24

Work Study

24.1 Introduction

Although modern manufacturing systems are not as labour intensive as they were some years ago, the efficient use of the human resources of energy, skill and intelligence remains very important. This applies not only to manufacturing but to all other industries where labour is employed. The techniques used to ensure efficiency and measure human work are the subject of this chapter. They are generally considered under the term ‘Work Study’; this is a rational discipline in that the techniques ensure a systematic investigation of any situation examined. The two main components of Work Study are Method Study and Work Measurement.

Work Study is generally regarded as the basic tool necessary for increasing human productivity. The concept has probably been around informally since work began, though the scientific methods really saw the greatest period of improvement around the beginning of the twentieth century. These major developments are widely conceded to be mostly attributable to four people, Frederick Winslow Taylor, Frank and Lillian Gilbreth and Charles Bedeaux.

F.W. Taylor was concerned principally with the time factor in work. He realised that the overall times for jobs were of little value as standards of performance and that times for ‘elements’ of jobs were more appropriate if methods were to be examined. Frank and Lillian Gilbreth applied themselves to the methods by which jobs were done. Frank Gilbreth was responsible for defining the 17 fundamental movements by which all manual work could be described. Together, the Gilbreths developed the ‘principles of motion economy’ by which optimum work methods could be developed. Charles Bedeaux was responsible for introducing the concept of rating. This is used to determine how actual observed times differ from the times that should be required. Bedeaux attempted to construct an objective system of Time Study by which work methods could be compared and on which incentive schemes could be based. In Bedeaux's system a common unit was used to describe work on any particular job. This time unit also included rest and relaxation allowances.

Work Study or Motion and Time Study (MTS) remains primarily concerned with discovering the best ways of doing jobs and with establishing standards based upon such methods. It also considers the ‘human element’ and that individuals differ in performance potential. Factors such as sex, age, health, physical size, strength, aptitude, training attitudes, response to motivation and other psychological factors have a direct bearing on output. Workers also dislike being treated as machines, therefore careful consideration must always be given by the Work Study practitioner to worker contact and the interrelationship of both to management.

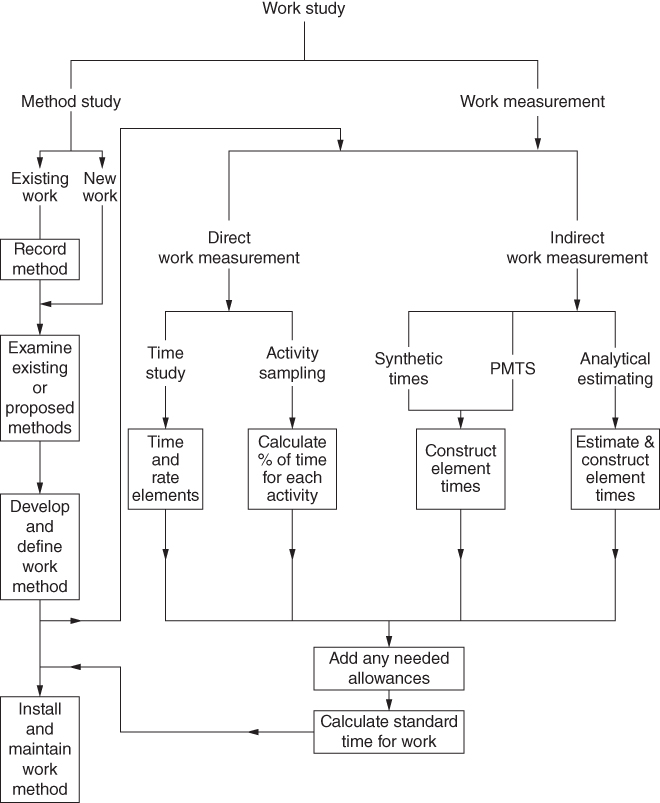

The relationship between Method Study and Work Measurement, and their essential components, is shown in Figure 24.1. Although apparently shown in parallel, it is important to note that Work Measurement should not be carried out unless a proper Method Study has already been undertaken. If this is not the case, then it is quite possible that erroneous times will be applied to jobs, thus making all subsequent costing and estimating exercises worthless.

Figure 24.1 The fabric of Work Study.

24.2 Method Study

Method study involves recording and analysing all factors relating to the manner in which a piece of work is carried out. The work may either be existing or proposed. The aim of the study is to make the job easier, maximise efficiency and minimise costs.

Method Study therefore provides a thorough, step by step approach to achieve the goal of the ‘best’ way of carrying out a work task. The procedure to be followed is widely recognised as that now shown and, although these steps apply to a job already in existence, the general concept also applies when initiating a completely new job.

- Select the work to be studied.

- Record the existing work method and all relevant data.

- Examine the record obtained in the previous step.

- Develop the most efficient or optimum method of work.

- Install this method and adopt as standard practice.

- Maintain this practice.

These six steps are now considered in more detail.

24.2.1 Select

To ensure maximum benefits from the effort put into the Method Study exercise, it is important to select appropriate situations. For example, there would be little benefit in conducting an extensive Work Study investigation in a situation where there was very little manual work and production was dependent mostly on the design of machines. Similarly, if the manual work was temporary or for any reason expected to be short lived, it may be impractical to carry out a full Work Study. However, situations where the duration of the work is short but repetitive, for example, maintenance work, will be suitable for Work Study. The economic results of the study, whether they are increases in output, reductions in scrap, improved safety, reductions in training time or better use of equipment or labour, should always outweigh the cost of the investigation. This maximum cost benefit should not only be sought after by looking at direct costs, but should also be looked for in the indirect cost areas. The human factor should always be considered; thus not only areas where there is apparent wasted time should be studied, but also areas where there is high labour turnover and absenteeism.

24.2.2 Record

There are many recording techniques available for the modern Work Study practitioner. Factors that influence the choice of technique are the rapidity with which the record has to be taken and the amount of detail desired. When first investigating a situation, one of the broad rapid techniques might be used, but as the necessity for examining the detail of the job becomes more important a more time consuming technique may be necessary. Tools such as video cameras are ideal for making permanent records of work for future analysis. Integral digital time displays assist the practitioner to determine durations of work elements. High speed and time lapse photography can also be used. To change the visual record of a job into a form suitable for further analysis, techniques using charts and tables are used. Examples of some industrial problems and their relevant recording techniques are now briefly described.

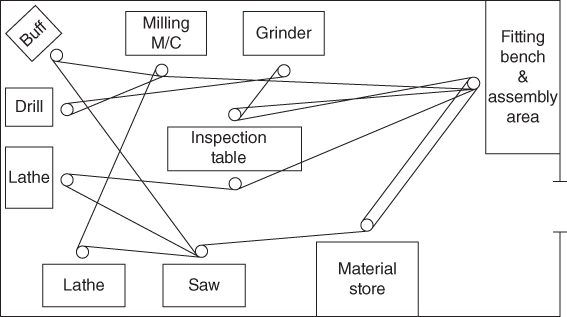

- The techniques associated with plant layout, such as flow and string diagrams, templates, three‐dimensional models and travel charts. Some of these are illustrated in Figure 24.2. They are suitable where large scale movements and areas are being examined without requiring detail to be analysed.

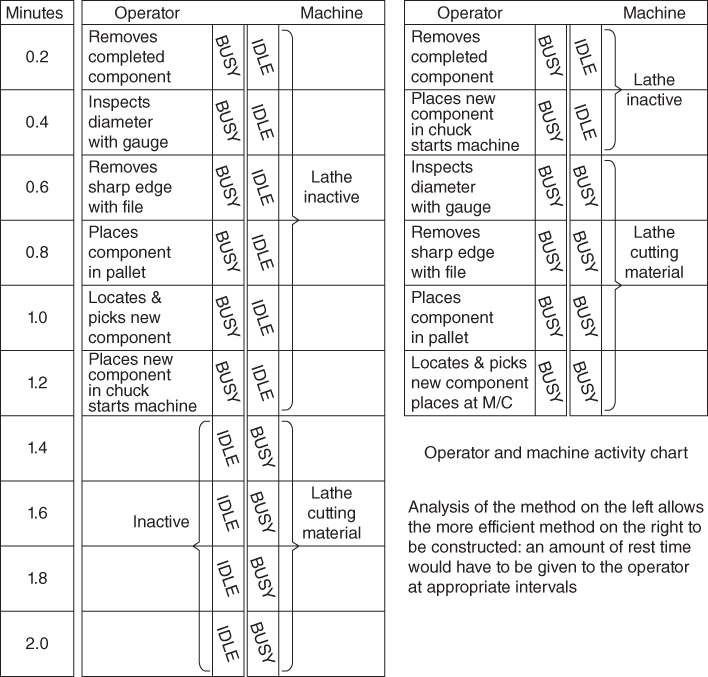

- When the activities of one or more men and/or machines are being examined, then multiple activity charts, activity analysis, or operator and machine charts can be used (see Figure 24.3).

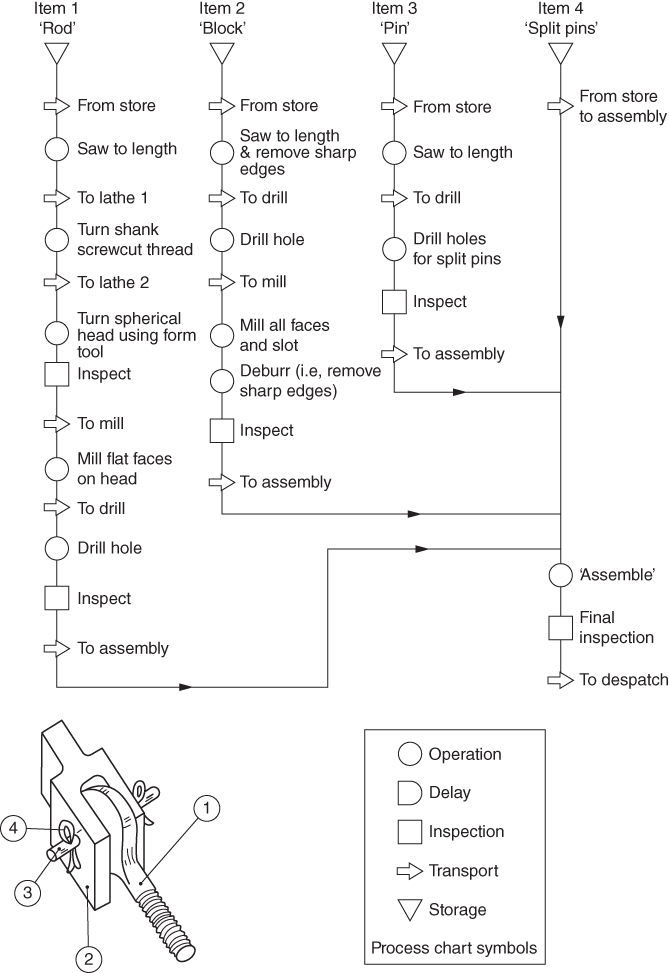

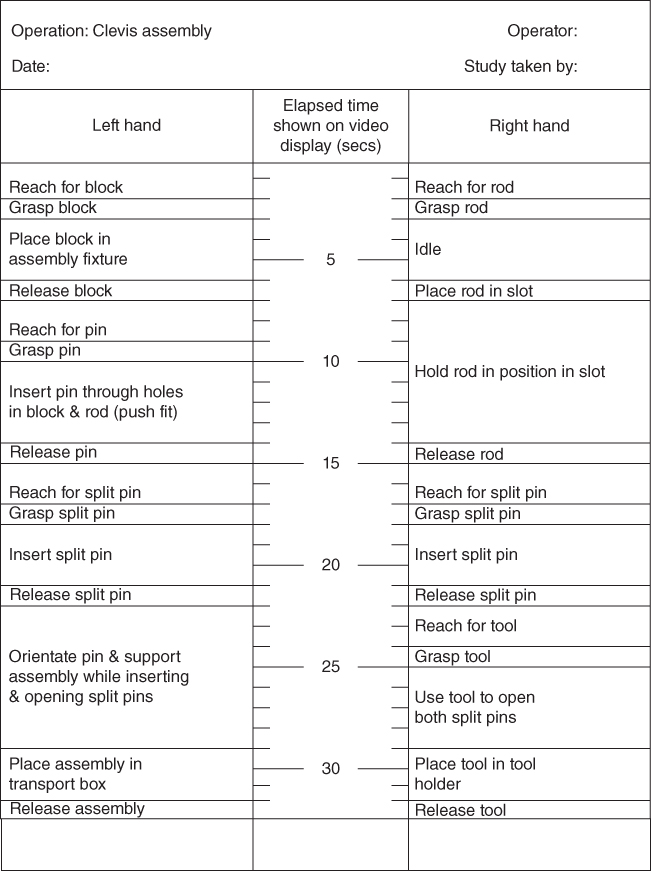

- Process charts. There are many variations of these, for example, the outline process chart, the flow process chart and the two‐handed or operator process chart. These are the most common of the Method Study recording techniques, the sequence of events being represented by a series of symbols that are basically the same for each type of chart. Figure 24.4 shows a clevis assembly chart that uses the clevis rod from Figure 22.7.

- Where long or irregular work cycle times occur, and where studies of groups of workers are required, then memo‐motion photography or work sampling may be employed. In this technique, movements are recorded using a video camera set to take pictures at longer than normal intervals. It is therefore a method of sampling, as activities are observed at regular intervals rather than continuously. When the recording is played back at normal viewing speed, patterns of movement unnoticed in real time often become apparent. Passenger movements in airports and rail stations, the movement of ships in rivers and the flow of customers in large shops or post offices are typical applications of this technique.

- Cyclegraphs are recordings of the paths followed by moving objects obtained by attaching light sources to the objects and photographing the scene using a time exposure camera. The effect is observed by taking a time exposure at night of a city traffic junction. The paths taken by the vehicles using the junction are observed as continuous paths of light on the final print. This effect is utilised by attaching lights to operators' wrists and observing the paths travelled during a particular piece of work, for example, folding a shirt in the garment trade. By rapidly pulsing the lights on and off for specific periods the resulting traces will show up as broken lines. These are known as chronocyclegraphs and by counting the pulses the length of time for each movement can be found.

- When the work movements to be recorded are so complex or fast that the other techniques are inadequate, then SIMO (Simultaneous MOtion cycle) charts are often used (see Figure 24.5). To facilitate the detailed study required, the fundamental movements which together constitute all types of manual work are classified and identified by the use of ‘Therbligs’ (the name ‘Gilbreth’ reversed, see Figure 24.6). The use of these ‘Therbligs’ in conjunction with SIMO Charts is referred to as ‘Micromotion Study’. By using high speed video techniques, complex and intricate finger and hand movements can be filmed and observed in slow motion or frame by frame, and from these observations the SIMO chart can be drawn.

Figure 24.2 Templates, pins and string used to plot the movements of a toolmaker in a small machine shop.

Figure 24.3 Operator and machine activity chart.

Figure 24.4 Clevis assembly process chart.

Figure 24.5 SIMO (simultaneous motion chart) for the assembly operation in Figure 24.4 .

Figure 24.6 Therbligs.

24.2.3 Examine

In this stage, the information recorded is constructively analysed by systematically questioning each activity observed. Assuming that here we are concerned with a manufacturing task, then the recorded activities will fall naturally into two main categories: (i) those in which the material or workpiece is being worked upon, moved or examined and (ii) those in which it is not touched, as it is either in storage or at a standstill owing to a delay. The activities in category (i) may be further subdivided into three groups: (a) ‘Make Ready’ activities, (b) ‘Do’ operations and (c) ‘Put Away’ activities. Thus while ‘Make Ready’ and ‘Put Away’ activities can be represented by ‘transport’ and ‘inspection’ symbols, ‘Do’ operations can be represented only by ‘operation’ symbols. The object of the exercise must be to achieve as high a proportion of ‘Do’ operations as possible, since these are the only ones that carry the product forward in its progress from raw material to completed product. These are ‘productive’ activities and ‘add value’ to the product; all others, however necessary, may be considered as ‘non‐productive’.

There is a well‐established questioning sequence which examines the purpose, place, sequence, person, and means of the activities. This has the aim of eliminating, combining, rearranging or simplifying them. The questioning technique can be set out as follows.

- WHAT is done?

- WHY is it done? What else might be done? What should be done?

- WHERE is it done? Why is it done there? Where else might it be done? Where should it be done?

- WHEN is it done? Why is it done then? When might it be done? When should it be done?

- WHO does it? Why does that person do it? Who else might do it? Who should do it?

- HOW is it done? Why is it done that way? How else might it be done? How should it be done?

These questions are the basis of a successful Method Study and should be asked, in sequence, every time a study is undertaken.

24.2.4 Develop

Just as in the ‘Examine’ stage, there is a methodology for implementing the ‘Develop’ stage. It consists of four steps: eliminate, combine, sequence and simplify. It is applied to each separate activity in the job, that is, each meaningful group of work elements.

The total elimination of unnecessary actions is obviously the first and most important step towards an improved work method. These redundant activities can arise due to changes that have occurred in the product or bad work practices that have gradually been adopted. Once the possibilities of elimination have been exhausted, the combination of actions must be considered, for example, parting off a component in a lathe and facing the following component simultaneously. Next, the opportunities for changing the sequence of actions must be examined, with a view to subsequent further elimination and combination. Finally, if additional improvements are still required then the more costly simplification of the activity may be necessary. This can be done by reducing the number of operations and optimising delays, storage and transportation.

To facilitate simplification, the ‘Principles of Motion Economy’ can be used. These are rules, originally formulated by the Gilbreths, that help ensure that a job will be carried out with the minimum of effort and the maximum achievement. Essentially, they state that work should be designed so that movements are minimised, simultaneous and symmetrical (e.g. two hands working in unison at an assembly task), rhythmical, habitual and continuous.

Once the steps of elimination, combination, sequencing and simplification have been completed, some additional experimental and practical adjustments will probably have to be made. When the practitioner is finally satisfied with the method the last two steps can be implemented.

24.2.5 Install

Due to the human element the steps of installation and maintenance of the method can often be the most difficult. Active support of the practitioner by management and the workers involved is essential. The practitioner should be able to explain clearly and simply what he or she is trying to do, and he or she must have the ability to win the trust of all those affected by the study.

Installation can be divided into five stages:

- Gaining acceptance of the change by the departmental supervision.

- Gaining approval of the change by works and general management.

- Gaining acceptance of the change by the workers and their representatives.

- Retraining the workers to operate the new methods.

- Maintaining close contact with the progress of the job until satisfied that it is running as intended.

24.2.6 Maintain

To ensure the new method is maintained it should be monitored by the Work Study department. This is because human nature is such that a drift away from the method will probably occur if there is no check. Many disputes over time standards arise because the method being followed is not the one for which the time was specified: foreign elements have crept in. If the method is properly maintained, this cannot happen. If it is found that an improvement can be made in the method, then this should be incorporated officially, a new specification drawn up and new time standards set.

Now that the most appropriate method for doing the work has been established, it is necessary to establish the times required to complete the work elements.

24.3 Work Measurement

Work Measurement is the application of one or more of a number of techniques used to determine the time required to carry out a specific piece of work. The principal work measurement techniques are as follows.

First, there are the direct methods of Time Study and Activity Sampling. In these techniques, the Work Study practitioner directly observes the work being measured.

Second, there are the indirect techniques which can be implemented without the physical presence of the work. These are: Synthesis, Predetermined Motion Time Systems (PMTS), Estimating, Analytical Estimating and Comparative Estimating.

The measurement of work is not just desirable but is absolutely essential for both the planning and the control of production. Without work measurement data, it would not be possible to determine what output can be achieved from existing facilities, quote delivery dates and costs, measure the efficiency with which the existing equipment or labour is being used, operate incentive schemes, use standard costs for budget control or determine what extra equipment and labour will be required to achieve a certain output. It may be said that where Method Study is the principal technique for reducing work by eliminating unnecessary movement, work measurement is concerned with investigating, reducing and subsequently eliminating ineffective time. It should be recognised that Method Study and Work Measurement are complementary to each other, one aiding the other to attain the desired organisational goal.

24.3.1 Basic Procedure

As with Method Study so also with Work Measurement a systematic approach is necessary. The steps of this are as follows:

- Select the work to be measured.

- Define the methods to be used. Break the job down into elements. Critically examine the recorded data and the detailed breakdown. This will ensure that the most effective method is being used and that unproductive elements are separated from those that are productive.

- Measure the quantity of work involved in each element, in terms of time, using the appropriate direct or indirect work measurement technique.

- Obtain the total work content plus any allowances.

- Establish the Standard Time for the operation, which will include the time allowances to cover relaxation, personal needs, contingencies and so on. It must be ensured that the series of activities and methods for which the time has been compiled, is defined. Finally, the time will be issued as standard for the activities and methods specified.

24.3.2 The Standard Unit of Work

The concept of using a unit for measuring work is founded on the notion that the human work content of many different types of job can be expressed quantitatively in terms of a common unit. Some terms used by Work Study practitioners in connection with this concept are given next:

- Standard Performance. This is the rate of output at which qualified workers will naturally achieve without overexertion as an average over the working day or shift, provided they adhere to the specified method and provided they are motivated to apply themselves to their work.

- Standard Unit of Work. This is composed of both work and relaxation, the proportion of each varying with the nature of the job. In the British scale, 60 of these units would be created in one hour of unrestricted work at standard performance (standard performance is explained in the Section 2.3.3.1 ‘rating’).

- Work Content. This comprises the basic time and relaxation allowance plus any other allowance for additional work.

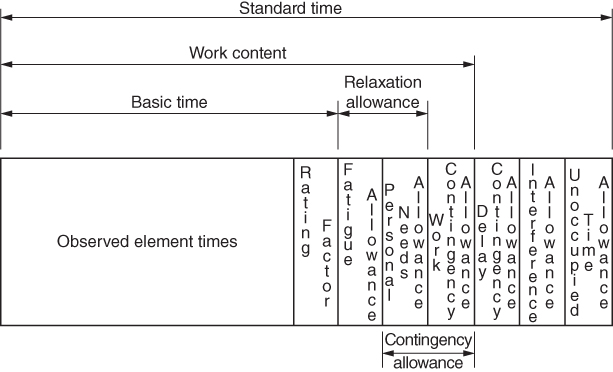

- Standard Time. This is the total time that should be required to complete a job at the Standard Performance. This will be composed of the total Work Content plus allowances, plus any other time that may have to be added for delays and other unoccupied time.

Thus, because the unit of work represents a specific amount of work plus allowances, it has no absolute time value. However, since it must be given some relevant dimension, a figure of 60 units of work per hour at Standard Performance may be adopted. These units are called ‘standard minutes’, so that if one unit of work is carried out at standard performance then it will be completed in one minute of time.

24.3.3 Time Study

Time Study is normally required when there has been a change in the nature of an existing job, or a new job has been started: remember that Time Study should not be attempted until a proper Method Study has been carried out. Time Study is a work measurement technique used for recording the times taken and the rates of working, under specified conditions. It can then be used to establish the Standard Time for the job.

Time scales used when conducting the study may be seconds or decimal fractions of a minute, the latter being the more common and precise. Other time scales, for example, decimal hours, can be used but only in special circumstances.

Traditional Time Study equipment includes a stopwatch, a Time Study board and forms. Video cameras may be used in which the precise timing of the activity is displayed to enable accurate separation of work elements and establishment of their times.

24.3.3.1 Rating

The real object of a work measurement and Time Study is to determine not how long it actually takes to perform a job, but how long it should take. It is therefore necessary to compare the actual rate of working of the operator with a standard rate of working, so that the observed times can be converted into basic times, that is, the time required to carry out an element of work at Standard Performance. This performance rating is the comparison of an actual rate of working against a defined concept of a standard rate of working. This standard rate corresponds to the rate that workers would naturally adopt when working, assuming that they know and follow the specified method, and that they are motivated. On the British Standard performance scale, standard rating is equal to 100. Thus if a worker was rated at 50 he would be working at half the expected standard rate and the time observed would be halved by the practitioner and used as the basis for further calculations. Some practical examples help to create an idea of a standard rate. For example, British Standard 100 is considered to be equivalent to a walking speed of a constant four miles per hour, or to dealing a pack of cards into four hands in 22.5 seconds. We therefore have a scale with the standard rate at 100 and complete inactivity at 0. The practitioner is trained to be able to recognise the conditions of the standard rate of working and to assess to the nearest five points the degree to which a worker's observed speed and effectiveness varies from the 100 standard. The procedure in which the practitioner carries out this assessment, while recording the observed time, is known as rating. The rating is used to find the basic time for a job or an element as shown next:

Basic Time = (Observed Time) × (Rating/Standard Rating), for example, if an operator is rated as being very fast and is allocated a rate of 125, and the observed time was 0.2 minutes, then the Basic Time = 0.2 × (125/100) = 0.25 minutes.

24.3.3.2 Procedure

The procedure for implementing a Time Study is shown in the following.

- First everyone that will be involved in the study should be notified; they should be told the reasons for the study and how it will be conducted.

- Collect and record all relevant information. The conditions under which the work being studied is being done must be recorded; this will provide useful information for the future when estimating times for similar jobs. The record will also be useful if disputes arise at a future date concerning the time established for the job; for example, the method of the tooling may have changed from that in the initial study.

- The work being studied is divided by the practitioner into elements. This facilitates the analysis of the work.

- The elements are timed using a stopwatch or from the digital clock on a video recording. This will be done for a number of work cycles.

- The Basic Time for the work is now calculated, using the gathered data and with consideration given to the rate of working of the operator.

24.3.3.3 Allowances

After the Basic Time has been calculated there is one further step required before a fair Standard Time can be allocated to the job. This involves the allocation of allowances to compensate for the operator fatigue, delays and interruptions that are unavoidable in every work situation. These allowances are composed of the following elements: (i) A Relaxation Allowance to allow the operator to attend to personal needs and to recover physically and mentally from exertion; this may add 10–30% onto the Basic Time, depending on the nature of the work. (ii) Unoccupied Time, which occurs when the worker is unavoidably prevented from doing productive work; this should obviously be minimised if it cannot be eliminated. (iii) A Contingency Allowance to cater for occasional interruptions, adjustments to equipment and so on.

It is now possible to devise the Standard Time for the work that, as mentioned previously, is the total time in which a job should be completed at standard performance; it is shown schematically in Figure 24.7.

Figure 24.7 The build‐up of the ‘Standard Time’ for a work activity.

The foregoing sections have shown how it is possible to use Method Study to determine the most efficient way of carrying out a job, and then to use the Work Measurement technique of Time Study to establish the Work Content and Standard Time.

There are other techniques used in Work Measurement. Another direct measurement technique is Activity Sampling. Here the work is not measured using a timepiece; it is sampled. Activity Sampling is used in situations where it is desired to measure the work of large amounts of people, say in an office. Over a period of time a large number of individual observations are made. At each observation a record is made of what is happening at that moment and the percentage of the observations recorded for a particular activity is taken as representing the actual time during which that activity occurs.

Indirect Work Study techniques include Estimating and PMTS. Estimating is a technique used for determining the time required to carry out a job by using knowledge and experience of similar work done previously. PMTS is a technique that uses times previously established for basic human motions. This synthetic method allows times for jobs to be built up even before the work has started. There are many varieties, but one of the most popular is Methods Time Measurement, which has been developed at three levels. MTM 1 is the most accurate and detailed; it will also take the longest time to implement. MTM 2 is used where the detail of MTM 1 would economically prevent its use. MTM 3 is intended to be used in work situations where at the expense of some accuracy times are required as soon as possible.

24.4 Work Study As a Service to Management

To keep any system in control, for example, an aircraft in flight, an industrial robot or a factory, feedback on the state of that system is required to the system controller. In an industrial organisation the controller is management. Feedback from the shop floor is therefore necessary in the form of quantitative and objective information that can be used to monitor the effectiveness of the labour force. Work Study is the means whereby this information can be produced. The information can also be used by the management for forward planning, for example, to estimate how many man hours will be required to satisfy future customer orders and to estimate future costs.

24.4.1 Labour Control and Reporting

The information coming from the shop floor to the management must be sufficiently detailed to identify specific areas of poor performance, unproductive work or excessive cost. How this is done is best understood by following the process through progressively.

Throughout the day the shop floor workers will spend their time either directly on work for which there is a Standard Time, on diverted work such as repairs or on waiting for material or equipment. Only the direct work is productive and adds value to the product. The operators will record, by writing on report sheets or keying into a computer, how they have spent their time each day. This record will show what products and operations were worked on, how many were produced and how much time was spent on direct and diverted work. It should be noted at this stage that although terminology varies between countries and even factories, the concepts remain the same. Indirect workers such as labourers will also submit reports detailing how they have occupied their time during the day.

From these reports the data processing department will be able to compare the times the operator spent on specific operations against their previously devised standard times. It will then be possible to provide management with information on the performance of the direct operators, the performance of a department excluding the indirect workers and the overall performance that will include all the workers on the shop floor. A breakdown of how the unproductive time was spent will also be supplied; this will enable problem areas to be pinpointed.

The performance figures will probably be supplied in a similar manner to the following:

A short example illustrates the use of these indices.

During a five‐day week a department reports the following information.

| Total Standard Time produced | 450 h |

| Time spent on direct work | 500 h |

| Time spent on indirect work | 80 h |

| Number of operators | 20 h |

| Number of hours available per day | 7.5 |

Calculate the overall performance, the departmental performance, and the operator performance.

Total Attendance Time = 7.5 × 5 × 20 = 750 hours.

| Overall Performance | (450/750) × 100 | 60% |

| Departmental Performance | (450/(750–80)) × 100 | 67% |

| Operator Performance | (450/500) × 100 | 90% |

A detailed report on performance is therefore provided to the management and supervisors. This would normally be supplied to shop floor supervision, for example, foremen, on a daily basis on the day following that on which the work took place; this will enable prompt corrective action to be taken. The supervisor will receive a full report on each individual operator and a composite report for the performance and time utilisation for his department as a whole. Reports will probably be summarised on a weekly basis for line management and factory management will probably receive weekly or monthly reports as appropriate. Action should be taken immediately on the reports, for example, low operator performance needs prompt investigation, as also do instances of high rework or other diverted time. Communicating productivity data to the shop floor is also important. Charts showing various performances for each department can be erected in prominent locations. Charts of quality, for example, reject rates and costs of scrap, are also useful.

24.4.2 Payment by Results (PBR)

In this type of payment system the workforce is usually paid a basic rate plus an amount proportional to performance. This may be on an individual or a group basis. It is apparent that the type of performance indices shown in Section 24.4.1 provide useful data on which to base such systems.

24.4.3 Planning

Since Work study provides a data base of information on how long specific operations should take, the total time required to build products and the methods and equipment required to produce specific quantities of a product, it can be used to predict future manpower and capacity requirements based on anticipated product sales volumes. The total standard times involved in a product can simply be multiplied by the anticipated weekly production target to find the total standard times required per week. This can then be related to the overall performance the factory or departments are achieving to arrive at a total time required for the anticipated production volumes. Knowing the total man hours available per week, this total time can then be used to determine the required manpower.

Review Questions

- 1 What is ‘Work Study’ and what is its purpose?

- 2 What is the principal aim of Method Study?

- 3 Explain the six basic steps that must be taken to complete a successful Method Study.

- 4 What types of work are particularly suitable for Method Study?

- 5 Describe three techniques used in Method Study for recording how work is done.

- 6 What type of questions should be asked when examining the record of how work is done?

- 7 Discuss the four steps necessary for developing a new work method.

- 8 What personal characteristics should the person responsible for implementing a new work method possess?

- 9 What is the principal aim of work measurement?

- 10 Work measurement can be carried out directly or indirectly. Discuss the important differences between these two methods and name two techniques associated with each.

- 11 Discuss the important uses of the information obtained from work measurement.

- 12 Describe the basic procedure for carrying out a work measurement exercise.

- 13 Explain the concept of the ‘standard unit of work’.

- 14 What is the purpose of ‘rating’ in a Time Study exercise?

- 15 List the steps to be followed in conducting a Time Study exercise.

- 16 What is meant by the ‘Standard Time’ for a job? State what elements contribute to its value.

- 17 What is PMTS and under what conditions might it be used in preference to Time Study?

- 18 Discuss how the information obtained from Work Study can be used to analyse the performance of workers on the factory floor.

- 19 Discuss how Work Study can provide information useful for planning future operations.