MODULE 41

Business Continuity

Business continuity consists of all of the planning and processes that an organization undertakes to ensure that it survives and can function after a disaster or incident. This includes identifying critical processes, prioritizing systems and equipment, and determining the business impact if any of these processes or systems are unavailable to the organization for extended periods of time. Since this impact is closely related to risk analysis, this type of planning should be done as part of, and in conjunction with, the organization’s risk management processes.

Additionally, planning involves determining strategies to bring critical services, systems, and data back online after recovery so the business can assume some level of operations. All of the preparation and logistics support must be in place to bring these critical pieces back on line. In this module, the concepts of risk management will be revisited as well as business continuity planning (BCP) concepts. The module will conclude with a discussion of the importance of exercising and testing the business continuity and disaster recovery plans.

Risk Management Best Practices

Business continuity planning activities support the overall risk management program for the organization, simply because parts of these activities seek to identify possible threats to the business and mitigate those threats. Granted, BCP doesn’t cover the full gamut of possible threats and mitigations; it focuses primarily on those associated with incidents and disasters, and the response to those events. It can support the risk management program in a business by helping to identify critical processes, systems, equipment, personnel, and facilities (the assets of the business); the threats to those assets (hack attacks, hurricanes, fires, floods, and so on); and how to mitigate those threats by preserving the ability of the business to operate under detrimental circumstances, and with a possible loss of some of these assets. That’s very much what risk management is about as well, although on a larger and more defined scale. Business continuity and disaster recovery planning go hand-in-hand with risk management, feeding and supporting those processes.

Risk Assessment

As you know, a risk assessment is the activities that focus on the collection of information (threats, assets, vulnerabilities, and impacts) and analysis of that information to determine the degree of damage and impact to a system or business from threats. Risk management also seeks to quantify items such as cost, downtime, and so on, and to determine how those items can be mitigated or reduced. A risk assessment is also performed in the business continuity planning process, albeit a bit more focused on what relevant threats are to business operations and how they impact the business’s ability to function after a negative event. In the BCP context, risk assessments are partially fed by a business impact analysis (BIA), discussed in the upcoming section.

Business Continuity Concepts

Business continuity planning exists to ensure the continued function and operation of the organization in the event of a disaster or serious incident. Not surprisingly, this business continuity doesn’t suddenly plan itself when a disaster has occurred; it requires careful and deliberate planning on the part of organizational members, from executives all the way down to technicians. There is a defined process to business continuity planning, and it essentially starts by identifying the business assets (including equipment, people, systems, data, and processes) and determining how critical they are to the function of the business. These assets are also examined for degree of impact to the business in the event they are lost or nonfunctional during a disaster, and then prioritized for order of recovery. The impact on the business if critical assets and processes are lost could be financial or operational, or it could have other negative effects. In any case, BCP is designed to ensure that these assets are successfully and effectively recovered after a disaster so the business can continue operating. The next few sections outline some of the key processes and activities involved with BCP. You can find a more detailed discussion on business continuity and disaster recovery planning (DRP) in the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Special Publication 800-34, “Contingency Planning Guide for Federal Information Systems,” which was written with government systems in mind but can be used by any business to aid in BCP efforts.

Business Impact Analysis

One of the first steps an organization must take in BCP is to conduct a business impact analysis, or BIA. The BIA is essentially a part of risk management, in that the organization is identifying assets, determining their criticality to the organization, determining the impact if those assets are lost, and prioritizing them for restoration in the event of a disaster. If any of these steps sound familiar, it’s because the BIA process closely mirrors parts of risk management.

The BIA is performed before other BCP and DRP steps, because the business must know what it is protecting and how important those assets are to the business before the organization can plan on how to protect them. Once critical assets and their impacts are determined, the organization can determine how best to protect them and how much resources it can afford to use to protect those assets, based upon differing threats and their likelihood of occurrence.

Identification of Critical Systems and Components

As part of the BIA process, the organization must identify critical systems and their components. Some of this depends upon the different points of view of the users and functional areas within the business, so most functional areas in the organization should be represented when the BIA is performed. For example, both the human resources and accounting functions in the business may each insist that their systems are more critical to the survival of the business than anyone else’s. Likewise, the same might apply for engineering and production functions. This is one reason why top management should be involved in the BIA process, to provide objective decision-making capabilities as to which systems and components are critical, and in what priority they must be restored. Which systems and components are designated as critical may depend upon several factors, including the criticality of the processes they support. For example, if the business’s primary mission is online order fulfillment for different products, then the systems and components directly involved in that process (such as web servers, database servers, financial transaction systems, and so on) will likely be deemed more critical than other support systems, such as human resources and accounting systems. Not to say that those other support systems are not important, but the business may not necessarily depend upon them for survival, at least in the short term, and to get back up and running again.

The organization should define exactly what constitutes a critical system or component. The business may develop different categorizations of criticality, based upon the business process supported. For example, a priority one asset may be deemed as the most critical type, directly supporting the primary business mission. A priority two asset may support secondary business functions or even a support system. The organization could also define criticality in terms of system function. For example, all primary systems supporting the business mission may be designated as a priority one, and any backup or redundant systems may be designated as a priority two. Another such categorization may classify all web servers as priority one, for instance. In any event, the importance of this part of the BIA process can’t be overstated.

Removing Single Points of Failure

If a single point of failure breaks down or fails, there is no other replacement or alternative method to perform the necessary functions it performed. Single points of failure include technologies and equipment such as a single server that processes a critical business function or a system that houses the only copy of a database. A single point of failure doesn’t have to be technological, however. People can also be a single point of failure. For example, suppose only one administrator has access to a particular piece of critical data or an encrypted file. If something happens to that administrator—she leaves the organization or becomes ill or dies—the organization will have lost access to that data or file. Processes can also be single points of failure. Without an alternative way of processing a financial transaction, for example, failure of the particular process involved means that the organization no longer has that capability.

During both the risk assessment and business impact analysis processes, single points of failure can be identified and should be eliminated as efficiently as possible. This can be accomplished by purchasing more equipment (such as a backup server), appointing and training an alternate administrator to perform certain duties or have certain access in the event the primary administrator isn’t available, and looking at processes critically for redundant capabilities. In eliminating single point of failures, redundancy is a key concept. Organization management may be reluctant to include redundant equipment, personnel, or processes, as there is no immediate return-on-investment (ROI) and this can be costly, but they will usually be glad they made the investment the first time a single point of failure actually fails. Redundancy is discussed a bit later in the module.

Business Continuity Planning

The purpose of business continuity planning is to produce a document, the business continuity and disaster recovery plan, which details disaster- and incident-related risks to critical systems, the impact if those systems are lost, and how best to preserve them. This document also specifies how to recover the organization after a disaster and continue business operations. The planning process that goes into producing the BCP and DRP involves personnel from the entire organization, at all management and technical levels. It involves technical personnel, human resources personnel, facilities and security personnel, and representatives from almost every part of the organization. A formal BCP and/or DRP team should be established and mandated with certain goals and tasks. Producing comprehensive BCP and DRP documentation should be one of those tasks, as well as establishing the concrete policies, procedures, and processes necessary to react to an incident, recover from it, and re-establish business operations.

Continuity of Operations

Although they are parts of the same process as a whole, continuity of operations (COO) and disaster recovery are actually two separate activities with distinct goals. Continuity of operations ensures that the business is functioning and operating again in its primary business mission, while disaster recovery is more of an intermediate step between the actual disaster event and bringing the business back to an operational state. Disaster recovery planning is concerned with the reaction and response to a disaster and is focused on saving lives, preventing injury, and preserving equipment, data, and facilities. DRP will be discussed a bit later in the module as well as in Module 42. COO ensures that the business has the appropriate systems, equipment, data, infrastructure, and, of course, people, to resume and maintain operations. This means that considerations such as backups, spare equipment, alternate processing sites, spare supplies, and so on, are equally important in keeping the business up and running. Figure 41-1 illustrates the relationship of business COO and disaster recovery processes and activities.

Figure 41-1 The relationship between continuity of operations and disaster recovery

One fallacy in BCP is the assumption that COO means that the business will be back in a fully operational state equal to what it was before the disaster, but this usually isn’t the case. In a serious disaster, most businesses will likely recover to an operational state that is somewhat diminished from normal function and operations. This is something that should be considered and prepared for during the planning process. The organization should determine the acceptable level for COO and how to achieve that particular target level. The business may need to understand that assuming operations may be on a scaled or incremental basis, particularly in the event of a widespread disaster that affects other organizations, public infrastructures, and so on. Even a 50 percent resumption of operations may be considerably better than none at all and may be even more than other businesses may be able to achieve in a widespread disaster. The organization should set a target COO level and plan on how to achieve that level.

Disaster Recovery

An entire module in this book is devoted to disaster recovery planning, processes, and activities; suffice it to say at this point that DRP is really a subset of BCP. The major difference is that BCP is concerned with planning and getting everything in place such that the business functions can resume after a disaster, while DRP is mostly concerned with the practical and immediate activities following an event that include saving lives, preventing injury, salvaging equipment, relocating the physical business infrastructure to an alternate site, and so on. So, BCP is concerned with business-specific functions and operations, and DRP is more about the recovery operations. Both are important, but each focuses on different parts of the same overall process.

IT Contingency Planning

IT contingency planning involves the planning, processes, and activities focused on maintaining a resilient, available infrastructure. This means ensuring that the organization has all the right IT equipment and systems that are performing their functions and contributing to the business processes of the organization. Contingency planning at first may sound like a short-term process, especially in the context of disaster recovery or business continuity, but it is actually an entire process that covers the life cycle of the entire IT infrastructure in the organization. Equipment and systems become outdated, operating systems require upgrading, software requires patches, and new systems must be installed to handle increased use and provide increased capacity. Planning is required to manage all of these things, over both long and short terms. Contingency planning also means that the appropriate equipment and systems be available in the event of an incident or disaster, and they will be able to process and transfer data even after the loss of infrastructure. This is possible only through the long-term planning process, by purchasing and installing redundant systems, planning on data backups, and using multiple redundant network paths. Not only does this type of planning lend resiliency to normal operations, but it also supports contingencies when there may be a loss of infrastructure.

Succession Planning

We mentioned that redundancy not only applies to equipment and systems, but also to people. In a disaster or incident, there are worst cases that can affect people, such as injury or death, but even in the best cases, critical personnel may not be able to get to the business location due to practical issues such as destroyed roads, massive power outages, weather, and other events that can occur in a disaster. Succession planning ensures that there are available personnel who can step up and lead or perform urgent activities necessary to help the organization recover from a disaster and continue its business operations. Succession planning applies not only to leadership positions, which are of course vital to business recovery and continuity operations, but also to positions that must perform the hands-on work of disaster recovery and business continuity. For example, it’s generally not a wise idea to have only one person who knows how to restore data backups to critical services. In the event of a disaster, that person is a single point of failure and would impede the organization’s ability to restore operations if she can’t make it to the business location to help restore those services. For that reason, every critical position identified during the planning process should also include alternate team members who can fill those roles in the event the primary responsible person is not available.

Likewise, there should also be plans for a leadership chain-of-command and succession in the event key leaders are not available during a disaster. The organization should designate critical leadership positions with both primary personnel and alternates, in a line of succession, so that any leader who cannot respond to the incident has a backup person next in line able to take charge and lead the recovery efforts. These plans should be documented, and all team members should know and understand the leadership succession plan, as well as how other critical positions will be filled by alternates in the event key personnel cannot be present. Training on the duties required by these critical positions must be considered as well. All personnel identified for critical leadership and team member positions must be trained on the duties and responsibilities they will be expected to perform and fulfill in the event of a disaster.

High Availability

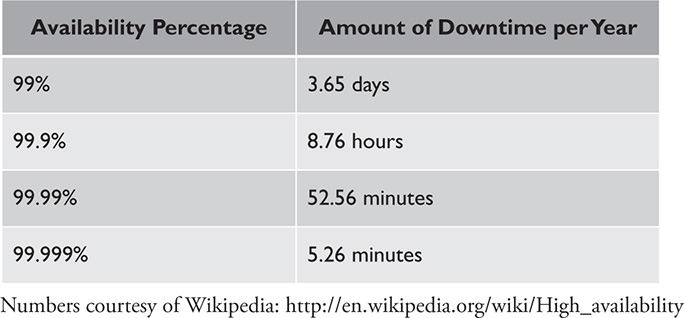

“High availability” is a term often used in relation to networked systems and equipment; it is the measure of the tolerance a business has for downtime with critical systems or processes. If an organization is primarily involved in e-commerce, for example, then a web-based product ordering and processing system should be available 24 hours a day, seven days per week, since online orders can be taken at any time. Of course, high availability applies to critical services; the less critical a service or system is, the less availability it may require. High availability is measured in terms of what systems personnel refer to as “the nines.” It’s expressed as a percentage and decimal points of uptime. For example you might see 99.99 percent availability, or even 99.999 percent availability (referred to as “5 nines” of availability). Obviously, the more decimal places, the higher availability required.

At first glance there may not seem to be much of a difference between 99 percent availability and 99.999 percent availability. When you measure in terms of tolerable downtime, say, on an annual basis (365 days per year), then 99 percent availability is equivalent to an uptime of 361.35 days per year. That means that there will be a total downtime in that year of 3.65 days. For most organizations, especially in this modern Internet age where customers expect to be able to order products and services instantly, at any time during the day or night, that amount of downtime would be unacceptable. Contrast that to five nines of availability, which is 99.999 percent availability, and is equivalent to slightly over 5 minutes of downtime per year (5.26 minutes). From a practical perspective, it’s likely that all of that downtime won’t take place at once during the year, but during an incident or disaster, it could. This leads to discussion on how organizations can maintain a high availability percentage through system and process redundancy, and this is the topic of the next section. Figure 41-2 shows the different levels of high availability, with regards to “the nines.”

Figure 41-2 Levels of high availability expressed as “the nines”

Redundancy

Redundancy is an important factor in maintaining the organization’s ability to continue operations after a disaster. This means the organization must maintain redundant systems, equipment, data, and even personnel. It also may mean the organization maintains redundant facilities, such as alternate processing sites. This last item will be discussed in greater detail in Module 42; for now, the focus is on redundant systems and data. Redundant processes are also important, since critical data or equipment (or even public infrastructure, such as power) may be unavailable, forcing the business to come up with an alternative process for conducting its mission.

Redundancy in systems and data can be achieved several different ways, or usually in a combination of several ways at once. Redundancy is strongly related to the concept of fault tolerance, which is the ability of the system to continue to operate in the event of a failure of one of its components. Redundant systems, as well as the components they comprise, contribute to fault tolerance. Two ways to provide for both redundancy and fault tolerance include clustering and load balancing, terms that are usually associated with servers, data storage, and networking equipment (such as clustered firewalls or proxy servers), but that could be applied to a variety of assets and services. Data redundancy can also be provided by backups, which can be restored in the event of an emergency; this is discussed in Module 42.

Clustering, in the traditional sense, means to have multiple pieces of equipment, such as servers, connected together, which appear to the user and the network as one logical device, providing data and services to the organization. Clusters usually share high-speed networking connections as well as data stores and applications and are configured to provide redundancy in the event that a single member of the cluster fails. The two simplest configurations involve either an active-active or active-passive system. In an active-active configuration, all servers or devices are online, and any one member of the cluster can service a data or application request at any given time (referred to as load-balancing). If any single member device fails, the other member devices in the cluster will service a request, and all will be transparent to the user. In an active-passive configuration, however, only designated members of the cluster are allowed to service requests, and in the event of their failure, another device must be designated as an active member. This configuration isn’t always automatic and could require time and intervention on the part of an administrator.

Exercises and Testing

Even with the most extensive business continuity and disaster recovery plans, something may be missed or not considered by the organization. The best-laid plans can come undone with unexpected events or contingencies. For these reasons, you should exercise and test your plans periodically to make sure they work as well as they should. Plans should be exercised and tested whenever there are significant changes to them or to the business environment, to ensure that the changes were taken into account in the plans. You should also exercise and test them periodically to refresh everyone’s memory on what to do during an incident or disaster, and as part of regularly scheduled training. When we test business continuity and disaster plans, we can often discover things that were forgotten or weren’t adequately considered. In this respect, testing your plans can help you improve them and take into account any possible scenarios that could occur. Now let’s discuss the different types of exercises and tests.

Documentation Reviews

The documentation review is the simplest form of test. In this type of test, the business continuity plan, disaster recovery plan, and associated documents are reviewed by relevant personnel including managers, recovery team members, and anyone else who may have responsibilities directly affecting plans. The plans may be reviewed in a group setting or by simply passing them along from team member to team member, who review them in turn. Plans should be reviewed periodically, such as on an annual or semiannual basis, or at least when there are significant changes to the plan or the operating environment. During these reviews the plans are checked for currentness, effectiveness, resource allocation, and general common sense. These formal reviews should be documented for historical record purposes and as part of compliance with governance (including corporate and legal requirements).

Tabletop Exercises

A tabletop exercise is a type of group review, sometimes literally conducted around the conference room table. In a tabletop exercise, there’s a little bit more involvement by the key players, including managers, team members, and other critical personnel who have business continuity and disaster recovery duties. During the exercise, the group may be presented with scenarios in which they will be directed to respond accordingly. The response can be verbal or written; typically no actual recovery operations are conducted during a tabletop exercise. These types of exercises are useful in that they allow everyone involved to step through the business continuity and recovery processes and may help to point out deficiencies in the plans. They are also useful training tools and serve to help team members become more familiar with and accustomed to their roles within the plan.

Walkthrough Tests

A step above the tabletop exercise is the walkthrough test. In a walkthrough test, there’s usually more involvement by relevant team members, and they may actually go through the motions of fulfilling the responsibilities and conducting the activities required during an actual incident or disaster. This test may be conducted partially in a conference room or out in the actual operations areas of the business. Normally, systems are not actually shut down, and actual recovery operations are not performed. Team members may simulate response activities as much as possible without actually conducting them. A walkthrough test can help point out logistical or practical issues not previously considered around a conference room table, such as the need to move heavy equipment (and maintain the appropriate gear and tools to do so nearby). This type of exercise is also useful as both a training tool and as a way to ensure that the plan works as it should.

Full Tests and Disaster Recovery Exercises

At some point, the organization may conduct a full-scale test of its business continuity and disaster recovery plans. In these types of exercises, all personnel are usually involved and may actually conduct activities as they would during a real incident. Systems may be shut down to simulate their loss, backup data may be recovered to alternate systems, and alternate processing sites may be activated. Parallel processing using both production and backup systems may also be used. This type of exercise is the most involved and will likely take away some significant time from actual production activities. It should not, however, be permitted to impose unnecessary risk on the business by shutting down and recovering actual production systems during the exercise, as this may lead to an actual incident or real downtime. Since this type of test normally requires extensive resources, such as people, equipment, and so on, it is typically conducted infrequently.

Module 41 Questions and Answers

Questions

1. All of the following are considered business continuity activities, except:

A. Evacuating a building during a fire

B. Processing only critical business transactions

C. Manually inventorying parts in a warehouse in the event of a power loss

D. Hand-writing business orders in the event of a systems failure

2. Which of the following is considered one of the first activities performed during the BCP process?

A. Disaster response

B. Business impact analysis

C. Server clustering configuration

D. Critical data backup

3. Which of the following activities is performed as part of the BIA process?

A. Identify redundant equipment

B. Identify emergency evacuation routes

C. Identify roles and key responsibilities

D. Identify critical systems and components

4. Which of the following problems does redundancy normally help to solve?

A. Poorly trained disaster response team members

B. Inadequate bandwidth

C. Single points of failure

D. Data loss

5. Which two potential recovery and continuity issues are solved through succession planning? (Choose two.)

A. Alternate business processes

B. Lack of disaster recovery training

C. Alternate leadership positions

D. Critical disaster team member alternate positions

6. __________ involves both near- and long-term planning for the computing infrastructure, directly affecting system and equipment-related contingencies.

A. Succession planning

B. IT contingency planning

C. Fault-tolerance

D. Clustering

7. You are trying to determine the appropriate level of high availability for a server. The server must be available on a constant basis, and downtime in a given year cannot exceed 10 minutes. Which of the following reflects the level of availability you require?

A. 99.999 percent availability

B. 90 percent availability

C. 99.9 percent availability

D. 99.99 percent availability

8. Which of the following clustering configurations involves a group of servers configured to service a request instantly and automatically if one of the members of the cluster fails?

A. Passive-active

B. Passive-passive

C. Active-passive

D. Active-active

9. All of the following are valid reasons to test and exercise BCP and disaster recovery plans, except:

A. To train and familiarize personnel with the BCP and DR plans

B. To ensure that equipment and supplies are in place, accessible, and functional in the event a real disaster occurs

C. To create an actual incident the response team must recover from, in order to test the team’s effectiveness

D. To discover any issues or problems the planning process did not take into account

10. Which of the following types of BCP tests may occur in the operational areas of the business, and is designed to familiarize the response team with the response steps involved, but usually involves only simulated responses?

A. Walkthrough exercise

B. Full exercise

C. Documentation review

D. Parallel testing

Answers

1. A. Evacuating a building during a fire is part of disaster response and recovery, whereas the other choices can all be conceivably performed as part of keeping business operations going.

2. B. A business impact analysis is one of the first activities performed during the BCP process. The other activities are also important but may be performed at various other times during the process.

3. D. Identifying critical systems and components is part of the BIA process, whereas all of the other choices are performed during other parts of the BCP process.

4. C. Redundancy typically solves issues related to single points of failure. The other issues are normally resolved using other solutions.

5. C, D. Alternate leadership positions and critical disaster team member alternate positions are personnel issues that are resolved through effective succession planning as part of BCP.

6. B. IT contingency planning involves both near- and long-term planning for the computing infrastructure, directly affecting system and equipment-related contingencies.

7. A. 99.999 percent availability is required to maintain a downtime of less than 10 minutes per year. All other choices would result in a downtime greater than 10 minutes per year.

8. D. An active-active cluster configuration will instantly and automatically service a request if one of the members of a server cluster fails.

9. C. Creating a real incident in order to test the effectiveness of the response team may actually interrupt the business operations or seriously impact its ability to function.

10. A. A walkthrough exercise may occur in the operational areas of the business and is designed to familiarize the response team with the response steps involved, but it usually involves only simulated responses.