Using Your Mind

In acting, it takes someone with a lot of intelligence to play the part of ignorance. Carroll O'Connor and Jean Stapleton are brilliant people who played Archie and Edith Bunker on TV's All in the Family, a '70s sitcom. Each played ignorance in a special way. But to know all the intricacies of ignorance, a high level of knowledge is required. How would one know what is stupid unless one were smart enough to understand the difference?

Your mind is one of your most powerful assets. As a presenter, you can think on your feet, sway the audience with reason, and persuade people with your logic.

Linking Intention to Content

This sounds more difficult than it is. The fun in this process is using your imagination to create connections between your actions and the supporting elements in your message. In other words, for every major section of information you are sharing with the audience, you need to identify the intention or subtext that goes along with that information. The intention follows the same pattern as the objective. Based on action and described in the form of “to do” something, it isn't a feeling, although a feeling will always arise out of action. It's like a little objective.

For example, let's say your next presentation's overall objective is to persuade the group to take action on a new budget item. At the beginning of the talk, you plan to bring up a comparison to a similar budget decision that was made in the prior year. Stop. What is your inner intention as you go through the comparison? You know you have to persuade, but use your imagination for a moment. How many ways are there to persuade? Probably a million. Pick one.

Let me pick one for you: Show the absurdity in bringing up what happened a year ago. Stress that this is like comparing apples to oranges, and the data from last year is meaningless to this issue.

Let me give you another one: Proclaim the validity of the comparison to last year. Stress that the decision was made by the same management team evaluating the current project, and their track record on these issues is impeccable.

Your intention is different in each case, yet the visual support looks the same. The angle of your approach is going to change, depending on your inner intention.

In other words, you've got a whole bunch of little things to do inside the big thing you have to do. Just like a wedding, there are a million little details, each with an intensity, an action, and an outcome. Then you have to consider the scope of the entire event. Details exist in so many things you do. Why would your presentation be any different? It's attention to detail that will make it successful.

To do this, dissect your presentation into smaller segments and see what is going on in your mind as you cover each segment. If a few charts are displayed in one part of your talk, what is your subtext; what are you really thinking? Is your intention to distract the audience with the details? Is it to drive home the point? Is it to set the stage for the next section of the presentation?

Don't chop the presentation into such tiny segments that you try to find an intention for every moment. This will result in the analysis-into-paralysis problem. Your intentions typically cover a group of visuals. Maybe you'll have six to eight different intentions for a 20-minute talk. You might use an intention more than once for repetitive items such as humor or storytelling. For example, the intention in each of three different stories might be to teach a lesson.

If you just concentrate on the major sections and the related intentions, the tiny moments take care of themselves. They happen as a result of your natural thinking pattern to accomplish tasks. Trust yourself and give yourself more credit. You wouldn't even be reading this book if you didn't have the ability to express yourself and your intentions. You've been doing this all your life. You just have to apply the process to presenting. If you understand the big segments, then the little things under every single moment will become so natural, you won't have to think about them.

Your inner intentions are buried in your brain, and you have to identify them so that you can be sure that the way you offer the information is the way you expect the audience to understand it. This is what I mean by linking intention to content.

Working with Detailed Data

Sometimes your visuals contain detailed information. Typically this happens with data- driven charts (bar, pie, line, area, and so on). Most presenters display these charts for the audience and discuss the obvious items, usually the biggest slice, the tallest bar, the upward moving line—the easy stuff. Although nothing is wrong with this, it adds little value to the audience if they could have figured it out for themselves.

A visual presenter reads between the lines and makes the detailed information come to life. It's a process of identifying the means inside the extremes.

Think of the means as internal causes for the extremes. The extremes are the external data elements that are different enough to force a comparison or a discussion.

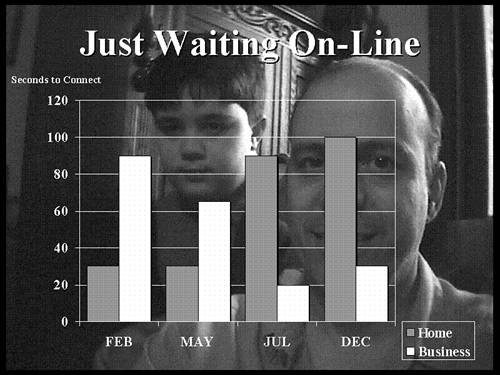

For example, Figure 25.1 is a vertical bar chart. It contains four selected months of data showing the time (in seconds) it takes to connect to the Internet from home and from business. Wait—don't start calling your Internet service provider and complaining. I made these numbers up just for the example.

Figure 25.1. A simple bar chart showing selected months of activity.

Let's say you select one particular set of extremes related to the home group. You might point out that the connect time in February is much faster than in December. You picked two data elements different enough to stimulate a discussion.

Now you have to stress the means of those extremes. You identify the causes of the difference. An obvious one would be a seasonal issue. The reason it takes longer to connect in December is because of the holiday season and the online calls to friends and family. Maybe you dig deeper into the means. You might bring up a recent article you read that mentioned how the home sales of digital cameras seem to peak in mid-November because people want to have holiday pictures in advance of the holiday season. The effect of more digital photos is their transmission in December over the Internet. These photos are much larger files, resulting in more traffic over the Net and, hence, slower connect times. None of this extra stuff appears on the chart—it's all in your head.

Want to try another? Let's use the same example, but pick two other extremes. Compare home to business in the month of July. What are the means inside those extremes? You could point out that more employees take vacations during the month of July than any other time during the year. Not being at the desk in the office results in fewer connections to the Internet, hence less traffic from the business group. However, vacation doesn't always mean travel away from home, and you might mention that with kids home from school, an increase in Internet activity from home results in more traffic on the Net. Maybe you dig deeper into the means. You cite a statistic from the National Education Extension Outreach Foundation that shows a sharp increase in the number of online college-level courses being taken during the summer months when classroom sessions are fewer. The students in these electronic programs are participating from home, which is another reason for the rise of Internet activity in July and the longer connect times from the home group. Once again, the audience gets none of this from the chart on the screen.

By identifying the means inside the extremes whenever possible, you create a lasting impression with the audience. You become the critical bond for the audience between data and description. Without you as that link, anyone could have presented the topic. A visual presenter would never allow that!

Selecting Focal Points

We talked about anchors in the past few chapters. The audience needs anchors and so do you. Anchors don't really move during the presentation—that's why they're called anchors. The anchors are usually big—standing on the left side of the room, five friendly faces in the audience, geometric shapes to help guide the eye—these are all anchors.

But another type of anchor is called a focal point. It's more of a temporary anchor, but it is something you can use at various times during the presentation. Many of the focal points you'll use are less apparent, if at all, to the audience. Focal points are visible fixed objects that help you target your attention as you speak.

Have you ever just stared off into space while you were thinking about something? You probably weren't always looking at the night sky when you zoned out. You might have been at your desk or at home and you were looking at something, but you were not focused on the attributes of the object. You were busy thinking. The best example of this is talking on the telephone. Next time you see someone talking on the phone, watch how many places he looks when talking, almost none of which are required for continuing the conversation. You do this a lot yourself. Your focal points change and vary, depending on what your brain is doing.

As a presenter, you need to be aware of these temporary anchors and use them to your advantage.

You can use two kinds of focal points: primary and secondary. Primary focal points include the screen, the display equipment, and the audience. Secondary focal points include the floor, the ceiling, the walls, the furniture, the fixtures, the exit sign, and any other decorative or noticeable objects you might glance at during the presentation.

Primary focal points are referenced a lot in the presentation, and you'll find yourself gesturing to them and interacting with them constantly. Primary focal points help you concentrate your attention, and they are very apparent to the audience.

Secondary focal points are less obvious to the audience. However, they also help connect your thoughts to physical objects in order for your delivery of information to appear more natural.

You can't stare off into oblivion or space out during the presentation, even though you do it in real life. But the very act of staring can be so effective for the audience because they can see you thinking, pondering, and struggling to make information important. Without an object to focus attention on, you can't show the audience that you're thinking. Focal points make thinking a reality.

For example, suppose you're presenting in front of a group of 40 people. You're getting ready to start, and you take note of several objects in the room that catch your attention. On the back wall is a painting of a snow-covered mountain. On the ceiling is a row of track lighting with spotlights facing the sidewall. On the other sidewall is a thermostat and, next to it, a wall telephone. All of these are usable secondary focal points.

Let's say that during the presentation you are telling of a work-related experience in which you had to lead a team of people to accomplish a task. During the story you are reflecting about the experience, and your eyes glance to the painting on the back wall. It only takes a few seconds of your attention on that painting to give the impression to the audience that you are reflecting on the experience. They see you staring into space and believe you are explaining to them what you see in your mind's eye. Without an object to focus on, you might recount the story too quickly and lose some of the impact. The painting gives you a visible focal point that helps demonstrate your thoughts and makes the telling of the story look more natural.

You can't just look off into space; you need something to look at, such as the painting. Because you looked at it prior to the presentation, you are not distracted by the details in the painting. That's why you glance around the room before you begin the presentation. You have to know your focal points in advance. You don't want to be surprised by anything you glance at while speaking.

Sometimes the attributes of a focal point can help in your description. Let's use the same example. It's later in the presentation. You're displaying a line chart and commenting on the rising costs of a current project. You glance at the thermostat briefly and you describe the skyrocketing costs as reaching the boiling point, ready to burst. The thermostat as a focal point created a heat-related image in your mind, helping you build a better description for the problem.

Focal points are extremely useful, and the more you can selectively use these temporary anchors, the easier it is to show the audience what you're thinking.

Using Virtual Space

Just as focal points help you connect your thoughts to visible objects, virtual space helps you connect the audience to invisible objects. You use virtual space to show the audience how your mind is visualizing the concepts you're explaining.

At times during a presentation, you will mention several related concepts to the audience and not really know if the group is following along. You already see the concepts in your mind, but the audience has no idea how to distinguish them.

For example, you mention to the group that three separate departments will be involved in a decision: marketing, sales, and finance. The instant you name the three groups, you have a visual image in your head of each of those departments. You can see where in the building the departments are, you see the faces of people who work in each area, and you are visualizing three distinctly unique departments.

Now you have to get the audience to see three different departments. You do this with virtual space. You physically place the departments in the air for the audience to reference. As you say “marketing,” your right hand places the word in the air to your right. As you say “sales,” your left hand places the word in the air to your left; as you say “finance,” you place the word in the air in front of you, using both hands. In all three moves, your palms would open out to the audience without blocking your face.

The point is that the three departments are floating in virtual space, and you can immediately reference any of the three by physically retrieving it from its floating position. If you say, “The marketing department is going to…,” you can gesture to the space occupied by the word marketing, to your right, where you placed it. If instead you use the space to your left, the audience would say, “No, no—that's the sales department over there!” The audience remembers where you placed the references because they have been given focal points. The concepts are floating in virtual space for the audience to see.

Use virtual space to identify concepts as separate and distinct from one another. Don't just use virtual space and then do nothing with the floating anchors you handed the audience. When you place the items in the air for the audience, immediately reference one of them to begin noting the distinction.

Other ways of using virtual space include showing timelines and distance. For example, if you are describing several events from 1990 through the present, you might use your right hand to place 1990 in the air as the beginning of the timeline. Then use your left hand to stretch an invisible thread from your right hand to a place in the air to your left to show the length of the timeline. For showing distance, you might gesture with your left arm fully extended to a point at the far corner of the room while you mention an office location in another state. The group would realize you are referencing a place in the distance and not somewhere nearby.

Keep in mind that the moment you change physical space, virtual space falls to the floor and disappears. For example, suppose you're in the front of the triangle and you use virtual space to distinguish three items. You reference one item, but then you navigate to the middle of the triangle. Because you moved to another physical space on the floor, the virtual references disappear. Those little anchors or focal points for the audience can't float in space if your body is not around to support them. This means that whenever you move in the triangle, you get another opportunity to use virtual space.

Handling Distractions

When I talked about the mechanics of form in the previous chapter, I mentioned some body and voice problems that the audience might find distracting. Sometimes it's the other way around, and you can get distracted while presenting. With almost every distraction, the result is a loss of concentration. Your mind loses focus on the objective in the presentation. You usually get sidetracked because you were not prepared for the diversion. The following sections discuss some of the external forces at work that might challenge your attention to the message.

The Slacker

Activity in the audience is a very common distraction for a presenter, and this usually happens at the beginning of a presentation. It's called tardiness. A latecomer can cause a break in the flow for you while you speak. This is more apparent as the tardy person takes a seat closer to the front because more people have to watch the person get settled.

The best way to handle the distractions caused by someone who arrives late is by finding a way to repeat or recap as much of the story necessary for the person to catch up. The one who is late might be critical to your plan. The tardy person might be the one making the final decision. You never know what role the latecomer plays. Don't chance alienation. Bring that lost sheep back into the fold.

In addition, the distraction of a latecomer usually messes up your current point. Because you'll have to repeat what you just covered for everyone else's benefit, you can sneak in a quick sentence to recap for the slacker.

The Attacker

Sometimes a hostile audience member can distract you. Hostility in the audience usually relates to the content in some way. It's simple: You counter hostility with friendliness.

Sometimes political or market forces are at work, causing frustration for some people, and reactions are negative. I've seen this hostility at employee meetings right after a downsizing took place. It happens at shareholder meetings if profits have taken a hit.

If you are faced with hostility, agree with your adversary as quickly as you can. Then, look at the source of the conflict and ask yourself, “Can I fix this?” Be honest. If you can address the issue, do it. If you can't, then try turning it around. Ask the person, “Do you have a suggestion?” The key to this is that your attempt to solve or ask for help in solving a problem is viewed as a friendly way of working with your adversary.

You usually can't win if you fight back in a public forum. The reason is that the audience believes you know more than you reveal, and fighting back suggests you don't have an answer or will not admit to being wrong. That's why agreement helps soften the blow. I realize this approach can't cover every hostile situation, but it works in most cases.

The Know-It-All

Another distraction is caused by the ego of the know-it-all. Counter the conceit with fellowship. The know-it-all appears more often in small group presentations because the chance to speak out is more readily available. Regardless of the venue, the know-it-all can cause you to lose your concentration.

Like the attacker, you need to side with the know-it-all right away (if possible). For example, suppose you are discussing the tax benefits of a new copy machine for a client. In the meeting is a person from the client's accounting department. We'll call him “Zeno.” Now Zeno pipes up very early in your talk and says, “Are you considering this a Section 1231 asset for depreciation purposes?” The rest of the group rolls their eyes, having seen Zeno openly destroy others in the past. No one escapes his wrath. If you are discussing tax benefits, you already understand enough about accounting to handle Zeno easily. You address his concerns and respond with enough information to satisfy his hunger. Still, you also know this is only the beginning. Zeno lives for these moments.

This is when you form the Fellowship of Accountants, in which you and Zeno are the charter members. Soon after responding to Zeno, at the very next accounting issue, you look right over to Zeno and say, “and as Zeno can tell each of you, the equipment.” In other words, you make an ally. Zeno becomes your constant resident expert to support nearly every financial point that sounds even remotely confusing.

By making that person your support for complex issues, you always have a very effective way to neutralize the smart-aleck. If you fight the know-it-all, you may gain some sympathy from the rest of the group, but you'll be diverted from your topic and end up being less effective with your message.

The Talker

This is the person who distracts by talking during your talk. Usually, talkers travel in pairs, unless they're crazy. So how do you handle people talking when you're talking?

You do nothing. That's right, nothing. Believe it or not, the audience handles them for you. Try this. Go to a movie with a friend. Start talking with your friend. It won't take long before someone whirls around and shushes you. In a play, a ballet, or an opera—anywhere people pay money—fear not, they will quiet the talkers.

People pay to attend a meeting. It's their time, and time is money. Trust the crowd to help you out on this one because the talkers not only disrupt the speaker, they distract the listener, too.

The Boss

Of all the distractions in the world, the boss's presence can stop a presenter cold. How do you deal with a superior in the crowd? You usually freak out. The reason is that your effort to impress becomes greater, and you simply try too hard. In the theater it's called overacting, and it usually happens when the actor knows a critic is in the audience.

You may find yourself making more eye contact and directing more of the information to your boss at the expense of the rest of the audience. This is a big mistake because you lose on two counts. First, the audience is slighted from your true attention, and second, your boss may feel singled out during every moment. This is frustrating. When a presenter pays a lot of attention to one person, that person feels obligated to listen even more attentively, almost out of courtesy.

The solution to presenting to a superior is to treat that person the same as all the others in the room. Don't pay any more or any less attention than to anyone else. If you deliver the talk with sincerity and you follow the objective through to the call to action, the presence of your boss will have gone unnoticed. The key here is to neutralize the superiority with equality.

The distractions you might face can break your concentration if you are not prepared to handle the diversion. Typically, you don't fight fire with fire in these cases. You usually play to counter or neutralize the offender. If you stay focused, you remain in control of the presentation, and you hold the attention of your audience as you deliver the message.