9. As the Regulatory Cycle Turns

No part of the nation’s economic life has more legal and regulatory oversight than housing and mortgages. Federal and state government agencies have a say in nearly every stage of mortgage lending, from determining whether a loan is appropriate to deciding how to foreclose on a defaulting homeowner. Yet regulatory supervision all but disappeared during the housing boom. Where were the regulators?

It wasn’t as if regulators didn’t understand subprime lending’s risks. They had dealt with the issue in the mid- and late 1990s, when home equity lenders—that period’s subprime pioneers—were aggressively making loans. Many of those home equity loans defaulted, and many of those lenders went belly-up by the end of the decade. Regulators responded in 1999 and again in early 2001 by “issuing guidance”—sending an official warning to lenders about the perils of such lending. The regulators told lenders to be sure they set aside adequate reserves to cover the potential losses on risky subprime loans and also warned lenders to avoid predatory lending.

Regulators carefully defined a “predatory” loan as one made without regard to the borrowers’ ability to make timely payments.1 Lenders had to do more than make sure the borrower’s house was worth more than the amount of the mortgage; they also had to determine that borrowers had enough income to stay current on the loan. Loans that appeared designed mainly to generate fees for the lender were also declared predatory. A refinancing deal that did not lower the borrower’s monthly payment or allow the borrower to take cash out of the house fell into the category of predatory practices, as did lying or withholding relevant information to make a loan to unsophisticated borrowers.

Yet as the subprime market heated up not long after the 2001 guidance was issued, predatory lending practices spread. Lenders appeared to be violating the rules’ spirit, if not the letter. The nation’s mortgage regulators largely went silent. They might slap the hand of a small lender for something particularly egregious; a few tweaks were made to the rules regarding property appraisals and mortgage fraud. But regulators had little of consequence to say during the housing bubble of the mid-2000s.

Not until late 2006, well after the bubble had begun to burst, did regulators issue their first formal guidance on what they called “nontraditional mortgage products.”2 Regulators had debated what to say in the guidance for more than a year, and what they finally agreed to still didn’t directly address most subprime lending. Lenders limited their own definition of “nontraditional” mortgages to interest-only and negative-amortization loans, in which borrowers were allowed to pay less each month than the actual interest due, with the difference added to the principal amount of the loan. Most such deals were, in fact, prime—not subprime—loans.

The late 2006 guidance was much needed, but it was clearly too little and too late. It included some instructions that might have been considered common sense: For instance, lenders should not qualify borrowers for a loan based on low introductory “teaser” rates, but rather should ask whether a borrower had enough income to pay the higher rates that would kick in down the road. The guidance warned against making loans with no verification of income and savings, and it demanded that lenders disclose whether a loan included a large prepayment penalty (as most loans did). The guidance was fashioned by federal regulators, but it quickly became national policy as mortgage-industry regulators at all levels of government adopted it. It was a laudable step; unfortunately, the mortgages whose defaults would precipitate the subprime financial shock had already been made.

Federal and state regulators finally addressed subprime lending formally in June 2007, just weeks before the financial shock hit.3 In this guidance, regulators told subprime lenders to qualify borrowers assuming a loan’s full monthly cost, not just at the low initial teaser interest rate. Borrowers hit with large hikes in their mortgage payments would also need to have at least 60 days to refinance into a more favorable loan before they could be charged a prepayment penalty. By the time this guidance went out, however, subprime lending was already evaporating; the new rules applied to a type of lending that was speeding toward extinction.

Too Many Cooks

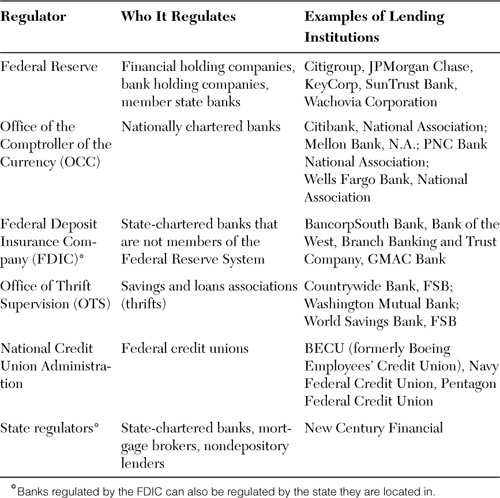

One reason mortgage regulation is not more effective is simply the mishmash of regulators, all overseeing different aspects or regions of the market. Their sheer numbers muddied the response to the frenzy leading up to the subprime financial shock. Some regulators recognized that increasingly easy lending standards would soon be a problem; a few publicly warned of the risks. But with so many diverse groups involved, it was difficult to get a working quorum for decision making.4 At a time when oversight was most desperately needed on mortgages, half the nation’s lenders were regulated at the federal level and half by the states (see Table 9.1).

Table 9.1 Mortgage Lending Regulators

The Federal Reserve Board is by far the nation’s most important banking regulator. It is responsible for keeping an eye on the largest banks and financial holding companies (FHCs), which historically account for about one-fourth of all mortgage lending. Another fourth comes from a hodgepodge of depository institutions, including commercial banks, savings and loans, and credit unions. The federal Office of Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), the Office of Thrift Supervision (OTS), and the National Credit Union Association (NCUA) oversee these lenders.

Federally regulated lenders are not generally subject to state laws, but the states have more than their share of regulatory responsibility.5 States are charged with monitoring the most aggressive mortgage brokers and nonbank lenders, including mortgage finance companies and real estate investment trusts, that accounted for the remaining half of mortgage lending during the boom.6 Most states also require mortgage brokers to be licensed and registered; many, although not all, require the same for individual loan officers. Some loose coordination occurs among the states via umbrella organizations, such as the Conference of State Bank Supervisors and the American Association of Residential Mortgage Regulators.

Other government agencies also have a voice in guiding the mortgage market. The Federal Trade Commission monitors mortgage lenders and brokers’ compliance with antidiscrimination statutes and other federal laws. The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) oversees publicly traded companies, and the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) regulates Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

In some cases, more than one regulator is involved in overseeing a lender’s activities. Wells Fargo & Company, one of the nation’s largest mortgage lenders, is an example. The Federal Reserve watches over the bank’s holding company, whereas the OCC monitors its lending subsidiary. In other cases, lenders receive very little scrutiny. New Century Financial, which made some of the most questionable subprime loans before it went bust, fell under California’s state regulators and the SEC, neither of which had expertise or interest in evaluating the company’s mortgage-lending policies.

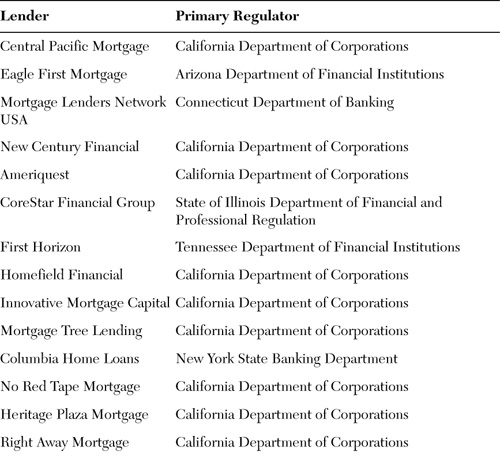

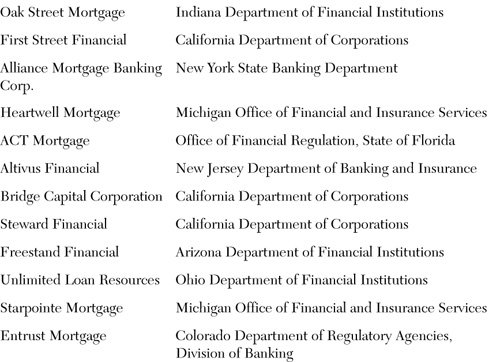

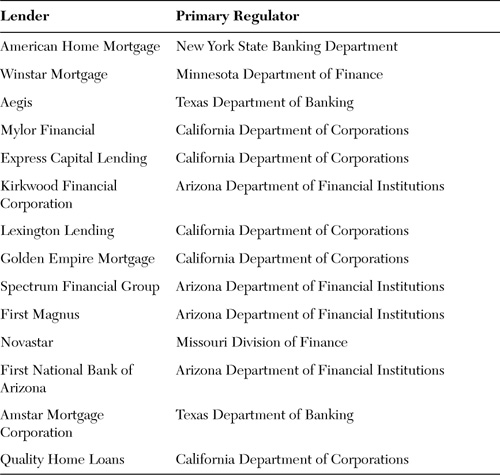

Clear cracks exist in the regulatory patchwork that oversees mortgage lending, and the most aggressive mortgage lenders exploited them during the housing boom. Understaffed state regulators lacked resources to monitor a rapidly growing and increasingly sophisticated mortgage industry; they were the most vulnerable to the most aggressive and least scrupulous lenders, who were also among the biggest casualties when the boom went bust (see Table 9.2).

Table 9.2 Regulators of Bankrupt Mortgage Lenders

Why wasn’t lending better regulated? Beneath the muddle of agencies and authorities was the nation’s long-standing distrust of centralized government authority. The system might have worked well enough in an earlier time, when banking and mortgages were primarily local or at most regional businesses. Regulators knew the lenders in their jurisdiction intimately. As regional barriers to lending came down, the nation’s Byzantine regulatory structure did not change, making its oversight of lenders increasingly unwieldy and ineffective.

Home Ownership Politics

Regulators’ efforts to cool the lending frenzy were also fettered by America’s fierce and long-running devotion to the ideal of home ownership for all. Since the Great Depression, politicians had viewed the percentage of American families who owned their dwellings as a key benchmark of economic success. Regulators were given an open-ended mandate to help drive that number higher. Any agency or administrator who did not actively pursue this vision was roundly criticized.

The pursuit of higher home ownership went into high gear beginning in the 1970s, as it also became a test of the nation’s success in promoting civil rights. The 1977 Community Reinvestment Act had outlawed “redlining,” historically the practice by bankers of defining neighborhoods—literally outlined on maps in red—where they would not make mortgage loans. Such neighborhoods were usually poor and most often home to minorities or out-of-favor ethnic groups. The Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) was meant to actively reverse the effects of such discrimination by offering banks both carrots and sticks to encourage lending in underserved areas. The CRA was given more teeth during the Clinton Administration in the mid-1990s: Regulators could then require banks to explicitly target disadvantaged neighborhoods for both business and home-mortgage lending.

About this time, the Federal Reserve also unveiled new statistical methods for detecting discrimination in mortgage lending.7 Marrying data from mortgage loan applications and approvals (as required under the 1975 Home Mortgage Disclosure Act) with sophisticated econometric techniques, researchers at the Fed felt they could tell whether lenders were racially discriminating.8 A bank tagged by the Fed’s models could be denied permission to acquire or merge with another bank.9 This was a period of active consolidation in the banking industry, and any institution that could not be a shark quickly became a minnow. Only a handful of banks actually failed the Fed’s test, but they were soon acquired, reinforcing the message from regulators to lenders to push home ownership aggressively.10

The Clinton Administration was especially proud of the rise in home ownership during the 1990s, particularly among lower-income and minority groups. While home ownership rose 7% among white households during the decade, it increased 13% among African-American households and 18% among Hispanic households. This could not have happened without the regulators’ blessing and encouragement.

President Bush readily took up the homeownership baton at the start of his administration in 2001. Owning a home became one pillar of his “ownership society,” a vision in which everyone would possess a stake in the American economy. For millions, this meant owning their own home. In summer 2002, Bush challenged lenders to add 5.5 million new minority homeowners by the end of the decade; in 2003, he signed the American Dream Downpayment Act, a program offering money to lower-income households to help with down payments and closing costs on a first home. Lenders gladly accepted Bush’s challenge.

To reinforce this effort, the Bush Administration put substantial pressure on Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to increase their funding of mortgage loans to lower-income groups. Both Fannie and Freddie had been shown to have substantial problems during the corporate accounting scandals in the early 2000s, and both were willing to go along with any request from the administration. OFHEO, their regulator at the time, set aggressive goals for the two giant institutions, which they met in part by purchasing subprime and alt-A mortgage securities. By the time of the subprime financial shock, both had become sizable buyers of the Aaa tranches of these securities.

Democrats in Congress were worried about increasing evidence of predatory lending. Some noted that the 2001 rule prohibiting such lending applied only to federally regulated lenders. North Carolina had passed a law banning predatory practices in 1999, and the Democrats wanted a federal equivalent that would cover all lenders nationwide. The Bush Administration and most Republicans in Congress were opposed, believing legislation would overly restrict lending and thus slow the march of home ownership; moreover, the Republicans argued, existing regulations were adequate to discourage the worst excesses. The last attempt to pass anti–predatory lending legislation occurred in 2005, but it was also stymied. It was thus up to regulators to strike the appropriate balance between promoting home ownership and ensuring prudent lending. All too obviously, they failed to strike that balance.

Greenspan’s Regulatory Failure

The Federal Reserve not only sets monetary policy, but it also plays a central role in guiding the nation’s banking regulatory infrastructure. Without the Fed’s leadership, other regulators could not take an effective stand against the frenzied mortgage lending of the early 2000s. But the Greenspan-led Fed was not eager to use its considerable authority to significantly curtail mortgage lending.

The Fed’s regulatory stature stems from its intimate relationship with the largest financial institutions, established as part of its monetary policy responsibilities. Given the importance of these institutions to the entire financial system, policies set by the Fed quickly radiate throughout the system. The Fed’s leadership also stems from its enormous financial and intellectual resources; more economists work in the Fed system than in any other institution in the world. Most important, the Fed is largely independent: Although it is not completely outside the political process, it is more able than any other regulator to adopt policies and positions without regard to what the president or Congress think.

Chairman Greenspan’s reluctance to flex the Fed’s regulatory muscles stemmed from his own oft-voiced skepticism about regulation. Greenspan believed a well-functioning market with the appropriate incentives could police itself more effectively than could government bureaucrats. Mortgage lending qualifies as such a market, Greenspan thought. Lenders ultimately had to answer to smart and self-interested global investors, who surely saw no lasting profit in making bad mortgage loans.

Greenspan wasn’t the only policymaker who held such views; the 1980s and 1990s had been marked by a steady march toward deregulation. The trend climaxed in 1999 with Congressional passage of the Gramm–Leach–Bliley bill, which overturned Depression-era banking laws barring banks from merging with securities dealers and insurance firms. The resulting financial holding companies were put under the regulatory domain of the Federal Reserve. The Basel II rules on banks’ capital reserve requirements were being fashioned at about the same time. These rules rely heavily on market forces. How much capital banks need, and, therefore, how aggressive they can be in their lending, is determined mainly by the market value of their holdings. The fashion in banking circles was to let the market—not old-fashioned regulators—determine what was appropriate.

Some notable dissent on this came from within the Federal Reserve itself. Fed governor Edward Gramlich, a well-respected former economics professor from the University of Michigan, was notably vocal early in the lending boom. Gramlich, who was responsible for consumer affairs at the Fed, felt that the central bank should take the lead in weeding out predatory lending by examining both the federally regulated banks, which were under the Fed’s auspices, and their mortgage affiliates, which were not.11 These proposals went nowhere. Chairman Greenspan argued that Gramlich’s proposed examinations would not have stopped shady lending and that they might inadvertently bestow on shady lenders the ability to claim the Fed’s seal of approval.12

At various times, Congress also exhorted the Fed to address nagging concerns about excesses in the mortgage market. In 1994, the House and Senate passed the Home Ownership and Equity Protection Act (HOEPA), which authorized the Fed to prohibit unfair or deceptive mortgage lending.13 Under HOEPA, the Fed has the authority to prohibit predatory lending practices by any lender, no matter who regulates it. The Fed used these powers only sparingly, arguing against the need for blanket rules on unfairness or deception. Each case is different, Fed officials claimed.

Almost a decade later, Congressional Democrats pushed the Fed to use its authority under the Federal Trade Act to write rules on unfair and deceptive lending practices. Again, it was to no avail. Greenspan tossed the ball back to Congress, saying the legislature was better suited to define the practices it wanted to bar and make whatever laws were necessary. In other words, if there was improper lending going on, Congress would have to deal with it—not the Fed, and not, by extension, the nation’s bank regulators.

Don’t Worry, Be Happy

Although Greenspan ultimately acknowledged that he had erred in thinking that the market would discipline lenders, his doubts about banking regulation were not without merit. Among other problems, it is hard for regulators to avoid getting caught up in the same euphoria that envelops lenders during good times. Instead of restraining overly aggressive lenders in such periods, regulators may encourage them.

The housing boom period illustrates the point. Mortgage credit conditions couldn’t have seemed better in those years. By 2005, with unemployment declining and house prices surging, delinquencies and defaults had dropped to record lows. Hardly a borrower in San Diego or Miami was even late with a payment. Regulators would have had great difficulty making the case to lenders that their lending standards were out of whack: The regulators had no tangible evidence to point to, even if they had wanted some.

Regulators also could not keep up with the explosion of new and increasingly complex mortgage loans. Although interest-only, negative-amortization, and subprime loans had been around in some form for years, they had never been offered so widely to all kinds of borrowers in parts of the country where they had never before been available. Regulators didn’t have time to evaluate all the new arrangements, let alone determine whether they were appropriate or what to do if they were not.

State regulators were particularly ill equipped to confront lenders, especially in states where housing was at its frothiest. Many state agencies were completely outmanned. At the peak of California’s housing boom, for example, no more than 30 state examiners watched over nearly 5,000 consumer finance companies, including some of the nation’s most aggressive mortgage lenders.14 The massive workload effectively reduced examiners to bookkeepers who could only check to make sure that companies had adequate reserves and were not overcharging borrowers. Mortgage companies could expect an examination from state regulators about once every four years. When the bust came, some of the biggest casualties involved subprime lenders that had been examined just a few months before filing for bankruptcy.

Many state regulators also felt pressure from local politicians to keep mortgage credit flowing freely to their constituents. Examiners were asked to strike a difficult balance between regulating and encouraging home buying and lending. When house prices were high and mortgage delinquencies low, it was difficult enough to warn lenders that they might be overdoing it, let alone force them to rein in their lending.

Searching for a Voice

As mortgage loan quality weakened and foreclosures began to mount in 2006, regulators finally got their bearings. Federal agencies jointly issued the October 2006 guidance cracking down on nontraditional mortgage lending and followed in June 2007 with a statement on subprime loans. The Federal Reserve, now under the leadership of Chairman Ben Bernanke, began a series of hearings about protecting mortgage borrowers. HOEPA had given the Fed the authority for this in the mid-1990s, but not until the housing bust was the central bank willing to take on the job in a comprehensive way.

Finally, in December 2007, the Fed proposed some commonsense lending rules. Firms that made “higher-priced” (mostly subprime) loans would have to consider the borrower’s ability to repay and would have to verify the borrower’s income and assets. Prepayment penalties were barred if a homeowner refinanced within 60 days after an adjustable loan reset, and borrowers would have to establish an escrow account for taxes and insurance.15 Lenders could not compensate mortgage brokers for steering borrowers to higher-rate loans, nor coerce appraisers to overstate home values. Mortgage services would have to credit borrowers as of the date they received payments. None of these rules were radical; indeed, it is hard to imagine that lending standards had eroded so badly that they were even necessary.

The Fed also began working to reestablish its leadership in mortgage and financial regulation. The central bank issued guidance in early 2007 along with other regulators, encouraging lenders to work with borrowers who were struggling to make their payments, particularly those facing steep adjustable-rate interest resets. Later in the same year, Chairman Bernanke threw his support behind expanding Fannie and Freddie’s mortgage-lending authority, then still a politically controversial idea. The Bush Administration and Congress eventually followed.

In early 2008, Bernanke also supported helping homeowners whose homes’ value had fallen below the amount of their mortgages, a situation called “negative equity.” Bernanke argued that such mortgages might have to be written down, reducing the principal until the homeowner no longer owed more than the home was worth. This was a particularly unpopular view in many parts of the mortgage industry and in Washington, DC. Some mortgage holders had agreed to help troubled borrowers by freezing interest rates or extending the term of their loans, but few were willing to shrink the amount of a borrower’s debt. Much of the Bush Administration, and some in Congress, also argued that such write-downs would amount to a bailout of bad borrowers and lenders. Bernanke countered that negative equity makes borrowers much more likely to default and that write-downs might be necessary to keep foreclosures from spreading uncontrollably like dominoes, dragging down housing and the wider economy.

Some regulators were particularly forthright in their responses to the subprime shock. FDIC Chairwoman Sheila Bair was one of the first to advocate freezing interest rates for subprime adjustable-rate mortgage (ARM) borrowers facing payment resets; she also proposed writing down borrowers’ mortgage debts. John Reich, Director of the federal Office of Thrift Supervision, put forward a plan addressing some of the same concerns. Not only did such efforts illustrate the severity of the subprime shock and its implications for the nation’s financial system, but they also testified to the leadership void left over many years by dormant regulators at the Federal Reserve.

Regulators didn’t create the subprime financial shock, but they did nothing to prevent it. This was a result of, first, policymakers’ distrust of regulation in general and their enduring belief that markets and financial institutions could effectively police themselves; and, second, of the nation’s antiquated regulatory framework. The institutions guiding the nation’s financial system were fashioned during the Great Depression, and as finance evolved rapidly, they remained largely unchanged. An overhaul is indisputably overdue.