) activities or reconfiguring the VC. Reconfiguration means structural changes such as a new production process, new distribution channels, or a different sales approach such as direct-to-consumer approaches instead of owning retail outlets. An internal cost analysis is composed of the following steps:

1. Assign costs to each critical value-creating activity identified in Step 2. Because costs obtained from traditional accounting reports often are not organized for managerial or cost accounting purposes, they may need to be modified to allocate them properly to the VC activities. Accordingly, a full costing or product life cycle costing approach often can be used that incorporates full capacity utilization.

2. Find the cost drivers for each critical value-creating activity that is driven by more than one major cost category. Structural cost drivers are long-term in nature and affect the economic cost structure of the company’s products and services—items such as scale, scope, learning curves, technology, and complexity. Executional cost drivers are more operational in nature—items such as management style, total quality management, plant layout, capacity utilization, product configuration, and vertical links with suppliers and customers. Controlling these cost drivers better than your rivals generates a competitive cost advantage for your company.

3. Diagnose the company’s current strategy for areas of potential low-cost advantage. Search for horizontal links in the company’s value chain in the form of interlinked value-creating activities that reduce costs by virtue of their symbiosis. This is the time to explore opportunities for cost management. It is important to focus externally to compare the company’s cost structure to its competition through benchmarking and associated practice comparisons. Business process design and reengineering approaches can then be utilized to secure any potential low-cost advantages. For example, FedEx structurally redefined express freight delivery services by obtaining its own airplanes and implementing an efficient hub-and-spoke system.

Figure 13.3 shows how costs are distributed among activities at different stages of a company’s value chain. In this example, the company generates a healthy 25% profit margin. Operations activities are the single largest cost center, accounting for 35% of all costs. Knowing which activities account for the largest proportion of costs and therefore may have greater scope for cost reductions can be a beneficial result of this VCA step.

Figure 13.3. Costs of individual value chain activities and impacts on margin.

Step 4: Conduct an Internal Differentiation Value Advantage Analysis

Differentiation advantages can arise from any segment of the value chain. For example, procurement of unique and scarcely available inputs that rivals cannot access can allow value-adding differentiation of the product to customers, as can effective distribution channels that provide customers with high levels of service quality. Similar to the internal cost analysis, the internal differentiation analysis starts with identifying the company’s value-creating activities and cost drivers. Next, you link your customer and competitive knowledge to the appropriate strategy through the following steps:

1. Conduct customer research to determine a precise definition and understanding of customer value. You can secure this knowledge by speaking with customers and analyzing their value chain to gain insights into how your company’s products and services may provide additional value to them.

2. Identify strategies that can differentiate your company’s products and services. These could include product or service attributes, channel management, customer support, pre- and post-sale support, branding, and price. Based on the company’s core competencies, choose the best differentiation strategy to achieve competitive advantage by offering a product or service that is rare, in demand, and difficult for competitors to imitate.

Table 13.1 describes how you can convert the VCA analysis into value-adding actions with the goal of creating or generating greater differentiation advantages.

Table 13.1. Actions Leveraging Differentiation Advantage from VCA

Step 5: Map the Industry Profit Pool

Define the Parameters of the Industry Profit Pool

The parameters of the industry profit pool depend on the value chain processes that affect the company’s current and future ability to earn profit. It is helpful to assume the perspective of the company, competitors, and customers. Include all the relevant value-creating activities, starting with the purchase of raw-material inputs and ending with the total cost of ownership to the final consumer. Note that the final consumer may not be your company’s purchasers.

Estimate the Total Size of the Industry Profit Pool

Employ several different estimation methodologies to gauge the total size of the profit pool, such as by companies, products, channels, or regions. Usually, accounting profit will suffice for profit. However, when you map an industry’s profit pool with international participants, you can use economic value added (EVA). It eliminates many of the distortions caused by various national generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) regimes. Some sources of information you can use for these estimates are analyst reports, financial statements, security commission reports, and conversations with industry experts.

Estimate the Distribution of the Profit Pool

A good starting point is to use your company’s profit structure by activity (that is, Steps 1 through 4) in the external analysis of rival companies in the industry. Following are a few general rules for this stage:

• Use your knowledge of the underlying economics of your own company to outline each activity’s profit. Take care to segregate allocated costs. This information can be used as a relative gauge to estimate the activity profits of rival companies in the industry.

• Sources of competitive information include financial statements, analyst reports, security exchange commission filings, trade journals, the business press, industry associations, and government regulators.

• A helpful hint is to use the market value or replacement costs of assets that support value-creating activities and the full-costing approach under full capacity for costing the same value-creating activities.

• Use the 80/20 rule. This suggests that 20% of the industry’s companies tend to generate 80% of the industry profit. Therefore, concentrate on the largest companies first.

• The level of analytical detail depends on the degree of vertical integration present in the industry. Start with the focused companies. Then estimate the relevant activity profits of diversified companies by adjusting your knowledge of your own company’s economics and that of the focused companies in the industry. Next, include the smaller companies (the 80% responsible for the remaining 20% of industry profit) based on sampling.

• For accuracy, total the activity profits calculated in this step and compare them to the total industry profit pool calculated in Step 5. If the two estimates are wildly divergent, change the assumptions and tweak the methodology through iteration until the two estimates are reasonably similar.

Figure 13.4 shows an industry profit pool. The results could be surprising in that the activities commanding the largest industry revenue share may receive a disproportionately low share of industry profits.

Figure 13.4. Stylistic industry profit pool.

Step 6: Vertical Linkage Analysis

The opportunities to achieve cost and differentiation advantages within the company’s value chain were reviewed in Steps 1 through 4. Step 5 allowed you to determine whether the company is strategically positioned in the shallow or deep end of the industry’s profit pool. Vertical linkage analysis allows you to seek opportunities to exploit the most important sources of competitive advantage in the industry’s value system. You can combine your intimate knowledge of the company’s economic structure, customer value, and external competitive analysis to determine how to reposition the company into the deep end of the industry profit pool—and keep it there.

The methodology to accomplish this is the crux of vertical linkage analysis. This is also the most difficult stage, because many of the vertical linkages in the industry’s value chain are less tangible and extremely difficult to discover. Nevertheless, it is because of this difficulty that VCA often offers a direct route to competitive advantage. The methodology consists of the following steps:

1. Use Porter’s Five Forces model to determine the industry’s economic structure (see Chapter 7).

2. Determine the cost drivers and core competencies driving the strategies of low cost or differentiation for competitors’ value-creating activities.

3. Evaluate the company’s core competencies—capabilities, skills, and technologies that create low-cost or differentiated customer value. Usually, core competencies are acquired through collective learning and relationships. Identify any opportunities to surpass competing customer offerings by securing missing competencies or supplementing existing competencies needed to successfully craft, maintain, and strengthen a low cost or differentiation strategy.

4. Based on the relative bargaining strength of other value chains in the value system, identify opportunities to acquire or strengthen the required competencies through vertical linkages with suppliers, channels, or buyers in the value system.

5. Avoid the temptation to settle for a mixed strategy—part differentiation and part low cost. This is the easy way, but it does not generate competitive advantage for the average company; rather, it leaves a company wading aimlessly in the shallow end of the industry profit pool. A growing body of academic work, validated by practice, asserts that crafting successful strategy is valuable because of the often-painful trade-offs it forces executives to make. Mixed strategies offer a chance of success only for companies that are pushing the frontier of production possibilities or for those that have a truly integrated global strategy.

6. Identify any potential opportunities for competitive advantage in the vertical linkages between the company’s value chain and the value chains of suppliers, channels, and customers. By co-opting or cooperating with other value chains in the industry’s value system, the company can often craft a low-cost or differentiated strategy that is impossible for competitors to replicate. Complex and fewer or intangible vertical linkages offer the most impenetrable combinations of rarity, demand, and inimitability—the triad underlying competitive advantage.

Step 7: Iteration

Repeat Steps 1 through 6 periodically by making VCA a central component of your company’s competitive intelligence and strategy development system. This helps you proactively manage evolutionary and revolutionary industry change. VCA should be completed at least annually and can show subtle shifts in rivals’ tactics or strategies that you may competitively exploit for optimal impact in most product, company, or industry spaces. This will help you determine how the primary and support activities can work together effectively and efficiently to help your organization achieve healthier margins and sustain competitive advantage.

Case Study: Value Chain Analysis of Walmart Stores

Based in Bentonville, Arkansas, Walmart Stores, Inc. was founded in 1945 by Sam Walton and is now one of the largest retailers worldwide. It operates stores in a variety of formats, such as supermarkets, discount stores, warehouse clubs, and online properties. Its product offerings are wide-ranging: automotive accessories, food and beverages, cosmetics, clothing, and housewares. It also offers a variety of services, including jewelry, pharmaceutical, optical, banking, restaurants, and printing. Walmart provides one-stop shopping for consumers’ overall needs. Its market presence stands at approximately 10,000 retail units in more than two dozen countries.

This case study demonstrates how Walmart’s value chain has contributed to a competitive cost advantage in U.S. retail markets. Walmart’s strategy is to be the low-cost leader among mass merchandisers. It operates on a scale unmatched by any of its competitors. To pursue its strategy, Walmart focuses on using advanced systems and technologies to reduce costs, improving relationships with suppliers by purchasing enormous quantities, and being a tough bargainer. Walmart also aims to enhance customers’ overall store experience. Figure 13.5 shows the relationship between Walmart’s business model and its strategy.

Figure 13.5. The relationship between Walmart’s business model and strategy.

Primary Activities

The following sections discuss how Walmart uses its value chain throughout its primary activities to achieve its strategy.

Inbound and Outbound Logistics

Products from distributors and suppliers are transported to Walmart’s distribution centers via its large truck fleet transportation system. Or, especially where perishables such as groceries are concerned, products are managed by Walmart’s suppliers’ inventory management systems connected directly to the store.

Walmart also uses a technique known as “cross docking” whereby finished goods are taken straight from the supplier’s site, sorted, and delivered directly to the store. This leads to a reduction in the handling and storage of finished goods, resulting in fewer damaged goods and decreased staff needs. The efficiency of this system leads to a form of just-in-time inventory, allowing customers to control the supply of goods they want by their purchases. Essentially, this shifts the supply chain to a “demand chain” led by the “pull” of customers instead of the “push” of the retailer.

Operations

Within the store, operations are activities that allow Walmart to take goods in its distribution centers and quickly convert them into sales to its customers. The process is facilitated by the use of satellite linkages to communicate with all its stores. This ensures that all its stores are rapidly supplied with ample qualities of the fastest-moving products customers are demanding. Walmart has also integrated point of sale (POS), inventory control, radio frequency identification (RFID) tags, and other technologies to reduce costs such as shrinkage and employee theft, accelerate delivery, and improve security.

Walmart’s store formats have long been central to its success, allowing it to maximize its attractiveness to a broad spectrum of customers. Its in-store layout makes for fast movement of product to the shelves and allows easy stocking. Walmart’s stock replenishment process is focused on managing the flow of goods through its stores, using a model it has led the development of—vendor-managed inventories. As Walmart stores sell their goods, sales information flows via computer not only to Walmart’s headquarters, but also to Walmart’s suppliers. They ship replacement merchandise to the stores almost at the rate it moves off the shelves. These activities enable Walmart to achieve higher levels of sales per square foot of floor space in comparison to most of its competitors.

Marketing and Sales

Covering the traditional marketing four P’s of product, place, price, and promotion, Walmart uses these activities to support its low-cost strategy. At Walmart, customers buy products knowing that the store will deliver value in excess of its costs and that Walmart stands behind the goods it sells as a trustworthy merchandiser. In determining where it places stores, Walmart uses a stringent set of criteria to select locations where it will have maximum market impact. Additionally, Walmart applies data mining and proprietary algorithms to determine where products are placed for maximum sales volume within its stores. In regards to price, Walmart has long implemented an everyday low price guarantee, reinforcing its motto of “Save Money. Live Better.” This motto supports its strategy because by guaranteeing the lowest price, Walmart reduces the expense and profit erosion caused by having to run frequent sales to move merchandise. Walmart’s promotional expenditures are much lower than its rivals because it relies heavily on the most effective and least expensive form of marketing—word of mouth.

Services

The central theme of Walmart services is the customer experience. Customers entering a store are met by greeters wearing blue vests who create a welcoming and helpful experience. Throughout the store, price-check scanners allow customers to verify how much they will pay for their goods. Another beneficial service is Walmart’s “no questions asked” return policy. Its “sundown rule” states that employees will do their best to answer customer requests by the close of business on the day they are received. The “10-foot rule” is a customer service policy whereby associates greet nearby customers and ask if they can be of assistance. All these activities reinforce the customer experience Walmart seeks to achieve at the lowest costs.

Support Activities

The following sections discuss how Walmart uses its value chain throughout its secondary activities to achieve its strategy.

Firm Infrastructure

Regular communication flows directly between each individual store and headquarters in Bentonville. Key executives from headquarters are regularly sent to local stores to obtain information about competitors and to learn what is happening in the stores. This unusual practice of cutting out regional levels of dialog creates a close and effective connection between headquarters and local stores. It helps the company quickly respond to changes in customer demand, make corrective actions, and react to rivals’ moves at a store-by-store competition level. These capabilities help add value for the end users by providing products at low prices, meeting customer demand, and resolving any big issues that affect customers’ buying decisions.

Human Capital Management

Walmart has a unique way of linking its human capital management practice with its strategy all along its value chain. Interactions between the company and its associates are based on mutual respect, regular communication, high expectations, and clear incentives. Associates are not paid market-leading wages, thus reinforcing the company’s ability to keep its prices low for customers. But employees are compensated in other ways. They have access to desirable benefits such as profit sharing and health care, retirement, and company stock purchase plans.

Employees have a surprisingly high degree of discretion and autonomy. The company has an open-door policy, and great promotion opportunities create a unique culture unusual in large retail organizations. This adds value throughout Walmart’s chain by sustaining a good working environment for associates and managers.

Unusual but long-standing Saturday morning meetings are the trademark of the company’s management style. This activity creates a unique culture and is believed to help communicate and synergize Walmart’s spirit. This common ritual reinforces a workplace that bonds its associates and creates a motivating sense of belonging.

Procurement

In addition to its centralized megafacility, known as “Vendorville,” in Bentonville, Walmart has developed a small number of highly efficient regional procurement centers. Some of its largest suppliers, such as Proctor & Gamble, have set up satellite offices next to these centers to improve their ability to work with Walmart and manage its inventories while simultaneously reducing transaction and transportation costs.

Walmart requires suppliers to cut their margins and meet its progressive employment policies, although it often assists them in doing so. These practices have enabled Walmart to buy its inputs at the lowest cost, avoid inventory holding costs, and offer lower-priced products that its customers value.

Systems and Technology

Walmart is one of the world’s leading companies in any retail sector at developing and employing ways in which technology, both advanced and simple, can improve its operations. It supports and reinforces its low-cost strategy all along the value chain through its tightly integrated vendor and inventory management systems, to its use of satellite communications to track its truck fleet, to RFID tagging and advanced POS systems for merchandising operations in the store. It also uses low-tech, but highly effective, person-to-person and face-to-face communication practices.