Chapter 5. From Gold Standard to Oil Standard

“Having behind us the commercial interests and the laboring interests and all the toiling masses, we shall answer their demands for a gold standard by saying to them, you shall not press down upon the brow of labor this crown of thorns. You shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold.”

William Jennings Bryan, July 9, 1896, National Democratic Convention

Leaving the gold standard in 1971 was a necessary condition for the booms and busts that followed. With gold as an anchor, exchange rates barely move. Without the gold standard, currencies depend on the credibility of central banks. And if central banks lose their credibility, the world’s anchor is the price of oil, not gold.

Gold is scarce. If all the gold that has ever been produced and sold were melted down, it would fit into a cube with sides 20 meters long. This valuable object would fit into the hold of a modern tanker. But gold is an unusually dense metal, so the tanker would sink.

This scarcity has for centuries made gold a coveted asset. But it has never been so coveted as it was in 1980, when a frenzy to buy gold coins pushed the price up to $850 per ounce, 24 times higher than the price of $35 per ounce, at which it had been fixed for decades until 1971. This was the world’s first investment bubble of the post-war era, and it was inflated by opportunistic political fixes that fundamentally shifted the world’s financial dynamics. It made it possible for diverse markets to overheat at once, forming a synchronized bubble.

Gold once anchored the world’s financial system. Once unmoored, the capitalist world suffered a decade of “stagflation” (inflation combined with stagnation) before it regained kilter. The key elements of the new system that has evolved are that the value of money rests on the credibility of central banks; that exchange rates, which set the terms of international trade, are set by markets, not governments; and that the price of oil has replaced the price of gold as the system’s anchor.

Until 1971, the capitalist world followed rules set at the summit the victorious allied powers held in the New Hampshire resort of Bretton Woods in 1944. They returned to the system that had been in place for much of history, where paper banknotes in circulation carried the guarantee that they could be exchanged for a certain amount of gold. As gold is scarce, that put strict limits on the amount of money that governments could print. The aftermath of the First World War, when Germany had lapsed into hyperinflation as it printed money to pay its war debts, suggested to the leaders that this was necessary.

Under the Bretton Woods system, the gold price was fixed in dollars at $35 per ounce, and other currencies’ exchange rates were fixed to the dollar. Hence gold anchored all currencies, which remained broadly fixed against each other. The money supply was limited so it was hard for inflation to rise. During the Bretton Woods era, the capitalist world largely avoided banking crises, and investment bubbles. Economic growth was steady, although punctuated by recessions. But the system was a straitjacket for governments with expensive ambitions, and put the onus on the United States to be the banker for the entire capitalist world. This became harder and harder.

By 1971, the gold standard was having much the same effect on the U.S. economy as a cube of gold might have on a supertanker. Foreign governments, ever keener to convert their dollars into gold, had outstanding claims of $36 billion against only $18 billion in gold reserves that the United States had put aside for the purpose.1 Meanwhile, the costs of the Vietnam War and the expansive social programs of the 1960s weighed on the budget. And Richard Nixon, the incumbent president, wanted to be re-elected the following year.

The United States had already resorted to numerous fixes to balance the books, but the numbers did not add up. After a momentous summer weekend at the presidential retreat in Camp David, Nixon announced with little fanfare that foreigners could no longer exchange their paper dollars for gold. Nixon portrayed the move as a “triumph and a fresh start.”2

By doing this, he stood in a populist American tradition of opposition to the gold standard that stretched back at least as far as the presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan, who in 1896 proclaimed that the United States was “crucified on a cross of gold” and demanded to adulterate the currency and boost the money supply by mixing in silver.

In the short-term, Nixon’s closing of the gold window was an economic master-stroke of the kind Bryan probably envisaged, as it allowed for a pump-priming expansion. Nixon imposed price controls so the Federal Reserve did not have to worry about inflation. There was nothing to stop it printing more money. The total money supply rose by about 10 percent in 1971 (the greatest increase on record), the economy grew by an impressive 5 percent the following year, and Nixon won re-election.

This quick fix highlights many of the gold standard’s problems. Demand for gold is itself irrational—its value is almost entirely in the eye of the beholder. Any new discovery can cause a dramatic increase in its supply. And yet under a gold standard, these factors critically affect the supply of money in the economy. As more and more countries came into the capitalist fold in the 1990s, the world could not possibly have remained tied to gold. The concept was hopelessly outdated.

But the gold standard needed a replacement. Without a link to gold, a currency is merely a creation of governmental fiat. Its strength resides in the reputation of its central bankers. It is not obvious that this is much better, and it creates opportunities to bet against central banks that investors have come to exploit ruthlessly. The investment writer James Grant, a well-known supporter of the gold standard, is scathing: “To strike off a half-ton of a new currency on a printing press takes no great skill. The history of inflation attests to it. Digging up gold out of the earth is a much harder proposition, which is exactly what commended the gold standard to our monetary forebears.”3

Far from happening in a vacuum, Nixon’s neat opportunism changed the rules of world trade. The effect on the dollar was instant. Within months the gold price had moved from $35 per ounce to $44 per ounce. Trading partners who had been holding on to piles of dollars found that they bought 25 percent less gold. This ended the Bretton Woods era. Currencies floated, exchange rates diverged, and the world soon experienced the first swing of the balancing system that has remained in place ever since. It is now run by the oil market.

As far as the oil exporters on whom the United States depended were concerned, Nixon had just slashed the amount of gold that they received for their oil. From 1971 to late 1973, the price in gold of a barrel dropped by two-thirds. This in part drove the OPEC cartel of mostly Middle-Eastern oil producers to triple oil prices in October 1973, a move that triggered the great 1970s stagflation. And as U.S. inflation increased, so the value of the dollar weakened, spurring a second OPEC oil price hike at the end of the decade.

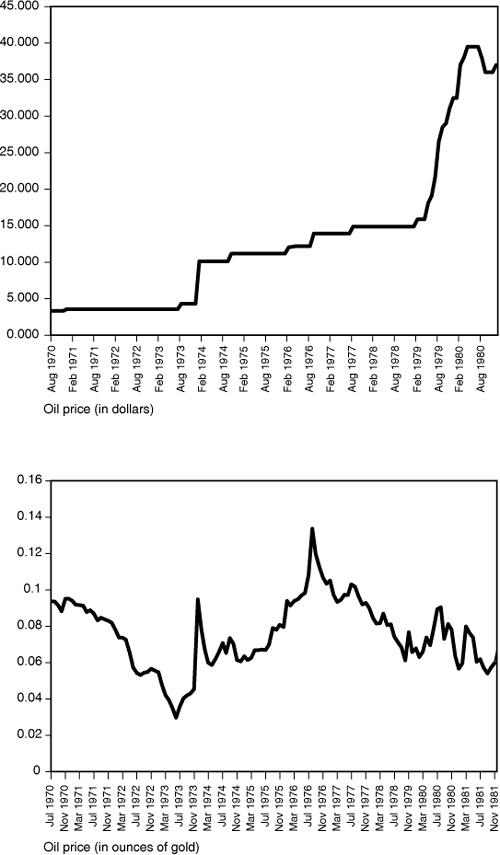

The price of oil in terms of gold suggests that the oil producers had little choice but to raise prices (see Figure 5.1).

Figure 5.1. The 1970s: from the gold standard to the oil standard

As the charts show, the price of oil in dollars may have gone through the roof in the 1970s, but when priced in gold, it was stable—the two great price hikes merely attempted to adjust for the weakened buying power of the dollar. In November 1979, an ounce of gold bought 12 barrels of oil, compared to about 11 barrels in 1971 under the gold standard. Having abandoned the gold standard, the United States found itself instead tied to a new “oil standard.”

OPEC’s actions in turn inflated the bubble in gold. As inflation took hold, investors desperately bought up gold coins, believing this was the only way to hold on to value—perhaps validating the James Grant view that the gold price is “the reciprocal of the world’s faith in the stewards of paper money.” With fear rampant, investors’ loss of confidence in central bankers was extreme. It also gave rise to a wave of speculation, as investors started to pay prices for gold that showed they were betting on the behavior of others, rather than calculating a sensible price for the metal. That is how an ounce of gold went from $35 to $850 in only nine years.

Getting out of the dynamic, like getting into it, rested on a minor act of political expediency. In the summer of 1979, President Jimmy Carter was in trouble, rocked by the deep economic malaise. Reshuffling his cabinet in a bid to revive his fortunes, he had difficulty finding a new treasury secretary, and eventually gave the job to the incumbent head of the Federal Reserve. That left a hole at the Fed, which terrified the markets. Carter’s advisers hurried to find a replacement, and after a weekend of consulting Wall Streeters, decided that Paul Volcker, an economist and lifelong civil servant who then ran the New York Fed, was the best bet to steady the markets. A hasty appointment installed the man who would prove to embody a new gold standard.

Volcker acted drastically to restore confidence in the dollar, raising interest rates repeatedly, squeezing out the credit from the system and forcing the United States into another recession. Markets nosedived. By the summer of 1982, Volcker’s harsh medicine had engineered such a bear market in stocks that they were worth no more, after inflation, than they had been in 1954. Unemployment hit 10.8 percent.4

By going to such extremes, Volcker had earned credibility. His remedy was a blunt instrument, like the gold standard itself, but markets could believe in the value of a paper dollar backed by a Fed that behaved this way. With no fear of inflation, investors did not demand high interest rates on long-term bonds, so rates fell. And so the longest bull market for stocks in history got under way.

The international dynamics that followed Nixon’s devaluation of the dollar with an oil spike and a recession remain in place. Traders now know that a weaker dollar, or higher inflation, will mean higher oil prices. If they fear higher U.S. inflation, therefore, they will buy oil. Unlike gold, oil is plentiful. Tankers full of it ply their trade around the world. But unlike gold, it is central to the workings of an industrial economy, and big swings in its price wreak havoc. The new de facto “oil standard” was destabilizing in the 1970s, and it was again in 2008 and 2009. This relationship led to the synchronized markets of the twenty-first century.

The growing importance of oil also had another consequence: It drove more money toward lesser developed countries that had previously been excluded from the capitalist system. In the 1980s they became ever more tightly linked.

In Summary

• The economically vital markets for oil and foreign exchange are tightly linked. Under the gold standard, they were external to the market, set by governments; now markets determine them.

• A gold standard is probably unworkable in the twenty-first century, but it thwarted excessive devaluations and inflation and would have thwarted the growth of synchronized bubbles.

• Its place has been taken by oil; devaluation and inflation now lead to oil prices so high that they dampen world growth.

• Investors now treat oil as a great hedge against devaluation and inflation.