7. Financial Engineers and Their Creations

The Italians make designer sunglasses, the Japanese manufacture precision vehicles, Russian vodka has no comparison, and until the subprime financial shock, everyone wanted some of America’s financial ingenuity. It was thought to be our comparative advantage. The efficiency of the U.S. financial system was the envy of the world; it could take the nation’s paltry savings and direct it to financing investments that reaped big returns. Why save 50% of your income—as they do in China—or even 10%, as the Germans do, if you could put aside close to nothing and get the same returns or better simply by making the right kind of investments? The U.S. financial system was better at this than anyone; the wizardry of America’s financial engineers seemed unparalleled.

Despite the complexity of the American financial system, its basic function is quite simple: Lend what we save to others who can do something productive with it. In times past, this was done entirely by banks.1 Making a loan was very straightforward. A bank took cash from depositors and lent it to a household or business. The bank paid the depositor some interest and made a profit by charging a little more in interest from the borrower. The bank owned the loan until it was repaid and took the loss if the borrower fell into unhappy circumstances and defaulted. Because the banks’ deposits were insured by the government, regulators required them to hold some cash—capital—aside in case too many borrowers defaulted. Regulators also monitored the banks’ lending to make sure it was prudent; if a bank made too many bad loans, it could fail, putting the government on the hook to repay depositors’ money.

The banks lost their tight grip on the financial system beginning in the 1970s and 1980s. These were tough times for banking; volatile inflation and high interest rates made it difficult to make a profit.2 The high rates crimped lending and sent deposits fleeing to newly established money market funds, which offered higher returns to savers. Many banks also stumbled badly in the early 1980s by lending too aggressively to Latin American nations who mismanaged their debts and ultimately defaulted on billions.3 The collapse of the savings and loan (S&L) industry was even more devastating, with more than 1,000 institutions failing between the mid-1980s and early 1990s. The massive financial debacle left regulators to sort out hundreds of billions of dollars of loans from the defunct S&Ls.

The vicissitudes of financial markets and the financial chicanery of unscrupulous S&L owners created the S&L mess, and eventually high finance resolved it. The Resolution Trust Corporation (RTC), established by policymakers to dispose of the S&L’s assets, gracefully employed a financial technique known as securitization. In a securitization, loans are combined or pooled, and their collective interest and principal payments are used to back a tradable security that is sold to investors. As a group, the investors become owners of the loans and are entitled to receive its interest and principal payments. The RTC securitized everything from auto loans to commercial mortgages, sold them to investors, and resolved the S&L crisis at a surprisingly low cost to taxpayers.4

Securitization wasn’t born at the RTC—that honor goes to mortgage lenders Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and the FHA in the 1970s—but the RTC demonstrated that the technique could be used commercially for all types of loans. The RTC also helped create the legal and accounting rules necessary for securitization to work, as well as the trading infrastructure needed for investors to buy and sell the securities. As the RTC wound down its operations in the mid-1990s, Wall Street happily took the wheel of the securitization machine.

Investment bankers first applied securitization to the mass market via credit cards. Using borrowers’ credit scores and targeted direct-marketing techniques, banks had already figured out how to put cards in the hands of millions of average-income or even low-income households. The only limit on the banks’ growth in this area came from their own balance sheets—banks lacked sufficient deposits or capital to grow freely. Securitization lifted both constraints. When a credit card was securitized, banks didn’t need deposits; the investors buying the credit card–backed securities provided the money. Capital wasn’t an issue, either, because the investors—not the card-issuing banks—owned the loans. Credit card lending soared, with receivables doubling in the mid-1990s.

Securitization also powered a boom in home equity and manufactured housing lending. Second-mortgage loans had received a big lift in the late 1980s, when Congress eliminated the tax deductibility of interest payments on nonmortgage debt.5 Interest on a home equity line of credit was still deductible, however, giving homeowners a cheap and easy way of borrowing against their houses. Manufactured homes took off as house prices rose, making it harder for prospective first-time home buyers to come up with down payments on traditional dwellings. Creative marketing also made manufactured homes seem attractive alternatives to apartment living. The number of outstanding home-equity and manufactured-home loans almost tripled during the mid-1990s.

Many of the most active credit card, home equity, and manufactured-housing lenders were not banks at all, but finance companies. These institutions didn’t collect deposits—they didn’t need to because the loans they originated were securitized. And since they didn’t collect deposits, finance companies weren’t subject to the same regulatory oversight as banks. Taxpayers weren’t on the hook if they went belly up—only their shareholders and other creditors were. Finance companies thus had little to discourage them from growing as aggressively as possible, even if that meant lowering or winking at traditional lending standards.

The banks’ long-standing “originate-to-hold” model of lending, in which they kept the loans they made on their own balance sheets, was rapidly giving way to a new “originate-to-distribute” model, in which loans were securitized and sold to a wide array of investors. This change in the banking business model was roundly endorsed by regulators. Because banks didn’t own the loans, they didn’t bear the risk, diminishing the odds of another S&L-type crisis. Regulators felt anything banks could get off their balance sheet was fine by them. Of course, the risk involved in making these loans didn’t go away; it simply shifted to investors and, by extension, to the broader financial system.

What happened next should have sounded an alarm about the limitations of securitization. Delinquencies, defaults, and personal bankruptcies ballooned, as households that shouldn’t have gotten a credit card or home equity line in the first place ran into trouble. The securities backed by these loans were also hit hard and contributed to the global financial crises of 1997–98. That episode began among the indebted economies of Southeast Asia, extended to Russia (which defaulted on its debt), and ended with the collapse of hedge fund Long Term Capital Management. Less remembered is the freezing up of the asset-backed securities market, in which credit card, home equity, and manufactured-housing securities were traded. For several days during the fall of 1998, no trading at all took place in these markets. The panic was quickly quelled when the Federal Reserve slashed interest rates and Fannie and Freddie stepped in to buy a lot of mortgage securities, providing much-needed liquidity to the markets. But it wasn’t enough for many finance companies, which either failed or were acquired—in many cases, by banks. The dollar amounts involved in that crisis were dwarfed a decade later by the subprime financial shock, but much of what happened later seemed all too familiar.

Securitization Dissected

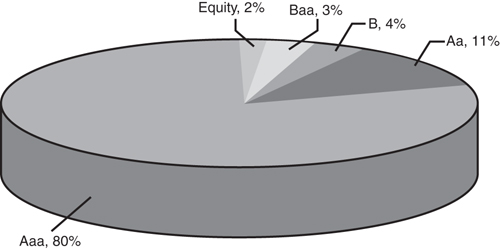

At bottom, securitization is not very complicated. The interest and principal payments paid on the pooled loans are paid to investors in a specific order, which is spelled out by the securities’ tranches—French for “slices.” Those investors who are particularly averse to risk buy the tranches viewed as most secure by the credit-rating agencies. Investors in these senior tranches get paid first, before all other investors. To add more protection, a pot of money from the loan payments is set aside just in case a large number of borrowers default.6 The tradeoff for all this protection is a lower return—investors in senior tranches receive lower rates of interest on their investment. Senior tranches make up the bulk of most securitizations; in the average residential mortgage-backed security (RMBS), for example, senior tranches account for 80% of the face value—also called the capital structure—of the security (see Figure 7.1).

Figure 7.1 Most mortgage securities are mostly Aaa: capital structure of a typical mortgage security.

After senior investors get their money, investors in the middle-rated or mezzanine tranches receive theirs. Investors in these tranches are assured of payment under most circumstances, but if the economy suffers a recession or housing experiences a cyclical downturn, things could get dicey, and mezzanine investors might not get all their money back. Mezzanine tranches account for 18% of the average security’s capital structure.

The remaining 2% is the riskiest slice of the security, known as the equity tranche. This portion isn’t even rated by the credit-rating agencies. Investors in the equity tranche are the last to be paid, and thus may not get all their money back if too many borrowers default. Because of the obviously high risks, the returns can be large if all goes well.

Wall Street’s securitization machine went into overdrive during the housing boom, producing a frenzy in the mortgage securities market. At its peak in 2005, more than $1.1 trillion in RMBS was issued and sold to investors. Another $1 trillion was sold in 2006. In the first half of 2007, leading up to the subprime financial shock of that summer, RMBS sales came in not far off the $1 trillion mark.

For any securitization to succeed, investors must be willing to buy each of the tranches. Banks themselves were first in line, picking up most of the senior-rated segments. Returns on these were low, but greater than the banks were paying to their own depositors. Just as important, regulators required banks to hold very little capital in reserve against the chance these high-rated securities would default. The high rating meant there was very little risk—or so regulators thought. Insurance companies and various types of asset managers bought the bulk of the mezzanine tranches. These firms were searching for higher returns than the senior tranches offered, and they didn’t have the same regulatory constraints as the banks. Besides, the mezzanine pieces were still A-rated securities, and the chance of default was thought to be relatively low. The biggest buyers of the equity tranches were hedge funds. The managers of these investment pools knew they were taking bigger risks, but their clients demanded extraordinary returns, which are tough to generate without substantial risk and lots of leverage (borrowed money).

Financial Alphabet Soup

Securitization didn’t stop with plain-vanilla RMBS. Instead, it evolved into a dizzying, mind-numbing alphabet soup of financial products. The most notorious was called a collateralized debt obligation (CDO). This was essentially just a mutual fund for bonds and loans. Like a stock mutual fund, which holds stocks from many different companies, a CDO buys bonds; these can be straight-up corporate bonds, or securitizations backed by mortgage loans, credit cards, auto loans, and so on. One key benefit of stock mutual funds is diversification; they enable investors to avoid the risk of keeping too many eggs in one basket. In theory, the same benefit applies to a CDO. If the CDO invests in a wide enough variety of bonds, it should be less risky.7

The CDO’s lineage can be traced back to the late 1980s, but it came into its own in the early 2000s.8 CDOs were backed initially by investment-grade corporate loans and bonds and were particularly attractive in the wake of the tech-stock bust, when businesses had to offer high interest rates to attract nervous investors to buy their debt. CDO managers could make good money by simply collecting these interest and principal payments, passing most of it along to CDO investors and keeping a cut for themselves.

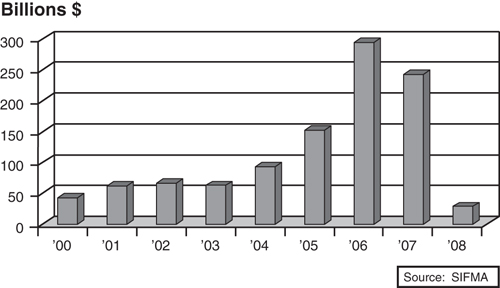

But this simple scheme became increasingly difficult as the economy improved; financial pressure on firms receded, as did bankruptcies, and corporate bond yields declined. CDO originators—mostly investment banks—quickly focused their attention on higher-yielding credit card–and auto loan–backed securities, and ultimately on mortgage securities, including those backed by subprime loans. The product they created was referred to as an ABS CDO (because “asset-backed security collateralized debt obligation” was quite a mouthful), and it exploded onto financial markets. ABS CDO issuance soared from virtually nothing in at the start of the 2000s to nearly $300 billion at its peak in 2006 (see Figure 7.2).

Figure 7.2 CDO issuance soars in housing boom: ABS CDO issuance.

ABS CDOs were overwhelmingly popular; they seemed to offer a win-win proposition for everyone. Investors liked CDOs for their high returns, apparent diversification benefits, and capability to precisely calibrate the risk they were taking on. CDOs have the same tranching structure as traditional securitization, with payments going first to senior tranches and then mezzanine tranches, and an equity tranche that shouldered the most risk. CDO managers collected fat fees that were especially attractive if the CDO allowed for active management of the securities in the CDO. Managers could buy and sell securities out of the CDO to enhance its return or lower its risk. CDO originators also earned lucrative fees and solved one of their biggest problems in putting together a securitization: finding enough investors for all the tranches. At times, depending on market conditions, investors weren’t quite as interested in one of the tranches. Mezzanine tranches, in particular, could be a tough sell. Most investors wanted either the safety of a senior tranche or the high return of the equity tranche, not the stuff in the middle. So-called mezzanine CDOs were created from the mezzanine tranches of traditional securitizations, tranching them up further and creating more of the better-liked senior and equity tranches, but now within a CDO.

If that wasn’t confusing enough, it became even more tangled. CDOs were created from tranches of other CDOs. These were called “CDOs-squared” or “CDOs of CDOs.” And as the securitization machine spun out of control just prior to the subprime shock, CDOs-of-CDOs-of-CDOs—or “CDOs-cubed”—were being manufactured. There were also synthetic CDOs, as opposed to “real” ones. With most asset-backed securities, including subprime mortgage securities already accounted for in CDOs, originators needed to cook up something else, lest the market cool off. A synthetic CDO did not buy tranches of securitized loans or even tranches of other CDOs; it bought credit default swaps (CDS).9 A CDS is an insurance contract on a bond or loan in which one party pays the other an insurance premium and expects to be compensated in return if there is a default. Most credit default swaps are written on corporate bonds, but plenty of CDS are also written on residential mortgage securities. With the notional value of CDS—the face value of the bonds being insured—totaling in the tens of trillions of dollars, there seemed to be no limit to what the securitization machine could produce.

Shadow Banking System

By the time the subprime financial shock hit in summer 2007, the machine was tranching and distributing trillions of dollars in securities to investors across the globe. Securitization’s financial web was expanding exponentially, as was its dizzying complexity. Yet policymakers thought this was precisely securitization’s most significant strength. The risks involved in making a loan were no longer concentrated within any one financial institution; rather, they were spread across the entire global financial system. Loan defaults were less likely to jeopardize the viability of any particular institution, as their financial pain would be diffused widely among many investors and institutions.

Global banking regulators encouraged banks to securitize their loans, pushing the risks off their balance sheets. This attitude was codified in a series of agreements known as the Basel Accords, named for the Swiss city in which they were first hammered out.10 The most recent of these agreements, called Basel II, imposes global rules on banks regarding the amount of capital they must hold in reserve to cover loan or investment losses. These capital requirements vary based on the expected risk of the investment—if a bank holds relatively safe government bonds, for example, it is required to hold less capital to guard against loss. This is called risk-weighting, and it makes sense as long as the rules reflect the true risks of a particular asset or investment. For years, highly rated residential mortgage-backed securities, collateralized debt obligations, and similar securities were assigned relatively low-risk weights, and regulators thought they were safe.

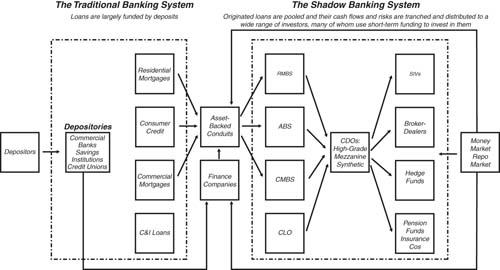

Banks thus had a strong incentive to avoid making and keeping mortgages and other loans, and to hold mortgage-backed securities instead. Banks were happy to originate loans—processing borrowers and accepting origination fees—but less interested in actually funding the loans, which required them to hold more capital in reserve. Funding for loans thus came increasingly from nonbank institutions. These institutions were a mixed bag; they included investment banks, hedge funds, money market funds, and finance companies, as well as newly invented entities called “asset-backed conduits” and “structured investment vehicles” (see Figure 7.3). Together they formed a shadow banking system, which was subject to little regulatory oversight and also not required to publicly disclose much, if anything, about itself. By the second quarter of 2007, just prior to the financial shock, the shadow banking system provided an astounding $6 trillion in credit and was rapidly closing in on that provided by traditional banks.

Figure 7.3 The global financial system.

It was clear that the banks had off-loaded a substantial amount of risk to the shadow banking system, but it was not at all clear which institutions in this opaque galaxy were bearing those risks—or exactly how large those risks were. Policymakers took comfort in the notion that risk seemed to be spread widely around the globe and thought that any problem in the shadow banking system wasn’t theirs to worry about. Unfortunately, the system didn’t work the way they thought.

Liquidity Evaporates

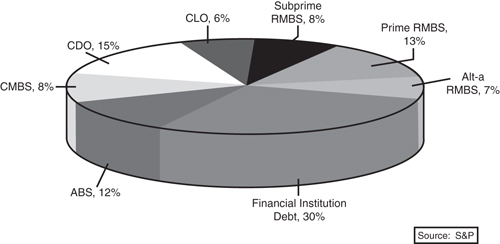

Take the structured investment vehicles (SIVs), for example. Many big global banks established these to make big bets on securitized loans. At their peak in mid-2007, SIVs held $1.4 trillion in subprime RMBS and CDOs (see Figure 7.4). Banks generated handsome profits from their SIVs, earning fees for creating and managing them. Making them particularly attractive, SIVs could be structured so that their investments didn’t sit on the banks’ balance sheets; thus, banks faced no requirement to hold capital to protect against the SIVs’ risks.

Figure 7.4 What SIVs invest in: SIV share of investments, October 2007.

SIVs took substantial risks, starting with their habit of selling short-term commercial paper—IOUs that came due within a few days or weeks—to finance investments that would mature over much longer periods of time. In banker-speak, they were borrowing short and lending long, much like those doomed S&Ls of the 1980s that were taking deposits on which they had to pay prevailing market rates or risk losing them to finance 30-year mortgage loans. It was a profitable practice as long as money market funds and others were willing to buy the SIVs’ commercial paper. It quickly unraveled when the subprime financial shock caused the SIVs’ investments to go sour. Money markets began shunning SIVs’ commercial paper, fearing they would never be paid back. In response, the SIVs turned back to the banks that had created them. Most SIVs had credit lines with their parent organizations, set up to tide them over any short-term need for cash. The banks had been happy to set these up, using them to collect additional fees, and had never thought they would really be needed. Now the SIVs were desperate for cash.

At one point in late 2007, it seemed that nearly all SIVs were about to fail, creating a huge forced fire sale of their investments. Such a sale would have meant plunging prices and a much bigger financial shock. Alarmed, the U.S. Treasury Department intervened, brokering a deal among major banks to try to keep this from happening.11 The deal was never implemented; the SIV-owning big banks chose to resolve their problems individually. Yet as the SIVs’ investments flowed back onto the banks’ own balance sheets, it became clear that the shadow banking system hadn’t spread risk as widely as had been thought. The regulators, moreover, were still on the hook if something went wrong.

Similar short-term funding issues also threatened the asset-backed conduits. Like SIVs, these financial vehicles had been created by big global banks to hold loans that the banks had originated for securitization. The conduits were like warehouses, where loans could reside until they were pooled into securities. Because the banks never technically owned the loans, they were not required to hold any capital against them. In early 2007, some $400 billion worth of loans sat in such warehouses. Like the SIVs, these were funded with short-term commercial paper—and like the SIVs, by summer 2007, the conduits could no longer sell their commercial paper because the money funds and other investors feared they would never be repaid. As the conduits were forced out of business, the securitization machine ground to a halt.

Leverage Kills

The shadow banking system also amplified risk through leverage. Hedge fund managers were particularly aggressive about investing with borrowed money, even when their investments included the riskiest equity tranches of securitizations. At the peak of the financial frenzy in 2005–2006, many hedge funds were leveraging such investments as much as 15 times—that is, for every dollar of their own money they invested, they borrowed $15. The hedge funds had promised to deliver supersized returns, and these could only be generated by taking large risks with lots of leverage.

Leverage can indeed turbocharge returns when investors bet right, but it can be financially cataclysmic if they bet wrong. Take the case of a hedge fund buying a subprime mortgage security worth $100. The fund puts down $10 of its own money and $90 that it borrowed. If the price of the security rises 10%, the fund’s return is 100%—it has doubled its original $10. But if the security’s price falls 10%, the fund’s equity is wiped out. At that point, either it can put up more of its own money, replenishing its equity, or it will lose the investment to whoever loaned it the $90—just like a homeowner who gets foreclosed.

Unlike many ordinary homeowners, however, hedge funds were supposed to be sophisticated about risk. They hedged—hence the name—which made them bolder about taking on risk and leverage. They hedged against the risk that an investment’s value would fall by making another investment they thought would rise in value in such a circumstance. One popular hedging technique was to balance investments in subprime mortgage securities by short-selling the ABX index.12 Shorting is a bet that the value of what is being shorted will fall. Like the Dow Jones Industrial Average or the NASDAQ, the ABX index condenses a lot of market trading into a single number; the trading it tracks reflects the price of credit-default swaps—sophisticated insurance contracts—on subprime securities. When worries about mortgage defaults rise, the cost of insuring against a default on these securities rises and the ABX falls. Long before the subprime financial shock hit, it was evident that conditions were deteriorating because the ABX was falling. Those who shorted the ABX—thus betting it would fall—were making money even as prices for subprime securities were also falling. If, like the hedge funds, they were also buying subprime securities, they were thus at least partially covering their own losses.

Yet investing with leverage can be lethal, even when combined with hedges. This was demonstrated by the implosion of two prominent Bear Stearns hedge funds in July 2007,13 arguably the proximate catalyst for the subprime financial shock. The hedge funds had invested in CDOs of Aaa-rated subprime mortgage securities. Their investments had been highly leveraged, but to hedge at least some of the risk, the funds used the ABX index. It seemed like a winning formula: Factoring in interest received on the CDOs with the cost of the debt to purchase them and the cost of the credit insurance to hedge them, the funds ended up with a hefty positive rate of return—“positive carry,” in hedge fund lingo. Yet it all went badly awry as surging mortgage delinquencies rapidly undermined the price of the funds’ subprime securities. The fund managers had not hedged enough to cover their leverage-enlarged losses. The banks that had loaned money to the funds grew nervous as their collateral—the subprime bonds—evaporated. The banks demanded the Bear funds put up more collateral, forcing them to sell their bonds to raise cash. That selling made prices for subprime bonds fall even faster, making the banks even more nervous and sparking more demands for collateral, which caused more selling. It didn’t take long before the Bear hedge funds were wiped out.

Diversification Disintegrates

Regulators were much too confident that diversification would protect the new-fangled securitizations being distributed throughout the shadow banking system. CDOs, in particular, were supposed to benefit from diversification, by combining securities that weren’t alike. If one of the securities in a CDO performed poorly, it would be offset by another, better-performing component in the CDO soup.14 CDO managers were paid handsomely for their presumed ability to mix securities just right and produce a well-diversified CDO.

CDOs of corporate bonds were able to achieve diversity by including bonds from companies in different industries. Combining bonds from Delta Airlines with ExxonMobil, for instance, was one way to protect a CDO from the impact of big spikes in oil prices. As Delta is hurt by surging fuel costs, Exxon’s bonds are soaring for the same reason. Similarly, combining bonds from a home builder with those of a healthcare provider helps cushion investors in a downturn; as builders struggle to raise cash, healthcare remains largely unaffected.

CDOs of mortgage securities were supposed to achieve diversity by mixing mortgage securities from different parts of the country. In the past, housing downturns were relatively concentrated; house prices can fall in Los Angeles, Houston, or Boston, but never in too many places all at once (the Great Depression aside). Because a CDO effectively combined mortgages from all over the country, it seemed a good, safe way to invest in housing.

CDO issuers, managers, and investors largely dismissed the idea that a downturn could affect more than a few overvalued local markets; they failed to recognize that they were in a national housing bubble. When prices started falling and homeowners stopped paying on their mortgages nearly everywhere, it quickly became clear that the CDO had not diversified risk at all—it had concentrated risk in a highly leveraged investment.

Who’s Responsible?

Of all the places you can point the finger for the housing bubble and subprime financial shock, perhaps the most deserving is the removal of responsibility from the financial system. Lost in the rapid, wholesale rush to securitization and the shadow banking system was the notion that someone—anyone—should ensure that individual loans are made responsibly, to responsible borrowers. A bank that makes and holds a loan has a clear incentive to be responsible and guard against excess because its own bottom line will suffer if it isn’t repaid. Government regulators also have a responsibility to make sure that banks are lending prudently because taxpayers will pay if they don’t.

Securitization undermined this incentive for responsibility. No one had enough financial skin in the performance of any single loan to care whether it was good. A shaky mortgage would be combined with others, diluting its problems in the larger pool. At every stage along the long securitization chain, there was a belief that someone—someone else—would catch mistakes and preserve the integrity of the process. The mortgage lender counted on the Wall Street investment banker, who counted on the CDO manager, who counted on the ratings analyst or perhaps the regulator.

In the period leading up to the subprime financial shock, America’s financial ingenuity seemed without parallel. Our best financial minds appeared to have devised a machine to channel the world’s savings into productive uses more efficiently and with less risk than ever before. The machine’s engineers were reaping unimaginable benefits—billions of dollars a year in compensation were going to just a few thousand individuals. There were a few complaints, but they were faint; households with no prospects for homeownership just a few years earlier were now becoming homeowners.

Yet it turned out the machine was running amok, as all along the chain, everybody assumed someone else was in control.