It is often said that people are the most important resource in any organization. This is certainly true as it applies to systems management. Smooth-running infrastructures are built with robust processes and reliable technologies. But before procedures and products are put in place, first must come the human element. Skilled professionals are needed at the outset to develop plans, design processes, and evaluate technologies; then they are needed to transform these ideas from paper into realities.

This chapter describes various methods you can use to staff an IT infrastructure with appropriately skilled individuals. We start out by looking at how to qualify and quantify the diversity of skill sets required. Next we discuss ways to assess the skill levels of current onboard staff and some not-always-obvious alternative sources for staffing you can use if needed. We then move on to some helpful tips on using recruiters, landing the ideal candidate, and retaining highly sought-after individuals.

Competent IT professionals who are both well-trained and highly experienced in the disciplines of systems management are in short supply and large demand. This chapter offers effective approaches to meet this ever-increasing challenge.

Most newly proposed IT projects begin with a requirements phase. Staffing for systems management also has a requirements phase in the sense that necessary skill sets and skill levels need to be identified and prioritized early on. A skill set is defined as technical familiarity with a particular software product, architecture, or platform. For example, one enterprise may use primarily IBM mainframes with IBM’s information management system (IMS) databases while another may use mostly Sun Solaris platforms with Oracle databases. The skill sets needed to implement systems management functions in these two environments are significantly different.

Within a skill set there is another attribute known as the skill level. The skill level is simply the length of experience and depth of technical expertise an individual has acquired and can apply to a given technology. The process of determining and prioritizing the required skill sets and levels has several benefits:

- Quantifying the skill sets that will be needed to implement selected functions forces you to more accurately reflect the diversity of technical experience your environment will require.

- Estimating necessary skill levels within each required skill set will reflect the amount of technical depth and expertise that will be needed.

- The quantifying and qualifying required skill sets and levels are valuable aids in building the business cases we discussed in the previous chapter.

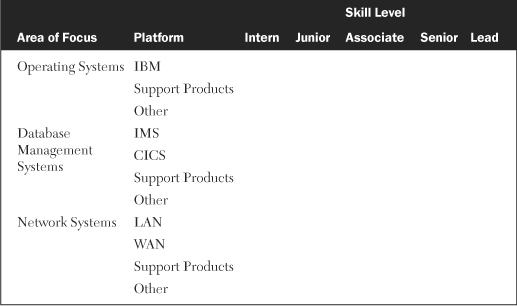

Developing a skill set matrix that is customized for your particular environment can help simplify this process. Table 3-1 shows an example of a skill set matrix for a relatively typical mainframe environment. The first column describes the major areas of focus for which systems management functions would apply and for which staffing would need to be considered. These major groupings would obviously differ from company to company depending on their own particular area of focus. Similarly, the platforms may be different for different enterprises. Next are the five groupings of skill levels, starting with the least experienced intern level and progressing to the senior and lead levels. The value of a table such as this is that it helps to visually qualify the skills that will be needed to implement selected systems management disciplines. The table can also be used to quantify how many individuals will be needed for each skill set and level. Occasionally a skill set and skill level requirement may amount to less than one full-time person. In this case, a decimal portion of a full-time equivalent (FTE) is commonly used to represent the staffing need.

Table 3-2 is similar to Table 3-1 except that it applies to a midrange environment rather than a mainframe one. Several of the platforms have consequently changed, reflecting the difference in environments.

Table 3-3 applies to a client-server environment. The two major platforms are UNIX and Microsoft NT; each platform is delineated by manufacturer. The manufacturer entry for NT is designated as “various” because the skill set for NT tends to be independent of the supplier.

Once we have determined the level and set of skills essential to supporting a particular systems management function, we need to identify potential candidates who have acquired the necessary experience. The first place to look is within your own company. Surprising as it may sound, some firms immediately look outside to fill many IT infrastructure openings rather than pursuing internal staff. Some believe the positions may be too specialized for someone who has not already obtained the skills. Others may feel that the cost and time to retrain is not acceptable.

The fact of the matter is that many companies enjoy unexpected success by redeploying onboard personnel. Potential candidates who are already on board usually are proficient in one or more technologies, but not necessarily in the systems management function being implemented. The more similar the new skill sets are to a person’s existing ones, the more likelihood of success. For instance, the discipline being implemented may involve the performance and tuning of servers running a new flavor of UNIX. Onboard system administrators may be very capable in the performance and tuning of a different, but similar, version of UNIX and thus could easily transition to the new flavor. Redeploying a database administrator into the role of a systems administrator or as a network analyst may be a more challenging.

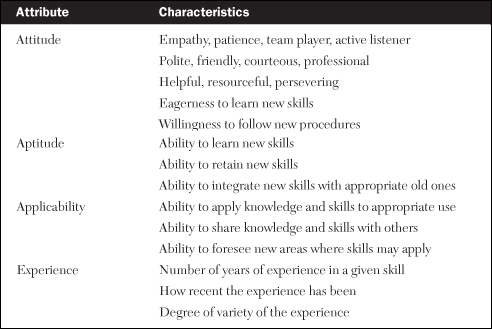

Being able to predict which onboard candidates can successfully transition into a new infrastructure role can be an invaluable skill for IT managers facing staffing needs. I developed a rather simple but effective method to help do this while filling staffing requirements at a major motion picture studio. The method evolved from lengthy analyses that I conducted with the human resources department to identify attributes most desirable in a transitioning employee. After sorting through literally dozens of very specific characteristics, we arrived at four basic but very pertinent qualities: attitude, aptitude, applicability, and experience. While the definition of these traits may seem obvious, it is worth clarifying a few points about each of them.

In my opinion, attitude is the most important feature of all in today’s environment. It implies that the outlook and demeanor of an individual closely matches the desired culture of the enterprise. Some of the most brilliant IT programmers and analysts have become hampered in their careers because they have poor attitudes.

Exactly what constitutes an acceptable or proper attitude may vary slightly from firm to firm, but there generally are a few traits that are common to most organizations. Among these are the following:

• Eagerness to learn new skills

• Willingness to follow new procedures

• Dedication to being a team player

This last trait contrasts with that of aptitude, which emphasizes the ability to learn new skills as opposed to simply the desire to do so.

Applicability refers to an individual’s ability to put his or her skills and experience to effective use. Employees may have years of experience with certain skill sets, but, if lack of motivation or poor communication skills prevent them from effectively applying the knowledge, it is of little value to an organization.

Experience is normally thought of as the total number of years a person has worked with a particular technology. An adage refers to distinguishing between someone who has 10 years of actual experience in an area of expertise versus someone who has one year of experience 10 times over. Depth, variety, and currency are three components of experience that should be factored into any assessment of a person’s skill level.

• Depth refers to the level of technical complexity a person has mastered with a given product or process. An example of this would be the ability to configure operating systems or modify them with software maintenance releases as opposed to simply installing them.

• Variety describes the number of different platforms or environments an individual may have worked in with a certain technology. For example, one person may have familiarity with a multi-platform storage backup system but only in a single version of UNIX environment. Another individual may have a deeper understanding of the product from having used it in several different platform environments.

• Currency refers to how recent the person’s experience is with a given product or technology. IT in general is a rapidly changing industry, and specific technologies within it may become outdated or even obsolete within a few years. A database administrator (DBA), for example, may have extensive familiarity with a particular version of a database management system, but if that experience took place longer than four to five years ago, it may no longer be relevant.

Table 3-4 summarizes the four key characteristics used to assess an individual’s skill potential in transitioning from one infrastructure to another. Additional descriptions are shown for each characteristic to assist in clarifying differences between them.

We can take a more analytical approach to this assessment by applying numerical weights to each of the four key characteristics. These weights may be assigned in terms of their relative importance to the organization in which they are being used. Any magnitude of number can be used, and in general the greater the importance of the attribute the higher the weight. Naturally these weights will vary from company to company. The attribute of an individual is then assessed and given a numerical rating. For example, the rating could be on a 1-to-5 basis with 5 being the best. The weight and rating are then multiplied to compute a score for each attribute. The four computations are then summed for an overall score. This approach is certainly not foolproof. Other factors such as personality, chemistry, and communication skills may override mere numerical scores. But the technique can be useful to narrow down a field of candidates or as additional assessment data. Table 3-5 shows an example of how this method could be used. With a rating range from 1 to 5, the range of overall scores could vary between 10 and 50.

Several alternative sources for infrastructure staffing are available inside most reasonably sized enterprises. One source involves cross-training existing infrastructure personnel in related skill sets. For example, if a company decides to change from one type of UNIX platform to another, a systems administrator who is familiar with only one variation of UNIX may be cross-trained in the alternative version. Similarly, an NT systems administrator may be cross-trained on UNIX.

A more challenging transition, though no less viable, may be between systems administration, database administration, and network administration. In some instances, suitable candidates may be found outside of the infrastructure group. Application departments may be able to supply DBA prospects or performance specialists, and planning groups may offer up metrics analysts. In certain cases, even business units outside of IT may have personnel qualified for selected positions within an IT infrastructure.

Not all infrastructure positions can be filled from inside a company. The introduction of new technologies, company growth, or simple attrition can necessitate the need to go outside a firm to meet staffing requirements.

Larger companies normally have human resources departments to assist in recruiting, scheduling interviews, and clarifying benefits and compensation issues. Smaller firms may need to recruit from the outside directly or use professional recruiters to fill IT infrastructure openings. Recruiting directly saves costs but requires more time and effort on the part of managers; additionally, it may take longer to locate qualified candidates this way.

Several direct recruiting methods exist to aid in this approach. Word-of-mouth recruiting by coworkers and staff can be surprisingly effective. Many companies now offer lucrative incentives for job referrals. Advertising in leading trade publications and local newspapers can also attract qualified talent. Perhaps the quickest and simplest method today is to use the Internet, which businesses of all sizes are now using to post job openings.

The use of outside recruiters is a common practice today, particularly when filling positions requiring critical or advanced technical skills. Recruiters are becoming much more specialized, enabling managers to pick and choose firms that best meet their particular recruiting needs. Care should be taken to ensure that recruiters have a proven track record; references should be requested and checked whenever possible.

Once you have selected your recruiter, you should provide them with very specific information about the type of individual you are seeking. Most reputable recruiting firms have a sizable database of prospective candidates and should be able to match most of your requirements. The more detailed the job description, the more likely they will find a desirable candidate. Do not specify merely the skill set and level of experience required. Describe the specific kind of work you anticipate the new hire to perform, the types and versions of software products and platforms involved, and the amount of recent practical experience you expect. For leads and supervisors, request how many individuals were under their leadership and for how long.

A final suggestion on the use of recruiters: Always clarify with the recruiting firm any questions you might have on specific points of a candidate’s resume prior to calling that candidate for an interview.

Once a perspective candidate has been identified, a relatively formal interview process should follow. Both the employer and the potential employee should ask sufficient questions to make sure a good fit is likely. For key positions it may be appropriate to have several key staff members interview the candidate to ensure that a variety of viewpoints are covered and to arrive at a consensus about the candidate.

Telephone interviews sometimes are necessary to accommodate conflicting schedules, especially if multiple people will be involved in the interview process. Whenever possible, however, face-to-face interviews should be conducted to evaluate personality, body language, and other nonverbal cues not apparent over a telephone. Most companies have unique job benefits as well as drawbacks, and all of these should be discussed thoroughly and openly during the interview process. The fewer surprises in store for both the employer and the new hire once employment begins, the better for everyone involved.

For positions involving leadership and supervisory roles, you should almost always require references. Request a minimum of two and preferably three or four, and then thoroughly follow up on them. When company benefits are explained to prospective candidates, the explanation should be very thorough; it is usually best handled by a person in the company’s human resources department.

Once a candidate has accepted the job offer, the challenge of staffing now shifts to retaining this person (along with all the other highly talented personnel). IT departments and human resources groups have been struggling with this phenomenon for years. As a result, some creative approaches have been used to stem the tide of turnover and attrition.

Some of these new approaches involve creative compensation such as supplying personnel with free cell phone use, remote Internet access from home, laptop computers, or compensating them for business mileage. Recent research suggests that several nonmonetary factors often are just as important as cash salary. These nonmonetary incentives include the amount of on-the-job training to be provided, the currency of technology used, attendance at conferences and seminars, the meaningfulness and significance of the work being performed, promotion opportunities, and the stability of the management staff.

More often than not, skilled technical professionals change jobs because of some key ingredient missing in the relationship they have with an immediate manager. We have all heard about the importance of communication, but it is hard to overstate its significance. Over the years I have come to know several highly skilled IT professionals who left an otherwise excellent job opportunity simply because of poor communication with their managers. Lack of recognition, little career planning, and their managers’ inabilities to convey an organization’s vision, direction, and goals are some other common reasons employees cite when discussing a poor management relationship.

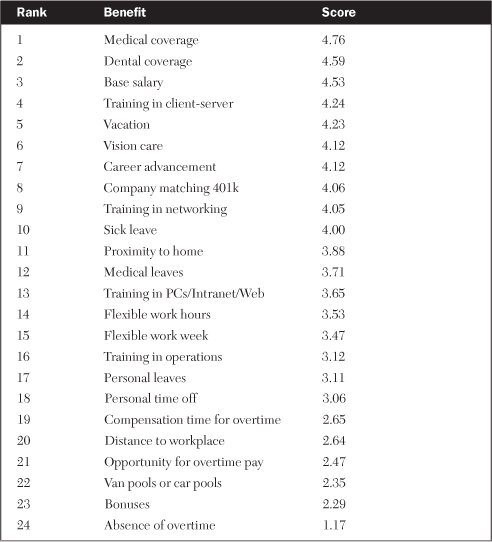

A few years ago I headed up an outsourcing effort at a major film studio. One of the unfortunate circumstances of the project was that a number of good employees would need to be redeployed by the prospective outsourcer. To mitigate the adverse effect of this displacement, we requested that each prospective outsourcing bidder itemize the employee benefits that they would offer to our former employees. The quantity and quality of these benefits would become part of our evaluation criteria in selecting an eventual winner of the contract.

To ensure that we were evaluating the proposed benefits appropriately, I also worked with our human resources department to survey our employees to determine which benefits meant the most to them. We jointly comprised what we all felt was a comprehensive list of typical employee benefits, including those that would likely come into play during a change in companies. We then asked each employee to indicate the level of importance they would give to each benefit. The rating was to be made on a 1 to 5 scale; 1 indicated the least important benefit and 5 indicated the most important benefit

The results of the employee benefit survey were surprising, even to some of the more seasoned human resources representatives. The responses (see Table 3-6) provide some interesting insight into employee priorities. Each benefit is ranked from most important to least important according to its average score. As shown in the table, salary was not the highest priority benefit, although it was close to the top. Medical care was first.

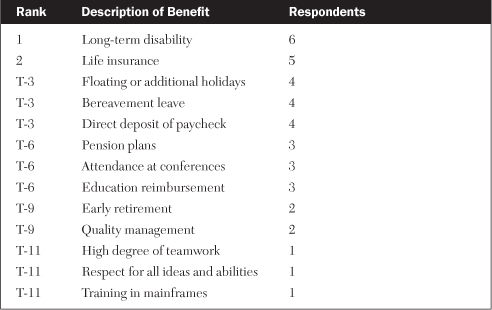

Even more surprising was the list of additional benefits that we asked employees to propose. We felt we had compiled a fairly thorough list of traditional benefits and were not expecting to receive more than two or three newly proposed benefits. As shown in Table 3-7, we underestimated the creative talents of our staff as they proposed an additional 13 benefits. Each benefit is ranked from most important to least important according to the total number of respondents who selected it.

Another alternative available to infrastructure managers needing to fill positions is the use of consultants and contractors. Their use in IT environments in general, and in IT infrastructures in particular, is increasing at a rapid rate for a variety of reasons. Outsourcing, company downsizing, acquisitions and mergers, and global competition are leading to significant reductions in full-time IT staff.

This trend toward reduced IT staffing—especially in larger, more established shops—is also feeding the supply of ready consultants. Many of the previously displaced IT personnel elect to become independent consultants. Frequently many of these former workers enter into service contracts with their previous employers. Others market their skills to companies with IT environments similar to their previous company to ensure a good fit between the skills they can offer and the technical requirements needing to be met.

The explosive growth of the Web and the flood of Internet start-up companies have also contributed to unprecedented demand for IT consulting services. Integrating dissimilar architectures—database software, desktop operating systems, and networking technologies, for example—often requires specialized skills. In many cases managers find it easier to contract with a consultant for these specialized skills than to attempt to grow them from within. A heightened awareness of the benefits of new, replaced, or migrated systems is pushing implementation schedules forward. Accelerated schedules are well suited for the immediate availability and short-term commitments offered by consultants and contractors. The shortened project life cycles of open system applications, the rapid deployment of Web-enabled systems, and the intensifying of global competition are some of the forces at work today that fuel this demand for accelerated implementations.

Consultants come in a variety of types, and they contrast slightly with the notion of a contractor. Understanding the differences between the two can help ensure a better fit between the skills being offered and the business requirements needing to be met. The term consultant normally refers to someone hired to do an analytical task, such as a capacity study, a security audit, or a re-engineering assignment. This contrasts with the term contractor, which generally refers to someone hired to perform a more specific task, such as coding an interface or developing a software enhancement.

Consultants are commonly supplied from one of the major accounting firms or from major computer hardware or software suppliers. Contractors, on the other hand, are more likely to come from software development companies or they are in business for themselves. Consultants tend to be oriented toward issues of strategy, service process, and management. Contractors tend to be oriented towards issues of coding, documentation, technology, and deliverables. These orientations then determine the specific type of consultant or contractor to be hired.

Knowing the specific type of person to be hired helps in one other important area—that of teaming with onboard employees. For example, a consultant hired to develop IT customer service levels needs to show empathy toward the customers that he or she is dealing with. Similarly, a contractor hired to work with an existing team of onboard developers must be able to fit in with the members of the group.

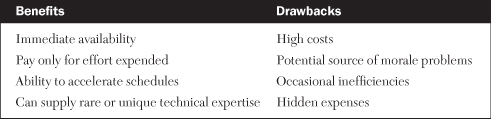

One immediate benefit of using consultants and contractors is that they provide readily available technical expertise. Since they are under contract, you pay only for the time they expend. As the demand for IT services continues to increase, it often becomes difficult—if not impossible—to attract and retain personnel that is skilled, knowledgeable, and highly motivated. This requirement becomes even more challenging as the diversity of IT environments continues to grow. Shops are migrating from one hardware platform to another or from one software architecture to another—be it applications, databases, or operating systems—at ever increasing rates. In the midst of these many transitions, there often may not be the necessary level of technical expertise onboard at the time to perform the migration, support, or maintenance of these systems. Highly specialized consultants can help alleviate this by providing technical expertise needed in these diverse areas.

Another benefit that consultants and especially contractors offer to an enterprise is that they can assist in accelerating critical development schedules. The schedule to implement some major applications is often dictated by specific needs. For example, a critical distribution system for a major toy company may have been cost-justified because it absolutely had to be in place before the Christmas rush. New systems that were designed to correct the Y2K problem obviously had to be in place prior to the start of the new millennium. Organizations may have the necessary quality of skilled employees onboard, but simply not an adequate quantity of them to meet critical schedules. In these instances, consultants and contractors may quickly be brought in to assist in keeping projects on schedule.

Occasionally a highly unique technical requirement may arise. Even a fully staffed and highly diversified IT department may not possess the unique technical expertise required for such a task. Consultants may be a more cost-effective alternative to hiring full-time personnel, particularly if the implementation of the project is relatively short-lived. Interfacing an NT-based application with a UNIX/Oracle database environment may be an example of this.

One of the primary drawbacks of using consultants and contractors is that they are often much more expensive than onboard staff. The rates of critically skilled consultants from key suppliers or major accounting firms can easily exceed multiple thousands of dollars per day per individual. But if the need is of a high enough urgency, expense may not be a prime factor.

Another drawback that occasionally occurs in larger shops is that it has an adverse effect on employee morale. Consultants and contractors who are highly skilled in a critical technical area may dismiss the need to be good team players. Their extremely high rates may justify in their minds the insistence for priority treatment in order to optimize their time on the clock. Thorough interviewing and reference checks can usually mitigate this concern.

Since most consultants and contractors bill on an hourly or daily basis, there is always the concern that some may not work as efficiently as possible. The more time a consultant spends on a project, the more revenue they generate for themselves. Three areas that are prone to inefficiencies are email, voicemail, and meetings. Email is an excellent mechanism for distributing simple, one-way information to many recipients. It typically does not lend itself to activities such as brainstorming, problem-solving, or personnel issues; with email, tone, emotion, and reactions can easily be misinterpreted. When consultants or contractors use emails for these latter activities instead of limiting the use email for simple communication, a task that may have taken only a few hours can often drag on for days or even weeks.

Voicemail is another area where consultants and contractors can be inefficient. They neglect to employ a simple technique of leaving detailed messages on voicemail about the nature of the call when a called party is not available and instead ask only to have the call returned. This usually results in numerous rounds of time-wasting telephone tag. Efficiency-minded consultants and contractors often can actually resolve issues with voicemail by simply providing specific questions, information, or responses.

Meetings can be time-wasters for consultants and contractors from two standpoints. The first is simple mismanagement of meetings. You can significantly improve a meeting’s efficiency and effectiveness by using commonly accepted meeting practices, such as sending advance online invitations; providing agendas, objectives, action items, and minutes; and assigning a scribe, a timekeeper, and a facilitator. Although contractors (and consultants, especially) need to conduct numerous meetings as part of the performance of their duties, few follow many of these common meeting practices. The second way to waste time with meetings is to hold them when they’re not needed. Often a brief face-to-face discussion or even a telephone call may accomplish the same result as a costly and time-consuming meeting.

A final drawback of using consultants and contractors is the issue of hidden costs. The total cost of employing a consultant or contractor is not always apparent when the initial contract is drawn up. Some of these hidden costs include costs for office space, parking, and long-distance telephone calls. Most consultants today have their own laptop computers or access to a desktop. But an independent contractor who is employed primarily to do coding work may require access to a company desktop computer, login authority to the company network, and printing services. All of these activities require setup time, administration work, and other expenses not specifically spelled out in the initial contract.

Table 3-8 summarizes the benefits and drawbacks of using consultants and contractors.

The opportunity for career advancement is one of the most important considerations that perspective candidates factor into their decisions to accept employment offers. Table 3-6 shows a prioritized listing of benefits that candidates prefer the most. The opportunity for advancement and training in current technologies (such as client-servers, networking, PCs, the Internet, and Web design) are among the most desired. Surprising, managers and employees alike often lose sight of this important aspect once the employment contract is signed and work quickly begins. The nature of IT work, particularly within IT infrastructures, is usually so fast-paced that even well-intentioned plans of career-pathing are often relegated to lower priority status. It is the responsibility of both the manager and the employee to ensure this does not happen.

The following three steps can help managers ensure that career-pathing does not become de-emphasized:

- Conduct a skills assessment of each member of your staff. This should determine what technical or managerial skills each member currently has or aspires to obtain.

- Match the future needs of your organization to those individuals who express similar goals.

- Plan out a career program of training, assignments, and mentoring to help the employee and the organization obtain the desired results.

There are also three steps for employees to enable career-pathing to stay on the front burner of priorities:

- Determine your short-term career goals (3 to 5 years) and long-term career goals (10 to 20 years).

If you are fresh out of college or a technical institution, you likely will be pursuing a technical career path. Decide which area of IT appeals to you the most and in which area you feel you have the most aptitude. Some students like programming, some enjoy analysis, some prefer translating business problems into technical solutions, while others lean more toward networking or web design. Taking a variety of IT courses in school can help you set an initial path, but do not be reluctant to change course once you are out working in a business environment. Just as an incoming college freshman may change majors a few times during the course of his college career, an IT professional may change his preferred area of IT expertise.

If you have worked in the industry for some time, but never in IT, your short-term goals may include supervisory or managerial positions. This will depend on the type and amount of experience you have and what policies and available positions an employer may have. In any event, long-term goals should also be decided in terms of a technical career, a managerial career, or something in–between (such as project management). Knowing your current short- and long-term career goals keeps you focused on where you want to be and how to stay on course to get there.

- Discuss your short- and long-term career goals with your manager and request his or her assistance in attaining them.

- This suggestion goes hand-in-hand with the second one. Take the initiative to stay abreast of current developments in your chosen area of preference. Investigate websites, join industry organizations, look into certification programs. For example, there are organizations such as the Help Desk Institute, the Service Management Forum, and the Disaster Recovery Institute that deal with the issues of help desks, service management and disaster recovery, respectively.

These suggestions help managers and employees alike keep career advancement and employment development in the forefront. In the long run, that improves the welfare of employees and managers alike—which means it eventually helps the customers.

This chapter presented effective ways to staff your infrastructure organization, presenting techniques to assess a variety of groups of onboard personnel who may be qualified to work in systems management. For those instances where outside hiring is required, we discussed effective ways to attract candidates from other organizations, including the use of recruiters. We then looked at the selection process itself, along with several suggestions for how to retain key personnel. Finally, the chapter concluded with a treatment of the benefits and drawbacks of using consultants and contractors.

1. A skill set is defined as technical familiarity with a particular software product, architecture, or platform. (True or False)

2. Cross-training is typically ineffective as an alternative source of staffing. (True or False)

3. Which of the following is not a component of experience?

a. depth

b. ability

c. variety

d. currency

4. Most newly proposed IT projects begin with a ___________ phase.

5. Describe several of the benefits of cross-training within an IT organization.

1. House of Lies: How Management Consultants Steal Your Watch and Then Tell You the Time; Business Plus; Kiln, Martin; 2005

2. www.mwoodco.com/value/stratstaff.html; Are You Strategic When It Comes To Staffing?; John Poracky, 2000