Regardless of how well we design and implement systems management processes, they will likely fail without the approval and support of senior management. At some point in time, almost all requests for systems management hardware, software, or staffing need approval by IT executives or their superiors. That, in essence, is where the budget buck usually stops. This chapter discusses ways to acquire executive support and approvals, as well as how to ensure their ongoing endorsement.

Before we attempt to gain executive support for systems management processes, we need to be clear on exactly what the expression means. The words systems management may have different meanings for different people. So we begin with a proposed definition for this term.

Among the other topics covered in this chapter will be techniques to build surefire business cases to demonstrate the true value of systems management. Also included will be methods to educate executives on technical issues without alienating them; in addition, you will learn how to develop and use one of the most powerful weapons available in the ongoing battle for budget dollars.

The term systems management may have different meanings for different people. In order to establish a consistent meaning throughout this book, I propose the following definition.

What does this mean? First, as the name implies, this entity is a management activity. It does not mean we will be creating new hardware and software products in and of themselves. It does not mean we will be separately installing some products or services at the exclusion of others. It does mean we will be looking at a group of products and processes which interact with each other to bring stability and responsiveness to an IT environment.

For example, an enterprise may choose to enact a thorough business resumption plan by contracting with one of the major disaster recovery service providers. For the plan to be executed successfully, however, there must be an extensive and flawless data backup and restore process in place. In other words, the overall goal of business resumption depends on both the disaster recovery component and the backup/restore component.

Each of these components, or disciplines, will be addressed at length in separate chapters. The point here is that no one discipline is as effective individually as it is when integrated with complementary disciplines. This is one of the key cornerstones of effective systems management: the integration of separate but related products and processes.

The overall objective of systems management is to bring stability and responsiveness to an IT infrastructure. Stability means that systems are always up and accessible as scheduled. This can present enormous challenges when systems need to be up 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. These challenges will be discussed in detail in the chapter on availability.

Stability is normally measured as a percentage of available uptime for both online and batch applications. Other related gauges include the amount of actual downtime, measured in minutes per day or hours per month; the elapsed time between outages, commonly referred to as the mean time between failures (MTBF); and the average time spent in recovering from an outage, usually called the mean time to recover (MTTR).

Responsiveness refers to how quickly batch jobs or, more commonly, online transactions can be processed and completed. For the batch environment, throughput is measured as the number of jobs processed per hour; turnaround is the average time required to complete a job. For the online environment, response time is measured as the number of completed transactions per second, or the average time in seconds to complete a single transaction. These concepts are all covered extensively in the chapter on performance and tuning.

There are two reasons why executive support is more important today than it has ever been. The first is that more critical functions of systems management are necessary to run contemporary data centers effectively, requiring more key resources and more management support to acquire them. During the initial growth of the use of computers several decades ago, systems management was not as significant a factor in the success of a data center as it is today. In the early 1970s, availability and online response times were key measures of an effective data center. Functions such as storage management, capacity planning, change management, problem management, and disaster recovery were not major factors in the equation for effective computer centers. Fewer functions meant fewer resources were required and less management support was needed to acquire them.

Second, the infrastructure support groups of computer centers from two or three decades ago focused primarily on technical issues. Internal support groups were relatively isolated from outside influences such as executive management, end-users, and to some extent even application software developers. What little contact many internal support personnel had outside of IT was with hardware service engineers or software marketing representatives. Today these internal support groups are frequently bombarded with requests from a user community that is far more technically educated and computer-literate. This includes executives who are much more likely to be technically astute than their counterparts from several years back.

The modern IT executive’s technical knowledge can be a double-edged sword. Many executives have just enough technical knowledge to be budgetarily dangerous, but not enough technical experience to fully appreciate the requirements and importance of a well-implemented infrastructure. That is why executive support for systems management is so critical today.

By the time most IT supervisors reach senior executive positions, they are more oriented toward the goals of the business than they are toward the intricacies of technology. Their peers are typically chief operating officers (COOs), chief financial officers (CFOs), and the heads of various departments such as engineering, manufacturing, operations, distribution, and marketing. Consequently, the focus of most chief information officers (CIOs) is on the application of cost-effective technology, rather than on the technology itself.

Many CIOs insist that well-developed business cases be presented to ensure the cost-effectiveness of IT systems. In its simplest form, a business case is a clear and succinct cost justification for the funds to be expended for new systems or for upgraded support of existing systems. An effective and thorough business case will itemize all of the associated costs of a new system or process and compare it to the expected benefits. One of the major hurdles with this approach is that it is often very difficult to predict accurately the true benefits of a new system or process. Even when the estimated benefits are reasonably accurate, they are seldom described in terms of cost savings. This is because in many instances the paybacks are more qualitative then quantitative.

Dollar costs and dollar savings are the common denominators used by business professionals in making technology decisions. Yet they are the measures least offered by IT professionals in presenting the benefits of a process improvement. This is especially true when estimating the benefits of a particular systems management function. For example, it may be relatively easy to show how an effective availability process reduces downtime by, say, 10 hours per month, but it is much more difficult to quantify the downtime into actual dollars lost. This difficulty stems from the variety of hidden impacts that an outage may have—lost productivity in terms of labor time; rework due to errors or lack of restarts; time lost due to users not knowing exactly when the system comes back up; and lowered morale due to interrupted services.

One way to be effective with business cases is to develop them for the appropriate systems management function. Understanding which functions are the most beneficial to a company at any point in time is critical to acquiring the necessary management support. One aspect sometimes overlooked is that an organization’s dependency on a specific systems management discipline may change to reflect a company’s changed goals. The maturity cycle of a typical Internet, or dotcom, company will serve to illustrate this point.

During the start-up phase of many dotcom companies, the infrastructure function most frequently emphasized is availability. As the number of visitors to a dotcom’s website increases, performance and tuning gain in importance. When the growth of the website starts to accelerate, capacity planning will likely take precedence. Then the maturing of both the company and its infrastructure usually requires more formalized processes for storage management, security, and disaster recovery.

It pays to know exactly which systems management disciplines are most significant to your company at any particular point in time and to be aware that these functions will likely change over time. It is also important to understand which IT business goals are most critical to meeting the business goals of the company. Then you can determine which infrastructure functions are most critical to meeting those IT business goals.

The next step in building an effective business case for selected disciplines of systems management is to meet and confer with senior IT executives to confirm that the infrastructure functions thought to be critical are in fact the correct ones. This meeting should also include prioritizing these functions in the event that multiple functions end up competing for scarce budget dollars.

The most challenging step comes next, in terms of estimating all associated costs of implementing a particular function and doing so with reasonable accuracy. The obvious costs for items such as software licenses and the labor for implementation and operation are easy to identify and quantify. But some costs are occasionally overlooked when implementing a systems management function, and these expenses are summarized as follows:

- Recruiting

- Training

- Office space

- Software enhancements

- Software maintenance

- Hardware upgrades

- Hardware maintenance

- Scheduled outages

By the same token, all associated benefits need to be thoroughly itemized and converted to dollar savings. Like some of the less obvious costs of a function, there are several benefits of implementing a systems management function that are occasionally overlooked:

- Being able to predict capacity shortages before they occur

- Avoiding lost labor time of users by reducing both the frequency and duration of outages

- Increasing productivity by improving response times

- Ensuring business continuity during disaster recovery

- Avoiding the cost of rebuilding databases and reissuing transactions

A final step—one that is seldom pursued, but is capable of adding invaluable credibility to your business case—is to solicit testimonials from customers in other companies about a particular systems management software product. Customers should be selected who are using the product in an environment as similar as possible to your own. It is surprising that this simple technique is not used more frequently—it usually requires little effort, and yet it can strengthen a justification immensely by demonstrating real-life benefits of a product in an actual business setting.

The following list summarizes the basic steps used to develop an effective business case for any number of systems management functions:

- Understand which IT business goals are most critical to a company’s business goals.

- Determine which systems management functions are most critical to meeting the IT business goals that are aligned to those of the company.

- Meet and confer with IT senior management to confirm and prioritize the systems management functions to be acquired.

- Accurately estimate all costs associated with the implementation and maintenance of a particular function.

- Itemize all benefits associated with the function.

- Convert benefits to dollar savings to the extent possible.

- Solicit customer references for the product being proposed.

The best way to talk to executives is in a language with which they are comfortable and familiar. For most senior managers this means presenting information and proposals in commonly used business terms, not technical jargon. IT personnel in infrastructure organizations sometimes become so enthused about the technical merits of a product that they fail to showcase its business benefits effectively. Yet these business benefits are often the very factors that will decide whether a package is approved. Executives need to be educated about the value of systems management in general and about the benefits of individual functions and products in particular.

No matter how compelling your reasons may be for additional IT expenditures, they may fall short of a convincing argument if not expressed in the language of senior management. Your job is to determine exactly what that language is. Some decision makers may speak purely in bottom-line terms, such as the ultimate total cost of ownership. Others may be more financially oriented and focus on items such as depreciation, tax implications, or lease-versus-buy comparisons. Some may prefer descriptive narratives while others choose graphs, charts, and pictures. Regardless of their preference, the closer you can align your proposal to their comfort zone, the more likely you will be to acquire their approval.

During my many years working among IT executives, I have observed three universal principles involving executive support:

Since one of the primary responsibilities of managers is to make decisions, they appreciate when you simplify the decision-making process for them by presenting viable alternatives. For infrastructure decisions, these could involve choices among products, vendors, platforms, or levels of support.

Most managers do not like to be blindsided by business surprises, such as hidden costs, unpredicted delays, or unscheduled outages. The third principle deals with the use of meaningful business metrics. This topic is of such importance that we’ll take some time to explore it here.

A prudent use of meaningful business metrics is a budgetary weapon that offers powerful persuasive capabilities when proposing systems management implementations. To understand more clearly what this weapon is and how to use it to its optimal benefit, it is first worth looking at how many of today’s IT executives ended up in their current positions.

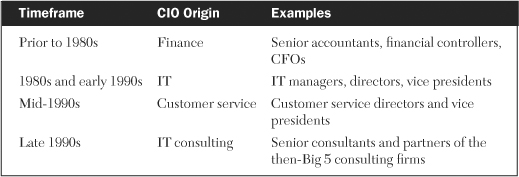

Most of today’s IT executives have risen to positions of senior management from one of four primary career paths (see Table 1-1). The oldest and most traditional path originates from financial departments. In this scenario, senior accountants, controllers, or CFOs ended up running the IT organization of a company since, early on, IT was considered essentially an accounting function of a firm.

A second path became more prevalent in the 1980s and early 1990s, as IT managers became better trained as business leaders to head up IT organizations. In this case, talented IT professionals who had shifted over to a supervisory career path succeeded in transforming their technical expertise into business savvy.

The third alternative started almost as an experiment in the early 1990s. A key external customer with sound business practices and excellent customer service techniques was selected as head of IT despite limited exposure to the technology. This movement was motivated by IT departments finally realizing that they were first and foremost service organizations. Consequently, to survive the growing trends toward outsourcing, downsizing, mergers, and acquisitions, IT organizations needed to make customer service their top priority. What better way to demonstrate this than to assign a qualified customer representative as the head of IT? Some of the risk of this approach was eased by the fact that many user departments had become very computer literate in recent years, particularly as it related to client-server, desktop, and Internet applications.

Toward the end of the 1990s, CIOs also emerged from the IT consulting industry. Though much more limited in numbers than the other types of IT executives, these IT leaders nonetheless made their influence felt, particularly in smaller companies. Three factors contributed to the increased occurrence of consultants becoming CIOs:

• Expanded use of consultants. There was an overall increase of the use of consultants due the expanding growth, complexity, and integration of IT systems worldwide. This gave many senior consultants key access and valuable exposure to IT shops. Thus they could see how the shops should and should not be managed, allowing them to become candidates for the top job.

• The Y2K problem. The unprecedented rush to upgrade or replace Y2K-noncompliant systems gave those consultants who came into companies to do this work access and exposure to most aspects of IT environments, enabling some of them to contend as CIO candidates.

• The rapid rise of dotcom companies. Many of these start-ups hired consultants out of necessity to develop their fledgling IT departments; some stayed on as permanent CIOs.

Regardless of the diversity of their career origins, most CIOs share some important common characteristics in their decision-making process. One of these is to rely on a small number of key ingredients as the basis for critical technical decisions. One of the most common and effective of these ingredients is the use of meaningful business metrics. By this I mean metrics that clearly demonstrate the business value of a decision.

Today’s IT executives work in a fast-paced world of ever-changing technology and ever-increasing demands from customers. They may be faced with dozens of decisions on a daily basis and an even larger number of tasks to juggle and prioritize. Strategies and events that do not require immediate attention are often put on the back burner in favor of those that do. Similarly, executive support for key systems management processes is quickly forgotten and needs to be continually reinforced.

One way to provide this reinforcement is to showcase the successes of your processes. In the case of availability, this could mean showing improvements in system uptime over the course of weeks and months. For tuning processes, it could involve showing increased productivity of users. Remember to speak in the language of your executives and to present information in charts, graphs, or tables. If you are not well versed in exhibiting data in high-level business formats, try scanning business publications such as The Wall Street Journal or USA Today for examples of simple but effective presentation of trends, forecasts, and performance.

Executives tend to be very goal-oriented and results-driven. Their time is valuable and limited. Use it to your best advantage in securing ongoing support for systems management disciplines. Do not assume that because approval was given for previous resources required by an infrastructure process, it will be granted automatically in the future. Just as an IT environment changes rapidly in terms of direction, scope, and focus, so also may the environment of the entire enterprise. The best strategy to ensure ongoing executive support for systems management is to stay informed about the strategies and trends of your enterprise and to keep your senior managers apprised of the synergistic strategies and trends of IT.

This chapter has discussed some techniques to use in capturing and maintaining executive support for the implementation of systems management disciplines. These included building and presenting business cases, educating executives on necessary technical issues without alienating them, and developing and using meaningful, business-oriented metrics—one of the most effective weapons in your arsenal for budget battles.

1. In a business case, all associated costs of a new system are itemized and compared to other expected costs in the organization. (True or False)

2. IT professionals frequently offer dollar costs and dollar savings when presenting the benefits of a process improvement. (True or False)

3. A cost occasionally overlooked when implementing a systems management function is:

a. software development

b. desktop hardware

c. software maintenance

d. network connectivity

4. An important step in building a business case is to solicit testimonials from_________.

5. How can a modern IT executive’s technical knowledge be a double-edged sword?

1. Inside the Minds: Leading Executives on Managing Costs, Negotiating Pricing, and Reducing Overall Technology Spending: Ways to Reduce IT Spending, Aspatore Books, 2004

2. Does IT Matter? Information Technology and the Corrosion of Competitive Advantage, Carr, Nicholas, 2004

3. www.gao.gov/special.pubs/ai94115.pdf (Improving Mission Performance Through Strategic Information Management and Technology, United States General Accounting Office)